Abstract

Asymmetric localization of cell fate determinants is a crucial step in neuroblast asymmetric divisions. Whereas several protein kinases have been shown to mediate this process, no protein phosphatase has so far been implicated. In a clonal screen of larval neuroblasts we identified the evolutionarily conserved Protein Phosphatase 4 (PP4) regulatory subunit PP4R3/Falafel (Flfl) as a key mediator specific for the localization of Miranda (Mira) and associated cell fate determinants during both interphase and mitosis. Flfl is predominantly nuclear during interphase/prophase and cytoplasmic after nuclear envelope breakdown. Analyses of nuclear excluded as well as membrane targeted versions of the protein suggest that the asymmetric cortical localization of Mira and its associated proteins during mitosis depends on cytoplasmic/membrane-associated Flfl, whereas nuclear Flfl is required to exclude the cell fate determinant Prospero (Pros), and consequently Mira, from the nucleus during interphase/prophase. Attenuating the function of either the catalytic subunit of PP4 (PP4C; Pp4-19C in Drosophila) or of another regulatory subunit, PP4R2 (PPP4R2r in Drosophila), leads to similar defects in the localization of Mira and associated proteins. Flfl is capable of directly interacting with Mira, and genetic analyses indicate that flfl acts in parallel to or downstream from the tumor suppressor lethal (2) giant larvae (lgl). Our findings suggest that Flfl may target PP4 to the MIra protein complex to facilitate dephosphorylation step(s) crucial for its cortical association/asymmetric localization.

Keywords: Neuroblast, asymmetric division, PP4, Falafel

Drosophila neuroblasts (NBs) are stem-cell-like neural progenitors, which undergo repeated asymmetric divisions to self-renew and generate neurons and/or glia (for review, see Egger et al. 2008; Knoblich 2008). During each round of division the cell fate determinants Pros (a homeodomain-containing transcription regulator) (Doe et al. 1991; Vaessin et al. 1991), Numb (a negative regulator of Notch signaling) (Uemura et al. 1989; Rhyu et al. 1994), as well as Brain Tumor (Brat, whose mechanism of action in cell fate specification is unclear) (Bello et al. 2006; Betschinger et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2006b) are asymmetrically localized as protein crescents on the NB cortex. In the embryo, the NB mitotic spindle is oriented along the apicobasal axis, the cell fate determinants and their adapter proteins localize to the NB basal cortex and segregate exclusively to the smaller basal daughter, called ganglion mother cell (GMC). The GMC divides terminally to produce two neurons or glial cells. The coordination between the basal localization of the cell fate determinants and the apicobasal orientation of the spindle during mitosis is mediated by several evolutionarily conserved proteins that localize to the apical NB cortex during the G2 stage of the cell cycle. These comprise the Drosophila homologs of the Par3/Par6/aPKC protein cassette (Schober et al. 1999; Wodarz et al. 1999, 2000; Petronczki and Knoblich 2001), several proteins involved in heterotrimeric G protein signaling—Gαi/Partner of Inscuteable (Pins)/Locomotion defects (Loco) (Parmentier et al. 2000; Schaefer et al. 2000,2001; Yu et al. 2000, 2003, 2005)—as well as Inscuteable (Insc) (Kraut and Campos-Ortega 1996; Kraut et al. 1996). In contrast to the embryo, NBs in the larval central brain divide without an apparent fixed orientation. Nevertheless the majority of central brain NBs appear to utilize the same molecular machinery as embryonic NBs, with the apical and basal molecules sharing similar hierarchical relationships and localizing to opposite sides of the NB cortex.

Asymmetric localization of Pros and Brat on the one hand and Numb on the other, is mediated through direct interactions with their respective adapters, the coil–coil proteins Miranda (Mira) (Ikeshima-Kataoka et al. 1997; Shen et al. 1997; Schuldt et al. 1998) and Partner of Numb (Pon) (Lu et al. 1998). Although mutations affecting any of the apical proteins compromise asymmetric localization of basal proteins to varying extents, only in the case of aPKC has any mechanistic insight emerged. aPKC facilitates basal localization of cell fate determinants either through phosphorylation of the cytoskeletal protein Lgl and/or through direct phosphorylation of the determinant. Lgl is uniformly localized throughout the NB cortex, and is essential for cortical association and asymmetric localization of the cell fate determinants and their adapters (Ohshiro et al. 2000; Peng et al. 2000). aPKC phosphorylates Lgl on three conserved serine residues and the triphosphorylated form appears to be inactive due to a conformational change (Betschinger et al. 2003, 2005). The proposed model is that unphosphorylated, active Lgl is restricted to the basal cortex because of apically localized aPKC. Consistent with this model, a nonphosphorylatable version of Lgl, Lgl3A, in which the three target serines have been mutated to alanines, appears to be constitutively active and its expression leads to uniform cortical localization of the normally basally restricted cell fate determinants. Numb is a second protein that can be phosphorylated by aPKC (Smith et al. 2007) and phosphorylation of three N-terminal serines causes it to become cytoplasmic.

How Lgl acts to facilitate the localization of cell fate determinants is less clear. Lgl can bind nonmuscle Myosin II (Zipper) and genetic experiments suggest that Myosin II and Lgl have antagonistic activities. Hence, one possible scenario would be that Myosin II is active at the apical cortex due to the presence of phosphorylated Lgl, which is incapable of binding to Myosin II. Myosin II can then act to exclude basal proteins from the apical cortex (Barros et al. 2003). Alternatively, since yeast Lgl orthologs function in exocytosis, it has been suggested that Lgl might act by regulating this process (Wirtz-Peitz and Knoblich 2006). It is possible that Lgl positively promotes delivery and cortical association of the basal molecules, and that this is antagonized by Myosin II apically. In this scenario, Lgl is inhibited apically both by aPKC and Myosin II, and only basal Lgl is active and able to promote cortical association of the basal proteins.

The unconventional Myosin VI (Jaguar, Jar) and Myosin II bind in a mutually exclusive manner to the basal adapter protein Mira. However, in contrast to Myosin II, which acts antagonistically to Lgl, Jar acts in a synergistical manner with Lgl to effect Mira basal localization (Petritsch et al. 2003). In mitotic NBs devoid of Jar, Mira is mislocalized to the cytoplasm. Jar possibly mediates association of Mira with the basal actin cytoskeleton.

In addition to aPKC, a few other serine/threonine protein kinases have been shown to play a role in facilitating asymmetric protein localization in NBs. These include Cdk1 (Tio et al. 2001), required for the asymmetric localization of both apical and basal components during mitosis, Aurora A (AurA) (Lee et al. 2006a; Wang et al. 2006), and Polo (Wang et al. 2007), both of which mediate Numb and Pon asymmetric localization. With the exception of Polo kinase, which phosphorylates a serine residue within the Pon asymmetric localization domain, substrates for the other kinases have not been identified. The involvement of protein kinases in NB asymmetric divisions implies the involvement of protein phosphatases; however, to date, none have been implicated in the process.

In a clonal genetic screen designed to identify genes that mediate NB asymmetric divisions, we recovered multiple loss-of-function alleles of flfl. Falafel (Flfl) has been identified as a regulatory subunit of the evolutionarily conserved Protein Phosphatase 4 (PP4) Phosphatase complex (Gingras et al. 2005). PP4 belongs to the best-studied family of cellular protein serine/threonine phosphatases, PP2A (the other major families being PP1, PP2B, and PP2C) (Cohen 1989). Similarly to other PP2A-like phosphatases, PP4 functions as a heterotrimeric complex comprising of a catalytic subunit, PP4C (Helps et al. 1998), associated with two regulatory subunits, PP4R2 and PP4R3 (Gingras et al. 2005). PP4, or specifically PP4R3/Flfl, has been implicated in a variety of molecular and cellular processes including regulation of MEK/Erk (Yeh et al. 2004; Mendoza et al. 2005), insulin receptor substrate 4 (Mihindukulasuriya et al. 2004), Hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 (Zhou et al. 2004), and Histone deacetylase 3 (Zhang et al. 2005) activities, centrosome maturation (Sumiyoshi et al. 2002), cell cycle progression (Kittler et al. 2004), apoptosis (Mourtada-Maarabouni et al. 2003), DNA repair (Gingras et al. 2005), cell morphology (Kiger et al. 2003), and lifespan control (Wolff et al. 2006; Samuelson et al. 2007).

We show that loss of flfl, as well as attenuation of PP4C/Pp4-19C or PPR2/PPp4R2r function by RNAi specifically results in delocalization of Mira and its associated proteins throughout the cytoplasm in metaphase/anaphase NBs; in addition, both Mira and Pros localize to the NB nucleus prior to nuclear envelope breakdown. Excessive nuclear Mira is dependent on the presence of Pros. Our results suggest that whereas cytoplasmic or membrane-associated PP4 is required for asymmetric cortical localization of Mira (and its associated proteins) during metaphase and anaphase, nuclear PP4 is required to exclude Pros (and as a consequence, Mira) from the NB nucleus prior to nuclear envelope breakdown. Moreover, Flfl can complex with Mira in vivo and directly interact with Mira, suggesting that Flfl targets PP4 activity to the Mira complex to facilitate its correct localization.

