Abstract

Motivation: Several functional gene annotation databases have been developed in the recent years, and are widely used to infer the biological function of gene sets, by scrutinizing the attributes that appear over- and underrepresented. However, this strategy is not directly applicable to the study of non-coding DNA, as the non-coding sequence span varies greatly among different gene loci in the human genome and longer loci have a higher likelihood of being selected purely by chance. Therefore, conclusions involving the function of non-coding elements that are drawn based on the annotation of neighboring genes are often biased. We assessed the systematic bias in several particular Gene Ontology (GO) categories using the standard hypergeometric test, by randomly sampling non-coding elements from the human genome and inferring their function based on the functional annotation of the closest genes. While no category is expected to occur significantly over- or underrepresented for a random selection of elements, categories such as ‘cell adhesion’, ‘nervous system development’ and ‘transcription factor activities’ appeared to be systematically overrepresented, while others such as ‘olfactory receptor activity’—underrepresented.

Results: Our results suggest that functional inference for non-coding elements using gene annotation databases requires a special correction. We introduce a set of correction coefficients for the probabilities of the GO categories that accounts for the variability in the length of the non-coding DNA across different loci and effectively eliminates the ascertainment bias from the functional characterization of non-coding elements. Our approach can be easily generalized to any other gene annotation database.

Contact: ovcharei@ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics Online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Almost 20 vertebrate genomes have been fully sequenced up to date. Gene annotation of the human, mouse and several other genomes reaches high confidence levels (Pruitt et al., 2007), and functional classification databases provide valuable information to understand the biological processes associated with different groups of genes in these genomes. Gene Ontology (GO) (Ashburner et al., 2000), KEGG (Kanehisa et al., 2006, 2008), OMIM (Boyadjiev and Jabs, 2000; Hamosh et al., 2002, 2005) and OBO Cell Ontology (Smith et al., 2007), are just some of the most widely used functional annotation databases, which have enabled intriguing discoveries during the last decade (Hvidsten et al., 2001; King et al., 2003).

The classical approach to functional inference identifies annotation terms that are significantly over- or underrepresented within a given class of genes; over- or underrepresentations are identified by comparing the count of occurrences for each annotation term to the expected value, which usually arises from considering the number of genes assigned to each category in the complete genome. Several tools have been developed to perform the classification analysis that are mainly based on the hypergeometric test [among them BiNGO (Maere et al., 2005), GO::TermFinder (Boyle EI, 2004) and GOToolBox (Martin, 2004)] or Fisher's exact test, which relies on properties of the hypergeometric distribution [like GOstat (Beissbarth and Speed, 2004) and FatiGO (Al-Shahrour et al., 2004, 2007)].

However, the vast majority of the genome consists of non-protein-coding (non-coding) sequences. Functional non-coding sequences may be associated with protein-coding sequences by either directly or indirectly regulating the expression of protein-coding genes, or playing structural roles in chromosome architecture or encoding RNA genes. In any case, annotation databases for non-coding elements are still in their infancy. In particular, there are at least two databases that store and openly share functional annotation of candidate gene regulatory elements in vertebrates, tested in vivo in mice and zebrafish—Vista Enhancer Database (VED) (Pennacchio et al., 2006) and CONDOR (Woolfe et al., 2007). However, ∼1000 elements profiled in these databases represent only a small fraction of gene regulatory elements in a vertebrate genome, which are expected to exceed the number of exons (∼200 000) (Waterston et al., 2002). In practice, this precludes the application of these databases to the functional annotation of non-coding elements, which could be represented by a set of non-coding SNPs (Schwarz et al., 2008), a set of transcription factor binding sites from ChIP-chip experiments (Hu et al., 2007), or a set of candidate regulatory elements scattered across a vertebrate genome (Ovcharenko et al., 2005; Woolfe et al., 2005), for example. A sensible solution to this problem proposes to infer the function of a given non-coding element from that of the gene it belongs to or the closest neighboring gene; this strategy is especially well justified for promoter or UTR elements. However, the interpretation of the results is not always straightforward—promoter elements only represent a small component of the complex gene regulatory machinery, also constituted by distant intergenic and intronic elements (Machon et al., 2002; Nobrega et al., 2003), which do not necessarily regulate the gene they are inserted in or close to (Lettice et al., 2003; Santagati et al., 2003).

