Abstract

We investigated the prevalence, patterns, and correlates of past-year DSM-IV hallucinogen use disorders (HUDs) among past-year users of MDMA and other hallucinogens from a sample of Americans 18 or older (n = 37,227). Users were categorized as MDMA users and other hallucinogen users. Overall, one in five (20%) MDMA users and about one in six (16%) other hallucinogen users reported at least one clinical feature of HUDs. Among MDMA users, prevalence of hallucinogen abuse, subthreshold dependence, and dependence was 4.9%, 11.9%, and 3.6%, respectively. The majority with hallucinogen abuse displayed subthreshold dependence. Most with hallucinogen dependence exhibited abuse. Subthreshold hallucinogen dependence is relatively prevalent and represents a clinically important subgroup that warrants future research and consideration in a major diagnostic classification system.

BACKGROUND

The use and abuse of MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, or ecstasy) is a significant public health concern. In the United States, MDMA is classified as a hallucinogen, a category comprising LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), PCP (phencyclidine, or angel dust), peyote, mescaline, and psilocybin (mushrooms).1,2 During the past decade, rates of MDMA use and associated morbidity and mortality have risen in the United States and other countries.3–7 In the United States, the number of MDMA-related admissions to emergency departments (EDs) increased dramatically from 1994 to 2001.8 Recent national surveys also indicate that MDMA use among American adults aged 18–25 has increased,1 while the perception of risk arising from MDMA use among eighth graders has declined.9

MDMA is a potent neurotoxin in animals and appears to have long-lasting neurotoxic effects in humans.10–13 Brain imaging indicates that MDMA users are susceptible to MDMA-induced neuronal damage.14 Repeated use may lead to significant serotonin depletion, causing disturbances in mood, memory, and impulsiveness.10,11 However, little is known concerning whether there may be long-term alterations in neurotransmitter responses in humans that are associated with MDMA-induced serotonin neurotoxicity.13 Any potential efforts to investigate this issue would seem to present almost insuperable challenges. These may include ethical and legal proscriptions against repeatedly administering MDMA in a controlled study, as well as frequent polydrug use among this population, and difficulties in determining their premorbid cognitive and psychological functioning.15

MDMA use is associated with depression, anxiety, elevated impulsiveness, and memory deficits; depending on prior levels of MDMA and other substance use, these symptoms may persist after cessation.10–12 The use of hallucinogens other than MDMA has received much less research attention. However, published studies have found that, as with MDMA,16–18 the use of other hallucinogens is associated with regular cigarette smoking, alcohol use, depression, and risky sexual behaviors.19,20

Little is presently known about MDMA and other hallucinogen users who have subsequently developed abuse or dependence (ie, hallucinogen use disorders or HUDs) as specified by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM)-IV.21 To date, only a few studies have estimated the prevalence of HUDs. Data from the 1990–1992 National Comorbidity Study indicate that 5% of all respondents aged 15–54 who reported a history of hallucinogen use met criteria for DSM-III-R hallucinogen dependence over the course of their lives.22 In the 1992 National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey and the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 0.6% and 1.7% of all adult respondents, respectively, met criteria for lifetime hallucinogen abuse or dependence, as defined by the DSM-IV.23,24 In the 2000–2001 National Household Surveys on Drug Use, 2–3% of hallucinogen users who reported first use of any hallucinogen within the past 24 months met criteria for past-year hallucinogen dependence.25 However, previous studies have not examined the characteristics of hallucinogen users with past-year HUDs,22–24 and Stone et al.25 did not examine hallucinogen abuse.

MDMA is somewhat different from other hallucinogens: it is a hallucinogenic stimulant and has potentially neurotoxic effects. Additionally, MDMA users are likely to use multiple illicit substances26–28 and may have a high prevalence of HUDs.29 Given the scarce data on HUDs and the increased use of MDMA, it is important to understand the extent and characteristics of individuals with past-year HUDs.

This study examines, within a nationally representative sample of past-year hallucinogen users, the clinical features of past-year HUDs among MDMA users compared with users of other hallucinogens, as well as the prevalence and correlates of hallucinogen abuse and dependence. Given the lack of research on the prevalence of individuals who met criteria for one or two symptoms of dependence but did not meet criteria for a full diagnosis (“subthreshold dependence,” sometimes called “diagnostic orphans”), as well as those who met criteria for dependence but did exhibit symptoms of abuse,30,31 we also examine subthreshold dependence and the co-occurrence of symptoms of abuse and dependence. While studies have revealed that diagnostic orphans among marijuana users are as likely as individuals with a marijuana use disorder to abuse other drugs,31 little is presently known about diagnostic orphans among hallucinogen users. Findings from our study are likely to shed new light on the extent of HUDs among recent hallucinogen users and thus have implications for the next iteration of the DSM.

METHODS

Data Source

This study is based on data from the public use file of the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).32 The NSDUH provides population estimates of substance use and related disorders in the United States, utilizing multistage area probability sampling methods to select a representative sample of the civilian, non-institutionalized population aged 12 years or older. Participants include household residents; residents of shelters, rooming houses, and group homes; residents of Alaska and Hawaii; and civilians residing on military bases. To improve the precision of drug use estimates for key subgroups, adolescents and young adults aged 12–25 years were oversampled.

NSDUH participants were interviewed in private at their place of residence and were assured that their names would not be recorded and that their responses would be kept strictly confidential. Interviewers signed confidentiality agreements, and consent forms thoroughly described data collection procedures and protections.

