Abstract

Ca2+ and the cell-surface calcium sensing receptor (CaSR) constitute a novel and robust ligand/receptor system in regulating the proliferation and differentiation of colonic epithelial cells. Here we show that activation of CaSR by extracellular Ca2+ (or CaSR agonists) enhanced the sensitivity of human colon carcinoma cells to mitomycin C (MMC) and fluorouracil (5-FU). Activation of CaSR up-regulated the expression of MMC activating enzyme, NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO-1) and down-regulated the expression of 5-FU target, thymidylate synthase (TS) and the anti-apoptotic protein survivin. Cells that were resistant to drugs expressed little or no CaSR but abundant amount of survivin. Disruption of CaSR expression by shRNA targeting the CaSR abrogated these modulating effects of CaSR activation on the expression of NQO1, TS, survivin and cytotoxic response to drugs. It is concluded that activation of CaSR can enhance colon cancer cell sensitivity to MMC and 5-FU and can modulate the expression of molecules involved in the cellular responses to these cytotoxic drugs.

Keywords: calcium sensing receptor, NQO1, thymidylate synthase, survivin, drug sensitivity

INTRODUCTION

The human parathyroid calcium sensing receptor (CaSR) can sense minute changes in extracellular Ca2+ concentration and respond to tightly regulate systemic Ca2+ homeostasis by coordinating the secretion of endocrine hormones [1]. Human colonic epithelium and colon carcinoma cell lines express CaSR [2–4]. The function of CaSR in the colon, however, is intimately associated with growth and differentiation control [2–6]. In normal human colonic crypts, CaSR expression is restricted to differentiating epithelial cells as these cells migrate from the bottom of the crypts towards the apex. A relatively high level of CaSR expression is found in cells at the apex of a crypt where they are fully differentiated, non-proliferating and ready to undergo apoptosis [4]. Rapidly proliferating stem cells at the base of a crypt, however, do not express CaSR [4]. Thus, CaSR expression in human colonic crypts is linked to differentiation and reduction of proliferation. Carcinomas, on the other hand, show a different pattern of CaSR expression. Differentiated carcinoma (still retaining some glandular or crypt structures) express a relatively lower level of CaSR while a loss of CaSR expression is found in undifferentiated carcinoma (with no glandular or crypt structure) or in the invasive front of a differentiated carcinoma [3, 4]. Because transformation of colonic mucosa is attributable to blockade of terminal differentiation resulting in regional expansion of proliferation [7] and CaSR expression is linked to normal differentiation while its loss of expression is associated with progression, we hypothesize that CaSR is a robust regulator of proliferation and differentiation in human colonic epithelial cells and that this function of CaSR is directly linked to how colon carcinoma cells respond to cytotoxic drugs.

When the culture medium (containing low Ca2+) of human colon carcinoma cell lines were changed to medium containing a physiologic concentration of 1.4 mM Ca2+, they assume a more differentiated and benign phenotype with a change in cell morphology, reduction in growth and invasive capability [3–6]. This ligand /receptor system modulates differentiation control pathways that underlie the changes in biologic phenotype. Most prominent of these pathways are the E-cadherin/ β-catenin/wnt signal pathway and cell cycle control pathway [3–6]. Because degree of differentiation in colon carcinomas can influence survival and differentiated carcinomas express CaSR [3, 4, 8, 9], we hypothesize that this ligand/receptor system could modulate cellular sensitivity to cytotoxic drugs. The goal of this study was to determine if activation of CaSR by extracellular Ca2+ could modulate the cytotoxic response of human colon carcinoma cells to fluorouracil (5-FU) and mitomycin C (MMC) and assess the potential mechanisms underlying such modulation.

We chose 5-FU and MMC in this study because 5-FU is a drug of choice for treating colon cancer [10] while the alkylating agent MMC possesses marginal activity against this disease [11]. The molecular target of 5-FU is thymidylate synthase (TS), a key enzyme in the de novo synthesis of DNA [10]. Increased TS expression in tumors is an underlying mechanism by which tumor cells can escape from the toxic effect of 5-FU and become drug resistance [10]. MMC is an anti-tumor quinone which requires bioreductive activation to alkylate and crosslink cellular DNA efficiently [11]. The cytosolic NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1(NQO-1 [also known as DT-diaphorase]) is an important enzyme in mediating the bioreductive activation of MMC and decreased bioreductive activation of MMC is associated with the development of MMC resistance [12,13]. In addition to drug targets and drug activation, a critical determinant underlying sensitivity or resistance to cytotoxic drugs is the ease in which tumor cells undergo drug induced apoptosis [14–16]. Resistance to the induction of apoptosis is a well-defined characteristic of drug resistant cancer cells. Survivin is a well known anti-apoptotic protein and its function in blocking apoptosis and promoting drug resistance is well- characterized [17–19].

In this report, we showed that activation of CaSR enhanced the cytotoxic response of human colon carcinoma cells to MMC and 5-FU by modulating the expression of molecules that are intimately associated with drug sensitivity or resistance. We also found that drug resistant cells did not express CaSR but expressed a relatively high level of survivin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and cytotoxicity assays

Human colon carcinoma CBS, Moser, Fet and SW480 cells were maintained in SMEM medium (Ca2+-free, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with sodium bicarbonate, peptone, vitamins, amino acids and 5% fetal bovine serum as described previously [3–4]. Because fetal bovine serum contains approximately 3.5 to 4 mM Ca2+, the culture medium contained a low concentration of Ca2+ (0.175 to 0.2 mM). To assess the effect of Ca2+ on the cytotoxic response to drugs, the medium of actively growing cells was replenished with medium containing a physiologic concentration of 1.4 mM Ca2+, or a range of Ca2+ concentrations as indicated in the figures and 30 μM MMC or 15 μM 5-FU. The medium of a parallel set of cultures was replenished with medium only containing drugs without the addition of exogenous Ca2+. The medium of control cultures was replenished with regular culture medium without drugs or exogenous Ca2+. Cells were then incubated at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for the time periods as indicated in the figure legends. MMC was purchased from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN) and 5-FU was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Trypan blue dye exclusion [20] and MTS assays were used to determine the cytotoxic response to MMC or 5-FU. Dye exclusion assay was performed in 24-well culture plates with equal number of cells seeded into each well. Briefly, control cells and cells treated with drugs in the absence or presence of exogenous Ca2+ were detached by trypsinization and suspended in phosphate buffered saline containing 0.4% (w/v) trypan blue. The number of viable (unstained, dye excluding) cells were determined with the aid of a hemocytometer and the results were expressed as percent of cells killed by comparison to untreated control cultures. The cells from each culture well were routinely counted three times and the average of these values was taken to represent the value from one well. The results presented here represent the mean and standard error of the mean of three independent determinations from three separate experiments.