Uncertain association of putative regulatory elements and genes aside, gene annotation databases can be useful to characterize non-coding elements. While the association with the gene is often straightforward for promoters and UTR elements, intronic elements are commonly associated with the gene containing them and intergenic elements are usually associated with the nearest gene. After that, it is reasonable to infer the function of non-coding elements by examining the function of the corresponding set of genes. In a classical approach, the number of genes assigned to a given functional category in this set is compared with the number of genes assigned to that category in the entire genome, and deviations are evaluated according to a statistical test. The problem with this logic is the implicit assumption that the probability of sampling a particular annotation term is equal to the fraction of genes associated with it in the genome, which does not depend on the total number of non-coding elements a particular gene is associated with. Basically, a gene with many non-coding elements and a gene with zero non-coding elements are assumed to have equal probability of discovery through the analysis of their non-coding DNA space, which is obviously wrong and leads to a GO ascertainment bias. As a result, non-coding elements will be predicted in some loci of the genome more often than in others purely by chance, and any random subset of non-coding DNA may appear significantly enriched or depleted for some annotation terms, i.e. the above-mentioned strategy for an indirect functional analysis is biased due to the variable locus length. To correct for the GO ascertainment bias, within the context of functional inference on non-coding elements, the probability of a given annotation term should be set proportional to the fraction of the length of non-coding DNA assigned to it, which is strongly correlated with the length of the locus that contains it, and is highly variable across different loci (Supplementary Fig. 1).

The aim of this work is to evaluate the effect of the variability in locus length on the functional analysis of non-coding DNA. We consider the total population of non-coding DNA elements in the human genome and the annotation terms attributed to their neighbor genes, and assess whether a set of non-coding DNA elements randomly sampled from the genome will appear artificially enriched and/or depleted for any annotation term. In our study, we report systematic false positive associations for a particular set of GO categories; the choice of the GO database is just exemplary. Finally, we propose a statistical method and a set of correction coefficients to perform an unbiased functional analysis for a set of non-coding elements in a genome.

2 METHODS

2.1 GO assignment

We performed the functional classification of non-coding elements based on the GO gene annotation database. Each non-coding DNA element can be associated with a set of GO categories that corresponds to either the gene containing that element or the closest flanking gene, in case of intergenic or promoter elements. Therefore, a locus will consist of a gene together with half of its adjacent intergenic regions; a delimitation closer to the real transcription units would be desirable, but impracticable, while the boundaries proposed here eliminate any ambiguity in the gene assignment of the non-coding elements.

Also, each gene usually has several associated GO categories. Furthermore, the structure of the GO database is hierarchical, so that each GO category is connected to other categories, which may be associated with other genes. The version of the GO database that we employed contained 6592 terms, each assigned to an average of 17 genes. Three quarters of the GO categories are ascribed to at most five genes, while the average gene count for the remaining quarter is 64. Only 18 GO categories are attributed to 1000 or more genes; from these, five describe some molecular ‘binding’, and seven refer to cellular components. We downloaded the RefSeq gene annotation of the human genome (NCBI Build 36.1; hg18) from the UCSC Genome Browser (Karolchik et al., 2003), and identified 17 475 discrete gene loci, with an average locus length of 152 057 bp (the shortest locus was 612 bp, while the longest locus was 4 767 747 bp). The average locus length for a GO category was 159 918 bp, ranging from 1979 bp to 3 204 335 bp; the average locus length of 25% GO categories was longer than 194 230 bp.

2.2 Sampling

For the purpose of this study, we define a non-coding DNA element as a non-repetitive non-coding DNA sequence stretch within a gene locus, much shorter than the complete locus length. This allowed direct sampling of genes from the genome with a probability being a function of the non-coding non-repetitive length of the gene locus.

The population of non-coding DNA elements in the genome is finite, and its probability distribution is discrete. The probability of a given non-coding DNA element is given by its length divided by the total non-coding DNA in the genome (L nc HG=1 359 884 776 nucleotides). We took 1000 random samples for each sample size (n ranging from 100 to 200 000), using the algorithm described in Supplementary Figure 5. We computed the frequency of the GO categories corresponding to each different gene associated with the non-coding elements in each of the 1000 samples.

2.3 GO enrichment/depletion

The usual statistical test for functional enrichment compares the count of GO category associations for a given set of genes to the expected number, which is derived from the count of GO category associations in the complete genome. For each GO category, the test evaluates the probability of observing a number of genes associated with a particular GO category, by comparing it with the total number of genes in the genome that are assigned to that category. This analysis assumes that all genes are equally likely, and the probability of attributing a given function or GO category to a gene only depends on the total number of genes carrying that GO category.

