Abstract

Providing care for children with asthma can be demanding and time-intensive with far-reaching effects on caregivers’ lives. Studies have documented childhood asthma symptom reductions and improved asthma-related quality of life (AQOL) with indoor allergen-reducing environmental interventions. Few such studies, however, have considered ancillary benefits to caregivers or other family members. Ancillary benefits could be derived from child health improvements and reduced caregiving burden or from factors such as improved living environments or social support that often accompanies intensive residential intervention efforts. As part of the Boston Healthy Public Housing Initiative (HPHI), a longitudinal single-cohort intervention study of asthmatic children, we examined trends in caregivers’ quality of life related to their child’s asthma (caregiver AQOL) using monthly Juniper Caregiver Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaires (AQLQ) for 32 primary caregivers to 42 asthmatic children aged 4 to 17 years. Longitudinal analyses were used to examine caregiver AQOL trends and their relationship to the child’s AQOL, then to consider additional predictors of caregiver AQOL. Caregiver AQLQ improved significantly over the course of the study with overall improvements significantly correlated with child AQOL (p = 0.005). However, caregiver AQOL improved most in the months before environmental interventions, while children’s AQOL improved most in the months following. Time trends in caregiver AQOL, controlling for child AQOL, were not explained by available social support or caregiver stress measures. Our findings suggest potential participation effects not adequately captured by standard measures. Future environmental intervention studies should more formally consider social support and participation effects for both children and caregivers

Keywords: Urban childhood asthma, Quality of life, Environmental interventions, Psychological factors

Introduction

Providing care for children with asthma can be demanding and time-intensive with far-reaching effects on caregivers’ lives.1 Studies have shown significant improvements in children’s asthma symptoms with allergen-reducing indoor environmental interventions.2–5 These environmental intervention studies have evaluated numerous childhood asthma endpoints, including symptoms, symptom-days, lost sleep, missed school days, and lung function. However, few studies have considered ancillary benefits to caregivers from the child’s improved health and well-being; such caregiver benefits may include fewer disrupted plans, fewer missed work days, and less sleep lost. One community-based study of tailored indoor allergen-reducing interventions found significant caregiver asthma-related quality of life (AQOL) differences between low- and high-intensity intervention groups at 1 year,6 but did not have the necessary time-resolved data to examine caregiver AQOL trends toward understanding causal pathways for these improvements.

Generic and AQOL measures have been used as clinical markers for asthma severity,7 and validated children’s AQOL measures integrate multiple symptoms and related factors into one measure which can be tracked over time. Similarly, caregiver AQOL scales (caregivers’ quality of life as related to their child’s asthma) allow for the examination of ancillary benefits to caregivers and other household members.

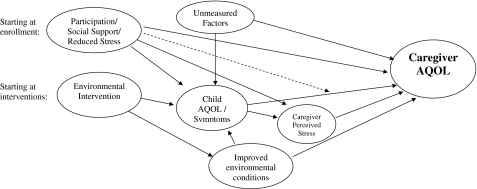

There are a number of reasons why environmental interventions to alleviate children’s asthma symptoms may also benefit caregivers. Caregiver benefits may be associated with the child’s AQOL improvements, but may also be derived from other aspects of the study. Our conceptual framework (Figure 1) includes multiple pathways through which a child-focused intervention study may improve caregiver AQOL. First, the child’s AQOL and symptom improvements may reduce caregiving demand and stress. Second, social support, received through study participation, may directly influence caregiver AQOL, an effect possibly mediated through reduced caregiver stress. Third, environmental interventions can improve living environments; many caregivers of asthmatics have atopic asthma themselves, and resultant health improvements could influence perceptions about their child’s asthma. Moreover, visible environmental improvements (e.g., reduced cockroach infestation) may influence caregiver perceptions. Finally, additional unmeasured factors, such as asthma education, may also improve caregivers’ sense of control and efficacy in managing asthma.

