Introduction

Prediction equations for coronary heart disease (CHD) risk are useful tools that inform clinicians and patients about the absolute risk for developing CHD. A basic principle in CHD prevention is that the intensity of risk-reducing interventions should be based on the individual patient’s absolute CHD risk. In the current era of HIV infection and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), knowing one’s CHD risk and acting to reduce it has become imperative to long-term survival. Given the increased life expectancy due to HAART, more HIV infected persons will experience complications not related to HIV per se, and will reach an age where they are at increased risk for developing CHD.

However, existing CHD risk prediction equations were not developed in HIV-infected adults or children. In the general population, CHD risk prediction models derived from the Framingham Heart Study estimate the risk of total CHD (angina pectoris, myocardial infarction (MI), coronary heart disease death)1, or estimate the risk for hard CHD endpoints (MI, coronary heart disease)2. The traditional risk factors used to predict CHD risk and how risk factor alterations affect CHD outcomes in HIV-infected and HIV-seronegative people are summarized in Table 1. The estimates of the relative effects of traditional risk factors on CHD outcomes appear similar between HIV and non-HIV-infected patients. However, they are based on only two studies in HIV-infected patients. While traditional CHD risk factors may operate in the same manner in HIV patients as in the general population, there may still be a need to identify and evaluate HIV-specific CHD risk factors and equations, refine existing CHD prediction equations, and develop new HIV-specific CHD prediction equations for adults, adolescents and children. To date, Framingham CHD risk predictions have performed reasonably well when applied to HIV-infected patients. We need to evaluate whether new HIV-specific CHD risk prediction approaches perform better than existing algorithms. This represents a formidable challenge, but is crucial to improve care and reduce health care costs for people living with HIV.

Table 1.

Do traditional main cardiovascular risk factors predict the risk of CAD/CVD in HIV-infected (HIV+) similarly to HIV-uninfected (HIV−) persons?

| % Increase in risk per unit for each study | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV risk factor | Unit | HIV+(14,36) | HIV− (49–54) | |

| Age | per 1 year older | 9% | 6% | 6%–9% (7) |

| Sex | Male vs female | n.s. | 110% | 110%–160% (2) |

| Diabetes | Yes vs. no | 260% | 90% | 140%–252% (3) |

| Smoking | Yes vs. no. | 140% | 290% | 70%–290% (3) |

| Hypertension | Yes vs no | 30% | 80% | 80%–90% (3) |

| Total cholesterol | per 1 mmol/L# ↑ | - | 26% | 25%–33% (3) |

| HDL-cholesterol | per 1 mmol/L# ↑ | - | −28% | −52% (1) |

Adapted from J.Lundgren (Chicago June 2007).

( ) =number of studies considered.

1 mmol/L = 39 mg/dL

Existing CHD Prediction Equations

Historically, CHD prediction equations have been derived to estimate risk for an initial coronary event in a population with minimal coronary heart disease risk at the beginning of the observation period 1,3,4, generally from data obtained in middle-aged adults. Such equations may not provide suitable predictions for young people living with HIV. Of concern, adolescents have been and continue to be infected with HIV, and despite substantial reductions in mother-to-child transmission in the US, infants in resource-limited regions of the world continue to be infected with HIV and adolescents continue to experiment with intravenous drugs, share needles, and engage in unprotected sex. Existing equations predict the 10-yr CHD risk based upon longitudinal observational data. Observational data are limited in their ability to predict adverse events 5. HIV was identified in the 1980’s, and HAART has only been available for ~10yrs, so predicting 10-yr CHD risk with limited HAART experience will challenge existing CHD prediction equations.

