Abstract

Homologous recombination is an error-free mechanism for the repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). Most DSB repair events occur by gene conversion limiting loss of heterozygosity (LOH) for markers downstream of the site of repair and restricting deleterious chromosome rearrangements. DSBs with only one end available for repair undergo strand invasion into a homologous duplex DNA, followed by replication to the chromosome end (break-induced replication [BIR]), leading to LOH for all markers downstream of the site of strand invasion. Using a transformation-based assay system, we show that most of the apparent BIR events that arise in diploid Saccharomyces cerevisiae rad51Δ mutants are due to half crossovers instead of BIR. These events lead to extensive LOH because one arm of chromosome III is deleted. This outcome is also observed in pol32Δ and pol3-ct mutants, defective for components of the DNA polymerase δ (Pol δ) complex. The half crossovers formed in Pol δ complex mutants show evidence of limited homology-dependent DNA synthesis and are partially Mus81 dependent, suggesting that strand invasion occurs and the stalled intermediate is subsequently cleaved. In contrast to rad51Δ mutants, the Pol δ complex mutants are proficient for repair of a 238-bp gap by gene conversion. Thus, the BIR defect observed for rad51 mutants is due to strand invasion failure, whereas the Pol δ complex mutants are proficient for strand invasion but unable to complete extensive tracts of recombination-initiated DNA synthesis.

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are potentially lethal lesions that can occur spontaneously during normal cell metabolism, by treatment of cells with DNA-damaging agents, or during programmed recombination processes (54). There are two major pathways to repair DSBs: nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR). NHEJ involves the religation of the two ends of the broken chromosome and can occur with high fidelity or be accompanied by a gain or loss of nucleotides at the junction (9). Repair of two-ended DSBs by HR generally occurs by gene conversion resulting from a transfer of information from the intact donor duplex to the broken chromosome (Fig. 1). HR occurs preferentially during S and G2 when a sister chromatid is available to template repair (2, 19, 22). Sister-chromatid recombination events are genetically silent, whereas gene conversion between nonsister chromatids associated with an exchange of flanking markers can result in extensive loss of heterozygosity (LOH) or chromosome rearrangements (3, 21). One-ended DSBs that arise by replication fork collapse or by erosion of uncapped telomeres are thought to repair by strand invasion into homologous duplex DNA followed by replication to the end of the chromosome, a process referred to as break-induced replication (BIR) (35). BIR appears to be suppressed at two-ended breaks, presumably because it can lead to extensive LOH if it occurs between homologues or to chromosome translocations when strand invasion initiates within dispersed repeated sequences (5, 28, 31, 50, 52, 55).

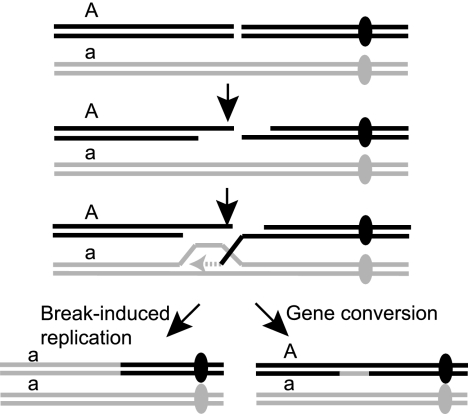

FIG. 1.

Models for gene conversion and BIR. After formation of a DSB, the ends are resected to generate 3′ single-strand DNA tails. One end undergoes Rad51-dependent strand invasion to prime DNA synthesis from the invading 3′ end templated by the donor duplex. For gene conversion by the synthesis-dependent strand annealing model, the extended invading end is displaced and can anneal to the other side of the break; completion of repair requires DNA synthesis primed from the noninvading 3′ end. For a one-ended break, or if the other side of the break lacks homology to the donor duplex, DNA synthesis proceeds to the end of the chromosome. Centromeres are shown as solid ovals and a heterozygous marker centromere distal to the site of repair as A/a.

The strand invasion step of BIR is assumed to be the same as that for gene conversion based on the requirement for the same HR proteins: Rad51, Rad52, Rad54, Rad55, and Rad57 (10). However, subsequent steps in BIR are less well defined. Recent studies of the fate of the invading end during BIR in diploid strains with polymorphic chromosome III homologues using a plasmid-based assay have shown that following strand invasion, the invading end is capable of dissociating from the initial homologous template. Following dissociation, the displaced end subsequently reinvades into the same or a different chromosome III homologue by a process termed template switching (52). One of the interesting features of the template switching events is that they occur over a region of about 10 kb downstream of the site of strand invasion and do not extend over the entire left arm of chromosome III. There are a number of possible mechanisms that could account for this apparent change in the processivity of BIR. First, it is possible that the strand invasion intermediate is cleaved by a structure-specific nuclease and once the invading strand is covalently joined to one of the template strands, the strand invasion process is irreversible. Recent studies of Schizosaccharomyces pombe have shown an essential role for Mus81, a structure-specific nuclease, in resolution of sister chromatid recombination intermediates during repair of collapsed replication forks (48). Another possibility is that there could be a switch between a translesion DNA polymerase and a highly processive DNA polymerase during BIR. The translesion polymerases in budding yeast, polymerase ζ (Pol ζ) and Pol η, are encoded by REV3-REV7 and RAD30, respectively (34, 40, 43). Deletion of REV3 has been shown to increase the fidelity of DNA synthesis associated with HR but has no effect on the overall frequency of DSB-induced HR (16). Deletion of POLη in chicken DT40 cells reduces the frequency of DSB-induced gene conversion, and human POL η has been shown to extend the invading 3′ end of D-loop intermediates in vitro (23, 36). However, this same preference for Pol η is not found for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Instead, DNA synthesis during meiotic and mitotic recombination appears to be carried out by Pol δ, one of the three nuclear replicative polymerases, which normally functions with Pol α in Okazaki fragment synthesis (13, 32, 33, 44). Pol ɛ is thought to be the primary leading-strand polymerase (47), but in the absence of the Pol ɛ catalytic domain, Pol δ is presumed to carry out leading-strand synthesis (24). Recent studies by Lydeard et al. (30) have shown a requirement for the lagging-strand polymerases, Pol δ and Pol α, to form the initial primer extension product during BIR, and Pol ɛ is required to complete replication to the end of the chromosome. In contrast, repair of DSBs by gene conversion does not require Pol α, and there appears to be functional redundancy between Pol δ and Pol ɛ (56).

