Abstract

Ethanolamine, a product of the breakdown of phosphatidylethanolamine from cell membranes, is abundant in the human intestinal tract and in processed foods. Effective utilization of ethanolamine as a carbon and nitrogen source may provide a survival advantage to bacteria that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract and may influence the virulence of pathogens. In this work, we describe a unique series of posttranscriptional regulatory strategies that influence expression of ethanolamine utilization genes (eut) in Enterococcus, Clostridium, and Listeria species. One of these mechanisms requires an unusual 2-component regulatory system. Regulation involves specific sensing of ethanolamine by a sensor histidine kinase (EutW), resulting in autophosphorylation and subsequent phosphoryl transfer to a response regulator (EutV) containing a RNA-binding domain. Our data suggests that EutV is likely to affect downstream gene expression by interacting with conserved transcription termination signals located within the eut locus. Breakdown of ethanolamine requires adenosylcobalamin (AdoCbl) as a cofactor, and, intriguingly, we also identify an intercistronic AdoCbl riboswitch that has a predicted structure different from previously established AdoCbl riboswitches. We demonstrate that association of AdoCbl to this riboswitch prevents formation of an intrinsic transcription terminator element located within the intercistronic region. Together, these results suggest an intricate and carefully coordinated interplay of multiple regulatory strategies for control of ethanolamine utilization genes. Gene expression appears to be directed by overlapping posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms, each responding to a particular metabolic signal, conceptually akin to regulation by multiple DNA-binding transcription factors.

Keywords: riboswitch, 2-component system

Enterococcus faecalis is a significant pathogen in the hospital environment; however, its most common lifestyle is that of a commensal in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of mammals. In susceptible patients, this commensat relationship can serve as a source of infection (1). Growth under hostile conditions such as the GI tract requires metabolic flexibility, and enterococci can catabolize various energy sources including ethanolamine (2). Ethanolamine is a product of the catabolism of phosphatidylethanolamine, an abundant phospholipid in both mammalian and bacterial membranes (3, 4). Both the host diet and cells within the intestine (bacterial and epithelial) are thought to provide a rich ethanolamine source (5). Correspondingly, several bacterial species found within the GI tract encode the machinery necessary for ethanolamine catabolism, including, but not limited to, E. faecalis, Streptococcus sanguinis, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella, Listeria, and Clostridium species.

For Listeria monocytogenes, the genes of the ethanolamine utilization (eut) locus exhibit increased expression inside the host cell, and loss of one of the key enzymes, EutB, causes a defect in intracellular growth (6). In Salmonella typhimurium, expression of the eut operon is affected by a global regulator of invasion genes (CsrA) (7). In E. faecalis, expression of genes in the eut locus is also influenced by the Fsr global virulence regulatory system (8), and a transposon insertion in this region attenuated killing of Caenorhabditis elegans (9). These data suggest that the ability to use ethanolamine may affect virulence. However, despite a possible role for the eut locus in bacterial pathogenesis, studies of the mechanisms for genetic regulation of these genes are just beginning (10).

Ethanolamine utilization has been best studied in S. typhimurium (11). The catabolism of ethanolamine occurs in a multiprotein complex called the carboxysome, and results in the production of the metabolically useful compound acetyl-CoA (12). The process highly depends on bioavailability of adenosylcobalamin (AdoCbl), because the central enzymatic step requires AdoCbl as a cofactor (13). Expression of these genes in Salmonella is positively regulated by a DNA-binding transcription factor, EutR, encoded within the eut operon and active in the presence of AdoCbl and ethanolamine (5, 14). E. faecalis lacks the EutR regulator, suggesting the existence of alternative regulatory mechanisms for control of ethanolamine catabolism (10).