Results

Disruption of flfl causes specific mislocalization of Mira and its associated proteins in mitotic and interphase NBs

In a clonal screen on third-instar larval (L3) brains, designed to identify novel genes on chromosome arm 3R required for NB asymmetric division (R. Sousa-Nunes, W. Chia, and W.G. Somers, unpubl.), we isolated a novel allele of flfl, flfl795. In metaphase and anaphase flfl795 clone NBs, Mira displays weak cortical crescents but also a pronounced mislocalization throughout the cytoplasm, whereas in surrounding heterozygous NBs Mira is localized to a robust crescent like in wild type with little cytoplasmic accumulation (Fig. 1A). As with many mutations that disrupt NB asymmetry during metaphase and anaphase, flfl795 NBs display telophase rescue: The majority of the cytoplasmic Mira relocalizes asymmetrically to the NB cortex at telophase, resulting in asymmetric segregation of Mira into the GMC (data not shown). Using the flfl795 allele, two additional alleles [flfl795(2), flfl795(3)] were identified via complementation screening of an independent collection of ethylmethane sulfonate (EMS) mutant stocks (Slack et al. 2006). Sequencing of these three EMS-induced flfl alleles revealed single point mutations resulting in premature stop codons at positions 324 (flfl795) and 630 [flfl795(2)] of the longest isoform (980 amino acids) and a disruption to the splice acceptor site at the 3′ end of the fourth intron [flfl795(3)] (Fig. 1B). All three alleles display a mislocalization of Mira to the cytoplasm of metaphase NBs and form an allelic series in terms of phenotypic severity: flfl795 > flfl795(3) > flfl795(2).

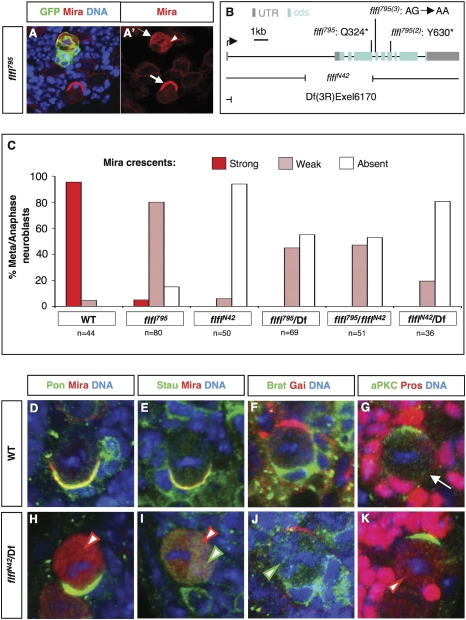

Figure 1.

Disruption of flfl causes mislocalization of all components of the Mira complex during metaphase and anaphase. (A) flfl mutant MARCM clone in an L3 brain. Clone is labeled with GFP and brain is further stained for Mira and DNA. Note: The NB is the largest cell in the clone. (A′) Red channel extracted from A. The metaphase NB in the clone has Mira throughout its cytoplasm (arrowhead outlined in red) and only a weak Mira crescent (thin white arrow), in contrast to the depicted anaphase NB outside the clone, which has a strong Mira crescent (thick white arrow). (B) Schematic of flfl locus and depiction of molecular lesions in the flfl795, flfl795(2), flfl795(3), and flflN42 alleles as well as the deficiency Df(3R)Exel6170, whose deletion removes the entire cds of flfl. (UTR) Untranslated region; (cds) coding sequence. (C) Quantification (percentage) of strong, weak and absent Mira crescents in dividing NBs of wild-type versus various flfl mutant allelic combinations. flfl795 is a genetically hypomorphic and flflN42 is a null allele. (Df) Df(3R)Exel6170. (D–K) Wild-type and flflN42 L3 larval NBs in metaphase stained for asymmetric machinery components and DNA. Arrow in G points at Pros crescent in wild-type NB, and arrowheads in H–K point at mislocalized components of the Mira complex in flfl-null NBs; the color outlining the arrowhead corresponds to the color of the protein mislocalized.

Homozygous flfl795 animals survive to pharate adults whereas hemizygous flfl795 animals [using Df(3R)Exel6170 to remove one copy of the flfl coding region] (Fig. 1B) only survive until L3. Furthermore, although the cytoplasmic Mira phenotype of flfl795 homozygotes is highly penetrant, the majority of metaphase NBs still display weak Mira crescents, whereas the majority of metaphase NBs of flfl795 hemizygotes display no crescents (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that the strongest EMS allele (flfl795) is nevertheless a hypomorph. We therefore generated a flfl-null allele (flflN42) by imprecise excision of the P-element P{EPgy2}flflEY03585, located ∼1 kb upstream of the flfl translational start site. This allele was confirmed to be a genetic null by the similar expressivities of NB phenotypes in flflN42 homozygotes and flflN42 hemizygotes, as well as in flfl795/flflN42 and flfl795/Df(3R)Exel6170 (Fig. 1C). Consistently, flflN42 NBs are antigen-minus (see below) and molecular analysis indicates that it is a deletion extending into the coding region, deleting the first 1075 base pairs of the coding sequence (Fig. 1B). Subsequent analyses of the phenotype were carried out using the flflN42 allele, hereafter referred to simply as flfl.

In addition to the mislocalization of Mira, the Mira-associated proteins Pros, Brat and Staufen (Stau), are similarly mislocalized to the cytoplasm of metaphase/anaphase flfl NBs (Fig. 1H–K). Pros mislocalization occurs in Asense (Ase)-positive NB lineages (Supplemental Fig. 1A,B) which comprise the majority of lineages in the central brain (Bowman et al. 2008); Ase-negative NBs are Pros-negative in flfl as well as in wild-type brains (data not shown). On the other hand, the localization of members of the other basal complex, Pon and Numb, and of apical complexes is unaffected (Fig. 1H,J,K; data not shown). Hence, during NB division, flfl loss of function specifically affects the localization of the Mira complex.

At interphase and prophase, Mira localizes to both the cytoplasm and cortex of wild-type L3 NBs, with low levels detectable in the nucleus (Fig. 2A). This is in contrast to flfl mutant NBs, which, in addition to the mislocalization of Mira and associated proteins into the cytoplasm during metaphase/anaphase, also display defective protein localization prior to nuclear envelope breakdown. Interphase and prophase flfl NBs display much higher than wild-type levels of nuclear Mira (80% of NBs, n = 80) (Fig. 2A,B; note that most of the volume of a prophase/interphase NB is occupied by its nucleus) and also display ectopic nuclear Pros (71% of NBs, n = 93) (Fig. 2C,D; Supplemental Fig. 1C,D). We ascribe the slightly lower percentage of scored nuclear Pros versus nuclear Mira to the lower detectable levels of the former in larval NBs. Ectopic nuclear Stau or Brat is not detected in flfl NBs, however (data not shown). Therefore, these large cells with ectopic nuclear Pros retain the NB/GMC marker Mira; they also retain other NB/GMC markers such as Deadpan (Dpn) (Supplemental Fig. 1E,F) and Insc (Supplemental Fig. 1G,H), and express Ase, which is found in most central brain NBs. The size and expression profile of these cells suggests that there is Pros mislocalization associated with Ase-positive NBs.

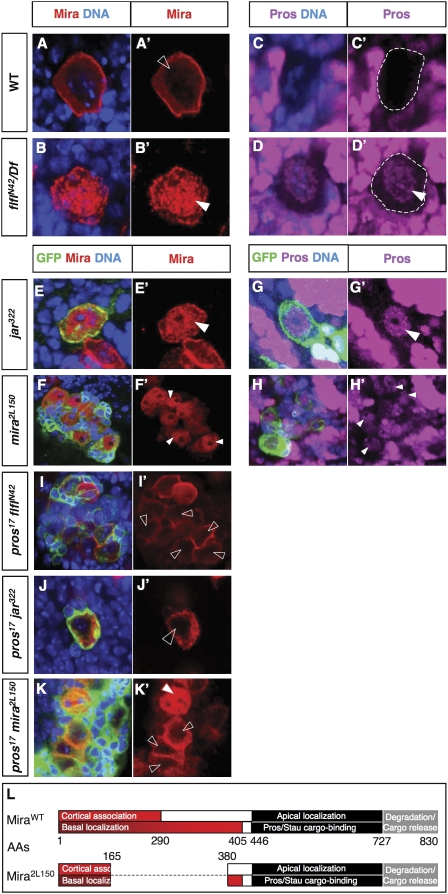

Figure 2.

