Abstract

Salmonella pathogenesis relies upon the delivery of over thirty specialised effector proteins into the host cell via two distinct type III secretion systems. These effectors act in concert to subvert the host cell cytoskeleton, signal transduction pathways, membrane trafficking and pro-inflammatory responses. This allows Salmonella to invade non-phagocytic epithelial cells, establish and maintain an intracellular replicative niche and, in some cases, disseminate to cause systemic disease. This review focuses on the actions of the effectors on their host cell targets during each stage of Salmonella infection.

Introduction

Salmonellae are enteropathogenic Gram-negative bacteria that infect humans and animals, causing each year ∼1.3 billion cases of human disease ranging from diarrhoea to systemic typhoid fever. Following ingestion by the host, Salmonella invades the intestinal mucosa via several routes. Bacteria may be taken up by antigen-sampling M cells, be captured in the lumen by CD18-expressing phagocytes that penetrate the epithelial monolayer, or may force their own entry into non-phagocytic enterocytes. Upon internalisation into non-phagocytic cells, Salmonella becomes enclosed within an intracellular phagosomal compartment termed the Salmonella-containing vacuole (SCV). The maturing SCV traffics towards the Golgi apparatus, undergoing selective interactions with the host endocytic pathway. Once positioned within the perinuclear area, the SCV-enclosed bacteria replicate, a stage characterised by formation of tubulovesicular SCV structures called Salmonella-induced filaments (Sifs). Although most Salmonella infections remain localised to the intestine, where stimulation of inflammatory responses contributes to diarrhoea, in typhoid disease Salmonella survives in intestinal macrophages, disseminating to the liver and spleen via the bloodstream and lymphatic system (Figure 1). This multi stage infection of the host is directed by Salmonella-mediated delivery of an array of specialised effector proteins into the eukaryotic host cells via two distinct type III secretion systems (T3SSs), encoded by pathogenicity islands 1 (SPI-1 T3SS) and 2 (SPI-2 T3SS). Additional secretion systems, including the sci-encoded (Salmonella enterica centisome 7 genomic island) type VI secretion system [1] and the ZirTS pathway [2], appear to be functional during Salmonella infection and have been demonstrated to contribute towards virulence. However, these systems are not currently well characterised compared to the SPI-1 and SPI-2 T3SSs.

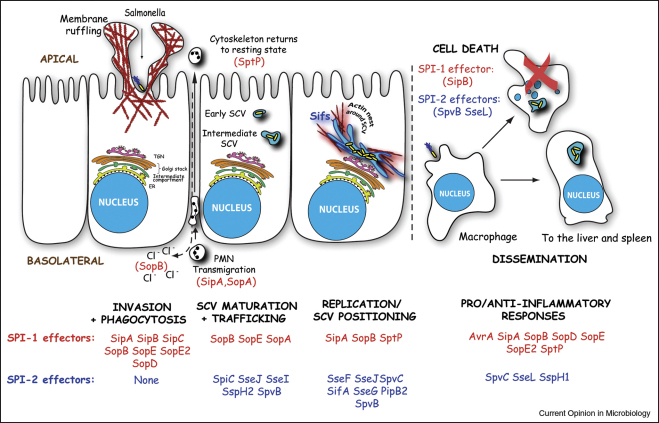

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the major stages underlying Salmonella infection. Salmonellae invade non-phagocytic cells by inducing membrane deformation and rearrangement of the underlying actin cytoskeleton (membrane ruffling), enclosing bacteria in intracellular phagosomal compartments termed Salmonella-containing vacuoles (SCVs). SCVs traffic towards the perinuclear region of the host cell and mature via selective interactions with the endocytic pathway. Once the SCV is positioned next to the Golgi apparatus, intracellular bacterial replication begins. This stage is characterised by the formation of SCV tubulovesicular structures called Salmonella-induced filaments (Sifs) and the accumulation of F-actin around the bacterial phagosome (actin nest). Chloride ion (Cl-) secretion and polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) transmigration contribute towards diarrhoea and intestinal inflammation. In addition, Salmonella manipulates specific host immune response pathways. Salmonella serovars associated with systemic disease are able to enter intestinal macrophages, inducing cell death as well as using them as a vehicle to disseminate to the liver and spleen via the bloodstream and lymphatic system. SPI-1 and SPI-2 effectors involved in each individual infection stage are indicated. Note that SPI-1 and SPI-2 effectors do not operate sequentially and independently of one another as previously thought. Instead, both subsets play key roles in SCV maturation, positioning and replication (Abbreviations: ER, endoplasmic reticulum; TGN, trans-Golgi network).

Over thirty SPI-1 and SPI-2 T3SS effectors have been shown to manipulate a succession of key host cellular functions, including signal transduction, membrane trafficking and pro-inflammatory immune responses (Tables 1 and 2, see Supplementary information for fully referenced versions). In this review, we will summarise the actions of these effectors on their host cell targets and indicate emerging examples of effector cooperation.

Table 1.