We describe a unique partnership of multiple posttranscriptional regulatory elements for control of ethanolamine utilization in E. faecalis. One involves a 2-component regulatory system with RNA-binding activity, and the other comprises metabolite-sensing RNA elements, or riboswitches. We postulate that both regulatory systems exert control by influencing the stability of a series of intrinsic transcriptional terminators, as modeled in Fig. 1. Two-component regulatory systems typically include a histidine kinase that autophosphorylates on sensing a specific signal and subsequently transfers the phosphoryl group to a dedicated response regulator. Response regulators typically include a domain for phosphorylation at a conserved aspartate residue and a second domain required for eliciting the regulatory response. The latter most often occurs through protein-DNA or protein–protein interactions (15). However, ≈0.9% of identified eubacterial response regulators (16) contain an ANTAR (AmiR and NasR transcriptional antiterminator regulators) domain (17). The eut-associated response regulator shares this arrangement (10). Two proteins containing ANTAR domains have previously been shown to interact with target mRNA transcripts to prevent formation of a transcription termination signal (16–20). We present evidence that the eut-associated 2-component regulatory system also interfaces with RNA-mediated genetic control strategies. Intriguingly, this system is also retained by other species (e.g., Listeria and Clostridium) that are capable of ethanolamine catabolism, suggesting a common posttranscriptional regulatory circuitry.

Fig. 1.

Model for posttranscriptional control of gene expression in the eut locus of E. faecalis. A subset of genes present in the eut locus of E. faecalis are shown (blue boxes). A classical AdoCbl-sensing riboswitch (blue) is schematically represented upstream of genes predicted to encode for cobalamine transport proteins. A novel, AdoCbl-sensing riboswitch subclass described herein is indicated (red) within the intergenic region upstream of eutG. Conserved hairpins predicted to be transcriptional terminators are shown as green stem-loops. The stability of these terminators is postulated to be affected by the presence of ethanolamine, via the EutWV two-component system, or adenosylcobalamin, via a riboswitch. Posttranscriptional mechanisms predicted to increase downstream expression in response to their metabolic stimulus are indicated by a plus sign, whereas those predicted to decrease expression are indicated with a minus.

In addition to regulation by a 2-component system at the RNA level, we also demonstrate regulation by at least 1 metabolite-sensing riboswitch. Riboswitches are cis-acting regulatory RNA elements located in 5′ untranslated regions (5′-UTR) or intercistronic portions of target mRNAs (21). They consist of 2 domains: a conserved aptamer domain that interacts directly with a specific metabolite, and a variable domain involved in modulating gene expression. Riboswitches responsive to various metabolites have been previously identified. However, the coordinated involvement of protein factors in concert with riboswitch-based mechanisms has not been reported.

Together, these data suggest that multiple posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms are coordinated for regulation of the genes within the eut loci of certain bacterial species. Also, the experiments shown provide support for the hypothesis that bacterial operons can be controlled by multiple posttranscriptional regulatory pathways, each responding to a different input signal, akin to regulation by multiple independent DNA-binding transcription factors.

Results and Discussion

The E. faecalis Genome Contains a Locus Encoding Genes for Ethanolamine Utilization.

Previously, we found that a transposon mutant containing a disruption in one of the ethanolamine utilization genes caused an attenuated phenotype in a C. elegans infection model (9). The gene was originally designated a pduJ homolog (22). However, closer analysis reveals that it is more likely a eutK homolog. We performed BLAST analysis [supporting information (SI) Table S1] of the genes surrounding the transposon insertion, and found many homologs of the S. typhimurium eut genes (11), as did another group in Del Papa and Perego (10). The carboxysome structural genes and essential enzymatic genes have largely been maintained, albeit with some differences. Of particular interest was the absence in E. faecalis of eutR, which encodes for a DNA-binding transcription regulator, and the presence of a 2-component regulatory system originally named HK17 and RR17 (Table S1; see ref. 23). Here, we rename them eutW (histidine kinase), and eutV (response regulator), to conform to nomenclature standards. This observation suggested that EutW/EutV in E. faecalis might replace the regulatory role of EutR in Salmonella.

The EutWV 2-Component System Is Necessary for High-Level Expression of the eut Locus Under Inducing Conditions.

Previous work found that EutV contains a domain consistent with the ANTAR family of proteins (10). The latter consists of a unique class of proteins that have RNA-binding antiterminator function (17). Two response regulators containing this domain have been characterized, AmiR and NasR (18–20). These proteins associate directly with the 5′ UTR of the nascent transcript to prevent formation of an intrinsic terminator. RNA-binding activity of AmiR is activated when it becomes disassociated from its negative regulator AmiC in the presence of free amidates (24). In contrast, RNA-binding activity of NasR is stimulated by direct binding of nitrates to NasR (19). The E. faecalis EutV protein differs from AmiR and NasR in that it contains a classic N-terminal receiver domain, including a conserved phosphoaccepting aspartic acid residue (10).