Failing to tether Mira to the NB cortex results in ectopic nuclear accumulation of Mira and Pros during interphase and prophase. (A–H) Interphase or prophase L3 NBs stained for Mira or Pros. Note: NBs are the largest cells in the clones; in mira2L150 clones there is conversion of GMCs into NB-like cells; hence, the presence of multiple NB-like cells per clone. (A′,B′,E′,F′,I′,J′,K′) Red channel extracted from A, B, E, F, I, J, and K, respectively. (C′,D′,G′,H′) Magenta channel extracted from C, D, G, and H, respectively. (A) Wild-type interphase/prophase NB, where highest levels of Mira are found around the cell cortex, intermediate levels in the cytoplasm and low levels are detected in the nucleus (open arrowhead); the low level of Mira staining detected in the nucleus is not background as it is not found in other cells of the brain. (B) flfl-null interphase/prophase L3 NB, where nuclear Mira (arrowhead) is detected at levels comparable with cortical Mira. (C) Wild-type intephase/prophase L3 NB (outlined by dashed line), where nuclear Pros is undetectable. (D) flfl-null interphase/prophase L3 NB (outlined by dashed line), where nuclear Pros is detected (arrowhead). (E–K) MARCM clones mutant as labeled, in L3 brains; clones are labeled with GFP and brain is further stained for Mira or Pros as well as DNA. (E) jar-null interphase/prophase clone NB, where nuclear Mira (arrowhead) is detected at levels comparable with cortical Mira, unlike in the adjacent NB outside the clone (nongreen). (F) mira mutant (molecular description of which is shown in L) interphase/prophase clone NBs, where nuclear Mira (arrowheads) is detected at levels comparable with cortical Mira. (G) jar-null interphase/prophase clone NB, where nuclear Pros is detected (arrowhead). (H) mira mutant interphase/prophase clone NBs, where nuclear Pros is detected (arrowheads). pros,flfl (I), pros,jar (J), and pros,mira2L150 (K) double-null clones. Unlike flfl, jar, or mira2L150, single-mutant NBs in interphase/prophase, these double-mutant cells have very low levels of nuclear Mira, comparable with wild-type levels (open arrowheads). (K′) The metaphase NB in the pros,mira2L150 clone lacks cortically enriched Mira (red-outlined arrowhead), due to truncation of the cortical association domain in this mira allele. (L) Mira domains as described in Fuerstenberg et al. (1998). The numbering of the amino acid residues (AAs) bordering each domain is indicated below the wild-type or above the mira2L150 allele schematic. The latter is a novel mira allele with an in-frame deletion of amino acid residues 166–379 and retains the C-terminal epitope for the monoclonal anti-Mira antibody.

flfl mutant brains exhibit reduced proliferation

Consistent with ectopic nuclear Pros, flfl NBs exhibit impaired proliferation. Compared with wild type, BrdU incorporation in flfl hemizygous brains is drastically reduced at 96 h after larval hatching (ALH) (Supplemental Fig. 2A–D). Moreover, in comparison with wild-type larvae, which pupate between 96 and 120 h ALH at 25°C and have ∼120 central brain NBs per brain lobe at 96 h ALH, flfl larvae fail to pupate, but can survive for up to 8 d ALH. Even after their extended larval phase, the number of central brain NBs per brain lobe of flfl larvae only reaches ∼80 and analysis of the mushroom body (MB) lineage progeny size reveals a cell-autonomous contribution of flfl toward NB proliferation (Supplemental Fig. 2F). Furthermore, flfl L3 brains have a higher proportion of NBs that are histone-H3 Ser-10 phosphorylated (phospho-H3)-positive compared with wild type (69%, n = 198, in flfl, cf. 26%, n = 227, in wild type), of which the majority of these phospho-H3-positive cells show nuclear enrichment of Mira and Pros (Supplemental Fig. 2G), suggesting the reduced proliferation could result from a block or delay at prophase.

jar loss of function and disruption of the mira cortical/asymmetric localization domain causes protein mislocalization phenotypes similar to those seen in flfl NBs

Similar to the observed flfl phenotypes, disruption of jar has been reported to result in Mira mislocalization to the cytoplasm of dividing embryonic NBs while apical complex proteins remain correctly localized (Petritsch et al. 2003). We generated jar Mosaic Analysis with Mutant-Repressible Cell Marker (MARCM) clones in L3 brains to determine if L3 NBs had the same phenotype as that reported for embryonic NBs. Although metaphase jar322 clone NBs occur with reduced frequency, they do indeed exhibit cytoplasmic Mira but correctly localized Insc, as reported for embryonic NBs. Comparable with flfl larval NBs, inter/prophase jar clone NBs displayed high levels of Mira and Pros in the nuclear region (72%, n = 46 and 62%, n = 58, respectively) (Fig. 2E,G); however, this was not the case for Stau nor Brat (data not shown). We thus conclude that the flfl and jar phenotypes at all phases of the cell cycle are similar, if not identical. The penetrance of these phenotypes is not enhanced in flfl,jar double-mutant NBs (data not shown), suggesting that the two might function in the same pathway (see the Discussion).

A third genotype in which we observed excess nuclear Mira and Pros, was that of a novel allele of mira, mira2L150, also isolated from our clonal screen (100%, n = 70 and 97%, n = 68, respectively) (Fig. 2F,H). mira2L150 consists of an in-frame deletion of amino acid residues 166–379 of the longest isoform (830 amino acids) (Fig. 2L), removing a significant portion of the region previously identified to be required for cortical/basal localization of Mira (Fuerstenberg et al. 1998; Matsuzaki et al. 1998). The mutant Mira2L150 protein retains the C-terminal epitope for the monoclonal anti-Mira antibody and displays cytoplasmic distribution at metaphase/anaphase, even in heterozygous tissue, where presumably half of the protein produced is unable to localize properly.

Nuclear mislocalization of Mira in flfl, jar, or mira2L150 NBs is Pros-dependent

In wild type, the localization of Pros, Stau, and Brat to one side of the NB cortex from prophase to metaphase is Mira-dependent, whereas the asymmetric cortical localization of Mira is unaffected in pros, stau, or brat mutants. Although Mira contains no predicted nuclear localization signals (NLS), its binding partner Pros does (Demidenko et al. 2001). Pros localizes to the nucleus of larval clone NBs mutant for the miraL44-null allele (data not shown), as reported for embryonic NBs (Fuerstenberg et al. 1998). To address whether Pros is required for localizing Mira to the nucleus when cortical localization of Mira is impaired, we examined clones of the three double-mutant genotypes: pros17,flflN42; pros17,jar322, and pros17, mira2L150. In the absence of Pros, Mira is never detected at high levels in the NB nuclei for any of these genotypes (Fig. 2I–K). We therefore conclude that the excess nuclear Mira observed in flflN42, jar322, and mira2L150 NBs is mediated by Pros. These results indicate that when Mira transport and/or cortical association is compromised, Mira and Pros localize to the NB nucleus in a Pros-dependent manner, accumulating to levels far in excess of what is ever observed in wild type. We thus conclude that Pros antagonizes cytoplasmic localization of Mira prior to nuclear envelope breakdown but that this antagonism is overridden by mechanisms tethering Mira to the NB cortex.

Flfl acts in parallel to or downstream from aPKC and Lgl to localize Mira and Pros

To formally examine the epistatic relationships between Flfl and aPKC/Lgl in establishing cortical association of Mira during NB division, we made use of an inducible aPKC RNAi, aPKCRNAi, and a nonphosphorylatable form of lgl, lgl3A (Betschinger et al. 2003). Expression of either construct in wild-type NBs results in Mira mislocalization around the entire cell cortex (Fig. 3A,B,E). Expression of either of these constructs in a flfl background, however, results in a flfl-like phenotype; i.e., cytoplasmic Mira during metaphase/anaphase (Fig. 3C–E), and nuclear Mira at interphase/prophase (data not shown). Therefore, flfl loss of function is formally epistatic to both aPKC loss of function and a constitutively active, nonphosphorylatable form of Lgl, Lgl3A, indicating that Flfl acts either in parallel to or downstream from aPKC and Lgl.

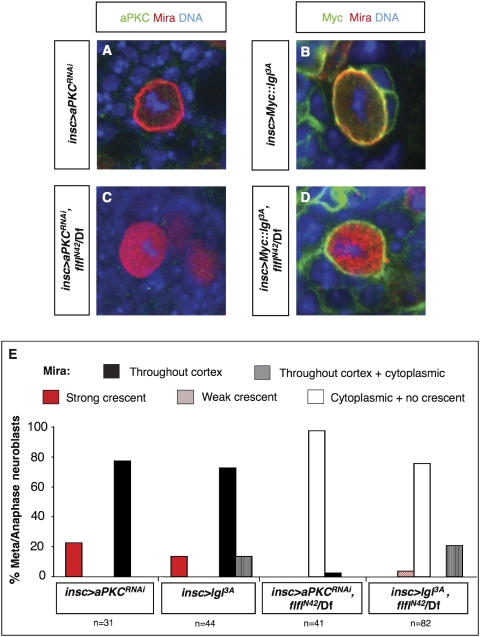

Figure 3.

Flfl acts in parallel to or downstream from Lgl for Mira asymmetric localization. (A) Wild-type L3 brain NB in metaphase expressing aPKCRNAi; reduced (undetectable) aPKC levels results in uniformly cortical Mira. (B) Wild-type L3 brain NB in metaphase expressing Myc-tagged constitutively active Lgl; this form of Lgl is localized around the entire cell cortex, resulting in similar Mira localization. (C) flflN42 hemizygous L3 brain NB in metaphase expressing aPKCRNAi, Mira is cytoplasmic as in flfl NBs. (D) flflN42 hemizygous L3 brain NB in metaphase expressing Myc-tagged constitutively active Lgl; although this form of Lgl is localized around the entire cell cortex, Mira is cytoplasmic as in flfl NBs. (Df) Df(3R)Exel6170. (E) Quantification (percentage) of cortical/cytoplasmic localization of Mira observed in insc > aPKCRNAi; insc > aPKCRNAi, flflN42/Df; insc > Myc∷lgl3A; insc > Myc∷lgl3A, flflN42/Df.