Effectors requiring the SPI-1-encoded T3SS for their translocation.

| Effector | Gene location | Selected homologues | Activity | Host cell target(s) | Role in infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AvrA | SPI-1 | Yersinia YopJ/P | Cysteine protease with deubiquitinase activity, acetyltransferase | MKK4/7, IκBα, β-catenin | Inhibits inflammation, represses apoptosis & epithelial innate immunity |

| SipA (SspA) | SPI-1 | Shigella IpaA | Actin binding/stabilising | Actin, T-plastin | Increases internalisation efficiency, enhances actin assembly, potentiates SipC activity, triggers PMN transmigration, maintains perinuclear SCV positioning, disrupts tight junctions |

| SipB (SspB) | SPI-1 | Shigella IpaB | SPI-1 TTSS translocon component | Cholesterol | SPI-1 effector delivery, apoptosis of phagocytes |

| SipC (SspC) | SPI-1 | Shigella IpaC | SPI-1 TTSS translocon component, actin nucleation & bundling | Actin | SPI-1 effector delivery, induces membrane ruffling |

| SipD (SspD) | SPI-1 | Shigella IpaD | Regulates SPI-1 effector secretion | ||

| SopA | Outside SPI-1 | Putative EHEC effector (Genbank NP_309587.1) | E3 ubiquitin ligase | HsRMA1 | Disrupts SCV integrity, induces PMN transmigration |

| SopB (SigD) | SPI-5 | Shigella spp. IpgD, cellular 4-phosphatases, synaptojanin | Inositol polyphosphate phosphatase | Inositol phosphates | Promotes membrane fission & macropinosome formation, maintains perinuclear SCV positioning, promotes epithelial cell survival, triggers nitric oxide production in macrophages, promotes fluid secretion, disrupts tight junctions |

| SopE | Bacteriophage SopEϕ | Salmonella SopE2 | Guanine exchange factor (GEF) mimic | Rac-1, Cdc42 | Induces membrane ruffling & proinflammatory responses, promotes fusion of SCV with early endosomes, disrupts tight junctions |

| SopE2 | In vicinity of bacteriophage remnants | Salmonella SopE | GEF mimic | Cdc42 | Induces membrane ruffling & proinflammatory responses, increases macrophage iNos expression, disrupts tight junctions |

| SptP | SPI-1 | N-terminus: Yersinia YopE, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoS. C-terminus: cellular tyrosine phosphatases, Yersinia YopH | GTPase activating protein (GAP) mimic, tyrosine phosphatase | Cdc42, Rac-1, vimentin | Returns host cytoskeleton to resting state following bacterial entry, downregulates proinflammatory responses |

| SlrPa | Outside SPI-1/SPI-2 | Salmonella SspH1/H2, GogB, Yersinia YopM, Shigella IpaH7.8/9.8 | Ubiquitin ligase? | Confers host specificity? | |

| SopDa | Outside SPI-1/SPI-2 | Salmonella SopD2 | Promotes membrane fission & macropinosome formation, contributes to Salmonella virulence and persistence in mice, induces fluid secretion, promotes invasion of T84 cells | ||

| SspH1a | Bacteriophage Gifsy-3 | Salmonella SspH2, SlrP, GogB, Yersinia YopM, Shigella IpaH7.8/9.8 | E3 ubiquitin ligase | PKN1 | Downregulates proinflammatory responses |

| SteA (STM1583)a | Outside SPI-2 | Required for efficient mouse spleen colonisation | |||

| SteB (STM1629)a | Outside SPI-2 | Putative picolinate reductase |

Can also be translocated via the SPI-2-encoded T3SS.

Table 2.

Effectors requiring the SPI-2-encoded T3SS for their translocation.

| Effector | Gene location | Selected homologues | Activity | Host cell target(s) | Role in infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GogB | Bacteriophage Gifsy-1 | N-terminus: Yersinia YopM, Shigella IpaH7.8/9.8, Salmonella SspH1/2, SlrP. C-terminus: Yersinia YP2634/Y1471, rabbit EPEC OrfL, EHEC 0157:H7 Z1829 | |||

| PipB | SPI-5 | Salmonella PipB2 | |||

| PipB2 | Outside SPI-2 | Salmonella PipB | Kinesin-1 | Promotes Sif extension, recruits kinesin-1 to SCV | |

| SifA | Outside SPI-2 | Salmonella SifB | Rab mimic? | SKIP, Rab7/9 | Required for SCV membrane integrity & Sif formation, maintains perinuclear SCV positioning, redirects exocytic vesicles to SCV |

| SifB | Outside SPI-2 | Salmonella SifA | |||

| SopD2 | Outside SPI-2 | Salmonella SopD | Contributes to Sif formation, required for efficient bacterial replication in macrophages & mice | ||

| SpiC (SsaB) | SPI-2 | Hook 3, TassC | Interferes with vesicular trafficking, role in SCV-associated actin polymerisation (VAP) and Sif formation, controls order of protein export through SPI-2 T3SS | ||

| SseF | SPI-2 | Contributes to Sif formation, recruits dynein to SCV, maintains perinuclear SCV positioning, required for formation of microtubule bundles around SCV, redirects exocytic transport vesicles to SCV | |||

