Abstract

Background

Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 is a plant-associated bacterium that inhabits the rhizosphere of a wide variety of plant species and and produces secondary metabolites suppressive of fungal and oomycete plant pathogens. The Pf-5 genome is rich in features consistent with its commensal lifestyle, and its sequence has revealed attributes associated with the strain's ability to compete and survive in the dynamic and microbiologically complex rhizosphere habitat. In this study, we analyzed mobile genetic elements of the Pf-5 genome in an effort to identify determinants that might contribute to Pf-5's ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions and/or colonize new ecological niches.

Results

Sequence analyses revealed that the genome of Pf-5 is devoid of transposons and IS elements and that mobile genetic elements (MGEs) are represented by prophages and genomic islands that collectively span over 260 kb. The prophages include an F-pyocin-like prophage 01, a chimeric prophage 03, a lambdoid prophage 06, and decaying prophages 02, 04 and 05 with reduced size and/or complexity. The genomic islands are represented by a 115-kb integrative conjugative element (ICE) PFGI-1, which shares plasmid replication, recombination, and conjugative transfer genes with those from ICEs found in other Pseudomonas spp., and PFGI-2, which resembles a portion of pathogenicity islands in the genomes of the plant pathogens Pseudomonas syringae and P. viridiflava. Almost all of the MGEs in the Pf-5 genome are associated with phage-like integrase genes and are integrated into tRNA genes.

Conclusion

Comparative analyses reveal that MGEs found in Pf-5 are subject to extensive recombination and have evolved in part via exchange of genetic material with other Pseudomonas spp. having commensal or pathogenic relationships with plants and animals. Although prophages and genomic islands from Pf-5 exhibit similarity to MGEs found in other Pseudomonas spp., they also carry a number of putative niche-specific genes that could affect the survival of P. fluorescens Pf-5 in natural habitats. Most notable are a ~35-kb segment of "cargo" genes in genomic island PFGI-1 and bacteriocin genes associated with prophages 1 and 4.

Background

Recent analyses of bacterial genomes have revealed that these structures are comprised of a mixture of relatively stable core regions and lineage-specific variable regions (also called genomic islands (GIs)), which commonly contain genes acquired via horizontal gene transfer. In bacteria, horizontal gene transfer occurs via conjugation, DNA uptake, transduction and lysogenic conversion, and is mediated largely by mobile genetic elements (MGEs). MGEs are present in most sequenced genomes and can account for the bulk of strain-to-strain genetic variability in certain species [1]. MGEs are part of a so-called "flexible gene pool" and shape bacterial genomes by disrupting host genes, introducing novel genes and triggering various rearrangements. One class of MGEs is derived from bacteriophages and a second is derived from plasmids. Both classes may be associated with integrase genes, insertion sequence (IS) elements and transposons, thus forming elements that are mosaic in nature [2]. Our current knowledge of the impact of MGEs on their hosts comes primarily from pathogenicity islands in which bacteriophages, plasmids and transposons act as carriers of genes encoding toxins, effector proteins, cell wall modification enzymes, fitness factors, and antibiotic and heavy metal resistance determinants in pathogenic bacteria. Much less is known about the diversity and role of MGEs in nonpathogens, in which these elements may enable their hosts to adapt to changing environmental conditions or colonize new ecological niches.

The present study presents the results of an in-depth structural analysis of the MGEs in the genome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5, which is the largest Pseudomonas genome sequenced to date http://www.pseudomonas.com[3]. Strain Pf-5 is a model biological control agent that inhabits the rhizosphere of plants and suppresses diseases caused by a wide variety of soilborne pathogens [3-15]. The original analysis of the Pf-5 genome [3] focused primarily on the strain's metabolic capacity and on the pathways involved in the production of secondary metabolites. The latter encompass nearly six percent of the genome and include antibiotics that are toxic to plant pathogenic fungi and Oomycetes and contribute to Pf-5's broad-spectrum biocontrol activity. The aim of the present study was to more thoroughly analyze and annotate sections of the Pf-5 genome that contain MGEs. Here, we describe one transposase, six regions containing prophages (termed Prophage 01 to 06) and two genomic islands that are present in the Pf-5 genome.

Results and discussion

The genome of P. fluorescens Pf-5 contains six prophage regions that vary in G+C content from 62.6% to 46.8% and two putative genomic islands (Table 1). Three of the prophages exceed 15 kb in length and contain genes for transcriptional regulators, DNA metabolism enzymes, structural bacteriophage proteins and lytic enzymes.

Table 1.

Phage-related elements and genomic islands of P. fluorescens Pf-5 genome

| Feature | Gene range | 5' end | 3' end | Size (bp) |

%GC | Presence of integrase | Type of feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prophage 01 | PFL_1210 to PFL_1229 | 1386082 | 1402957 | 16875 | 62.6 | No | SfV-like prophage |

| Prophage 02 | PFL_1842 to PFL_1846 | 2042157 | 2050549 | 8392 | 46.8 | Yes* | Defective prophage in tRNASer |

| Prophage 03 | PFL_1976 to PFL_2019 | 2207060 | 2240619 | 33559 | 61.2 | Yes | P2-like prophage |

| Prophage 04 | PFL_2119 to PFL_2127 | 2338296 | 2351794 | 13498 | 56.3 | Yes | Defective prophage in tRNAPro |

| Prophage 05 | PFL_3464 to PFL_3456 | 3979487 | 3982086 | 2599 | 55.3 | Yes* | Defective prophage in tRNACys |

| Prophage 06 | PFL_3739 to PFL_3780 | 4338335 | 4395005 | 56670 | 57.3 | Yes | Lambdoid prophage in tRNASer |

| Genomic island 1 (PFGI-1) |

PFL_4658 to PFL_4753 | 5378468 | 5493586 | 115118 | 56.4 | Yes | Putative mobile island PFGI-1 in tRNALys |

| Genomic island 2 (PFGI-2) |

PFL_4977 to PFL_4984 | 5728474 | 5745256 | 16782 | 51.5 | Yes | Genomic island in tRNALeu |

*, the predicted integrase gene contains frameshift mutation(s).

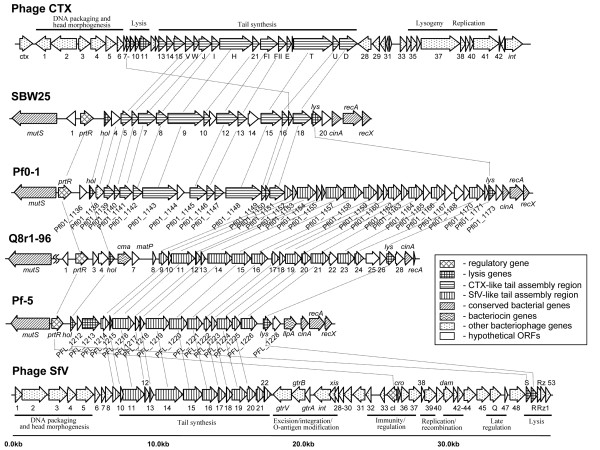

Prophage 01 of Pf-5 and homologous prophages in closely related strains

Prophage 01 spans 16,875 bp and consists of genes encoding a myovirus-like tail, holin and lysozyme lytic genes, a putative chitinase gene (PFL_1213), and genes for a repressor protein (PFL_1210) and a leptin binding protein-like bacteriocin, LlpA1 (PFL_1229) (Fig. 1, see Additional file 1). The tail assembly gene cluster encodes tail sheath (PFL_1216), DNA circulation (PFL_1216), baseplate assembly (PFL_1222), and tail fiber (PFL_1226) proteins that closely resemble their counterparts from the long contractile tail of the serotype-converting bacteriophage SfV of Shigella flexneri [16].

Figure 1.

Organization of prophage 01 from P. fluorescens Pf-5 [49], related prophages in the mutS-recA region of the genomes of other P. fluorescens strains, and bacteriophages CTX [81]and SfV [16]. Predicted open reading frames and their orientation are shown by arrows shaded according to their functional category. Homologous ORFs are connected with lines.

We (D.V.M. and L.S.T.) previously identified a highly similar prophage element during a study focused on genetic traits contributing to colonization of the plant rhizosphere by P. fluorescens. In that project [17], we applied genomic subtractive hybridization to two strains of P. fluorescens, Q8r1-96 and Q2-87, which differ in their ability to colonize wheat roots. Among 32 recovered Q8r1-96-specific loci was a clone dubbed ssh6, which proved to constitute part of a 22-kb prophage element that closely resembles prophage 01 of strain Pf-5 (Figs. 1 and 2; see Additional file 2). Like its counterpart, the ssh6 prophage from Q8r1-96 carries genes for a myovirus-like tail (orf10 through orf21), the lytic enzymes holin (hol) and endolysin (lys), and a Cro/CI-like repressor protein (prtR) (Fig. 1; see Additional file 2). Genes in the Q8r1-96 cluster that are not present in Pf-5 encode a colicin M-like bacteriocin (cma), a tail collar protein (orf23), and putative tail fiber proteins (orf22 and orf25). Interestingly, the colicin M-like ORF from the ssh6 prophage of Q8r1-96 also encodes an enzymatically active protein although the range of microorganisms sensitive to this bacteriocin is currently unknown (Dr. Dominique Mengin-Lecreulx, Institut de Biochimie et Biophysique Moléculaire et Cellulaire, Université Paris-Sud, Orsay, France; personal communication).