Despite these limitations, existing CHD prediction algorithms have been applied to HIV-infected people 6–13 and have performed reasonably well 14,15,16,17. Of note, there appears to be a significant, but modest concordance among 3 popular CHD risk stratification algorithms when applied to HIV 10. For the time being, it appears the Framingham Risk Score calculator (http://hp2010.nhlbihin.net/atpiii/calculator.asp) can be used effectively to rank CHD risk in HIV-infected people; the only information required is age, smoking status, and fasting lipid profile. Most 6–9, but not all studies 11,13 found a slightly greater CHD risk in HIV-infected people taking HAART and experiencing abnormal adipose tissue distribution, when compared to ‘matched’ HIV-seronegative controls. The contribution of type and duration of individual anti-HIV drugs, and their differential effects on serum lipids/lipoproteins to CHD risk are still debated 14,17–20,21,22,23. When actual CHD events (acute MI, cardiac death) are documented, the limited data suggest that CHD risk factors were more prevalent, and acute MI rates were higher in HIV compared to age matched non-HIV patients 12,14,20,24 (Fig. 1). In these reports, however, the absolute risk of MI was low compared with the known benefits of HAART in terms of reducing AIDS-related mortality 21,25,26. Given the limitations of existing CHD prediction equations, the evolving nature of the cardiometabolic syndrome in HIV, and the relative infancy of this area of inquiry, it is important to grasp this window of opportunity and move forward with the refinement of existing or development of new HIV-specific CHD prediction equations.

Fig 1. (From Triant et al., 24).

Acute MI rates (events/1000 patient years) were increased with advancing age in HIV compared with non-HIV patients. Grey line = HIV infected. Black line = HIV-seronegative control group. Both genders included.

HIV-Specific CHD Risk Factors

Whether HIV infection per se is an independent CHD risk factor, or the increased CHD risk is solely due to HAART, remains controversial. CHD risk is increased in autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus 27,28, so HIV-related chronic proinflammatory processes and altered immune function may impart greater CHD risk than in the general population. Even prior to HAART availability, HIV infection was associated with a proatherogenic lipid profile; low HDL, elevated small dense LDL particles and triglyceride levels 29,30. However, it may be difficult to delineate among CHD risk associated with HIV per se, HAART, and traditional risk factors, because the vast majority of the HIV-infected patients will receive HAART in the course of their disease.

Among traditional CHD risk factors, the prevalence and intensity of substance abuse (esp. tobacco and recreational drugs) are greater in patients with HIV than in the general population 6–8,11–13,31–33. In HIV, HAART, other medications, and poor lifestyle/behavioral choices (diet, physical inactivity, and substance abuse) may adversely affect (directly and indirectly) traditional coronary risk factors: lipid/lipoprotein levels, regional adipose tissue distribution, and insulin sensitivity. The increased CHD risk seen in some patients on HAART may primarily be related to the effects of HAART on traditional CHD risk factors. But other, yet unidentified mechanisms, may also contribute to the increased CHD risk (e.g., direct effect of HAART on the vasculature)34. Evidence from the D:A:D and other studies indicates that increased duration of protease inhibitor (PI) therapy leads to an increase in the rate of cardiovascular disease events 20,35,36. HAART regimens are changed frequently and each drug within a class (nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, protease inhibitors) is associated with very different effects on traditional CHD risks factors 8,37–39. New anti-HIV drugs and drug classes (entry, fusion, integrase and maturation inhibitors) are continuously introduced. HAART prescribing practices are dynamic, variable and complicated, and it is not certain if they should be included in HIV-specific CHD risk prediction models. Such models are under development 8,16,22. Conversely, we may need several, separate CHD risk algorithms for people living with HIV (i.e., HAART-naïve, history of HAART exposure, discontinued HAART, children, and adolescents). Finally, HIV is a global epidemic and CHD prediction models will need to be adapted to these markedly different geographical, ethnic and racial variations 14,40.

Refining Existing Prediction Equations

The starting point for the development of a CHD risk prediction equation in patients with HIV is a comprehensive medical history and clinical examination with standardized collection of key predictor (independent) risk factors: age, sex, fasting lipids (total-, LDL-, HDL-cholesterol, total/HDL ratio), systolic blood pressure, history of diabetes mellitus treatment, fasting or postprandial glucose levels, use of tobacco and other substances 1,4,28. Most existing equations predict coronary heart disease morbidity (new MI, ischemic events including stroke, coronary artery angioplasty, bypass surgery, carotid endarterectomy) and mortality (cardiac death). Such endpoints need to be defined a priori and captured in data collection (dependent variables). Baseline risk factors and treatments for hypertension, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia and other conditions need to be captured. In particular, specialized models have been developed for persons with type 2 diabetes that consider additional potential predictor variables; hemoglobin A1cc, microalbuminuria, and duration of diabetes 41–43. In HIV, a challenge will be to allow for a higher prevalence of lipid- and glucose-lowering, and antihypertensive therapies, as well as HIV-specific factors (i.e. HIV RNA, CD4 cell count, duration of disease and therapy).

