Abstract

Summary: Selenoproteins contain the 21st amino acid selenocysteine which is encoded by an inframe UGA codon, usually read as a stop. In eukaryotes, its co-translational recoding requires the presence of an RNA stem–loop structure, the SECIS element in the 3 untranslated region of (UTR) selenoprotein mRNAs. Despite little sequence conservation, SECIS elements share the same overall secondary structure. Until recently, the lack of a significantly high number of selenoprotein mRNA sequences hampered the identification of other potential sequence conservation. In this work, the web-based tool SECISaln provides for the first time an extensive structure-based sequence alignment of SECIS elements resulting from the well-defined secondary structure of the SECIS RNA and the increased size of the eukaryotic selenoproteome. We have used SECISaln to improve our knowledge of SECIS secondary structure and to discover novel, conserved nucleotide positions and we believe it will be a useful tool for the selenoprotein and RNA scientific communities.

Availability: SECISaln is freely available as a web-based tool at http://genome.crg.es/software/secisaln/.

Contact: charles.chapple@crg.es

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

Selenoproteins are a diverse family of proteins characterized by the presence of the 21st amino acid, selenocysteine (Sec or U). Selenocysteine is co-translationally inserted into the growing polypeptide chain in response to UGA, otherwise read as a stop codon. The correct recoding of UGA to Sec requires the presence of a stem-loop structure, the SECIS element in the 3 untranslated region (UTR) of selenoprotein gene transcripts. Accordingly, the presence of a suitable SECIS element has been used in many studies as a tool for the computational prediction of novel selenoproteins (Castellano et al., 2001; Kryukov et al., 1999; Lescure et al.; 1999) and a specialized tool for SECIS prediction, SECISearch (Kryukov et al., 2003), has already been described and has been widely used.

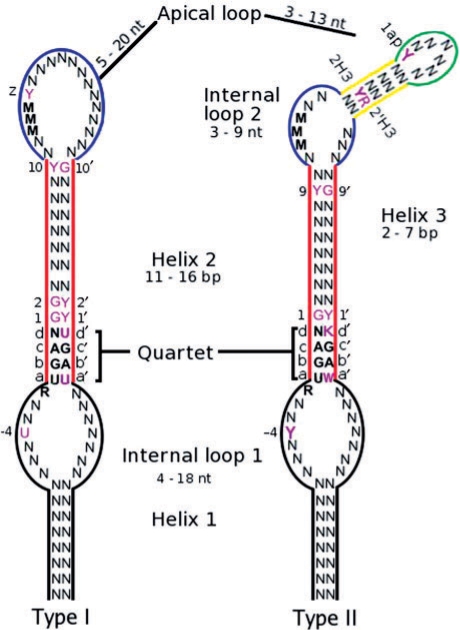

There are two types of eukaryotic SECISes, type I and type II differing at the apex by the presence of the additional helix 3 in type II (Fagegaltier et al., 2000; Grundner-Culemann et al., 1999; Walczak et al., 1996 see Fig. 1. Although the SECIS structure is conserved, there is little sequence conservation beyond the consecutive non-Watson-Crick base pairs UGAN/KGAW constituting the quartet, an unpaired A 5 to UGAN and a run of As in the apical loop/internal loop 2 (Fagegaltier et al., 2000; Walczak et al., 1996). Of these only the UGA/GA of the quartet is invariable1 (e.g. Buettner et al., 1996; Lobanov et al., 2007). Here, we describe SECISaln, a web-based tool that creates structure-based alignments of an extensive dataset of eukaryotic SECIS sequences. Its implementation led us to uncover novel, conserved sequence elements.

Fig. 1.

Eukaryotic SECIS element consensus sequence. Novel conserved residues are shown in magenta. Where a specific nucleotide is shown, it was observed in that position in 50% or more of the aligned sequences. Where a class of nucleotides is shown, that class was observed in that position in 70% or more of the aligned sequences. Y=U or C, K=G or U, N=any nucleotide, W=A or U, R=A or G, M=A or C. Quartet: four consecutive non-Watson–Crick base pairs. Base pairs forming the quartet were called abcd/a′b′c′d′ for the sake of clarity in the text. Position ‘z’ is the first nucleotide after the run of Ms, positions 2H3/2′H3 are the second base pair of Helix 3 and 1ap the first nucleotide of the apical loop. The range of possible lengths for helix 1 is hard to determine because it depends on the local 2D structure of the mRNA 3′UTR.