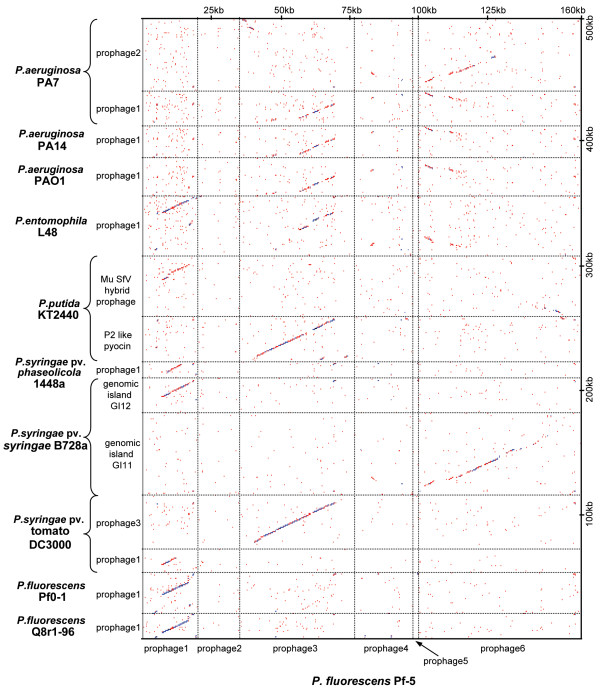

Figure 2.

Dot plot comparison of P. fluorescens Pf-5 prophages with similar prophage regions in the genomes of P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 [GenBank EU982300], P. fluorescens Pf0-1 [GenBank CP000094], P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 [24], P. syringae pv. syringae B728a [36], P. syringae pv. phaseolicola 1448a [37], P. putida KT2440 [25], P. aeruginosa PA01 [82], P. aeruginosa UCBPP-PA14 [35], and P. aeruginosa PA7 [GenBank CP000744]. All prophage sequences were extracted from genomes, concatenated and aligned using a dot plot function from OMIGA 2.0 with a sliding window of 45 and a hash value of 6. Genome regions used in the analysis encompass open reading frames with following locus tags: P. fluorescens Pf0-1 prophage1 – Pfl01_1135 through Pfl01_1173; P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 prophage1 – PSPTO_0569 through PSPTO_0587; P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 prophage3 – PSPTO_3385 through PSPTO_3432; P. syringae pv. syringae 728a genomic island GI11 – Psyr_2763 through Psyr_2846; P. syringae pv. syringae 728a genomic island GI12 – Psyr_4582 through Psyr_4608; P. syringae pv. phaseolicola 1448a prophage1 – PSPPH_0650 through PSPPH_0671; P. putida KT2440 P2 like pyocin – PP3031 through PP3066; P. putida KT2440 Mu SfV hybrid prophage – PP3849 through PP3920; P. entomophila L48 prophage1 – PSEEN4129 through PSEEN4186; P. aeruginosa PAO1 prophage1 – PA0610 through PA0648; P. aeruginosa PA14 prophage1 – PA14_07950 through PA14_08330; P. aeruginosa PA7 prophage1 – PSPA7_0754 through PSPA7_0789; P. aeruginosa PA7 prophage2 – PSPA7_2366 through PSPA7_2431.

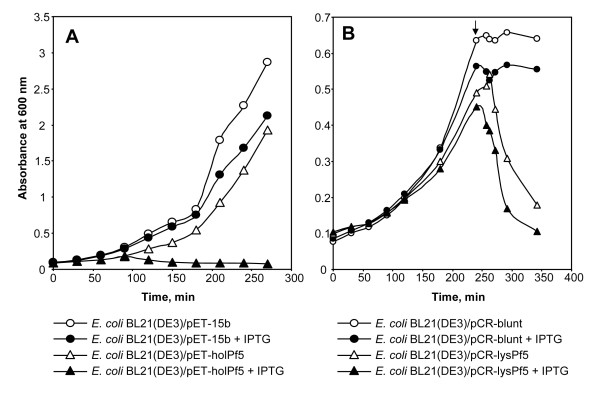

The homologous prophage elements from Pf-5 and Q8r1-96 have simple overall organization, lack integrase and head morphogenesis genes, and carry conserved regulatory, lytic and lambda-like tail morphogenesis genes also found in phage SfV of Shigella flexneri (Fig. 1). Taken together, the results of sequence analyses suggest that these regions are not simple prophage remnants but rather, are similar to F-type pyocins. F-type pyocins were first discovered in P. aeruginosa and represent a class of high molecular weight protease- and nuclease-resistant bacteriocins that resemble flexible and non-contractile tails of bacteriophages [18,19]. This notion is further supported by the fact that the putative lytic genes found within Pf-5 prophage 01 (Fig. 3) and Q8r1-96 (data not shown) seem to be fully functional. In non-filamentous bacteriophages and bacteriophage tail-like bacteriocins, the lytic activity is provided by the combined action of the small membrane protein holin and a cytoplamic muralytic enzyme, endolysin [19,20]. During phage-mediated cell lysis, holin permeabilizes the cytoplasmic membrane and allows endolysin, which lacks a secretory signal sequence, to gain access to peptidoglycan. To confirm that the prophage 01-like loci indeed encode functional holin and endolysin, we cloned genes PFL_1211 and PFL_1227 from Pf-5 and their counterparts from Q8r1-96 (Fig. 1) in Escherichia coli under the control of an inducible T7 promotor. As shown in Fig. 3, induction of both of the putative holin and endolysin genes by IPTG had a strong lethal effect on the host, resulting in rapid cell lysis. In accordance with the current model of action of holin and endolysin, the lethal effect of the endolysin encoded by PFL_1227 was not apparent unless the cytoplasmic membrane was destabilized by addition of small amount of chloroform to the induced E. coli culture (Fig. 3B). Gene induction experiments carried out with putative holin and endolysin genes from the ssh6 locus of Q8r1-96 had a similar lytic effect on E. coli (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Lytic activity associated with the prophage 01 of P. fluorescens Pf-5. Putative holin (PFL_1211) (A) and endolysin (PFL_1227) (B) genes encoded by prophage 01 from P. fluorescens Pf-5 were cloned in the plasmid vector pCR-Blunt (Invitrogen) under the control of the IPTG-inducible T7 promoter. Broth cultures of E. coli Rosetta/pLysS bearing the cloned holin and endolysin genes were induced with 3 mM IPTG and incubated with shaking for 5 hours while monitoring cell growth by measuring OD600. The arrow indicates the time of addition of chloroform to the endolysin-expressing culture. Two independent repetitions of the assay were carried out for each gene and yielded identical results (data not shown).

Interestingly, a prophage element found in the identical spot (between mutS and cinA) in the genome of P. fluorescens SBW25 http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/P_fluorescens has a similar overall organization but contains a P2-like bacteriophage tail cluster (orf5 through orf18) similar to that in phage CTX (Fig. 1), thus resembling another class of phage tail-like bacteriocins, the R-type pyocins of P. aeruginosa [19]. Furthermore, a homologous region from P. fluorescens Pf0-1 (CP000094) contains both the lambda-like and P2-like tail clusters (Fig. 1), making it similar to the hybrid R2/F2 pyocin locus from P. aeruginosa PAO1 [19]. The differences in organization of the putative phage tail-like pyocins among these prophages clearly indicate that the corresponding loci are subject to extensive recombination, with a possible recombination hotspot between two highly conserved DNA segments comprised of the phage repressor (prtR) and holin (hol) genes, and the endolysin (lys) gene (Fig. 1).

In strains Pf-5 and Q8r1-96, the putative prophage 01-like pyocins are integrated between mutS and the cinA-recA-recX genes (Fig. 1), which suggests that these elements might be activated during the SOS response, as is the putative prophage gene cluster integrated into the mutS/cinA region of P. fluorescens DC206 [21]. The mutS/cinA region is syntenic in several Gram-negative bacteria [22], and comparisons reveal that prophage 01-like elements occupy the same site in the genomes of P. fluorescens Pf0-1, P. fluorescens SBW25, and P. entomophila L48 [23], whereas unrelated prophages reside upstream of cinA in P. putida F1 (GenBank CP000712) and P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 [24]. The latter strain, as well as P. putida KT2440 [25], carry SfV-like bacteriophage tail assembly clusters elsewhere in the genome.

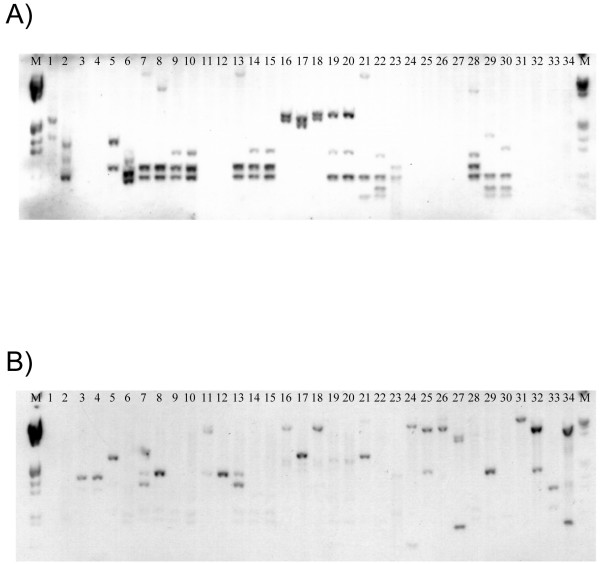

The putative F- and R-pyocins appear to be ubiquitously distributed among strains of P. fluorescens as illustrated by a screening experiment (Fig. 4) in which genomic DNA of different biocontrol strains was hybridized to probes targeting the lambda-like and P2-like bacteriophage tail gene clusters of Q8r1-96 and SBW25, respectively. The F- and R-pyocin-specific probes each strongly hybridized to DNA from 12 of 34 P. fluorescens strains, while the remaining 22 strains tested positive with both probes.

Figure 4.

