Abstract

Bioactive food components containing n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) modulate multiple determinants which link inflammation to cancer initiation and progression. Therefore, in this study, fat-1 transgenic mice which convert endogenous n-6 PUFA to n-3 PUFA in multiple tissues, were injected with azoxymethane followed by 3 cycles of dextran sodium sulphate (DSS) to induce colitis-associated cancer. fat-1 mice exhibited a reduced number of colonic adenocarcinomas per mouse (1.05±0.29 vs 2.12±0.51, p=0.033), elevated apoptosis (p=0.03) and a decrease in n-6 PUFA-derived eicosanoids, compared to wild type (wt) mice. To determine whether the chemoprotective effects of n-3 PUFA could be attributed to its pleiotropic anti-inflammatory properties, colonic inflammation and injury scores were evaluated 5 d after DSS exposure followed by either a 3 d or 2 wk recovery period. There was no effect of n-3 PUFA at 3 d. However, following a 2 wk recovery period, colonic inflammation and ulceration scores returned to pretreatment levels compared to 3 d recovery only in fat-1 mice. For the purpose of examining the specific reactivity of lymphoid elements in the intestine, CD3+ T cells, CD4+ T helper cells and macrophages from colonic lamina propria were quantified. Comparison of 3 d vs 2 wk recovery time points revealed that fat-1 mice exhibited decreased (p<0.05) CD3+, CD4+ T helper, and macrophage cell numbers per colon as compared to wt mice. These results suggest that the anti-tumorigenic effect of n-3 PUFA may be mediated in part via its anti-inflammatory properties.

Keywords: inflammation, chemoprevention, dextran sodium sulphate, tumor promotion

Introduction

Human inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are chronic, relapsing inflammatory conditions of unknown etiology. Genetic, immunological, and environmental factors have been implicated (1, 2). These diseases are characterized by two overlapping clinical phenotypes, i.e., ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). UC primarily involves the colon with inflammation restricted to the mucosa. The inflammation in CD often involves the small intestine along with the colon and other organs (3). CD affects more than 500,000 individuals in the U.S. and represents the second most common chronic inflammatory disorder after rheumatoid arthritis. In addition, the risk of developing colorectal cancer increases ~0.5–1% each year after 7 years in patients with chronic intestinal inflammation (2, 4). However, despite compelling data indicating a functional link between inflammation and colon cancer, the pathways regulating initiation and maintenance of inflammation during cancer development remain poorly understood. Therefore, it is important to identify overlapping regulatory relationships among genes considered to drive inflammation-associated colonic tumor development. To date, the effects of n-3 PUFA on susceptibility to colitis and colon cancer has not been determined.

Colorectal cancer continues to pose a serious health problem in the United States. Over a lifetime, a person has a 1 in 18 chance of developing invasive colorectal cancer (5). From a dietary perspective, a growing number of published reports support the contention that bioactive food components containing n-3 PUFA modulate important determinants which link inflammation to cancer development and progression (6–10). In addition, clinical and experimental data indicate a protective effect of n-3 PUFA on colon cancer (11–15). Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; 20:5Δ5,8,11,14,17) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6Δ4,7,10,13,16,19) are typical n-3 PUFA (found in fish oil), defined according to the position of the first double bond from the methyl end of the molecule which is designated “n-3”. In contrast, dietary lipids rich in n-6 PUFA (found in vegetable oils), e.g., linoleic acid (18:2Δ9,12) and arachidonic acid (20:4Δ5,8,11,14), enhance the development of colon tumors (14, 16). These effects are exerted at both the initiation and post-initiation stages of carcinogenesis (11, 14, 17). Consistent with human clinical trials (12, 13, 15, 18), we have shown that the balance between colonic epithelial cell proliferation and apoptosis can be favorably modulated by dietary n-3 PUFA, conferring resistance to toxic carcinogenic agents (8, 14). This is significant because the typical Western diet contains 10 to 20 times more n-6 than n-3 PUFA (19). Unfortunately, to date, a unifying mechanistic hypothesis addressing how n-3 PUFA selectively suppress colon cancer compared to n-6 PUFA is lacking. Since mammals cannot produce n-3 PUFA from the major n-6 PUFA found in the diet due to the lack of Δ15-desaturase activity, it is necessary to enrich the diet with EPA and/or DHA in order to assess their biological properties in vivo. Recently, a fat-1 gene encoding an n-3 fatty acid desaturase has been cloned from C. elegans and expressed in mammalian cells (20). This enzyme can catalyze the conversion of n-6 PUFA to n-3 PUFA by introducing a double bond into fatty acyl chains. The generation of transgenic mice expressing fat-1 will now allow us for the first time to investigate the biological properties of n-3 PUFA without having to incorporate DHA in the diet (21).

The dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) method of induced inflammation is an excellent preclinical model of colitis that exhibits many phenotypic characteristics relevant to the human disease (22, 23). When combined with azoxymethane, (AOM), at least 50% of the animals (C57BL/6 mice) develop colonic adenocarcinomas (24, 25). Macroscopically, a dysplasia-invasive adenocarcinoma sequence is observed, resulting in both flat and polypoid tumors. This is analogous to the dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM) seen in patients with ulcerative colitis (4). Therefore, in this study we exposed fat-1 mice to AOM followed by 3 rounds of DSS in order to test the hypothesis that the endogenous production of n-3 PUFA affords protection against colitis-associated colon carcinogenesis. Specifically, we determined how n-3 PUFA and chronic inflammation influence colonic: (i) tumor formation, (ii) inflammation and injury scores, (iii) specific activity of lymphoid elements and (iv) eicosanoid production.

Methods

Animals

Fat-1 transgenic mice were generated and backcrossed onto a C57BL/6 background as previously described (21). All procedures followed the guidelines approved by PHS and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Texas A&M University. The colony of fat-1 mice used for this study was generated by breeding heterozygous mice. The genotype and phenotype of offspring of each animal were characterized using isolated DNA and total lipids from mice tails (Supplemental Table 1). Specific pathogen-free animals were maintained under barrier conditions and fed a 10% safflower oil diet (Research Diets) ad libitum with a 12 h light/dark cycle. The diet contained 40 (g/100 g diet) sucrose, 20 casein, 15 corn starch, 0.3 DL-methionine, 3.5 AIN 76A salt mix, 1.0 AIN 76A mineral mix, 0.2 choline chloride, 5 fiber (cellulose), 10 safflower oil.

Colon tumor induction

fat-1 and litter-mate wt (control) mice (10–20 wks old) were injected intraperitoneally with 12.5 mg/kg body weight AOM (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by 3 rounds of DSS treatment. After 1 wk, 2.5% DSS (molecular weight, 36,000 to 50,000; MP Biomedicals) was administered in the drinking water for 5 d, followed by 16 d of tap water. This cycle was repeated twice (5 d of 2.5% DSS followed by a 16 d recovery period and 4 d of 2% DSS), and mice were terminated 12 wk after completion of the final DSS cycle. Subsequently, each colon was resected proximally at the junction between the cecum and distally at the anus, flushed with PBS, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (14). Tumors were sectioned and dysplasia, adenomas and carcinomas were charted and evaluated by a board-certified pathologist in a blinded manner as we have previously described (14, 26).

In situ apoptosis measurement

Apoptosis was measured in paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end (Oncor) labeling (TUNEL) method (17, 27).

Colitis induction and histological scoring

fat-1 and wt mice (8–14 wks) were provided 2.5% DSS in the drinking water for 5 d, after which animals were provided with water only and allowed to recover for either 3 d or 2 wks prior to sacrifice. At each necropsy interval, the entire colon was removed, measured, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and paraffin embedded. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Histological examination was performed in a blinded manner by a board-certified pathologist, and the degree of inflammation (score, 0–3) and epithelial injury (score, 0–3) on microscopic cross-sections of the colon was graded. The presence of occasional inflammatory cells in the lamina propria was assigned a value of 0; increased numbers of inflammatory cells in the lamina propria as 1; confluence of inflammatory cells, extending into submucosa, as 2; and transmural extension of the infiltrate as 3. For epithelium injury, no mucosal damage was scored as 0; discrete lympho-epithelial lesions were scored as 1; surface mucosal erosion or focal ulceration was scored as 2; and extensive mucosal damage and extension into deeper structures of the bowel wall was scored as 3.

Isolation of colonic lamina propria lymphocytes

Lamina propria lymphocytes were isolated from mouse colon as previously described with some modification (28, 29). Briefly, the colon was flushed clean and incubated in media containing Ca2+, Mg2+ free HBSS (Sigma-Aldrich), 5 mM DTT and 30 mM Na4EDTA at 37 °C, 100 rpm for 15 min. Subsequently, colons were placed on ice and gently scraped using a rubber policeman to remove the intact crypts. Following a washing step in Ca2+, Mg2+ free HBSS, the remaining tissue was cut into small pieces, and incubated in Ca2+, Mg2+ free HBSS containing 1 mg/mL type II and type IV collagenase (Worthington) at 37 °C, 100 rpm for 40 min. The liberated lamina propria cells were freely passed through a stainless steel grid (60-mesh) and further purified by density gradient centrifugation in 40–70 % Percoll (Amersham) in PBS. Lymphocytes enriched at the interface between a 40 and 70% Percoll gradient were collected.