Flfl structure and subcellular localization

Flfl homologs have been identified in several species, from yeast to humans. They all possess the same domain architecture: a Ran-binding domain (RanBD) at the N terminus, similar in three-dimensional structure to the Ena/VASP homology domain 1 (EVH1, which derives its name from the founding members Enabled and Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein) and to the pleckstrin homology domain; followed by a conserved domain of unknown function (DUF625), a region containing armadillo/HEAT repeats (Kittler et al. 2004), and a region of low complexity. Within the DUF625 domain, Flfl contains two putative NLSs (NLS1 and NLS2) as well as a nuclear export signal (NES); close to the C terminus Flfl contains a short conserved stretch of acidic and basic amino acid residues that has been shown to be required for nuclear localization of the Dictyostelium discoideum homolog, SMEK (NLS3) (Fig. 4A; Mendoza et al. 2005). Flfl contains many putative target sites for O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) glycosylation in its C-terminal 300 amino acids and numerous putative phosphorylation sites throughout, some of which are predicted to be PKC targets.

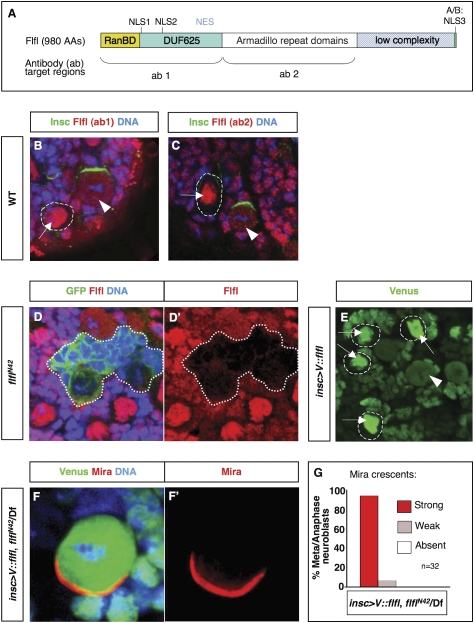

Figure 4.

Flfl structure and subcellular localization. (A) Schematic representation of the structure of Flfl protein and target regions of two antibodies (ab 1 and ab 2) generated against Flfl. The N terminus of Flfl contains a RanBD, followed by a conserved domain of unknown function (DUF625), a region containing armadillo repeat domains and a region of low complexity. Within the DUF625 domain, Flfl contains two NLSs as well as a NES; close to the C terminus, it contains a short stretch of acidic and basic amino acid residues (A/B) that in the Dictystelium discoideum homolog (SMEK) acts as NLS3 (Mendoza et al. 2005). (B,C) The subcellular localization of Flfl is identical, whether detected with ab 1 or ab 2; mainly nuclear in interphase/prophase neurons and NBs (arrows; NBs outlined with dashed lines) and throughout the cell after nuclear envelope breakdown (arrowheads). (D) flflN42 MARCM clone in L3 brain; clone is labeled with GFP and brain is further stained for Flfl and DNA. (D′) Red channel extracted from D. (E) Venus-tagged Flfl driven by NB driver; Venus∷Flfl has same subcellular localization as that observed with anti-Flfl antibodies; nuclear localization in interphase/prophase NBs (arrows; NBs are outlined with dashed lines) and throughout the NB after nuclear envelope breakdown (arrowhead). (F–G) Expression of Venus∷Flfl fully rescues Mira localization in flfl-null NBs. (F′) Red channel extracted from F. (G) Quantification (percentage) of strong, weak, and absent Mira crescents in flflN42 hemizygous NBs rescued by expression of Venus∷Flfl. (Df) Df(3R)Exel6170.

In all cases reported, Flfl homologous proteins are nuclear, with the exception of SMEK, which is indeed nuclear in most cell types but which localizes to the cortex of vegetative cells (Kiger et al. 2003; Kittler et al. 2004; Gingras et al. 2005; Mendoza et al. 2005; Wolff et al. 2006). Remarkably, cortical association of SMEK in vegetative cells is asymmetric, where it is complementary to the cortical domain occupied by Myosin II. The N terminus, which the investigators refer to as an EVH1 domain, is necessary and sufficient for cortical association of SMEK (Mendoza et al. 2005). To observe the localization of Flfl, we generated polyclonal antibodies against two nonoverlapping regions: residues 1–361 (ab1) and residues 362–666 (ab2) of the long isoform. The subcellular localization of Flfl as detected by both antibodies is identical, mainly nuclear in interphase/prophase and throughout the NB after nuclear envelope breakdown (Fig. 4B,C). Flfl is present in all tissues and cell types examined, with the same mitotically directed localization. These antibodies specifically recognize Flfl as seen by the absence of staining in homozygous flfl mutant tissue (Fig. 4D). Flfl is never observed to be cortically enriched, as judged by immunohistochemical detection of endogenous Flfl or expression of Venus-tagged full-length Flfl, V∷Flfl (Fig. 4B,C,E). The V∷Flfl fusion protein not only recapitulates the subcellular localization of endogenous Flfl but is also fully functional. Wild-type localization of Mira is restored when V∷flfl is expressed in a flfl background using the ubiquitous driver da-GAL4 as well as the NB drivers elav-GAL4 (data not shown) or insc-GAL4 (Fig. 4F,G), and moderate levels of V∷flfl rescue the lethality of flfl animals (da-GAL4,flflN42/UAS-V∷flfl,flflN42 raised at 18°C). Higher levels of expression (using da-GAL4 at 25°C or using the stronger ubiquitous drivers act-GAL4 or tub-GAL4) result in lethality, consistent with reported lethality when the Caenorhabditis elegans ortholog SMK-1 was overexpressed (Wolff et al. 2006).

Cytoplasmic or membrane-associated Flfl can mediate asymmetric cortical localization of Mira and its cargo proteins

We showed that Flfl is important for the exclusion of Mira/Pros from the nuclei of interphase/prophase NBs as well as for their asymmetric cortical localization during metaphase/anaphase. To address whether these roles are mediated by nuclear Flfl or whether, at least after nuclear envelope breakdown, they might be regulated by cytoplasmic Flfl we attempted to generate nonnuclear forms of Flfl. Venus fusion proteins in which the last 21 amino acids were deleted, thus removing NLS3 (V∷FlflΔNLS3), or in which all three NLSs were mutated (V∷FlflΔ3NLS) are, surprisingly, not excluded from prophase/interphase NB nuclei (Fig. 5A; data not shown). V∷FlflΔ3NLS can fully rescue the protein localization defects associated with flfl NBs (see Fig. 1C for quantification of the Mira phenotype in flfl meta/anaphase NBs; Fig. 5A,B,G) but, unfortunately, these observations do not allow us to conclude in which subcellular compartment Flfl is required to mediate normal Mira localization. We therefore added extra nuclear export sequences to both the N and C termini of the V∷FlflΔ3NLS fusion protein in a further attempt to exclude it from the NB nucleus. This version of Flfl, V∷FlflΔ3NLS+2NES, was not detectable in NB nuclei, being exclusively observed in the cytoplasm prior to nuclear envelope breakdown (as well as throughout mitosis) (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, although expression of V∷FlflΔ3NLS+2NES can largely restore wild-type localization of Mira during mitosis it is not able to efficiently rescue the excessive nuclear Mira phenotype (58% NBs, n = 115 displayed ectopic nuclear Mira) (Fig. 5C,D).

Figure 5.

Cytoplasmic or membrane-associated Flfl can mediate asymmetric localization of Mira and its cargo proteins. All brains were stained for GFP, Mira and DNA. Interphase/prophase (A) and metaphase (B) flflN42 hemizygous L3 brain NB expressing a Venus-tagged form of Flfl with the first two NLSs mutated and the third truncated. Interphase/prophase (C) and metaphase (D) flflN42 hemizygous L3 brain NBs expressing a Venus-tagged form of Flfl with mutated/truncated NLSs plus two additional NESs on either end. (E) Interphase/prophase and F, metaphase flflN42 hemizygous L3 brain NB expressing a Venus-tagged form of membrane-tethered Flfl. Green channels extracted from A, C, and E are shown in A′, C′, and E′, respectively. Red channels extracted from A–F are shown in A″, B′, C″, D′, E″, and F′, respectively. (Df) Df(3R)Exel6170. (G) Quantifications (percentages) of strong, weak, and absent Mira cresents in flfl hemizygous L3 NBs expressing Venus-tagged flflΔ3NLS, flflΔ3NLS+2NES, flflCAAX. Quantification of the Flfl/Df metaphase phenotype is shown in Figure 1C.

To examine a further possible site of activity of nonnuclear Flfl, we generated a membrane-targeted form of Flfl using the CAAX polyisoprenylation motif, V∷FlflCAAX (Hancock et al. 1989). Expression of this construct results in cortical and nuclear envelope-localized V∷FlflCAAX, with lower levels in the cytoplasm, but no detectable nuclear accumulation (Fig. 5E). Despite a severe disruption to the physiology of cells expressing V∷FlflCAAX (significant blebbing and cell division defects), this fusion protein restored strong cortical crescents of Mira to the same extent as V∷FlflΔ3NLS+2NES in flfl mutant NBs (Fig. 5F,G; see also Fig. 1C). Also consistent with the V∷FlflΔ3NLS+2NES NB observations, V∷FlflCAAX does not efficiently rescue the excessive nuclear Mira phenotype (55% NBs, n = 67, displayed ectopic nuclear Mira) (Fig. 5E).