Southern hybridization of DNA from 34 strains of P. fluorescens with probes targeting F-pyocin- and R-pyocin-like bacteriophage tail assembly genes. Total genomic DNA from each strain was digested with EcoRI and PstI restriction endonucleases, separated by electrophoresis in a 0.8% agarose gel, and transferred onto a BrightStar-Plus nylon membrane. The blots were hybridized with biotin-labeled probes prepared from P. fluorescens strains Q8r1-96 (A) and SBW25 (B) targeting the SfV-like (A) and CTX-like (B) bacteriophage tail assembly genes, respectively. Strains screened in the experiment are: P. fluorescens CHA0 [83], 1; P. fluorescens Pf-5 [5], 2; P. fluorescens Q2-87 [84], 3; P. fluorescens Q2-1 [84], 4; P. fluorescens STAD384 [85], 5; P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 [74], 6; P. fluorescens MVW1-1 [86], 7; P. fluorescens FTAD1R34 [85], 8; P. fluorescens ATCC49054 [87], 9; P. fluorescens Q128-87 [85], 10; P. fluorescens OC4-1 [85], 11; P. fluorescens FFL1R9 [85], 12; P. fluorescens Q2-5 [84], 13; P. fluorescens QT1-5 [84], 14; P. fluorescens W2-6 [84], 15; P. fluorescens Q2-2 [84], 16; P. fluorescens Q37-87 [84], 17; P. fluorescens QT1-6 [84], 18; P. fluorescens JMP6 [84], 19; P. fluorescens JMP7 [84], 20; P. fluorescens FFL1R18 [84], 21; P. fluorescens CV1-1 [84], 22; P. fluorescens FTAD1R36 [84], 23; P. fluorescens FFL1R22 [84], 24; P. fluorescens F113 [88], 25; P. fluorescens W4-4 [84], 26; P. fluorescens D27B1 [84], 27; P. fluorescens HT5-1 [84], 28; P. fluorescens 7MA12 [86], 29; P. fluorescens MVP1-4 [86], 30; P. fluorescens MVW1-1 [86], 31; P. fluorescens MVW4-2 [86], 32; P. fluorescens ATCC17400 [89], 33; P. fluorescens SBW25 [90], 34.

Prophage 03 of P. fluorescens Pf-5

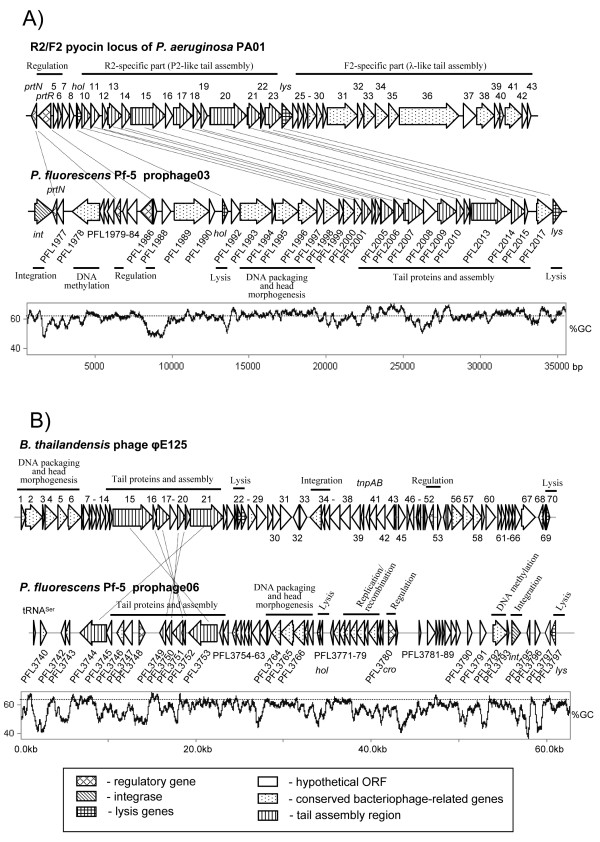

A second large prophage, prophage 03, spans 33.5 kb (Fig. 5A; see Additional file 3) of the Pf-5 genome. Closely related prophages exist in the genomes of P. putida KT2440 [25] and P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 [24] (Fig. 2) but were not found in P. fluorescens strains Pf0-1 or SBW25. Prophage 03 is a chimeric element that contains a siphovirus head morphogenesis region and a myovirus-like tail assembly region (Fig. 5A). The prophage also carries a putative integrase gene (PFL_1976) that encodes an enzyme similar to shufflon recombinases such as the Rci recombinase from plasmid R64 [26], a gene involved in DNA modification (PFL_1978), and a gene for a cytosine-specific methylase (PFL_1979). Genes encoding a LexA-like repressor (PFL_1986), a putative single strand binding protein (PFL_1989), and two genes (PFL_1976 and PFL_1982) with similarity to the pyocin transcriptional activator prtN also are present in this region. Holin (PFL_1991) and endolysin (PFL_2018) genes flank a region containing DNA packaging and head morphogenesis and tail assembly genes. The P2-like tail assembly region closely resembles the R2-specific part of R2/F2 pyocin locus of P. aeruginosa PA01 [19] (Fig. 5A) and includes genes encoding a tail sheath protein (PFL_2009), a tape measure protein (PFL_2013), a major tail tube protein (PFL_2010), baseplate assembly proteins (PFL_2002 and PFL_2003), and a tail fiber protein (PFL_2007). This region also contains genes involved in head morphogenesis (PFL_1993–1998) that are not present in the R-part of R2/F2-type pyocin cluster of P. aeruginosa PA01. Therefore, prophage 03 may represent the genome of a temperate bacteriophage rather than an R-type pyocin.

Figure 5.

Comparison of genetic organization of prophages 03 (A) and 06 (B) to that of R2/F2 pyocin locus from P. aeruginosa PA01 [19]and B. thailandensis phage φE125, respectively. Predicted open reading frames and their orientation are shown by arrows along with a 300-bp sliding window plot of G+C content for the prophage 03 with dotted line tracing the average G+C content (63%) of Pf-5 genome. Predicted ORFs are shaded according to their functional category. Homologous ORFs are connected with lines.

Prophage 06 and other prophage regions of P. fluorescens Pf-5

Prophage 06 is the largest prophage region of P. fluorescens Pf-5 and encodes a 56-kb temperate lambdoid phage integrated into tRNASer(see Additional file 4). It is mosaic in nature with no homologues present in strains Pf0-1 or SBW25. P. fluorescens Pf-5 carries four genomic copies of tRNASer, of which tRNASer(2) and tRNASer(3) are associated with prophages carrying integrases of different specificity (see Additional file 5). The anticodon, V- and T-loops of tRNASer(2) are parts of the 104-bp putative attB site of prophage 06, whereas the T-loop of tRNASer(3) forms part of the 60-bp putative attachment site of prophage 02. The latter is a prophage remnant that spans 8.4 kb and consists of a gene encoding an ATP-dependent nuclease (PFL_1842) and a phage integrase gene with two internal frameshift mutations (see Additional file 6). The mobility of prophage 06 probably is mediated by a lambda-type integrase encoded by PFL_3794, which resides adjacent to the putative attR site. Prophage 06 contains gene modules that are involved in head morphogenesis (capsid proteins PFL_3764 and PFL_3765), DNA packaging (terminase PFL_3766), DNA recombination (a NinG-like protein, PFL_3773 and a putative NHN-endonuclease, Orf1) and tail morphogenesis (tail tip fiber proteins PFL_3744 and PFL_3751, tail length tape measure protein PFL_3753, and minor tail proteins PFL_3749, PFL_3750, and PFL_3752). The tail assembly module resembles the corresponding region from Burkholderia thailandensis bacteriophage φE125 [27], although in prophage 06 the module is split by the integration of four extra genes (Fig. 5B). Prophage 06 also contains a regulatory circuit with genes for a Cro/C1 repressor protein (PFL_3780) and two putative antirepressor proteins (PFL_3747 and PFL_3746); a gene for a putative cytosine C5-specific methylase (PFL_3792); and lysis genes encoding holin (PFL_3770) and endolysin (PFL_3798). However, since the endolysin gene is localized beyond the putative attR site it is not clear whether it represents part of the prophage 06 genome or a remnant from integration of a different phage (see Additional file 4). Finally, prophage 06 contains two genes, PFL_3740 and PFL_3796, which probably arose through gene duplication and encode putative conserved phage-related proteins that are 88% identical to one another.

Prophages 04 and 05 are prophage remnants with reduced size and/or complexity that carry several mutated phage-related genes (Tables 1, see Additional files 7 and 8). Prophage 04 (13.5-kb) has an average G+C content of 56.3% and contains a putative phage integrase gene adjacent to tRNAPro (1). It also carries two genes (PFL_2122 and PFL_2123) that encode minor tail assembly proteins, a gene encoding Cro/C1 repressor, and the bacteriocin gene llpA1 (PFL_2127). Interestingly, the repressor gene and llpA1 are highly similar to their counterparts from prophage 01, suggesting that they arose via gene duplication. Prophage 05, a 2.6-kb prophage remnant, has a G+C content of 55.3% and carries genes encoding a truncated phage integrase and a putative phage tail protein (PFL_3464) (see Additional file 8). The region is flanked by 84-bp direct repeats, one of which probably represents the attB site and partially overlaps with the anticodon and T loops of tRNACys.

Genomic island PFGI-1

Location and integrase

Integrative conjugative elements (ICEs) are a rapidly growing class of strain-specific mosaic MGEs that can profoundly impact the adaptation and evolution of bacterial species [28]. ICEs vary in size from 10 to 500 kb, encode for mobility loci, and commonly exhibit anomalous G+C content and codon usage. Typical ICEs carry phage-like integrase genes that allow for site-specific integration, most often into tRNA genes, as well as plasmid-like replication and recombination functions and conjugative machinery that contributes to horizontal transfer. Finally, they often carry gene clusters encoding functions that are not essential for the host but that provide an advantage under particular environmental conditions. There is increasing evidence that ICEs derived from plasmids and encoding host-specific pathogenicity traits as well as traits essential for survival in natural habitats are widely distributed among members of the genus Pseudomonas [29-34].