The NSDUH interview uses computer-assisted interviewing (CAI) to increase the validity of respondents’ reports of illicit drug use behaviors.33 CAI methodology combines computer-assisted personal interviewing and audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI). ACASI provides respondents with a highly private and confidential setting in which to answer sensitive questions. Questions were either displayed on a computer screen or read through headphones to respondents, who entered answers directly into the computer.

A total of 68,308 respondents aged 12 years or older completed the interview during the period from January through December of 2005. Weighted response rates for household screening and interviewing were 91.3% and 76.2%, respectively. NSDUH design and data collection procedures have been previously reported in detail.32

Analysis Sample

A total of 37,227 adults aged 18 or older were identified from the public use data file of the 2005 NSDUH, of which 52% were women, 31% were young adults 18–34 years, and 30% were members of non-white groups (African American, 11%;Hispanic, 13%; American Indian or Alaska Native, 0.5%; Asian or other Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian, 4.5%; and persons reporting multiple race or ethnicity, 1%).

Study Variables

Hallucinogen Use Variables

NSDUH assessments of drug use were conducted via ACASI and included detailed descriptions of different types of drugs. The survey specifically assessed lifetime use of the following categories of hallucinogens: LSD, PCP, peyote, mescaline, psilocybin, and MDMA (ecstasy). Respondents also reported age of first use (onset) of any hallucinogen, number of days using hallucinogen(s) in the past 12 months, and recency of any hallucinogen use. We categorized past-year hallucinogen users (any hallucinogen use within 12 months prior to the interview) into two mutually exclusive groups: MDMA users (regardless of whether they had used any other type of hallucinogens), and other hallucinogen users (LSD, PCP, peyote, mescaline, or psilocybin) who had not used MDMA within this period. Number of days that respondents used any hallucinogens in the past year was categorized into four groups: 1–5 days (ie, experimental use), 6–11 days (infrequent), 12–51 (approximately monthly), and 52 or more days (approximately weekly use or more). The survey did not assess the number of days that respondents had consumed any specific type of hallucinogen in the past year.

Past-year HUDs were assessed by standardized questions as specified by DSM-IV criteria.21 The four clinical features of past-year abuse are as follows:

serious problems at home, work, or school caused by using hallucinogens;

regular consumption of a hallucinogen that put the user in physical danger;

repeated use of hallucinogens that caused the user to get in trouble with the law; and

problems with family or friends caused by the continued use of hallucinogens.

The following six past-year clinical features of hallucinogen dependence were also assessed:

spending a great deal of time over the course of a month getting, using, or getting over effects of hallucinogens;

using hallucinogens more often than intended or being unable to maintain limits on use;

using the same amount of hallucinogens with decreasing effects or increasing use to get the same desired effects as previously attained;

inability to reduce or stop hallucinogen use;

continued hallucinogen use despite problems with emotions, nerves, or mental or physical health; and

reduced involvement or participation in important activities because of hallucinogen use.

The “withdrawal” criterion was not specified to be present for hallucinogen dependence by the DSM-IV21 and was thus not assessed by the survey.

Consistent with the DSM-IV,21 respondents who met at least one of the hallucinogen abuse criteria but did not meet criteria for hallucinogen dependence in the past year were classified as exhibiting hallucinogen abuse. Hallucinogen dependence included respondents who met criteria for at least three hallucinogen dependence symptoms in the past year, regardless of hallucinogen abuse. Subthreshold dependence (“diagnostic orphans”) included respondents who met 1 to 2 hallucinogen dependence criteria, but did not meet criteria for dependence or abuse. Lifetime HUDs were not assessed by the survey. Due to the very large scale of the national survey, diagnoses of HUDs were not validated by clinicians.

Social and Demographic Variables

We examined associations of HUDs with the following demographics: age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, current employment status, current marital status, total annual family income, and population density where the respondent resided (large metropolitan areas, population ≥1 million; small metropolitan areas, population <1 million; and non-metropolitan areas, outside a standard metropolitan statistical area).

Other Substance Use Variables

Past-year alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine use disorders (abuse or dependence) were also assessed with reference to DSM-IV criteria. Nicotine dependence was defined according to the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (NDSS)34 and the Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence (FTND).35,36 Nicotine dependence was present if the respondent’s average NDSS score was 2.75 or higher. Based on the FTND and consistent with NSDUH protocols, we also specified nicotine dependence as present if respondents reported that they had smoked any cigarettes in the past month and had their first cigarettes within 30 minutes of awakening.

Mental Heath, Criminality, HIV Risk, and ED Treatment Variables

Anxiety disorder was assessed by the question, Has a doctor or other medical professional told you that you had anxiety disorder in the past year? Questions assessing major depressive episodes were based on DSM-IV criteria and adapted from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication.37 In NSDUH, no exclusions were made for major depressive episodes caused by medical illness, bereavement, or substance use disorders. Past-year criminal activity was defined as an arrest or booking for breaking the law(excluding minor traffic violations) during the past 12 months.38 HIV risk variables included injection drug use and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). History of injection drug use was defined as lifetime use of a needle to inject a substance (eg, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, or other stimulants) that was not prescribed for the respondent, or that was consumed only for the experience or feeling it caused.39 Past-year STDs were assessed by the question, Has a doctor or other medical professional told you that you had a sexually transmitted disease in the past year? STDs include chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes, and syphilis. Past-year ED admission was defined as having been treated in an ED during the past 12 months.40

Data Analysis

We first examined the prevalence of hallucinogen use among all adults (N = 37,227) and assessed demographic characteristics of the subset of adults reporting past-year hallucinogen use (N = 1,341). We then examined patterns of hallucinogen use and clinical characteristics of HUDs. Bivariate associations were examined with χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. We conducted multinomial logistic regression procedures to identify characteristics associated with reports of clinical features of HUDs and respondents’ category of diagnoses, using SUDAAN software41 for the analyses. All estimates presented here are weighted except for sample sizes, which are unweighted.