Because the possible effects of the EutWV 2-component system on eut gene expression has never been examined, we constructed 3 translational fusions to lacZ (Fig. 2A). The region encompassing eutPTG was fused to lacZ to generate eutPTG-lacZ. The intergenic regions upstream of eutP and eutG were also fused to lacZ for eutP-lacZ and eutG-lacZ, respectively. These constructs were transformed into E. faecalis strain OG1RF and assayed in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium. Under these conditions, eutPTG-lacZ and eutP-lacZ exhibited a similar level of expression, whereas no expression was observed for eutG-lacZ or a vector-only control (Fig. 2B). Together, these data suggest that there is likely to be a promoter-active region upstream of eutP, but not eutG.

Fig. 2.

The 2-component system, EutWV, encoded within the eut locus is required for induced expression. (A) Organization of the eut locus in E. faecalis with the inset showing the translational fusions made to lacZ in an E. faecalis shuttle vector. For the predicted functions of the genes, see Table S1. (B) β-galactosidase activity levels observed in wild-type or eutVW E. faecalis strains containing the vectors with the lacZ fusions shown in A.

Previous studies have found that many E. faecalis genes involved in virulence are expressed in serum (25, 26). Because of the possible connections of the operon to pathogenesis, we examined gene expression in BHI medium containing 40% serum. The medium induced expression of the eutPTG-lacZ and eutP-lacZ reporter fusions ≈3-fold above growth in plain BHI (Fig. 2B). To determine whether the EutWV 2-component system affected basal and/or induced expression, the lacZ fusions were assayed for strains containing a deletion of eutVW. Serum-dependent induction of eutPTG-lacZ and eutP-lacZ expression was abrogated in the eutVW background. Instead, low-levels of β-galactosidase activity were maintained under these conditions. The identical results for the eutPTG-lacZ and eutP-lacZ fusions suggested that a EutWV regulatory determinant(s) is likely located upstream of eutP.

Discovery of a Repeated and Conserved RNA Element Within the eut Locus.

Previous work and our own experiments showed that ethanolamine activates autophosphorylation of EutW and phosphorylation of EutV (Fig. S1; ref. 10). Because EutV contains a putative ANTAR output domain, we postulated that phosphoryl transfer between EutW and EutV might be coupled with RNA-binding activity. Also, the observation that the EutWV 2-component regulatory system is conserved between E. faecalis and Listeria and Clostridium species suggested that a common RNA substrate motif could exist.

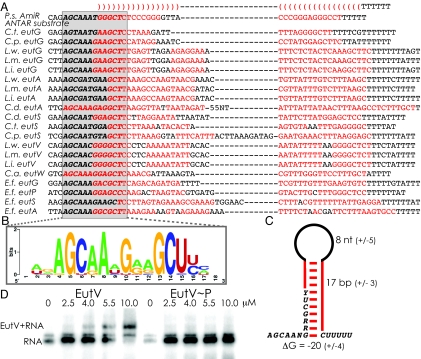

To test this hypothesis, we manually examined intergenic regions larger than 75 nt in the eut locus for bacteria containing EutWV homologs and searched for common features. We identified putative stem-loop elements closely resembling intrinsic transcription terminator hairpins (Figs. 1 and 3). Interestingly, these putative terminator elements were found to share a common 13-nt sequence (AGCAANGRRGCUY) overlapping the 5′-proximal portion (Fig. 3 B and C). Comparative sequence alignments revealed that the primary sequence of the predicted terminator stem-loops varied significantly, whereas the 13-nt sequence exhibited a high degree of conservation.

Fig. 3.

A putative ANTAR recognition motif. (A) Comparative sequence alignment of portions of the intergenic regions upstream of eutG, eutP, eutS, eutV, and eutA from Enterococcus, Listeria, and Clostridium species. A potential base-paired region is shown (red, helical residues) with a conserved primary sequence motif (gray box), which likely constitutes an ANTAR recognition motif. (B) Weblogo representation (38) of the conserved sequence motif. Size of the letter is indicative of frequency of occurrence. (C) A consensus secondary structure model for the base-paired stem and putative ANTAR recognition motif. (D) An electrophoretic mobility shift assay using γ-32P-radiolabeled RNA that encompasses the eutP 5′ UTR demonstrates an interaction of the RNA with unphosphorylated (Left), but not phosphorylated (Right) EutV.