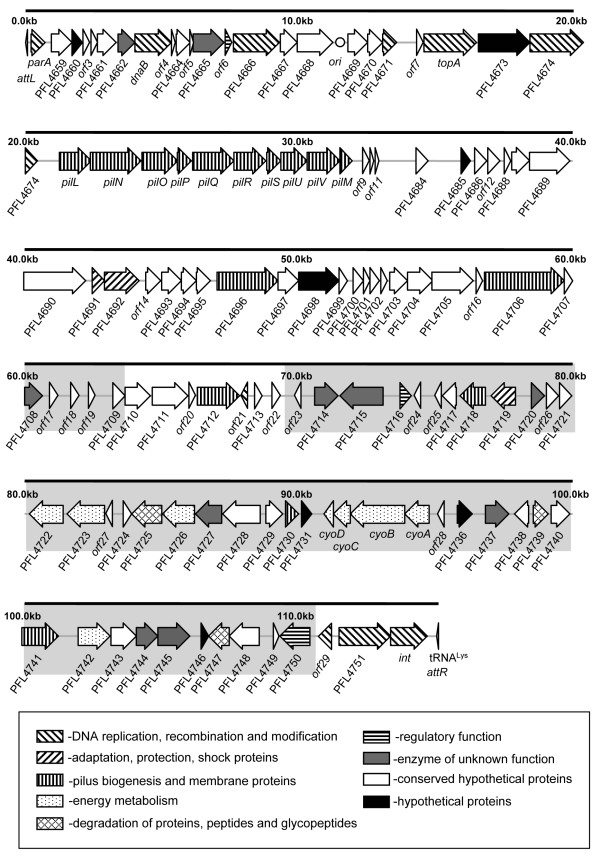

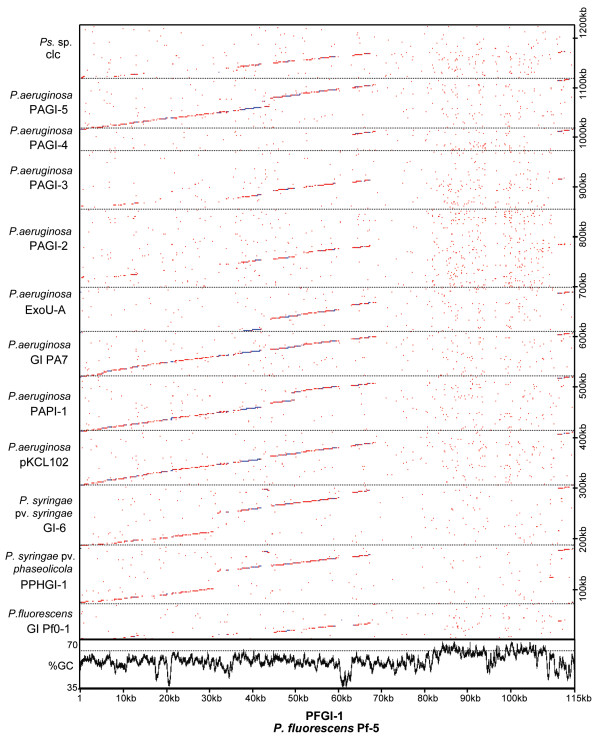

P. fluorescens Pf-5 harbors a 115-kb mobile genomic island 01, or PFGI-1 (Fig. 6, see Additional file 9), that resembles a large self-transmissible plasmid and exemplifies the first large plasmid-derived MGE found in P. fluorescens. Of 96 putative PFGI-1 coding sequences (CDSs), 50 were classified as hypothetical or conserved hypothetical genes, and 55 were unique to Pf-5 and absent from the genomes of strains SBW25 and Pf0-1 (Fig. 7). PFGI-1 is integrated into the tRNALys gene (one of two genomic copies) situated next to PFL_4754, a CDS with similarity to exsB. Interestingly, this region has conserved synteny and probably represents an integration "hot spot" for CGIs in Pseudomonas spp., since putative integrase genes also are found adjacent to exsB in P. aeruginosa UCBPP-PA14 [35], P. putida KT2440 [25], P. syringae pv. syringae B728a [36] and P. syringae pv. phaseolicola 1448A [37]. PFGI-1 spans 115,118 bp and is flanked by 49-bp direct repeats that include 45 bp of the 3' end of tRNALys and represent a putative attB site. A recent survey of phage and tRNA integration sites by Williams [38] revealed that sublocation of attB within a tRNA gene correlates with subfamilies of tyrosine recombinases. According to this classification, the putative attB site of PFGI-1 falls into class IA since it encompasses both the T and anticodon loops of tRNALys. The integration of PFGI-1 probably is controlled by a phage-like tyrosine integrase encoded by PFL_4752 located 335 bp upstream from tRNALys.

Figure 6.

Organization of genomic island PFGI-1. Predicted open reading frames are shaded according to their category and their orientation is shown by arrows. DNA regions unique to P. fluorescens Pf-5 and not found in closely related GIs from other Pseudomonas spp. are indicated by grey shading.

Figure 7.

Dot plot comparison of genomic island PFGI-1 with related genomic islands from other Pseudomonas spp. Sequences of GI from P. fluorescens Pf0-1 [GenBank acc. CP000094; locus tags Pfl_O1_2993 through Pfl_O1_R50], PPHGI-1 from P. syringae pv. phaseolicola 1302A [33], GI-6 from P. syringae pv. syringae B728a [36], pKCL102 from P. aeruginosa C [30], PAPI-1 from P. aeruginosa UCBPP-PA14 [32], GI from P. aeruginosa PA7 [GenBank acc. CP000744; locus tags PSPA7_4437 through PSPA7_4531], ExoU-A island from P. aeruginosa 6077 [31], PAGI-2 and PAGI-4 from P. aeruginosa C [29], PAGI-3 from P. aeruginosa SGM17M [29], PAGI-5 from P. aeruginosa PSE9 [GenBank acc. EF611301], and clc element from Pseudomonas sp. B13 [34] were concatenated and aligned with PFGI-1 using a dot plot function from OMIGA 2.0 with sliding window of 45 and hash value of 6. Lower panel shows a 500-bp sliding window plot of G+C content for PFGI-1 with dotted line tracing the average G+C content (63%) of Pf-5 genome.

Genes involved in plasmid replication, recombination, conjugative transfer, and possible origin of PFGI-1

Whether PFGI-1 exists in strain Pf-5 or in any other Pseudomonas host as an episome is not known. However, the first two-thirds of PFGI-1 contain putative plasmid replication, partitioning and conjugation genes that are readily aligned at the DNA level with those from plasmid pKLC102 of P. aeruginosa C [30]. The putative origin of replication, oriV, is situated immediately upstream of PFL_4669 and spans about 1,100 bp. Plasmid origins of replication often contain arrays of specific ~20 bp repeats, called iterons, that serve as binding sites for the cognate replication initiator Rep protein and are involved in replication and partitioning [39,40]. In addition to plasmid-specific iterons, some plasmid origins contain A+T-rich repeats where host replication initiation factors bind and open DNA, as well as repeats serving as binding sites for the host DnaA initiator protein. The putative oriV from PFGI-1 exhibits typical features of a plasmid replication origin. The first half is A+T-rich and has four conserved direct repeats of a perfect 23-bp palindrome (5'-CTGAGTTCGGAATCCGAACTCAGT-3'). The second half is represented by a G+C-rich stretch that overlaps with the region between PFL_4668 and PFL_4669 and contains four conserved 46-bp direct repeats, each of which includes an imperfect 21-bp inverted repeat (5'-AGTGTTGTGGGCCACACCACT-3'). The putative oriV is flanked by genes encoding proteins involved in plasmid replication, recombination and segregation, including putative homologues of DnaB and ParB (PFL_4663 and PFL_4666), a nucleoid associated protein (PFL_4665), topoisomerase TopA (PFL_4672), a putative helicase (PFL_4674), a single-strand binding protein (PFL_4671), and a partitioning protein, ParA (Fig. 6). PFGI-1 does not encode a Rep protein, and it is not clear whether it replicates by a theta-type or strand displacement mechanism, although the latter has been suggested for pKLC102 [30]. Like some conjugative plasmids, PFGI-1 carries homologues of the stress-inducible genes umuC (PFL_4692) and umuD (PFL_4691), which encode a putative lesion bypass DNA polymerase and a related accessory protein, respectively. Such genes may be involved in plasmid DNA repair and umuDC-mediated mutagenesis, which could allow plasmids to adapt more quickly to new bacterial hosts [41].

PFGI-1 also contains a cluster of 10 genes, pilLNOPQRSTUVM (PFL_4675 through PFL_4683) (Fig. 6), that spans over 10 kb and closely resembles part of the pil region from the self-transmissible E. coli plasmid R64 [42]. In E. coli, these genes are involved in production of thin flexible sex pili required for mating and transfer of R64 in liquid media. The similarity between the pil clusters of R64 and PFGI-1 suggests that the latter encode mating pili rather than type IV pili involved in bacterial twitching motility, adherence to host cells, biofilm formation and phage sensitivity [43]. P. fluorescens Pf-5 has the capacity to produce type IV pili, and the corresponding biosynthetic genes are located in at least three clusters found outside of PFGI-1. The PFGI-1 pil cluster contains genes for pilin protein PilS (PFL_4680), prepilin peptidase PilU (PFL_4681), outer membrane protein PilN (PFL_4676), nucleotide binding protein PilQ (PFL_4678), integral membrane protein PilR (PFL_4679), and pilus adhesin PilV (PFL_4682). Unlike R64, PFGI-1 does not include a shufflon region that determines recipient specificity in liquid matings via generation of different adhesin types [42,44]. Finally, PFGI-1 carries genes encoding proteins that may be involved in conjugal DNA transfer. PFL_4696 and PFL_4706 encode for TraG-like coupling proteins that may function as membrane-associated NTPases, which during conjugation would mediate transport of DNA covalently linked to a putative relaxase protein (the product of PFL_4751).