RESULTS

Overall, 1.4% (N = 1,341) of all adults reported use of at least one type of hallucinogen in the past year. Approximately 50% of all past-year hallucinogen users (0.7% of all adults) used MDMA during this period. The demographic characteristics of MDMA users (N = 652) generally resembled those of other hallucinogen users (N = 689; see Table 1). The majority of past-year MDMA users and other hallucinogen users were male (65% vs. 72%), aged 18–25 (64% vs. 73%), white (73% vs. 83%), had attended college (47% vs. 53%), were employed (72% vs. 76%), had never been married (79% vs. 83%), had an annual family income under $40,000 (56% vs. 60%), and resided in metropolitan areas (97% vs. 94%). MDMA users differed slightly from other hallucinogen users. Higher proportions of MDMA users identified themselves as African Americans (11% vs. 3%) and lived in large metropolitan areas (60% vs. 45%).

TABLE 1.

Selected demographic characteristics of past-year MDMA and other hallucinogen users aged 18 and older (unweighted N = 1,341)

| Proportion, column % | MDMA users n = 652 | Other hallucinogen users n = 689 |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 64.7 | 71.9 |

| Female | 35.3 | 28.9 |

| Age group in years | ||

| 18–25 | 64.1 | 72.8 |

| 26–34 | 23.3 | 15.9 |

| 35 or older | 12.6 | 11.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 72.9 | 83.0‡ |

| African American | 11.3 | 2.9 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.7 | 2.4 |

| Asian, Pacific Islander, or Native Hawaiian | 2.7 | 1.2 |

| Multiple race or ethnicity | 2.0 | 1.1 |

| Hispanic | 10.5 | 9.4 |

| Educational level | ||

| Less than high school | 19.0 | 19.2 |

| High school graduate | 33.8 | 28.4 |

| College or more | 47.2 | 52.5 |

| Employment status | ||

| Not employed or not in the work force | 20.0 | 14.0 |

| Unemployed or laid off | 8.2 | 9.7 |

| Employed | 71.8 | 76.3 |

| Current marital status | ||

| Never been married | 78.9 | 82.7 |

| Separated, divorced, or widowed | 9.5 | 4.8 |

| Married | 11.6 | 12.5 |

| Family income | ||

| $0–$19,999 | 31.3 | 33.5 |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 24.5 | 26.1 |

| $40,000–$74,999 | 23.3 | 21.2 |

| $75,000+ | 20.9 | 19.2 |

| Population density | ||

| Large metro areas | 59.7 | 44.6* |

| Small metro areas | 37.2 | 49.8 |

| Non-metro areas | 3.1 | 5.6 |

χ2 test for hallucinogen use and each demographic variable

p ≤ 0.01

p ≤ 0.001.

Patterns of Hallucinogen Use

Among past-year MDMA users, 12% reported LSD use and 3% reported PCP use in the past year. MDMA users reported lifetime consumption of more types of hallucinogens than other hallucinogen users (2.8 [SE = 0.12] vs. 2.2 [SE = 0.09] types). The majority of MDMA (56%) and other hallucinogen (72%) users had used hallucinogens on fewer than six days in the last year, and 10% of MDMA users and 7% of other hallucinogen users had used hallucinogens on 6–11 days. MDMA users were more likely than other hallucinogen users to use hallucinogens on 12 or more days (34% vs. 22%).

There were no differences between groups in age of first use of any hallucinogen (mean: 18.6 years [SE = 0.36] vs. 18.2 years [SE = 0.29]). In each group, 53% reported first use of any hallucinogen at adulthood (age 18 or older). Most past-year MDMA users (76%) also first used MDMA at adulthood.

Symptom Profile of Hallucinogen Users

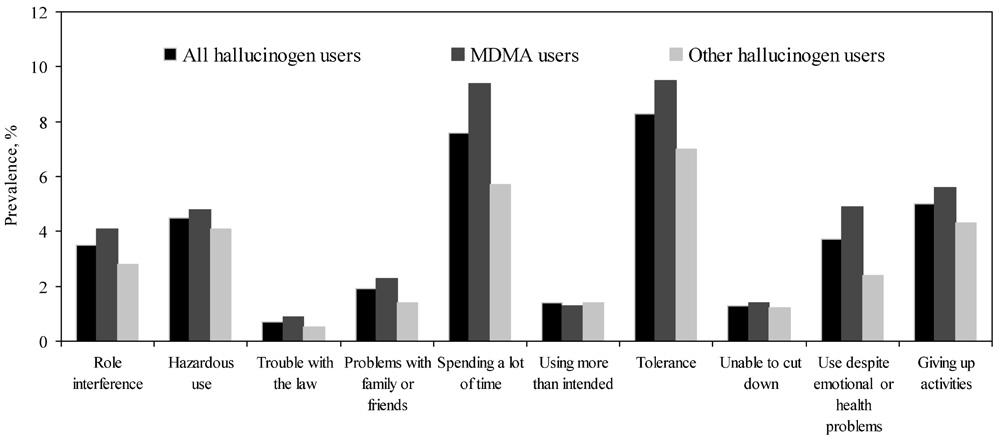

The symptom profile of MDMA users resembled that of other hallucinogen users (see Figure 1). “Spending a lot of time using or getting over the effects of hallucinogens” and “tolerance” were two symptoms commonly presented by users; each was reported by approximately 10% of MDMA users and 6–7% of other hallucinogen users.