Remarkably, the portion of the 5′ UTR of the amidase operon that is required for association with AmiR shared the consensus pattern for the eut-associated terminator motif (Fig. 3A). The fact that sequence and structural motifs in the eut loci closely resemble an established RNA substrate of an ANTAR regulatory protein suggests strongly that they are likely EutWV regulatory targets. We identified the conserved element primarily upstream of a subset of the eutG, eutS, eutA, and eutV genes for each of the relevant species (Figs. 1 and 3A). It could be clearly identified upstream of eutP, eutG, eutS, and eutA in E. faecalis. These observations suggest multiple points of posttranscriptional regulatory control by EutWV within the eut loci. Interestingly, recent data has suggested that a region encompassing the eutS upstream sequence was induced in the presence of ethanolamine (10). Our work suggests that the region upstream of eutP is required for activation by EutWV (Fig. 2). Both observations agree well with identification of the terminator element upstream of the eutS and eutP genes, and are consistent with a regulatory role. Because our analysis was limited to eut operons, it is possible that the conserved sequence element may be present elsewhere in the genome as part of a broader regulon.

The simplest interpretation of these data are that ethanolamine triggers phosphorylation of EutV, which in turn activates association with the eut-associated terminator motif, stimulating antitermination and synthesis of the ethanolamine catabolism genes. To test this hypothesis, EutW and EutV were cloned into expression vectors that added N-terminal hexahistidine tags, and the proteins were overproduced in E. coli and purified from cell lysates by using affinity chromatography. After verifying that autophosphorylation of EutW and phosphorylation EutV occurs in an ethanolamine-dependent manner (Fig. S1; ref. 10), we purified phosphorylated and unphosphorylated protein. Preliminary tests of RNA-binding activity suggest that, indeed, there is a physical relationship between EutV and the eut-associated RNA motif (Fig. 3D). However, in contrast to our expectations, unphosphorylated EutV may exhibit improved affinity for the RNA substrate, rather than phosphorylated EutV. Also, preliminary tests of RNA-binding activity of EutW suggest that it also may exhibit RNA-binding activity. Therefore, the molecular details of the relationship between EutV and EutW and the conserved RNA element require further elucidation.

AdoCbl-Sensing Riboswitches Are Found Within the eut Locus.

In Salmonella, expression of ethanolamine catabolism genes is controlled by the EutR transcription factor, which responds to both ethanolamine and AdoCbl to drive transcription. Sensitivity to AdoCbl is logical, because it is required for the main enzymatic step in ethanolamine catabolism (13). Therefore, it would not be unexpected for other microorganisms to regulate ethanolamine catabolism in a manner sensitive to the presence of AdoCbl. Indeed, growth on ethanolamine as the sole carbon source in E. faecalis requires AdoCbl (10). Sensitivity of the EutWV 2-component regulatory system to ethanolamine, as published previously (10) and here (Fig. S1), suggests a basis for ethanolamine-responsive regulation of the eut locus. However, our studies also reveal a regulatory mechanism for sensing AdoCbl.