To address the roles of Mus81, Pol δ, and Pol η in BIR and in particular template switching, we used the transformation-based BIR assay with diploids with polymorphic chromosome III homologues. Because the transformation assay can only be used with strains with viable mutations of replication factors, we used a null allele of POL32, encoding a nonessential subunit of the Pol δ complex (14), and a point mutation in the gene encoding the essential catalytic subunit, POL3. The pol3-ct allele results in a truncation removing the last four amino acids of the Pol3 protein; the C-terminal region of Pol3 is implicated in interaction with the other essential subunit of the Pol δ complex, Pol31 (15, 49). The interesting feature of the pol3-ct allele is that it decreases the length of gene conversion tracts during mitotic and meiotic recombination, presumably by affecting the processivity of Pol δ, but confers no apparent defect in normal DNA synthesis (32, 33). Because BIR requires more-extensive tracts of DNA synthesis than gene conversion, we expected the pol3-ct mutant to exhibit a BIR defect. We found that in the absence of a fully functional Pol δ complex, chromosome fragment (CF) formation proceeds by a half-crossover mechanism associated with loss of the template chromosome, an event with potentially catastrophic consequences (6, 57). This was also found to occur in rad51 mutants, suggesting nonreciprocal translocations arise by failure to undergo strand invasion or because replication following strand invasion is inefficient. In contrast to rad51 mutants, the Pol δ complex mutants are proficient for repair of a 238-bp gap by gene conversion and fully resistant to ionizing radiation, suggesting there is a unique requirement for Pol δ to complete BIR. Consistent with studies of gene conversion in S. cerevisiae (33), we found no role for Pol η in BIR or the process of template switching.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media, growth conditions, and genetic methods.

Rich medium (yeast extract-peptone-dextrose [YPD]), synthetic dropout and synthetic complete medium (SC) lacking the appropriate amino acids or nucleic acid bases, sporulation medium, and genetic methods were as described previously (51). Transformation of yeast cells was performed by the lithium acetate method (20). Mating tests were performed by patching independent Ura+ transformants onto YPD plates, replica plating to lawns of MATa and MATα tester strains to allow mating for 6 h, and then replica plating to synthetic dropout selection plates.

Yeast strains.

The diploid yeast strain with chromosome III markers was made by crossing haploid strains MW16 (MATα trp1 arg4 tyr7 ade6 ura3) and MD249 (MATa leu2-bst ade6 ura3 cha1::hphMX6) (38, 58). The pol3-ct diploid used was previously described and is isogenic to diploids derived from MW16 and MD249 (32). mus81Δ, pol32Δ, rad30Δ, and rad51Δ derivatives were constructed by deleting from the haploid MW16 and MD249 strains either MUS81, POL32, RAD30, or RAD51 using a PCR fragment containing homologous 5′- and 3′-flanking sequences from the BY4742 (MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0) deletion strain collection containing either mus81::KanMX4, pol32::KanMX4, rad30::KanMX4, or rad51::KanMX4, resulting in the integration of the KanMX4 marker and the loss of the wild-type allele. The mus81Δ pol3-ct double mutant was made by replacement of the MUS81 locus with the KanMX4 marker in the haploid strains LMP2 and LMP6 containing the pol3-ct allele. The haploid strains were then crossed, and diploids were selected for on SC medium lacking Leu and Trp. Strains LSY205 (MATa suc2-437 lys2-802) and LSY206 (MATα lys2-802) were used for mating-type tests, or the MAT locus was scored by PCR (17).

BIR assay.

The chromosome fragmentation vector (CFV), CFV/D8B-tg (CFV1), containing a 5.2-kb insert from the left arm of chromosome III (SGD coordinates 96821 to 102096), and CFV2, containing a 3.3-kb BglII fragment from chromosome III (coordinates 103535 to 106833), were described previously (10, 52). A 0.1- to 1-μg amount of the CFV, digested with SnaBI, was used to transform competent yeast cells, selecting for Ura+ transformants. Larger amounts of DNA were necessary to recover transformants from the rad51 mutant. Because some Ura+ transformants are due to NHEJ of the vector, resulting in an unstable plasmid, Ura+ transformants were struck onto nonselective YPD medium and then replica plated to SC medium lacking Ura to determine the stability of the Ura+ phenotype. The frequency of BIR presented in Fig. 2 is the number of mitotically stable Ura+ transformants per microgram of linearized DNA transformed divided by the number of Ura+ transformants per microgram of circular plasmid DNA transformed. The mean BIR frequencies (with standard deviations) presented are from at least three independent transformations of each strain. Statistical analyses were performed using an unpaired t test. DNA analysis of stable Ura+ transformants to score restriction site markers was as described previously (52). Statistical significance for the loss of chromosome III during CF formation was performed using a chi-square test.

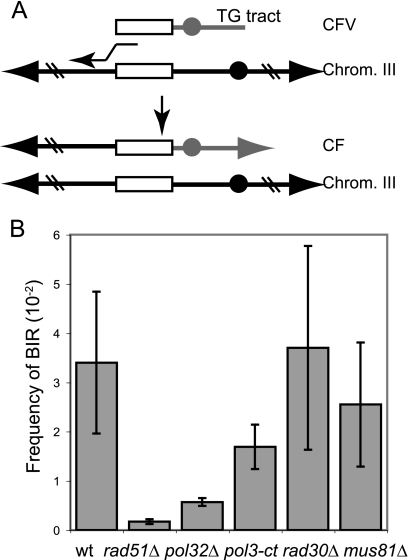

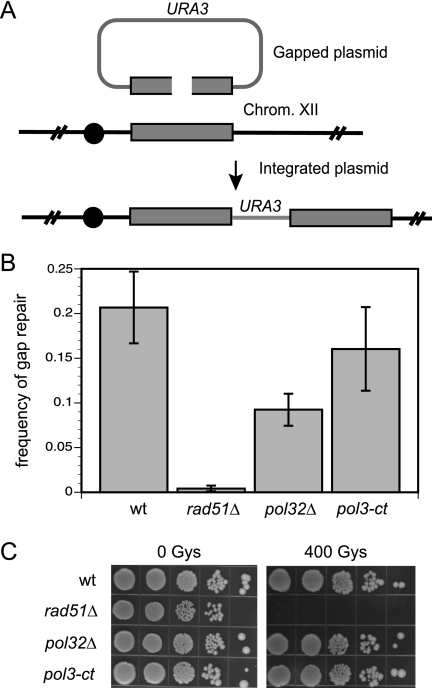

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the chromosome fragmentation assay and frequency of BIR. (A) Following transformation into competent yeast cells, the linear CFV undergoes de novo telomere addition to the TG tract at one end of the vector, and the other end invades the endogenous chromosomal locus duplicating sequences from the region of homology between the vector and the native chromosome to the telomere. The region of homology is shown as a white rectangle; centromeres are shown as solid circles and telomeres as arrowheads. (B) Frequency of BIR. Each frequency is measured as the number of stable Ura+ transformants per microgram of cut CFV1 divided by the number of Ura+ transformants per microgram with uncut DNA transformed. wt, wild type.

Plasmid DNA gap repair assay.

The nonreplicating gap repair plasmid, pSB101, was described previously (4). Plasmid pSB101 was digested with BspEI and EcoNI, and the linear DNA was gel purified. Transformation was performed by the lithium acetate transformation method with 100 ng of gapped plasmid (gap repair substrate) or 100 ng of uncut replicating plasmid pSB110 (transformation efficiency control). The transformed cells were diluted and plated on SC medium lacking Ura. The colonies were counted after incubation at 30°C for 2 to 3 days. The frequency of gap repair is the number of Ura+ transformants per microgram of linearized DNA transformed divided by the number of Ura+ transformants per microgram of circular plasmid DNA transformed. Statistical significance was calculated using an unpaired t test.