FIGURE 1.

Prevalence of DSM-IV hallucinogen abuse or dependence symptoms among past-year hallucinogen users aged 18 and older in the 2005 NSDUH (unweighted N = 1,341).

There was a very low prevalence of reports of symptoms related to “having trouble with the law because of hallucinogen use” (less than 1% of hallucinogen users). The only clinical symptom that distinguished the groups was “continued hallucinogen use despite having emotional or health problems,” which was slightly more common among MDMA users (5% vs. 2%).

HUD Prevalence

The prevalence of HUDs among all respondents was fairly low; 0.07% met criteria for abuse and 0.04% for dependence. However, symptoms of HUDs were common in the subsample of respondents who reported hallucinogen use in the past year: 20% of MDMA users and 16% of other hallucinogen users reported one or more symptoms of HUDs.

As shown in Table 2, we classified respondents reporting any HUD symptoms into three groups:

hallucinogen abuse without a dependence diagnosis (4.9%),

subthreshold dependence (1–2 dependence criteria) without abuse (10.3%), and

a dependence diagnosis regardless of abuse (2.9%).

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of past-year DSM-IV hallucinogen use disorders among past-year hallucinogen users aged 18 and older (unweighted N= 1,341)

| Hallucinogen use disorder | Abuse | Subthreshold dependence | Dependence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of disorder | With subthreshold dependence |

Without subthreshold dependence |

Without symptoms of abuse |

With symptoms of abuse |

Without symptoms of abuse |

| Prevalence, % (SE) | |||||

| Overall | 3.3 (0.76) | 1.6 (0.49) | 10.3 (1.13) | 2.1 (0.67) | 0.8 (0.28) |

| MDMA users | 3.3 (0.87) | 1.6 (0.85) | 11.9 (1.73) | 2.4 (0.89) | 1.2 (0.47) |

| Other hallucinogen users | 3.3 (1.21) | 1.6 (0.55) | 8.7 (1.72) | 1.8 (0.81) | 0.4 (0.30) |

χ2 test for MDMA users vs. other hallucinogen users: none was significant.

Abbreviation: SE = standard error.

Additionally, we relaxed the DSM-IV binary distinction for abuse and dependence and examined the co-occurrence of abuse and dependence. Of MDMA users, 3.3% met criteria for both abuse and subthreshold dependence, 1.6% met criteria for abuse only (without subthreshold dependence), 2.4% met criteria for dependence with abuse symptoms, and 1.2% met criteria for dependence only (ie, no concomitant symptoms of abuse). The majority of MDMA users (67%; 3.3% out of 4.9%) with hallucinogen abuse also exhibited subthreshold dependence, and the majority of them (67%; 2.4% out of 3.6%) with hallucinogen dependence also reported abuse symptoms. A similar pattern was found among users of other hallucinogens.

Number of Criterion Symptoms by Diagnosis

Among MDMA users, the abuse-only group and the subthreshold dependence-only group, on average, reported one symptom (see Table 3); and the abuse with subthreshold dependence group reported a mean of 2.9 symptoms, a number similar to the dependence only group (3.6 symptoms). MDMA users who were classified as dependent and who also manifested symptoms of abuse had the highest mean number (6.4) of symptoms. A similar pattern was also observed among users of other hallucinogens.

TABLE 3.

Mean number of the ten DSM-IV hallucinogen abuse or dependence symptoms endorsed by past-year hallucinogen users aged 18 and older, by category of diagnosis (unweighted N = 1,341)

| Hallucinogen use disorder | Adults with abuse |

Adults with subthreshold dependence |

Adults with dependence |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of disorder | With subthreshold dependence |

Without subthreshold dependence |

Without symptoms of abuse |

With symptoms of abuse |

Without symptoms of abuse |

| Unweighted n | 46 | 19 | 139 | 28 | 14 |

| Mean number of 10 DSM-IV symptoms (SE) | |||||

| Overall | 2.7 (0.18) | 1.1 (0.08) | 1.1 (0.03) | 6.1 (0.39) | 3.4 (0.21) |

| MDMA users | 2.9 (0.24) | 1.0 (0.00) | 1.1 (0.04) | 6.4 (0.40) | 3.6 (0.24) |

| Other hallucinogen users | 2.4 (0.18) | 1.1 (0.15) | 1.1 (0.04) | 5.6 (0.54) | 3.0 (0.00) |

T test for MDMA users vs. other hallucinogen users: none was significant.

Abbreviation: SE = standard error.

