Abstract

Motivation: Automatic classification of high-resolution mass spectrometry proteomic data has increasing potential in the early diagnosis of cancer. We propose a new procedure of biomarker discovery in serum protein profiles based on: (i) discrete wavelet transformation of the spectra; (ii) selection of discriminative wavelet coefficients by a statistical test and (iii) building and evaluating a support vector machine classifier by double cross-validation with attention to the generalizability of the results. In addition to the evaluation results (total recognition rate, sensitivity and specificity), the procedure provides the biomarker patterns, i.e. the parts of spectra which discriminate cancer and control individuals. The evaluation was performed on matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) serum protein profiles of 66 colorectal cancer patients and 50 controls.

Results: Our procedure provided a high recognition rate (97.3%), sensitivity (98.4%) and specificity (95.8%). The extracted biomarker patterns mostly represent the peaks expressing mean differences between the cancer and control spectra. However, we showed that the discriminative power of a peak is not simply expressed by its mean height and cannot be derived by comparison of the mean spectra. The obtained classifiers have high generalization power as measured by the number of support vectors. This prevents overfitting and contributes to the reproducibility of the results, which is required to find biomarkers differentiating cancer patients from healthy individuals.

Availability: The data and scripts used in this study are available at http://www.math.uni-bremen.de/~theodore/MALDIDWT.

Contact: theodore@math.uni-bremen.de

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancies and remains a principal cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality. The early detection of cancer is essential for a successful treatment. Currently, the colonoscopy is used to detect early stage lesions, but this is an invasive and relatively expensive method. Therefore, a different method would be desirable relaying on easily accessible body fluids, like serum. A sensitive blood test might not only detect early stage malignancies, but also premalignant lesions (not part of this study), thereby increasing the chance of survival considerably.

The use of mass spectrometry for searching serum biomarkers in cancer diagnostics was suggested by Petricoin et al. (2002) but was factually flawed. Second-generation studies discovered the importance of avoiding bias and overfitting as well as the need of validation (Ransohoff, 2004). Here a procedure is presented for biomarker extraction from matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) serum protein profiles constructed with attention to generalizability of the achieved results.

Recently, de Noo et al. (2006) demonstrated the feasibility of mass spectrometry based protein profiling for the discrimination of CRC patients from healthy individuals, using quite simple classification methods. This motivated us to develop an advanced procedure of biomarker extraction using the ideas proposed in Schleif et al. (2007): (i) discrete wavelet transformation (DWT) of the spectra, (ii) features (wavelet coefficients) selection by statistical testing and (iii) support vector machine (SVM) classification, see Supplementary Figure 1 for an overall scheme.

Our new procedure presented in this article goes significantly beyond that of Schleif et al. (2007): (i) The actual approach does not only give a classification of spectra, but also supports the location and scoring of spectral features which are putative biomarkers. For this goal, we propose additional wavelet reconstructions to visualize the results; (ii) The classifier assessment is now using a double cross validation scheme to avoid a possible bias of the results; (iii) The feature selection is also included within the double cross validation to avoid potential biases of the performance estimation and (iv) Finally, we investigated the role of the statistical testing and compared different tests and adjustments. In addition to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test we also used a Mann–Whitney (MW) test for feature selection and also applied a Benjamini–Yekutieli (BY) multiple test adjustment to get more confidence about the influence of the feature selection techniques. Finally, we added a detailed analysis of the robustness of the classification as a function of the number of selected features and the number of resulting support vectors. This is helpful to estimate the generalizability of the resulting classification model.

Our procedure was evaluated on new publicly available datasets obtained according to the randomized block design, which helps to minimize impact of potential confounding factors on the experimental side and, thus also to avoid bias.

Being aware of the problem of non-reproducibility of promising results in high-throughput mass spectrometry (Check, 2004; Coombes et al. 2005; Ransohoff, 2004), we assessed the general-ization power of the constructed classifiers as follows.

For different types of the feature selection, the conservativeness was investigated as considering fewer features reduces the risk of overfitting. Moreover, we thoroughly analyzed the generalization error of the classifiers measured as the number of support vectors used for the classification (Bartlett and Shawe-Taylor, 1999).

