Abstract

The herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) gene UL12 encodes a conserved alkaline DNase with orthologues in all herpesviruses. The HSV-1 UL12 gene gives rise to two separately promoted 3′ coterminal mRNAs which encode distinct but related proteins: full-length UL12 and UL12.5, an amino-terminally truncated form that initiates at UL12 codon 127. Full-length UL12 localizes to the nucleus where it promotes the generation of mature viral genomes from larger precursors. In contrast, UL12.5 is predominantly mitochondrial and acts to trigger degradation of the mitochondrial genome early during infection. We examined the basis for these very different subcellular localization patterns. We confirmed an earlier report that the amino-terminal region of full-length UL12 is required for nuclear localization and provide evidence that multiple nuclear localization determinants are present in this region. In addition, we demonstrate that mitochondrial localization of UL12.5 relies largely on sequences located between UL12 residues 185 and 245 (UL12.5 residues 59 to 119). This region contains a sequence that resembles a typical mitochondrial matrix localization signal, and mutations that reduce the positive charge of this element severely impaired mitochondrial localization. Consistent with matrix localization, UL12.5 displayed a detergent extraction profile indistinguishable from that of the matrix protein cyclophilin D. Mitochondrial DNA depletion required the exonuclease activity of UL12.5, consistent with the idea that UL12.5 located within the matrix acts directly to destroy the mitochondrial genome. These results clarify how two highly related viral proteins are targeted to different subcellular locations with distinct functional consequences.

All members of the Herpesviridae encode a conserved alkaline DNase that displays limited homology to bacteriophage λ red α (2, 24), an exonuclease that acts in conjunction with the synaptase red β to catalyze homologous recombination between DNA molecules (23). The most thoroughly characterized member of the herpesvirus alkaline nuclease family is encoded by the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) gene UL12 (7, 9, 22). HSV-1 UL12 has both endo- and exonuclease activity (15-17, 36) and binds the viral single-stranded DNA binding protein ICP8 (37, 39) to form a recombinase that displays in vitro strand exchange activity similar to that for red α/β (27). UL12 localizes to the nucleus (26) where it plays an important, but as-of-yet ill-defined, role in promoting the production of mature packaged unit-length linear progeny viral DNA molecules (12, 20), perhaps via a recombination mechanism (27, 28). The importance of UL12 is documented by the observation that UL12 null mutants display a ca. 1,000-fold reduction in the production of infectious progeny virions (41).

HSV-1 also produces an amino-terminally truncated UL12-related protein termed UL12.5, which is specified by a separately promoted mRNA that initiates within UL12 coding sequences (7, 9, 21). UL12.5 is translated in the same reading frame as UL12 but initiates at UL12 codon 127 and therefore lacks the first 126 amino acid residues of the full-length protein. UL12.5 retains the nuclease and ICP8 binding activities of UL12 (4, 14, 26) but does not accumulate to high levels in the nucleus (26) and is unable to efficiently substitute for UL12 in promoting viral genome maturation (14, 21). We recently showed that UL12.5 localizes predominantly to mitochondria, where it triggers massive degradation of the host mitochondrial genome early during HSV infection (31). Mammalian mitochondrial DNA (mt DNA) is a 16.5-kb double-stranded circle located within the mitochondrial matrix that encodes 13 proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation and the RNA components of the mitochondrial translational apparatus (reviewed in reference 10). Inherited mutations that inactivate or deplete mt DNA impair oxidative phosphorylation, leading to a wide range of pathological conditions, including neuropathy and myopathy (reviewed in references 8 and 40). Thus, although the contribution of mt DNA depletion to the biology of HSV infection has yet to be determined, it likely has a major negative impact on host cell functions.

UL12 and UL12.5 provide a striking example of a pair of highly related proteins that share a common biochemical activity yet differ markedly in subcellular location and biological function. The basis for their distinct subcellular localization patterns is of considerable interest, as the only difference in the primary sequences is that UL12.5 lacks the first 126 residues of UL12. Reuven et al. (26) demonstrated that this UL12-specific region contains one or more signals able to target enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) to the nucleus. However, the determinants of the mitochondrial localization of UL12.5 have not been previously examined. Most proteins that are imported into the mitochondrial matrix bear a matrix targeting sequence that is located at or close to the amino terminus (reviewed in references 25 and 38). We speculated that UL12.5 bears such an amino-terminal matrix targeting sequence and that the function of this element is masked in the full-length UL12 protein by the UL12-specific amino-terminal extension, which contains the nuclear localization signal(s) (NLS). Our results broadly support this hypothesis and indicate that the mitochondrial localization sequence of UL12.5 is located ca. 60 residues from its N terminus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and plasmids.

Vero and HeLa cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 100 U of penicillin and streptomycin per ml supplemented with 5% or 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum for Vero and HeLa cells, respectively. The Vero-derived cell line 6-5, used to complement UL12 mutant viruses (35), was propagated in the medium described above supplemented with 400 U of Geneticin (G418; Amersham) per ml. The HSV-1 wild-type strain used in this study was KOS. The KOS-derived mutants AN1 (41), ANF1 (21), and M127F (19) were generously donated by Sandra Weller. Virus absorption, infections, and mock infections were carried out at 37°C. The wild-type virus was propagated, and the titer was determined in Vero cells. Mutants lacking functional UL12 and/or UL12.5 (AN1, ANF1, and M127F) were propagated on 6-5 cells. All infections were performed at a multiplicity of 10 PFU/cell. Plasmids pSAK12, pSAK12.5, and pSAK12.5-eGFP express HSV-1 UL12, UL12.5, and a UL12.5-eGFP fusion protein, respectively (26). pcDNA3.1-mOrange (31) expresses a modified version of monomeric red fluorescent protein, mOrange (34), with excitation and emission wavelengths of 548 and 562 nm, respectively.

Construction of mutant plasmids.

All of the primers used in the construction of mutant plasmids were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies. The indicated residue positions are relative to those of the full-length UL12 protein, and all plasmids created were verified by sequencing.

UL12 derivatives bearing progressive N-terminal deletions of the UL12-specific region (residues 1 to 126) were created by PCR amplification of the pSAK-UL12 vector using a reverse primer complementary to the 3′ end of the gene that also added a KpnI restriction site to facilitate subsequent cloning, 12rev (5′ GGGGTACCTCAGCGAGACGACCTCCCCG). This primer was used in conjunction with the following forward primers: Δ25 (5′-GGAATTCCGCCACCATGACCCCTCGTGGCCCCGAC), Δ50 (5′-GGAATTCCGCCACCATGCTGCCCCCCCCACCCCAG), Δ100 (5′-GGAATTCCGCCACCATGCCAGACATTCCGCTATCTCC), and Δ125 (5′-GGAATTCCGCCACCATGTCTATGTGGTCGGCGTCGG). PCR products were digested with EcoRI and KpnI and then ligated into pcDNA3.1 that had been cleaved with the same enzymes.