Under such hypotheses, the probability of associating a certain non-coding DNA element to a given GO category can be regarded as

| (1) |

where N GO is the number of genes/loci associated with a given GO category in the set of N HG genes analyzed. Enrichment in a certain GO category can be quantified by computing the probability that the number of non-coding DNA elements in a sample of size n that are associated with a GO category, N GO, is larger than or equal to the observed value m assuming the frequency P GO in all genes. This follows a hypergeometric distribution which approximates the binomial distribution when n/N HG is small n/N HG<20.

For each of the 1000 random samples, we identified the set of different genes associated with non-coding elements, and subsequently counted the frequency of the GO categories associated with these genes. The frequencies of the GO categories were compared with the genomic frequencies. This procedure allows distinguishing enrichments or depletions of specific GO categories in the sample. The probability of obtaining k non-coding DNA elements for a given GO category among a sample of size n by chance, knowing that the reference dataset contains N GO such annotated genes/loci out of N HG=17 475 genes/loci, can be calculated using the hypergeometric distribution. The significance of the enrichment in each of the GO categories was evaluated by summing over the upper tail of the hypergeometric distribution (α=0.05) and applying Bonferroni's multiple test correction. For the later, we multiplied the nominal P-values calculated as described above by the number of tests performed, i.e. the total number of GO categories.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Variable locus length of GO categories

In the present study, we utilized RefSeq gene annotation to define the genomic location of genes and their corresponding loci. First, we utilized all available transcripts to identify 17 475 non-overlapping genes. Next, we split the genome into a set of loci by dividing intergenic intervals in half. We also tested an alternative locus definition, in which the locus boundaries were determined by proximity to the transcription start site, and did not observe an impact on our conclusions (see next section for details).

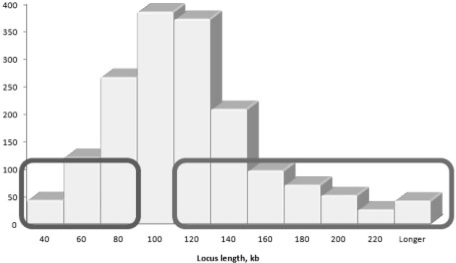

In assessing the variation in the average locus length of different GO categories belonging to the three hierarchies ‘biological process’, ‘molecular process’ and ‘cellular component’, we observed a wide distribution of average locus lengths centered at around 100 kb (Fig. 1). A substantial fraction of GO categories was found to be assigned to genes with either unusually short or unusually long loci. Interestingly, we noted a particular bias towards specific GO categories, and therefore, biological functions, in short and long loci. Concretely, several GO categories related to metabolic processes, as well as some involved in specific responses, are particularly overrepresented in short loci (<80 kb), while GO categories corresponding to development, morphogenesis, regulation and signaling are significantly overrepresented in loci longer than 120 kb (Table 1). Although the substrate of this study is the GO database, other functional annotation databases will most probably present a conceptually similar bias in locus length, as this bias has a biological origin, namely the heterogeneity in the locus length.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of GO categories with respect to the locus length. Left and right tables list the GO categories particularly associated with short and long loci, respectively.

Table 1.

GO categories significantly associated with genes in shorter loci and in longer loci

| Process/function | Locus length (kb) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Genes in shorter loci | ||

| Response | ||

| To unfolded protein | 28.7 | 2.4e-5 |

| To bacterium, defense | 58.5 | 1.3e-5 |

| To biotic stimulus | 58.8 | 1.8e-12 |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | 32.6 | 6.1e-9 |