Flow cytometry analysis of CD3+ and CD4+ T cells

Flow cytometry was performed as previously described, using 1 million cells per mouse (30). Lamina propria lymphocytes collected from Percoll gradients were preincubated with an FcγR blocking monoclonal mAb (10 μg/mL) (2.4G2, BD Pharmingen) for 5 min at 4 °C. To measure the proportion of CD3+ and CD4+ T-cells, sample contents were stained with both fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled (5 μg/mL) anti-CD3 (145-2C11, hamster IgG1, BD Pharmingen) and phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti CD4 (10 μg/mL) (GK1.5, rat IgG2b, BD Pharmingen). Flow cytometric analysis was conducted on a fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-Calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry systems) and analyzed using the CELLQUEST analysis program.

Eicosanoid and phospholipid profiles

Colonic mucosal scrapings were collected and immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Samples were extracted using the method of Yang et al (31). Briefly, aliquots (20 mL) of 1 N citric acid and of 2.5 μL of 10% BHT were added to samples to prevent free radical peroxidation. Prior to extraction, an aliquot of deuterated eicosanoids (PGE2-d4, 15-HETE-d8, 12-HETE-d8, and 13-HODE-d4) (100 ng/mL) was added to each sample as internal standards. Eicosanoids were subsequently extracted with 2 mL of hexane:ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v) and vortexed for 2 min. Samples were then centrifuged at 1800 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The upper organic layer was collected and the organic phases from three extractions were pooled, and then evaporated to dryness under a stream of nitrogen at room temperature. All extraction procedures were performed under low-light and low-temperature conditions to minimize potential photooxidation or thermal degradation of eicosanoid metabolites. Samples were then reconstituted in methanol: 10 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 8.5 (70:30, v/v) prior to LC/MS/MS analysis. The extracted prostaglandins were quantified using a LC/MS/MS Quattro Ultima tandem mass spectrometer (Waters Corp.) equipped with an Agilent HP 1100 binary pump HPLC inlet (Agilent Technologies). The prostaglandins were separated using a 2 × 150 mm Luna 3 m phenyl-hexyl analytical column (Phenomenex). The mobile phase consisted of 10 mM ammonium acetate, pH 8.5, and methanol. The column temperature was maintained at 50°C, and samples were kept at 4°C during the analysis. Individual analytes were detected using electrospray negative ionization and multiple reaction monitoring of the transitions m/z 351 → 271 for PGE2, m/z 349 → 269 for PGE3, and m/z 355 → 275 for PGE2-d4. Fragmentation of all compounds was performed using argon as the collision gas at a collision cell pressure of 2.10 × 10−3 Torr. The identification of each prostaglandin was confirmed by comparison to authentic reference standards. Total phospholipids from scraped colonic mucosa and splenic CD4+ T-cells were analyzed by gas chromatography as previously described (32).

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences between experimental groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA (SPSS software package). P-values less than 0.05 was accepted as significant.

Results

Weight gain

For AOM/DSS treated animals, neither carcinogen nor fat-1 genotype significantly altered weight gain (starting weight, wt 35.9 ± 3.0 g vs fat-1 37.7±2.9; final weight, wt 35.2±3.4 vs fat-1 36.8±3.2), n=19, p > 0.05.

Fatty acid profiles in fat-1 and wild type mice

Both fat-1 transgenic and wt offspring were fed a 10% safflower oil diet enriched in n-6 PUFA throughout the duration of the study. Colonic mucosa and splenic CD4+ (systemic) T-cell total lipid fatty acid compositional analyses revealed an increase in EPA (20:5 n-3), DPA (22:5 n-3) and DHA (22:6 n-3) in fat-1 transgenic mice (Supplemental Tables 2&3). In addition, the ratio of n-6 PUFA (20:4 n-6, 22:4 n-6, and 22:5 n-6) to the long-chain n-3 PUFA (20:5 n-3, 22:5 n-3, and 22:6 n-3) was significantly (P<0.05) suppressed in fat-1 T-cells and colonic mucosa (2.44 and 2.70), respectively, compared to wt mice (56.06 and 18.24). These data indicate that an appropriate activity of n-3 fatty acid desaturase was present and that relevant cell types, e.g., T-cells and colonocytes, were enriched in n-3 PUFA.

Suppression of colorectal tumorigenesis in fat-1 mice following azoxymethane (AOM) and dextran sodium sulphate (DSS) treatment