MTS assay was performed using a CellTiter96™.AQueous Assay (MTS) kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to instructions provided by the manufacturer. Briefly, 5×103 cells were seeded into each well of 96-well culture plates and incubated at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for 24 hours. The medium was then replenished with medium containing 30 μM MMC or 15 μM 5-FU in the absence or presence of a range of Ca2+concentrations as shown in Fig. 1B or in the absence or presence of Gd3+ (25 μM) or neomycin (350 μM) as shown in Fig. 1C. Cells were then incubated at 37°C in the CO2 incubator for 24 hours. The cells were then rinsed with plain SMEM medium followed by the addition of CellTiter96™ Aqueous One Solution Reagent to the culture wells according to manufacturer’s instruction. The absorbance at 490 nm was then recorded using a μQuant Micro-Plate Reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT). Results were expressed as percent cells killed by comparison to untreated control cultures. Results shown represent the mean and standard error of the mean of three independent experiments.

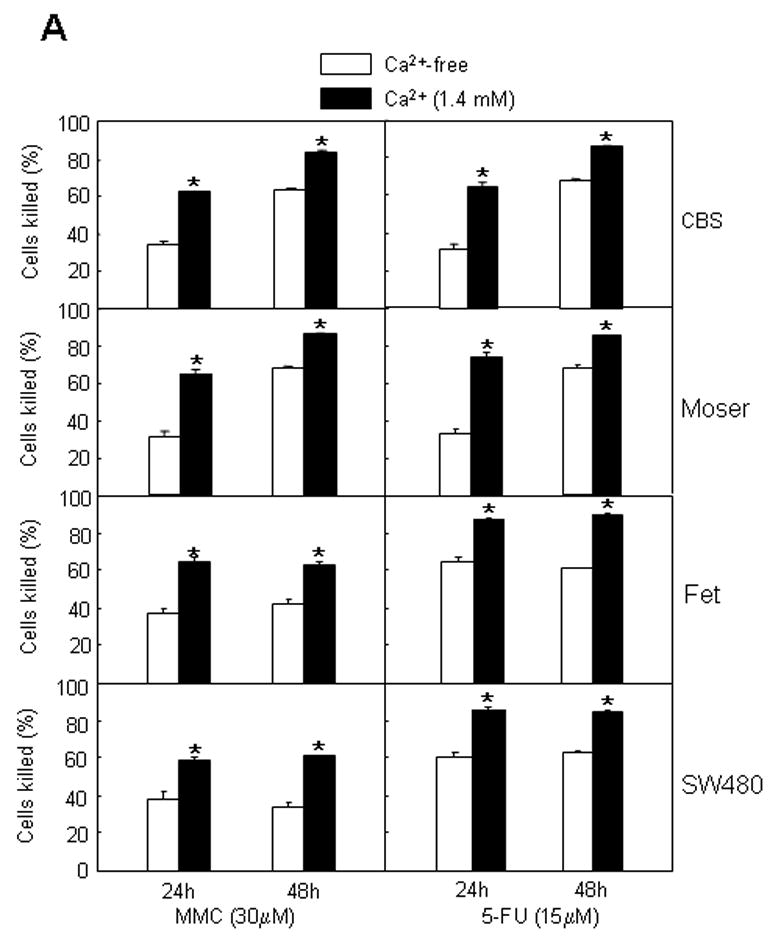

Figure 1.

Activation of CaSR by extracellular Ca2+ and the CaSR agonists Gd3+ and neomycin enhances the cytotoxic response of human colon carcinoma CBS, Moser, Fet and SW480 cells to MMC and 5-FU. (A) Trypan blue dye exclusion method [20] was used to determine the cytotoxic response to MMC or 5-FU and was performed in 24 well culture plates as described in Methods. Cells were exposed to drugs for 24 or 48 hours in culture medium (without the addition of exogenous Ca2+) or in medium containing exogenous Ca2+ (1.4 mM). Results are expressed as percent cells killed by comparison with control cultures and represent the mean and standard error of the mean of three independent experiments. Hollow bars, cells cultured in medium without exogenous Ca2+. Solid bars, cells cultured in medium containing Ca2+ (1.4mM). Asterisk (*) indicates p<0.01 compared to controls. (B) MTS assays were performed in 96 well culture plates as described in Methods to determine the cytotoxic response to MMC and 5-FU. Cells were exposed to drugs for 24 hours in culture medium (without the addition of exogenous Ca2+) or in medium containing different exogenous Ca2+ concentrations as indicated. The results are expressed as percent cells killed by comparison with control cultures. The results presented here represent the mean and standard error of three independent experiments. (C) MTS assays, in 96-well plates, were used to determine the effects of Gd3+ and neomycin (Neo) on the cytotoxic response to MMC and 5-FU. Cells were exposed to drugs for 24 hours in plain medium or in medium containing 25 μM Gd3+ or 350 μM Neo. Results are expressed as percent cells killed by comparison with control cultures in the absence of drugs. The results presented here represent the mean and standard error of three independent experiments. Hollow bars, cells cultured in Gd3+ and Neo-free medium as controls. Cross bars, cells cultured in medium containing Gd3+ (25 μM). Solid bars, cells cultured in medium containing Neo (350 μM). Asterisk (*) indicates p<0.01 compared with control.

Construction of shRNA expression vector (shRNA-CaSR) targeting the CaSR, transfection, selection and development of stable transfectants

shRNA-CaSR expression vector was constructed in pRNA-U6.1/Hygro under the control of U6 promoter and contains a hygromycin-resistant gene for the selection of stable transfectants for hygromycin resistance. shRNA-CaSR was purchased from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). The target sequence-ATCCCGCTCCGGCCTTGATTTGA GATCTTGATATCCGGATCTCAAATCAAGGCCGGAGTTTTTTCCAAA- was designed by the company’s shRNA Target Finder and DesignTool. The underlined sequence represents the target sequence of CaSR inserted into pRNA-U6.1/Hygro. pRNA-U6.1/Neo/Ctrl (GenScript Co., Piscataway, NJ) with a scrambled insert was used as a control vector (shRNA-Ctrl) in transfection experiments.