These results suggest that the roles of Flfl in localizing Mira (hence, Pros) to the cortex and in the nuclear exclusion of Pros (hence, Mira) can be uncoupled, and that they involve cytoplasmic/membrane-associated and nuclear functions of Flfl, respectively. Furthermore, since cytoplasmic/membrane-associated Flfl seems able to asymmetrically localize Mira/Pros, exclusion of Mira/Pros from the nucleus prior to nuclear envelope breakdown does not appear to be a prerequisite for their subsequent asymmetric cortical localization. However, the failure to exclude Pros/Mira from the nucleus may be the cause of the impaired NB proliferation seen in flfl mutants.

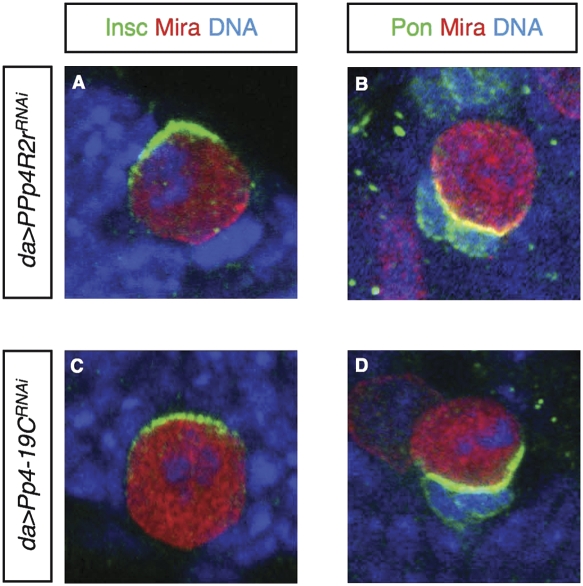

A requirement for other PP4 components in the localization of Mira and its cargo proteins

We wondered whether it was participation of Flfl in the PP4 complex that caused the Mira mislocalization phenotype in NBs. We thus examined Mira localization in NBs with reduced PP4 activity in the presence of Flfl. Expression of either Pp4-19CRNAi or PPP4R2rRNAi results in the same cytoplasmic Mira complex phenotype during metaphase/anaphase as observed in flfl NBs, while components of other asymmetrically localized complexes, such as Insc and PON, are localized correctly (Fig. 6A–D). Similar to flfl mutants, these brains also exhibit a reduction in NB numbers and are smaller than wild-type brains (data not shown). The observation that disruption of any one of the three constituent subunits of the PP4 complex, including the catalytic subunit, causes similar defects in Mira complex localization suggests that there is an essential dephosphorylation step mediated by the PP4 complex, which is required for Mira cortical association.

Figure 6.

Other PP4-containing complex components are required for asymmetric localization of Mira and its cargo proteins in NBs. (A,B) Wild-type L3 brain NB in metaphase/anaphase expressing PPp4R2rRNAi. (C,D) Wild-type L3 brain NB in metaphase/anaphase expressing PP4-19CRNAi. Brains stained for asymmetric machinery components (as labeled) and DNA.

Flfl forms a complex with Mira

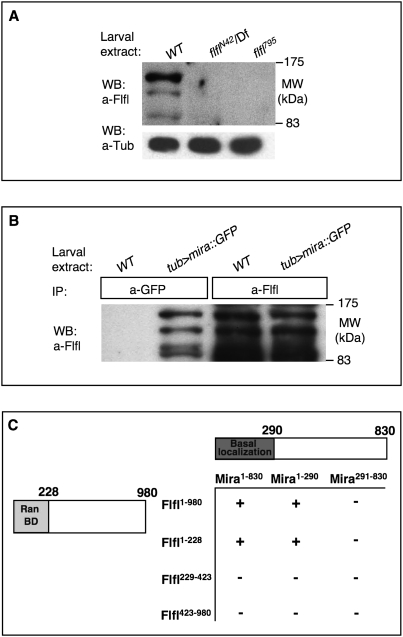

We wondered whether PP4 might be directly targeting the Mira protein complex. Distinct Flfl isoforms are detected by Western analysis on wild-type and not flfl mutant larval extracts (as four bands that migrate at apparent molecular weights roughly between 85 and 160 kDa, the heaviest isoform being the most abundant) (Fig. 7A), which are possibly due to post-translational modifications for which numerous predicted sites exist. The anti-Mira antibodies available to us did not work well on Western analysis, so we overexpressed an Mira∷3GFP fusion protein, which is nondeleterious and capable of recapitulating the subcellular localization of endogenous Mira (Erben et al. 2008). Immunoprecipitation of the Mira fusion protein with an anti-GFP antibody brings down a complex containing Flfl (Fig. 7B). Additionally, yeast two-hybrid assays revealed a direct interaction between Flfl and Mira, mediated by the RanBD domain of Flfl and the cortical association domain of Mira (Fig. 7C). Consistent with the functional importance of this interaction, a Flfl construct that removes the RanBD, FlflΔRanBD, fails to fully rescue the Mira defects seen in flfl NBs (Supplemental Fig. 3). These observations are consistent with the notion that Flfl targets PP4 to Mira and its associated proteins through a direct interaction with Mira.

Figure 7.

Flfl binds Mira. (A) Western blot of wild-type, flfl795, and flflN42 hemizygous L3 tissues, probed with anti-Flfl ab 1. (Df) Df(3R)Exel6170. Flfl protein is detected in the wild-type (WT) lane but not in larvae of either flfl genotype. (B) Flfl forms a complex in vivo with Mira. Immunoprecipitation of either Mira∷GFP fusion protein, with anti-GFP antibody, or of Flfl with anti-Flfl antibody, probed with anti-Flfl antibody. Flfl is detected in the complex pulled down with anti-GFP from Mira∷GFP-expressing larvae but not from wild-type larvae. (C) Full-length Flfl and Mira directly bind each other as assessed by yeast two-hybrid assays. Smaller regions of each protein were tested for binding and the interacting region was narrowed down to the regions Flfl1-228 and Mira1-290. The number of the amino acid residues (AAs) bordering each interacting domain is indicated below next to the schematic of each protein. (+) Growth; (−) no growth on selective media.

Discussion

PP4 is the first phosphatase complex shown to regulate NB asymmetric division

Many components of the machinery involved in establishing NB asymmetry have been identified, but mechanistic insight as to how they exert this important function remains largely elusive. In the case of two kinases, aPKC and Polo, substrates have been found that explain, at least partly, their ability to regulate this process. While a few protein kinases are now known to mediate NB asymmetric divisions, this is the first study demonstrating the requirement for a specific protein phosphatase complex during the process: PP4, a member of the PP2A family of serine-threonine phosphatases. Loss of function or RNAi knockdown of the regulatory subunits flfl/PP4R3 or PPP4R2r/PP4R2 as well as knockdown of the catalytic subunit Pp4C-19C/PP4C of PP4 causes mislocalization of Mira/Pros/Brat/Stau to the cytoplasm of metaphase and anaphase NBs.

PP4 also regulates Mira/Pros localization at interphase and Prophase

Attenuation of PP4 function as described above also causes increased frequency of nuclear Mira/Pros prior to nuclear envelope breakdown. Our observation that depletion of the catalytic subunit of PP4 results in identical phenotypes to the depletion of its regulatory subunits, suggests that phosphatase activity plays a role in the localization of Mira/Pros throughout the NB cell cycle.

Nuclear mislocalization of Mira seen in flfl, jar, or mira2L150 single-mutant NBs requires pros function. This suggests that, when transport of Mira toward or its tethering to the cortex is defective, Pros can take Mira into the nucleus. In this context, the normal relationship between Mira and Pros is reversed, with Pros instructing Mira localization rather than the converse. In the absence of pros, Mira is not localized to the nucleus, even when PP4 function is attenuated. Thus, the role of PP4 on these two temporally distinct localizations of Mira/Pros appears to involve distinct targets since one is a Mira-dependent localization and the other is Pros-dependent.

Flfl can bind Mira and could thus target PP4C to Mira/Pros

In contrast to serine–threonine kinases, substrate specificity for serine/threonine protein phosphatases is thought to be conferred not primarily by sequences adjacent to the target residues but rather by interaction between the substrate and regulatory subunits of the phosphatase complex (Cohen et al. 2005). This is the case for the founding family member PP2A, whose variable subunit composition can also target the complex to distinct subcellular domains (for review, see Sontag 2001) and is thought to be the case also for PP4 (Cohen et al. 2005). We show that Flfl, a regulatory subunit of PP4, is able to bind Mira and that Flfl and Mira are found in a complex in vivo. We were unable to detect binding between Flfl and Pros but since Mira and Pros still colocalize when PP4 function is attenuated, our results also suggest that PP4 function is not required for the Mira–Pros interaction. Therefore, Pros could be recruited to PP4 by its association with Mira, which in turn binds Flfl.

Flfl is nuclear before and cytoplasmic after nuclear envelope breakdown. Our results from nuclear excluded and membrane targeted versions of Flfl suggest that nuclear Flfl is required to exclude Mira/Pros from the nucleus when inefficiently bound to the cytoskeleton/cortex, whereas cytosolic or membrane-associated Flfl is required for the cortical association and asymmetric localization of Mira/Pros/Brat/Stau at metaphase and anaphase. The localization of Mira/Pros prior to and after nuclear envelope breakdown by PP4 may involve different phosphatase substrates. It is tempting to entertain the possibility that Mira dephosphorylation by PP4 in the cytoplasm is required for its asymmetric cortical localization during mitosis, and that Pros dephosphorylation by PP4 in the nucleus is required for its nuclear exclusion/progression through prometaphase. Indeed, a previous study has shown that cortical Pros is highly phosphorylated relative to nuclear Pros (Srinivasan et al. 1998). To test this hypothesis, we attempted to detect enrichment of a lower mobility band of Mira∷3GFP in flfl larval extracts compared with wild type but we were unable to detect this, working at the limits of detectability.