γ-irradiation sensitivity tests.

Cells were grown in liquid YPD medium at 30°C to exponential phase. The cultures were serially diluted, and aliquots of each dilution were spotted onto YPD plates. The plates were irradiated in a Gammacell-220 irradiator containing 60Co and incubated at 30°C for 3 days.

RESULTS

The polymerase δ complex is required for efficient BIR.

To evaluate the role of the Pol δ complex, Pol η, and Mus81 in BIR, we used the transformation-based assay in conjunction with diploid strains containing restriction site polymorphisms on the left arm of chromosome III and homozygous mutations of the relevant genes (Fig. 2A) (10, 52). The CFV contains the URA3 selectable marker, SUP11, CEN4, an autonomously replicating sequence, a tract of (G1-3T)n to provide a site for telomere addition, and a unique DNA segment from the left arm of chromosome III. After transformation of yeast with the linearized CFV, a CF is generated by de novo telomere addition at one end of the vector and recombination-dependent replication of 97 kb of chromosomal sequences at the other end of the vector (Fig. 2A). The rad51Δ diploid was used as a control for a mutant defective for BIR (10). The number of transformants with a stable Ura+ phenotype after being challenged with nonselective growth conditions was normalized for transformation efficiency of each strain, measured by transformation with uncut CFV. In the case of the rad51Δ strain, 25% of the stable Ura+ colonies were due to reversion or conversion of the chromosomal ura3 gene, and the BIR frequency was adjusted accordingly. The pol32Δ diploid exhibited a sixfold-reduced frequency of BIR compared with that of the wild type (P = 0.01), but there was not a complete dependence on POL32 for CF formation (Fig. 2B). The frequency of BIR was reduced by 20-fold in the rad51Δ diploid compared with that in the wild-type diploid (P = 0.007) and was threefold lower than that of the pol32Δ mutant (P = 0.002), consistent with results in previous studies (30). The frequency of BIR was reduced by only twofold in the pol3-ct diploid (P = 0.02). We had expected a greater reduction in BIR based on previous studies showing reduced meiotic and mitotic conversion tract lengths in this mutant (32, 33); however, as described below, the events recovered in the pol3-ct strain were formed by a mechanism different from CF formation in the wild-type diploid. There was no significant decrease in the frequency of BIR in the rad30Δ and mus81Δ mutants.

In the absence of a fully functional Pol δ complex or RAD51, chromosome fragments form by half crossovers.

To determine whether the Pol δ mutants undergo DNA synthesis during CF formation, we made use of the restriction site polymorphisms present on the chromosome III homologues (Fig. 3). These allow us to track which chromosomal template was used for CF formation, giving insight into how replication progresses during BIR. We previously showed that in wild-type cells, the invading strand that was extended by DNA synthesis could dissociate and invade into the other parental homologue, creating a chimeric CF (52).

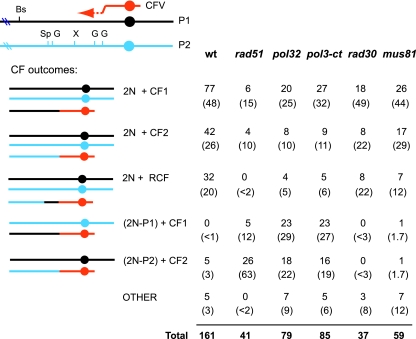

FIG. 3.

CF formation proceeds by a half crossover in polymerase δ and rad51 mutants. A schematic representation of the restriction site polymorphisms carried on the chromosome III homologues and the classes of CFs recovered is shown. RCF refers to the events formed by template switching to form chimeric CFs. Coordinates of the markers scored are 91358 (Bs, BstEII), 96182 (Sp, SpeI), 96821 (G, BglII), 99611 (X, XhoI), 102096 (G, BglII), and 103535 (G, BglII). The numbers of each class of event in the wild-type and mutant strains are shown; the numbers on the second line, in parentheses, are percentages of each class.

Total genomic DNA from stable Ura+ transformants was analyzed by restriction endonuclease digestion and Southern blotting to determine the composition of the CF. We then selected for loss of the CF by plating cells on medium containing 5-fluoroorotic acid (which selects against Ura+ cells) and repeated the genomic DNA analysis to confirm that novel restriction fragments were linked to the CF. In the wild-type diploid, 32 of 161 Ura+ transformants showed template switching, referred to as recombinant CFs (RCFs) (Fig. 3) (52). Of the 129 CFs that had not undergone template switching, 5 were associated with the loss of a chromosome III homologue and the sequences acquired by the CF were derived from the lost copy of chromosome III. These events are most simply explained by a crossover between the linear fragment and the chromosome III homologue invaded, similar to the mechanism proposed for gene targeting except that only one crossover is required. This type of recombination event maintains disomy for sequence distal to the site of strand invasion but results in monosomy for most of chromosome III. These events will be referred to as half crossovers to distinguish them from BIR events, which maintain both copies of chromosome III in addition to the CF. It should be noted, however, that some events that maintain both copies of chromosome III could be formed by a half crossover in G2 followed by segregation of two intact copies of chromosome III and the CF to the same daughter cell (see Discussion). In five of the samples, one or more chromosomal sites had become homozygous, referred to as “other”.

In both the pol32Δ and pol3-ct diploids, we found that formation of CFs was frequently by a half-crossover mechanism (Fig. 3). Of 79 CFs analyzed from the pol32Δ diploid, 41 (51%) were associated with loss of one of the chromosome III homologues. Of these, 23 acquired sequences from homologue P1; the other 18 acquired sequences from homologue P2. The same pattern was observed for the pol3-ct diploid. Of 85 CFs analyzed, 39 (46%) were associated with chromosome loss. Of these, 23 CFs were formed by acquisition of sequence from chromosome III homologue P1, while 16 acquired sequence from P2 (Fig. 3). Like the Pol δ complex mutants, the rad51Δ diploids also showed elevated rates of chromosome loss associated with CF formation. In this case, of 41 CFs analyzed 31 (75%) were associated with chromosome loss. Chromosome loss in the rad51Δ, pol3-ct, and pol32Δ mutant diploids was significantly higher than that in the wild-type diploid (P < 0.0001 for all mutants tested). This suggests the CFs formed in the mutants are not the result of a true BIR event and instead form by a half-crossover mechanism.