Recent studies have demonstrated that ICEs are a major component of a flexible gene pool of different lineages of Gram-negative Proteobacteria [45-47]. Metabolically versatile members of the Pseudomonadaceae are no exception, with ICEs having been identified among strains of P. aeruginosa [29-32], P. syringae [36,48], and P. fluorescens [49]. Comparison of PFGI-1 with islands from other Pseudomonas spp. reveals at least six highly conserved gene clusters (Fig. 7). These regions include: genes encoding partitioning (parA and parB) and single-strand binding (ssb) proteins, pilot proteins (traG), relaxase (PFL_4751), integrase (int), the putative origin of replication, and at least 26 conserved hypothetical ORFs. The pil operon is another syntenic cluster shared by PFGI-1 and the pathogenicity islands pKCL102 and PAPI-1, and PPHGI-1 of P. aeruginosa and and GI-6 of P. syringae. These findings further confirm the results of a recent study by Mohd-Zain et al. [47], who compared the evolutionary history of 33 core genes in 16 GIs from different β- and γ-Proteobacteria and found that despite their overall mosaic organization, many genomic islands including those from Pseudomonas spp. share syntenic core elements and evolutionary origin.

Putative phenotypic traits encoded by PFGI-1

As a rule, ICEs carry unique genes that reflect the lifestyles of their hosts. In P. aeruginosa and P. syringae, ICEs encode pathogenicity factors that allow these bacteria to successfully colonize a variety of hosts, as well as metabolic, regulatory, and transport genes that most probably enable them to thrive in diverse habitats [29,30,32,33,36,50]. An unusual self-transmissible ICE, the clc element from the soil bacterium Pseudomonas sp. B13, enables its host to metabolize chlorinated aromatic compounds [34,46,51].

In PFGI-1, a unique ~35 kb DNA segment that is absent from pKLC102 and other closely related ICEs (Figs. 6 and 7) encodes "cargo" genes that are not immediately related to integration, plasmid maintenance or conjugative transfer. Some of these genes are present in a single copy and do not have homologues elsewhere in the Pf-5 genome. About half of PFGI-1 "cargo" genes also are strain-specific and have no homologues in genome of P. fluorescens Pf0-1.

How could genes encoded by PFGI-1 contribute to the survival of P. fluorescens Pf-5 in the rhizosphere? Some of them might facilitate protection from environmental stresses. For example, nonheme catalases similar to the one encoded by PFL_4719 (Fig. 6) are bacterial antioxidant enzymes containing a dimanganese cluster that catalyzes the disproportionation of toxic hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen [52]. PFGI-1 also carries a putative cardiolipin synthase gene (PFL_4745) and a cluster of four genes, cyoABCD (PFL_4732 through PFL_4735), that encode components of a cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase complex. In P. putida, cardiolipin synthase was implicated in adaptation to membrane-disturbing conditions such as exposure to organic solvents [53], whereas the cytochrome o oxidase complex was shown to be highly expressed under low-nutrient conditions such as those found in the rhizosphere, and to play a crucial role in a proton-dependent efflux system involved in toluene tolerance [54,55]. Finally, PFGI-1 cargo genes with predicted regulatory functions include a GGDEF-motif protein (PFL_4715), a two-component response regulator with a CheY domain (PFL_4716) and a sensor histidine kinase (PFL_4750). Although the exact role of these genes remains unknown, the GGDEF domain proteins represent an emerging class of bacterial regulators involved in the synthesis of bis-(3'-5')-cyclic dimeric GMP, a global signaling messenger [56], and two-component signal-transduction systems are widely employed by Gram-negative bacteria to sense changes in the environment and appropriately modulate the expression of certain genes [57].

Genomic island PFGI-2

Genomic island 02, or PFGI-2, spans 16.8 kb and has an average G+C content of 51.5%. It is flanked by imperfect 51-bp direct repeats, one of which partially overlaps with tRNALeu(6) and probably represents the attB site (see Additional file 10). Although P. fluorescens Pf-5 does not have a type III protein secretion pathway, approximately half of PFGI-2 (i.e. an 8.1-kb DNA segment spanning genes PFL_4977 to PFL_4980) closely resembles a gene cluster found in the exchangeable effector locus (EEL) of a tripartite type III secretion pathogenicity island (T-PAI) from the plant pathogen P. viridiflava strain ME3.1b [58] (see Additional file 10). Even the presence of a putative phage integrase gene (PFL_4977) (see Additional files 5 and 10) and integration into tRNALeu immediately downstream of the tgt and queA genes is typical of T-PAI islands from P. viridiflava [58] and P. syringae [59]. In addition to T-PAI-like genes, PFGI-2 contains a putative phage-related MvaT-like (PFL_4981) transcriptional regulator, a superfamily II helicase (PFL_4979), a putative nucleoid-associated protein (PFL_4983), and a putative nuclease (PFL_4984). None of the aforementioned homologues of PFGI-2 genes in P. viridiflava have been characterized experimentally to date, making in difficult to deduce the function, if any, of this genome region. It also is possible that PFGI-2 is inactive and simply represents a T-PAI-like remnant anchored in the Pf-5 chromosome.

Transposons of P. fluorescens Pf-5

Unlike the genomes of other Pseudomonas spp., that of P. fluorescens Pf-5 is devoid of IS elements and contains only one CDS (PFL_2698) that appears to encode a full-length transposase. Three other transposase-like CDSs (PFL_1553, PFL_3795, and PFL_2699) found in the Pf-5 genome contain frameshifts or encode truncated proteins. PFL_2698 and PFL_2699 encode IS66-like transposases and are found within a large cluster (PFL_2662 through PFL_2716) of conserved hypothetical genes. Corrupted transposases encoded by PFL_1553 and PFL_3795 belong to the IS5 family and are associated with gene clusters encoding a putative filamentous hemagglutinin and prophage 06, respectively.

Conclusion

Recent analyses have revealed that most sequenced bacterial genomes contain prophages formed when temperate bacteriophages integrate into the host genome [60]. In addition to genes encoding phage-related functions, many prophages carry non-essential genes that can dramatically modify the phenotype of the host, allowing it to colonize or survive in new ecological niches [60,61]. Our knowledge of the ecological role of Pseudomonas prophages is limited, but data from other bacterial species suggest ways in which prophage regions could affect the survival of P. fluorescens Pf-5 in natural habitats.

Temperate bacteriophages similar to those encoded by prophages 03 and 06 are capable of development through both lysogenic and lytic pathways, and the presence of prophages can protect the host from superinfection by closely related bacteriophages [60]. On the other hand, the lytic pathway ultimately results in phage-induced host cell lysis, and it has been reported that the presence of virulent bacteriophages can adversely affect rhizosphere-inhabiting strains of P. fluorescens [62-64]. Similarly bacteriophage tail-like bacteriocins such as the one encoded by prophage 01 are capable of killing both closely and more distantly related strains of bacteria, presumably through destabilization of the cell membrane [65-69].

Temperate bacteriophages and bacteriophage-like elements also are an important part of the bacterial flexible gene pool and actively participate in horizontal gene transfer [60,70]. Among the putative lysogenic conversion genes in P. fluorescens Pf-5 are two copies of llpA, located adjacent to prophages 01 and 04. These genes encode low-molecular weight bacteriocins resembling plant mannose-binding lectins that kill sensitive strains of Pseudomonas spp. via a yet-unidentified mechanism [71]. The fact that both llpA copies reside near prophage repressor genes, as well as the involvement of a recA-dependent SOS response in LlpA production by a different strain of Pseudomonas [72], suggests that the association of llpA genes with prophages is not accidental and that the prophages may be involved in the regulation of bacteriocin production in P. fluorescens Pf-5.

The analysis of MGEs revealed at least 66 CDSs not present in the original Pf-5 genome annotation (data are summarized in supplemental Tables). The bulk of these newly predicted CDSs fall in the category of conserved hypothetical genes of bacterial or phage origin. Predicted products of the remaining novel CDSs exhibit similarity to proteins of diverse enzymatic, regulatory, and structural functions and include a phage integrase, an ATP-dependent DNA ligase, an endonuclease, plasmid partitioning and stabilization proteins, a NADH-dependent FMN reductase, an acytransferase, a PrtN-like transcriptional regulator, a Com-like regulatory protein, a P-pilus assembly and an integral membrane protein.

Taken together, the analyses of six prophage regions and two GIs in the Pf-5 genome indicate that these structures have evolved via exchange of genetic material with other Pseudomonas spp. and extensive recombination. Transposition is unlikely to have played a major role in this evolution, as the genome of Pf-5 is nearly devoid of transposons and IS elements that are common in certain other Pseudomonas genomes. Most of the 260 kb comprising MGEs in the Pf-5 genome is similar to corresponding regions in the genomes of other Pseudomonas spp. Nevertheless, the MGEs also include regions unique to the Pf-5 genome that could contribute to the bacterium's fitness in the soil or rhizosphere.

Methods

Strains and plasmids

Wild type variants of P. fluorescens Pf-5 [5], P. fluorescens SBW25 [73], and P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 [74] were used in the study. Pseudomonas strains were grown at 28°C in King's B medium [75], while E. coli strains were grown in LB [76] or 2xYT [76] at 25°C or 37°C. When appropriate, antibiotic supplements were used at the following concentrations: tetracycline, 12.5 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 35 μg/ml; and ampicillin, 100 μg/ml.

DNA manipulations and sequence analyses

Plasmid DNA isolation, restriction enzyme digestion, agarose gel electrophoresis, ligation, and transformation were carried out using standard protocols [76]. All primers were developed with Oligo 6.65 Software (Molecular Biology Insights, West Cascade, Colo.), and routine PCR amplifications were performed with Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, Wisc.) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Sequencing of prophage 01 from P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 was carried out essentially as described by Mavrodi et al. [77]. Briefly, the Q8r1-96 gene library was screened by PCR with oligonucleotide primers col1 (5' GCT GCT GGG CAA TGG TAA CAC 3') and col2 (5' CTG CCG ACT GCT CAC CTA TC 3') and a positive cosmid clone was shotgun sequenced by using the EZ::TN™ <Kan-2> transposition system (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, Wisc.). DNA sequencing was carried out by using an ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), and sequence data were compiled and analyzed with Vector NTI 9.1.0 (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, Calif.) and OMIGA 2.0 (Accelrys, San Diego, Calif.) software packages. Database searches for similar protein sequences were performed using the NCBI's BLAST network service, and searches against PROSITE, Profile, HAMAP, and Pfam collections of protein motifs and domains were carried out by using the MyHits Internet engine [78]. Signal peptides were predicted with SignalP v. 3.0. [79]. The nucleotide sequence of prophage 01 from P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 has been deposited in GenBank under accession number EU982300.