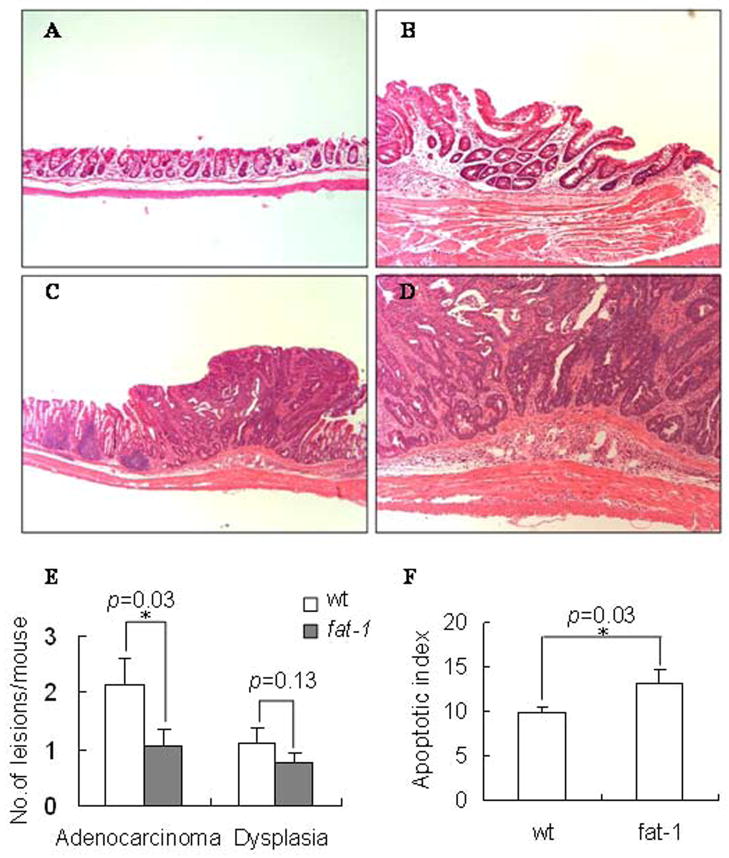

Colitis associated colonic tumors were induced by a single injection of AOM followed by repeated cycles of DSS ingestion using a well established protocol (25). Mice were terminated 12 wk after completion of the final DSS cycle and grossly visible masses/lesions were typed as adenomas, adenocarcinomas and dysplasia (Figure 1, A–D). The incidence of colonic tumors (adenocarcinomas) was lower in fat-1 relative to wt mice, 15 out of 19 (79%) for fat-1 vs 17 of 17 (100%, p=0.001) for wt mice. Fat-1 mouse tumors on average tended to be smaller (12.53±1.31 vs 14.11±2.02 mm2, p=0.09) compared to wt mice. In addition, fat-1 mice (n=19) exhibited a reduced average number of adenocarcinomas (1.05±0.29 vs 2.12±0.51, p=0.033) and dysplasia (0.75±0.19 vs 1.12±0.26, p=0.13) per mouse compared to wt mice (Figure 1 E).

Figure 1. Effect of fat-1 genotype on colonic adenocarcinomas and apoptosis levels.

Animals were injected with AOM followed by 3 cycles of DSS in order to induce colitis-associated colon tumors. Animals were terminated 12 wk after completion of the final DSS cycle. Representative histopathological features of hematoxylin and eosin-stained colorectal adenocarcinomas are shown. The lesions were counted on high-resolution photographs of the colons, (A) normal colon, 100x; (B) dysplasia, 100x; (C–D) adenocarcinoma, 40x and 100x. (E) Values represent mean ± SE, n=17–20 mice per treatment. (F) Apoptosis levels in fat-1 vs wild type mouse colon 38 d after the final DSS treatment. Data are expressed as an apoptotic index, i.e., the total number of apoptotic cells per 100 crypts. Values represent mean ± SEM, n=17–20 mice per treatment.

Omega-3 desaturase expression enhances apoptosis in colonic epithelial cells

Measurements of apoptosis have greater prognostic value to detect dietary effects on colon tumor incidence than do measurements of cell proliferation (14, 17). Therefore, apoptosis was assessed in the colonic epithelium (Figure 1 F). The apoptotic index was significantly (p=0.03) higher in fat-1 compared to wt mice, suggesting that the observed reduction in tumor incidence (described above) may in part be explained by an increase in apoptosis.