Diploids are heterozygous for the mating type (MAT) locus on the right arm of chromosome III and exhibit a nonmating phenotype. Chromosome III loss, or homozygosis of the MAT locus, results in expression of only MATa or MATα information and can be detected by the ability of cells to mate with haploid test strains. To confirm loss of one copy of chromosome III in the rad51Δ, pol32Δ, and pol3-ct diploids transformed with CFV1, mating tests were performed on independent Ura+ transformants. For all three mutants, >50% of the transformants exhibited a mating phenotype, compared with 13% for the wild-type diploid (data not shown). To ensure that chromosome loss was not due to the transformation process, we also tested the mating phenotype of Ura+ transformants derived from uncut CFV1 in the pol32Δ and pol3-ct diploids. Only 1/93 pol3-ct transformants and 1/64 pol32Δ transformants were mating proficient. Thus, chromosome loss is associated with CF formation and is not induced by transformation.

Analysis of CFs formed in the rad30Δ (Pol η) and mus81Δ diploids revealed that most were formed by BIR (Fig. 3). Of 37 CFs analyzed from the rad30Δ diploid, 8 RCFs were identified; of these, three were associated with loss of one of the chromosome III homologues. Three other events were associated with conversion of chromosomal markers, and one of these also had an RCF. Because the frequency of template switching events and the distribution of events were not significantly different from those for the wild type, we conclude Pol η is not responsible for the change in processivity during BIR. Similarly, the frequency and distribution of RCFs recovered from the mus81Δ diploid were not significantly different from those for the wild-type strain (Fig. 3 and data not shown).

Rare template switching in pol32Δ and pol3-ct diploids.

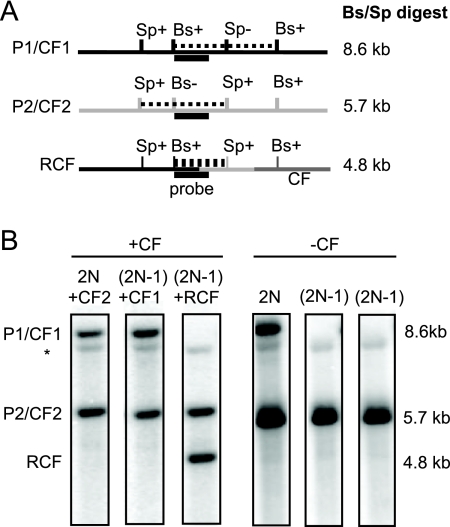

The decrease in the frequency of BIR and formation of half crossovers in the rad51Δ, pol3-ct, and pol32Δ mutant diploids suggests strand invasion or that DNA synthesis primed from the invading end is defective. While strand invasion is known to be severely impaired in the rad51Δ diploid, we assume strand invasion occurs in the pol3-ct and pol32Δ diploids but DNA synthesis is attenuated. If a short tract of DNA was synthesized from the invading end and displacement and reinvasion occurred, we would expect to observe low-frequency template switching in the Pol δ-defective mutants. Of the 79 CFs screened from the pol32Δ mutant, 4 were formed by template switching and all were associated with loss of the chromosome III homologue that was used for the second-strand invasion (Fig. 3). For the RCF shown in Fig. 4, the invading end would have to be extended by at least 500 nucleotides to create the novel restriction fragment diagnostic of template switching. Similarly, five RCFs were recovered from the pol3-ct mutant, and three of them were associated with loss of one of the chromosome III homologues. For one of the events observed in the pol3-ct mutant, at least 3.4 kb of DNA would need to be synthesized to produce the RCF. Therefore, short tracts of DNA synthesis occur in the pol32Δ and pol3-ct mutants prior to crossover formation. We also noted several events with chromosome rearrangements in the Pol δ complex mutants. This class included events with conversion of one of the chromosomal markers and one case of a reciprocal exchange between markers in the pol32Δ mutant. One event recovered from the pol3-ct mutant could have been due to a template switch event following a reciprocal exchange between the BstEII and SpeI markers or could have been due to copying of P2 followed by a reciprocal exchange between the homologues. Analysis of 41 CFs from the rad51Δ diploid failed to reveal any evidence of template switching or alterations of the chromosome III markers consistent with strand invasion failure.

FIG. 4.

Physical analysis of CFs from the pol32Δ mutant, showing template switching prior to half-crossover formation. (A) Schematic representation of the region of chromosome III showing the heterozygous BstEII (Bs) and SpeI (Sp) sites and the expected restriction fragments for P1, P2, and one of the two possible RCFs. Note that CFs that copy from only P1 or P2 will have the same-size restriction fragments as P1 or P2, respectively. (B) Southern blot showing representative 2N + CF, (2N−1) + CF, and (2N−1) + RCF classes in the left panel; the panel on the right shows the DNA analysis after selection for loss of the CF by plating cells on medium containing 5-fluoroorotic acid.

MUS81-dependent half crossovers.

Template switching in the pol3-ct and pol32Δ mutants provides evidence that strand invasion and limited DNA synthesis occur, but due to the defect in DNA synthesis, we imagine the stalled intermediate is then cleaved by an endonuclease to generate a crossover (Fig. 5). The Mus81-Mms4 heterodimeric endonuclease cleaves a variety of branched DNA structures in vitro, including strand invasion intermediates (45). We constructed a diploid mus81Δ pol3-ct double mutant to determine whether the half crossovers are the result of Mus81 cleavage of the strand invasion intermediate. Although the frequency of Ura+ transformants for the mus81Δ pol3-ct double mutant was not significantly reduced from that for the pol3-ct single mutant, there was a significant reduction in the number of chromosome loss events (P = 0.0002) (Table 1).

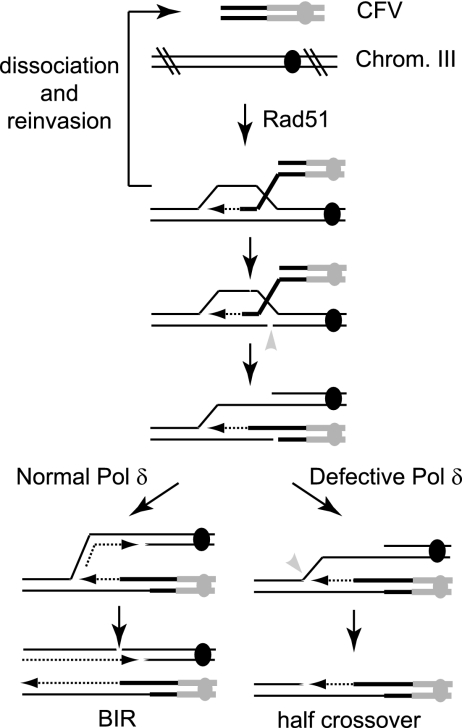

FIG. 5.

Model for CF formation in the Pol δ mutants. Following strand invasion of wild-type (RAD51) cells, the 3′ invading end is extended by DNA synthesis. The invading end can dissociate and undergo strand invasion and extension from the 3′ end again (template switching). The strand invasion intermediate is cleaved and one strand from the CFV ligated to the nicked strand of the donor duplex. This transition prevents dissociation (and template switching) of the invading end and is permissive for assembly of the other replication components to initiate processive replication to the chromosome end. In this case, both chromosome III homologues remain intact. Following strand invasion in Pol δ mutant diploids, the D-loop is cleaved as described above, but in the absence of extensive synthesis from the invading strand and/or because initiation of lagging-strand synthesis is delayed, a second cleavage event occurs, generating a half crossover. This results in the formation of a CF and broken chromosome III homologue, which is subsequently lost.