| SseG | SPI-2 | As SseF | |||

| SseI (SrfH/GtgB) | Bacteriophage Gifsy-2 | Filamin, TRIP6 | Remodels SCV associated F-actin? Promotes phagocyte motility | ||

| SseJ | Outside SPI-2 | Deacylase, phospholipase A & glycerol-phospholipid :cholesterol acyltransferase | Cholesterol | Negative regulation of Sifs, antagonises SifA SCV stabilisation | |

| SseK1 | Outside SPI-2 | Salmonella SseK2/3, Citrobacter rodentium NleB, EHEC Z4328 | |||

| SseK2 | Outside SPI-2 | Salmonella SseK1/3, Citrobacter rodentium NleB, EHEC Z4328 | |||

| SseK3 (NleB)a | ST64B coliform bacteriophage | Salmonella SseK1/2, Citrobacter rodentium NleB, EHEC Z4328 | |||

| SseL | Outside SPI-2 | Cysteine protease with deubiquitinase activity | IκBα | Macrophage apoptosis, downregulates inflammatory responses | |

| SspH2 | In vicinity of bacteriophage remnants | Salmonella SspH1, SlrP, GogB, Yersinia YopM, Shigella IpaH7.8/9.8 | Inhibits actin polymerisation in vitro | Filamin, Profilin | Remodels SCV associated F actin? |

| SteC (STM1698) | Outside SPI-2 | Eukaryotic kinases | Serine/Threonine kinase | Required for VAP | |

| SpvBb | pSLT (S. typhimurium) | N-terminus: Photorhabdus luminescens TcaC. N-terminus: Bacillus cereus VipB2, Clostridium botulinum C2 toxin component 1/C3 toxin, Clostridium perfringens Iota | ADP ribosyl transferase, inhibits actin polymerisation in vitro, depolymerises F-actin upon transfection | Actin | Inhibition of VAP, apoptosis of infected cells, required for full virulence in mice |

| SpvCb | pSLT (S. typhimurium) | Shigella OspF, Pseudomonas syringae HopAI1 | Phosphothreonine lyase | Required for full virulence in mice |

Found in S. typhimurium SL1344, not LT2.

Found in non-typhoid Salmonella serovars.

Effector-mediated forced entry into non-phagocytic epithelial cells

A subset of delivered SPI-1 effectors (SipA, SipC, SopB, SopD, SopE, SopE2) function to induce membrane deformation and rearrangement of the underlying actin cytoskeleton (‘membrane ruffling’), triggering bacterial internalisation into SCVs.

The C-terminus of the SPI-1 T3SS translocon component SipC (SspC) directly nucleates actin assembly leading to rapid filament growth from barbed ends, whereas its N-terminus bundles actin filaments [3]. Although not necessary for Salmonella entry, SipA (SspA) increases invasion efficiency into cultured cells [3] and enhances Salmonella enterocolitis in vivo [4]. SipA promotes actin polymerisation by reducing the critical concentration for actin assembly [3] and binds to F-actin with high affinity, resulting in mechanical stabilisation of filaments [3,5,6]. SipA potentiates the actin nucleating and bundling activities of SipC [3] and enhances the activity of the host actin bundling protein T-plastin (fimbrin) [3,6]. SipA also prevents binding of the cellular actin depolymerising proteins ADF/cofilin to F-actin and displaces pre-bound ADF/cofilin from F-actin [5]. The F-actin severing activity of cellular gelsolin was originally reported to be prevented by SipA [5], but a later study showed that higher concentrations of gelsolin were able to partially sever SipA-F-actin complexes [7]. In addition, SipA is able to reanneal gelsolin-severed and -capped actin filament fragments [5,7].

In contrast to SipA and SipC, SopE and SopE2 do not bind actin. They modulate the host actin cytoskeleton indirectly by mimicking cellular guanine exchange factors (GEFs) [6]. In particular, they catalyse the exchange of bound GDP for GTP to activate host Rho GTPases that stimulate downstream pathways that drive actin cytoskeletal assembly via Arp2/3. In vitro, SopE and SopE2 have differing substrate specificities; while SopE activates Rac-1 and Cdc42, SopE2 appears to exhibit specificity for Cdc42 [6]. SopE-dependent activation of Rac-1 alone appears sufficient for bacterial internalisation [8•].

The inositol phosphatase SopB (SigD) dephosphorylates a range of phosphoinositide phosphate and inositol phosphate substrates in vitro [4,6]. Inhibition of SopB phosphoinositide phosphatase activity attenuates Salmonella-induced cytoskeletal reorganisation [6]. Recent work indicates that SopB-dependent stimulation of the cellular SH3-containing guanine nucleotide exchange factor, SGEF, activates the small GTPase RhoG, which contributes to the actin remodelling that occurs during Salmonella entry [8•].

SopB-dependent hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2 at the ruffling host membrane enhances the subsequent annealing of plasmalemmal invaginations to rapidly enclose bacteria within a sealed phagosome (the SCV) [6]. In addition, SopB-dependent formation of PI(3)P at the host plasma membrane has been reported to contribute towards the formation of larger, more stable macropinosomes [6] and has been shown to facilitate bacterial phagocytosis by recruiting the host SNARE protein VAMP8 [9]. Another effector, SopD, cooperates with SopB to aid membrane fission and macropinosome formation [10].