Correlates of DSM-IV Hallucinogen Abuse, Subthreshold Dependence, and Dependence

Table 4 summarizes results from multinomial logistic regression of correlates of hallucinogen abuse (without dependence), subthreshold dependence (without abuse), and dependence (regardless of abuse) based on the DSM-IV classification. The odds of being in a category of diagnosis were each compared with hallucinogen users without any HUD symptoms. Because of the low prevalence of abuse and dependence, we conducted these analyses on all hallucinogen users and included a binary covariate indicating the type of hallucinogens used (MDMA vs. other hallucinogens), which was found to be unassociated with any of the three diagnostic categories examined. We included all covariates found to be significant from bivariate analyses in the adjusted model (see Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Multinominal logistic regression analysis of past-year hallucinogen use disorder among past-year hallucinogen users aged 18 and older (unweighted N= 1,341)

| Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs)|| |

Abuse without dependence# |

Subthreshold dependence without abuse# |

Dependence regardless of abuse# |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (vs. 26–34 years) | |||

| 18–25 | 1.0 (0.33 – 2.92) | 0.8 (0.40 – 1.45) | 5.7 (0.97 – 33.38)† |

| 35 or older | 1.4 (0.26 – 7.28) | 0.1 (0.01 – 2.19) | 0.2 (0.01 – 3.92) |

| Race/ethnicity (vs. White) | |||

| African American | 1.5 (0.49 – 4.56) | 0.4 (0.11 – 1.52) | 1.6 (0.41 – 6.05) |

| Hispanic | 1.6 (0.59 – 4.17) | 0.6 (0.31 – 1.30) | 1.2 (0.18 – 8.72) |

| Other | 6.9 (1.97 – 24.31)‡ | 2.3 (0.89 – 5.71)† | 1.1 (0.17 – 7.68) |

| Family income (vs. $75,000+) | |||

| $0–$19,999 | 0.5 (0.21 – 1.24) | 2.8 (1.45 – 5.40)‡ | 0.3 (0.09–0.91)* |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 0.8 (0.31 – 2.00) | 3.4 (1.07 – 5.22)* | 0.5 (0.12 – 2.45) |

| $40,000–$74,999 | 0.8 (0.31 – 2.00) | 3.9 (1.95 – 7.76)‡ | 1.8 (0.52 – 5.82) |

| Number of days using hallucinogens (vs. 6–11 days) | |||

| 1–5 | 1.8 (0.42 – 7.75) | 0.3 (0.13 – 0.73)‡ | 0.1 (0.02 – 0.69)* |

| 12–51 | 6.0 (1.50 – 24.09)‡ | 1.6 (0.64 – 4.18) | 6.7 (2.19 – 20.74)‡ |

| 52 or more days | 4.3 (0.96 – 19.97)† | 1.6 (0.53 – 4.99) | 7.4 (1.20 – 45.15)* |

| Age of first hallucinogen use (vs. Age 18 or older) | |||

| Age 17 or younger | 1.8 (0.95 – 3.33)† | 1.5 (0.83 – 2.53) | 1.1 (0.38 – 2.96) |

| Major depressive episode (vs. No) | |||

| Yes | 1.7 (0.78 – 3.78) | 4.2 (2.42 – 7.41)§ | 4.4 (1.70 – 11.41)‡ |

| Booked/arrested (vs. No) | |||

| Yes | 0.9 (0.41 – 1.80) | 0.3 (0.18 – 0.65)‡ | 0.8 (0.34 – 1.89) |

| Marijuana use disorder (vs. No) | |||

| Yes | 5.9 (2.69 – 12.82)§ | 1.8 (0.98 – 3.47)† | 2.6 (1.02 – 6.70)* |

| Past-year STD (vs. No) | |||

| Yes | 8.0 (1.88 – 34.03)‡ | 4.1 (1.30 – 12.84)* | 1.2 (0.13 – 10.23) |

| Past-year ED treatment (vs. No) | |||

| Yes | 2.2 (1.19 – 3.95)* | 1.2 (0.64 – 2.05) | 1.1 (0.45 – 2.48) |

Characteristics tested but excluded from the adjusted model because they were not significant include sex, education, employment status, marital status, population density, onset of MDMA use, type of hallucinogens used, anxiety, nicotine dependence, cocaine use disorder, alcohol use disorder, and injection drug use.

p ≤ 0.05

p <0.09

p ≤ 0.01

p ≤ 0.001.

The adjusted logistic regression model included variables listed in that specific column.

The comparison group included hallucinogen users who did not report any symptoms of hallucinogen abuse or dependence.

Abuse

As compared with others (Native Americans, Asians/Pacific Islanders/Native Hawaiians, and multiple race/ethnicity), whites were less likely to abuse hallucinogens. Past-year use of hallucinogens on 12 to 51 days, past-year marijuana use disorder, past-year STD, and past-year ED admission were all associated with increased odds of abuse. For example, hallucinogen users with a past-year STD were eight times more likely than those without an STD to meet criteria for abuse.

Subthreshold Dependence

Family income under $75,000, past-year major depressive episodes, past-year marijuana use disorder, and past-year STD were associated with increased odds of subthreshold dependence. On the other hand, the experimental use of hallucinogens (fewer than six days in the previous year) and past-year arrest were associated with decreased odds of subthreshold dependence.

Dependence

Use of hallucinogens on 12 or more days in the past year, past-year major depressive episodes, and past-year marijuana use disorder were associated with increased odds of dependence, whereas a family income under $20,000 compared with a family income $75,000 or more was associated with reduced odds of dependence.

DISCUSSION

This study examined specific diagnostic patterns and characteristics of HUDs among past-year or active hallucinogen users in a large, nationally representative sample. An estimated 1.4% of non-institutionalized American adults had used hallucinogens in the past year, and approximately half of them had used MDMA in the past year. The prevalence of past-year HUDs among all respondents was fairly low (less than 1%). However, almost one-fifth of past-year hallucinogen users reported at least one clinical feature of HUDs, serving as a reminder of the importance in clinical settings of screening hallucinogen users for HUD symptoms.