A role for Flfl in mediating F-actin-dependent asymmetric cortical localization of Mira?

Asymmetric cortical localization of proteins during NB asymmetric division is dependent on an intact actin cytoskeleton (Broadus and Doe 1997). Although flfl is required for Mira cortical association, at no point in the NB cell cycle does Flfl exhibit cortical enrichment. However, modified versions of Flfl that are either uniformly cytoplasmic or cortically enriched can both drive asymmetric cortical localization of Mira and its associated proteins. Moreover, the Mira mislocalization phenotypes of flfl are strikingly similar to those of Myo VI/jar. Both mutants exhibit nuclear Mira/Pros prior to and cytoplasmic Mira and associated proteins following NB nuclear envelope breakdown; both Flfl and Jar are cytoplasmic at metaphase/anaphase; and genetically, both Jar and Flfl act parallel to or downstream from Lgl. Further propelled by the presence of a putative actin-binding domain in Flfl (the RanBD domain, which is an EVH1-like domain), we wondered whether Flfl too might facilitate association of Miranda with the actin cytoskeleton either separately from or in association with Jar. However, in vitro assays clearly showed that Flfl does not bind F-actin, although Mira alone did, with comparable strength to that of α-Actinin and Jar, used as controls (Supplemental Fig. 4). Furthermore, we were unable to detect Jar in Flfl containing protein immunoprecipitates. Therefore, it seems unlikely that Flfl acts either directly or in a complex with Jar to facilitate Mira transport along or tethering to the actin cytoskeleton. Still, Flfl could act indirectly; for example, by stabilization of the Mira–Jar association. We speculate that Flfl may act by targeting PP4 to the Mira complex and that the consequent dephosphorylation of a component of this complex facilitates Jar–Mira association.

In Dictyostelium, mutants in the flfl homolog, smkA, exhibit phenotypes similar to strains defective in Myo II assembly (Mendoza et al. 2005), suggesting that smkA may regulate Myo II function. However, in flfl NBs the Mira mislocalization phenotype does not resemble that of Myo II loss of function, which has been described to lead to Mira mislocalization to the mitotic spindle in embryonic NBs (Barros et al. 2003).

Flfl is required for NB proliferation

The reduced proliferation seen in flfl NBs correlates with nuclear localization of Pros/Mira. Nuclear Pros negatively regulates transcription of cell cycle genes and positively regulates differentiation genes, and has been shown to limit NB proliferation (Li and Vaessin 2000; Choksi et al. 2006; Maurange et al. 2008). Therefore, ectopic nuclear Pros is likely to be at least one cause of the NB underproliferation observed in flfl brains. Still, it is possible that flfl has additional functions in promoting proliferation, independent of its role in excluding Pros/Mira from the NB nucleus. Indeed, we detected an excessive proportion of phospho-histone H3-positive flfl NBs relative to wild type. These NBs typically had a nucleus but the cell morphology was not spheroid, as would be expected in prophase cells. This suggests that flfl NBs either have a block or delay in prometaphase or that PP4 may be required for dephosphorylation of Histone H3; in either case, it seems to be required for dephosphorylation of other proteins involved in cell cycle progression. Nonetheless, pros,flfl double-mutant NB clones are indistinguishable from those of pros single mutants, both showing extensive overproliferation, suggesting that the loss of flfl is unable to override the overproliferation induced by loss of pros.

Materials and methods

Drosophila mutants and transgenic lines

Mutant stocks flfl795 and mira2L150 were identified from a mosaic analysis with a MARCM screen of EMS mutagenized FRT82B males (fed with 26 mM EMS in 1% [w/v] aqueous solution of sucrose for 18 h) (W.G. Somers, W. Chia., R. Sousa-Nunes, unpubl.). The flflN42 allele was generated by standard genetic protocol, mobilizing the P-element EPgy2flflEY03585 (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center). Break points of the imprecise excisions were determined by genomic PCR using primer pairs that spanned the flfl locus.

The following fly stocks were also used in this study: tubP-GAL4, Df(3R)Exel6170 and da-GAL4 (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center); elav-GAL4,hs-FLP;UAS-nLacZ,UAS-mCD8∷GFP;P{FRT}82B,tubP-GAL80) (Bello et al. 2003); jar322 (Petritsch et al. 2003); pros17 (Doe et al. 1991; Vaessin et al. 1991); aurA8839 (Lee et al. 2006a; Wang et al. 2006); Insc-GAL4: P{GAL4}MZ1407 (a gift from J. Urban); UAS-lgl3A∷Myc (Betschinger et al. 2003); UAS-mira∷3GFP (C. Petritsch, unpubl.). UAS-aPKCRNAi, UAS-PPP4R2rRNAi, and UAS-PP4-19CRNAi (Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center, VDRC) (Dietzl et al. 2007). The yw stock was used as wild-type control. Transgenic flies, UAS-V∷flfl, UAS-V∷FlflRanD, UAS-V∷FlflΔRanD, UAS-V∷flflΔNLS3, UAS-V∷flflΔ3NLS, UAS-V∷flflΔ3NLS+2NES, and UAS-V∷flflCAAX, were generated using standard methods (see below) and constructs were injected by BestGene, Inc.

Generation of positively labeled clones

GFP-labeled clones were generated according to the MARCM technique reported previously (Lee and Luo 1999). The 3R MARCM driver was crossed to mutant stocks carrying FRT82B (day 0) and females left to lay for 24 h at 25°C. Lay tubes were heat-shocked for 1.5 h at 37°C on both days 2 and 3. Wandering L3 of the desired genotype (elav-GAL4,hs-FLP/+;UAS-nLacZ,UAS-mCD8∷GFP/+;P{FRT}82B,tubP-GAL80/P{FRT}82B,mutation) were collected on days 6 and 7, their brains dissected and processed for immunohistochemistry. Clone NBs can be identified by molecular markers and distinguished from GMCs (with whom they share these markers) by size, being the largest cell in a clone, typically ∼12-μm diameter.

Immunohistochemistry and imaging

For immunohistochemistry, brains were fixed for 15 min in 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS. The following antibodies were used: rat anti-Flfl (generated in this study; see below), 1/1000; mouse and rabbit anti-GFP (Invitrogen); mouse anti-Mira (Ohshiro et al. 2000), 1/50; mouse anti-Pros (Spana and Doe 1995) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), 1/10; preadsorbed rabbit anti-Stau (St Johnston et al. 1991), 1/2000; rabbit anti-Brat (Sonoda and Wharton 2001; Betschinger et al. 2006), 1/200; preadsorbed rabbit anti-Numb (Uemura et al. 1989), 1/1000; rabbit anti-Pon (Lu et al. 1998), 1/500; guinea-pig anti-Gαi (Yu et al. 2005), 1/250; rabbit anti-aPKCζ C20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), 1/1000; mouse monoclonal anti-Jar 3C7 (Kellerman and Miller 1992), 1/5; preadsorbed rabbit anti-Insc (Kraut and Campos-Ortega 1996), 1/1000; rabbit anti-Pins (Yu et al. 2000), 1/1000; rabbit anti-Baz/Par-3 (Kuchinke et al. 1998) 1/1000; rabbit anti-Par-6 (Petronczki and Knoblich 2001), 1/1000; guinea-pig anti-Dpn (a gift from J. Skeath), 1/500; mouse anti-BrdU (Roche Applied Science), 1/20. Secondary antibodies were conjugated to either Alexa-Fluor-488 or Alex-Fluor-555 (Molecular Probes) and used at 1/500. DNA stain was TO-PRO3 iodide (Molecular Probes). Brains were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) and images were obtained using either a Zeiss LSM 510 or a Leica SP5 confocal microscope.

Constructs

For cloning purposes, PCR fragments were generated from available cDNAs. PCR fragments were cloned into the following vectors: pACT2 and pAS2-1 (Invitrogen) for yeast 2-hybrid assays; pGEX-5X (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) for protein expression, and the Gateway Destination vector pTVW (Invitrogen) for the generation of transgenic flies.

Site-directed mutagenesis

UAS-V∷flflΔ3NLS was created by sequential site-directed mutagenesis of NLSI and NLSII of wild-type flfl using the QuickChange kit (Stratagene), after truncation of NLS3. Mutant primers were used to change the arginine and lysine residues within the predicted NLSs (NLSI: R159, K160, and K162; NLS2: K237, K238, and R240) into alanines. UAS-V∷flflΔ3NLS+2NES, was created by adding sequences corresponding to the NES of the Protein Kinase A inhibitor, LALKLAGLDI (Wen et al. 1995) to both termini of UAS-V∷flflΔ3NLS. UAS-V∷flflCAAX was generated by designing a 3′ PCR primer with a sequence coding the K-Ras prenylation motif KDGKKKKKKSKTKCVIM (Hancock et al. 1989).