Plasmids shRNA-CaSR or shRNA-Ctrl were transfected into CBS carcinoma cells using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Frederick, MD) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The stable shRNA-CaSR or shRNA-Ctrl transfectants were established by selection of the cells with 200μg/ml of hygromycin B for shRNA-CaSR transfected cells or 500 μg/ml of G418 for shRNA-Ctrl transfected cells. Clones of stable transfectants were obtained by the use of cloning cylinders. Transfectants were routinely cultured in SMEM medium containing 50 μg/mL of hygromycin B (shRNA-CaSR transfected) or 200 μg/ml of G418 (shRNA-Ctrl transfected).

Immunocytochemistry and quantitation of the preponderance of CaSR and survivin expression before and after drug treatment

Cells were cultured on glass cover slips placed in 24-well cultured plates. Equal number of cells (1×105) was seeded into each well. Cells were cultured to 70% confluence and then treated with MMC or 5-FU with the concentrations of drugs and duration of treatments as indicated in the figures. Immunocytochemical staining with anti-human CaSR (Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO) or anti-human survivin antibodies (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) was performed using the ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, cells on cover slips were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 4°C. Membrane permeabilization was accomplished by treatment with 100% methanol at −20°C for 5 min. Cellular endogenous peroxidase activity was then quenched with PBS containing 0.3% serum and 0.3% H2O2 for 5 min at room temperature. Non specific peroxidase activity was further blocked with normal blocking serum (supplied with the ABC kit’s manufacturer) for 20 min at room temperature.

Both primary antibodies at a dilution of 1:2,000 in PBS were used in these experiments. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies (PBS in the absence of primary antibodies and blocking peptides in the presence of antibodies served as controls) for 30 min at room temperature, washed and incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody, ABC reagent and DAB substrate according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were then counterstained with Mayer’s Hematoxylin Solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Immunostaining of the cells was evaluated and scored under a phase contrast microscope. One hundred cells from each of a set of triplicate slides from one experiment was scored as positive or negative according to the relative intensity of staining. An example of the selection criterion for CaSR and survivin staining is shown in Figure 2A and 2C, respectively.

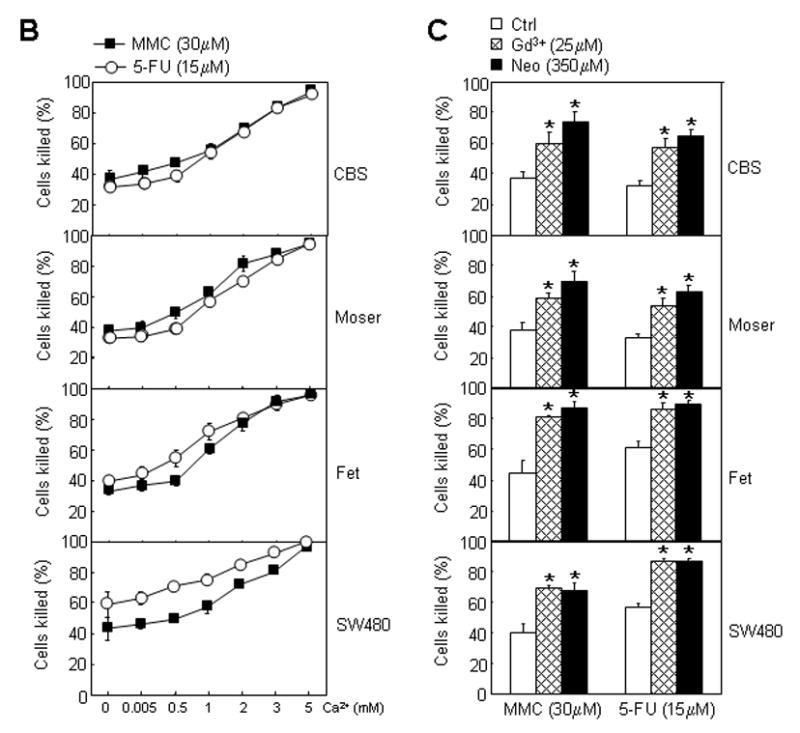

Figure 2.

CaSR and survivin expression in drug resistant cells. Immunocytochemical methods were used to assess the preponderance of CaSR and survivin expression in cells that survived treatment with MMC or 5-FU. Cells were cultured on coverslips placed in 24-well culture plates and treated with MMC or 5-FU for 24 hours as described in Methods. Control cells were similarly cultured but without drugs. Attached viable cells that survived drug treatments were then processed for immunocytochemcal staining with anti-CaSR or anti-survivin antibodies. (A) Example of a cell that was scored CaSR positive (CaSR+) and example of a cell that was scored CaSR negative (CaSR-). (B) Preponderance of CaSR positive and CaSR negative cells following exposure to MMC or 5-FU. Approximately 100 cells per view in the microscope were scored according to this criterion. Hollow bars, CaSR positive cells; solid bars, CaSR negative cells. Error bars, standard error of the mean of three independent experiments. (C) Example of a cell that was scored survivin negative (survivin-) and example of a cell that was scored survivin positive (survivin+). (D) Preponderance of survivin positive and survivin negative cells following exposure to MMC or 5-FU. Approximately 100 cells per view in the microscope were scored according to this criterion. Hollow bars, survivin positive cells; solid bars, survivin negative cells. Error bars, standard error of the mean of three independent experiments.

Western blots

Western blottings were performed essentially as previously described [3, 4]. Total cell lysates were prepared in lysate buffer (50 mmol/L Tris pH 7.5, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 1.0 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5% NP40, 0.5% Triton X-100, 2.5 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate, 10 μL/mL protease inhibitor cocktail (EMD chemicals Inc., San Diego, CA) and 1 mmol/L PMSF). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bio-Rad dye binding assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Cellular proteins were fractionated by reducing SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, blocked (5% nonfat dried milk in 1x TBS buffer containing 0.1% Tween 20) and immunostained with primary antibodies. Primary antibodies used were the above described anti-human CaSR (which recognizes a 120-kDa CaSR band) and anti-human survivin antibodies; anti-human TS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and anti-human NQO-1 (IMGENEX Co., San Diego, CA). Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies in conjuction with chemiluminescence detection and the FUJIFILM LAS-3000 system (Fujifilm Life Science, Stamford, CT) were used to visualize the binding of primary antibodies to immobilized proteins of interest on the membranes. β-actin expression (using anti-human β-actin antibody (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA)) was used as internal controls for equal protein loading.

Quantitative analysis of protein expression was performed using Multi Gauge-Image software installed in the FUJIFILM LAS-3000 system. Densitometric fold increase or decrease in protein expression, by comparison with control lanes, was calculated. The numbers on the blots represent fold differences by comparison with control lanes with an assigned value of 1.