FIGURE 1.

A conceptual framework for investigating improvements in caregiver asthma-related quality of life associated with environmental interventions for reducing childhood asthma symptoms. The dotted line indicates the potential for social support to modify effects of caregiver stress. Additional pathways may also be relevant.

These various pathways suggest potential benefits from both psychosocial and environmental aspects of intensive residential environmental interventions, even when not directly targeting social support or related constructs. Social support is particularly relevant in community-based participatory research studies in socioeconomically disadvantaged or underserviced settings8,9 or studies involving frequent interaction between staff and caregivers. Relatedly, the perception of having needs met through environmental interventions may directly influence caregiver outlook and AQOL.

The purpose of this analysis is to examine caregiver AQOL over the course of an environmental intervention study aimed at improving asthmatic children’s health. Prior evidence indicates that social conditions may influence the health-related efficacy of environmental interventions. For example, prior analysis of the Boston Healthy Public Housing Initiative (HPHI), a longitudinal single-cohort community-based participatory research intervention study, revealed significant improvements in child’s symptoms and AQOL with some improvement prior to environmental interventions but increased improvement rates thereafter.10 Environmental interventions demonstrated significant reductions in cockroach allergens and other exposures, corresponding to the time window of greatest health improvement.11 Although health improvements did not differ by allergy status, despite the interventions’ focus on allergen reduction, they were modified by social factors (e.g., fear of violence). Together, these results suggest that social factors influenced child AQOL improvements and intervention efficacy. Expanding on this work to consider possible ancillary benefits to caregivers, Figure 1 depicts multiple social and physical aspects of the environmental intervention study which may influence caregiver AQOL.

In this study, we use HPHI data to explore the multiple pathways proposed in Figure 1. We use intensive longitudinal data to examine caregiver AQOL trends. Caregiver AQOL improvements not temporally correlated with child AQOL improvements suggest the significance of other pathways. We hypothesize that:

Caregiver AQOL improves over the course of the study.

Caregiver AQOL is correlated with child AQOL.

Rates of caregiver AQOL improvements vary across phases of the study. Improvements prior to environmental interventions, if unexplained by child AQOL, may suggest direct effects of study-related social support or participation.

To better understand the child–caregiver AQOL relationship, we consider whether:

Caregiver perceived stress decreases over the course of study, directly improving caregiver AQOL and possibly mediating (explaining) part of the association between child and caregiver AQOL or between study-related participation or socials support and caregiver AQOL.

Social support increases over the course of study, directly improving caregiver AQOL and possibly modifying the effect of caregiver stress on caregiver AQOL.

Methods

Between April 2002 and January 2003, 78 asthmatic children aged 4 to 17 years were recruited from three public housing developments in Boston for a community-based participatory research study of indoor environmental interventions. In-home interventions focused on allergen reduction, which included mattress replacement, contracted cleaning, and integrated pest management. Recruitment efforts, enrollment criteria, and environmental interventions are detailed elsewhere.9,10 Of 78 enrollees, 58 children of 44 primary caregivers were retained through interventions. Forty-two children of 32 primary caregivers received interventions with both caregiver and child providing complete data for at least 3 months prior to and following interventions, allowing for longitudinal analyses wherein individuals serve as their own controls. No additional control group was included. Participants were enrolled and environmental interventions were performed in two study phases 6 months apart to disentangle effects of season and environmental interventions.

AQOL, social support, and perceived stress data were collected monthly for caregiver and child, providing temporal resolution for longitudinal analysis. We compare month-to-month AQOL improvements during multiple study phases: preintervention, short-term postenvironmental interventions (<5 months following), and longer-term postinterventions (≥5 months following). The 5-month cutpoint was derived previously,10 corresponding with maximum decline trends in home allergen levels following interventions,11 and an observed inflection point in average child AQOL trends.