| Oxidoreductase activity | 38.3 | 1.2e-5 |

| Electron transport | ||

| Mitochondrial | 34.3 | 1.1e-5 |

| ATP synthesis coupled | 36.1 | 1.4e-6 |

| Ribosome | ||

| Structural constituent | 36.8 | 1.7e-8 |

| Biogenesis and assembly | 44.9 | 1.8e-7 |

| Keratinization | 38.2 | 1.2e-6 |

| Epidermal cell differentiation | 43.3 | 1.2e-5 |

| rRNA | ||

| Processing | 50.2 | 9.1e-7 |

| Metabolic process | 51.3 | 8.4e-7 |

| Genes with longer loci | ||

| Morphogenesis | ||

| Embryonic limb | 525.2 | 6.8e-7 |

| Neurite | 185.2 | 1.4e-7 |

| Development | ||

| Limb | 483.1 | 6.0e-8 |

| Lung | 283.2 | 7.3e-6 |

| Respiratory tube | 277.0 | 4.4e-6 |

| Brain | 228.2 | 1.3e-7 |

| Central nervous system | 228.1 | 1.3e-11 |

| Tube | 202.0 | 4.4e-9 |

| Regulation of | ||

| Developmental process, positive | 325.3 | 2.1e-5 |

| Cell differentiation, negative | 316.4 | 2.5e-5 |

| Transcription, positive | 183.4 | 1.8e-6 |

| Axon guidance | 320.5 | 2.5e-5 |

| Signaling | ||

| Cyclic-nucleotide-mediated | 214.7 | 2.7e-6 |

| G-protein | 214.7 | 1.3e-6 |

3.2 Ascertainment bias impact

The effect of the ascertainment bias caused by the locus length non-uniformity in GO categories will vary depending on the number of genes each GO category is assigned to and the number of non-coding elements used in a study. A GO category associated with very few genes is less likely to result in an incorrect prediction than a GO category associated with many genes, simply because a GO category with few genes is less likely to be detected at all. A small set of non-coding elements is also less likely to produce false positive associations, as it is less likely to produce any associations at all.

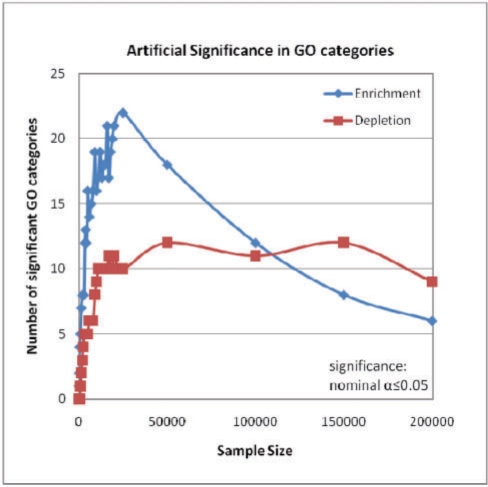

To explore the need of accounting for such ascertainment bias, we randomly selected sets of non-coding elements in the human genome, associated them with their closest genes, and performed a classical GO analysis on the indirectly selected sets of genes. (It should be noted that although this study concentrates on the GO database, the conclusions can be generalized to any other system of functional classification.) We also excluded repetitive elements from the analysis, as functional non-coding elements are expected to be mainly non-repetitive. We will refer to the process of sampling n non-coding DNA elements from the human genome as an experiment. We performed 1000 independent experiments for each sample size n, which ranged from 100 to 200 000, and evaluated enrichment and depletion for different GO categories. We adjusted the significance level by applying the strict Bonferroni's multiple-testing correction (Bonferroni, 1935). Unexpectedly often, aleatory sets of non-coding DNA elements were found to be significantly associated with multiple GO categories (Fig. 2 shows the number of GO categories that appeared to be significant in at least 5% of the experiments for different sample sizes). The number of significantly overrepresented GO categories reached the maximum of 22 for sample size 20 000, and decreased to five as the sample size increased to 200 000. The number of underrepresented categories rapidly plateaued at 10 GO categories in the range of sample sizes plotted. By sampling non-coding elements we indirectly select genes, but the occurrence of each gene is considered only once. For that reason, 20 000 non-coding samples result in ∼43% of the total number of genes in the human genome. When the sample size is large enough so that every gene is effectively represented, the sample coincides with the population. In this case, the number of occurrences for each category meets its expected value. In other words, the number of occurrences of a given GO category converges to the expected value as more genes become represented in the sample, and this accounts for the variation in the number of artificially over- or underrepresented GO categories with the sample size.

Fig. 2.

The average number of GO categories that show up as significantly over- or underrepresented in experiments with random sets of non-coding elements for different sample sizes.

To test whether this effect is a simple consequence of our locus definition, in which intergenic space is split in half, we repeated this experiment using an alternative locus definition, in which a non-coding element is associated with the gene that has the most proximal transcription start site to the element. We found that the alternative locus definition has no impact on the observed effect (Supplementary Fig. 2).

In summary, we found that up to 31 GO categories were significantly over- or underrepresented, depending on the sample size. Specifically, within the usual sample size ranges, over 10 GO categories were overrepresented with a striking confidence level. Considering that each experiment consisted of randomly sampled non-coding DNA elements, and that the experiment was independently repeated a large number of times, this result is not expected. However, the outcome can be easily explained by considering that the non-coding DNA elements do not all have the same probability of being assigned to a gene, but instead have a probability that depends on the locus length.