RESULTS

Modulation of cytotoxic response to MMC and 5-FU by extracellular Ca2+ and CaSR agonists

Figure 1A shows that extracellular Ca2+, in physiologic concentration of 1.4 mM, could enhance the sensitivity of human colon carcinoma CBS, Moser, Fet and SW480 cells to MMC and 5-FU. In the presence of exogenous Ca2+, the percent of cells killed after treatment with MMC or 5-FU for 24 hours, was almost doubled that of cells killed in the absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 1A). More cells (either in the presence or absence of Ca2+) were killed after exposure to drugs for 48 hours. The magnitude of the differential response observed between Ca2+ and control conditions had diminished after 48 hours of exposure to drugs (Fig. 1A). Nevertheless, this observed differences in the cytotoxic response between these 2 groups, after 48 hours of drug treatment, were still of statistical significance (unpaired Student’s t test. P<0.05). Figure 1B shows the promotion of the cytotoxic response to MMC and 5-FU over a range of extracellular Ca2+ concentrations (0.005 to 5mM). Concentrations higher than physiological were more effective in enhancing the sensitivity of these colon carcinoma cells to MMC and 5-FU.

If activation of CaSR by extracellular Ca2+ could promote sensitivity to MMC and 5-FU, then activation of CaSR by other receptor agonists such as Gd3+ or neomycin should have similar effects. Fig. 1C shows that both Gd3+ and neomycin enhanced the sensitivity of these colon carcinoma cells to MMC and 5-FU.

Lack of CaSR expression and high level of survivin expression correlates with resistant to MMC and 5-FU

Because CaSR functions to sense extracellular Ca2+ concentrations and is activated by extracellular Ca2+ [1], we hypothesized that CaSR mediates the action of extracellular Ca2+ in modulating the cellular responses to drugs. Because the anti-apoptotic protein survivin plays an important role in drug resistance, we also hypothesized that drug resistant cells express a relatively high level of survivin. We next focused on the role of CaSR and survivin in drug resistance in the CBS cells, a moderately differentiated human colon carcinoma cell line which is quite responsive to the growth-inhibitory and differentiation-promoting effect of extracellular Ca2+ and is one of the better characterized cell line in terms of its responsiveness to extracellular Ca2+ [3–6]. In addition, we were able to generate stable CaSR knocked-down cells in the CBS line, which should offer a greater ease in the elucidation of underlying mechanisms. Immunocytochemical analyses of CaSR and survivin expression showed that the expression of these molecules in the CBS line was heterogeneous and expression levels ranged from no expression to intermediate and high level of expression. Examples of CaSR negative, CaSR positive, survivin positive and survivin negative cells are shown in Figure 2A and 2C. We first determined the preponderance of CaSR and survivin expression by immunocytochemistry in the CBS cells and in drug resistant cells that survived a 24 hour exposure to MMC or 5-FU. A majority of the CBS cells (before drug treatment) was CaSR positive while only about 10 to 20 percent of the cells were CaSR negative (Fig. 2B) as defined by the criterion shown in Figure 2A. A progressive reversal of this proportion was observed with surviving cells exposed to increasing concentration of drugs (Fig. 2B). Seventy to 75 percent of the cells that survived MMC (30 μM) and 5-FU (15 μM) were now CaSR negative (Fig. 2B). Before drug exposure, about sixty percent of the CBS cells were survivin positive. The proportion of survivin positive cells rose to 90 percent in cells that survived treatment with MMC (30 μM) and 5-FU (15 μM) (Fig. 2D).

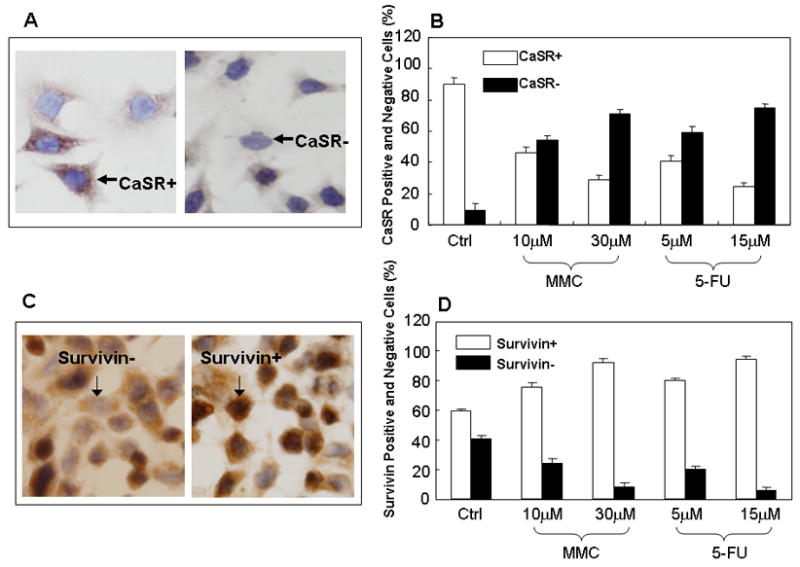

We then used Western blots to determine and confirm the level of CaSR and survivin expression in cells that survived treatment with MMC or 5-FU. Cells were treated with the cytotoxic drugs for 2, 6, 24, and 48 hours, respectively and cell lysates were prepared from viable attached cells that had initially survived drug treatment (i.e. drug resistant cells) for western blottings. Figure 3A shows a progressive decrease in CaSR expression in response to progressive increase in the duration of drug exposure. We observed a decrease in CaSR expression, in cells that survived drug treatment, as early as after 2 hours of exposure to drugs while an almost total loss of CaSR expression was observed in cells that survived 48 hours of drug exposure (Fig. 3A). The opposite was true in regard to the expression of survivin. Figure 3B shows a progressive increase in survivin expression in drug resistant cells in response to the progressive increase in the duration of drug exposure. A high level of survivin expression was observed in cells that survived 24 and 48 hours of exposure to MMC or 5-FU (Fig. 3B). The results of these experiments, taken together, show that cells that survived drug treatment and were, therefore, relatively drug resistance were predominantly CaSR negative and expressed a high level of survivin while the CaSR positive cells were relatively sensitive to drugs and were first killed by drugs. These results also suggest that CaSR is involved in modulating the effects of extracellular Ca2+.

Figure 3.

Western blot analyses of the expression of CaSR and survivin after treatment with MMC or 5-FU. Western blottings of cell lysates were performed as previously described (3–4). Treatment of cells with MMC or 5-FU was performed as described in Methods with the exception that cells were cultured in 25 cm2 culture flasks. Cell lysates were prepared from viable attached cells after various time of exposure to drugs as indicated in the figure. (A) CaSR expression. Lane 1, untreated control CBS cells; lane 2, cells treated with MMC; lane 3, cells treated with 5-FU. (B) Survivin expression. Lane 1, untreated controls; lane 2, cells treated with MMC; lane 3, cells treated with 5-FU. Number on top of each band indicate the densitometric fold increase or decrease in protein expression compared with control lanes (lane 1).