Because riboswitches that sense AdoCbl have previously been described, we manually examined intergenic regions within the eut locus for evidence of secondary structure and primary sequence conservation. These regions were also analyzed by using the RNA motif search program, Ribex (27). These efforts resulted in the identification of a putative regulatory RNA located between eutT and eutG (Figs. 1 and 3B). Notably, this RNA element exhibited partial similarity to an adenosylcobalmin-sensing riboswitch class described previously (Fig. 3B; refs. 14, 28–31). However, only a portion of the canonical AdoCbl-sensing riboswitch could be initially recognized, suggesting that the E. faecalis eutT-G RNA element may be significantly different. Indeed, this putative RNA element was not identified by prior bioinformatics-based searches for AdoCbl-sensing riboswitches (28, 29, 31). Closer inspection of the eutT-G intergenic region yielded 2 key observations. First, a sequence motif closely resembling the E. faecalis eutT-G element could also be identified within the eut operon of Listeria species, suggesting conservation of this element. Comparative sequence alignment of the eutT-G intergenic region for Listeria and Enterococcus species revealed many individual nucleotide differences between them (Fig. 4B and Fig. S2). However, many of the changes are such that base-pairing potential is maintained, in support of the postulated secondary structural arrangement. Also, the eut T–G element appeared to contain many of the structural and sequence features of the minimal core region (32) of AdoCbl-sensing riboswitches (Fig. 4B and Fig. S2), suggesting a functional relationship. However, the eutT-G RNA element contains important differences. Specifically, canonical AdoCbl riboswitches include a paired region (P1) formed from the 5′ and 3′ terminal nucleotides. In contrast, the eutT-G RNA element lacks both this and a neighboring helical element (P2). Also, the eutT-G RNA element appears to contain an extra base-paired region near the 3′ terminus that is absent from the canonical AdoCbl riboswitch. Based on these observations, we hypothesized that the eutT-G RNA element constitutes a subclass of the previously described AdoCbl riboswitch. Interestingly, although previous bioinformatics techniques were unable to identify the eutT-G element, they were able to identify an additional, canonical AdoCbl riboswitch (28, 31), immediately upstream of the eut locus, located in the promoter region of an operon predicted to encode for cobalamin transport (Fig. 1).

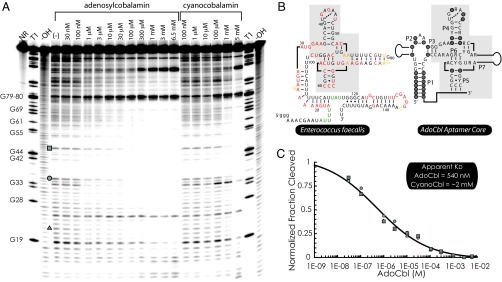

Fig. 4.

AdoCbl induces structural changes within the eutG 5′ UTR. (A) Representative in-line probing data for the E. faecalis eutG riboswitch region with increasing concentrations of AdoCbl and cyanocobalamin. Controls include nonreacted RNA (NR), partial digestion by RNase T1 (cleavage at G residues) and partial alkaline digestion (cleavage at all residues). Shaded symbols mark bands used for quantitative analyses. (B) Proposed secondary structure model for the E. faecalis eutT-G riboswitch showing nucleotides that are more constrained (red), less constrained (green), or unaffected (yellow) on addition of AdoCbl. Also shown is the consensus secondary structure model of the classical AdoCbl-sensing riboswitch. The gray box highlights the conserved core region (32). (C) Normalized fraction cleaved plotted against AdoCbl concentration is shown for the residues indicated in A. The gray line results from a 4-parameter logistic fit of the data. The results of the nonlinear regression analysis suggest a binding affinity of 540 nM for AdoCbl, and >2 mM for cyanocobalamin.

To test for riboswitch function, the eutT-G intergenic region was synthesized in vitro and subjected to in-line probing, a sequence-independent method of qualitatively assessing changes in RNA secondary structure (33, 34). In-line probing of the entire eutT-G intergenic region (>400 nt) indicated that only a portion of the overall region appeared to exhibit a significant degree of secondary structure content. Further truncations of the transcript narrowed this region to ≈200 nt that include the putative riboswitch. Then, in-line probing was used to investigate changes in the eutT-G riboswitch secondary structure arrangement on addition of varying concentrations of AdoCbl. Addition of AdoCbl resulted in decreased band intensity at many different RNA positions (Fig. 4A), suggesting that AdoCbl promoted stabilization of an array of secondary structure features that agree well with our model (Fig. 4B). Each of the positions exhibiting a change in band intensity responded similarly to AdoCbl, suggesting a concerted change in RNA structure. In total, these data suggest that AdoCbl induces a global conformational change for the eutT-G riboswitch with an apparent Kd of ≈540 nM (Fig. 4C), comparable with disassociation constants for the canonical AdoCbl riboswitch (30). In contrast, the apparent Kd for an analog, cyanocobalamin, was substantially poorer, demonstrating selectivity for AdoCbl.

Association of AdoCbl with the eutT-G Riboswitch Induces Transcription Antitermination.