Scoring of excess nuclear Mira and ectopic nuclear Pros

Mira levels in wild-type interphase NBs are variable, very low just after a division and presumably building up toward the following division. Nonetheless, in wild-type interphase/prophase NBs nuclear Mira is always detected at considerably lower levels than cortical Mira. Therefore, excess nuclear Mira in mutant NBs was scored as detection of nuclear levels comparable with those observed in the cortex of the same cell (whether they be high or low) rather than scored as detection above a certain threshold level. Pros was always undetectable in wild-type NB nuclei. Thus, although Pros levels in mutant NBs were variable, as long as nuclear Pros was detectable NBs were scored as containing ectopic nuclear Pros.

Biochemistry

Recombinant polypeptides corresponding to Flfl amino acid residues 1–361 and 362–666 were expressed separately in Escherichia coli using the pGEX-5X plasmid. Polyacrylamide gel slices containing the induced polypeptides, were excised, crushed, and used to immunize rats according to standard protocols.

For immunoprecipitation experiments, L3 brains were lysed in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% NP40 containing Protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), 1 tablet per 50 mL. Extracts were processed by SDS-PAGE or immunoprecipitated using rabbit anti-GFP (Sigma) or Rat anti-Flfl (this study); immunocomplexes were bound to Protein G Sepharose (GE Healthcare) before SDS-PAGE. Gels were blotted onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore), probed with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Dako and Vecta Laboratories), and developed using the SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate kit (Pierce).

Yeast 2-Hybrid assays were performed using standard protocols. Coding sequences corresponding to Flfl products (amino acid residues 1–980, 1–228, 229–423, and 423–980 of the long isoform) were cloned into pACS2-1; and Mira products (amino acid residues 1–830, 1–290, and 291–830) were cloned into pACT2. An interaction between Flfl and Mira was determined by the ability to activate the histidine reporter in Y190 yeast.

BrdU labeling

Proliferating cells within whole brains were detected as described previously (Ceron et al. 2001). Dissected larval tissue was given a 40-min pulse of 37.5 μg/mL BrdU in Shields and Sang 3M insect medium. Tissue was then fixed for 15 min in 3.7% formaldehyde, and DNA denatured with 2 N HCl for 40 min, before washing in PBS and incubating with anti-BrdU. Secondary detection was performed as for other immunohistochemical assays.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cathy Slack, Paul Overton, Cedric Maurange, Louise Cheng, Julia Pendred, Patricia Cohen, Bruno Bello, Alex Gould, Yuh-Nung Jan, Chris Doe, Andreas Wodarz, Fumio Matsuzaki, Jurgen Knoblich, Claudia Petritsch, Daniel St-Johnston, Robin Wharton, Cahir O'Kane, Liqun Luo, Exelixis, and the Bloomington, Szeged, and VDRC stock centers for advice, flies, and reagents; we thank Harpreet Sidhu, Serene Gwee, Krystle Tan, and Simone Lackner for technical assistance. We are grateful to Claudia Petritsch for providing reagents prior to publication. R.S.-N. thanks Alex Gould for hosting and supporting her during the final stages of this work. This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council, Singapore Millennium Foundation, Wellcome Trust Travelling Research Fellowship (070152) (W.G.S.), and the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (R.S.-N.). This work was initiated at the MRC Centre for Developmental Neurobiology, King’s College, London.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1723609.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