MDMA users generally resembled other hallucinogen users in demographics: the majority of both groups were young, white, male, employed, and educated. Patterns of past-year HUDs among MDMA users also are similar to other hallucinogen users. The only clinical feature that distinguished the groups was that MDMA users were slightly more likely to continue using hallucinogens despite emotional or health problems, which may be related to MDMA’s potential neuropsychological effects and MDMA users’ greater involvement with hallucinogens. Consistent with the findings of Cottler et al.,29 we found that “spent a lot of time getting over the effects of hallucinogens” and “tolerance” were more commonly endorsed symptoms than others.

The patterns of HUDs deserve attention. The DSM-IV21 assumes a severity continuum between abuse and dependence and specifies a hierarchical distinction between them. Individuals assigned to the “abuse” category must not meet criteria for “dependence,” and abuse is often left unidentified among individuals with dependence. Hence, little is known about the co-occurrence of symptoms of abuse and dependence. By relaxing this hierarchical assumption, we found that 72% of adults with hallucinogen dependence also reported abuse symptoms (2.1% out of 2.9%). These users, who can be considered a subgroup with the most severe hallucinogen use problems, reported six criteria symptoms on average and accounted for 2.1% of all users. Additionally, 33% and 18% of MDMA and other hallucinogen users with dependence, respectively, did not report any abuse symptoms. Hence, studies of drug use disorders and clinical practices that use the presence of abuse as a screening method to identify cases of drug dependence may miss dependent cases.42

Two-thirds of MDMA or other hallucinogen users with abuse (3.3% out of 4.9%) also reported 1–2 dependence criteria and, on average, reported 2.7 symptoms. Given that this abuse group (3.3%) is as prevalent as the whole dependence group (2.9%), further attention should be paid to determining appropriate clinical courses and treatment needs among MDMA or other hallucinogen abusers with subthreshold dependence. We also found a comparatively large proportion of users who reported 1–2 dependence criteria and did not belong to a DSM-IV diagnosis (12% and 9% of past-year MDMA and other hallucinogen users). These “diagnostic orphans” reported, on average, a similar number of symptoms (one) as the abuse only group. Data from this study cannot address whether diagnostic orphans are at an early stage of dependence or represent a distinct, less severe subgroup of hallucinogen users. However, consistent with previous findings concerning diagnostic orphans pertinent to marijuana users,31 an exclusive reliance by clinicians on diagnoses consistent with the DSM-IV would overlook hallucinogen users who perceive problems associated with hallucinogen use (ie, those with one or two symptoms of dependence). Together, our results support the utility of integrating dimensional and categorical diagnostic criteria for classifying substance use disorders in the upcoming DSM-V.43

In this sample, HUDs are linked with increased days of hallucinogen use but are unassociated with age of initial hallucinogen use. Prior studies have suggested that MDMA/hallucinogen users are likely to use other drugs as well.20,26,44 We found that past-year marijuana use disorder was associated with hallucinogen abuse and dependence, suggesting concurrent abuse of these substances. In contrast, past-year tobacco, cocaine, and alcohol use disorders did not distinguish hallucinogen users by diagnosis. The association of past-year STDs with abuse and subthreshold dependence is also noteworthy, and it supports prior findings that suggest the co-occurrences of MDMA/hallucinogen use and risky sexual behaviors.18,20

Further, DSM-IV abuse criteria reflect consequences of drug use, while dependence criteria capture behavioral and physiological symptoms of use. We found that the abuse group had increased odds of past-year ED admissions and that the two dependence groups had increased odds of manifesting major depressive episodes, which were independent of the influence of a past-year marijuana use disorder. It should be noted that the association between MDMA use and depression is influenced by multiple factors, including MDMA’s neurotoxic effects, self-medication of negative affect, effects of other substance abuse, and preexisting psychopathology.45–48

Many adult MDMA and other hallucinogen users may believe that they suffered no adverse effects from their use. Less than 1% reported having gotten into trouble with law due to their hallucinogen use, and only about 1.3% reported being unable to reduce use. Hendrickson and Gerstein49 found that MDMA users were less likely to be arrested for violent crimes, but more likely to be arrested for crimes related to the sale of drugs other than MDMA. This observation may also be related to the nature of our sample as incarcerated individuals are not covered by the NSDUH.

Finally, we found some variations in HUDs by race/ethnicity and family income. By disaggregating the “other” race/ethnicity category, we found a higher prevalence of hallucinogen abuse among Asians/Pacific Islanders/Native Hawaiians (23.8%) and members of multiple race/ethnicity (11.0%) compared with whites (4.1%). Hallucinogen users in the highest level of family income had lower odds of subthreshold dependence than those in the lower levels of family income. However, abuse was unassociated with the level of family income, and those in the highest level of family income had higher odds of dependence than those in the lowest level. These findings suggest that abuse, subthreshold dependence, and dependence appear to have affected different subgroups of hallucinogen users.

Limitations and Strengths

Our findings should be interpreted with caution. First, due to the NSDUH’s cross-sectional design, causality cannot be inferred from our findings. Second, the survey relies on respondents’ self-reports, and is subject to biases associated with memory errors and social desirability (unwillingness to disclose drug use), and older adults may be more likely than younger ones to be affected by memory errors. Underreports of drug use have been noted in household surveys.50

Third, individuals who were institutionalized or homeless at the time of the survey were not included, and those who suffered severe consequences from hallucinogen use (cognitive or psychiatric disorders) might not have been domiciled or been otherwise unable to participate.