3.3 Systematically biased GO category assignments

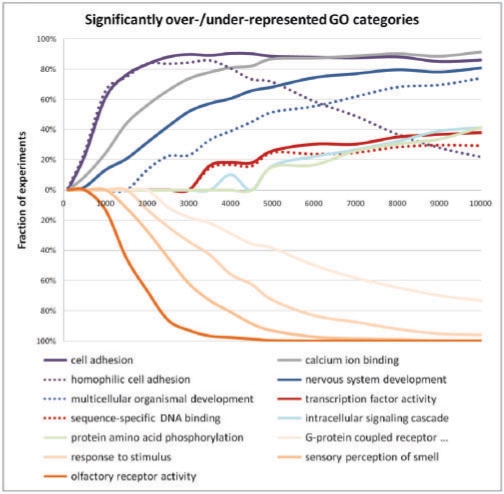

The fact that random sets of non-coding elements appear to be significantly enriched in certain GO categories is alarming. Nevertheless, an even more worrisome question is whether any of such associations between random sets of non-coding elements and GO categories occurs systematically, as this would suggest that some particular GO categories are likely to be reported as significant on a regular basis. For that purpose, for a given sample size n, we analyzed GO categories that were reported as significantly over- or underrepresented in at least 25% of the experiments (Fig. 3). We observed a systematic significant association for a total of 13 GO categories (nine overrepresentations and four underrepresentations). It is interesting to note that the majority of the overrepresented GO categories relate to basic cellular processes (cell adhesion, binding, transcription factors and development), while underrepresented GO categories correspond to lineage-specific and adaptive features (response and receptor categories). Not surprisingly, these constitute a subset of the GO categories for which we observe a large deviation from the uniform distribution in relation to the locus length (Table 2 summarizes the ratio between the average locus length for the loci associated with each particular GO category

represented in Figure 3 and the average locus length in the human genome

represented in Figure 3 and the average locus length in the human genome

.

.

Fig. 3.

Significantly over- and/or underrepresented GO categories (showing only categories which are significant in at least 25% of the experiments). The x-axis represents different sample sizes, only within a range in which the number of GO categories over- and/or underrepresented shows high variation.

Table 2.

Significantly over/underrepresented GO categories (showing only categories which are significant in at least 25% of the experiments)

| GO id | Description |

|

|---|---|---|

| Overrepresentation | ||

| GO:0007156 | Homophilic cell adhesion | 4.7 |

| GO:0007155 | Cell adhesion | 2.3 |

| GO:0007399 | Nervous system development | 1.9 |

| GO:0005509 | Calcium ion binding | 1.7 |

| GO:0007242 | Intracellular signaling cascade | 1.4 |

| GO:0043565 | Sequence-specific DNA binding | 1.4 |

| GO:0007275 | Multicellular organismal development | 1.3 |

| GO:0006468 | Protein amino acid phosphorylation | 1.3 |

| GO:0003700 | Transcription factor activity | 1.2 |

| Underrepresentation | ||

| GO:0007186 | G-protein coupled receptor protein signaling pathway | 0.7 |

| GO:0050896 | Response to stimulus | 0.6 |

| GO:0007608 | Sensory perception of smell | 0.4 |

| GO:0004984 | Olfactory receptor activity | 0.3 |

Overrepresented GO categories appear to have ratios >1, while underrepresented GO categories consist of shorter loci, on average.

For example, the category ‘homophilic cell adhesion’ appeared to be consistently overrepresented in random sets of 500 and more non-coding elements. More precisely, sets of 500 non-coding elements were significantly associated with this category in 25% of independent experiments, while sets of 2500 non-coding elements were significantly associated with this category in more than 85% of experiments. Interestingly, 55 of the 94 genes associated with homophilic cell adhesion are cadherins. Cadherins (Supplementary Table 2) are a superfamily of adhesion molecules with function in cell recognition, tissue morphogenesis and tumor suppression (Angst et al., 2001). Cadherin genes are often flanked either on one or on both sides by a so-called gene desert [an extremely long intergenic region (Ovcharenko et al., 2005)], and this genome architecture is well conserved in mammals and birds (Angst et al., 2001; Wu and Maniatis, 2000; Wu et al., 2001). The characteristic long locus length of these cadherins contributes to the association bias of the homophilic cell adhesion category, which appears as one the top candidates for the systematic false positive annotation of non-coding elements.

In summary, these results indicate that the effect of the locus length heterogeneity and the unevenness of the GO category distribution with regards to it are not negligible and should be appropriately accounted for in functional inference of non-coding elements. The consequence of observing artificially overrepresented categories is conceptually different from that of detecting underrepresented categories. Given a non-coding element, in the former case the results might suggest a function that it does not actually fulfill (false positive), while in the latter case, evidence for a certain function might be simply omitted (false negative).