Additional UL12 derivatives encoding N-terminally truncated proteins that initiate at successive internal methionine residues downstream of M127 were made using PCR amplification of pSAK-UL12 with the primer 12rev and the following forward primers: M185 (5′-GGAATTCCGCCACCATGGTGGACCGCGGACTCGG), M215 (5′-GGAATTCCGCCACCATGGGGTTTTACGAGGCGGCC), M274 (5′-GGAATTCCGCCACCATGTTCGGGCGGGTGAACGAG), M328 (5′-GGAATTCCGCCACCATGGACGGTCACACGGGGATG), and M390 (5′-GGAATTCCGCCACCATGGCACACCGGTCCCCGG). PCR products were digested with EcoRI and KpnI and then ligated into pcDNA3.1 that had been cleaved with the same enzymes.

Plasmids containing UL12.5 sequences M185 to L214, M215 to R245, and M185 to R245 fused to the N terminus of eGFP in the pEGFP-C1 vector (Clontech) were constructed as follows. The eGFP sequence was cleaved out of pEGFP-C1 and inserted into the pUC19 vector (Invitrogen) using AgeI and BglII sites to create pUC19eGFP. The pEGFP-C1 vector lacking the eGFP sequence was then religated to create pEMPTY. Oligonucleotides OP1 (M185 to L214, 5′-CATGGTGGACCGCGGACTCGGTCGGCACCTATGGCGCCTGACGCGCCGCGGGCCCCCGGCCGCCGCGGACGCCGTGGCGCCCCGGCCCCT-3′) and OP2 (M215 to R245, 5′-CATGGGGTTTTACGAGGCGGCCACGCAAAACCAGGCCGACTGCCAGCTATGGGCCCTGCTCCGGCGGGGCCTCACGACCGCATCCACCCTCCG-3′) were inserted in frame with eGFP in the pUC19eGFP vector using the NcoI site present at the eGFP start codon. The M185-to-R245 plasmid was made by inserting OP1 into the OP2-containing pUC19eGFP plasmid, again using NcoI. The OP1-, OP2-, and OP1 plus OP2-eGFP fragments were finally transferred from their respective vectors back into pEMPTY using HindIII and KpnI sites to create pOP1EGFP, pOP2EGFP, and pOP1OP2EGFP, respectively.

The pSAK12.5-R → A-eGFP mutant plasmid was created using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) using primers harboring the alanine substitutions R188A, R192A, R196A, R199A, and R200A (forward, 5′-CATGGTGGACGCCGGACTCGGTGCGCACCTATGGGCCCTGACGGCCGCCGGGCCCCCGG; reverse, 5′CCGGGGGCCCGGCGGCCGTCAGGGCCCATAGGTGCGCACCGAGTCCGGCGTCCACCATG) and the pSAK12.5-eGFP plasmid as the template according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer.

A plasmid encoding a UL12.5-mOrange fusion protein was constructed as follows. pSAK-UL12.5-GFP was digested with KpnI and BamHI. The mOrange open reading frame was amplified from pRSET-Orange (34) using primers with restriction endonuclease cleavage sites appended to their 5′ ends so that the resulting amplimer could also be digested with KpnI and BamHI. The primer sequences were as follows: OrFor, 5′-CGGGGTACCGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAGAAT, and OrRev, 5′-CGCGGATCCTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGC. PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis was used to create the D340E and G336A/S338A mutant versions of UL12.5-mOrange using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and the following primers: D340E fwd (5′-GTCGGGGCGTCCCTGGAAATTCTCGTCTGTCC), D340E rev (5′-GGACAGACGAGAATTTCCAGGGACGCCCCGAC), dbl fwd (5′-CACACGGGGATGGTCGCGGCGGCCCTGGATATTCTCG), and dbl rev (5′-CGAGAATATCCAGGGCCGCCGCGACCATCCCCGTGTG).

Nucleic acid isolation and hybridization.

Total cellular RNA and DNA were harvested from 60-mm dishes and analyzed for mt RNA and DNA by Northern and Southern blot hybridization as previously described (31).

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

HeLa cells were seeded on coverslips in 12-well dishes prior to transfection. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the guidelines specified by the manufacturer. At 36 to 40 h posttransfection, cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed by incubation in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were then washed once in PBS and permeabilized in 0.5% NP-40 for 10 min at room temperature and processed for immunofluorescence as previously described (31), using a 1:4,000 dilution of rabbit polyclonal anti-UL12 antiserum (BWp12) (4, 20) or a 1:200 dilution of mouse monoclonal anti-cytochrome c (BD Biosciences). Cells were visualized and photographed under a Zeiss LSM 510 scanning argon (488 nm) and neon (543 nm) laser confocal microscope, using a 40× oil immersion objective.

Live cell imaging.

HeLa cells growing in four-chambered glass cover slides (Nunc) were cotransfected with the indicated plasmids and then evaluated for mt DNA depletion and/or subcellular localization of UL12.5 by live cell imaging as previously described (31). Cells were stained with PicoGreen (3 μl/ml; Invitrogen) for 1 h at 37°C to visualize mt DNA (3). After 30 min, MitoTracker Deep Red (1 mM; Invitrogen) was added and the cells were incubated for a further 30 min. In some experiments, MitoTracker Red CMXRos (50 nM; Invitrogen) was used instead. Cells were visualized and photographed with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope using a 40× oil immersion objective or a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M fluorescent microscope using a 63× oil immersion objective and an ApoTome optical sectioning device (Zeiss).

Image processing.

All images taken using the confocal microscope were acquired using the LSM 510 software (Zeiss). Images of live cells obtained using the Axiovert 200 M fluorescent microscope were acquired using the AxioVision 4.5 program (Zeiss). All image processing was performed using Photoshop CS2 (Adobe).

Western blotting.

Cell extracts were prepared and analyzed as previously described (6). Membranes were probed with rabbit anti-UL12 (1:10,000), anti-manganese-superoxide dismutase (MnSOD; 1:5,000; Stressgen), anti-β-actin (1:5,000; Sigma), or the antibodies present in the mitochondrial membrane integrity kit (1:1,000; MitoSciences). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse immunoglobulin secondary antibodies were purchased from Sigma and used at a 1:5,000 dilution. Secondary antibody was detected using ECL Plus (Amersham Biosciences) detection reagents according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Isolation of mitochondria and digitonin treatment of the mitochondrial fraction.