TABLE 1.

Chromosome loss in pol3-ct and mus81Δ diploids

| Relevant genotype | % Chromosome III loss | Total no. of eventsa |

|---|---|---|

| MUS81 POL3 | 7.7 | 286 |

| mus81Δ POL3 | 6.9 | 158 |

| MUS81 pol3-ct | 53.9 | 241 |

| mus81Δ pol3-ct | 24 | 50 |

The Pol δ complex mutants are proficient for plasmid gap repair and survival with ionizing radiation.

To determine whether the defect in BIR seen in the pol32Δ and pol3-ct mutants was due to a general recombination defect or was specific to the extensive tracts of DNA synthesis associated with BIR, the frequency of plasmid double-strand gap repair was determined. In the plasmid gap repair assay, Ura+ transformants result from homology-dependent repair of a 238-bp gap within the MET17 open reading frame followed by integration of the plasmid at the chromosomal MET17 locus (Fig. 6A). Plasmid gap repair occurs with a frequency of 20.7 × 10−2 in the MW16/MD249 background. As expected, the rad51Δ mutant diploid showed a significant decrease in the frequency of plasmid gap repair (0.42 × 10−2; P = 0.001), while the pol32Δ mutant diploid had only a twofold (P = 0.01) decrease, and there was no significant decrease for the pol3-ct diploid (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that the defect observed for the Pol δ mutants in the BIR assay is specific for BIR and is not due to a general recombination defect or a defect in cellular uptake of linear DNA during transformation.

FIG. 6.

Pol δ mutants are proficient for limited DNA synthesis following strand invasion. (A) Schematic representation of the gap repair assay. Following transformation of a gapped plasmid into competent yeast, both ends invade the endogenous chromosomal locus. Repair has to occur by integration to yield a stable Ura+ transformant. Repair by integration leads to duplication of sequences from the region of homology between the vector and the native chromosome. (B) Frequency of repair of a gapped plasmid substrate. Frequencies are measured as the number of Ura+ transformants per 100 ng of cut DNA divided by the number of transformants per 100 ng uncut DNA transformed. (C) Tenfold serial dilutions of each strain were spotted onto YPD plates and left unirradiated or were irradiated with 400 Gy.

To confirm this result, we tested wild-type and mutant strains for their ability to repair DNA damage caused by ionizing radiation. It is known that mutation of genes in the RAD52 epistasis group confers high sensitivity to ionizing radiation due to defects in homology-dependent repair (54). To determine whether the same was true for the Pol δ mutants, diploid strains were grown to exponential phase and then exposed to 400 Grays of ionizing radiation. As expected, the rad51Δ mutant was highly sensitive to ionizing radiation while the pol32Δ and pol3-ct mutants were resistant (Fig. 6C). These results confirm that the BIR defect observed in the Pol δ mutants is specific for the homology-dependent repair that requires long stretches of DNA synthesis.

DISCUSSION

DNA synthesis is an essential step in homologous recombination to replace nucleotides lost by excision of sequence during the repair process. Homology-dependent repair of DSBs initiates from single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) generated by 5′-3′ resection of the DNA ends (25). Rad51 binds to the resulting ssDNA tails to initiate pairing and strand invasion with homologous duplex DNA (25). The 3′ end from the broken chromosome is used to prime leading-strand DNA synthesis templated by the donor duplex. For gene conversion by the synthesis-dependent strand annealing model (12, 42), the invading strand that has been extended by DNA synthesis is displaced and anneals to complementary sequence exposed by 5′-3′ resection of the other side of the break (Fig. 1). Thus, only short tracts of DNA synthesis are required for repair of DSBs by gene conversion. DSBs that present only one end for repair, such as those produced by unprotected telomeres, undergo strand invasion and replication to the end of the chromosome (BIR). Because this process can lead to the amplification of the 6.7-kb subtelomeric Y′ repeats, the tracts of DNA synthesis are likely to be considerably longer than those for gene conversion (29, 35). BIR can also occur at two-ended DSBs that have only one end with homology to a donor sequence and initiate extensive tracts (>100 kb) of DNA synthesis (31, 41). BIR from a two-ended DSB can result in extensive LOH or chromosome rearrangements if it occurs between chromosome homologues or dispersed repeats, a common phenotype of tumor cell lines (6, 28, 52, 53, 55, 57). Furthermore, aging yeast cells more frequently repair spontaneous damage by a mechanism resulting in LOH than young cells, and it has been suggested this mechanism is BIR (37). Thus, regulation of BIR at two-ended breaks is important for maintaining genome integrity. One proposed mechanism to control BIR is to delay strand invasion or DNA synthesis from the invading end at a one-ended break until the cell senses the absence of the second end; this implies coordination of the two ends of the break at an early step (31). We recently suggested that another mechanism to control extensive replication at two-ended DSBs is the ability of the invading end to displace from the template DNA. Assuming the second end of a DSB is available to capture the displaced invading end, this terminates replication, leading to limited LOH (52). When the second end is absent, the displaced end invades the same or a different homologous template, a process referred to as template switching. Because template switching is limited to about 10 kb downstream of the site of strand invasion, there appears to be a change in the nature of the strand invasion intermediate or mode of DNA replication during BIR. This study was initiated to gain insight into the replication factors that extend the invading 3′ end during BIR and how template switching is regulated.

CF formation proceeds by a half-crossover mechanism in mutants defective for Pol δ.

In the transformation-based BIR assay, we found a sixfold decrease in the recovery of stable Ura+ transformants in the pol32Δ mutant; however, the CFs formed were frequently (∼50%) associated with a loss of the chromosome that was used as the donor for strand invasion (Fig. 3). Thus, in the pol32Δ mutant, CF formation proceeds by a half-crossover mechanism and not by BIR. This process leads to a nonreciprocal transfer of information from the donor to the recipient, in this case from chromosome III to the CFV, leaving the cell with a broken chromosome III arm that is subsequently degraded. The donor chromosome is unchanged in true BIR events. These events were detected at a lower frequency in wild-type cells and are mechanistically similar to the processing of ends during gene targeting (26, 46). Using a different assay system for BIR, Deem et al. (11) also showed generation of half-crossover events in the pol32Δ mutant, though the frequency of events was lower than that reported here and they found a more-severe defect in gene conversion than BIR in the pol32Δ mutant. POL32 was recently identified in a screen of diploid yeast for mutants with elevated rates of spontaneous LOH (1). Most of the LOH events observed in the pol32Δ mutant were due to reciprocal recombination, presumably because these initiate at two-ended DSBs or ssDNA gaps or because the BIR pathway is inefficient. The increased rate of spontaneous recombination is most likely due to defects in DNA synthesis, resulting in more initiating lesions. Although the frequency of CF formation was only modestly decreased in the pol3-ct mutant, the events recovered were also associated with high-frequency chromosome loss, suggesting strand invasion is proficient and the defect occurs at a subsequent step (Fig. 3). In the case of the pol32Δ mutant, it appears that the defect is at an earlier step than in the case of the pol3-ct mutant because the recovery of CFs is lower. We consider it unlikely for strand invasion to be defective in the pol32Δ mutant and assume the defect is due to an inability to efficiently extend the 3′ end of the invading strand. These results are consistent with those in previous studies showing an important role for Pol δ in the extension of the invading strand during gene conversion and BIR (30, 32, 33). However, our data do not exclude the possibility that another polymerase extends the invading end and the BIR failure of the Pol δ mutants is due to an inability to initiate lagging-strand synthesis. We did not find any role for Pol η in these studies, suggesting Pol δ is required for both the initial stage of DNA synthesis and the transition to more processive DNA synthesis.