2 METHODS

2.1 Serum protein profiling

Serum samples were obtained from a total of 66 CRC patients one day before surgery and 50 healthy volunteers (Table 1). All stages of disease were present in the patient group in comparable proportions. The Tumor-Nodes-Metastases (TNM) stages are I-IIIc according to the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (6th edn). Moreover, patients without invasive carcinoma but no premalignant cases were included. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and the Medical Ethical Committee approved the study. Blood was collected in a 10 cc serum separator vacutainer tube and centrifuged 30 min later at 3000 r.p.m. for 10 min. Serum samples were distributed into 0.5 ml aliquots and stored at −70°C until the experiment. The isolation of peptides from serum was performed using the magnetic beads based hydrophobic interaction chromatography (MB-HIC) kit from Bruker Daltonics (Bremen, Germany), according to the manufacturers protocol. α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (0.3 g/l in ethanol:acetone 2:1) was used as matrix. All sample preparation steps were performed on a 8-channel Hamilton STAR pipetting robot (Hamilton, Martinsried, Germany). Using a randomized block design, correcting for demographic and pathological variables, all samples were spotted in quadruple on 3 plates (Table 1). The plates were measured on three consecutive days, Tuesday to Thursday. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry measurements were performed using an Ultraflex TOF/TOF instrument (Bruker Daltonics), equipped with a SCOUT ion source and measured in linear mode. All unprocessed spectra were exported in standard 8-bit ASCII format. They consisted of approximately 65 400 mass-to-charge ratio (m/z)-values, covering a domain of 960–11 170 Da. For more information, see de Noo et al. (2006).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and distribution across plates

| Patients | Controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 64 | 48 | ||||

| Mean age (range) | 67.2 (37–89) | 52.2 (29–78) | ||||

| Male/female ratio | 35/29 | 21/27 | ||||

| Number on plate 1/2/3 | 25/22/17 | 17/16/15 |

2.2 Low-level analysis

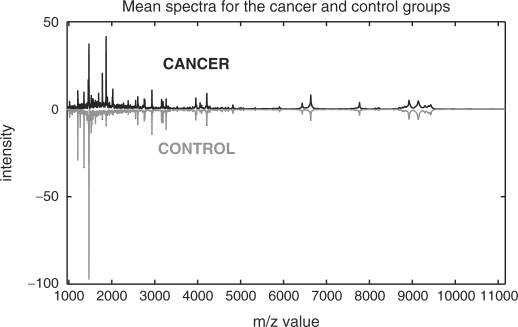

The data have been exported using ClinProTools (CPT) software (version 2.2, Bruker Daltonics) where we performed recalibration, top-hat baseline correction (all with default parameters), outlier detection, and as in the reference paper, data reduction with factor 4. We found two additional outliers in the control group compared with the reference paper, but included one more cancer spectrum in the dataset for classification. The interpolation of all cancer and control spectra on one grid has been done using Matlab. At the end, we had 64 cancer and 48 control spectra of length 16 331 covering a domain of 960–11 163 Da. The mean spectra both for the cancer and control groups are depicted in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Mean spectra for the cancer and control group (inverted, gray spectrum) after low-level processing.

2.3 Discrete Wavelet Transformation

DWT is an important tool in signal processing, in particular for its superior properties of denoising and compression. The central idea of DWT is to find a lossless multi-scale representation of data by means of wavelet coefficients. Informally speaking, each coefficient represents a contribution for some scale and position. A vast literature on DWT is available, covering both theoretical and applied issues, see e.g. Mallat (1999). DWT has been useful for MS data processing for many years, see a review of Leung et al. (1998) for early references.

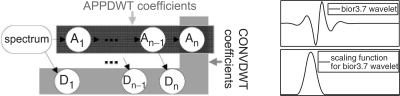

Given a spectrum, the DWT was applied to produce a set of wavelet coefficients which are further used for feature selection and classification. We evaluated two approaches of calculating wavelet coefficients. First, as usual in DWT, we computed detail coefficients of each level together with the approximation coefficients of the maximum level. Second, we considered the approximation coefficients of all levels, instead of the detail coefficients (Figure 2). We denote these approaches CONVDWT and APPDWT, respectively. APPDWT is better suited for biomarker visualization and peak detection since being reconstructed, each approximation coefficient produces the scaling function (a narrow bump) but not the wavelet (an oscillating function) obtained for a detail coefficient (Figure 2). The numbers of calculated detail/approximation DWT coefficients at each level (level number in brackets) are: 8173 (1), 4094 (2), 2054 (3), 1034 (4), 524 (5), 269 (6), 142 (7), 78 (8), 46 (9), 30 (10). This accounts for a total of 16 444 coefficients.