Two 150-mm dishes of HeLa cells were transfected with either pcDNA3-UL12.5 or empty vector using Lipofectamine 2000. Thirty-six to 48 h after transfection, cells were harvested using trypsin-EDTA and pooled, and the cell pellet was obtained by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min at room temperature. The cell pellet was washed twice with PBS and resuspended in 0.5 ml of ice-cold mitochondrial isolation buffer (200 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 1 mM EGTA). Cells were mechanically disrupted using 35 up-and-down strokes of a Teflon Dounce homogenizer set at 700 rpm, and nuclei and unbroken cells were removed from the homogenate by centrifugation at 560 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and the mitochondrion-containing heavy membrane fraction was isolated by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of mitochondrial isolation buffer and termed the mitochondrial fraction. The supernatant, also containing small membrane vesicles, was termed the cytosolic fraction. The amount of total protein in each fraction was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. A total of 20 to 25 μg protein from each fraction was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotting as described above.

To assess the submitochondrial localization of UL12.5, the mitochondrial pellet was isolated by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed twice in mitochondrial isolation buffer and resuspended in 100 μl of mitochondrial isolation buffer. The total protein content of the mitochondrial preparation was determined as described above. Equal aliquots of 12 to 20 μg of protein were treated with 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, or 8 μg of digitonin per microgram of total protein for 45 to 60 min on ice, with occasional mixing. The partially disrupted mitochondria/mitoplasts were isolated by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 1× protein sample buffer and analyzed for protein content by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as described above.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Full-length UL12.5 is not essential for mt DNA depletion during HSV-1 infection.

As reviewed in the introduction, the HSV-1 UL12 gene gives rise to two separately promoted 3′ coterminal mRNAs which encode distinct but related proteins: full-length UL12 and UL12.5, an amino-terminally truncated form that initiates at UL12 codon 127. We previously demonstrated that transiently expressed UL12.5 localizes to mitochondria and depletes mt DNA in the absence of other HSV gene products (31); in contrast, UL12, a nuclear protein (26), displays greatly reduced mitochondrial depleting activity (31). To assess the roles of UL12 and UL12.5 in mt DNA depletion during HSV-1 infection, we examined the effects of mutations that selectively eliminate production of either protein. ANF1 contains a 2-bp insertion at the 5′ end of the UL12 gene and therefore fails to produce UL12; however, translation of UL12.5 is unaffected (21). In contrast, the M127F mutation alters the start codon of UL12.5, preventing production of full-length UL12.5 without impairing the function of UL12 (19).

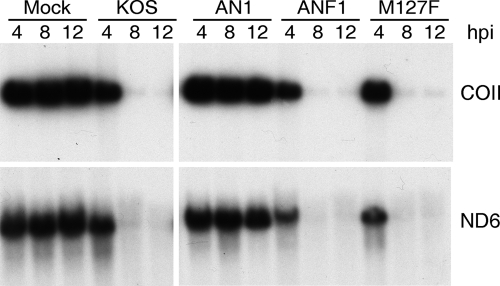

Viruses bearing the ANF1 and M127F mutations were used to infect Vero cells, and the fate of host mt DNA was assayed by Southern blot hybridization (Fig. 1). As previously shown (31), wild-type HSV-1 strongly depleted mt DNA at early times postinfection while the UL12/UL12.5 null virus AN1 (41) had no effect (Fig. 1). ANF1, which produces only UL12.5, retained the ability to deplete the mitochondrial genome, as expected on the basis of our previous work (31). Interestingly, the M127F virus, which produces UL12 but cannot generate intact UL12.5, also retained the ability to eliminate mt DNA (Fig. 1). Nuclear DNA was not depleted by any of the viruses (data not shown). The M127F mutation is predicted to shift the site of translational initiation on UL12.5 mRNA to the next downstream AUG codon, which encodes UL12 residue M185. We speculated that the resulting amino-terminally truncated version of UL12.5 is competent to deplete mt DNA.

FIG. 1.

The HSV-1 M127F virus depletes mt DNA. Vero cells were infected with 10 PFU/cell of the indicated virus, and total cellular DNA was extracted 4, 8, and 12 h postinfection. DNA was cleaved with HpaI and then analyzed by Southern blot hybridization using probes for cytochrome c oxidase subunit II (COII) and NAD dehydrogenase subunit 6 (ND6). Mock, mock infection; hpi, hours postinfection.

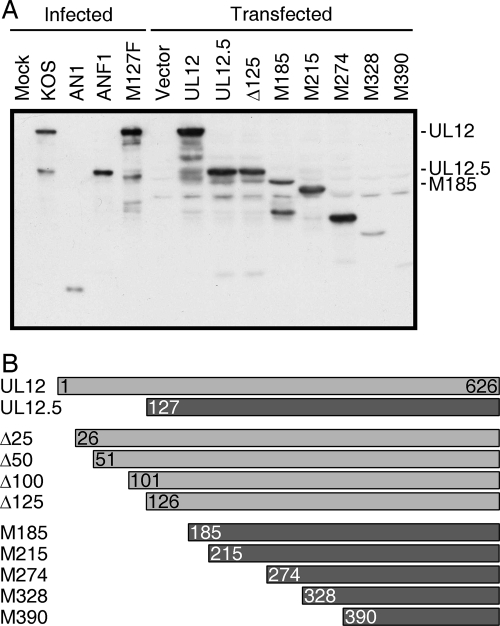

These results prompted us to examine the UL12-related proteins expressed during infection with the various UL12 mutant viruses. To this end, total cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-UL12 polyclonal antibody (Fig. 2A). As expected, cells infected with wild-type KOS produced both UL12 (ca. 85 kDa) and UL12.5 (ca. 55 kDa), while AN1 failed to produce either protein (Fig. 2A). ANF1 produced only UL12.5, as previously reported (21) (Fig. 2A). However, also as previously reported (19), the M127F mutant produced several UL12-reactive species in addition to UL12, including some that migrated more rapidly than UL12.5. The largest of these more rapidly migrating bands had a mobility that was indistinguishable from that expected for the protein initiating at M185. These data therefore supported the idea that the N-terminally truncated form of UL12.5 initiated at M185 is responsible for mt DNA depletion by the M127F mutant.

FIG. 2.

UL12-related proteins produced in infected and transfected cells. (A) HeLa cells were either infected with the indicated HSV-1 strain (10 PFU/cell) or transfected with the indicated UL12 expression construct. Cells were then lysed in protein sample buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting using a polyclonal antiserum generated against UL12. Products generated by the Δ25, Δ50, and Δ100 mutants are shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. The electrophoretic mobilities of UL12, UL12.5, and ULM185 are indicated to the right. Mock, mock infection. (B) The structures of the N-terminally truncated UL12 derivatives are indicated.