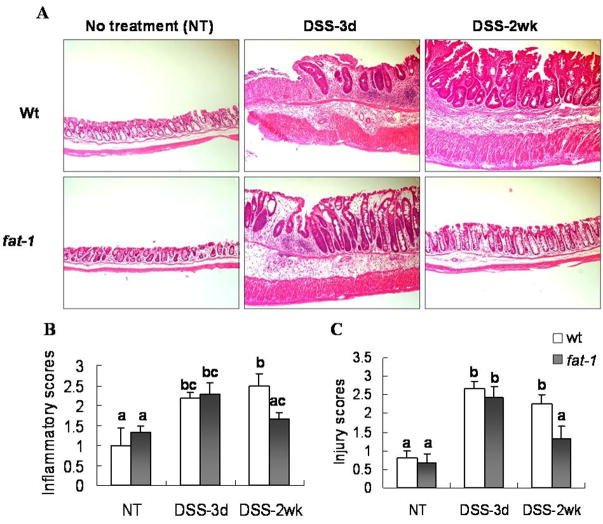

Fat-1 mice are less susceptible to DSS-induced chronic inflammation

In complimentary experiments, we also determined the ability of n-3 PUFA to modulate susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis. Both acute and chronic colitis was assessed by administering 2.5% DSS in the drinking water for 5 d, followed by a recovery period of 3 d (acute) or 2 wk (chronic). DSS administration was associated with a significant (P<0.05) loss of body weight and a reduced colon length (data not shown). Histological evaluation was subsequently performed in order to access immune cell infiltration and epithelial injury (Figure 2 A). After 3 d of recovery, there was no effect of n-3 PUFA with respect to the acute phase inflammatory score or the severity of injury (Figures 2 B&C). In contrast, following a 2 wk recovery period, colonic inflammation scores returned to pretreatment levels relative to 3 d recovery only in fat-1 mice, 2.29±0.29 to 1.67±0.17, p=0.03; as compared to wt mice, 2.17±0.17 to 2.50±0.29, p=0.21. Similar trends were observed with regard to injury scores: 2.43±0.30 to 1.33±0.33 in fat-1 mice, p=0.003; vs 2.67±0.21 to 2.25±0.25, in wt mice, p=0.19. Since DSS treatment followed by a 2 wk recovery period represents a chronic inflammation model in C57BL6 mice (33), these data suggest that fat-1 mice exhibit an enhanced long-term resolution of inflammatory processes.

Figure 2. Histological features of colonic inflammation and mucosal injury.

To explore the effect of n-3 PUFA on DSS-induced colonic inflammation and mucosal injury, mice were treated with a single 5 d cycle of DSS followed by either a 3 d or 2 wk recovery period. (A) Representative hematoxylin and eosin-stained colonic tissues from mice with or without 2.5% DSS treatment based on degrees of inflammatory cell infiltration and epithelial injury, 40x. Inflammatory scores (B) and injury scores (C) represent mean ± SEM, n=5–8 mice per treatment. Data not sharing common letters are significantly different, P < 0.05.

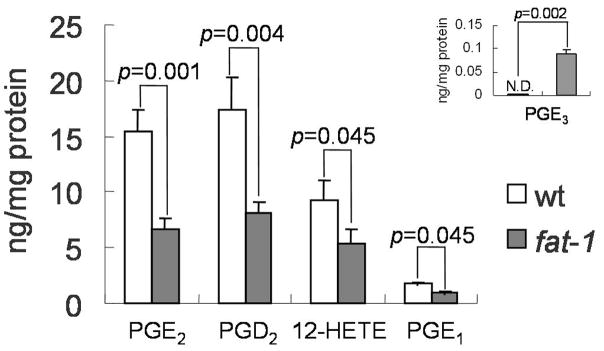

Eicosanoid profiles following AOM/DSS exposure

Since arachidonic acid (20:4 n-6) derived 2-series prostaglandins appear to promote cancer development in the colon (34), we also examined key eicosanoids in colonic mucosa following AOM/DSS exposure. Both n-3 and n-6 PUFA derived metabolites were assayed, including PGE2, PGD2, LTB4, 15-HETE, 12-HETE,

5-HETE, PGF2 alpha, PGE1, PGE3, 13-HODE, 13,14-dihydro-15-keto-PGE2, 13, 14-dihydro-15-keto-PGD2, 12HHTrE, LTB5, 5-HEPE, 12-HEPE and 15-HEPE. In general, n-6 PUFA derived eicosanoids (PGE2, PGD2, PGE1 and 12-HETE) were significantly reduced in fat-1 mice (Figure 3). In contrast, PGE3, an EPA-derived prostaglandin was elevated in fat-1 mice. No changes were observed with respect to LTB4, 15-HETE, 5-HETE, PGF2 alpha, PGE3, 13-HODE,

Figure 3. Colonic mucosa eicosanoid profiles of fat-1 and wild-type mice.

Animals were injected with AOM followed by 3 cycles of DSS and terminated 12 wk after completion of the final DSS cycle. Eicosanoids from scraped colonic mucosa were immediately extracted and quantified by LC/MS/MS. Insert: Elevated EPA-derived PGE3 in fat-1 mice, N.D., not detectable. Values are means ± SEM, n=8 mice per treatment. Levels of n-6-derived eicosanoids were significantly decreased in fat-1 mice.

13,14-dihydro-15-keto-PGE2, 13, 14-dihydro- 15-keto-PGD2, 12HHTrE, LTB5, 5-HEPE, 12-HEPE and 15-HEPE (data not shown). These results indicate that the enhanced incorporation of n-3 PUFA into fat-1 mouse colonic mucosa suppressed n-6 PUFA derived cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase metabolism.