Fig. 2.

Scheme of calculation of APPDWT and CONVDWT coefficients, the bior3.7 wavelet and its scaling function. Ai(Di) denote approximation (detail) coefficients of the i-th level, n is the maximum level (10 in our case). Note that An belongs to both the APPDWT and CONVDWT coefficients.

The bi-orthogonal bior3.7 wavelet was used, because the shape of its scaling function closely matches the peak pattern of MALDI-TOF spectra (Schleif et al., 2007). This is a favorable property of the selected wavelet, since for such a wavelet large values of DWT coefficients can be associated with peaks and a peak is represented by only a few dominant coefficients.

Using wavelet coefficients for classification has the following advantages. First, DWT provides automatic denoising as it separates noise contribution (generating coefficients of the first-scale levels) and signal contribution. Even if we do not carry out the denoising explicitly, this property of DWT helps the statistical feature selection (introduced below) to find significant differences between the two classes. In case of overlapping peaks, the peak picking process becomes complicated and it is usually required to specify a typical a priori peak width. The DWT approach does not require such a specification. However, if there is information available about the m/z range and the expected width of the peaks this can improve the performance significantly.

2.4 Statistical feature selection

In order to find those wavelet coefficients which differentiate between cancer and control spectra, we used non-parametric statistical testing of the null hypothesis Hi that no distinction between cancer and control groups is expressed by the i-th coefficient. Only the coefficients significantly rejecting the hypothesis are used for classification. Note that the applied test of difference is aimed not at extraction of peaks but at extraction of discriminative features. The statistical testing significantly reduces the number of coefficients.

For the statistical feature selection we evaluated the KS and MW tests (significance level 0.05), which are both non-parametric and distribution free tests for assessing whether two samples of observations come from the same distribution or not. Since we compare thousands of coefficients simultaneously, the so-called ‘multiple testing’ adjustment of p-values has to be applied. The aim of the adjustment is to control the type I error rate defined with respect to the multiple testing approach. Among the most popular adjustments are the Bonferroni (Bonf) and the Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) adjustment.

Bonf is perhaps the best known adjustment procedure in multiple testing. It strongly controls the family-wise error rate (FWER) which is the probability of at least one false positive within the set of tests. BH strongly controls the false discovery rate (FDR) for independent test statistics. The FDR is the expected proportion of type I errors among the rejected hypotheses. In addition to the Bonf and BH, we evaluated the BY adjustment which strongly controls the FDR for an arbitrary dependence structure. We considered BY presupposing dependence between DWT coefficients. As discussed, the shape of the chosen wavelet matches a typical peak shape quite well but is still not perfect. Hence, a large peak commonly generates not only one large wavelet coefficient, but several ones positioned close to the peak maximum.

Under the condition of complete null hypotheses (all coefficients do not distinguish cancer and control groups) the FDR would be equivalent to the FWER. Obviously, this is not expected. In this case, the procedures controlling FWER (Bonf) are more conservative than those controlling FDR (BH, BY), because FWER-controlling procedures suppress false positives. FDR-controlling procedures tolerate a few false positives provided that their number is small compared to the number of all rejected hypotheses. For further discussion on multiple testing approaches, see Dudoit et al. (2003).

2.5 SVMs

The selected discriminative DWT coefficients are used as input data for the classification. For the classification, we used a SVM of type C-SVM with a gaussian kernel. SVM is a powerful and popular machine learning technique, widely used for classification and extensively applied in biology (Noble, 2004). The SVM theory and algorithms are described in many papers and books. For a short introduction to SVM from the biological viewpoint, see Noble (2006).

The main idea of SVM is to establish a maximum margin classifier. Linear in its basic formulation, SVM classifiers become non-linear with respect to the given data by exploiting a kernel function or, simply, a kernel. The most often used types of kernels are linear, polynomial and the gaussian kernels. We exploited the gaussian kernel as advised by Schleif et al. (2007) (the linear kernel has also been used, but gave lower recognition rates, results not shown).

The C-SVM classifier we used, has a parameter C, which is a trade-off between maximization of the classifier capacity and minimization of the number of misclassified examples. Together with the width parameter γ of the gaussian kernel they represent the so-called SVM hyperparameters which should be optimized for classification. A variety of implementations of SVM are available; we used the Bioinformatics Toolbox 2.5 of Matlab 7.4 (R2007a).