Following engulfment Salmonellae return the host cell cytoskeleton back to its resting state, an event mediated by the N-terminal GTPase activation (GAP) domain of SptP. This stimulates the intrinsic GTPase activities of SopE/SopE2/SopB-activated Cdc42 and Rac-1, causing their downregulation [6].

Maturation and trafficking of the Salmonella-containing vacuole

When SCVs form, they acquire transiently cellular markers associated with the early endocytic pathway, e.g. the transferrin receptor (TfnR), early endosomal antigen 1 (EEA1) and several Rab GTPases such as Rab4, Rab5 and Rab11, and SCVs mature in a Rab7-dependent manner [11]. SCVs may then uncouple from the endocytic pathway, to avoid lysosomal fusion [11], although recent evidence suggests that late endosome/lysosome (LE/Lys) content is continually delivered to the SCV in a Rab7- and microtubule-dependent manner [12•]. Regardless of whether this LE/Lys interaction occurs, as the SCV matures, early markers are sequentially replaced by late endosome/lysosome markers including Rab7, vacuolar ATPase (v-ATPase) and lysosomal membrane glycoproteins (lpgs) e.g. LAMP-1 [11].

SopE and the inositol phosphatase activity of SopB are required for SCV recruitment of Rab5 [13,14••], which binds the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase Vps34 required for LAMP-1 recruitment [11,14••]. Vps34 in turn generates PI(3)P on the SCV membrane [14••], which is necessary for the recruitment of EEA1 [11]. SopB also inhibits the degradation of epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR) by lysosomes [15], and has been recently shown to recruit sorting nexin-1 (SNX-1), which likely contributes to the disappearance of late endosomal/lysosomal markers, such as the mannose 6-phosphate receptor, from the maturing SCV [16]. These observations in combination suggest that SopB plays a key role in diverting SCV trafficking from the endosomal maturation pathway. SopB is additionally required for activation of Akt [4], which in turn deactivates the Rab14 GAP, AS160. Activated Rab14 increases intracellular Salmonella replication, possibly by delaying SCV-lysosomal fusion [17••]. In addition, SpiC is thought to prevent fusion of macrophage late endosomes/lysosomes with the SCV [11].

The SPI-2 effector SseJ is required for full virulence during systemic infection of mice and localises to SCVs [18]. It has deacylase activity in vitro [19] and during Salmonella infection it esterifies cholesterol, a lipid enriched in SCV membranes. SseJ also exhibits phospholipase A activity [20].

The SPI-1 effector SopA structurally and functionally mimics cellular HECT E3 ubiquitin ligases [21•], promoting bacterial escape from the SCV in HeLa cells. It may, therefore, have a role in disrupting SCV integrity [11] although the significance of this activity is unclear.

Several hours post-infection of host cells, an F-actin meshwork assembles around the replicative SCV [11,22], which appears to be bound and stabilised by SipA [23]. Several SPI-2 effectors may also regulate SCV-associated actin dynamics. In particular, the kinase SteC is essential for the formation of SCV-associated F-actin [22], while SseI and SspH2 co-localise with SCV-associated F-actin and bind the host actin-crosslinking protein filamin [24]. Furthermore, SspH2 interacts with the cellular G-actin binding protein profilin and inhibits actin polymerisation rates in vitro [24]. The plasmid-encoded effector SpvB ADP ribosylates monomeric actin preventing its polymerisation and inhibits the formation of SCV-associated F-actin [24].

SCV positioning and formation of Salmonella-induced filaments (Sifs)

As it matures, the SCV migrates towards the perinuclear region of the host cell by transiently recruiting the Rab7-interacting lysosomal protein (RILP), which in turn associates with the minus end-directed microtubule motor, dynein [25]. Maintaining the SCV within the perinuclear region appears to be important for promoting bacterial replication. The close proximity of the SCV to the Golgi may facilitate interception of endocytic and exocytic transport vesicles to obtain nutrients and/or membrane [25]. In support of this, SifA, SseG and SseF are required for re-direction of exocytic transport vesicles to the SCV [26•].

SseG and SseF have been suggested to maintain the SCV in the perinuclear region by forming a functional complex [27] that either ‘tethers’ the SCV to the Golgi apparatus or manipulates dynein activity [25]. By contrast, SifA binds the host protein SKIP (SifA and kinesin interacting protein) to downregulate PipB2-induced recruitment of the plus end-directed microtubule motor kinesin to the SCV [28•,29••]. Efficient localisation of SifA to the SCV is mediated by the SPI-1 effector SipA [23]. SopB-mediated phosphorylation of the actin-associated motor myosin II light chain (MLC), most likely via the Rho/ROCK/MLC signalling pathway, is also required for retention of the SCV within the perinuclear region of the host cell [30•].