A truncated version of UL12 initiating at methionine 185 is capable of depleting mt DNA.

To test the hypothesis that a truncated version of UL12 initiating at M185 is capable of depleting mt DNA and to further examine the determinants for mitochondrial localization and mt DNA depletion, we constructed a series of plasmids that express UL12 derivatives bearing progressive in-frame deletions from the N terminus (Fig. 2B). Truncations to positions upstream of M127 were generated by removing 25, 50, 100, or 125 amino acids from the N terminus of the protein and placing an AUG start codon at the beginning of the truncated sequence; these constructs were named according to the size of the deletion (the Δ25, Δ50, Δ100, and Δ125 mutants). Truncations extending downstream of M127 took advantage of the successive in-frame AUG codons located within the UL12.5 coding sequence; these were designated according to the position of the new start codon (UL12M185, UL12M215, UL12M274, UL12M328, and UL12M390). In order to confirm expression, HeLa cells were transfected with the various constructs and analyzed by immunoblotting with the anti-UL12 antiserum (Fig. 2A and see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). All of the constructs gave rise to one or more major immunoreactive species, and in each case the largest of these migrated with approximately the predicted mobility. In addition to the major predicted species, the expression vectors encoding UL12, UL12.5, the Δ25, Δ50, Δ100, and Δ125 mutants, and UL12M185 gave rise to a number of more rapidly migrating species, some very similar in mobility to those produced by the M127F virus. The pattern obtained with these expression plasmids contrasts with the clear two-band expression profile of the wild-type virus, and the nature and origin of the additional bands remain unknown. The largest species produced by the UL12M185 construct migrated at a position similar to that of the major truncated form expressed by the M127F virus (Fig. 2A), consistent with the expectation that M127F produces the UL12M185 protein.

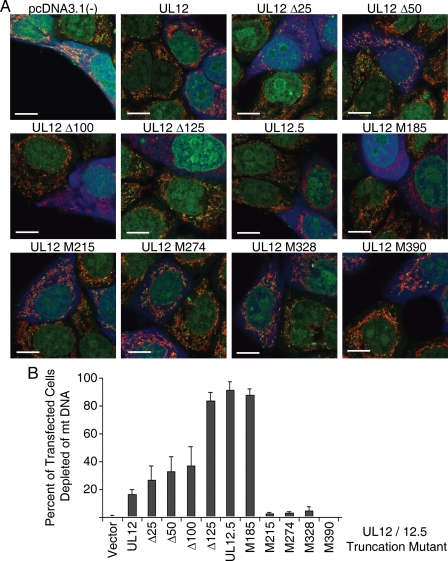

We next examined the ability of the various truncated UL12 proteins to deplete mt DNA when expressed in the absence of other viral proteins. HeLa cells were cotransfected with the UL12 expression plasmids and a vector encoding an orange variant of red fluorescent protein, mOrange (31, 34), which was included to mark transfected cells. After 48 h, live cells were stained with PicoGreen, a DNA dye previously shown to label mt DNA nucleoids (3), and MitoTracker Deep Red, which marks the mitochondrial network. The cells were also scored for expression of mOrange to identify the successfully transfected subset (false-colored blue). As expected, cells transfected with the empty UL12 expression vector displayed numerous cytoplasmic green punctae located within the mitochondrial fibrillar network (Fig. 3A), indicating the presence of mt DNA. In contrast, as previously described (31), most of the cells transfected with the UL12.5 expression plasmid lacked PicoGreen-stained mitochondrial foci (Fig. 3A). For each of the cotransfections performed, the extent of mt DNA depletion was quantified by counting the number of transfected cells that lacked green mt DNA foci (Fig. 3B). Using this quantitative method, we determined that over 90% of UL12.5-transfected cells were devoid of mt DNA, while this value was less than 20% for UL12-transfected cells (Fig. 3B). As the UL12-specific amino-terminal region was progressively removed in the Δ25, Δ50, Δ100, and Δ125 mutants, the efficiency of mt DNA depletion increased to approach that of UL12.5 (ca. 30%, 35%, 40%, and 85%, respectively) (Fig. 3B). These data indicate that the UL12-specific region, which targets UL12 to the nucleus (26), inhibits mt DNA depletion. Of particular note, the UL12M185 construct depleted mt DNA as efficiently as UL12.5, while further truncation (to M215, M274, M328, and M390) eliminated mt DNA depletion (Fig. 3B and representative panels in 3A). These results demonstrate that an amino-terminally truncated form of UL12.5 initiating at codon 185 retains all of the features required to target and destroy mt DNA. Presumably, this protein accounts at least in part for the ability of the M127F virus to deplete mt DNA.

FIG. 3.

mt DNA depletion by N-terminally truncated forms of UL12. (A) Expression plasmids encoding N-terminally truncated forms of UL12 were transfected into HeLa cells along with a plasmid expressing mOrange. Forty-eight hours after transfection, live cells were stained with PicoGreen to visualize mt DNA and MitoTracker Deep Red to visualize the mitochondrial network. The mOrange signal was false-colored blue and used to identify transfected cells. Bars = 10 μm. (B) Efficiency of mt DNA depletion by the various constructs. The percentage of transfected cells lacking mt DNA (no green staining) was determined for each construct by counting a minimum of 10 random fields of view and a minimum of 50 transfected cells in each experiment. The average from three separate experiments ± the standard error is plotted.

UL12M185 localizes to mitochondria.

The simplest hypothesis to explain mt DNA depletion by UL12.5 and other UL12 derivatives is that these proteins target the mitochondrial matrix and directly degrade mt DNA. If so, then mt DNA depletion should require mitochondrial localization. We therefore examined the subcellular localization of the various truncated UL12 derivatives to test this prediction and map the sequences that target UL12.5 to mitochondria (Fig. 4). Transfected HeLa cells were fixed and immunostained with the anti-UL12 antiserum (red) and a monoclonal antibody against the mitochondrial protein cytochrome c (green). As reported previously (26, 31), UL12 localized to the nucleus while UL12.5 displayed reduced nuclear staining and targeted mitochondria (Fig. 4A). Constructs lacking 25 and 50 amino-terminal residues retained the predominantly nuclear localization of UL12, while the Δ100 mutant displayed both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining. The Δ125 mutant resembled UL12.5 in that it gave rise to a clear mitochondrial signal and reduced nuclear staining, while UL12M185 appeared to be exclusively mitochondrial. Further truncation of the protein to UL12M215 and beyond abolished mitochondrial targeting, with the notable exception of UL12M390, which appeared to be exclusively mitochondrial (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, UL12.5M274 displayed a predominantly nuclear localization pattern, perhaps suggesting that a cryptic NLS is unmasked by this truncation.