In prospective studies, selecting risk factors, and developing and assessing the utility of a new CHD prediction model typically involves a proportional hazards regression model. The utility of the model can be assessed using several different performance measures. Relative Risk. For each risk factor, proportional hazards modeling yields regression coefficients for a study cohort. The relative risk of a variable is computed by exponentiation of the regression coefficient, and is a measure of the increased risk for someone with a given risk factor (e.g., tobacco use) compared with the risk for someone who doesn’t use tobacco. Discrimination. Discrimination is the ability of a prediction model to separate those who experience hard CHD events from those who do not. This is quantified by calculating the c statistic, analogous to the area under a receiver-operator characteristic curve 44. This value represents an estimate of the probability that a model assigns a higher risk to those who develop CHD within a specified follow-up than to those who do not. Calibration. Calibration measures how closely predicted outcomes agree with actual outcomes. For this, a version of the Hosmer-Lemeshow chi-square statistic is used 45. The chi-square statistic is used to compare the differences between predicted and actual event rates. Small values indicate good calibration and values >20 indicate significant lack of calibration. Recalibration. An existing CHD prediction model can be recalibrated if it systematically over- or under-estimates CHD risk in a new population, but correctly ranks subjects in terms of CHD risk. For example, recalibrating the Framingham risk prediction equation would involve inserting the mean risk factor values and average incidence rate for the new population into the Framingham equation. Kaplan-Meier estimates can be used to determine average incidence rates.

New CHD Prediction Equations for HIV

In HIV, estimates of CHD risk have been reported and calibrated by the D:A:D investigators 8,14,15,17 and others 20,22,24, and new HIV-specific CHD prediction algorithms have recently been proposed 16,21,31. The D:A:D-derived HIV-specific CHD risk equations incorporated protease inhibitor exposure and traditional CHD risk factors (e.g., age, tobacco use), and captured CHD events (incl. MI) as the dependent variable. Among 33,594 person-years, 157 CHD events occurred; the D:A:D equation predicted 153, while Framingham predicted 187 events. Framingham predicted remarkably well, but tended to underestimate CHD events in HIV+ tobacco users (Fig 2–3). The area under the D:A:D receiver-operator characteristic curve discrimination (ROC) statistic was 0.78 (95%CI = 0.75–0.82), and the D:A:D prediction equations were accurate in men vs women, and tobacco users vs non-users. Several lessons have been learned that can be applied going forward. The ROC discrimination statistic (0.78) was excellent and whether this can be improved upon, by including additional traditional or HIV-specific risk factors, needs to be evaluated. External validation of the D:A:D prediction model is warranted to determine whether it is generalizable among people living with HIV.

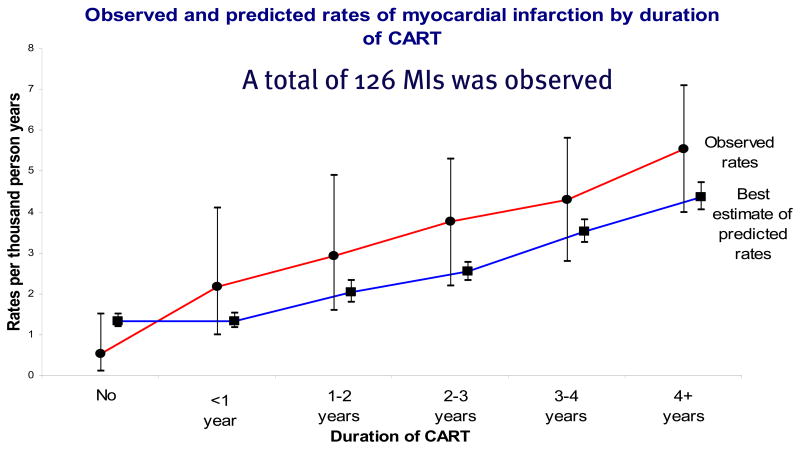

Fig 2. (From D:A:D 15).

Based on duration of HAART and the Framingham CHD risk prediction, CHD events were underpredicted in comparison to events observed in D:A:D. CHD events were MI according to the WHO-MONICA classification, monitored and verified by two independent physicians.