In general, riboswitches regulate gene expression by exerting control over transcription termination, translation initiation, or mRNA stability (21). Typically, riboswitches in Gram-positive bacteria control formation of an intrinsic transcription terminator in response to a metabolite. Consistent with this expectation, putative transcription terminator helices could be identified immediately downstream of both the canonical AdoCbl riboswitch and the eutT-G AdoCbl riboswitch subclass (Figs. 1 and 3A). Therefore, we investigated whether AdoCbl changes transcription termination in the eutT-G intergenic region.

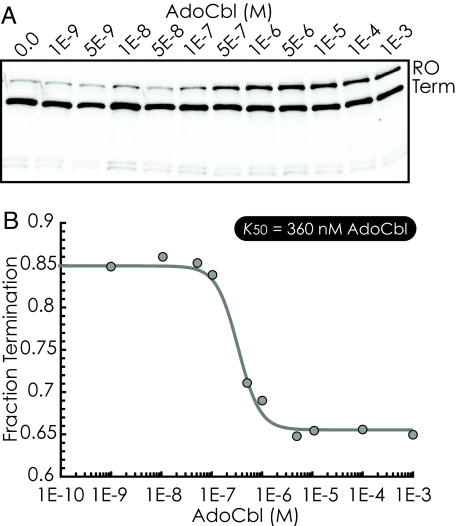

Measurements of transcription in vitro for DNA templates encompassing the entire eutT-G region resulted in 2 primary transcripts (Fig. 5A), which correlated to the expected sizes of a runoff and a terminated transcript. The majority (85%) of the products corresponded to the terminated transcript. However, this fraction decreased on addition of AdoCbl, reaching a minimum of 65% termination. Half-maximal decrease in termination was achieved with 370 nM AdoCbl (Fig. 5B). These data reveal that association of AdoCbl with the eutT-G riboswitch inhibits termination, thus, promoting synthesis of the downstream genes. This result is in contrast to previously characterized AdoCbl-sensing riboswitches, which, in concordance with their function in feedback inhibition of cobalamin biosynthesis or import, promote termination in response to AdoCbl (29, 31).

Fig. 5.

AdoCbl induces antitermination in vitro. (A) In vitro transcription analysis of the eutG 5′ UTR with varying concentrations of AdoCbl. Each individual reaction resulted in transcripts corresponding to premature termination (Lower) and runoff transcription of the DNA template (Upper). (B) The fraction of transcripts resulting from premature transcription termination is shown plotted against [AdoCbl]. The half-maximal change in the fraction termination corresponded to 350 nM AdoCbl.

Interestingly, close inspection of the eutT-G terminator helix revealed that it contains the conserved sequence found in the other eut terminator elements that we have proposed as substrates for the EutWV 2-component signaling pathway (Fig. 3A). This observation raises the intriguing hypothesis that 2 separate posttranscriptional regulatory pathways, the AdoCbl riboswitch and EutWV-mediated antitermination, both exert regulatory control over the same intrinsic terminator helix (Fig. 1). It remains to be determined whether these posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms function independently or in concert to influence terminator formation.

Conclusions

Many individual DNA-binding transcription factors that function as repressors or activators have been identified in bacteria. Also, it has been established that bacterial operons are oftentimes subjected to regulatory control by combinations of transcription factors (35). Thus, the use of multiple transcription factors, functioning either independently or via hierarchical relationships, allows for control of gene expression in response to combinatorial input signals. However, in the past decade it has become increasingly apparent that posttranscriptional regulatory circuitry is also fundamentally important for bacterial gene regulation. There are many different types of RNA-mediated regulatory mechanisms that have been described, including regulatory RNAs that function in trans, relative to their target transcripts, and those functioning in cis. Of the latter, almost all published examples are located in the 5′-untranslated region or within intergenic regions of polycistronic transcripts. Typically, one particular class of cis-acting regulatory RNA is associated with a given operon, akin to regulation by a single, signal-responsive transcription factor. However, we have found that multiple posttranscriptional regulatory strategies converge for regulation of ethanolamine catabolism in Enterococcus, Clostridium, and Listeria species. The coupling of different RNA-mediated control mechanisms allows for coordinated regulation in response to 2 separate metabolic stimuli, ethanolamine and AdoCbl (Fig. 1). Therefore, these data suggest that bacterial operons may be subjected to overlapping and independent RNA-mediated regulatory circuitry, conceptually similar to the use of multiple transcription factors.