Extracellular Ca2+ and Gd3+ modulates the expression of NQO-1, TS and survivin through the CaSR

In a final series of experiments, we determined the potential mechanisms by which Ca2+ or the CaSR agonist Gd3+ could modulate the cellular sensitivity to MMC and 5-FU and whether CaSR function was required for this modulation. It is known that the bioreductive activation of MMC is required for the anti-tumor effect of MMC and that inefficient reductive activation of MMC is associated with MMC resistance [11–13]. It is also known that TS is the major cellular target of 5-FU and increased TS expression underlies 5-FU resistance [10] while increased expression of the anti-apoptotic protein survivin can confer resistance to a variety of anti-cancer drugs [14, 17]. If extracellular Ca2+ or Gd3+ could modulate cellular sensitivity to MMC and 5-FU, we hypothesized that extracellular Ca2+ or Gd3+ modulates the level of expression of NQO-1, TS and survivin. In addition, we hypothesized that these modulating effects of extracellular Ca2+ or Gd3+ acted through the CaSR.

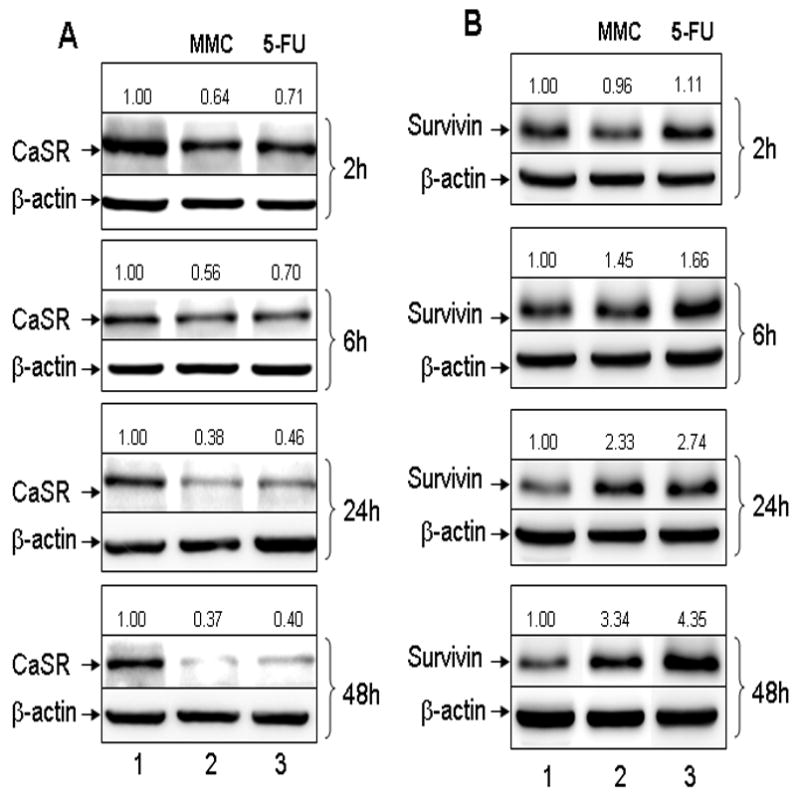

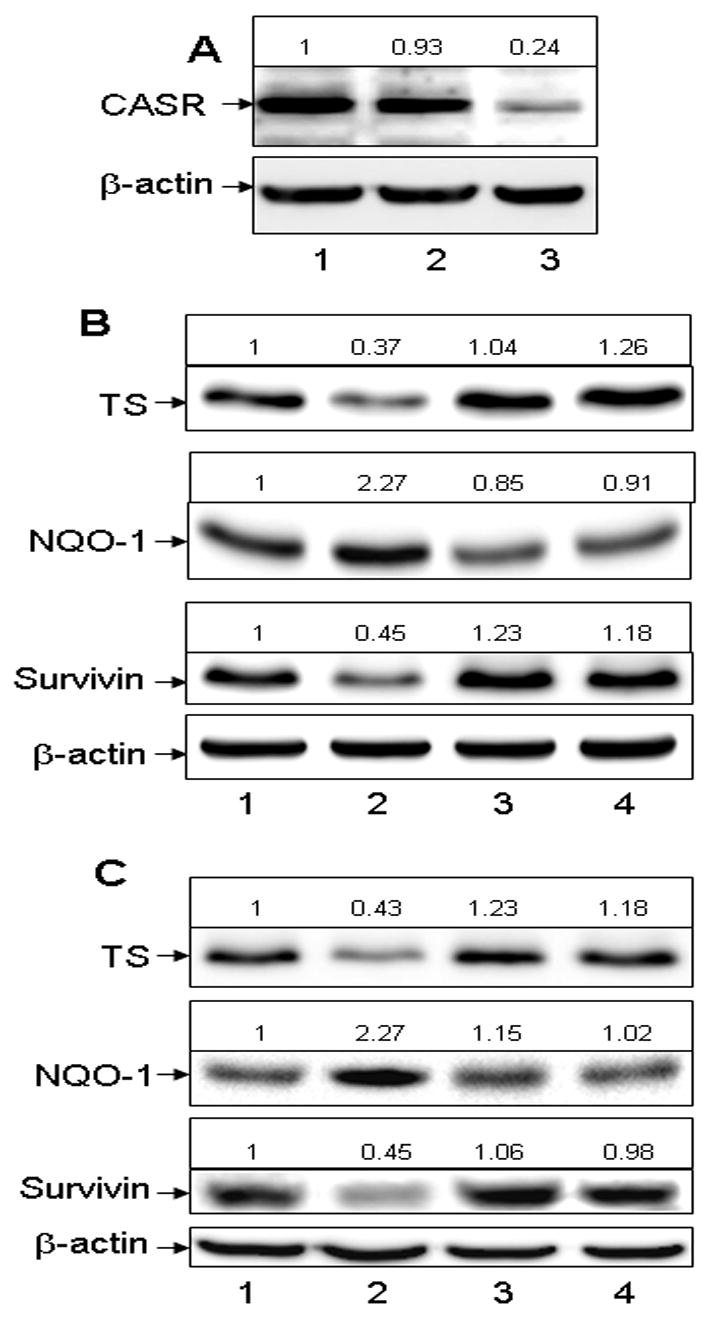

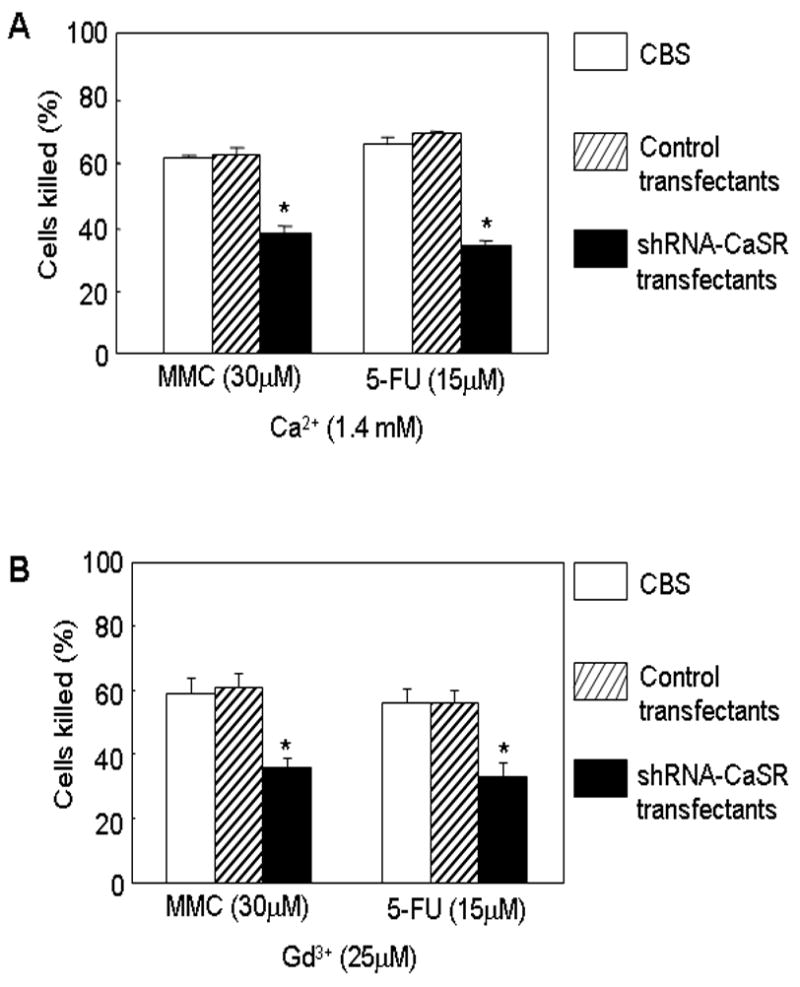

We used a shRNA approach targeting the CaSR to determine the role of CaSR in mediating the action of extracellular Ca2+ and Gd3+. Expression of shRNA-CaSR in the CBS cells (but not control vector transfected cells) effectively disrupted the expression of CaSR (Fig 4A). In the parental cells, extracellular Ca2+ down-regulated the expression of TS and survivin and up-regulated the expression of NQO-1 (Fig. 4B, lanes 1–2). Interestingly, cells with disrupted CaSR expression had a higher level of TS and survivin expression by comparison with the parental control cells (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 and 3). Disrupting CaSR expression by shRNA-CaSR abrogated the modulating effect of extracellular Ca2+ on the expression of TS, NQO-1 and survivin (Fig. 4B, lanes 3–4) and circumvented the enhancing effect of extracellular Ca2+ on the cytotoxic responses to MMC and 5-FU (Fig. 5A). Thus, extracellular Ca2+ down-regulated the expression of TS and survivin, up-regulated the expression of NQO-1 and enhanced cellular sensitivity to 5-FU and MMC. Knocking down CaSR expression abrogated these modulating effects of extracellular Ca2+. Likewise, Gd3+ down-modulated the expression of TS and survivin and up-regulated the expression of NQ0-1 in the parental control cells but not in CaSR knocked-down cells (Fig. 4C). Disrupting CaSR expression also circumvented the enhancing effect of Gd3+ on the cytotoxic responses to MMC and 5-FU (Fig. 5B).