References

- Barros C.S., Phelps C.B., Brand A.H. Drosophila nonmuscle myosin II promotes the asymmetric segregation of cell fate determinants by cortical exclusion rather than active transport. Dev. Cell. 2003;5:829–840. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00359-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello B.C., Hirth F., Gould A.P. A pulse of the Drosophila Hox protein Abdominal-A schedules the end of neural proliferation via neuroblast apoptosis. Neuron. 2003;37:209–219. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello B., Reichert H., Hirth F. The brain tumor gene negatively regulates neural progenitor cell proliferation in the larval central brain of Drosophila. Development. 2006;133:2639–2648. doi: 10.1242/dev.02429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betschinger J., Mechtler K., Knoblich J.A. The Par complex directs asymmetric cell division by phosphorylating the cytoskeletal protein Lgl. Nature. 2003;422:326–330. doi: 10.1038/nature01486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betschinger J., Eisenhaber F., Knoblich J.A. Phosphorylation-induced autoinhibition regulates the cytoskeletal protein Lethal (2) giant larvae. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:276–282. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betschinger J., Mechtler K., Knoblich J.A. Asymmetric segregation of the tumor suppressor brat regulates self-renewal in Drosophila neural stem cells. Cell. 2006;124:1241–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman S.K., Rolland V., Betschinger J., Kinsey K.A., Emery G., Knoblich J.A. The tumor suppressors Brat and Numb regulate transit-amplifying neuroblast lineages in Drosophila. Dev. Cell. 2008;14:535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadus J., Doe C.Q. Extrinsic cues, intrinsic cues and microfilaments regulate asymmetric protein localization in Drosophila neuroblasts. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:827–835. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceron J., Gonzalez C., Tejedor F.J. Patterns of cell division and expression of asymmetric cell fate determinants in postembryonic neuroblast lineages of Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 2001;230:125–138. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choksi S.P., Southall T.D., Bossing T., Edoff K., de Wit E., Fischer B.E., van Steensel B., Micklem G., Brand A.H. Prospero acts as a binary switch between self-renewal and differentiation in Drosophila neural stem cells. Dev. Cell. 2006;11:775–789. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P. The structure and regulation of protein phosphatases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1989;58:453–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P.T., Philp A., Vazquez-Martin C. Protein phosphatase 4—From obscurity to vital functions. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3278–3286. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidenko Z., Badenhorst P., Jones T., Bi X., Mortin M.A. Regulated nuclear export of the homeodomain transcription factor Prospero. Development. 2001;128:1359–1367. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzl G., Chen D., Schnorrer F., Su K.C., Barinova Y., Fellner M., Gasser B., Kinsey K., Oppel S., Scheiblauer S., et al. A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;448:151–156. doi: 10.1038/nature05954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doe C.Q., Chu-LaGraff Q., Wright D.M., Scott M.P. The prospero gene specifies cell fates in the Drosophila central nervous system. Cell. 1991;65:451–464. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90463-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger B., Chell J.M., Brand A.H. Insights into neural stem cell biology from flies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2008;363:39–56. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erben V., Waldhuber M., Langer D., Fetka I., Jansen R.P., Petritsch C. Asymmetric localization of the adaptor protein Miranda in neuroblasts is achieved by diffusion and sequential interaction of Myosin II and VI. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:1403–1414. doi: 10.1242/jcs.020024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuerstenberg S., Peng C.Y., Alvarez-Ortiz P., Hor T., Doe C.Q. Identification of Miranda protein domains regulating asymmetric cortical localization, cargo binding, and cortical release. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 1998;12:325–339. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1998.0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras A.C., Caballero M., Zarske M., Sanchez A., Hazbun T.R., Fields S., Sonenberg N., Hafen E., Raught B., Aebersold R. A novel, evolutionarily conserved protein phosphatase complex involved in cisplatin sensitivity. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2005;4:1725–1740. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500231-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock J.F., Magee A.I., Childs J.E., Marshall C.J. All ras proteins are polyisoprenylated but only some are palmitoylated. Cell. 1989;57:1167–1177. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helps N.R., Brewis N.D., Lineruth K., Davis T., Kaiser K., Cohen P.T. Protein phosphatase 4 is an essential enzyme required for organisation of microtubules at centrosomes in Drosophila embryos. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:1331–1340. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.10.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeshima-Kataoka H., Skeath J.B., Nabeshima Y., Doe C.Q., Matsuzaki F. Miranda directs Prospero to a daughter cell during Drosophila asymmetric divisions. Nature. 1997;390:625–629. doi: 10.1038/37641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerman K.A., Miller K.G. An unconventional myosin heavy chain gene from Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Biol. 1992;119:823–834. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiger A.A., Baum B., Jones S., Jones M.R., Coulson A., Echeverri C., Perrimon N. A functional genomic analysis of cell morphology using RNA interference. J. Biol. 2003;2:27. doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-2-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittler R., Putz G., Pelletier L., Poser I., Heninger A.K., Drechsel D., Fischer S., Konstantinova I., Habermann B., Grabner H., et al. An endoribonuclease-prepared siRNA screen in human cells identifies genes essential for cell division. Nature. 2004;432:1036–1040. doi: 10.1038/nature03159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblich J.A. Mechanisms of asymmetric stem cell division. Cell. 2008;132:583–597. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut R., Campos-Ortega J.A. inscuteable, a neural precursor gene of Drosophila, encodes a candidate for a cytoskeleton adaptor protein. Dev. Biol. 1996;174:65–81. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut R., Chia W., Jan L.Y., Jan Y.N., Knoblich J.A. Role of inscuteable in orienting asymmetric cell divisions in Drosophila. Nature. 1996;383:50–55. doi: 10.1038/383050a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchinke U., Grawe F., Knust E. Control of spindle orientation in Drosophila by the Par-3-related PDZ-domain protein Bazooka. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:1357–1365. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)00016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T., Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.Y., Andersen R.O., Cabernard C., Manning L., Tran K.D., Lanskey M.J., Bashirullah A., Doe C.Q. Drosophila Aurora-A kinase inhibits neuroblast self-renewal by regulating aPKC/Numb cortical polarity and spindle orientation. Genes & Dev. 2006a;20:3464–3474. doi: 10.1101/gad.1489406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.Y., Wilkinson B.D., Siegrist S.E., Wharton R.P., Doe C.Q. Brat is a Miranda cargo protein that promotes neuronal differentiation and inhibits neuroblast self-renewal. Dev. Cell. 2006b;10:441–449. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Vaessin H. Pan-neural Prospero terminates cell proliferation during Drosophila neurogenesis. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:147–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B., Rothenberg M., Jan L.Y., Jan Y.N. Partner of Numb colocalizes with Numb during mitosis and directs Numb asymmetric localization in Drosophila neural and muscle progenitors. Cell. 1998;95:225–235. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki F., Ohshiro T., Ikeshima-Kataoka H., Izumi H. miranda localizes staufen and prospero asymmetrically in mitotic neuroblasts and epithelial cells in early Drosophila embryogenesis. Development. 1998;125:4089–4098. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.20.4089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurange C., Cheng L., Gould A.P. Temporal transcription factors and their targets schedule the end of neural proliferation in Drosophila. Cell. 2008;133:891–902. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza M.C., Du F., Iranfar N., Tang N., Ma H., Loomis W.F., Firtel R.A. Loss of SMEK, a novel, conserved protein, suppresses MEK1 null cell polarity, chemotaxis, and gene expression defects. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:7839–7853. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.17.7839-7853.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihindukulasuriya K.A., Zhou G., Qin J., Tan T.H. Protein phosphatase 4 interacts with and down-regulates insulin receptor substrate 4 following tumor necrosis factor-α stimulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:46588–46594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408067200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourtada-Maarabouni M., Kirkham L., Jenkins B., Rayner J., Gonda T.J., Starr R., Trayner I., Farzaneh F., Williams G.T. Functional expression cloning reveals proapoptotic role for protein phosphatase 4. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:1016–1024. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohshiro T., Yagami T., Zhang C., Matsuzaki F. Role of cortical tumour-suppressor proteins in asymmetric division of Drosophila neuroblast. Nature. 2000;408:593–596. doi: 10.1038/35046087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier M.L., Woods D., Greig S., Phan P.G., Radovic A., Bryant P., O'Kane C.J. Rapsynoid/partner of inscuteable controls asymmetric division of larval neuroblasts in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:RC84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-j0003.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng C.Y., Manning L., Albertson R., Doe C.Q. The tumour-suppressor genes lgl and dlg regulate basal protein targeting in Drosophila neuroblasts. Nature. 2000;408:596–600. doi: 10.1038/35046094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petritsch C., Tavosanis G., Turck C.W., Jan L.Y., Jan Y.N. The Drosophila myosin VI Jaguar is required for basal protein targeting and correct spindle orientation in mitotic neuroblasts. Dev. Cell. 2003;4:273–281. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronczki M., Knoblich J.A. DmPAR-6 directs epithelial polarity and asymmetric cell division of neuroblasts in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:43–49. doi: 10.1038/35050550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhyu M.S., Jan L.Y., Jan Y.N. Asymmetric distribution of numb protein during division of the sensory organ precursor cell confers distinct fates to daughter cells. Cell. 1994;76:477–491. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson A.V., Carr C.E., Ruvkun G. Gene activities that mediate increased life span of C. elegans insulin-like signaling mutants. Genes & Dev. 2007;21:2976–2994. doi: 10.1101/gad.1588907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M., Shevchenko A., Shevchenko A., Knoblich J.A. A protein complex containing Inscuteable and the Gα-binding protein Pins orients asymmetric cell divisions in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:353–362. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M., Petronczki M., Dorner D., Forte M., Knoblich J.A. Heterotrimeric G proteins direct two modes of asymmetric cell division in the Drosophila nervous system. Cell. 2001;107:183–194. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00521-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober M., Schaefer M., Knoblich J.A. Bazooka recruits Inscuteable to orient asymmetric cell divisions in Drosophila neuroblasts. Nature. 1999;402:548–551. doi: 10.1038/990135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuldt A.J., Adams J.H., Davidson C.M., Micklem D.R., Haseloff J., St Johnston D., Brand A.H. Miranda mediates asymmetric protein and RNA localization in the developing nervous system. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:1847–1857. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen C.P., Jan L.Y., Jan Y.N. Miranda is required for the asymmetric localization of Prospero during mitosis in Drosophila. Cell. 1997;90:449–458. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80505-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack C., Somers W.G., Sousa-Nunes R., Chia W., Overton P.M. A mosaic genetic screen for novel mutations affecting Drosophila neuroblast divisions. BMC Genet. 2006;7:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.A., Lau K.M., Rahmani Z., Dho S.E., Brothers G., She Y.M., Berry D.M., Bonneil E., Thibault P., Schweisguth F., et al. aPKC-mediated phosphorylation regulates asymmetric membrane localization of the cell fate determinant Numb. EMBO J. 2007;26:468–480. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda J., Wharton R.P. Drosophila Brain Tumor is a translational repressor. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:762–773. doi: 10.1101/gad.870801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontag E. Protein phosphatase 2A: The Trojan Horse of cellular signaling. Cell. Signal. 2001;13:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(00)00123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spana E.P., Doe C.Q. The prospero transcription factor is asymmetrically localized to the cell cortex during neuroblast mitosis in Drosophila. Development. 1995;121:3187–3195. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.10.3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S., Peng C.Y., Nair S., Skeath J.B., Spana E.P., Doe C.Q. Biochemical analysis of ++Prospero protein during asymmetric cell division: Cortical Prospero is highly phosphorylated relative to nuclear Prospero. Dev. Biol. 1998;204:478–487. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Johnston D., Beuchle D., Nusslein-Volhard C. Staufen, a gene required to localize maternal RNAs in the Drosophila egg. Cell. 1991;66:51–63. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90138-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumiyoshi E., Sugimoto A., Yamamoto M. Protein phosphatase 4 is required for centrosome maturation in mitosis and sperm meiosis in C. elegans. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:1403–1410. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.7.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tio M., Udolph G., Yang X., Chia W. cdc2 links the Drosophila cell cycle and asymmetric division machineries. Nature. 2001;409:1063–1067. doi: 10.1038/35059124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura T., Shepherd S., Ackerman L., Jan L.Y., Jan Y.N. numb, a gene required in determination of cell fate during sensory organ formation in Drosophila embryos. Cell. 1989;58:349–360. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90849-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaessin H., Grell E., Wolff E., Bier E., Jan L.Y., Jan Y.N. prospero is expressed in neuronal precursors and encodes a nuclear protein that is involved in the control of axonal outgrowth in Drosophila. Cell. 1991;67:941–953. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Somers G.W., Bashirullah A., Heberlein U., Yu F., Chia W. Aurora-A acts as a tumor suppressor and regulates self-renewal of Drosophila neuroblasts. Genes & Dev. 2006;20:3453–3463. doi: 10.1101/gad.1487506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Ouyang Y., Somers W.G., Chia W., Lu B. Polo inhibits progenitor self-renewal and regulates Numb asymmetry by phosphorylating Pon. Nature. 2007;449:96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature06056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen W., Meinkoth J.L., Tsien R.Y., Taylor S.S. Identification of a signal for rapid export of proteins from the nucleus. Cell. 1995;82:463–473. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90435-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz-Peitz F., Knoblich J.A. Lethal giant larvae take on a life of their own. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodarz A., Ramrath A., Kuchinke U., Knust E. Bazooka provides an apical cue for Inscuteable localization in Drosophila neuroblasts. Nature. 1999;402:544–547. doi: 10.1038/990128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodarz A., Ramrath A., Grimm A., Knust E. Drosophila atypical protein kinase C associates with Bazooka and controls polarity of epithelia and neuroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:1361–1374. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff S., Ma H., Burch D., Maciel G.A., Hunter T., Dillin A. SMK-1, an essential regulator of DAF-16-mediated longevity. Cell. 2006;124:1039–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh P.Y., Yeh K.H., Chuang S.E., Song Y.C., Cheng A.L. Suppression of MEK/ERK signaling pathway enhances cisplatin-induced NF-κB activation by protein phosphatase 4-mediated NF-κB p65 Thr dephosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:26143–26148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F., Morin X., Cai Y., Yang X., Chia W. Analysis of partner of inscuteable, a novel player of Drosophila asymmetric divisions, reveals two distinct steps in inscuteable apical localization. Cell. 2000;100:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80676-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F., Cai Y., Kaushik R., Yang X., Chia W. Distinct roles of Gαi and Gβ13F subunits of the heterotrimeric G protein complex in the mediation of Drosophila neuroblast asymmetric divisions. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:623–633. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F., Wang H., Qian H., Kaushik R., Bownes M., Yang X., Chia W. Locomotion defects, together with Pins, regulates heterotrimeric G-protein signaling during Drosophila neuroblast asymmetric divisions. Genes & Dev. 2005;19:1341–1353. doi: 10.1101/gad.1295505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Ozawa Y., Lee H., Wen Y.D., Tan T.H., Wadzinski B.E., Seto E. Histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) activity is regulated by interaction with protein serine/threonine phosphatase 4. Genes & Dev. 2005;19:827–839. doi: 10.1101/gad.1286005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G., Boomer J.S., Tan T.H. Protein phosphatase 4 is a positive regulator of hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:49551–49561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]