Abstract

The routine use of echocardiography has led to an increase in the diagnosis of cardiac papillary fibroelastomas. From 1990 to 2004, 10 cases of papillary fibroelastoma were observed, nine of which underwent successful surgical excision with valve repair or replacement and without major complications. One patient presented with an asynchronous lesion requiring repeat excision. Surgical excision of papillary fibroelastomas is safe and curative, and carries minimal morbidity. A review of the current literature suggests that symptomatic cardiac papillary fibroelastomas should be surgically removed, whereas asymptomatic lesions that are left-sided, large (larger than 1 cm) or mobile should be considered for surgical excision.

Keywords: Heart valve, Surgery, Tumour

Abstract

L’utilisation d’office de l’échocardiographie a donné lieu à une augmentation des diagnostics de fibroélastomes papillaires cardiaques. Entre 1990 et 2004, dix cas de fibroélastome papillaire ont été observés, dont neuf ont été traités avec succès par excision chirurgicale avec plastie ou prothèse valvulaire, sans complications majeures. Un patient a présenté une lésion asynchrone nécessitant une reprise de l’excision. L’excision chirurgicale des fibroélastomes papillaires se révèle sécuritaire et curative, tout en comportant une morbidité minime. Selon une revue de la littérature récente, les fibroélastomes papillaires cardiaques symptomatiques sont justiciables d’une ablation chirurgicale, tandis qu’on peut envisager une excision chirurgicale en présence de lésions asymptomatiques, si elles sont localisées au cœur gauche, volumineuses (de plus de 1 cm) ou mobiles.

Antemortem recognition of cardiac papillary fibroelastomas (CPFs) has increased with the frequent use of echocardiography. Although benign, these tumours can have significant consequences with systemic, cerebral or coronary embolization. We present our experience with CPF, review the epidemiology, clinical presentation and pathology, and highlight important surgical management issues for CPF patients.

METHODS

A search of the cardiac surgery and pathology databases at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute (Ottawa, Ontario) from 1990 to 2004 revealed 10 pathologically confirmed CPFs in nine patients. Charts and operative, echocardiographic and pathology reports were reviewed.

RESULTS

The mean patient age was 54 years, and 67% were men (Table 1). Presentations varied from incidental detection at autopsy to unstable angina, myocardial infarction or cerebral embolization. Eight of nine patients underwent surgery. In four patients, the mitral valve tumour was successfully excised, with concomitant valve repair in three patients and valve replacement in one patient. Of four aortic valve CPF patients, two underwent aortic valve replacement, another underwent exploration with a valve-sparing excision of the tumour, and the fourth patient underwent an attempted valve-sparing excision, but subsequently underwent aortic valve replacement due to moderate aortic insufficiency on postbypass intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). One previously reported patient (1) had a second occurrence and excision of a CPF on the mitral valve after previous excision of a CPF on the tricuspid valve. One excised aortic valve CPF was an incidental intraoperative TEE finding at coronary and mitral valve surgery. There were no mortalities or major postoperative complications.

TABLE 1.

Preoperative and intraoperative data

| Patient | Age (years) | Sex | Tumour location | Size (cm) | Clinical presentation | Surgical procedure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 38 | Male | Tricuspid valve | 1.5×2.0 | Dyspnea | Tricuspid valve repair |

| 1 | 47 | Male | Mitral valve | Multiple; 0.1–0.5 | Transient ischemic attack | Mitral valve repair, excision of mass |

| 2 | 75 | Female | Aortic valve | 1.8×1.2×0.8 | Unstable angina | Aortic valve replacement, repeat CABG |

| 3 | 45 | Male | Mitral valve | 1.4×1.2×1.0 | Incidental echocardiographic finding | Mitral valve repair |

| 4 | 29 | Male | Mitral valve | 2.2×2.0×0.7 | Transient ischemic attack | Mitral valve repair |

| 5 | 31 | Male | Mitral valve | 2.1×2.7×0.5 | Stroke | Mitral valve replacement |

| 6 | 74 | Male | Aortic valve | 0.7×0.6×0.2 | Transient ischemic attack and systemic emboli | Aortic valve replacement, CABG |

| 7 | 65 | Female | Aortic valve | 1.3×0.6×0.5 | Stroke | Aortic valve replacement |

| 8 | 67 | Female | Aortic valve | 1.0×0.3×0.4 | Incidental echocardiographic finding | CABG, mitral valve repair, aortic valve tumour excision |

| 9 | 70 | Male | Aortic valve | Multiple; 0.4–0.5×0.1 | Incidental autopsy finding | Not applicable |

CABG Coronary artery bypass graft

DISCUSSION

Primary cardiac tumours are rare, with an estimated autopsy incidence of 0.02%. CPF is the second most common benign tumour of the heart, commonly occurring on the heart valves. A recent systematic review by Gowda et al (2) of all reported cases of CPF has offered insight into epidemiology, clinical presentation and diagnosis. CPF can occur in any age group, with the majority occurring in adults, and the highest prevalence in the eighth decade. They occur most frequently on valvular surfaces (73%), particularly on aortic (44%) and mitral (35%) valves.