SVM was selected for classification because of: (i) the small number of hyperparameters and their interpretability, (ii) theoretically substantiated good generalization properties of SVM classifiers, (iii) sparse nature of SVM classifiers, i.e. the classifier is built only on a representative part of the data. The data vectors used (in our case each one contains the wavelet coefficients calculated for a spectrum) are called the support vectors and the other vectors are not taken into account for classification. A disadvantage of SVM is the required runtime to optimize the hyperparameters. For routine classifier generation more efficient alternatives than a simple grid search might be required. The classification of additional spectra is not a performance issue.

2.6 Double cross-validation

For the choice of SVM hyperparameters C and γ we used the double cross-validation (CV) paradigm according to Mertens et al. (2006). Double CV is a bias-reducing scheme of simultaneous parameters estimation and assessment of the classifier. Although double CV dates back to 1974 (Stone, 1974), this approach is still rather new in the field of mass spectrometry. In this field, to our knowledge double CV was first introduced by Mertens et al. (2006) (see this reference for a historical review on double CV) as well as by de Noo et al. (2006) and these references are followed in the essential points.

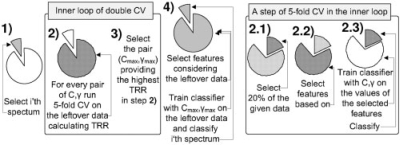

The double CV scheme consists of an outer validation loop and an inner training loop. We used leave-one-out CV for the outer loop and 5-fold CV for the inner loop. In this setting, the i-th step of the double CV scheme consists of two stages: (i) for the i-th element of the data the choice of hyperparameters is done using 5-fold CV on the leftover part (with the feature selection performed within the inner loop), then (ii) the feature selection is done on the leftover part. Finally a classifier is trained with the optimized hyperparameters using all but the i-th spectrum. This classifier is applied for classification of the excluded i-th spectrum. The total recognition rate (TRR, the fraction of correctly classified spectra), sensitivity and specificity are calculated in the outer validation loop. The scheme of the i-th step of the double CV is shown in Figure 3.

Fig. 3.

The i-th step of double CV used for simultaneous parameters estimation and prediction assessment, i goes through all the given spectra.

As usual for SVM, given a train set and a test set, the hyperparameters C and γ are optimized by grid search. The TRR is used as the minimization criterion. At the i-th step of the outer loop, the TRR on all but the i-th spectrum is estimated using 5-fold CV and the hyperparameters minimizing this value are selected. Recall that the final double CV TRR (presented in Table 2) is calculated in the outer loop.

Table 2.

Double CV classification results for the detection of cancer using the proposed procedure

| DWT type | Test | TRR |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

Number of coefficients |

Mean number of SV |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BH | Bonf | BY | BH | Bonf | BY | BH | Bonf | BY | BH | Bonf | BY | BH | Bonf | BY | |||||||

| APPDWT | KS | 96.4 | 96.4 | 96.4 | 96.9 | 98.4 | 98.4 | 95.8 | 93.8 | 93.8 | 6219 | 1545 | 3392 | 55 | 44 | 49 | |||||

| APPDWT | MW | 96.4 | 97.3 | 97.3 | 96.9 | 98.4 | 96.9 | 95.8 | 95.8 | 95.8 | 7068 | 1784 | 3920 | 56 | 43 | 52 | |||||

| CONVDWT | KS | 95.5 | 95.5 | 96.4 | 96.9 | 96.9 | 96.9 | 93.8 | 93.8 | 95.8 | 603 | 299 | 419 | 66 | 54 | 49 | |||||

| CONVDWT | MW | 94.6 | 94.6 | 96.4 | 95.3 | 96.9 | 96.9 | 93.8 | 91.7 | 95.8 | 613 | 303 | 438 | 81 | 61 | 55 | |||||

APPDWT and CONVDWT specify the ways of wavelet coefficients calculation. Column ‘Number of coefficients’ contains the number of discriminative coefficients selected. Column ‘Mean number of SV’ shows mean number of support vectors describing the generalizability of the classifier: a large number indicates overfitting.

Note that a step of the double CV with leave-one-out CV in the outer loop and 5-fold CV in the inner loop simulates clinical diagnosis with 5-fold CV used for training. In double CV, this step is repeated for each spectrum thus providing the TRR and other characteristics of the considered prediction procedure. After method evaluation, having a training dataset and a new patient sample coming in, we (i) optimize C and γ using 5-fold CV on the training data, (ii) select discriminative coefficients of the training dataset, (iii) apply the classifier with the best parameters to the extracted features of the new sample spectrum.