Once the SCV is positioned, the bacteria begin to replicate. This replicative stage is characterised by the formation of LAMP-rich specialised tubulovesicular structures termed Salmonella-induced filaments (Sifs) that extend away from the SCV along the microtubule network. Sifs are thought to be generated by fusion of late endosomes/lysosomes with the SCV [11], although their precise role in infection is undetermined. SifA is essential for Sif formation [11] and maintenance of SCV integrity [18]. Its transient overexpression is sufficient to induce swelling and aggregation of late endosomes and formation of Sif-like tubules in mammalian cells [11]. Although the molecular mechanism by which SifA induces Sif formation is unclear, the effector has been shown to interact with Rab7 and is suggested to promote Sif extension by uncoupling Rab7 from RILP, preventing the recruitment of dynein to Sifs [25]. The SPI-2 effector PipB2 also promotes Sif extension, most probably through a direct interaction with kinesin-1 [28•,31].

Both SseF and SseG are thought to augment Sif formation by modulating the aggregation of endosomal compartments. Salmonella mutants lacking sseF, sseG or another SPI-2 effector gene, sopD2 induce fewer Sifs compared with wild type bacteria, but form a greater number of filamentous aggregates with punctate LAMP-1 distribution within infected cells. These ‘pseudo-Sifs’ may represent Sif precursors [25,32].

By contrast, both SseJ and SpvB antagonise Sif formation. Mutation of sseJ or spvB increases the number of Sifs [25], and transfection of epithelial cells with SseJ before Salmonella infection inhibits Sif formation [18]. SseJ activity also appears to be required for loss of SCV integrity as, in contrast to a sifA mutant, a sifA sseJ double mutant retains its vacuolar membrane [18].

Modulation of the innate immune response and host cell death

SPI-1 effectors additionally induce acute intestinal inflammation, a hallmark of Salmonella infection. Stimulation of Cdc42 by SopE/SopE2/SopB during Salmonella invasion leads to Raf1-dependent upregulation of Erk, Jnk and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways and subsequent activation of the transcription factors AP-1 and NFκB [4,6,8•]. This results in the release of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-8, stimulating the recruitment of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs). Simultaneously, a SipA N-terminal region triggers a novel Arf6- and phospholipase D signalling cascade that activates protein kinase Cα, leading to apical secretion of the potent PMN chemoattractant hepoxillin A3 [4,33]. This promotes PMN transmigration across the epithelium into the intestinal lumen [4,33], which is probably augmented by the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of SopA [21•]. PMN transmigration appears to contribute towards diarrhoeal disease, enhancing Salmonella transmission via the faecal-oral route. Ins(1,4,5,6)P4 production via SopB inositol phosphatase activity also plays a role in the induction of diarrhoea by promoting cellular chloride ion secretion and fluid flux [4,6], while SopD contributes towards enteritis in infected calves through an unknown mechanism [4]. Disruption of intestinal epithelial cell tight junctions by SopB, SopE, SopE2 and SipA is also likely to promote fluid flux and PMN transmigration [34], although intriguingly, another SPI-1 effector, AvrA has been recently shown to counteract this activity [35].

Inflammatory responses are further augmented by effector-induced macrophage cell death. This was thought to be due to direct activation of caspase-1 by SipB, resulting in release of proinflammatory cytokines [4], but has been shown to depend on the delivery of flagellin into the macrophage cytosol, possibly via the SPI-1 T3SS [36]. SipB additionally triggers a delayed caspase-1-independent cell death [4,36]. More recently, SpvB and SseL have been reported to induce a slower SPI-2-dependent cell death pathway [37,38•].

Salmonella also deliver effectors that suppress cellular immune responses. Both SptP GAP and tyrosine phosphatase activities play a role in reversing MAPK activation [39,40] and AvrA acetyltransferase activity towards specific mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases (MAPKKs) prevents Jnk activation [41•]. SpvC also directly inhibits Erk, Jnk and p38 MAPKs through its phosphothreonine lyase activity [42,43].

Finally, Salmonella targets transcription factors downstream of MAPK pathways. The SPI-2 deubiquitinase SseL suppresses NFκB activation by impairing IκBα ubiquitination and degradation [44], an activity also reported for AvrA [45]. SspH1 additionally inhibits NFκB-dependent gene expression, possibly via ubiquitination of the host cell kinase PKN1 [46].

Perspectives–effector localisation and cooperation

Salmonellae have evolved an array of subversive SPI-1 and SPI-2 effector proteins with diverse biochemical activities. The actions of individual SPI-1 effectors during Salmonella entry have been intensively studied, but it is not clear which effectors are present in the host cell at any one time, nor are the sequence and kinetics of effector translocation established, although work has begun to dissect this complex process [47]. Likewise, it is still not completely understood how the discrete activities of all of these effectors are controlled, though effectors do appear to have varied half-lives following their translocation [6]. Work on the localisation of effectors has shown that in addition to the translocase SipB, six other SPI-1 effectors (SipA, SipC, SopB, SopE, SopE2 and SptP) are delivered to the host plasma membrane, suggesting that this may provide an interface for effector–effector interplay [48] as well as effector-target interaction(s) [49] during bacterial entry. Combinatorial screens [50] have confirmed known/proposed effector interactions [3,48], and suggested two novel cooperative associations, SipC–SopB and SipC–SopE [50], which require further investigation. However, interactions of SPI-2 effectors with their host cell targets, as well as with each other is a less well-understood area of Salmonella pathogenesis.