Short tracts of DNA synthesis in Pol δ complex mutants.

In the studies of Lydeard et al. (30), DNA synthesis of ∼250 nucleotides from the invading end was undetectable in the pol32Δ mutant; however, mating-type switching, which requires at least 700 bp of DNA synthesis, appeared unaffected. These results suggest Pol32 is required specifically to extend one-ended strand invasion intermediates, a conclusion bolstered by the observation that telomerase-independent survivors were absent from the pol32Δ mutant (30). To address whether any DNA synthesis occurs during CF formation in the pol32Δ mutant, we made use of the polymorphic markers on chromosome III. If template switching occurs, we assume DNA was synthesized from the invading end prior to dissociation and invasion into the other chromosome homologue. In both pol32Δ and pol3-ct mutants, we obtained evidence of template switching; in most cases the chimeric CF was found in a 2N−1 diploid, indicating a half crossover occurred after the second strand invasion event (Fig. 4). These results show DNA synthesis from one-ended strand invasion intermediates is not eliminated by the pol32Δ mutation, but the frequency of these events is greatly reduced. This low level of DNA synthesis may be undetectable by physical assays (30). Because the recovery of CFs is higher in the pol3-ct mutant than in the pol32Δ mutant, we suggest strand invasion occurs in both mutants but DNA synthesis is initiated less frequently in the pol32Δ mutant, destabilizing the strand invasion intermediate. The plasmid gap repair assay requires synthesis of at least 238 bp. In this assay, only a twofold decrease in the frequency of gap repair and integration was found in the pol32Δ mutant compared with results for the wild type and no defect was found for the pol3-ct mutant (Fig. 6). Furthermore, the pol32Δ and pol3-ct mutants exhibit no sensitivity to ionizing radiation, even at a dose that generates about 40 DSBs per diploid genome. These results suggest that strand invasion occurs in the Pol δ complex mutants and a short tract of DNA synthesis ensues, followed by dissociation of the invading strand; this is sufficient for repair of two-ended DSBs by gene conversion. For successful BIR, more extensive DNA synthesis is required, presumably coupled to assembly of the full replisome. In order to replicate 100 kb, we imagine the replicative helicase (MCM complex) would need to be recruited, as well as all the components of leading- and lagging-strand DNA synthesis. The MCM complex is not required for the DNA synthesis associated with gene conversion (56). Whether replisome assembly needs to occur before DNA synthesis from a one-ended break initiates or occurs after gene conversion fails is an open question.

Models for half-crossover formation.

We suggest that following introduction of the CFV into the cell, strand invasion occurs, followed by a minimal amount of DNA synthesis. The invading strand may dissociate and undergo a second strand invasion event, giving rise to template switching. For replication of the entire chromosome arm (BIR), we suggest the D-loop intermediate is cleaved and one strand of the vector becomes covalently joined to one strand of the donor duplex. This would prevent dissociation of the invading strand and create a structure for assembly of the full replisome, leading to processive DNA synthesis. In the Pol δ complex mutants, we suggest that extension of sequence from the invading end is inefficient and/or there is a defect in recruitment of lagging-strand replication factors. The D-loop would then be susceptible to a second cleavage event, so that sequence distal to the strand invasion intermediate would be transferred to the CFV, leaving a broken chromosome III arm that is subsequently degraded (Fig. 5). The number of chromosome loss events in the pol3-ct diploid was reduced to 24% by mutation of MUS81, suggesting at least half of the strand invasion intermediates are cleaved by the Mus81-Mms4 nuclease (Table 1). The residual events could be due to cleavage by other nucleases, such as Rad1-Rad10 or Yen1 (18, 27), or could be formed by single-strand annealing (see below).

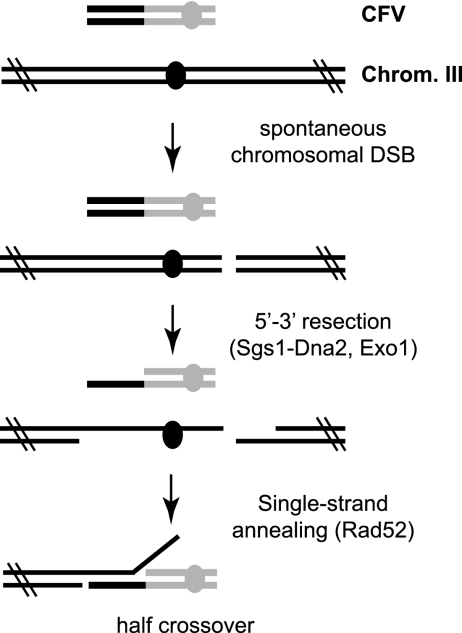

Because rad51Δ mutants are defective for strand invasion, we propose a different mechanism for half crossovers in this background. In the rad51Δ strains, we propose that following transformation of the linear CFV into the cell, the CFV fuses with a fragment of chromosome III. Rare chromosome breaks will persist in the rad51Δ mutant because of the strand invasion defect. If a random DSB occurs to the right of the region of homology shared with the CFV (this would include all of the right arm of chromosome III) and the ends of the DSB and the CFV are processed, leading to the formation of 3′ ssDNA tails, the complementary ssDNA exposed could then be annealed, leading to the formation of a full-length CF and a broken chromosome III arm (Fig. 7). This likely proceeds by RAD52-dependent single-strand annealing, a process known to be independent of RAD51 (46). Notably, CFs are not formed in rad52Δ mutants, and the frequency of CF formation in the rad51 mutant is reduced by mutation of RAD59, consistent with the idea that this rare class of RAD51-independent events forms by single-strand annealing (10). Coic et al. (7) estimated the probability of a single DSB on the right arm of chromosome III to be 2 × 10−3. Based on the transformation efficiency of the rad51Δ mutants using a replicating plasmid, we estimate ∼ 5 × 104 cells take up the linear CFV; thus, the number of spontaneous breaks is sufficient to account for generation of the rare Ura+ transformants by single-strand annealing. The other prediction from this model is that the number of Ura+ transformants recovered from the rad51Δ mutant should be decreased by mutations that eliminate resection. Although CFs are still recovered in rad51Δ rad50Δ mutants, the rad50Δ mutation decreases the initiation of resection and not the extensive resection suggested by the model (10, 39, 59). Zhu et al. (59) found that extensive resection is reduced by mutation of SGS1, and consistent with this, we observed a 20-fold decrease in the recovery of stable Ura+ transformants in the rad51Δ sgs1Δ double mutant compared with that in the rad51Δ single mutant (data not shown). The sgs1Δ mutation by itself does not decrease BIR (data not shown). Deem et al. did not recover half-crossover events in rad51Δ mutants using their BIR assay (11). One possible explanation is that in the transformation BIR assay, we are able to select rare, low-frequency events, whereas the survival rate of the rad51 mutant is very high in the homothallic switching endonuclease-induced break system, but most of the survivors lose the broken chromosome.