Fourth, diagnoses of HUDs and other disorders were assessed by standardized questions administered by trained interviewers and were not validated by clinicians. In addition, the hallucinogen category includes various substances that act on cognition and sensation through multiple mechanisms, thus making broad conclusions about their adverse effects challenging. Finally, like other large surveys, the NSDUH does not collect data on the cumulative dosage and purity of MDMA tablets taken by users. MDMA-induced psychiatric consequences are influenced by dosage taken.51 Bogus MDMA tablets (eg, ketamine, LSD, methamphetamine, paramethoxyamphetamine, and dextromethorphan) also affect drug use behaviors and consequences.52,53 Parrott53 reviewed the literature and concluded that problems related to the purity of MDMA were salient during the 1990s and that by the early 2000s, high-dose MDMA tablets were more common.

In addition to these limitations, the NSDUH dataset has noteworthy strengths. The sample is representative of the non-institutionalized adult population in the United States. The NSDUH is currently the largest population-based survey in the United States and yields the largest sample of past-year or active adult MDMA and other hallucinogen users. Additionally, the survey’s ACASI methodology increases respondents’ reporting of socially stigmatized or sensitive drug use behaviors.33

Implications and Conclusions

We identified several subgroups of hallucinogen users who reported symptoms of HUDs: abuse only, subthreshold dependence only, abuse in conjunction with subthreshold dependence, dependence only, and dependence in conjunction with abuse symptoms. These findings suggest heterogeneity among past-year MDMA/hallucinogen users. In addition to relying on DSM-IV classifications, a compilation of all symptoms may better describe the severity of problems resulting from hallucinogen use. The exclusive reliance on DSM-IV definitions may overlook a group of “diagnostic orphans” who could benefit from early interventions. Diagnostic orphans of hallucinogen users had increased odds of past-year STDs and major depressive episodes, and they warrant future study.

Finally, 2.4% of past-year MDMA users exhibited serious dependence, reporting an average of 6.4 criteria symptoms. Repeated MDMA use is of concern, given the likely consequences of neuronal damage, memory impairment, and psychiatric disorders.11–14 The most recent national survey reveals an increase of MDMA use among young American adults.1 Clearly, effective focused prevention and treatment interventions are needed to target at-risk subgroups in order to reduce MDMA use and its clinical consequences.

Acknowledgments

Ashwin A. Patkar has received grant support from Pfizer, Forest Laboratories, Cephalon, and Titan Pharmaceuticals, and is on the speakers’ bureaus of Cephalon and Reckitt- Benckiser. Paolo Mannelli has received research funding from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, McNeil Consumer and Specialty, Organon, Orphan Medical, Pfizer, Reckitt Benckiser, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

This work was supported by grants DA019623 and DA019901 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, Md (Dr. Wu). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive and the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research provided the public use data files for NSDUH, which was sponsored by SAMHSA’s Office of Applied Studies.

We thank Jonathan McCall for proofreading the paper.

Footnotes

The opinions expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors, not of any sponsoring agency.

The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, Md.: Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Accessed October 15, 2007];National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, Survey Questionnaire Index, Wave 1. 2007 Available at: http://niaaa.census.gov/questionaire.html.

- 3.Cregg MT, Tracey JA. Ecstasy abuse in Ireland. Ir Med J. 1993;86:118–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel MM, Wright DW, Ratcliff JJ, Miller MA. Shedding new light on the “safe” club drug: Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy)-related fatalities. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:208–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schifano F, Oyefeso A, Corkery J, et al. Death rates from ecstasy (MDMA, MDA) and polydrug use in England and Wales 1996–2002. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:519–524. doi: 10.1002/hup.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuster P, Lieb R, Lamertz C, Wittchen HU. Is the use of ecstasy and hallucinogens increasing? Results from a community study. Eur Addict Res. 1998;4:75–82. doi: 10.1159/000018925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkins C, Bhatta K, Pledger M, Casswell S. Ecstasy use in New Zealand: Findings from the 1998 and 2001 National Drug Surveys. N Z Med J. 2003;116:U383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville, Md: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; Club Drugs, 2001 Update. 2001

- 9.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings. Bethesda, Md: National Instituteon Drug Abuse; 2007. NIH Publication No 07-6202. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montoya AG, Sorrentino R, Lukas SE, Price BH. Long-term neuropsychiatric consequences of “ecstasy” (MDMA): A review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2002;10:212–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parrott AC. Human psychopharmacology of ecstasy (MDMA): A review of 15 years of empirical research. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2001;16:557–577. doi: 10.1002/hup.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2006. MDMA (Ecstasy) Abuse. NIDA Research Report Series. [Accessed October 15, 2007];2007 Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/PDF/RRmdma.pdf.