SECISaln will predict a SECIS element in the query sequence, split it into its constituent parts and align these against a precompiled database of eukaryotic SECIS elements. The user can choose whether the database sequences are sorted by protein family or by species, thereby offering the possibility of comparing the submitted sequence to other, known SECISes. In addition, SECISaln returns a graphical image of the predicted structure of the user-submitted sequence as well as a multiple structural alignment of all SECIS elements of that type already present in the database. SECISaln uses SECISearch for the SECIS prediction step, described in detail in (Kryukov et al. (2003) and is not intended as a replacement for SECISearch. Our patterns and free-energy cutoffs are not stringent and will result in a high false positive rate if used to identify novel SECIS elements. Ideally, SECISaln should be used on sequences which are known to contain a SECIS element, and its main application is the detailed characterization of structural features in the identified SECIS elements, through the multiple structural comparison to other known SECIS elements.

In addition to being the first structural alignment tool for SECIS elements, SECISaln also provides the largest available, manually curated collection of eukaryotic SECISes. Our SECIS collection was built by searching for homologs of all known eukaryotic selenoproteins in NCBIs Refseq mRNA and TIGRs EGO databases. We ran TBLASTN searches using the human (when available, other species when not) selenoproteins as queries. We then extracted the relevant mRNA sequence from the database and identified its SECIS element. We also manually added insect SECIS sequences that had been previously identified (Chapple and Guigó, 2008), but which are not yet present in mRNA databases. This process resulted in a collection of 62 type I and 224 type II SECISes, a clear indication that type II constitute the major part of SECIS elements. Interestingly, although all selenoprotein families had a type II SECIS in at least one species, SelO, SelT, MsrA, DI2, SelS, 15kDa, TR3, SelI, Gpx3 and TR2 had type II SECISes in all species investigated. GPx1 and DI1 had type I SECISes in all species except Danio rerio.

Analyzing the structural alignments produced by SECISaln provided a more detailed picture of SECIS structural features. For instance the length of helix 2, which was previously set to 14 bp, is less constrained and ranges in fact from 11 bp to 16 bp. SECISaln also highlighted previously unknown conserved residues in eukaryotic SECIS elements (see Supplementary Table 1), which can be summarized as a new consensus core sequence for eukaryotic SECIS elements as shown in Figure 1. Most striking of these is an overrepresentation of G at position 1 (3 to abcd) and a corresponding overrepresentation of Y (C or U) at position 1. We also observed a clear overrepresentation of U in type I elements, and Y in type II at position −4. This is particularly surprising since no cross-species sequence conservation has ever been observed five to the quartet, with the exception of the conserved R, and may be connected to the SBP2-SECIS contacts observed in this area (Cléry et al., 2007; Fletcher et al., 2001)

In conclusion, we believe that SECISaln, as has already been demonstrated by the analyses presented here, will be a very useful tool for the analysis and understanding of SECIS elements.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank David Martin for his help with CGI scripting and Marco Mariotti for beta testing the software.

Funding: Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (to R.G.); BioSapiens European Network of Excellence (to R.G.); National Institute for Bioinformatics (www.inab.org) a platform of ‘Genoma Espa na’ (to R.G.); ToxNuc-E program (to A.K.); ACI BCMS of the French Ministry of Research (to A.K.); Pre-doctoral Fellowship from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (to C.E.C.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Footnotes

1 With one exception, the SelT genes of Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora canine have a non-canonical GGA/GA sequence instead (Novoselov et al., 2007).

REFERENCES

- Buettner C, et al. The Caenorhabditis elegans homologue of thioredoxin reductase contains a selenocysteine insertion sequence (secis) element that differs from mammalian secis elements but directs selenocysteine incorporation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:21598–21602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano S, et al. In silico identification of novel selenoproteins in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:697–702. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapple CE, Guigó R. Relaxation of selective constraints causes independent selenoprotein extinction in insect genomes. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cléry A, et al. An improved definition of the rna-binding specificity of secis-binding protein 2, an essential component of the selenocysteine incorporation machinery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:1868–1884. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagegaltier D, et al. Structural analysis of new local features in secis RNA hairpins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2679–2689. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.14.2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JE, et al. The selenocysteine incorporation machinery: interactions between the secis RNA and the secis-binding protein sbp2. RNA. 2001;7:1442–1453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundner-Culemann E, et al. Two distinct secis structures capable of directing selenocysteine incorporation in eukaryotes. RNA. 1999;5:625–635. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299981542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryukov GV, et al. New mammalian selenocysteine-containing proteins identified with an algorithm that searches for selenocysteine insertion sequence elements. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:33888–33897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryukov GV, et al. Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes. Science. 2003;300:1439–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.1083516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescure A, et al. Novel selenoproteins identified in silico and in vivo by using a conserved rna structural motif. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:38147–38154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.38147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobanov AV, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of eukaryotic selenoproteomes: large selenoproteomes may associate with aquatic life and small with terrestrial life. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R198. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoselov SV, et al. A highly efficient form of the selenocysteine insertion sequence element in protozoan parasites and its use in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:7857–7862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610683104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak R, et al. A novel RNA structural motif in the selenocysteine insertion element of eukaryotic selenoprotein mRNAs. RNA. 1996;2:367–379. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.