2.7 Biomarkers

Having obtained the classification results, we are interested to interpret the wavelet coefficients used in the classification and to identify putatitive biomarkers. For this purpose, we calculated the parts of the spectra represented by the selected wavelet coefficients. Given the selected wavelet coefficients for each spectrum, we reconstructed the m/z ranges represented by these coefficients. Then we computed the class-discriminating m/z ranges by averaging the resulting spectral components of all spectra within each class. For CONVDWT coefficients, the reconstruction is done using inverse wavelet transformation. Unfortunately, an inverse wavelet transformation is not possible for APPDWT coefficients. Therefore, for each level of the DWT we reconstructed the one-level signal from the selected approximation coefficients. From the produced one-level signals we took the maximum value for each m/z-value.

Moreover, in order to find the most class-discriminative features of the spectra, we studied the parts of the spectra which correspond to a prespecified number of the most significant wavelet coefficients, i.e. the coefficients having the lowest P-values of the statistical test.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Classification results

The results of applying the double CV simultaneous parameters choice and classifier assessment scheme together with the introduced wavelet-based approach are given in Table 2. The achieved TRR, sensitivity and specificity for all tests and adjustments are higher than those reported by de Noo et al. (2006) which are 92.6%, 95.2% and 90.0%, respectively (even taking into account that we excluded one additional outlier). The one cancer sample misclassified by all the classifiers has late TNM stage (IIIc). Using APPDWT gave better recognition rates than CONVDWT and the combination of MW and Bonf (or BY) for APPDWT provided the best results (97.3% TRR). Note that the achieved sensitivity is higher than the specificity as also reported by de Noo et al. (2006). The runtimes (15+9 grid points, 112×(5+1) train-test runs for each grid point) on an Intel 2.66 GHz PC were ∼9 h (KS, Bonf), 17 h (KS, BH/BY), 22 h (MW, Bonf) and 30 h (MW, BH/BY). We also compared our procedure with CPT v.2.2. Since double CV is not included in CPT yet, we used the leave-one-out CV evaluation both in CPT and our procedure. Moreover, the technical replicates have not been averaged (that is not implemented in CPT) resulting in 438 spectra. Other preprocessing steps (Section 2.2) were the same. The calculated TRR values are 98.63% produced by our procedure (APPDWT, MW, Bonf) versus, at best, 98.46% for CPT (SVM, automatic number of peaks, KNN3). This number is only slightly smaller than the one obtained with our procedure and the difference can not be considered to be significant. However, note that the peak picking which depends on all spectra is not included in the leave-one-out CV of CPT. The high-recognition accuracies demonstrate the effectiveness of the classifier in revealing the difference between cancer and control spectra.

3.2 Generalization properties

As shown, our classification procedure provides an improved accuracy for cancer detection, and the TRR is several percent better than those originally reported for the same data by de Noo et al. (2006). However, the most important problem in proteomic profiling today is not to gain several percent advance but to find reproducible biomarkers. As Ransohoff (2004) concluded, it is crucial to assess reproducibility of results in some direct way.

Being aware of this problem, we used double CV with disjoint datasets for optimization and validation. The whole procedure (DWT, feature selection, classification) is evaluated in the inner loop of the double CV. This helps to avoid possible bias in results and to make them reproducible. Furthermore, we investigated the generalizability of the derived classifiers as follows.

First, we compared the conservativeness of the statistical test used, in other words, the fraction of wavelet coefficients which are not rejected by the test. This question is related to the ‘overfitting’ problem, because in general a smaller dimension of the data used for the classification results in a reduced risk of overfitting. Table 2 shows the number of selected coefficients for all the tests and adjustments both for CONVDWT and APPDWT. Despite the same TRR provided, MW with Bonf is better than MW with BY since the former combination selects significantly fewer coefficients.

Investigating the conservativeness of the statistical tests is an opportunity to study the generalization properties of the provided classifiers beyond the set of training spectra. An important characteristic of any SVM classifier is the use of only a part of the given vectorial data, the so-called support vectors. If fewer support vectors are used, the classifier is more likely to give good results for an extended set of samples and it is less likely be overfit (Bartlett and Shawe-Taylor, 1999). Table 2 shows the mean number of support spectra used in the outer loop of the double CV.