FIG. 4.

Subcellular localization of N-terminally truncated UL12 derivatives. (A) HeLa cells transfected with the indicated expression plasmids were fixed 48 h after transfection and then immunostained for UL12 (red) and cytochrome c (green). A yellow color indicates colocalization of the UL12 derivative with the mitochondrial network. Bars = 10 μm. (B) The first 60 amino acids of UL12.5, UL12M185, and UL12M390 are depicted. Positively charged residues are indicated. The probability of the mitochondrial import of each protein predicted by the computer algorithm MitoProt is indicated.

We drew three major conclusions from these data. First, as previously suggested, sequences in the UL12-specific region (residues 1 to 126) play a major role in the nuclear localization of this protein. Reuven et al. (26) demonstrated that this sequence contains one or more NLS capable of directing eGFP to the nucleus and suggested that the sequence KRPRP (residues 35 to 39) fulfills this function. While this sequence has been shown to serve as an NLS in other proteins (18, 29), our results document that it is not the sole determinant for nuclear localization of UL12, as the Δ50 truncation mutant, which lacks this element, displayed normal nuclear localization (Fig. 4). In contrast, the deletion mutant lacking 100 amino acids was found in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, and both the Δ125 mutant and UL12.5 displayed nuclear and mitochondrial staining. These data suggest that sequences located between residues 50 and 100 are required for the exclusively nuclear localization displayed by UL12 and imply that one or more elements located downstream of M127 can also serve as a weaker NLS.

Second, the data suggested that the UL12 open reading frame contains at least two regions that are capable of directing mitochondrial localization when suitably presented close to the N terminus of the polypeptide. One of these elements displays activity in the Δ125 mutant, UL12.5, and especially UL12M185, and the other was exposed by truncation to UL12M390. Proteins that are destined for import into the mitochondrial matrix typically bear an amino-terminal matrix targeting sequence that adopts an amphipathic α-helical configuration (25, 38). Consistent with this expectation, the MitoProt computer algorithm (5) predicted that the UL12M185 and UL12M390 truncated proteins both have a very high probability of import into the mitochondrial matrix (Fig. 4B); in contrast, UL12.5 was assigned a low probability, indicating that its N-terminal sequence does not strongly resemble a matrix targeting sequence. This result raised the possibility that the mitochondrial import of UL12.5 might rely on the predicted matrix localization sequence immediately downstream of M185.

Third, with the exception of UL12M390, the mitochondrial localization phenotypes of the UL12 derivatives correlated with their abilities to deplete mt DNA (Fig. 3 and 4). However, it is important to emphasize that UL12 and the Δ25, Δ50, and Δ100 mutants all displayed measurable mt DNA-depleting activities without obviously localizing to mitochondria. We presume that these constructs give rise to low levels of mitochondrial UL12 that are not readily detected by microscopy, either through the generation of UL12.5-like products through proteolysis or weak activity of internal mitochondrial localization sequences. In contrast, UL12M390 efficiently targeted mitochondria but failed to deplete mt DNA. This truncated protein lacks the majority of the region of UL12 that is strongly conserved between the alkaline nuclease orthologues encoded by other herpesviruses (which extends from UL12 residues 214 to 576), as well as residues specifically shown to be required for nuclease activity of the protein (13). UL12M390 therefore almost certainly lacks nuclease activity. Overall, these results are broadly consistent with the hypothesis that UL12.5 acts in the mitochondrial matrix to trigger mt DNA depletion.

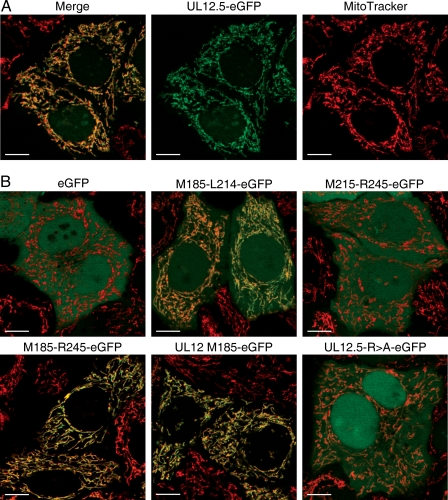

UL12.5 utilizes a mitochondrial localization signal located downstream of its amino terminus.

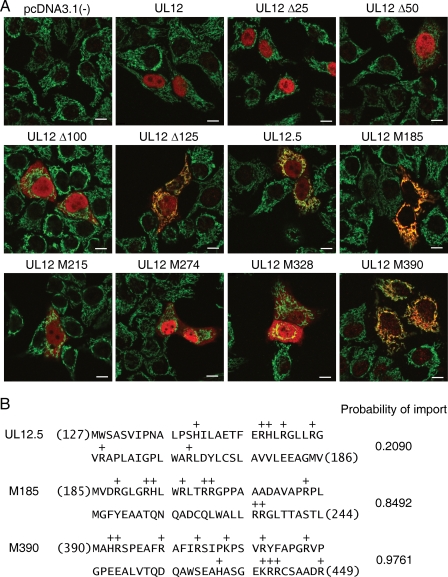

The preceding data raised the possibility that mitochondrial localization of UL12.5 relies on sequences located downstream of M185 (i.e., 60 or more residues from the N terminus of UL12.5). To test this hypothesis, we first examined the ability of this segment to redirect an unrelated protein to mitochondria by fusing residues M185 to L214, M185 to R245, and M215 to R245 to the amino terminus of eGFP. The subcellular localization of these fusion proteins was then evaluated by fluorescence microscopy of living cells stained with MitoTracker Red (Fig. 5). UL12 residues 185 to 214 partially redirected eGFP to mitochondria (UL12M185-L214-eGFP), while residues 185 to 245 displayed more robust activity (UL12M185-R245-eGFP), as indicated by the complete overlap of the eGFP signal with MitoTracker Red (Fig. 5B). In contrast, the M215 to R245 sequence did not redirect eGFP to mitochondria on its own (UL12M215-R245-eGFP). The localization pattern of UL12M185-R245-eGFP was indistinguishable from that displayed by two positive controls, the UL12.5-eGFP fusion (Fig. 5A) and truncated UL12.5 initiated at M185 fused to eGFP (UL12M185-eGFP) (Fig. 5B). These data demonstrate that the M185-to-R245 segment can serve as an autonomous mitochondrial localization sequence. As noted above, this interval is predicted to form an amphipathic α helix with a positively charged face (Fig. 4B). To test the role of these positively charged residues, we replaced the first five arginine residues downstream of M185 (R188, R192, R196, R199, and R200) with alanine residues. These R → A substitutions severely reduced the mitochondrial localization of the UL12.5M185-R245 fusion protein (data not shown). More importantly, these same substitutions also greatly reduced (but did not eliminate) mitochondrial localization of UL12.5-eGFP (UL12.5R → A-eGFP) (Fig. 5B and data not shown). In contrast, comparable R → A substitutions of the four arginine residues found between UL12 residues 148 and 158 (R148, R151, R155, and R158) had no effect on the mitochondrial localization of UL12.5-eGFP (data not shown). These data indicate that UL12.5 residues located approximately 60 amino acids downstream from its amino terminus play a major role in targeting UL12.5 to mitochondria. It is possible that the residual mitochondrial targeting of the UL12.5R → A mutant is due to the residual positively charged residues remaining in the mutant 185 to 245 region; alternatively, it might depend on the second predicted localization signal located downstream of M390.