DNA hybridization

The 3.12-kb prophage 01 probe was amplified by PCR from P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 genomic DNA with the oligonucleotide primers orf11-1 (5' CAT TCG TGT GCC GCT GTT CTA 3') and orf14-2 (5' TGA CCA GGC GAA CAG CGT CTG 3'). The 1.79-kb P. fluorescens SBW25-specific prophage 01 probe was amplified from genomic DNA of SBW25 with oligonucleotides SBW3 (5' GAA CTC ACC AGC GTC CTT AAC 3') and SBW4 (5' GGG CAG CTC CTT GGT GAA GTA 3'). Amplification was carried out with Expand Long DNA polymerase (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) according to manufacturer's recommendations. The cycling program included a 2-min initial denaturation at 94°C followed by 25 cycles of 94°C for 10 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, and 68°C for 3 min. Amplified DNA was gel-purified with a QIAEX II gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, Calif.) and labeled with the Biotin High Prime System (Roche Applied Science). Genomic DNA was purified using a cetyltrimethylammonium bromide miniprep protocol [76], digested with EcoRI and PstI, separated by electrophoresis in a 0.8% agarose gel, and transferred onto a BrightStar-Plus nylon membrane (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX) in 0.4 M NaOH. The membranes were pre-hybridized and hybridized at 58°C in a solution containing 5 × SSC [80], 4 × Denhardt's solution [80], 0.1% SDS, and 300 μg per ml of denatured salmon sperm DNA (Sigma). After hybridization, the membranes were washed twice in 2 × SSC, 0.1% SDS at room temperature, twice in 0.2 × SSC, 0.1% SDS at room temperature, and once in 0.2 × SSC, 0.1% SDS at 60°C.

Lytic assays

Full-length hol genes from strains Pf-5 and Q8r1-96 were amplified by using KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase (Novagen, Inc.) and oligonucleotide primer pairs holupPf5 (5' AGG GAC CTC TAG AAA CAT CGT TA 3') – holowPf5 (5' TTT TGG ATC CGG TGA GTC AAG GCT G 3') and hol-xba (5' GAC CAG TCT AGA CAT GCT CAT CA 3') – hol-low (5' TTT TGG ATC CGC GGT ATC GCT T 3'), respectively. Full-length lys genes from Pf-5 and Q8r1-96 were amplified by using primer sets lysupPf5 (5' CGC CAT TCT AGA TTA CTG AAC AA 3') – lyslowPf5 (5' TTT TGG ATC CGC AGG ACC TTC AGA C 3') and lysQ8-up (5' CGG ACA TCT AGA ATC ATG CAC TTG 3') – tail13 (5' GCC GCT TGG GTG ATT TGA TT 3'), respectively. The cycling program included a 2-min initial denaturation at 94°C followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 15 sec, 59°C for 30 sec, and 68°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 68°C for 3 min. PCR products were gel-purified and cloned into the SmaI site of the plasmid vector pCR-Blunt (Invitrogen) under the control of the T7 promoter. The resultant plasmids were single-pass sequenced to confirm the integrity of cloned genes and electroporated into E. coli Rosetta/pLysS (Novagen) with a Gene Pulser II system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). Plasmid-bearing E. coli clones were selected overnight on LB agar supplemented with ampicillin and chloramphenicol, and suspended in 2xYT broth supplemented with antibiotics to give an OD600 of 0.1. After incubation with shaking for one hour at room temperature, gene expression was induced in the broth cultures with 3 mM IPTG. The induced cultures were incubated with shaking for another 5 hours and the cell density was monitored by measuring OD600 every 30 min. To disrupt cell membranes in endolysin-expressing cultures, a drop of chloroform was added after four hours of induction. Two independent repetitions were performed with each strain.

Authors' contributions

DVM was responsible for conception of the study, experimental design, data collection, and analysis. LST, ITP and JEL participated in data analysis and preparation of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Sequence analysis of prophage 01 of P. fluorescens Pf-5. Table containing annotation of mobile genetic element prophage 01 in the genome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. The following information is provided for each open reading frame: locus tag number, gene name, genome coordinates, length and molecular weight of encoded protein, sequence of putative ribosome binding site, description of the closest GenBank match plus blast E-value, list of functional domains and predicted function.

Sequence analysis of prophage 01 of P. fluorescens Q8r1-96. Table containing annotation of mobile genetic element prophage 01 in the genome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Q8r1-96. The following information is provided for each open reading frame: locus tag number, gene name, genome coordinates, length and molecular weight of encoded protein, sequence of putative ribosome binding site, description of the closest GenBank match plus blast E-value, list of functional domains and predicted function.

Sequence analysis of prophage 03 of P. fluorescens Pf-5. Table containing annotation of mobile genetic element prophage 03 in the genome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. The following information is provided for each open reading frame: locus tag number, gene name, genome coordinates, length and molecular weight of encoded protein, sequence of putative ribosome binding site, description of the closest GenBank match plus blast E-value, list of functional domains and predicted function.

Sequence analysis of prophage 06 of P. fluorescens Pf-5. Table containing annotation of mobile genetic element prophage 06 in the genome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. The following information is provided for each open reading frame: locus tag number, gene name, genome coordinates, length and molecular weight of encoded protein, sequence of putative ribosome binding site, description of the closest GenBank match plus blast E-value, list of functional domains and predicted function.

Sequence analysis of putative integrase genes from P. fluorescens Pf-5. Table containing annotation of putative integrase genes present in the genome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. The following information is provided for each open reading frame: locus tag number, gene name, genome coordinates, length and molecular weight of encoded protein, sequence of putative ribosome binding site, description of the closest GenBank match plus blast E-value, list of functional domains and predicted function.

Sequence analysis of prophage 02 of P. fluorescens Pf-5. Table containing annotation of mobile genetic element prophage 02 in the genome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. The following information is provided for each open reading frame: locus tag number, gene name, genome coordinates, length and molecular weight of encoded protein, sequence of putative ribosome binding site, description of the closest GenBank match plus blast E-value, list of functional domains and predicted function.

Sequence analysis of prophage 04 of P. fluorescens Pf-5. Table containing annotation of mobile genetic element prophage 04 in the genome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. The following information is provided for each open reading frame: locus tag number, gene name, genome coordinates, length and molecular weight of encoded protein, sequence of putative ribosome binding site, description of the closest GenBank match plus blast E-value, list of functional domains and predicted function.

Sequence analysis of prophage 05 of P. fluorescens Pf-5. Table containing annotation of mobile genetic element prophage 05 in the genome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. The following information is provided for each open reading frame: locus tag number, gene name, genome coordinates, length and molecular weight of encoded protein, sequence of putative ribosome binding site, description of the closest GenBank match plus blast E-value, list of functional domains and predicted function.

Sequence analysis of island 01 of P. fluorescens Pf-5. Table containing annotation of mobile genetic element island 01 in the genome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. The following information is provided for each open reading frame: locus tag number, gene name, genome coordinates, length and molecular weight of encoded protein, sequence of putative ribosome binding site, description of the closest GenBank match plus blast E-value, list of functional domains and predicted function.

Sequence analysis of island 02 of P. fluorescens Pf-5. Table containing annotation of mobile genetic element island 02 in the genome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. The following information is provided for each open reading frame: locus tag number, gene name, genome coordinates, length and molecular weight of encoded protein, sequence of putative ribosome binding site, description of the closest GenBank match plus blast E-value, list of functional domains and predicted function.

Contributor Information

Dmitri V Mavrodi, Email: mavrodi@mail.wsu.edu.

Joyce E Loper, Email: Joyce.Loper@ARS.USDA.GOV.

Ian T Paulsen, Email: ipaulsen@cbms.mq.edu.au.

Linda S Thomashow, Email: thomashow@wsu.edu.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Olga Mavrodi for help with the screening of Q8r1-96 gene library for ssh6-positive cosmid clones. This work was supported by the US Department of Agriculture, National Research Initiative, Competitive Grants Program (grants number 2001-52100-11329, 2003-35319-13800 and 2003-35107-13777).

References

- Brussow H, Canchaya C, Hardt WD. Phages and the evolution of bacterial pathogens: from genomic rearrangements to lysogenic conversion. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:560–602. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.560-602.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn AM, Boltner D. When phage, plasmids, and transposons collide: genomic islands, and conjugative- andmobilizable-transposons as a mosaic continuum. Plasmid. 2002;48:202–12. doi: 10.1016/S0147-619X(02)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen IT, Press CM, Ravel J, Kobayashi DY, Myers GSA, Mavrodi DV, DeBoy RT, Seshadri R, Ren QH, Madupu R, Dodson RJ, Durkin AS, Brinkac LM, Daugherty SC, Sullivan SA, Rosovitz MJ, Gwinn ML, Zhou LW, Schneider DJ, Cartinhour SW, Nelson WC, Weidman J, Watkins K, Tran K, Khouri H, Pierson EA, Pierson LS, Thomashow LS, Loper JE. Complete genome sequence of the plant commensal Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Nature Biotechnol. 2005;23:873–878. doi: 10.1038/nbt1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross H, Stockwell VO, Henkels MD, Nowak-Thompson B, Loper JE, Gerwik WH. The genomisotopic approach: a systematic method to isolate products of orphan biosynthetic gene clusters. Chemistry and Biology. 2007. in press . [DOI] [PubMed]