For the combination (MW, Bonf) the number of support vectors is 43 on average, whilst the training dataset is of size 111. Therefore the classification procedure is able to represent the information discriminating between cancer and control groups with one third of the training spectra.

Also, the generalizability was estimated in the following empirical way. In the outer loop of a double CV we classified spectra with additional normal distributed noise that simulates classification of new data with models trained on the original data. The noise standard deviation was 0.31 which is twice the real noise estimated in the m/z-interval [1200,2400]. For the achieved classification results see Supplementary Table 1. Bonf-classifiers are more general than others as their TRR is only slightly diminished [96.4% for (MW, Bonf) versus 66.1% and 86.6% for (MW, BH) and (MW, BY), using APPDWT coefficients].

Finally, we investigated the stability of the feature selection procedure using double CV. Therefore, we compared the features extracted at each outer iteration of the double CV (Supplementary Figure 2). Except for tiny variations, the feature extraction is very stable. Moreover, we ran the whole classification procedure with the feature selection performed in advance outside of the double CV. The provided classification results were very similar to those presented in Table 2 which indirectly confirms the stability of the feature selection procedure.

3.3 Biomarkers

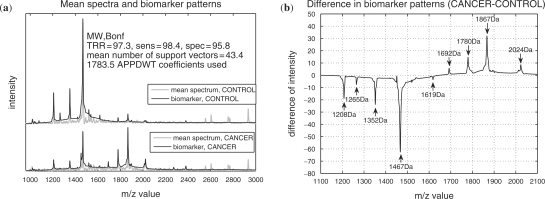

The class-discriminating parts of the cancer and control spectra, computed as described in Section 2.7 for the MW test and the Bonf adjustment using APPDWT coefficients are shown in Figure 4a. Even though the scale of the wavelet coefficients was not specified, the discriminating parts consist of peaks which are all positioned in the m/z-interval 1000–3300 Da (mostly inside 1200–2050 Da).

Fig. 4.

(a) The class-discriminating parts of spectra (MW, Bonf, APPDWT) against the mean spectra (control data are shifted in intensity for better viewing) in the interval 960–3500 Da (no discriminative peaks above 3500 Da). (b) Difference between these parts in the interval 1100–2100 Da. Positive (negative) peaks relate to the cancer (control) spectra.

The fact that discriminative coefficients represent peaks demon-strates the ability of DWT to extract biologically relevant features.

In Figure 4b, the difference between the class-discriminating parts of the spectra (cancer minus control) is presented and the eight peaks with the largest difference are marked: 1208, 1265, 1352, 1467 Da for control spectra and 1692, 1780, 1867, 2024 Da corresponding to cancer spectra, respectively. The difference pattern is very similar to the difference of the mean spectra and to the correlation coefficients presented by de Noo et al. (2006), Figure 3, although our pattern is more detailed. In the results of de Noo et al. (2006), the control peak at 1619 Da (difference in intensity -2.6) is overlooked, the cancer peak at 1692 Da is almost unnoticeable, and the large peak at 2024 Da is not separated from the tiny neighbor peak at 2013 Da.

In the remainder of this section we consider the most discriminative parts of the extracted biomarker patterns. Based on the results of the statistical feature selection, we define the discriminative power (the measure of difference) between cancer and control spectra at some m/z-value through P-values as follows: in DWT several scales are considered (we used 10 scales, the first represents the finest details of the spectra) and for each scale the wavelet coefficients at all possible positions (m/z-values) are calculated. Then for each wavelet coefficient (corresponding to some position and some scale) the statistical difference between its values for the cancer and control data is calculated by means of the statistical test of difference. Thus, the discrimination power at some position and on some scale is expressed by a P-value. As usual, the smaller the P-value, the more discriminative is the position on this scale.

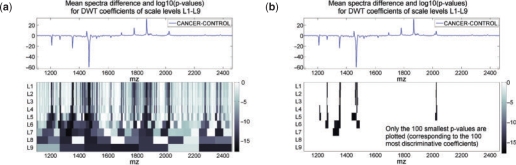

Figure 5a depicts the mean spectra difference and the P-values (using a log10-scale) calculated for the APPDWT coefficients (MW, Bonf) in the interval 1100–2460 Da. In this diagram, each cell corresponds to a P-value and the width of the cell depends on the scale. The cells are colored according to their P-values (log10-scale). Darker cells indicate more discriminative wavelet coefficients. One can clearly see the correspondence between the large peaks expressing the mean spectra difference and the p<10−10 (dark cells in Figure 5a), especially on the first levels where wavelets provide sufficiently fine resolution. This illustrates that our statistical feature selection does not miss the large mean difference between the cancer and control data. Moreover, these results correlate with the biomarker patterns presented in Figure 4b which mostly represent these peaks.