Recent work has challenged the conventional view that SPI-1 effectors solely mediate Salmonella invasion and SCV biogenesis, while SPI-2 effectors promote intracellular bacterial replication and systemic spread. SipA [23], SopB [30•] and SptP (Humphreys et al., unpublished) all persist in host cells hours after bacterial invasion and have key roles in SCV positioning and/or intracellular replication (Figure 1), suggesting possible interplay between SPI-1 and SPI-2 effectors. Indeed, SipA has already been shown to cooperate with SifA to mediate perinuclear SCV positioning [23]. Continued studies of effector action and interplay seem likely to explain further the processes underlying infection and highlight new facets of eukaryotic cell biology.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Acknowledgements

We thank Colin Hughes for his insightful comments on the manuscript. Work in VK’s laboratory is supported by a Wellcome Trust Programme grant (070266) and a Medical Research Council Project grant (G0500583).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.mib.2008.12.001.

Contributor Information

Emma J McGhie, Email: ejm37@cam.ac.uk.

Lyndsey C Brawn, Email: lb314@cam.ac.uk.

Peter J Hume, Email: pjh53@cam.ac.uk.

Daniel Humphreys, Email: dh309@cam.ac.uk.

Vassilis Koronakis, Email: vk103@cam.ac.uk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Filloux A., Hachani A., Bleves S. The bacterial type VI secretion machine: yet another player for protein transport across membranes. Microbiology. 2008;154:1570–1583. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/016840-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gal-Mor O., Gibson D.L., Baluta D., Vallance B.A., Finlay B.B. A novel secretion pathway of Salmonella enterica acts as an antivirulence modulator during salmonellosis. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000036. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayward R.D., Koronakis V. Direct modulation of the host cell cytoskeleton by Salmonella actin-binding proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Layton A.N., Galyov E.E. Salmonella-induced enteritis: molecular pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2007;9:1–17. doi: 10.1017/S1462399407000373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGhie E.J., Hayward R.D., Koronakis V. Control of actin turnover by a Salmonella invasion protein. Mol Cell. 2004;13:497–510. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel J.C., Galán J.E. Manipulation of the host actin cytoskeleton by Salmonella—all in the name of entry. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Popp D., Yamamoto A., Iwasa M., Nitanai Y., Maéda Y. Single molecule polymerization, annealing and bundling dynamics of SipA induced actin filaments. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2008;65:165–177. doi: 10.1002/cm.20252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8•.Patel J.C., Galán J.E. Differential activation and function of Rho GTPases during Salmonella-host cell interactions. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:453–463. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Using RNAi, the authors demonstrate that Rac and RhoG activation, by SopE and SopB respectively, contributes towards the cytoskeletal remodelling that occurs during Salmonella entry. By contrast, Cdc42 upregulation is required for eliciting pro-inflammatory nuclear responses associated with Salmonella infection.

- 9.Dai S., Zhang Y., Weimbs T., Yaffe M.B., Zhou D. Bacteria-generated PtdIns(3)P recruits VAMP8 to facilitate phagocytosis. Traffic. 2007;8:1365–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakowski M.A., Cirulis J.T., Brown N.F., Finlay B.B., Brumell J.H. SopD acts cooperatively with SopB during Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium invasion. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2839–2855. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steele-Mortimer O. The Salmonella-containing vacuole: moving with the times. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12•.Drecktrah D., Knodler L.A., Howe D., Steele-Mortimer O. Salmonella trafficking is defined by continuous dynamic interactions with the endolysosomal system. Traffic. 2007;8:212–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study uses high-resolution live cell imaging to show that the SCV undergoes continuous interaction with late endosomes/lysosomes following Salmonella invasion.

- 13.Mukherjee K., Parashuraman S., Raje M., Mukhopadhyay A. SopE acts as an Rab5-specific nucleotide exchange factor and recruits non-prenylated Rab5 on Salmonella-containing phagosomes to promote fusion with early endosomes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23607–23615. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14••.Mallo G.V., Espina M., Smith A.C., Terebiznik M.R., Alemán A., Finlay B.B., Rameh L.E., Grinstein S., Brumell J.H. SopB promotes phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate formation on Salmonella vacuoles by recruiting Rab5 and Vps34. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:741–752. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study the authors show that the SPI-1 effector SopB is necessary for PI(3)P accumulation on the SCV membrane, a critical requirement for vacuolar maturation. SopB inositol phosphatase activity recruits Rab5 to the SCV. Rab5 in turn associates with the PI3-kinase Vps34, which is responsible for PI(3)P production on the SCV membrane.