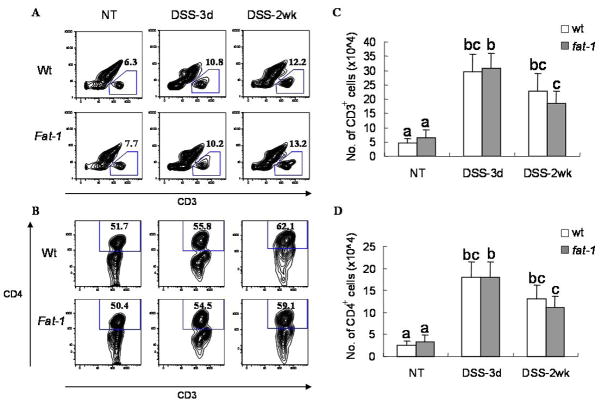

Altered infiltration of CD3+ and CD4+ T-cells in fat-1 mice after DSS exposure

A pathogenic role for CD4+ T-cells has been demonstrated with respect to the DSS induced inflammatory bowel disease (35, 36). Therefore, in order to contrast and compare local immunological features in fat-1 and wt mice, colonic lamina propria lymphocytes (LPL) were isolated from mice before and after a single dose of DSS (3 d and 2 wk of recovery period). Notably, there was a dramatic increase in the number of LPL and macrophages in both fat-1 and wt animals following DSS treatment (Supplemental Figures 1&2). Interestingly, only fat-1 mice exhibited a return to pretreatment levels after 2 wk of recovery. This suggests an inflammation-prone status in intestines from wt mice. For the purpose of examining the specific reactivity of lymphoid elements in the intestine, CD3+ T-cells and CD4+ T-helper cells from colonic lamina propria were quantified by flow cytometry (Figure 4). Comparison of 3 d vs 2 wk recovery time points revealed that fat-1 mice exhibited decreased CD3+ T cells numbers (×105) per colon (3.08±0.53 to 1.84±0.43, p=0.03 in fat-1 mice, 2.95±0.61 to 2.27±0.61, p=0.18 in wt mice) and CD4+ T helper cells numbers (1.80±0.35 to 1.12±0.25, p=0.048 in fat-1 mice, 1.78±0.37 to 1.30±0.32, p=0.13 in wt mice). These results suggest that the anti-tumorigenic effect of n-3 PUFA may be mediated in part via its immunosuppressive/anti-inflammatory properties.

Figure 4. Flow cytometric analysis of CD3+ and CD4+ colonic lamina propria lymphocytes (LPLs).

Mice were exposed to a single 5 d cycle of DSS followed by either a 3 d or 2 wk recovery period and LPLs were isolated from the colon. (A) Plots were gated on CD3+ expressing cells. The number in each image indicates the percentage of CD3+ cells. (B) Values are means ± SEM, n=5 mice per treatment. (C) Plots were gated on CD4+ cells within the CD3+ population. The number in each image indicates the percentage of CD4+ cells. (D) fat-1 mice exhibited a decreased number of CD3+ and CD4+ cells in lamina propria after 2 wk of recovery compared to 3 d. Data not sharing common letters are significantly different, P < 0.05, and are from 2 experiments, n=14–18 per treatment per experiment.

Discussion

Dietary n-3 PUFA is well known for both their anti-inflammatory and tumor suppressing properties (11, 37, 38). With respect to colon cancer development, we have demonstrated that the chemoprotective effect of fish oil is due to the direct action of n-3 PUFA and not to a reduction in the content of n-6 PUFA (8). Despite compelling data indicating a functional link between inflammation and colon cancer, the effects of n-3 PUFA on the pathways regulating initiation and maintenance of inflammation during colon cancer development remain poorly understood. Therefore, we examined the phenotype of fat-1 mice, which synthesize high tissue levels of n-3 PUFA (21), in order to test the hypothesis that the endogenous production of n-3 PUFA affords protection against colitis-associated colon carcinogenesis. Our data demonstrate that n-3 PUFA effectively alter colonic membrane phospholipid composition in the fat-1 mouse (Supplemental Table 3) resulting in the suppression of inflammation-driven tumor formation (Figure 1). These findings support our postulate that n-3 PUFA have chemoprotective properties. In addition, colonocyte apoptosis was elevated in fat-1 mice. This is noteworthy because apoptosis is progressively inhibited during colon cancer development (39). It is possible, therefore, that the observed protective effect of n-3 PUFA is due in part, to the enhanced deletion of cells though the activation of targeted apoptosis (8, 17).

It is well established that microbially-driven chronic inflammation can lead to colon cancer (38). Conditions which reduce mucosal barrier integrity, e.g., DSS, promote the production of proinflammatory cytokines which act in a paracrine fashion to promote angiogenesis and tumor growth (40). These mediators can in turn promote cyclooxygenase-2 related signaling pathways, which are capable of enhancing cell proliferation, angiogenesis, cell migration and invasion, while inhibiting apoptosis (34). Therefore, it is noteworthy that eicosanoid levels in colonic mucosa were significantly suppressed in fat-1 relative to wild type mice (Figure 3). This finding is consistent with the well documented ability of n-3 PUFA (EPA and DHA) to supplant arachidonic acid and subsequently antagonize prostaglandin (PGE2 and PGD2) and hydroxy fatty acid (12-HETE) biosynthesis (41).