- Howell CR, Stipanovic RD. Control of Rhizoctonia solani in cotton seedlings with Pseudomonas fluorescens and with an antibiotic produced by the bacterium. Phytopathology. 1979;69:480–482. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-69-480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howell CR, Stipanovic RD. Suppression of Pythium ultimum induced damping-off of cotton seedlings by Pseudomonas fluorescens and its antibiotic pyoluteorin. Phytopathology. 1980;70:712–715. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-70-712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus J, Loper JE. Lack of evidence for a role of antifungal metabolite production by Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 in biological control of Pythium damping-off of cucumber. Phytopathology. 1992;82:264–271. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-82-264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus J, Loper JE. Characterization of a genomic region required for production of the antibiotic pyoluteorin by the biological control agent Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:849–854. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.3.849-854.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak-Thompson B, Chaney N, Wing JS, Gould SJ, Loper JE. Characterization of the pyoluteorin biosynthetic gene cluster of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2166–2174. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2166-2174.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak-Thompson B, Gould SJ, Kraus J, Loper JE. Production of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol by the biocontrol agent Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Can J Microbiol. 1994;40:1064–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak-Thompson B, Gould SJ, Loper JE. Identification and sequence analysis of the genes encoding a polyketide synthase required for pyoluteorin biosynthesis in Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Gene. 1997;204:17–24. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00501-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfender WF, Kraus J, Loper JE. A genomic region from Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 required for pyrrolnitrin production and inhibition of Pyrenophora tritici-repentis in wheat straw. Phytopathology. 1993;83:1223–1228. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-83-1223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raaijmakers JM, de Bruijn I, de Kock MJ. Cyclic lipopeptide production by plant-associated Pseudomonas spp.: diversity, activity, biosynthesis, and regulation. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2006;19:699–710. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez F, Pfender WF. Antibiosis and antagonism of Sclerotinia homoeocarpa and Drechslera poae by Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 in vitro and in planta. Phytopathology. 1997;87:614–621. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.6.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi-Tehrani A, Zala M, Natsch A, Moenne-Loccoz Y, Defago G. Biocontrol of soil-borne fungal plant diseases by 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing fluorescent pseudomonads with different restriction profiles of amplified 16S rDNA. Eur J Plant Pathol. 1998;104:631–643. doi: 10.1023/A:1008672104562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allison GE, Angeles D, Tran-Dinh N, Verma NK. Complete genomic sequence of SfV, a serotype-converting temperate bacteriophage of Shigella flexneri. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:1974–1987. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.7.1974-1987.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavrodi DV, Mavrodi OV, McSpadden-Gardener BB, Landa BB, Weller DM, Thomashow LS. Identification of differences in genome content among phlD -positive Pseudomonas fluorescens strains by using PCR-based subtractive hybridization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:5170–5176. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.10.5170-5176.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel-Briand Y, Baysse C. The pyocins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochimie. 2002;84:499–510. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(02)01422-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Takashima K, Ishihara H, Shinomiya T, Kageyama M, Kanaya S, Ohnishi M, Murata T, Mori H, Hayashi T. The R-type pyocin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is related to P2 phage, and the F-type is related to lambda phage. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38:213–231. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R, Wang IN, Roof WD. Phages will out: strategies of host cell lysis. Trends in Microbiology. 2000;8:120–128. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01705-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Retallack DM, Stelman SJ, Hershberger CD, Ramseier T. Characterization of the SOS response of Pseudomonas fluorescens strain DC206 using whole-genome transcript analysis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;269:256–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masure HR, Pearce BJ, Shio H, Spellerberg B. Membrane targeting of RecA during genetic transformation. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:845–852. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodovar N, Vallenet D, Cruveiller S, Rouy Z, Barbe V, Acosta C, Cattolico L, Jubin C, Lajus A, Segurens B, Vacherie B, Wincker P, Weissenbach J, Lemaitre B, Medigue C, Boccard F. Complete genome sequence of the entomopathogenic and metabolically versatile soil bacterium Pseudomonas entomophila. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:673–679. doi: 10.1038/nbt1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buell CR, Joardar V, Lindeberg M, Selengut J, Paulsen IT, Gwinn ML, Dodson RJ, Deboy RT, Durkin AS, Kolonay JF, Madupu R, Daugherty S, Brinkac L, Beanan MJ, Haft DH, Nelson WC, Davidsen T, Zafar N, Zhou L, Liu J, Yuan Q, Khouri H, Fedorova N, Tran B, Russell D, Berry K, Utterback T, van Aken SE, Feldblyum TV, D'Ascenzo M, Deng WL, Ramos AR, Alfano JR, Cartinhour S, Chatterjee AK, Delaney TP, Lazarowitz SG, Martin GB, Schneider DJ, Tang X, Bender CL, White O, Fraser CM, Collmer A. The complete genome sequence of the Arabidopsis and tomato pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10181–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1731982100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson KE, Weinel C, Paulsen IT, Dodson RJ, Hilbert H, Martins dos Santos VA, Fouts DE, Gill SR, Pop M, Holmes M, Brinkac L, Beanan M, DeBoy RT, Daugherty S, Kolonay J, Madupu R, Nelson W, White O, Peterson J, Khouri H, Hance I, Chris Lee P, Holtzapple E, Scanlan D, Tran K, Moazzez A, Utterback T, Rizzo M, Lee K, Kosack D, Moestl D, Wedler H, Lauber J, Stjepandic D, Hoheisel J, Straetz M, Heim S, Kiewitz C, Eisen JA, Timmis KN, Dusterhoft A, Tummler B, Fraser CM. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the metabolically versatile Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ Microbiol. 2002;4:799–808. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyohda A, Furuya N, Ishiwa A, Zhu S, Komano T. Structure and function of the shufflon in plasmid R64. Adv Biophys. 2004;38:183–213. doi: 10.1016/S0065-227X(04)80166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DE, Jeddeloh JA, Fritz DL, DeShazer D. Burkholderia thailandensis E125 harbors a temperate bacteriophage specific for Burkholderia mallei. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:4003–4017. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.14.4003-4017.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker J, Carniel E. Ecological fitness, genomic islands and bacterial pathogenicity. A Darwinian view of the evolution of microbes. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:376–81. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larbig KD, Christmann A, Johann A, Klockgether J, Hartsch T, Merkl R, Wiehlmann L, Fritz HJ, Tummler B. Gene islands integrated into tRNA(Gly) genes confer genome diversity on a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clone. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:6665–80. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.23.6665-6680.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klockgether J, Reva O, Larbig K, Tummler B. Sequence analysis of the mobile genome island pKLC102 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa C. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:518–534. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.2.518-534.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfgang MC, Kulasekara BR, Liang X, Boyd D, Wu K, Yang Q, Miyada CG, Lory S. Conservation of genome content and virulence determinants among clinical and environmental isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8484–8489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832438100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Baldini RL, Deziel E, Saucier M, Zhang Q, Liberati NT, Lee D, Urbach J, Goodman HM, Rahme LG. The broad host range pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 carries two pathogenicity islands harboring plant and animal virulence genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2530–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304622101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitman AR, Jackson RW, Mansfield JW, Kaitell V, Thwaites R, Arnold DL. Exposure to host resistance mechanisms drives evolution of bacterial virulence in plants. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2230–2235. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard M, Vallaeys T, Vorholter FJ, Minoia M, Werlen C, Sentchilo V, Puhler A, Meer JR van der. The clc element of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13, a genomic island with various catabolic properties. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:1999–2013. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.5.1999-2013.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DG, Urbach JM, Wu G, Liberati NT, Feinbaum RL, Miyata S, Diggins LT, He J, Saucier M, Deziel E, Friedman L, Li L, Grills G, Montgomery K, Kucherlapati R, Rahme LG, Ausubel FM. Genomic analysis reveals that Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence is combinatorial. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R90. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-10-r90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil H, Feil WS, Chain P, Larimer F, DiBartolo G, Copeland A, Lykidis A, Trong S, Nolan M, Goltsman E, Thiel J, Malfatti S, Loper JE, Lapidus A, Detter JC, Land M, Richardson PM, Kyrpides NC, Ivanova N, Lindow SE. Comparison of the complete genome sequences of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B728a and pv. tomato DC3000. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11064–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504930102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joardar V, Lindeberg M, Jackson RW, Selengut J, Dodson R, Brinkac LM, Daugherty SC, Deboy R, Durkin AS, Giglio MG, Madupu R, Nelson WC, Rosovitz MJ, Sullivan S, Crabtree J, Creasy T, Davidsen T, Haft DH, Zafar N, Zhou L, Halpin R, Holley T, Khouri H, Feldblyum T, White O, Fraser CM, Chatterjee AK, Cartinhour S, Schneider DJ, Mansfield J, Collmer A, Buell CR. Whole-genome sequence analysis of Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola 1448A reveals divergence among pathovars in genes involved in virulence and transposition. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:6488–98. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.18.6488-6498.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KP. Integration sites for genetic elements in prokaryotic tRNA and tmRNA genes: sublocation preference of integrase subfamilies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:866–875. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.4.866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattoraj DK. Control of plasmid DNA replication by iterons: no longer paradoxical. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:467–476. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Solar G, Giraldo R, Ruiz-Echevarria MJ, Espinosa M, Diaz-Orejas R. Replication and control of circular bacterial plasmids. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:434–464. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.434-464.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith M, Sarov-Blat L, Livneh Z. Plasmid-encoded MucB protein is a DNA polymerase (pol RI) specialized for lesion bypass in the presence of MucA', RecA, and SSB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11227–11231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200361997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Kim SR, Komano T. Twelve pil genes are required for biogenesis of the R64 thin pilus. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2038–2043. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2038-2043.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick JS. Type IV pili and twitching motility. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2002;56:289–314. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komano T. Shufflons: multiple inversion systems and integrons. Annu Rev Genet. 1999;33:171–191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrindt U, Hochhut B, Hentschel U, Hacker J. Genomic islands in pathogenic and environmental microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:414–24. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meer JR van der, Sentchilo V. Genomic islands and the evolution of catabolic pathways in bacteria. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2003;14:248–254. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(03)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohd-Zain Z, Turner SL, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Lilley AK, Inzana TJ, Duncan AJ, Harding RM, Hood DW, Peto TE, Crook DW. Transferable antibiotic resistance elements in Haemophilus influenzae share a common evolutionary origin with a diverse family of syntenic genomic islands. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:8114–8122. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.8114-8122.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joardar V, Lindeberg M, Schneider DJ, Collmer A, Buell CR. Lineage-specific regions in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Mol Plant Pathol. 2005;6:53–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen IT, Press CM, Ravel J, Kobayashi DY, Myers GS, Mavrodi DV, DeBoy RT, Seshadri R, Ren Q, Madupu R, Dodson RJ, Durkin AS, Brinkac LM, Daugherty SC, Sullivan SA, Rosovitz MJ, Gwinn ML, Zhou L, Schneider DJ, Cartinhour SW, Nelson WC, Weidman J, Watkins K, Tran K, Khouri H, Pierson EA, Pierson LS 3rd, Thomashow LS, Loper JE. Complete genome sequence of the plant commensal Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:873–878. doi: 10.1038/nbt1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Frank DW. ExoU is a potent intracellular phospholipase. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:1279–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meer JR van der, Ravatn R, Sentchilo V. The clc element of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 and other mobile degradative elements employing phage-like integrases. Arch Microbiol. 2001;175:79–85. doi: 10.1007/s002030000244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelikani P, Fita I, Loewen PC. Diversity of structures and properties among catalases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:192–208. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3206-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Wallbrunn A, Heipieper HJ, Meinhardt F. Cis/trans isomerisation of unsaturated fatty acids in a cardiolipin synthase knock-out mutant of Pseudomonas putida P8. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;60:179–185. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1080-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama H, Takami H, Inoue A, Horikoshi K. Isolation and characterization of toluene-sensitive mutants from Pseudomonas putida IH-2000. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;169:219–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syn CKC, Magnuson JK, Kingsley MT, Swarup S. Characterization of Pseudomonas putida genes responsive to nutrient limitation. Microbiology. 2004;150:1661–1669. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26657-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romling U, Gomelsky M, Galperin MY. C-di-GMP: the dawning of a novel bacterial signalling system. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:629–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock JB, Ninfa AJ, Stock AM. Protein phosphorylation and regulation of adaptive responses in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:450–490. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.4.450-490.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki H, Tian D, Goss EM, Jakob K, Halldorsdottir SS, Kreitman M, Bergelson J. Presence/absence polymorphism for alternative pathogenicity islands in Pseudomonas viridiflava, a pathogen of Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5887–5892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601431103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfano JR, Charkowski AO, Deng WL, Badel JL, Petnicki-Ocwieja T, van Dijk K, Collmer A. The Pseudomonas syringae Hrp pathogenicity island has a tripartite mosaic structure composed of a cluster of type III secretion genes bounded by exchangeable effector and conserved effector loci that contribute to parasitic fitness and pathogenicity in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4856–4861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canchaya C, Proux C, Fournous G, Bruttin A, Brussow H. Prophage genomics. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:238–276. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.2.238-276.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao EA, Miller SI. Bacteriophages in the evolution of pathogen-host interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9452–9454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel C, Ucurum Z, Michaux P, Adrian M, Haas D. Deleterious impact of a virulent bacteriophage on survival and biocontrol activity of Pseudomonas fluorescens strain CHA0 in natural soil. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2002;15:567–576. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.6.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilley AK, Bailey MJ, Barr M, Kilshaw K, Timms-Wilson TM, Day MJ, Norris SJ, Jones TH, Godfray HC. Population dynamics and gene transfer in genetically modified bacteria in a model microcosm. Mol Ecol. 2003;12:3097–107. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckling A, Rainey PB. The role of parasites in sympatric and allopatric host diversification. Nature. 2002;420:496–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabrane A, Sabri A, Compere P, Jacques P, Vandenberghe I, van Beeumen J, Thonart P. Characterization of serracin P, a phage-tail-like bacteriocin, and its activity against Erwinia amylovora, the fire blight pathogen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:5704–5710. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.11.5704-5710.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boenmare NE, Boyer-Giglio MH, Thaler JO, Akhurst RJ, Brehelin M. Lysogeny and bacteriocinogeny in Xenorhabdus nematophilus and other Xenorhabdus spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3032–3037. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.9.3032-3037.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee HL, Deklerk HC, Coetzee JM, Smit JA. Bacteriophage-tail-like particles associated with intraspecies killing of Proteus vulgaris. J Gen Virol. 1968;2:29–36. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-2-1-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratia JP. Products of defective lysogeny in Serratia marcescens SMG38 and their activity against Escherichia coli other enterobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135(1):23–35. doi: 10.1099/00221287-135-1-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauch E, Kaspar H, Schaudinn C, Dersch P, Madela K, Gewinner C, Hertwig S, Wecke J, Appel B. Characterization of enterocoliticin, a phage tail-like bacteriocin, and its effect on pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:5634–5642. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.12.5634-5642.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill J. Bacteriophage ecology and plants. APSnet Feature. 2003.