- 15.Dukes J.D., Lee H., Hagen R., Reaves B.J., Layton A.N., Galyov E.E., Whitley P. The secreted Salmonella dublin phosphoinositide phosphatase, SopB, localizes to PtdIns(3)P-containing endosomes and perturbs normal endosome to lysosome trafficking. Biochem J. 2006;395:239–247. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bujny M.V., Ewels P.A., Humphrey S., Attar N., Jepson M.A., Cullen P.J. Sorting nexin-1 defines an early phase of Salmonella-containing vacuole-remodeling during Salmonella infection. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2027–2036. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17••.Kuijl C., Savage N.D., Marsman M., Tuin A.W., Janssen L., Egan D.A., Ketema M., van den Nieuwendijk R., van den Eeden S.J., Geluk A. Intracellular bacterial growth is controlled by a kinase network around PKB/AKT1. Nature. 2007;450:725–730. doi: 10.1038/nature06345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Using an RNAi screen, this elegant study identified that the host kinase AKT1/PKB plays a central role in controlling intracellular bacterial growth. SopB was shown to activate AKT1, which subsequently delays phagosomal–lysosomal fusion through the AS160-RAB14 pathway.

- 18.Ruiz-Albert J., Yu X.J., Beuzón C.R., Blakey A.N., Galyov E.E., Holden D.W. Complementary activities of SseJ and SifA regulate dynamics of the Salmonella typhimurium vacuolar membrane. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44:645–661. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohlson M.B., Fluhr K., Birmingham C.L., Brumell J.H., Miller S.I. SseJ deacylase activity by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium promotes virulence in mice. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6249–6259. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6249-6259.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lossi N.S., Rolhion N., Magee A.I., Boyle C., Holden D.W. The Salmonella SPI-2 effector SseJ exhibits eukaryotic activator-dependent phospholipase A and glycerophospholipid: cholesterol acyltransferase activity. Microbiology. 2008;154:2680–2688. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/019075-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21•.Diao J., Zhang Y., Huibregtse J.M., Zhou D., Chen J. Crystal structure of SopA, a Salmonella effector protein mimicking a eukaryotic ubiquitin ligase. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:65–70. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study, the authors determine the crystal structure of the SPI-1 effector SopA and show that it has a high structural similarity to eukaryotic HECT E3 ligases. SopA therefore is an elegant example of a bacterial protein that has evolved as a structural and functional mimic of a eukaryotic enzyme.

- 22.Poh J., Odendall C., Spanos A., Boyle C., Liu M., Freemont P., Holden D.W. SteC is a Salmonella kinase required for SPI-2-dependent F-actin remodelling. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:20–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brawn L.C., Hayward R.D., Koronakis V. Salmonella SPI1 effector SipA persists after entry and cooperates with a SPI2 effector to regulate phagosome maturation and intracellular replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miao E.A., Brittnacher M., Haraga A., Jeng R.L., Welch M.D., Miller S.I. Salmonella effectors translocated across the vacuolar membrane interact with the actin cytoskeleton. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:401–415. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.t01-1-03456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramsden A.E., Holden D.W., Mota L.J. Membrane dynamics and spatial distribution of Salmonella-containing vacuoles. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26•.Kuhle V., Abrahams G.L., Hensel M. Intracellular Salmonella enterica redirect exocytic transport processes in a Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-dependent manner. Traffic. 2006;7:716–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this paper, the authors show that exocytic transport vesicles are redirected to the SCV through the combined actions of the SPI-2 effectors SifA, SseF and SseG.

- 27.Deiwick J., Salcedo S.P., Boucrot E., Gilliland S.M., Henry T., Petermann N., Waterman S.R., Gorvel J.P., Holden D.W., Méresse S. The translocated Salmonella effector proteins SseF and SseG interact and are required to establish an intracellular replication niche. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6965–6972. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00648-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28•.Henry T., Couillault C., Rockenfeller P., Boucrot E., Dumont A., Schroeder N., Hermant A., Knodler L.A., Lecine P., Steele-Mortimer O. The Salmonella effector protein PipB2 is a linker for kinesin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13497–13502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605443103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; These authors show that the SPI-2 effector PipB2 is required for the direct recruitment of kinesin-1 to the SCV, and therefore behaves as a SifA antagonist.

- 29••.Boucrot E., Henry T., Borg J.P., Gorvel J.P., Méresse S. The intracellular fate of Salmonella depends on the recruitment of kinesin. Science. 2005;308:1174–1178. doi: 10.1126/science.1110225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this paper, the authors convincingly show that the SPI-2 effector SifA interacts with a host protein of previously unknown function, which they subsequently named SKIP (SifA and kinesin-interacting protein). SKIP was demonstrated to downregulate kinesin recruitment to the SCV, ensuring maintenance of vacuolar integrity and perinuclear SCV positioning.

- 30•.Wasylnka J.A., Bakowski M.A., Szeto J., Ohlson M.B., Trimble W.S., Miller S.I., Brumell J.H. Role for myosin II in regulating positioning of Salmonella-containing vacuoles and intracellular replication. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2722–2735. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00152-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors demonstrate that the actin-based motor protein myosin II is recruited to the SCV and contributes towards the maintenance of SCV positioning and membrane integrity by counteracting the activity of the SPI-2 effectors PipB2 and SseJ. SopB was found to be required for SCV positioning and was sufficient to activate myosin II via phosphorylation of its regulatory light chain (MLC), most probably via the Rho/ROCK/MLC signalling pathway.