Figure 4.

Disruption of CaSR expression blocks the modulating effect of Ca2+ and Gd3+ on the expression of TS, NQO1 and survivin (A) Stable transfection with a shRNA expression vector targeting the CaSR (shRNA-CaSR) disrupted the expression of CaSR. Lane1, Parental control cells; lane 2, Control (shRNA-Ctrl) transfected cells; lane 3, shRNA-CaSR transfected cells. (B) Disruption of CaSR expression blocks the modulating effect of Ca2+ on the expression of TS, NQO1 and survivin. Lane 1, parental control cells; lane 2, cells exposed to 1.4 mM Ca2+ for 24 hours; lane 3, shRNA-CaSR transfectants; lane 4, shRNA-CaSR transfectants exposed to 1.4 mM Ca2+ for 24 hours. (C) Disruption of CaSR expression blocks the modulating effect of Gd3+ on the expression of TS, NQO1 and survivin. Lane 1, parental control cells; lane 2, cells exposed to 25 μM gadolinium for 24 hours; lane 3, shRNA-CaSR transfectants; lane 4, shRNA-CaSR transfectants exposed to 25 μM gadolinium for 24 hours.

Numbers on top of each band indicate the densitometric fold increase or decrease in protein expression compared with controls (lane 1).

Figure 5.

Disruption of CaSR expression blocks the enhancing effect of Ca2+ and Gd3+ on the cytotoxic response to MMC and 5-FU. (A) These experiments were performed as described in the legends to Fig. 1A in medium containing 1.4 mM Ca2+. Parental cells, shRNA-Ctrl and shRNA-CaSR transfectants were exposed to MMC or 5-FU for 24 hours and their cytotoxic response to drugs evaluated. Hollow bars, parental control cells. Slashed bars, control transfectants. Solid bars, shRNA-CaSR transfectants. Asterisk (*) indicates p<0.01 compared to controls without drugs. (B) These experiments were performed as described in the legends to Fig. 1C in medium containing 25 μM Gd3+. Parental cells, shRNA-Ctrl and shRNA-CaSR transfectants were exposed to MMC or 5-FU for 24 hours and their cytotoxic response to drugs evaluated. Hollow bars, parental CBS cells. Slashed bars, control transfectants. Solid bars, shRNA-CaSR transfectants. Asterisk (*) indicates p<0.01 compared with CBS control cells.