Beyond direct environmental interventions, there were numerous interactions with study participants. Throughout the study, community health advocates (CHAs; residents of the developments or surrounding neighborhoods hired as study team members) visited the families’ home, met with caregivers, performed data collection, and provided general asthma-related support. A limited asthma education/case management effort was provided to all participants by a community health nurse prior to implementing environmental interventions, and some nurse contact continued throughout the study. This approach was designed to ensure that families had similar access to health care and basic asthma education, creating a roughly comparable baseline prior to environmental interventions. It was not designed as a formal social support or educational intervention, and few children changed medications during the study.9

Data Collection

Standardized health outcomes questionnaires were administered monthly by the CHA. Instruments included the Juniper Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaires for caregivers (hereafter referred to as AQLQ)12 and Juniper Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaires (hereafter, PAQLQ) for children.13 The AQLQ, a 13-item instrument, assesses caregiver activity limitation and emotional function related to their child’s asthma, not their own health (Appendix I). The PAQLQ, a 23-item questionnaire, evaluates the child’s AQOL in three domains: symptoms, activity limitation, and emotional function. Following the recommended protocol, older children responded directly, and caregivers responded for children under the age of 8 years. For both instruments, item responses range from 1 (worst) to 7 (best). The total AQLQ or PAQLQ, our key outcomes, are the average of each questionnaire’s subdomains.

Child PAQLQ and caregiver AQLQ are validated as evaluative (within-subject) and discriminative (between-subject) instruments. The AQLQ evaluative properties are of primary interest to our longitudinal study and have been previously validated to detect caregiver responses to changes in child’s symptoms with treatment and natural fluctuations (e.g., seasonality).12

Additional measures relevant to longitudinal analysis of caregiver AQLQ included an assessment of social support, which was measured monthly using a standardized five-item instrument adapted from Block.14 This Social Support Network Scale measures resources and sources of social support and has been validated in cohorts of lower-income urban minority women. This social support scale examines general sources of support (external to any support received in the context of this environmental intervention study) in caregivers’ lives (Appendix II). Responses range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), and scores for items in two domains (emotional, instrumental support) are averaged to a global mean score. Our internal consistency was high (α = 0.88) across all five social support items. Caregiver perceived stress was measured monthly using the four-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), shown to be a valid, reliable measure of the degree to which individuals appraise their current life situations as stressful.15

Analytic Methods

Using our conceptual framework (Figure 1), we developed longitudinal models to explore time trends and multiple pathways through which environmental intervention studies may improve caregiver AQOL. We were particularly interested in caregiver AQOL benefits that are unexplained by any improvements in the child’s AQOL, as well as in improvements prior to environmental interventions, when some of the pathways identified in Figure 1 (e.g., improved environmental conditions) would not be influential. Because the AQLQ was designed to capture caregiver responses to their child’s asthma, not to their own health, we expect strong caregiver AQLQ–child PAQLQ correlation, and final models include child’s PAQLQ and test additional predictors.

Mixed models were developed to examine trends in caregiver AQLQ and key predictors (child PAQLQ, social support, and perceived stress), overall and in multiple study phases. The longitudinal model depicting overall trends is:

|

1 |

where Yij is the child PAQLQ, caregiver AQLQ, social support, or perceived stress (continuous time-varying measures) for participant i at time j. Time is continuous in units of months, centered at initial environmental intervention (i.e., date of intensive cleaning).

The longitudinal model allowing for different slopes (rates of AQOL improvement) during different study periods is:

|

2 |

where Period is categorical (preintervention, <5 months after intervention, ≥5 months after intervention).

The longitudinal model for the influence of child PAQLQ, social support, and other factors on caregiver AQLQ is:

|

3 |

where Development is the housing development, Ethnicity is the self-reported race or ethnicity (Black/African American, Hispanic), and social support and PSS are the scales described above. All models include months (by study period), child PAQLQ, development, and race/ethnicity. Social support and perceived stress are added singly and in combination.