Materials and Methods

A brief overview is provided here. For greater detail, see SI Methods and Table S2.

β-Galactosidase Assays.

OG1RF was the E. faecalis strain background used in our studies. Strains containing constructs described in Fig. 1A were cultured overnight in BHI medium. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:50 in fresh BHI medium or BHI with 40% horse serum (BHIS), and grown at 37 °C for 4 h, collected, and β-Galactosidase assays carried out as previously described (36).

EutV and EutW Biochemical Assays.

Strains capable of producing N-terminal His6-tagged EutW and EutV were created and induced. The cells were disrupted and the proteins affinity purified by use of a Cobalt TALON resin (Clontech). Purity of EutV and EutW was >90%, as judged by 10% SDS/PAGE followed by Coomassie-staining. To examine phosphorylation, EutW and/or EutV were incubated in buffer containing γ-32P ATP and specified concentrations of ethanolamine for 30 min at 25 °C. The samples were resolved by 10% SDS/PAGE on 2 gels, one stained with Coomassie Brilliant blue and the other visualized by using a PhosphorImager (Amersham). To examine the ability of eutV to bind the untranslated 5′ region of eutP, this region was synthesized in vitro and radiolabeled with γ-32P ATP. The RNA was incubated with specified concentrations of unphosphorylated or phosphorylated EutV in the presence of 2.5 mM MgCl2 for 60 min at 25 °C, and resolved by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis.

In-Line Probing Reactions and Transcription Termination Assays.