- 31.Knodler L.A., Steele-Mortimer O. The Salmonella effector PipB2 affects late endosome/lysosome distribution to mediate Sif extension. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4108–4123. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang X., Rossanese O.W., Brown N.F., Kujat-Choy S., Galán J.E., Finlay B.B., Brumell J.H. The related effector proteins SopD and SopD2 from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium contribute to virulence during systemic infection of mice. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:1186–1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wall D.M., Nadeau W.J., Pazos M.A., Shi H.N., Galyov E.E., McCormick B.A. Identification of the Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium SipA domain responsible for inducing neutrophil recruitment across the intestinal epithelium. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2299–2313. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyle E.C., Brown N.F., Finlay B.B. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium effectors SopB, SopE, SopE2 and SipA disrupt tight junction structure and function. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1946–1957. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao A.P., Petrof E.O., Kuppireddi S., Zhao Y., Xia Y., Claud E.C., Sun J. Salmonella type III effector AvrA stabilizes cell tight junctions to inhibit inflammation in intestinal epithelial cells. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fink S.L., Cookson B.T. Pyroptosis and host cell death responses during Salmonella infection. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2562–2570. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Browne S.H., Hasegawa P., Okamoto S., Fierer J., Guiney D.G. Identification of Salmonella SPI-2 secretion system components required for SpvB-mediated cytotoxicity in macrophages and virulence in mice. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;52:194–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38•.Rytkönen A., Poh J., Garmendia J., Boyle C., Thompson A., Liu M., Freemont P., Hinton J.C., Holden D.W. SseL, a Salmonella deubiquitinase required for macrophage killing and virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3502–3507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610095104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The identification of a previously uncharacterised SPI-2 effector, SseL, is described in this paper. SseL exhibits sequence similarities to cysteine proteases with deubiquitinating activity and was shown to possess deubiquitinase activity both in vitro and in vivo. In addition, SseL induced delayed cytotoxicity in macrophages and Salmonella strains lacking sseL were attenuated for virulence in mice.

- 39.Murli S., Watson R.O., Galán J.E. Role of tyrosine kinases and the tyrosine phosphatase SptP in the interaction of Salmonella with host cells. Cell Microbiol. 2001;3:795–810. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin S.L., Le T.X., Cowen D.S. SptP, a Salmonella typhimurium type III-secreted protein, inhibits the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by inhibiting Raf activation. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:267–275. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.t01-1-00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41•.Jones R.M., Wu H., Wentworth C., Luo L., Collier-Hyams L., Neish A.S. Salmonella AvrA coordinates suppression of host immune and apoptotic defenses via JNK pathway blockade. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; These authors show that the SPI-1 effector AvrA possesses acetyltransferase activity towards specific mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases (MAPKKs) and potently inhibits c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and NFκB signalling pathways in order to downregulate apoptosis of Salmonella-infected cells.

- 42.Mazurkiewicz P., Thomas J., Thompson J.A., Liu M., Arbibe L., Sansonetti P., Holden D.W. SpvC is a Salmonella effector with phosphothreonine lyase activity on host mitogen-activated protein kinases. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:1371–1383. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H., Xu H., Zhou Y., Zhang J., Long C., Li S., Chen S., Zhou J.M., Shao F. The phosphothreonine lyase activity of a bacterial type III effector family. Science. 2007;315:1000–1003. doi: 10.1126/science.1138960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Le Negrate G., Faustin B., Welsh K., Loeffler M., Krajewska M., Hasegawa P., Mukherjee S., Orth K., Krajewski S., Godzik A. Salmonella secreted factor L deubiquitinase of Salmonella typhimurium inhibits NF-κB, suppresses IκBα ubiquitination and modulates innate immune responses. J Immunol. 2008;180:5045–5056. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.5045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ye Z., Petrof E.O., Boone D., Claud E.C., Sun J. Salmonella effector AvrA regulation of colonic epithelial cell inflammation by deubiquitination. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:882–892. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rohde J.R., Breitkreutz A., Chenal A., Sansonetti P.J., Parsot C. Type III secretion effectors of the IpaH family are E3 ubiquitin ligases. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winnen B., Schlumberger M.C., Sturm A., Schüpbach K., Siebenmann S., Jenny P., Hardt W.D. Hierarchical effector protein transport by the Salmonella Typhimurium SPI-1 Type III secretion system. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raffatellu M., Wilson R.P., Chessa D., Andrews-Polymenis H., Tran Q.T., Lawhon S., Khare S., Adams L.G., Bäumler A.J. SipA, SopA, SopB, SopD, and SopE2 contribute to Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium invasion of epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73:146–154. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.146-154.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cain R.J., Hayward R.D., Koronakis V. The target cell plasma membrane is a critical interface for Salmonella cell entry effector-host interplay. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:887–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cain R.J., Hayward R.D., Koronakis V. Deciphering interplay between Salmonella invasion effectors. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000037. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.