Models were run in Proc Mixed for SAS 9.1 with correction for temporally autocorrelated repeated within-subject measures (random intercepts and slopes by child). Errors are assumed normally distributed.

Sensitivity Analyses

Due to possible autocorrelation among mothers with multiple children in the study, we tested the effect of using random intercepts and slopes by caregiver, rather than by child. Because caregivers provided PAQLQ responses for children under 8 years old, we expected stronger correlations between AQLQ and PAQLQ for younger children, and thus compared Spearman correlations stratified by age and tested effects of age-adjustment in all models.

Because child’s recent asthma symptoms may influence caregiver worry and caregiving behaviors, we examined temporal lags between child PAQLQ and caregiver AQLQ. These mixed models tested prior-month and 2-months-prior child PAQLQ on caregiver AQLQ, adjusting for contemporaneous PAQLQ.

In addition, because caregiver asthma-related quality of life may influence child’s health through familial stress, attention, or caregiving, we tested prior-month caregiver AQLQ on child’s PAQLQ, adjusting for contemporaneous caregiver AQLQ. We also tested prior-month caregiver social support on caregiver AQLQ and child PAQLQ.

Our social support measure captures external support from family and friends, not support related to study participation. To consider possible study-related support, for which no formal questionnaire was available, we calculated the number of CHA visits the family had received at each questionnaire date to estimate the intensity of study interaction. We tested this term in place of the time-in-study variable (Timej) and in conjunction with it.

Finally, we considered whether participation in an allergen-reducing study may lead to cleaning behavior changes before environmental interventions were initiated. These effects are likely captured through adjustment for child’s PAQLQ, but could also influence caregivers’ perceptions of environmental quality or of child’s well-being. Thus, we tested a categorical home-cleanliness variable created during integrated pest management evaluations.

Results

We examined up to 13 months of caregiver AQLQ, perceived stress, and social support data for 32 caregivers to 42 children in three developments. We included 379 complete caregiver AQLQ questionnaires collected between 6 months before and 9 months following interventions. All primary caregivers were female, 78% were Hispanic, and 22% had more than one asthmatic child in the study (Table 1). Based on our inclusion criteria (at least 3 months’ data before and after interventions), all caregivers contributed information to the preterm and short-term (<5 months) postintervention phases and only four left the study 5 months following interventions and did not contribute information to the longer-term (≥5 months post) phase.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and questionnaire scores (quality of life, perceived stress, and social support) at enrollment for caregivers and children

| Caregivers | Children | |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) = 32 (100) | N (%) = 42 (100) | |

| Age: 8 years and older | – | 31 (74) |

| Sex: percent female | 32 (100) | 22 (52) |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||