3.4 Locus length correction

We have shown that the distortion in the distribution of the GO categories in relation to the locus length may lead to erroneous conclusions in the context of the functional annotation of non-coding elements. However, such bias can be excluded by simply introducing probability correction coefficients that depend on the average locus length of each GO category. To account for the heterogeneous locus length in the human genome, we suggest considering the length of the non-coding DNA associated with each GO category, as described below.

If we randomly sample non-coding elements from the human genome, the probability of observing a certain GO category is

| (2) |

where L nc GO is the total length of the non-coding DNA in the loci a given GO category, and L nc HG is the total length of the non-coding DNA in the human genome (Supplementary Fig. 3).

The probability of observing a certain GO category assuming that all genes in the human genome occur randomly with the same frequency is

| (3) |

where N GO is the number of genes/loci associated with a given GO category and N HG genes is the number of genes/loci in the human genome.

Then, we define a correction coefficient CCGO for each GO category (Supplementary Table 1), such that

| (4) |

and

| (5) |

The selection of n GO categories at random from the entire genome can be modeled as a binomial distribution where the success of an event is defined as selecting a certain GO category with a probability that depends on the length of the non-coding DNA in the loci that GO category is associated with.

If we observe m instances of a GO category, we can calculate its P-value under a random model, as 1 minus the cumulative binomial probability of selecting that particular GO category with a frequency m−1, which is calculated as

| (6) |

In order to correct for multiple testing, we must multiply that probability by the number B of hypothesis we test for (Bonferroni's multiple-comparison correction). The expected frequency of a GO category is

We propose to use the ratio of observed to expected frequencies as a rough indicator of enrichment; a ratio above one indicates that the GO category is enriched in the sample with respect to its average expectation, while a ratio below one indicates a depleted GO category. However, it must be noted that this ratio will overestimate GO categories with few expected occurrences.

3.5 Validation

In addition to the aforementioned experiments, we discarded artifacts caused by the sampling method, correlation between GO categories or the threshold chosen for establishing the significance by repeating 1000 sampling experiments from the finite population of non-coding DNA elements at random and testing each GO category for enrichment/depletion using a binomial distribution. As expected, when we computed the P-values using a binomial distribution with parameters n (sample size) and

, where

, where

is the probability of observing the total length of non-coding DNA indirectly assigned to a particular GO, we could not detect any particular GO category significant in 5% or more of the experiments. However, when we repeated the calculations using a binomial distribution with parameters n (sample size) and P

GO, where P

GO is the probability of observing all genes in the genome that are assigned to a particular GO, we obtained a list of over- and underrepresented categories very similar to that produced with the hypergeometric distribution.

is the probability of observing the total length of non-coding DNA indirectly assigned to a particular GO, we could not detect any particular GO category significant in 5% or more of the experiments. However, when we repeated the calculations using a binomial distribution with parameters n (sample size) and P

GO, where P

GO is the probability of observing all genes in the genome that are assigned to a particular GO, we obtained a list of over- and underrepresented categories very similar to that produced with the hypergeometric distribution.

Finally, we would like to mention that the inclusion of repetitive elements in the analysis does not alter the results, as their locus span is strongly correlated with the locus length (data not shown). Also, to confirm that the observed effect is not associated with either repeat-rich or repeat-poor regions we analyzed the relation between the number of non-coding non-repetitive elements in a locus and repeat density. We found that loci with the excessive number of non-coding non-repetitive elements that contribute to an enrichment of artificial GO associations have average repeat density and are not biased towards either repeat-rich or repeat-poor regions (Supplementary Fig. 4).

4 DISCUSSION

GO databases provide a variety of tools for the functional analysis of genes. Due to the current lack of exhaustive databases describing functional non-coding DNA elements, it has become a usual practice to indirectly infer the biological role of selected non-coding elements from the functional analysis of their flanking genes. As we have shown, the high heterogeneity locus length in the human genome and the uneven distribution of the GO categories in relation to the locus length can bias functional inference. Therefore, the P-values for the GO categories that clearly deviate from the assumptions made by the hypergeometric test should be computed considering that the probability of a given GO category does not only depend on the number of genes assigned to it, but also on the length of their loci. Otherwise, categories that are particularly associated with very long or very short loci might appear artificially over- or underrepresented, respectively. As an approximate solution to the problem caused by the variability in the locus length, we propose the use of correction coefficients, which take into consideration the genome span of non-coding DNA corresponding to different GO categories. The coefficients in Supplementary Table 1 can be easily recomputed for other genomes and other annotation databases according to the procedure described in Section 2.