Although the subject of much debate, there is growing evidence that n-3 PUFA suppress IBD in humans (7, 42). Since an inability to maintain an appropriate balance of T-cell subsets is a critical component contributing to the development of IBD (1, 43), and anti-inflammatory therapy is efficacious against neoplastic progression and malignant conversion, we specifically determined the susceptibility of fat-1 mice to DSS-induced chronic inflammation. Our studies reported herein have demonstrated that fat-1 mice exhibit an enhanced ability to resolve chronic colitis. Similar effects of n-3 PUFA were observed in previous acute inflammation experiments using this model (10, 44) as well as the interleukin 10 null mouse colitis model (38), although, a previous report has described contrasting data (45). Of relevance to the immune system in the intestine, we have shown that n-3 PUFA alter the balance between CD4+ T-helper (Th1 and Th2) subsets by directly suppressing Th1 cell development (30). This is noteworthy, because Th1 cells in part mediate IBD onset and progression (38, 43). Collectively, these observations suggest that n-3 PUFA dampen the persistent inflammation and immune activation that are associated with DSS-induced mucosal ulceration, thereby suppressing epithelial carcinogenesis.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that endogenously synthesized n-3 PUFA suppress colonic (i) chronic inflammation and tissue injury, (ii) specific activity of lymphoid and macrophage elements in the intestine, and (iii) tumor formation. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that n-3 PUFA, which are incorporated into both colonocytes and T-cells, suppress inflammation-driven tumor progression. Further understanding of the effects of fatty acids on the bidirectional interactions between colonocytes and T-cells in the lamina propria will provide insight into the ability of n-3 PUFA to favorably modulate the inflammation-dysplasia-carcinoma axis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by NIH grants CA59034, CA129444, DK071707, P30ES09106 and USDA CSREES 2006-34402-17121 “Designing Foods for Health”. We thank Dr. Nengtai Ouyang for assistance with immunohistobiochemestry methodology.

Abbreviations

- AOM

azoxymethane

- DSS

dextran sulfate sodium

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- FACS

fluorescence activated cell sorting

- HBSS

Hank’s Buffered Salt Solution

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- LPL

lamina propria lymphocytes

- Na4EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tetrasodium salt dehydrate