Fig 3. (From D:A:D16).

When subdivided on the basis of gender and tobacco use, Framingham CHD risk prediction appeared to under estimate observed CHD events in D:A:D for tobacco users, and over estimate CHD events for HIV-infected patients who reported never using tobacco. CHD events represent a composite endpoint including MI, invasive coronary artery procedure including coronary artery bypass, or angioplasty/stenting, or death from other coronary heart disease.

Finally, non-invasive, direct measures of carotid intima media thickness or brachial artery reactivity/dilatation have also been used to evaluate cardiovascular disease risk 46–48 in HIV-infected adults and children. In theory, these measures may provide more predictive value for premature atherosclerosis and CHD in HIV. In support of this, one study using multivariate models has reported that Framingham risk stratification independently predicted carotid intima media thickness in HIV-infected adults 46. This suggests that additional research should focus on the utility, sensitivity, and specificity of these and other non-invasive surrogate measures (coronary vessel imaging) of premature CHD in HIV, rather than waiting for the somewhat rare, but hard CHD outcomes like MI, stroke, endarterectomy, or cardiac death to occur.

Controversial Issues, Gaps in Knowledge and Future Research Priorities

Given limited data, the estimation of the relative effects of traditional risk factors on CHD outcomes appears similar between HIV-infected and non HIV-infected patients. To date, Framingham CHD risk predictions have performed reasonably well when applied to HIV-infected patients. There is an important need to identify HIV-specific risk factors, and test whether new HIV-specific CHD risk prediction approaches perform better than existing algorithms. In this regard, the following research needs and priorities were identified:

Perform a large, multi-center, multi-national prospective study that captures a core set of traditional and HIV-specific variables that are all collected at standard intervals in HAART-naïve and treated HIV-infected children, adolescents, and adults to determine with certainty the optimal HIV specific risk prediction algorithm and the relative contribution of HIV-infection and HAART to CHD in this population. Ideally such a study or related studies would obtain fundamental data on (1). The relative contribution of HIV-infection (replication, altered immunity, and inflammation), HAART component(s), central adiposity, peripheral lipoatrophy, metabolic dysregulation to CHD risk in HIV. (2). The safety and efficacy of standard treatments (diet, weight loss, physical activity), and more intensive therapies (anti-inflammatory agents, glucose-, lipid-, and blood pressure-lowering agents, switching HAART regimens) for CHD in HIV.

Consider the use of large administrative databases/registries as interim data sources to develop and refine HIV-specific CHD risk prediction equations, as a prospective study would require many years of follow-up. Participants should be enrolled from developed and resource-limited regions of the world where HAART regimens are more standardized.

Develop novel database integration techniques to combine ongoing cohorts and re-calibrate existing models (D:A:D, SMART, MACS, VA, ART, ACTG). A focus of current HIV observational and cohort studies should be the implementation of standardized, prospective, validated CHD endpoints together with core HIV markers and treatment, and traditional CHD risk factors to allow such integration to be undertaken.

Footnotes

Writing Group Members: Victor G. Davila-Roman (Washington University, St. Louis, MO)

Ralph B. D’Agostino, Sr. (Boston University, Boston, MA)

W. Todd Cade (Washington University, St. Louis, MO)

Tarek A. Helmy (University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH)

Matthew Law (National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia)

Kristin E. Mondy (Washington University, St. Louis, MO)

Sharon Nachman (SUNY Health Science Center at Stony Brook)

Linda R. Peterson (Washington University, St. Louis, MO)

Signe W. Worm (University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark)

Discussion Panel: Paul E. Sax, MD - Moderator - Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA

James B. Meigs, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA

Ralph D’Agostino, PhD, BU School of Medicine

Jim Neaton, Ph.D, University of Minnesota

Contributor Information

Morris Schambelan, UCSF, San Francisco, CA.