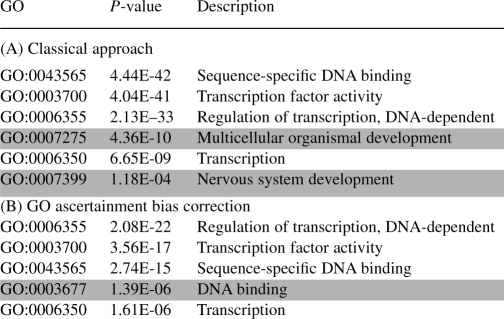

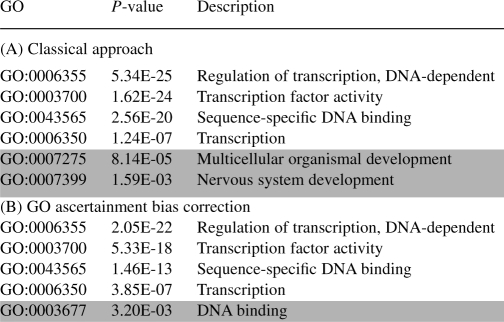

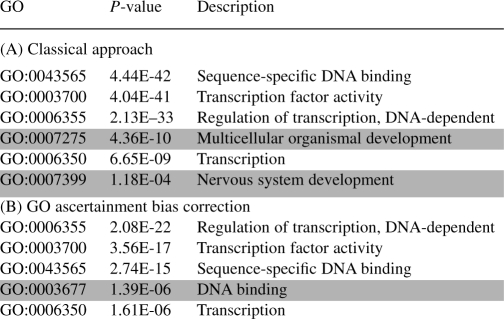

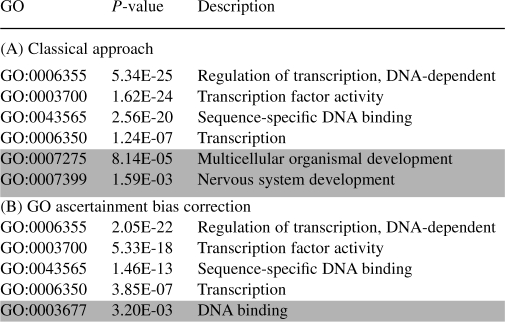

An increasing number of studies report that conserved non-coding sequences tend to cluster in the vicinity of genes implicated in development and transcriptional regulation (termed trans-dev genes) (see for example, Bejerano et al., 2004; Dermitzakis et al., 2005; McEwen et al., 2006; Ovcharenko, 2008; Sandelin et al., 2004; Woolfe et al., 2005). We observe the association of similar GO categories with random sets of non-coding DNA, suggesting that the heterogeneity of the locus length might have had an adverse effect on previous reports. In a reanalysis of studies describing ultraconserved elements (Bejerano et al., 2004) and non-coding elements conserved between human and fish (Ovcharenko et al., 2004; Woolfe et al., 2005), we found that the originally reported association with transcriptional regulation and transcription factors can be strongly confirmed even after the application of the correction for the GO ascertainment bias, while the P-values for associations related to the nervous system and multicellular organismal development fall below the level of statistical significance (Tables 3 and 4). However, it is important to note that our results do not necessarily object the validity of previously published conclusions—if the extreme length of some loci is the result of evolutionary selection and not simply of the locus length variability, the proposed non-coding length correction might artificially reduce the significance of biologically important associations. Obviously, without the availability of extensive annotation databases for non-coding elements, it might be quite difficult to establish a bulletproof approach for using gene annotation databases for an indirect annotation of non-coding elements, but it is also unwise to ignore the potential impact of the locus length on the inference of the function for non-coding elements. Therefore, until we have a large-scale sampling of non-coding functional elements in the human genome that we can use to infer function of other non-coding elements, a practical solution might consist of utilizing the classical GO analysis approach, applying the proposed correction, and analyzing differences and commonalities in the results.

Table 3.

Overrepresented GO categories computed using the usual hypergeometric test (panel A) and accounting for variable locus length (panel B) on the datasets described by Ovcharenko et al. (2004) and Woolfe et al. (2005)

|

Categories removed by the GO ascertainment correction are highlighted, as well as additional categories found after applying the correction.

Table 4.

Overrepresented GO categories computed using the usual hypergeometric test (panel A) and accounting for variable locus length (panel B) on the datasets described by Bejerano et al. (2004)

|

Categories removed by the GO ascertainment correction are highlighted, as well as additional categories found after applying the correction.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Adam Woolfe for his helpful comments on the article, as well as three anonymous reviewers.