DISCUSSION

The chemopreventive properties of Ca2+ in colon cancer are well-established [21–22] and are the subject of much recent interest. How Ca2+ acts at the molecular level to suppress or delay colon carcinogenesis, i.e. its mechanism of chemopreventive action, is not understood. Recent studies suggest that CaSR and extracellular Ca2+ function together to promote differentiation and suppress the malignant properties of human colon adenocarcinoma cells in vitro and that the mechanisms of action of this ligand receptor system are intimately associated with differentiation control in colonic epithelial cells. These mechanisms include the promotion of E-cadherin expression and suppression of β-catenin/wnt pathway, blockade of cell-cycle progression and the restoration of cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion [3–6]. Correlative immunohistochemical studies using pathological specimens of human colon also suggest that CaSR is a key player in proliferation and differentiation in the colonic epithelium. CaSR expression is associated with differentiation and suppression of β-catenin/wnt pathway while loss of CaSR expression is associated with malignant progression and activation of β-catenin/wnt pathway [3–6]. Interestingly, recent epidemiological studies show that variants of CaSR from the most common diplotype are significantly associated with the risk of advanced adenoma [23].

In this study, we showed that extracellular Ca2+ or CaSR agonists (Gd3+ and neomycin) enhanced the cytotoxic response of human colon adenocarcinoma cells to MMC and 5-FU and modulated the expression of molecules involved in the cellular sensitivity or resistance to these cytotoxic drugs. This enhancing and modulating effect of extracellular Ca2+ or Gd3+ requires a functional CaSR because knocking down CaSR expression abrogated the effect of extracellular Ca2+ or Gd3+. In addition, CaSR negative cells were found to be resistant to cytotoxic drugs. We hypothesize that these modulating effects of extracellular Ca2+ (or Gd3+) are directly linked to the function of this ligand/receptor system in differentiation control. Ca2+ inhibits cell growth and induces differentiation in colon adenocarcinoma cells [2–6]. TS is a key enzyme involved in the de novo synthesis of DNA and is the molecular target of 5-FU [24, 25]. 5-FU poisons TS, disrupts DNA synthesis and kills cells. Cancer cells that express a high level of TS circumvent the efficacy of 5-FU and are relatively resistant to this drug [26, 27]. Because Ca2+ induces growth inhibition and differentiation, there is less de novo synthesis of DNA in growth inhibited and differentiated cells. Thus, the level of TS expression is reduced and the reduction in TS expression is linked to growth inhibition and differentiation induction. Reduced TS expression may be directly responsible for the increase in sensitivity to 5-FU. Increased expression of survivin is also associated with resistance to cytotoxic drugs and cell proliferation [18–20]. Likewise, survivin level is suppressed in cells that are more differentiated and growth inhibited. The suppression of TS and survivin expression together may be responsible for the dramatic increase in sensitivity to 5-FU while the suppression of survivin expression alone may also contribute to the increase in sensitivity to MMC. It is well established that survivin is an anti-apoptotic protein and high level of survivin expression is known to block the ease in which the apoptotic process is induced and resistance to apoptosis is known to translate into anti-cancer drug resistance [17–19]. Because CaSR activation down-regulates the expression of survivin, it is likely that an induction in the ease of apoptosis is an underlying mechanism in the promotion of a cytotoxic response. The modulation of survivin is not uniquely associated with the CBS cells. We have now also observed down-regulation of survivin upon CaSR activation in the other cell lines (not shown). It should be pointed out that CaSR function may be dependent on the cells and tissues in which it is expressed. For example, CaSR is also involved in regulating osteoclast differentiation [28] and promotes apoptosis in a variety of cell type [29, 30]. In fibroblasts, however, CaSR regulates cell survival and is anti-apoptotic [31].

NQO1 is a cytosolic chemoprotective enzyme that catalyzes the metabolic detoxification of quinones and protects cells against redox cycling and oxidative stress [32–34]. It is not clear why NQO1 expression is increased in growth inhibited and differentiated cells. Nevertheless, NQO1 is a key enzyme involved in the bioreductive activation of MMC. It has been shown that reduced level of bioreductive activation of MMC is responsible for MMC resistance in colon cancer cells [13]. Therefore, Ca2+ (or Gd3+) induced up-regulation of NQO1 expression may be directly responsible for the increase in sensitivity to MMC while down-regulation of survivin expression may also contribute to the overall increase in sensitivity to MMC. Currently, MMC is not particular useful in treating colon cancer. It is intriguing that CaSR activation could modulate the expression of NQO-1 that is involved in MMC activation and promoted sensitivity to this drug. Whether MMC in combination with 5-FU along with CaSR activation will improve on therapeutic efficacy is not known and will require further studies. From a clinical perspective, TS is linked to resistance to 5-FU while survivin is linked to resistance to variety of cytotoxic drugs. Thus, down-modulation of TS and survivin together should offer a significant advantage to a therapeutic regimen containing 5-FU. 5-FU (in combination with oxaliplatin and/or irinotecan) is the main stay of cytotoxic therapy for colon cancer. Therefore, it is very likely that CaSR activation will promote sensitivity to a regimen containing 5-FU and other cytotoxics. The type of regimen (5-FU in combination with other drugs) that will provide the maximum benefit upon CaSR activation is, however, is not known and will require further investigation.

In the CaSR knocked-down cells, we observed an increase in the expression of TS and survivin. CaSR, in response to extracellular Ca2+, may down-regulate the basal expression of these molecules. When CaSR expression is reduced or lost, the cellular response to extracellular Ca2+ may be attenuated and thus, allowing for a higher expression of TS and survivin. CaSR and extracellular Ca2+ may function together to modulate the basal expression of these molecules. If CaSR can be activated in vivo in colon carcinomas, it should improve therapeutic efficacy. A variety of agonists can activate the CaSR. Thus, it is attractive to develop non-toxic CaSR agonists for this purpose. An alternative approach is to bypass the receptor and activate post receptor mechanisms that are responsible for the modulation of TS and NQO-1. This approach is particulerly attractive because it should also kill cancer cells that do not express CaSR.