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated nick end labeling

References

- 1.Mudter J, Neurath MF. Mucosal T cells: mediators or guardians of inflammatory bowel disease? Curr. Opin Gastroenterol. 2003;19:343–49. doi: 10.1097/00001574-200307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Itzkowitz SH, Yio X. Inflammation and cancer IV. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: the role in inflammation. Am J Physiol. 2004;287:G7–G17. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00079.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. New Engl J Med. 2002;347:417–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubin DT, Kavitt RT. Surveillance for cancer and dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2006;35:581–604. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer Statistics 2007 CA Cancer J. Clinicians. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stenson WF, Cort D, Rodgers J, et al. Dietary supplementation with fish oil in ulcerative colitis. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:609–14. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-8-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belluzzi A, Boschi S, Brignola C, Munarini A, Cariani G, Miglio F. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(suppl):339S–42S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.1.339s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson LA, Nguyen DV, Hokanson RM, et al. Chemopreventive n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids reprogram genetic signatures during colon cancer initiation and progression in the rat. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6797–804. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prescott SM, Stenson WF. Fish oil fix. Nature Med. 2005;11:596–98. doi: 10.1038/nm0605-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudert CA, Weylandt KH, Lu Y, et al. Transgenic mice rich in endogenous omega-3 fatty acids are protected from colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:11276–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601280103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy BS. Chemoprevention of colon cancer by dietary fatty acids. Cancer Metas Rev. 1994;13:285–302. doi: 10.1007/BF00666099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anti M, Giancarlo M, Armelao F, et al. Effect of ω-3 fatty acids on rectal mucosal cell proliferation in subjects at risk for colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:883–91. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90021-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anti M, Armelao F, Marra G, et al. Effects of different doses of fish oil on rectal cell proliferation in patients with sporadic colonic adenomas. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1709–18. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90811-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang WC, Chapkin RS, Lupton JR. Predictive value of proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis as intermediate markers for colon tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:721–30. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.4.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng J, Ogawa K, Kuriki K, et al. Increased intake of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids elevates the level of apoptosis in the normal sigmoid colon of patients polypectomized for adenomas/tumors. Cancer Lett. 2003;193:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0304383502007176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whelan J, McEntee MF. Dietary (n-6) PUFA and intestinal tumorigenesis. J Nutr. 2004;134:3421S–26S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3421S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong MY, Lupton JR, Morris JS, et al. Dietary fish oil reduces DNA adduct levels in rat colon in part by increasing apoptosis during tumor initiation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers & Prev. 2000;9:819–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Courtney ED, Mathews S, Finlayson C, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) reduces crypt cell proliferation and increases apoptosis in normal colonic mucosa in subjects with a history of colorectal adenomas. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:765–76. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spector AA. Essentiality of fatty acids. Lipids. 1999;34:S1–S3. doi: 10.1007/BF02562220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang ZB, Ge Y, Che Z, et al. Adenoviral gene transfer of Caenorhabditis elegans n-3 fatty acid desaturase optimizes fatty acid composition in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:4050–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061040198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang JX, Wang J, Wu L, Kang ZB. Fat-1 mice convert n-6 to n-3 fatty acids. Nature. 2004;427:504. doi: 10.1038/427504a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper HS, Murthy S, Kido K, Yoshitake H, Flanigan A. Dysplasia and cancer in dextran sulfate sodium mouse colitis model. Relevance to colitis-associated neoplasia in the human: a study of histopathology, β-catenin and p53 expression and the role of inflammation. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:757–68. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.4.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seril DN, Liao J, Yang GY, Yang CS. Oxidative stress and ulcerative colitis-associated carcinogenesis: studies in humans and animal models. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:353–62. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okayasu I, Ohkusa T, Kajiura K, Kanno J, Sakamoto S. Promotion of colorectal neoplasia in experimental murine ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1996;39:87–92. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, et al. Ikkβ links inflammation and tumoringenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell. 2004;118:285–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma DW, Finnell RH, Davidson LA, et al. Folate transport gene inactivation in mice increases sensitivity to colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:887–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gavriel Y, Sherman Y, Ben-Sasson SA. Identification of programmed cell death in situ via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:493–501. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sund M, Xu L, Rhaman A, Qian BF, Hammarstrom ML, Danielsson A. Reduced susceptibility to dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis in the interleukin-2 heterozygous (IL-2+/−) mouse. Immunology. 2005;114:554–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolar SS, Barhoumi R, Callaway ES, et al. Synergy between docosahexaenoic acid and butyrate elicits p53-independent apoptosis via mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation in colonocytes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G935–G943. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00312.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang P, Kim W, Zhou RL, et al. Dietary fish oil inhibits antigen-specific Th1 cell development by suppression of clonal expansion. J Nutr. 2006;136:2391–98. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.9.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang P, Chan D, Felix E, et al. Determination of endogenous tissue inflammation profiles by LC/MS/MS: COX- and LOX-derived bioactive lipids. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;75:385–95. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan YY, Ly LH, Barhoumi R, McMurray DN, Chapkin RS. Dietary docosahexaenoic acid suppresses T-cell protein kinase C-theta lipid raft recruitment and interleukin-2 production. J Immunol. 2004;173:6151–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.6151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melgar S, Karlsson A, Michaelsson E. Acute colitis induced by dextran sulfate sodium progresses to chronicity in C57BL/6 but not in BALB/c mice: correlation between symptoms and inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G1328–38. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00467.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buchanan FG, DuBois RN. Connecting Cox-2 and Wnt in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:6–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sartor RB. Mechanisms of disease: pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3:390–407. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strober W, Fuss IJ, Blumberg RS. The immunology of mucosal models of inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:495–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chapkin RS, McMurray DN, Lupton JR. Colon cancer, fatty acids and anti-inflammatory compounds. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:48–54. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32801145d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chapkin RS, Davidson LA, Ly L, Weeks BR, Lupton JR, McMurray DN. Immunomodulatory effects of (n-3) fatty acids: putative link to inflammation and colon cancer. J Nutr. 2007;137:200S–04S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.1.200S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bedi A, Pasricha PJ, Akhtar AJ, et al. Inhibition of apoptosis during development of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1811–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ancrile B, Lim KH, Counter CM. Oncogenic ras-induced secretion of IL6 is required for tumorigenesis. Genes & Dev. 2007;21:1714–19. doi: 10.1101/gad.1549407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith WL. Cyclooxygenases, peroxide tone and the allure of fish oil. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:174–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turner D, Zlotkin SH, Shah PS, Griffiths AM. Omega 3 fatty acids (fish oil) for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2007;2:1–17. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006320.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mudter J, Neurath MF. Apoptosis of T cells and the control of inflammatory bowel disease: therapeutic implications. Gut. 2007;56:293–303. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.090464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nowak J, Weylandt KH, Habbel P, Wang J, Dignass A, Glickman JN, Kang JX. Colitis-associated colon tumorigenesis is suppressed in transgenic mice rich in endogenous n-3 fatty acids. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1991–1995. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hegazi RA, Saad RS, Mady H, Matarese LE, O’Keefe S, Kandil HM. Dietary fatty acids modulate chronic colitis, colitis-associated colon neoplasia and COX-2 expression in IL-10 knockout mice. Nutrition. 2006;22:275–82. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.