Funding: Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health; National Library of Medicine.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Al-Shahrour F. FatiGO: a web tool for finding significant associations of Gene Ontology terms with groups of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:578–580. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shahrour F. FatiGO+: a functional profiling tool for genomic data. Integration of functional annotation, regulatory motifs and interaction data with microarray experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W91–W96. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst BD. The cadherin superfamily: diversity in form and function. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:629–641. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beissbarth T, Speed TP. GOstat: find statistically overrepresented Gene Ontologies within a group of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1464–1465. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejerano G. Ultraconserved elements in the human genome. Science. 2004;304:1321–1325. doi: 10.1126/science.1098119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonferroni CE. Studi in Onore del Professore Salvatore Ortu Carboni. Rome, Italy: 1935. Il Calcolo delle assicurazioni su gruppi di teste; pp. 13–60. [Google Scholar]

- Boyadjiev SA, Jabs EW. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) as a knowledgebase for human developmental disorders. Clin. Genet. 2000;57:253–266. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2000.570403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle EI WS. GO::TermFinder–open source software for accessing Gene Ontology information and finding significantly enriched Gene Ontology terms associated with a list of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3710–3715. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermitzakis ET. Conserved non-genic sequences - an unexpected feature of mammalian genomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005;6:151–157. doi: 10.1038/nrg1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamosh A. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:52–55. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamosh A. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D514–D517. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z. Prediction of synergistic transcription factors by function conservation. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R257. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-12-r257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hvidsten TR. Predicting gene function from gene expressions and ontologies. In: Altman RB, et al., editors. Pacific Symposium in Biocomputing. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co.; 2001. pp. 299–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M. From genomics to chemical genomics: new developments in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:354–357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:480–484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karolchik D. The UCSC Genome Browser Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:51–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King OD. Predicting gene function from patterns of annotation. Genome Res. 2003;13:896–904. doi: 10.1101/gr.440803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lettice LA. A long-range Shh enhancer regulates expression in the developing limb and fin and is associated with preaxial polydactyly. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:1725–1735. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machon O. Forebrain-specific promoter/enhancer D6 derived from the mouse Dach1 gene controls expression in neural stem cells. Neuroscience. 2002;112:951–966. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maere S. BiNGO: a Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3448–3449. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D. GOToolBox: functional investigation of gene datasets based on Gene Ontology. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R101. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-12-r101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen GK. Ancient duplicated conserved noncoding elements in vertebrates: a genomic and functional analysis. Genome Res. 2006;16:451–465. doi: 10.1101/gr.4143406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobrega MA. Scanning human gene deserts for long-range enhancers. Science. 2003;302:413. doi: 10.1126/science.1088328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovcharenko I. Widespread ultraconservation divergence in primates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008;25:1668–1676. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovcharenko I. Interpreting mammalian evolution using Fugu genome comparisons. Genomics. 2004;25:1668–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovcharenko I. Evolution and functional classification of vertebrate gene deserts. Genome Res. 2005;15:137–145. doi: 10.1101/gr.3015505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennacchio LA. In vivo enhancer analysis of human conserved non-coding sequences. Nature. 2006;444:499–502. doi: 10.1038/nature05295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt KD. NCBI reference sequences (RefSeq): a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D61–D65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelin A. Arrays of ultraconserved non-coding regions span the loci of key developmental genes in vertebrate genomes. BMC Genomics. 2004;5:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santagati F. Identification of Cis-regulatory elements in the mouse Pax9/Nkx2-9 genomic region: implication for evolutionary conserved synteny. Genetics. 2003;165:235–242. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz DF. SNPtoGO: characterizing SNPs by enriched GO terms. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:146–148. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. The OBO Foundry: coordinated evolution of ontologies to support biomedical data integration. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:1251–1255. doi: 10.1038/nbt1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterston RH. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature. 2002;420:520–562. doi: 10.1038/nature01262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolfe A. Highly conserved non-coding sequences are associated with vertebrate development. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolfe A. CONDOR: a database resource of developmentally associated conserved non-coding elements. BMC Dev. Biol. 2007;7:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Maniatis T. Large exons encoding multiple ectodomains are a characteristic feature of protocadherin genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:3124–3129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060027397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q. Comparative DNA sequence analysis of mouse and human protocadherin gene clusters. Genome Res. 2001;11:389–404. doi: 10.1101/gr.167301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.