In summary, extracellular Ca2+ (or Gd3+) enhanced the cytotoxic response of human colon carcinoma cells to 5-FU and MMC and modulated the expression of TS, NQO1 and survivin which are intimately associated with sensitivity or resistance to these drugs. These effects of extracellular Ca2+ is CaSR dependent because knocking down the expression of CaSR by shRNA abrogated both the enhancement of cytotoxic response to drugs and the modulating effects on the expression of TS, NQO1 and survivin. CaSR negative cells were found to be more resistant to these cytotoxic drugs.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD; Grant number: R01 CA47775

The abbreviations used are

- CaSR

calcium sensing receptor

- NQO-1, NAD(P)H

quinone oxidoreductase 1

- TS

Thymidylate Synthase

- MMC

mitomycin C

- 5-FU

Fluorouracil

- shRNA-CaSR

shRNA expression vector targeting the CaSR

- shRNA-Ctrl

shRNA -scrambled control vector

References

- 1.Brown EM, Pollak M, Hebert SC. The extracellular calcium-sensing receptor: its role in health and disease. Ann Rev Med. 1998;49:15–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kállay E, Bajna E, Wrba F, Kriwanek S, Peterlik M, Cross HS. Dietary calcium and growth modulation of human colon cancer cells: role of the extracellular calcium- sensing receptor. Cancer Detect Prev. 2000;24:127–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chakrabarty S, Radjendirane V, Appelman H, Varani J. Extracellular calcium and calcium sensing receptor function in human colon carcinomas: promotion of E-cadherin expression and suppression of β-catenin/TCF activation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakrabarty S, Wang H, Canaff L, Hendy GN, Appelman H, Varani J. Calcium Sensing Receptor in Human Colon Carcinoma: Interaction with Ca2+ and 1,25- dihydroxyvitamin D3. Cancer Res. 2005;65:493–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bghagavathula N, Kelley EA, Reddy M, et al. Upregulation of calcium-sensing receptor and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in the regulation of growth and differentiation in colon carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1364–1371. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhagavathula N, Hanosh AW, Nerusu KC, Appelman H, Chakrabarty S, Varani J. Regulation of E-cadherin and beta-catenin by Ca2+ in colon carcinoma is dependent on calcium-sensing receptor expression and function. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1455–1462. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Augenlicht LH, editor. Cell and Molecular Biology of Colon Cancer. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Inc.; 1989. Intermediate biomarkers of increased susceptibility to cancer of the large intestine; pp. 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hebert SC, Cheng S, Geibel J. Functions and roles of the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor in the gastrointestinal tract. Cell Calcium. 2004;35:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halvorsen TB, Seim E. Degree of differentiation in colorectal adenocarcinomas: a multivariate analysis of the influence on survival. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41:532–537. doi: 10.1136/jcp.41.5.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Popat J, Matakidou A, Houlston RS. Thymidylate synthase expression and prognosis in colorectal cancer: a systemic review and meta-analysis. J clin Oncol. 2004;22:529–636. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brattain MG, Willson JKV, Long BH, Chakrabarty S, Mitomycin C. In: Drug resistance in mammalian cells. Gupta RS, editor. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1989. pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traver RD, Horikoshi T, Danenberg KD, et al. NAD(P)H; quinone oxidoreductase gene expression in human colon carcinoma cells: characterization of a mutation which modulates DT-diaphorase activity and mitomycin sensitivity. Cancer Res. 1992;52:797–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakrabarty S, Danels YJ, Long BH, Willson JKV, Brattain MG. Circumvention of deficient activation in mitomycin C resistant human colonic carcinoma cells by mitomycin C analogue BMY25282. Cancer Res. 1986;46:3456–3458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Notarbartolo M, Cervello M, Poma P, Dusonchet L, Meli M, Dalessandro N. Expresion of the IAPs in multidrug resistant tumor cells. Oncol Rep. 2004;11:133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodriguez-Nieto S, Zhivotovsky B. Role of alterations in the apoptotic machinery in sensitivity of cancer cells to treatment. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:4411–4425. doi: 10.2174/138161206779010495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sah NK, Munshi A, Hobbs M, Carter BZ, Andreeff M, Meyn RE. Effect of downregulation of survivin expression on radiosensitivity of human epidermoid carcinoma cells. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:852–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altieri DC. Survivin in apoptosis control and cell cycle regulation in cancer. Prog in Cell Cycle Res. 2003;5:447–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrario A, Rucker N, Wong S, Luna M, Gomer CJ. Survivin, a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis family, is induced by photodynamic therapy and is a target for improving treatment response. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4989–4995. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li F, Ambrosini G, Chu EY, et al. Control of apoptosis and mitotic spindle checkpoint by survivin. Nature. 1998;396:580–584. doi: 10.1038/25141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ling X, Bernacki RJ, Brattain MG, Li F. Induction of survivin expression by taxol (paclitaxel) is an early event, which is independent of taxol-mediated G2/M arrest. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15196–15203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310947200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipkin M. Preclinical and early human studies of calcium and colon cancer prevention. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;889:120–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wargovich MJ, Jimenez A, McKee K, et al. Efficacy of potential chemopreventive agents on rat colon aberrant crypt formation and progression. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1149–1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters U, Chatterjee N, Yeager M, et al. Association of genetic variants in the calcium-sensing receptor with risk of colorectal adenoma. Cancer Epidem Biomark & Prevention. 2004;13:2181–2186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marsh S. Thymidylate synthase pharmacogenetics. Invest New Drugs. 2005;23:533–537. doi: 10.1007/s10637-005-4021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danenberg PV. Pharmacogenomics of thymidylate synthase in cancer treatment. Front Biosci. 2004;9:2484–2494. doi: 10.2741/1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chu E, Callender MA, Farrell MP, Schmitz JC. Thymidylate synthase inhibitors as anticancer agents: from bench to bedside. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;52:S80–89. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0625-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose MG, Farrell MP, Schmitz JC. Thymidylate synthase: a critical target for cancer chemotherapy. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2002;1:220–229. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2002.n.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mentaverri R, Yano S, Chattopadhyay N, et al. The calcium sensing receptor is directly involved in both osteoclast differentiation and apoptosis. FASEB J. 2006;20:2562–2564. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6304fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mizobuchi M, Ogata H, Hatamura I, et al. Activation of calcium-sensing receptor accelerates apoptosis in hyperplastic parathyroid cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Z, Tandon R, Ziembicki J, et al. Role of ceramide in Ca2+-sensing receptor- induced apoptosis. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1396–1404. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500071-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin KI, Chattopadhyay N, Bai M, et al. Elevated extracellular calcium can prevent apoptosis via the calcium-sensing receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249:325–331. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vasiliou V, Ross D, Nebert DW. Update of the NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (NQO) gene family. Hum Genomics. 2006;2:329–335. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-2-5-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ross D, Kepa JK, Winski SL, Beall HD, Anwar A, Siegel D. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1): chemoprotection, bioactivation, gene regulation and genetic polymorphisms. Chem Biol Interact. 2000;129:77–97. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iskander K, Gaikwad A, Paquet M, et al. Lower induction of p53 and decreased apoptosis in NQO1-null mice lead to increased sensitivity to chemical-induced skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2054–2058. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]