Fig. 5.

The P-values (MW, Bonf) for APPDWT coefficients plotted in log10-scale against the difference of the mean spectra for the wavelet scales L1–L9. (a) All P-values. (b) Only the 100 smallest P-values showing the most discriminative parts of the biomarker patterns.

Thus, the P-values of the wavelet coefficients give an estimate of the discriminative power of features at different scales and positions.

Considering the most discriminative parts of the biomarker patterns (Figure 5b depicts only the 100 smallest P-values), the discriminative power of the peak is not simply expressed by its height. For example, the high intensity difference of the peak at 1867 Da is not found among the most discriminative features obtained. To provide more information for this observation, we did a further evaluation. For different numbers of the coefficients with the smallest P-values we plotted the diagram as in Figure 5b and checked whether the dark cells (discriminative coefficients) correspond to the peaks of largest intensity difference. This compares step-by-step the discriminative power of these peaks. Table 3 shows whether the considered peaks are present in the most discriminative parts of the biomarkers corresponding to different quantities of the smallest P-values or not. It turns out that the most discriminative (the most significant one, significance order 1) peak is at 1265 Da.

Table 3.

Indication of whether the peaks (denoted by their m/z-values, in Da) are reconstructed by the most significant APPDWT coefficients

| P-values | 1208 | 1265 | 1352 | 1467 | 1692 | 1780 | 1867 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ✓ | |||||||

| 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 20 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 50 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 150 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 300 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Significance order | 5 | 1 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 8 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 4 |

| CPT significance order | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 15 |

The MW test is used. The sign ‘✓’ indicates the presence of the peak in the corresponding features. This table shows in particular that the largest peaks are not the most statistically significant (discriminative) ones. The significance order summarizes the table. The ‘CPT significance order’ is calculated by the CPT software.

We compared these results also with the most significant peaks produced by CPT 2.2 which uses a t-test based on the peaks areas, see Table 3, row ‘CPT signifance order’ (for more CPT results see Supplementary Table 2). CPT finds a similar set of peaks (the group of the first three peaks is the same) though there are variations in their order. Unfortunately, TRR cannot be compared as CPT 2.2 does not implement double CV.

Finally the TRR and the generalization properties of classifiers which use only a limited number of the most discriminative wavelet coefficients (Table 4) have been analyzed. As before, the generalizability of a SVM-classifier is estimated by the number of support vectors. It may be unexpected to discover that the TRR provided by a very small number and by thousands of coefficients are comparable. Nevertheless, the classifiers constructed using only a few coefficients need many support vectors. As an extreme example, the most discriminative coefficient on its own provides a recognition rate of 95.5%, but the classifier built on it is not general at all, as 88 spectra (almost 4/5 of the dataset) are used as (in this case one dimensional) SVM support vectors. The large number of support vectors used (compared with 43 for Bonf) most probably indicates overfitting.

Table 4.

Generalization properties of the most discriminative APPDWT coefficients considering the number of support vectors

| Number of coefficients | TRR | Mean number of SV |

|---|---|---|

| 1784 (Bonf) | 97.3 | 43.4 |

| 100 | 95.5 | 39.5 |

| 50 | 94.6 | 49.5 |

| 20 | 94.6 | 62.8 |

| 10 | 95.5 | 66.8 |

| 5 | 95.5 | 70.0 |

| 1 | 95.5 | 88.2 |

The MW test is used to calculate the P-values and to rank the coefficients. For abbreviations, see Table 2.

3.4 Possible modifications

The whole model building and validation procedure needs much computation time. This is mainly due to the two-level grid search and leave-one-out cross validation used in the outer loop. Time could be saved by preselecting the m/z-intervals based on the mean spectra difference, e.g. by taking only coefficients from the intervals with an absolute difference larger than a fraction M (0<M<1) of the maximum absolute difference value. For M=0.05 the intervals constitute 1.6% of all m/z-values but include all the most significant peaks presented in Table 3.