- 13.Gudelsky GA, Yamamoto BK. Actions of 3,4-methylenedi-oxymethamphetamine(MDMA) on cerebral dopamineric, serotonergic and cholinergic neurons. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.10.003. [E-pub] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reneman L, Booij J, Majoie CB, Van Den Brink W, Den Heeten GJ. Investigating the potential neurotoxicity of ecstasy (MDMA): An imaging approach. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2001;16:579–588. doi: 10.1002/hup.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klugman A, Gruzelier J. Chronic cognitive impairment in users of ‘ecstasy’ and cannabis. World Psychiatry. 2003;2:184–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyd CJ, McCabe SE, d’Arcy H. Ecstasy use among college undergraduates: Gender, race and sexual identity. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24:209–215. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klitzman RL, Greenberg JD, Pollack LM, Dolezal C. MDMA (‘ecstasy’)use, and its association with high risk behaviors, mental health, and other factors among gay/bisexual men in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66:115–125. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strote J, Lee JE, Wechsler H. Increasing MDMA use among college students: Results of a national survey. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:64–72. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker A, Kochan N, Dixon J, Wodak A, Heather N. Drug use and HIV risk-taking behaviour among injecting drug users not currently in treatment in Sydney, Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;34:155–160. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rickert VI, Siqueira LM, Dale T, Wiemann CM. Prevalence and risk factors for LSD use among young women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2003;16:67–75. doi: 10.1016/s1083-3188(03)00012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anthony JC, Warner LA, Kessler RC. Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, controlled substances, and inhalants: Basic findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1994;2:244–268. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Compton WM, Conway KP, Stinson FS, Colliver JD, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of DSM-IV antisocial personality syndromes and alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:677–685. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grant BF. DSM-IV, DSM-III-R, and ICD-10 alcohol and drug abuse/harmful use and dependence, United States, 1992: A nosological comparison. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1481–1488. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone AL, Storr CL, Anthony JC. Evidence for a hallucinogen dependence syndrome developing soon after onset of hallucinogen use during adolescence. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2006;15:116–130. doi: 10.1002/mpr.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen W, Skrondal A. Ecstasy and new patterns of drug use: A normal population study. Addiction. 1999;94:1695–1706. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941116957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Topp L, Hando J, Dillon P, Roche A, Solowij N. Ecstasy use in Australia: Patterns of use and associated harm. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;55:105–115. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yacoubian GS., Jr Correlates of ecstasy use among students surveyed through the 1997 College Alcohol Study. J Drug Educ. 2003;33:61–69. doi: 10.2190/DVEE-3UML-2HDB-D4XV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cottler LB, Womack SB, Compton WM, Ben-Abdallah A. Ecstasy abuse and dependence among adolescents and young adults: Applicability and reliability of DSM-IV criteria. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2001;16:599–606. doi: 10.1002/hup.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saunders JB. Substance dependence and non-dependence in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD):Can an identical conceptualization be achieved? Addiction. 2006;101:48–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Degenhardt L, Lynskey M, Coffey C, Patton G. ‘Diagnostic orphans’among young adult cannabis users: Persons who report dependence symptoms but do not meet diagnostic criteria. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;67:205–212. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville, Md: Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services; Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. 2006

- 33.Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiffman S, Waters AJ, Hickcox M. The Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale: A multi-dimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:327–348. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fagerstrom KO. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav. 1978;3:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu LT, Schlenger WE, Galvin DM. Concurrent use of methamphetamine, MDMA, LSD, ketamine, GHB, and flunitrazepam among American youths. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu LT, Pilowsky DJ, Wechsberg WM, Schlenger WE. Injection drug use among stimulant users in a national sample. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:61–83. doi: 10.1081/ADA-120029866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu LT, Pilowsky DJ, Patkar AA. Non-prescribed use of pain relievers among adolescents in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN User’s Manual, Release 9.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hasin DS, Hatzenbueler M, Smith S, Grant BF. Co-occurring DSM-IV drug abuse in DSM-IV drug dependence: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helzer JE, van den Brink W, Guth SE. Should there be both categorical and dimensional criteria for the substance use disorders in DSM-V? Addiction. 2006;101:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jansen KL. Ecstasy (MDMA) dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;53:121–124. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daumann J, Hensen G, Thimm B, Rezk M, Till B, Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E. Self-reported psychopathological symptoms in recreational ecstasy(MDMA) users are mainly associated with regular cannabis use: further evidence from a combined cross-sectional/longitudinal investigation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;173:398–404. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1719-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lieb R, Schuetz CG, Pfister H, von Sydow K, Wittchen H. Mental disorders in ecstasy users: A prospective-longitudinal investigation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;68:195–207. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Medina KL, Shear PK. Anxiety, depression, and behavioral symptoms of executive dysfunction in ecstasy users: Contributions of poly drug use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soar K, Turner V, Parrott AC. Problematic versus non-problematic ecstasy/MDMA use: The influence of drug usage patterns and pre-existing psychiatric factors. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20:417–424. doi: 10.1177/0269881106063274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hendrickson JC, Gerstein DR. Criminal involvement among young male ecstasy users. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40:1557–1575. doi: 10.1081/JA-200066893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gfroerer J, Wright D, Kopstein A. Prevalence of youth substance use: The impact of methodological differences between two national surveys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47:19–30. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomasius R, Petersen KU, Zapletalova P, Wartberg L, Zeichner D, Schmoldt A. Mental disorders in current and former heavy ecstasy(MDMA) users. Addiction. 2005;100:1310–1319. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baggott M, Heifets B, Jones RT, Mendelson J, Sferios E, Zehnder c. Chemical analysis of ecstasy pills. JAMA. 2000;284:2190. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.17.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parrott AC. Is ecstasy MDMA? A review of the proportion of ecstasy tablets containing MDMA, their dosage levels, and the changing perceptions of purity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;173:234–241. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1712-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]