FIG. 7.

Model for CF formation in the rad51Δ mutant. In rad51Δ diploids, following formation of a random chromosomal break, the break end and CFV are processed by nucleases. This results in complementary ssDNA tailed duplexes that are subsequently annealed by Rad52, leading to the formation of a CF and broken chromosome III (Chrom. III) homologue that is subsequently lost.

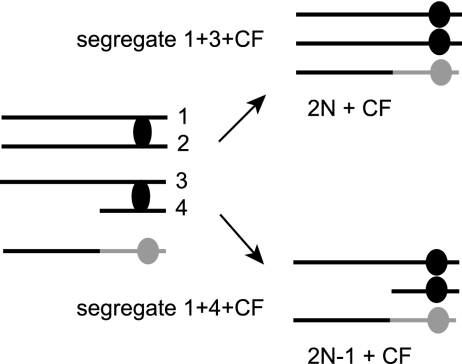

Though 25 to 50% of the Ura+ transformants recovered from rad51Δ, pol32Δ, and pol3-ct diploids retained both chromosome III homologues, these are unlikely to be true BIR events. We do not know in which phase of the cell cycle the half crossovers occur. If strand invasion initiates during the S or G2 phase of the cell cycle, by random segregation the broken chromosome arm should segregate with the CF 50% of the time (Fig. 8). About 50% of the events observed in pol32Δ and pol3-ct diploids are due to segregation of the CF with the broken chromosome III (2N−1 events). The elevated rates of 2N−1 plus CF events observed in the rad51Δ diploid may be caused by half-crossover formation before the chromosomes have replicated or by replication of a broken chromosome followed by G2 half crossover. In diploid cells, we are able to recover events in which the CF formed by a half-crossover segregates with the intact or broken sister chromatid. In haploids, only the half-crossover events in which the CF segregates with an intact sister chromatid would be viable. CFs are recovered at a low frequency from the haploid rad51 mutant, and these are most likely due to a half crossover in which the CF segregates with the intact sister chromatid, appearing as a BIR event. We suggest many of the LOH events previously described for rad51Δ mutants are due to half crossovers and not BIR (8, 55).

FIG. 8.