FIG. 5.

Residues downstream of M185 are crucial for mitochondrial localization of UL12.5. (A) UL12.5-eGFP colocalizes with mitochondria in transfected cells. HeLa cells transfected with a UL12.5-eGFP expression plasmid were visualized by fluorescence microscopy after staining with MitoTracker Red. (B) HeLa cells transfected with plasmids encoding eGFP or the indicated UL12.5-eGFP fusion proteins were examined by live cell imaging as described for panel A. UL12.5-R → A-eGFP: UL12.5-eGFP bearing R → A substitutions at residues 188, 192, 196, 199, and 200. Bars = 10 μm.

The mitochondrial localization sequence of most proteins that are imported from the cytoplasm into the mitochondrial matrix is located in a presequence that is cleaved from the precursor protein during the import process by matrix proteases (reviewed in references 25 and 38). Our data indicate that UL12.5 and the UL12M185 truncation mutant utilize the same mitochondrial localization signal, which is located between UL12 residues 185 and 245 (Fig. 4 and 5). If this sequence were cleaved from both proteins following import, then UL12.5 and UL12M185 would give rise to identical imported products. However, the major UL12.5 species detected in infected and transfected cells clearly resolves from the largest product arising from the UL12M185 expression vector (Fig. 2). These data suggest that the mitochondrial targeting sequence of UL12.5, and possibly UL12M185, is not efficiently removed. Cleavage-resistant mitochondrial matrix targeting sequences have been described for a small number of cellular proteins (1, 11, 30). Further studies involving N-terminal sequencing of mitochondrial UL12.5 and UL12M185 are required to investigate this possibility.

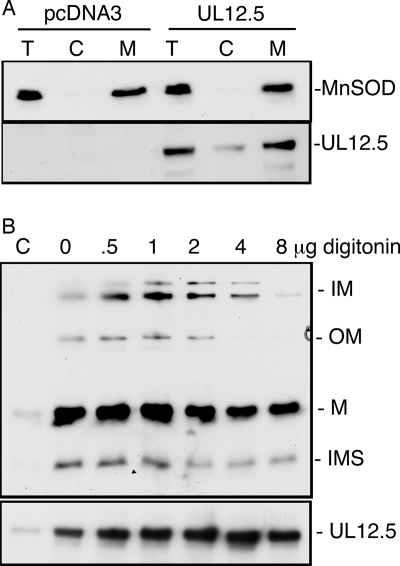

Evidence that UL12.5 targets the mitochondrial matrix.

UL12.5 localizes to mitochondria as judged by confocal microscopy, but this technique does not provide any information regarding the mitochondrial subcompartment to which UL12.5 is targeted. The mitochondrial genome is located within the mitochondrial matrix, and it therefore seemed plausible that UL12.5 is directed to this domain. We used subcellular fractionation and differential extraction with digitonin (1, 32) as one approach to test this hypothesis. HeLa cells transfected with the UL12.5 expression vector were fractionated into mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions as described in Materials and Methods, and the distribution of UL12.5 in each fraction was determined by immunoblotting. The majority of the UL12.5 present in the postnuclear supernatant partitioned with the mitochondrial fraction along with the mitochondrial marker MnSOD (Fig. 6A), confirming the mitochondrial localization of UL12.5. We then treated the isolated mitochondrial fraction with increasing concentrations of digitonin. After each detergent treatment, the remaining mitochondria/mitoplasts were isolated by centrifugation and analyzed by immunoblotting for the presence of UL12.5 and markers of the various mitochondrial subcompartments. The majority of UL12.5 remained in the pellet after treatment with the highest concentration of digitonin, as did the mitochondrial matrix marker protein cyclophilin D (Fig. 6B). Although not completely definitive, these data suggest that UL12.5 targets the mitochondrial matrix.

FIG. 6.

UL12.5 localizes to the mitochondrial matrix. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with empty vector or a UL12.5 expression plasmid. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were either lysed directly in protein sample buffer (T) or removed from the dish and disrupted by Dounce homogenization. Mechanically broken cells were separated into cytosol- or mitochondrion-containing fractions (C and M, respectively) by differential centrifugation. Total protein (20 μg) from each fraction was subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using antiserum against UL12 or the mitochondrial matrix protein, MnSOD. (B) Digitonin extraction profile of UL12.5. Aliquots of the mitochondrial pellet were treated with 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, or 8 μg of digitonin per microgram of total protein for 45 to 60 min on ice. The disrupted mitochondrion/mitoplast-containing pellets were isolated by centrifugation and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using anti-UL12 or anti-mitoplast mix, an antibody cocktail that recognizes a protein(s) from each subcompartment of the mitochondrion. The marker proteins for each subcompartment of the mitochondrion are inner membrane (IM), C-V-α and C-III-Core1; outer membrane (OM), porin 1 and 2; matrix (M), cyclophilin D; and intermembrane space (IMS), cytochrome c.

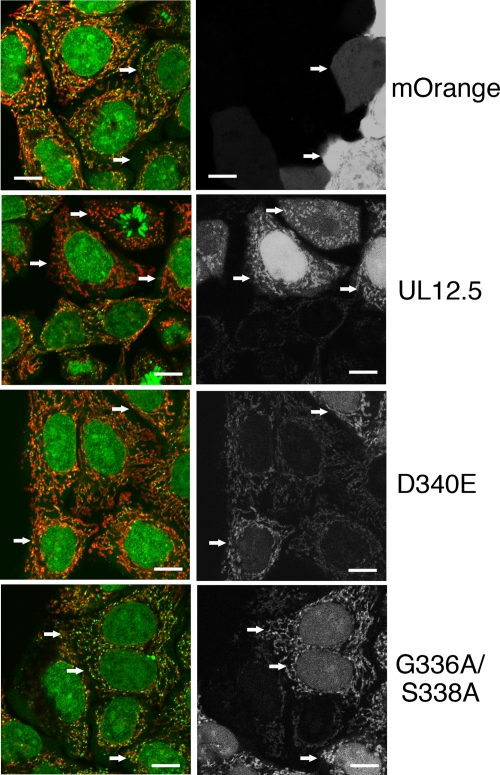

Evidence that depletion of mt DNA requires the exonuclease activity of UL12.5.