Peter W. F. Wilson, Emory, Atlanta, GA

Kevin E. Yarasheski, Washington University, St. Louis, MO

References

- 1.Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrario M, Chiodini P, Chambless LE, Cesana G, Vanuzzo D, Panico S, Sega R, Pilotto L, Palmieri L, Giampaoli S. Prediction of coronary events in a low incidence population. Assessing accuracy of the CUORE Cohort Study prediction equation. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:413–421. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Backer G, Ambrosioni E, Borch-Johnsen K, Brotons C, Cifkova R, Dallongeville J, Ebrahim S, Faergeman O, Graham I, Mancia G, Cats VM, Orth-Gomér K, Perk J, Pyörälä K, Rodicio JL, Sans S, Sansoy V, Sechtem U, Silber S, Thomsen T, Wood D European Society of Cardiology. American Heart Association. American College of Cardiology. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Third Joint Task Force of European and other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Atherosclerosis. 2004;173:381–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assman G, Cullen P, Schulte H. Simple scoring scheme for calculating the risk of acute coronary events based on the 10-year follow-up of the prospective cardiovascular Munster (PROCAM) study. Circulation. 2002;105:310–315. doi: 10.1161/hc0302.102575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes MD, Williams PL. Challenges in using observational studies to evaluate adverse effects of treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1705–1707. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergersen BM, Sandvik L, Bruun JN, Tonstad S. Elevated Framingham risk score in HIV-positive patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy: results from a Norwegian study of 721 subjects. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;23:625–630. doi: 10.1007/s10096-004-1177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Socio GVL, Martinelli L, Morosi S, Fiorio M, Roscini AR, Stagni G, Schillaci G. Is estimated cardiovascular risk higher in HIV-infected patients than in the general population? Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39:805–812. doi: 10.1080/00365540701230884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friis-Møller N, Weber R, Reiss P, Thiébaut R, Kirk O, d’Arminio Monforte A, Pradier C, Morfeldt L, Mateu S, Law M, El-Sadr W, De Wit S, Sabin CA, Phillips AN, Lundgren JD The DAD study group. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in HIV patients-association with antiretroviral therapy. Results from the D:A:D study. AIDS. 2003;17:1179–1193. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000060358.78202.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hadigan C, Meigs JB, Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Davis B, Basgoz N, Sax PE, Grinspoon S. Prediction of coronary heart disease risk in HIV-infected patients with fat redistribution. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:909–916. doi: 10.1086/368185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knobel H, Jerico C, Montero M, Sorli ML, Velat M, Guelar A, Saballs P, Pedro-Botet J. Global cardiovascular risk in patients with HIV infection: concordance and differences in estimates according to three risk equations (Framingham, SCORE, and PROCAM) AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007;21:452–457. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santos J, Palacios R, González M, Ruiz J, Márquez M. Atherogenic lipid profile and cardiovascular risk factors in HIV-infected patients (Nétar Study) Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:677–680. doi: 10.1258/095646205774357398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vittecoq D, Escaut L, Chironi G, Teicher E, Monsuez JJ, Andrejak M, Simon A. Coronary heart disease in HIV-infected patients in the highly active antiretroviral treatment era. AIDS. 2003;17:S70–76. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200304001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mondy K, Turner Overton E, Grubb J, Tong S, Seyfried W, Powderly W, Yarasheski K. Metabolic syndrome in HIV-infected patients from an urban, midwestern US outpatient population. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:726–734. doi: 10.1086/511679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The DAD Study Group. Friis-Møller N, Reiss P, Sabin CA, Weber R, Monforte A, El-Sadr W, Thiébaut R, De Wit S, Kirk O, Fontas E, Law MG, Phillips A, Lundgren JD. Class of antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1723–1735. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Law M, Friis-Møller N, Weber R, Reiss P, Thiebaut R, Kirk O, d’Arminio Monforte A, Pradier C, Morfeldt L, Calvo G, El-Sadr W, De Wit S, Sabin CA, Lundgren JD The DAD Study Group. Modelling the 3-year risk of myocardial infarction among participants in the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (DAD) study. HIV Med. 2003;4:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1293.2003.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friis-Møller N, Thiébaut R, Reiss P, El-Sadr W, Weber R, D’Arminio Monforte A, Fontas E, Worm S, Kirk O, Phillips A, Sabin CA, Lundgren JD, Law M The D:A:D Study Group. 14th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Los Angeles, CA: Poster 808; 2007. Predicting the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) in HIV-infected patients: The D:A:D CHD Risk Equation. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (DAD) Study Group. Combination antiretroviral therapy and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1993–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bozzette SA, Ake CF, Tam HK, Chang SW, Louis TA. Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in patients treated for human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:702–710. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grinspoon S, Carr A. Cardiovascular risk and body fat abnormalities in HIV-infected adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:48–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mary-Krause M, Cotte L, Simon A, Partisani M, Costagliola D Clinical Epidemiology Group from the French Hospital Database. Increased risk of myocardial infarction with duration of protease inhibitor therapy in HIV-infected men. AIDS. 2003;17:2479–2486. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200311210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phillips A, Carr A, Neuhaus J, Visnegarwala F, Prineas R, Burman W, Williams I, Drummond F, Duprez D, Lundgren JD, et al. for the SMART Study Group. 14th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Los Angeles, CA: Poster 41; 2007. Interruption of ART and risk of cardiovascular disease: findings from SMART. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan RC, Kingsley LA, Sharrett AR, Li X, Lazar J, Tien PC, Mack WJ, Cohen MH, Jacobson L, Gange SJ. Ten-year predicted coronary heart disease risk in HIV-infected men and women. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1074–1081. doi: 10.1086/521935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan RC, Tien PC, Lazar J, Zangerle R, Sarcletti M, Pollack TM, Rind DM, Sabin C, Friis-Moller N, Lundgren JD, Stein JH the Writing Committee of the DAD Study Group. Antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:715–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2506–2512. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stein JH. Cardiovascular risks of antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1773–1775. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe078037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reiss P. Editorial Comment::How bad is HAART for the HEART? AIDS. 2003;17:2529–2531. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200311210-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frostegard J. SLE, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. J Intern Med. 2005;257:485–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sattar N, McCarey DW, Capell H, McInnes IB. Explaining how “high-grade” systemic inflammation accelerates vascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation. 2003;108:2957–2963. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000099844.31524.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grunfeld C, Pang M, Doerrler W, Shigenaga JK, Jensen P, Feingold KR. Lipids, lipoproteins, triglyceride clearance, and cytokines in human immunodeficiency virus infection and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74:1045–1052. doi: 10.1210/jcem.74.5.1373735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feingold KR, Krauss RM, Pang M, Doerrler W, Jensen P, Grunfeld C. The hypertriglyceridemia of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is associated with an increased prevalence of low density lipoprotein subclass pattern B. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:1423–1427. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.6.8501146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.May M, Sterne JAC, Shipley M, Brunner E, d’Agostino R, Whincup P, Ben-Shlomo Y, Carr A, Ledergerber B, Lundgren JD, Phillips AN, Massaro J, Egger M. A coronary heart disease risk model for predicting the effect of potent antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infected men. Int J Epidemiol. 2007 doi: 10.1093/ije/dym135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seaberg EC, Muñoz A, Lu M, Detels R, Margolick JB, Riddler SA, Williams CM, Phair JP Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Association between highly active antiretroviral therapy and hypertension in a large cohort of men followed from 1984 to 2003. AIDS. 2005;19:953–960. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000171410.76607.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garofalo R, Mustanski BS, McKirnan DJ, Herrick A, Donenberg GR. Methamphetamine and young men who have sex with men: understanding patterns and correlates of use and the association with HIV-related sexual risk. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:591–596. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.6.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, Chai H, Yao Q, Chen C. Molecular mechanisms of HIV protease inhibitor-induced endothelial dysfunction [Review] J AIDS. 2007;44:493–499. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180322542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmberg SD, Moorman AC, Williamson JM, Tong TC, Ward DJ, Wood KC, Greenberg AE, Janssen RS HIV Outpatient Study (HOPS) investigators. Protease inhibitors and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with HIV-1. Lancet. 2002;360:1747–1748. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11672-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iloeje UH, Yuan Y, L’Italien G, Mauskopf J, Holmberg SD, Moorman AC, Wood KC, Moore RD. Protease inhibitor exposure and increased risk of cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected patients. HIV Med. 2005;6:37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown TT, Li X, Cole SR, Kingsley LA, Palella FJ, Riddler SA, Chmiel JS, Visscher BR, Margolick JB, Dobs AS. Cumulative exposure to nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors is associated with insulin resistance markers in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. AIDS. 2005;19:1375–1383. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000181011.62385.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tien PC, Schneider MF, Cole SR, Levine AM, Cohen M, Dehovitz J, Young M, Justman JE. Antiretroviral therapy exposure and incidence of diabetes mellitus in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. AIDS. 2007;21:1739–1745. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32827038d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asztalos BF, Schaefer EJ, Horvath KV, Cox CE, Skinner S, Gerrior J, Gorbach SL, Wanke C. Protease inhibitor-based HAART, HDL, and CHD-risk in HIV-infected patients. Atherosclerosis. 2006;184:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marrugat J, Subirana I, Comin E, Cabezas C, Vila J, Elosua R, Nam B-H, Ramos R, Sala J, Solanas P, Cordon F, Gene-Badia J, D’Agostino RB for the VERIFICA (Validez de la Ecuacion de Riesgo Individual de Framingham de Incidentes Coronarios Adaptada*) Investigators. Validity of an adaptation of the Framingham cardiovascular risk function: the VERIFICA study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:40–47. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.038505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mitchell BD, Haffner SM, Hazuda HP, Patterson JK, Stern MP. Diabetes and coronary heart disease risk in Mexican Americans. Ann Epidemiol. 1992;2:101–106. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(92)90043-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stevens RJ, Coleman RL, Adler AI, Stratton IM, Matthews DR, Holman RR. Risk factors for myocardial infarction case fatality and stroke case fatality in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 66. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:201–207. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hunt KJ, Williams K, Hazuda HP, Stern MP, Haffner SM. The metabolic syndrome and the impact of diabetes on coronary heart disease mortality in women and men: The San Antonio Heart Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:870–877. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB. Overall C as a measure of discrimination in survival analysis: model specific population value and confidence interval estimation. Stat Med. 2004;23:2109–2123. doi: 10.1002/sim.1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Goodness-of-fit tests for the multiple logistic regression model. Commun Statistics--Part A Theor Meth. 1980;A9:1043–1069. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jerico C, Knobel H, Calvo N, Sorli ML, Guelar A, Gimeno-Bayon JL, Saballs P, Lopez-Colomes JL, Pedro-Botet J. Subclinical carotid atherosclerosis in HIV-infected patients: role of combination antiretroviral therapy. Stroke. 2006;37:812–817. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000204037.26797.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnsen S, Dolan SE, Fitch KV, Kanter JR, Hemphill LC, Connelly JM, Lees RS, Lee H, Grinspoon S. Carotid intimal medial thickness in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women: effects of protease inhibitor use, cardiac risk factors, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4916–4924. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McComsey GA, O’Riordan M, Hazen SL, El-Bejjani D, Bhatt S, Brennan ML, Storer N, Adell J, Nakamoto DA, Dogra V. Increased carotid intima media thickness and cardiac biomarkers in HIV infected children. AIDS. 2007;21:921–927. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328133f29c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, Lisheng L. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu Y, Liu X, Li X, Li Y, Zhao L, Chen Z, Li Y, Rao X, Zhou B, Detrano R, Liu K for the USA-PRC Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular and Cardiopulmonary Epidemiology Research Group and the China Multicenter Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Epidemiology (China MUCA) Research Group. Estimation of 10-year risk of fatal and nonfatal ischemic cardiovascular diseases in Chinese adults. Circulation. 2006;114:2217–2225. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.607499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomsen TF, McGee D, Davidsen M, Jorgensen T. A cross-validation of risk-scores for coronary heart disease mortality based on data from the Glostrup Population Studies and Framingham Heart Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:817–822. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosengren A, Hagman M, Wedel H, Wilhelmsen L. Serum cholesterol and long-term prognosis in middle-aged men with myocardial infarction and angina pectoris: A 16-year follow-up of the Primary Prevention Study in Göteborg, Sweden. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:754–761. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mensah GA, Brown DW, Croft JB, Greenlund KJ. Major coronary risk factors and death from coronary heart disease: baseline and follow-up mortality data from the second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES II) Amer J Prev Med. 2005;29(Suppl 1):68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cooper JA, Miller GJ, Humphries SE. A comparison of the PROCAM and Framingham point-scoring systems for estimation of individual risk of coronary heart disease in the Second Northwick Park Heart Study. Atherosclerosis. 2005;181:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]