Model for 2N + CF genotype when CF formation proceeds by a half crossover. Formation of a half crossover in G2 results in a CF and broken chromatid. Following mitotic division, chromatids 1 and 3 can segregate with the CF while chromatid 2 and the broken chromatid 4 cosegregate. Following selection for uracil prototrophy, only the daughter with the CFV survives, leading to a 2N + CF genotype. If chromatid 1 and the broken chromatid cosegregate with the CF, then selection for uracil prototrophy allows only for growth of a 2N−1 + CF colony. Black corresponds to chromosome III sequences; gray corresponds to the CFV.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Maloisel for yeast strains and W. K. Holloman for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM041784 and GM054099).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 January 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen, M. P., Z. W. Nelson, E. D. Hetrick, and D. E. Gottschling. 2008. A genetic screen for increased loss of heterozygosity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1791179-1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aylon, Y., B. Liefshitz, and M. Kupiec. 2004. The CDK regulates repair of double-strand breaks by homologous recombination during the cell cycle. EMBO J. 234868-4875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbera, M. A., and T. D. Petes. 2006. Selection and analysis of spontaneous reciprocal mitotic cross-overs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10312819-12824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartsch, S., L. E. Kang, and L. S. Symington. 2000. RAD51 is required for the repair of plasmid double-stranded DNA gaps from either plasmid or chromosomal templates. Mol. Cell. Biol. 201194-1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosco, G., and J. E. Haber. 1998. Chromosome break-induced DNA replication leads to nonreciprocal translocations and telomere capture. Genetics 1501037-1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, M. A. 1997. Tumor suppressor genes and human cancer. Adv. Genet. 3645-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coic, E., T. Feldman, A. S. Landman, and J. E. Haber. 2008. Mechanisms of Rad52-independent spontaneous and UV-induced mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 179199-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daigaku, Y., K. Endo, E. Watanabe, T. Ono, and K. Yamamoto. 2004. Loss of heterozygosity and DNA damage repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. 556183-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daley, J. M., P. L. Palmbos, D. Wu, and T. E. Wilson. 2005. Nonhomologous end joining in yeast. Annu. Rev. Genet. 39431-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis, A. P., and L. S. Symington. 2004. RAD51-dependent break-induced replication in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 242344-2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deem, A., K. Barker, K. Vanhulle, B. Downing, A. Vayl, and A. Malkova. 2008. Defective break-induced replication leads to half-crossovers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1791845-1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferguson, D. O., and W. K. Holloman. 1996. Recombinational repair of gaps in DNA is asymmetric in Ustilago maydis and can be explained by a migrating D-loop model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 935419-5424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg, P., and P. M. Burgers. 2005. DNA polymerases that propagate the eukaryotic DNA replication fork. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 40115-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerik, K. J., X. Li, A. Pautz, and P. M. Burgers. 1998. Characterization of the two small subunits of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase delta. J. Biol. Chem. 27319747-19755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giot, L., R. Chanet, M. Simon, C. Facca, and G. Faye. 1997. Involvement of the yeast DNA polymerase delta in DNA repair in vivo. Genetics 1461239-1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holbeck, S. L., and J. N. Strathern. 1997. A role for REV3 in mutagenesis during double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1471017-1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huxley, C., E. D. Green, and I. Dunham. 1990. Rapid assessment of S. cerevisiae mating type by PCR. Trends Genet. 6236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ip, S. C., U. Rass, M. G. Blanco, H. R. Flynn, J. M. Skehel, and S. C. West. 2008. Identification of Holliday junction resolvases from humans and yeast. Nature 456357-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ira, G., A. Pellicioli, A. Balijja, X. Wang, S. Fiorani, W. Carotenuto, G. Liberi, D. Bressan, L. Wan, N. M. Hollingsworth, J. E. Haber, and M. Foiani. 2004. DNA end resection, homologous recombination and DNA damage checkpoint activation require CDK1. Nature 4311011-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito, H., Y. Fukuda, K. Murata, and A. Kimura. 1983. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J. Bacteriol. 153163-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jinks-Robertson, S., and T. D. Petes. 1986. Chromosomal translocations generated by high-frequency meiotic recombination between repeated yeast genes. Genetics 114731-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadyk, L. C., and L. H. Hartwell. 1992. Sister chromatids are preferred over homologs as substrates for recombinational repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 132387-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawamoto, T., K. Araki, E. Sonoda, Y. M. Yamashita, K. Harada, K. Kikuchi, C. Masutani, F. Hanaoka, K. Nozaki, N. Hashimoto, and S. Takeda. 2005. Dual roles for DNA polymerase eta in homologous DNA recombination and translesion DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell 20793-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kesti, T., K. Flick, S. Keranen, J. E. Syvaoja, and C. Wittenberg. 1999. DNA polymerase epsilon catalytic domains are dispensable for DNA replication, DNA repair, and cell viability. Mol. Cell 3679-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krogh, B. O., and L. S. Symington. 2004. Recombination proteins in yeast. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38233-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langston, L. D., and L. S. Symington. 2004. Gene targeting in yeast is initiated by two independent strand invasions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10115392-15397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langston, L. D., and L. S. Symington. 2005. Opposing roles for DNA structure-specific proteins Rad1, Msh2, Msh3, and Sgs1 in yeast gene targeting. EMBO J. 242214-2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemoine, F. J., N. P. Degtyareva, K. Lobachev, and T. D. Petes. 2005. Chromosomal translocations in yeast induced by low levels of DNA polymerase a model for chromosome fragile sites. Cell 120587-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundblad, V., and E. H. Blackburn. 1993. An alternative pathway for yeast telomere maintenance rescues est1− senescence. Cell 73347-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lydeard, J. R., S. Jain, M. Yamaguchi, and J. E. Haber. 2007. Break-induced replication and telomerase-independent telomere maintenance require Pol32. Nature 448820-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malkova, A., M. L. Naylor, M. Yamaguchi, G. Ira, and J. E. Haber. 2005. RAD51-dependent break-induced replication differs in kinetics and checkpoint responses from RAD51-mediated gene conversion. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25933-944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maloisel, L., J. Bhargava, and G. S. Roeder. 2004. A role for DNA polymerase delta in gene conversion and crossing over during meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1671133-1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maloisel, L., F. Fabre, and S. Gangloff. 2008. DNA polymerase delta is preferentially recruited during homologous recombination to promote heteroduplex DNA extension. Mol. Cell. Biol. 281373-1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDonald, J. P., A. S. Levine, and R. Woodgate. 1997. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD30 gene, a homologue of Escherichia coli dinB and umuC, is DNA damage inducible and functions in a novel error-free postreplication repair mechanism. Genetics 1471557-1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McEachern, M. J., and J. E. Haber. 2006. Break-induced replication and recombinational telomere elongation in yeast. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75111-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McIlwraith, M. J., A. Vaisman, Y. Liu, E. Fanning, R. Woodgate, and S. C. West. 2005. Human DNA polymerase eta promotes DNA synthesis from strand invasion intermediates of homologous recombination. Mol. Cell 20783-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMurray, M. A., and D. E. Gottschling. 2003. An age-induced switch to a hyper-recombinational state. Science 3011908-1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merker, J. D., M. Dominska, and T. D. Petes. 2003. Patterns of heteroduplex formation associated with the initiation of meiotic recombination in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 16547-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mimitou, E. P., and L. S. Symington. 2008. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature 455770-774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morrison, A., R. B. Christensen, J. Alley, A. K. Beck, E. G. Bernstine, J. F. Lemontt, and C. W. Lawrence. 1989. REV3, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene whose function is required for induced mutagenesis, is predicted to encode a nonessential DNA polymerase. J. Bacteriol. 1715659-5667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morrow, D. M., C. Connelly, and P. Hieter. 1997. “Break copy” duplication: a model for chromosome fragment formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 147371-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nassif, N., J. Penney, S. Pal, W. R. Engels, and G. B. Gloor. 1994. Efficient copying of nonhomologous sequences from ectopic sites via P-element-induced gap repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 141613-1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nelson, J. R., C. W. Lawrence, and D. C. Hinkle. 1996. Thymine-thymine dimer bypass by yeast DNA polymerase zeta. Science 2721646-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nick McElhinny, S. A., D. A. Gordenin, C. M. Stith, P. M. Burgers, and T. A. Kunkel. 2008. Division of labor at the eukaryotic replication fork. Mol. Cell 30137-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osman, F., and M. C. Whitby. 2007. Exploring the roles of Mus81-Eme1/Mms4 at perturbed replication forks. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 61004-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paques, F., and J. E. Haber. 1999. Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63349-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pursell, Z. F., I. Isoz, E. B. Lundstrom, E. Johansson, and T. A. Kunkel. 2007. Yeast DNA polymerase epsilon participates in leading-strand DNA replication. Science 317127-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roseaulin, L., Y. Yamada, Y. Tsutsui, P. Russell, H. Iwasaki, and B. Arcangioli. 2008. Mus81 is essential for sister chromatid recombination at broken replication forks. EMBO J. 271378-1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanchez Garcia, J., L. F. Ciufo, X. Yang, S. E. Kearsey, and S. A. MacNeill. 2004. The C-terminal zinc finger of the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase delta is responsible for direct interaction with the B-subunit. Nucleic Acids Res. 323005-3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidt, K. H., J. Wu, and R. D. Kolodner. 2006. Control of translocations between highly diverged genes by Sgs1, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homolog of the Bloom's syndrome protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 265406-5420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sherman, F., G. Fink, and J. Hicks. 1986. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 52.Smith, C. E., B. Llorente, and L. S. Symington. 2007. Template switching during break-induced replication. Nature 447102-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stark, J. M., and M. Jasin. 2003. Extensive loss of heterozygosity is suppressed during homologous repair of chromosomal breaks. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23733-743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Symington, L. S. 2002. Role of RAD52 epistasis group genes in homologous recombination and double-strand break repair. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66630-670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.VanHulle, K., F. J. Lemoine, V. Narayanan, B. Downing, K. Hull, C. McCullough, M. Bellinger, K. Lobachev, T. D. Petes, and A. Malkova. 2007. Inverted DNA repeats channel repair of distant double-strand breaks into chromatid fusions and chromosomal rearrangements. Mol. Cell. Biol. 272601-2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang, X., G. Ira, J. A. Tercero, A. M. Holmes, J. F. Diffley, and J. E. Haber. 2004. Role of DNA replication proteins in double-strand break-induced recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 246891-6899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weinstock, D. M., C. A. Richardson, B. Elliott, and M. Jasin. 2006. Modeling oncogenic translocations: distinct roles for double-strand break repair pathways in translocation formation in mammalian cells. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 51065-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.White, M. A., and T. D. Petes. 1994. Analysis of meiotic recombination events near a recombination hotspot in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 2621-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu, Z., W. H. Chung, E. Y. Shim, S. E. Lee, and G. Ira. 2008. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell 134981-994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]