| Hispanic | 25 (78) | 31 (74) |

| African American | 6 (19) | 10 (24) |

| Children with asthma enrolled in the study | ||

| One | 25 (78) | – |

| Two | 4 (13) | |

| Three | 3 (9) | |

| In-home smoking | 13 (41) | 19 (45) |

| Development | ||

| West Broadway | 17 (53) | 19 (45) |

| Franklin Hill | 10 (31) | 16 (38) |

| Washington Beech | 5 (16) | 7 (17) |

| Continuous variables, mean (SD) | ||

| Household size | 4.1 (1.9) | 4.4 (2.1) |

| Total AQLQ (PAQLQ) | 5.0 (1.7) | 4.9 (1.3) |

| Activity limitation | 4.7 (1.9) | 4.6 (1.4) |

| Emotional function | 5.0 (1.7) | 5.4 (1.3) |

| Symptoms | – | 4.8 (1.4) |

| Perceived stress scale | 2.8 (0.9) | – |

| Social Support scale | 4.0 (0.9) | – |

aDue to incomplete reporting, the race/ethnicity variable does not sum to 100%

Trends in Caregiver AQLQ, Child PAQLQ, Social Support, and Perceived Stress

We observed significant caregiver AQLQ improvements overall, averaging 0.08 points per month across all participants and study periods (p < 0.0001) (Table 2, model 1A). Caregiver AQLQ improved significantly prior to interventions (0.13 points per month, p = 0.0004) and within 5 months following interventions (0.11 points per month, p = 0.009) with reduced but still significant improvement rates more than 5 months postintervention (0.06 points per month, p = 0.002) (Table 2, model 1B). Mean caregiver AQLQ scores in each period likewise indicate positive trends; caregiver AQLQ averaged 5.3 (SD = 1.5) before interventions, 5.8 (SD = 1.6) in the 5 months following, and 6.2 (SD = 1.0) in later months.

Table 2.

Observed longitudinal trends in caregiver AQLQ, child PAQLQ, caregiver social support, and perceived stress

| Outcome | Model 1: caregiver AQLQ (n = 379) | Model 2: child PAQLQ (n = 344) | Model 3: social support (n = 405) | Model 4: perceived stress (n = 412) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | |

| Model A: assuming constant rate of change throughout study | ||||

| Intercept | 5.53 (0.22)* | 5.28 (0.18)* | 4.21 (0.13)* | 2.90 (0.05)* |

| Month | 0.08 (0.01)* | 0.06 (0.01)* | 0.004 (0.005) | −0.002 (0.008) |

| Model B: allowing for varying slopes during multiple periods | ||||

| Intercept | 5.62 (0.24)* | 5.16 (0.21)* | 4.28 (0.13)* | 2.81 (0.09)* |

| Month (preintervention) | 0.13 (0.04)* | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.033 (0.02) | −0.04 (0.03) |

| Month (<5 months post) | 0.11 (0.04)* | 0.19 (0.05)* | −0.014 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.03) |

| Month (≥5 months post) | 0.06 (0.01)* | 0.05 (0.02)* | −0.007 (0.008) | 0.01 (0.01) |

Models are not corrected for effects of development, race/ethnicity, or other confounders. Models are labeled by outcome variable and sample sizes refer to individuals with complete data included in each model

*p < 0.05, related to the difference of the slope from zero in each study period

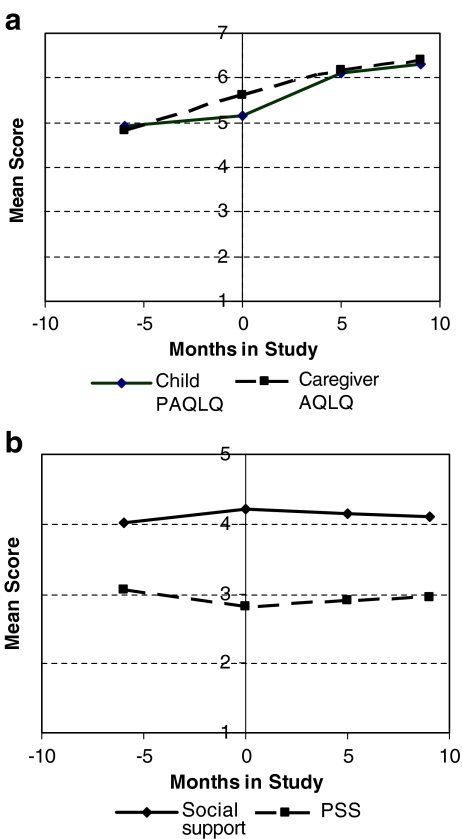

In contrast, these children demonstrated no significant PAQLQ improvements before interventions (0.04 points per month, p = 0.34), significant improvements in the 5 months following (0.19 points per month, p < 0.0001), and reduced but still significant improvements in later months (0.05 points per month, p = 0.02) (Table 2, model 2B). Trends in asthma symptoms, a PAQLQ subscale, were very similar to total child PAQLQ trends.