- Parret AHA, Temmerman K, De Mot R. Novel lectin-like bacteriocins of biocontrol strain Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:5197–5207. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5197-5207.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada de los Santos P, Parret AHA, De Mot R. Stress-related Pseudomonas genes involved in production of bacteriocin LlpA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;244:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey MJ, Lilley AK, Thompson IP, Rainey PB, Ellis RJ. Site directed chromosomal marking of a fluorescent pseudomonad isolated from the phytosphere of sugar beet. Stability and potential for marker gene transfer. Mol Ecol. 1995;4:755–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.1995.tb00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raaijmakers JM, Weller DM. Natural plant protection by 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas spp. in take-all decline soils. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:144–152. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.2.144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King EO, Ward MK, Raney DE. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescin. J Lab Clin Med. 1954;44:301–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, K S. Short Protocols in Molecular Biology. 5. New York, N. Y.: John Wiley and Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mavrodi OV, Mavrodi DV, Park AA, Weller DM, Thomashow LS. The role of dsbA in colonization of the wheat rhizosphere by Pseudomonas fluorescens Q8r1-96. Microbiology. 2006;152:863–872. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagni M, Ionnidis V, Cerutti L, Zahn-Zabal M, Jongeneel CV, Falquet L. Myhits: a new interactive resource for protein annotation and domain identification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W332–335. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyrlov Bendtsen J, Nieslen H, von Heijne G, S B. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: a Laboratory Manual. 2. Cold Spring Harbor, N. Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Kanaya S, Ohnishi M, Terawaki Y, Hayashi T. The complete nucleotide sequence of phi CTX, a cytotoxin-converting phage of Pseudomonas aeruginosa : implications for phage evolution and horizontal gene transfer via bacteriophages. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:399–419. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover CK, Pham XQ, Erwin AL, Mizoguchi SD, Warrener P, Hickey MJ, Brinkman FS, Hufnagle WO, Kowalik DJ, Lagrou M, Garber RL, Goltry L, Tolentino E, Westbrock-Wadman S, Yuan Y, Brody LL, Coulter SN, Folger KR, Kas A, Larbig K, Lim R, Smith K, Spencer D, Wong GK, Wu Z, Paulsen IT, Reizer J, Saier MH, Hancock RE, Lory S, Olson MV. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature. 2000;406:959–64. doi: 10.1038/35023079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutz EW, Defago G, Kern H. Naturally occurring fluorescent pseudomonads involved in suppression of black root rot of tobacco. Phytopathology. 1986;76:181–185. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-76-181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gardener BBM, Schroeder KL, Kalloger SE, Raaijmakers JM, Thomashow LS, Weller DM. Genotypic and phenotypic diversity of phlD -containing Pseudomonas strains isolated from the rhizosphere of wheat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:1939–1946. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.5.1939-1946.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavrodi OV, Gardener BBM, Mavrodi DV, Bonsall RF, Weller DM, Thomashow LS. Genetic diversity of phlD from 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. Phytopathology. 2001;91:228–228. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2001.91.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa BB, Mavrodi OV, Raaijmakers JM, Gardener BBM, Thomashow LS, Weller DM. Differential ability of genotypes of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens strains to colonize the roots of pea plants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:3226–3237. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.7.3226-3237.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov V, Kiprianova E. Bacteria of Pseudomonas genus. Kiev: Naukova Dumka; 1990. p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan P, O'Sullivan DJ, Simpson P, Glennon JD, O'Gara F. Isolation of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol from a fluorescent pseudomonad and investigation of physiological parameters influencing its production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:353–358. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.1.353-358.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis P, Anjaiah V, Koedam N, Delfosse P, Jacques P, Thonart P, Neirinckx L. Stability, frequency and multiplicity of transposon insertions in the pyoverdine region in the chromosomes of different fluorescent pseudomonads. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1337–1343. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-7-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson IP, Bailey MJ, Fenlon JS, Fermor TR, Lilley AK, Lynch JM, Mccormack PJ, Mcquilken MP, Purdy KJ, Rainey PB, Whipps JM. Quantitative and qualitative seasonal changes in the microbial community from the phyllosphere of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) Plant and Soil. 1993;150:177–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00013015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sequence analysis of prophage 01 of P. fluorescens Pf-5. Table containing annotation of mobile genetic element prophage 01 in the genome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. The following information is provided for each open reading frame: locus tag number, gene name, genome coordinates, length and molecular weight of encoded protein, sequence of putative ribosome binding site, description of the closest GenBank match plus blast E-value, list of functional domains and predicted function.

Sequence analysis of prophage 01 of P. fluorescens Q8r1-96. Table containing annotation of mobile genetic element prophage 01 in the genome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Q8r1-96. The following information is provided for each open reading frame: locus tag number, gene name, genome coordinates, length and molecular weight of encoded protein, sequence of putative ribosome binding site, description of the closest GenBank match plus blast E-value, list of functional domains and predicted function.

Sequence analysis of prophage 03 of P. fluorescens Pf-5. Table containing annotation of mobile genetic element prophage 03 in the genome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. The following information is provided for each open reading frame: locus tag number, gene name, genome coordinates, length and molecular weight of encoded protein, sequence of putative ribosome binding site, description of the closest GenBank match plus blast E-value, list of functional domains and predicted function.