The majority of patients are asymptomatic. Common presenting symptoms include stroke or transient ischemic attack, followed by angina, myocardial infarction, sudden death, heart failure and embolism. TEE is the recommended modality for diagnosis, with an overall sensitivity of 77% (3). Large tumour size, left-sided location and particularly increased tumour mobility are the echocardiographic features associated with embolism.

CPFs consist of multiple fibroelastic papillae originating from a stalk. Histologically, these avascular papillary fronds consist of collagen, proteoglycans and elastic fibres (4). Their resemblance to Lambl’s excrescences has led to the suggestion of a common pathoetiology, perhaps from trauma or an organized thrombus. Other suggested etiologies include congenital origin or complications from valve degeneration, cytomegalovirus or cardiac surgery (5).

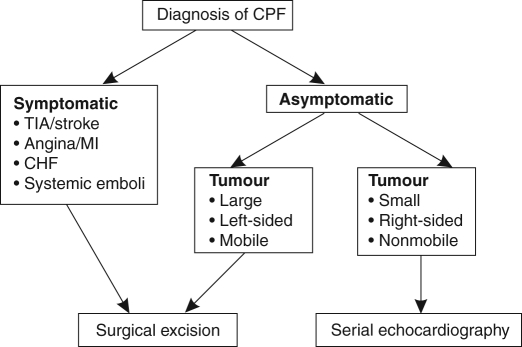

There is general consensus that symptomatic CPFs should be surgically resected; the treatment of asymptomatic patients is less clear. Large, left-sided mobile tumours should be excised to prevent sudden death and emboli. Small, nonmobile tumours may be followed with serial echocardiography and removed if they increase in size, or become mobile or symptomatic (Figure 1). Preoperative TEE is crucial to assess the location and number of lesions, because multiple lesions have been reported.

Figure 1).

Algorithm for the surgical management of cardiac papillary fibroelastomas (CPFs). CHF Congestive heart failure; MI Myocardial infarction; TIA Transient ischemic attack

The surgical incision for valvular CPFs is similar to that used in valve replacement surgery. Left ventricular lesions can be approached through a ventriculotomy, but may be accessible with the help of a cardioscope. CPFs are usually pedunculated and may easily be removed with associated endocardial tissue. Care should be taken to avoid fragmentation to prevent embolization. Resulting valve defects can be closed primarily or with autologous pericardium. Valve repair is preferred and is successful in the majority of cases (approximately 90%). Intraoperative TEE is essential to assess valvular function after tumour excision.

Surgical resection is curative, safe and well tolerated. Although multiple asynchronous occurrences are known to occur, they are extremely rare and serial postoperative echocardiography is not indicated. Patients who are not surgical candidates may be treated with systemic anticoagulation or antiplatelet agents to reduce thrombus formation, although there is no clear evidence to support this.

CPFs are rare, but are increasingly being detected. Recent reviews have highlighted important aspects of the clinical presentation and treatment of CPFs. Surgical excision of this tumour is safe and curative. The availability of echocardiography for the serial evaluation of CPF can lead to a less aggressive approach in asymptomatic patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hynes MS, Veinot JP, Chan KL. Occurrence of a second primary papillary fibroelastoma. Can J Cardiol. 2002;18:753–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gowda RM, Khan IA, Nair CK, Mehta NJ, Vasavada BC, Sacchi TJ. Cardiac papillary fibroelastoma: A comprehensive analysis of 725 cases. Am Heart J. 2003;146:404–10. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun JP, Asher CR, Yang XS, et al. Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of papillary fibroelastomas: A retrospective and prospective study in 162 patients. Circulation. 2001;103:2687–93. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.22.2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boone SA, Campagna M, Walley VM. Lambl’s excrescences and papillary fibroelastomas: Are they different? Can J Cardiol. 1992;8:372–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurup AN, Tazelaar HD, Edwards WD, et al. Iatrogenic cardiac papillary fibroelastoma: A study of 12 cases (1990 to 2000) Hum Pathol. 2002;33:1165–9. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.130105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]