Another way to reduce computation time is to use only selected levels of the DWT. In our dataset the typical peak width is ∼30 Da (empirically estimated). On the 5-th DWT level the width of scaling function is ∼32 Da (15 and 65 Da for 4-th and 6-th levels). Thus the scaling function of the 5-th level is a good approximation for peak. This was confirmed by tests (Supplementary Table 3). Among the test runs with individual levels the best results were obtained for level 5 with the KS test and Bonf adjustment (97.32% TRR and a mean of 43 support vectors).

4 CONCLUSIONS

We evaluated an automatic procedure of CRC detection using MALDI-TOF spectra based on: (i) discrete wavelet transformation; (ii) selection of discriminative wavelet coefficients using the non-parametric difference tests with multiplicity adjustment; (iii) SVM classification. Our procedure is based on the ideas published in Schleif et al. (2007), but was significantly extended as it was summarized in the introduction.

Especially, we evaluated the feature selection here together with the classification using an up-to-date double CV scheme to reduce potential bias. Moreover, we proposed a visualization of the biomarker patterns used for classification.

The presented procedure has been applied to a collection of MALDI-TOF serum protein profiles from 66 CRC patients and 50 controls (de Noo et al., 2006). Compared with (de Noo et al., 2006), a higher TRR, sensitivity and specificity for the detection of cancer are achieved. Examining the properties of SVM classifiers with a different number of wavelet coefficients reveals that the number of required support vectors goes up significantly if too few coefficients are used. Even if such a small subset gives good classification results it indicates an overfitting to the given spectra and might indicate a lack of generalizability of the model considering experimental variability.

The biomarker patterns provided are similar to those of de Noo et al. (2006) but have a higher resolution that in principle allows to find minor discriminating peaks close to other neighboring peaks. The investigation of the found peaks showed that those of them which intensity-wise differ the most between cancer and control spectra are not the most discriminative ones in terms of the statistical feature selection procedure.

We expect that applying our DWT-based classification approach with attention to generalization properties of classifiers, helps to obtain high recognition rates for the detection of cancer and to find biologically valuable and interpretable biomarkers. The molecular identification of the peaks and multi-laboratory validation of the experimental methods and the classification model is beyond the scope of this article. Based on the m/z-values of linear TOF spectra an identification is not possible and further biochemical and MS/MS experiments are required.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Martijn van der Werff for contribution to an initial variant of the article, Marc Gerhard for help with ClinProTools software and Jens Fuchser for proofreading of the article.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Bartlett P, Shawe-Taylor J. Generalization performance of support vector machines and other pattern classifiers. In: Schölkopf B, editor. Advances in kernel methods: SV learning. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 1999. pp. 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Check E. Proteomics and cancer: Running before we can walk? Nature. 2004;429:496–497. doi: 10.1038/429496a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes KR, et al. Serum proteomics profiling – a young technology begins to mature. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:291–292. doi: 10.1038/nbt0305-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Noo M, et al. Detection of colorectal cancer using MALDI-TOF serum protein profiling. Eur. J. Cancer. 2006;42:1068–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudoit S, et al. Multiple hypothesis testing in microarray experiments. Stat. Sci. 2003;18:71–103. [Google Scholar]

- Leung AK, et al. A review on applications of wavelet transform techniques in chemical analysis: 1989–1997. Chemometr. Intell. Lab. 1998;43:165–184. [Google Scholar]

- Mallat S. A wavelet tour of signal processing. San Diego, CA, USA: Acad. Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens BJ, et al. Mass spectrometry proteomic diagnosis: enacting the double cross-validatory paradigm. J. Comput. Biol. 2006;13:1591–1605. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2006.13.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble WS. Support vector machine applications in computational biology. In: Schölkopf B, et al., editors. Kernel Methods in Computational Biology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2004. pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Noble WS. What is a support vector machine? Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1565–1567. doi: 10.1038/nbt1206-1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petricoin EF, et al. Use of proteomic patterns in serum to identify ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2002;359:572–527. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07746-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff DF. Rules of evidence for cancer molecular-marker discovery and validation. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:309–314. doi: 10.1038/nrc1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleif F-M, et al. Comput. Visual. Sci. 2007. Support vector classification of proteomic profile spectra based on feature extraction with the bi-orthogonal discrete wavelet transform. [Epub ahead of print, doi:10.1007/s00791-008-0087-z, March 7, 2008] [Google Scholar]

- Stone M. Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B Met. 1974;36:111–147. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.