The E. faecalis eutT-G intergenic region was amplified, and RNAs synthesized by T7 RNAP and 5′-radiolabeled with γ-32P ATP as described previously (37). After incubation in reaction buffer at 25 °C for ≈40 h, the products were resolved by 10% PAGE. The same region was amplified for transcription termination assays and the reactions performed as described previously by using E. coli RNA polymerase (37).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank A. Van Hoof for valuable advice, and A. Maadani and P. Buzombo for excellent technical assistance. D.A.G. was supported by a New Scholar Award in Global Infectious Disease from the Ellison Medical Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health Grant R21AI078104. W.C.W. was supported by the Welch Foundation Grant I-1643 and the National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM081882. A.B. was supported by R37 AI 47923 to B.E. Murray.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0812194106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Malani PN, Kauffman CA, Zervos MJ. In: The Enterococci, Pathogenesis, Molecular Biology, and Antibiotic Resistance. Gilmore MS, editor. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huycke MM. In: The Enterococci, Pathogenesis, Molecular Biology and Antibiotic Resistance. Gilmore MS, editor. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology Press; 2002. pp. 301–354. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randle CL, Albro PW, Dittmer JC. The phosphoglyceride composition of Gram-negative bacteria and the changes in composition during growth. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;187:214–220. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(69)90030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White DA. In: Form and function of phospholipids. Ansell GB, Hawthorne JN, Dawson RMC, editors. New York: Elsevier Publishing Company; 1973. pp. 441–482. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roof DM, Roth JR. Ethanolamine utilization in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3855–3863. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.3855-3863.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joseph B, et al. Identification of Listeria monocytogenes genes contributing to intracellular replication by expression profiling and mutant screening. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:556–568. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.556-568.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawhon SD, et al. Global regulation by CsrA in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1633–1645. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourgogne A, Hilsenbeck SG, Dunny GM, Murray BE. Comparison of OG1RF and an isogenic fsrB deletion mutant by transcriptional analysis: The Fsr system of Enterococcus faecalis is more than the activator of gelatinase and serine protease. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:2875–2884. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.8.2875-2884.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maadani A, Fox KA, Mylonakis E, Garsin DA. Enterococcus faecalis Mutations Affecting Virulence in the C. elegans Model Host. Infect Immun. 2007;75:2634–2637. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01372-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Del Papa MF, Perego M. Ethanolamine activates a sensor histidine kinase regulating its utilization in Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 2008;12:7147–7156. doi: 10.1128/JB.00952-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brinsmade SR, Paldon T, Escalante-Semerena JC. Minimal functions and physiological conditions required for growth of salmonella enterica on ethanolamine in the absence of the metabolosome. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:8039–8046. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.23.8039-8046.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kofoid E, Rappleye C, Stojiljkovic I, Roth J. The 17-gene ethanolamine (eut) operon of Salmonella typhimurium encodes five homologues of carboxysome shell proteins. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5317–5329. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5317-5329.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scarlett FA, Turner JM. Microbial metabolism of amino alcohols. Ethanolamine catabolism mediated by coenzyme B12-dependent ethanolamine ammonia-lyase in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella aerogenes. J Gen Microbiol. 1976;95:173–176. doi: 10.1099/00221287-95-1-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roof DM, Roth JR. Autogenous regulation of ethanolamine utilization by a transcriptional activator of the eut operon in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6634–6643. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6634-6643.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laub MT, Goulian M. Specificity in two-component signal transduction pathways. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:121–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.042007.170548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galperin MY. Structural classification of bacterial response regulators: Diversity of output domains and domain combinations. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:4169–4182. doi: 10.1128/JB.01887-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shu CJ, Zhulin IB. ANTAR: An RNA-binding domain in transcription antitermination regulatory proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:3–5. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)02036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chai W, Stewart V. NasR, a novel RNA-binding protein, mediates nitrate-responsive transcription antitermination of the Klebsiella oxytoca M5al nasF operon leader in vitro. J Mol Biol. 1998;283:339–351. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chai W, Stewart V. RNA sequence requirements for NasR-mediated, nitrate-responsive transcription antitermination of the Klebsiella oxytoca M5al nasF operon leader. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:203–216. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson SA, Wachira SJ, Norman RA, Pearl LH, Drew RE. Transcription antitermination regulation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa amidase operon. EMBO J. 1996;15:5907–5916. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winkler WC, Breaker RR. Regulation of bacterial gene expression by riboswitches. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:487–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paulsen IT, et al. Role of mobile DNA in the evolution of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Science. 2003;299:2071–2074. doi: 10.1126/science.1080613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hancock LE, Perego M. Systematic inactivation and phenotypic characterization of two-component signal transduction systems of Enterococcus faecalis V583. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7951–7958. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.7951-7958.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norman RA, Poh CL, Pearl LH, O'Hara BP, Drew RE. Steric hindrance regulation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa amidase operon. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30660–30667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000813200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nallapareddy SR, Qin X, Weinstock GM, Hook M, Murray BE. Enterococcus faecalis adhesin, ace, mediates attachment to extracellular matrix proteins collagen type IV and laminin as well as collagen type I. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5218–5224. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.5218-5224.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shepard BD, Gilmore MS. Differential expression of virulence-related genes in Enterococcus faecalis in response to biological cues in serum and urine. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4344–4352. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4344-4352.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abreu-Goodger C, Merino E. RibEx: A web server for locating riboswitches and other conserved bacterial regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W690–W692. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gardner PP, et al. Rfam: Updates to the RNA families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D136–D140. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nahvi A, Barrick JE, Breaker RR. Coenzyme B12 riboswitches are widespread genetic control elements in prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:143–150. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nahvi A, et al. Genetic control by a metabolite binding mRNA. Chem Biol. 2002;9:1043. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vitreschak AG, Rodionov DA, Mironov AA, Gelfand MS. Regulation of the vitamin B12 metabolism and transport in bacteria by a conserved RNA structural element. RNA. 2003;9:1084–1097. doi: 10.1261/rna.5710303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrick JE, Breaker RR. The distributions, mechanisms, and structures of metabolite-binding riboswitches. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R239. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soukup GA, Breaker RR. Relationship between internucleotide linkage geometry and the stability of RNA. RNA. 1999;5:1308–1325. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winkler W, Nahvi A, Breaker RR. Thiamine derivatives bind messenger RNAs directly to regulate bacterial gene expression. Nature. 2002;419:952–956. doi: 10.1038/nature01145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Browning DF, Busby SJ. The regulation of bacterial transcription initiation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:57–65. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller DM, III, et al. Two-color GFP expression system for C. elegans. Biotechniques. 1999;8:920–921. doi: 10.2144/99265rr01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dann CE, III, et al. Structure and mechanism of a metal-sensing regulatory RNA. Cell. 2007;130:878–892. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.