Goldstein and Weller (13) documented that UL12 displays seven sequence motifs that are highly conserved among the alkaline nucleases of diverse herpesviruses. These authors also demonstrated that residues within motif II are critical for catalytic activity; a mutation that changed residue D340 to E (D340E) eliminated exonuclease activity but left endonuclease activity intact, while the G336A/S338A double mutation eliminated both activities. As a first step in evaluating the contribution of the nuclease activities of UL12.5 to mt DNA depletion, we tested the effects of the D340E and G336A/S338A lesions. We first constructed a plasmid that expresses a UL12.5-mOrange fusion protein and then transferred the D340E and G336A/S338A mutations into this background. HeLa cells transfected with these constructs were then scored for mt DNA depletion by live cell imaging after staining with PicoGreen and MitoTracker Deep Red (Fig. 7). As expected, the UL12.5-mOrange fusion protein localized to mitochondria and depleted mt DNA. In contrast, UL12.5-mOrange bearing either the D340E or G336A/S338A lesion failed to deplete mt DNA, despite localizing normally to mitochondria. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that UL12.5 acts directly on mt DNA and suggest that its exonuclease activity is critical for mt DNA depletion. The mitochondrial genome is a covalently closed circle (33), and hence endonuclease activity is almost certainly also required to initiate the degradation process. Further studies are required to determine whether UL12.5 acts as the endonucleolytic trigger; an alternative possibility is that cellular nucleases collaborate in the degradation process.

FIG. 7.

Evidence that the nuclease activity of UL12.5 is required for mt DNA depletion. HeLa cells transfected with plasmids expressing the indicated mOrange-UL12.5 fusion proteins were stained with PicoGreen and MitoTracker Deep Red 48 h after transfection (left panels). The mOrange signal observed in the same field of view is displayed in the right panels. Selected transfected cells are indicated by arrows. UL12.5, UL12.5-mOrange fusion protein; D340E and G336A/S338A, UL12.5-mOrange fusion proteins bearing the indicated amino acid substitutions. Bar = 10 μm.

The preceding data are consistent with the idea that UL12.5 acts directly to degrade mt DNA through its nuclease activities. However, additional work is required to further test this hypothesis. Perhaps arguing against this simple model, Henderson et al. (14) have documented that a mutation that removes UL12 residues 2 to 148 inactivates the nuclease activity of in vitro-translated UL12. These results raise the possibility that the UL12M185 protein, which lacks these and additional residues, may similarly be devoid of enzymatic activity, despite its ability to efficiently deplete mt DNA in vivo. Further studies are therefore required to systematically explore the relationship between mt DNA depletion and the nuclease activities of UL12.5.

Concluding remarks.

Our results clarify the basis for the distinct subcellular localization patterns of UL12 and UL12.5 and support the hypothesis that UL12.5 acts directly within the mitochondrial matrix to trigger mt DNA loss. However, our experiments have yet to address two key outstanding questions. First, if mt DNA is directly degraded by UL12.5, why is nuclear DNA resistant to UL12 (31)? Perhaps UL12 is unable to access DNA that is organized into nucleosomal chromatin; alternatively, it is possible that the UL12-specific amino-terminal extension acts to restrain nuclease activity. Further studies are required to test these and other possibilities. Second, does mt DNA depletion benefit HSV-1, and if so, how is this benefit achieved? Depletion of mt DNA is conserved between HSV-1 and HSV-2 (31), whose UL12 loci display 19% DNA sequence divergence (9); hence, this activity is almost certainly under positive selection. Indeed, HSV-2 produces two UL12 mRNAs analogous to the HSV-1 UL12 and UL12.5 messages, and the smaller of these is predicted to give rise to a truncated protein that is highly similar to HSV-1 UL12.5 (9). Previous efforts to define the role of UL12.5 in the biology of HSV infection have employed the M127F mutation (26), which has little if any effect on virus replication in tissue culture. However, as we show here, the viral isolate bearing the M127F lesion retains the ability to deplete mt DNA, most likely because it produces an active UL12.5 derivative that initiates at M185. We currently seek to generate HSV-1 isolates bearing additional mutations that abrogate mt DNA depletion without affecting the important nuclear functions of UL12. These studies will be crucial in providing insight into the biological significance of mt DNA loss during HSV-1 infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rob Maranchuk for technical assistance, Sandra Weller for gifts of viruses, plasmids, and the UL12 antiserum, and Roger Tsien for gifts of plasmids.

This research was funded by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (FRN37995).

J.R.S. is a Canada Research Chair in Molecular Virology.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 January 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amaya, Y., H. Arakawa, M. Takiguchi, Y. Ebina, S. Yokota, and M. Mori. 1988. A noncleavable signal for mitochondrial import of 3-oxoacyl-CoA thiolase. J. Biol. Chem. 26314463-14470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aravind, L., K. S. Makarova, and E. V. Koonin. 2000. Survey and summary: holliday junction resolvases and related nucleases: identification of new families, phyletic distribution and evolutionary trajectories. Nucleic Acids Res. 283417-3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashley, N., D. Harris, and J. Poulton. 2005. Detection of mitochondrial DNA depletion in living human cells using PicoGreen staining. Exp. Cell Res. 303432-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bronstein, J. C., S. K. Weller, and P. C. Weber. 1997. The product of the UL12.5 gene of herpes simplex virus type 1 is a capsid-associated nuclease. J. Virol. 713039-3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claros, M. G., and P. Vincens. 1996. Computational method to predict mitochondrially imported proteins and their targeting sequences. Eur. J. Biochem. 241779-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corcoran, J. A., W. L. Hsu, and J. R. Smiley. 2006. Herpes simplex virus ICP27 is required for virus-induced stabilization of the ARE-containing IEX-1 mRNA encoded by the human IER3 gene. J. Virol. 809720-9729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa, R. H., K. G. Draper, L. Banks, K. L. Powell, G. Cohen, R. Eisenberg, and E. K. Wagner. 1983. High-resolution characterization of herpes simplex virus type 1 transcripts encoding alkaline exonuclease and a 50,000-dalton protein tentatively identified as a capsid protein. J. Virol. 48591-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimauro, S. 2004. Mitochondrial medicine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1659107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Draper, K. G., G. Devi-Rao, R. H. Costa, E. D. Blair, R. L. Thompson, and E. K. Wagner. 1986. Characterization of the genes encoding herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 alkaline exonucleases and overlapping proteins. J. Virol. 571023-1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernández-Silva, P., J. A. Enriquez, and J. Montoya. 2003. Replication and transcription of mammalian mitochondrial DNA. Exp. Physiol. 8841-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furuta, S., A. Kobayashi, S. Miyazawa, and T. Hashimoto. 1997. Cloning and expression of cDNA for a newly identified isozyme of bovine liver 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase and its import into mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1350317-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein, J. N., and S. K. Weller. 1998. In vitro processing of herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA replication intermediates by the viral alkaline nuclease, UL12. J. Virol. 728772-8781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein, J. N., and S. K. Weller. 1998. The exonuclease activity of HSV-1 UL12 is required for in vivo function. Virology 244442-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson, J. O., L. J. Ball-Goodrich, and D. S. Parris. 1998. Structure-function analysis of the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL12 gene: correlation of deoxyribonuclease activity in vitro with replication function. Virology 243247-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann, P. J. 1981. Mechanism of degradation of duplex DNA by the DNase induced by herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 381005-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann, P. J., and Y. C. Cheng. 1978. The deoxyribonuclease induced after infection of KB cells by herpes simplex virus type 1 or type 2. I. Purification and characterization of the enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2533557-3562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knopf, C. W., and K. Weisshart. 1990. Comparison of exonucleolytic activities of herpes simplex virus type-1 DNA polymerase and DNase. Eur. J. Biochem. 191263-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ling, P. D., J. J. Ryon, and S. D. Hayward. 1993. EBNA-2 of herpesvirus papio diverges significantly from the type A and type B EBNA-2 proteins of Epstein-Barr virus but retains an efficient transactivation domain with a conserved hydrophobic motif. J. Virol. 672990-3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez, R., J. N. Goldstein, and S. K. Weller. 2002. The product of the UL12.5 gene of herpes simplex virus type 1 is not essential for lytic viral growth and is not specifically associated with capsids. Virology 298248-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez, R., R. T. Sarisky, P. C. Weber, and S. K. Weller. 1996. Herpes simplex virus type 1 alkaline nuclease is required for efficient processing of viral DNA replication intermediates. J. Virol. 702075-2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez, R., L. Shao, J. C. Bronstein, P. C. Weber, and S. K. Weller. 1996. The product of a 1.9-kb mRNA which overlaps the HSV-1 alkaline nuclease gene (UL12) cannot relieve the growth defects of a null mutant. Virology 215152-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGeoch, D. J., A. Dolan, and M. C. Frame. 1986. DNA sequence of the region in the genome of herpes simplex virus type 1 containing the exonuclease gene and neighbouring genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 143435-3448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muyrers, J. P., Y. Zhang, F. Buchholz, and A. F. Stewart. 2000. RecE/RecT and Redalpha/Redbeta initiate double-stranded break repair by specifically interacting with their respective partners. Genes Dev. 141971-1982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myers, R. S., and K. E. Rudd. 1998. Mining DNA sequences for molecular enzymology: the Reda superfamily defines a set of DNA recombinase nucleases, p. 49-50. Proceedings of the 1998 Miami Nature Biotechnology Winter Symposium. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 25.Omura, T. 1998. Mitochondria-targeting sequence, a multi-role sorting sequence recognized at all steps of protein import into mitochondria. J. Biochem. 1231010-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reuven, N. B., S. Antoku, and S. K. Weller. 2004. The UL12.5 gene product of herpes simplex virus type 1 exhibits nuclease and strand exchange activities but does not localize to the nucleus. J. Virol. 784599-4608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reuven, N. B., A. E. Staire, R. S. Myers, and S. K. Weller. 2003. The herpes simplex virus type 1 alkaline nuclease and single-stranded DNA binding protein mediate strand exchange in vitro. J. Virol. 777425-7433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reuven, N. B., S. Willcox, J. D. Griffith, and S. K. Weller. 2004. Catalysis of strand exchange by the HSV-1 UL12 and ICP8 proteins: potent ICP8 recombinase activity is revealed upon resection of dsDNA substrate by nuclease. J. Mol. Biol. 34257-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richardson, W. D., B. L. Roberts, and A. E. Smith. 1986. Nuclear location signals in polyoma virus large-T. Cell 4477-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryan, M. T., N. J. Hoogenraad, and P. B. Hoj. 1994. Isolation of a cDNA clone specifying rat chaperonin 10, a stress-inducible mitochondrial matrix protein synthesised without a cleavable presequence. FEBS Lett. 337152-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saffran, H. A., J. M. Pare, J. A. Corcoran, S. K. Weller, and J. R. Smiley. 2007. Herpes simplex virus eliminates host mitochondrial DNA. EMBO Rep. 8188-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schnaitman, C., and J. W. Greenawalt. 1968. Enzymatic properties of the inner and outer membranes of rat liver mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 38158-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shadel, G. S., and D. A. Clayton. 1997. Mitochondrial DNA maintenance in vertebrates. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66409-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaner, N. C., R. E. Campbell, P. A. Steinbach, B. N. Giepmans, A. E. Palmer, and R. Y. Tsien. 2004. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 221567-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shao, L., L. M. Rapp, and S. K. Weller. 1993. Herpes simplex virus 1 alkaline nuclease is required for efficient egress of capsids from the nucleus. Virology 196146-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strobel-Fidler, M., and B. Fracike. 1980. Alkaline, deoxyribonuclease induced by herpes simplex virus type 1: composition and properties of the purified enzyme. Virology 103493-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas, M. S., M. Gao, D. M. Knipe, and K. L. Powell. 1992. Association between the herpes simplex virus major DNA-binding protein and alkaline nuclease. J. Virol. 661152-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Truscott, K. N., K. Brandner, and N. Pfanner. 2003. Mechanisms of protein import into mitochondria. Curr. Biol. 13R326-R337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaughan, P. J., L. M. Banks, D. J. Purifoy, and K. L. Powell. 1984. Interactions between herpes simplex virus DNA-binding proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 652033-2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wallace, D. C. 2005. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu. Rev. Genet. 39359-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weller, S. K., M. R. Seghatoleslami, L. Shao, D. Rowse, and E. P. Carmichael. 1990. The herpes simplex virus type 1 alkaline nuclease is not essential for viral DNA synthesis: isolation and characterization of a lacZ insertion mutant. J. Gen. Virol. 712941-2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.