We observed no significant trends in caregiver social support or perceived stress over the study (Table 2, models 3A and 4A). Longitudinal analyses, however, rely on individual’s trends, which varied substantially across caregivers with some indications of social support increases (p = 0.08) (Table 2, model 3B) and perceived stress decreases (p = 0.16) before interventions (Table 2, model 4B).

Associations Between Child PAQLQ and Caregiver AQLQ

Child PAQLQ and caregiver AQLQ were significantly correlated (Spearman r = 0.56, p < 0.0001), although caregivers improved most before interventions and children improved most in the 5 months following (Figure 2a and Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Observed trends for caregiver and child over the course of study (mean rate of increase per period). a Trends in caregiver AQLQ and child PAQLQ scores. b Trends in caregiver social support and perceived stress.

Including contemporaneous child PAQLQ in models predicting caregiver AQLQ supports these patterns (Table 3). After adjusting for development and race/ethnicity, a one-point higher child PAQLQ overall predicts a 0.17-point higher caregiver AQLQ (p = 0.0005). Adding child PAQLQ to the longitudinal model for caregiver AQLQ, slopes in the postintervention period are reduced (from 0.11 to 0.07 points per month within 5 months, from 0.06 to 0.04 points per month later) with no change in preintervention slopes (Table 3, model 2).

Table 3.

Models predicting longitudinal trends in caregiver AQLQ over time, as a function of child PAQLQ, social support, and perceived stress

| Model 1: null (n = 379) | Model 2: child PAQLQ (n = 315) | Model 3: child PAQLQ and social support (n = 312) | Model 4: child PAQLQ and perceived stress (n = 314) | Model 5: child PAQLQ, perceived stress, and social support (n = 311) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | |

| Intercept | 6.16 (1.22)* | 5.20 (1.20)* | 4.95 (1.25)* | 5.81 (1.25)* | 5.55 (1.29)* |

| Month (preintervention) | 0.13 (0.04)* | 0.13 (0.04)* | 0.13 (0.04)* | 0.13 (0.04)* | 0.13 (0.04)* |

| Month (<5 months post) | 0.11 (0.04)* | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.04) |

| Month (>5 months post) | 0.06 (0.02)* | 0.04 (0.02)* | 0.04 (0.02)* | 0.04 (0.02)* | 0.04 (0.02)* |

| Child PAQLQ | – | 0.17 (0.05)* | 0.17 (0.05)* | 0.16 (0.05)* | 0.16 (0.05)* |

| Social support | – | – | 0.10 (0.12) | – | 0.10 (0.12) |

| Perceived stress | – | – | – | −0.17 (0.07)* | −0.17 (0.07)* |

All models were corrected for effects of development and race/ethnicity (results for these covariates not shown). Models are labeled by predictors included

*p < 0.05

Social Support as a Predictor of Caregiver AQLQ

To examine the influence of general social support on caregiver AQLQ, after correcting for child PAQLQ, we added social support to the model (Table 3, model 3). Comparing these results to model 2, we see that the time trends are maintained; general social support does not significantly predict caregiver AQLQ or influence the effects of other covariates. Removing child PAQLQ from model 3 (not shown) reveals the same caregiver AQLQ trends and a nonsignificant positive effect of general social support on caregiver AQLQ (β = 0.15, p = 0.14). Thus, the aspects of social support captured (nonstudy-related) by our measure do not account for caregiver AQLQ trends and do not modify the influence of child PAQLQ on caregiver AQLQ.

Perceived Stress as a Predictor of Caregiver PAQLQ

Child PAQLQ may influence caregiver AQLQ through reduced caregiving demand and stress. In addition, reduced stress, a possible result of participation and support, may directly improve caregiver AQLQ, even if our social support measure does not accurately capture this benefit. We tested these effects by monthly perceived stress (PSS) to the model, examining its effect estimate and resultant changes in the observed child PAQLQ–caregiver AQLQ association (Table 3, model 4 vs. model 2) and the observed trend in caregiver AQLQ. A one-unit increase in PSS predicted a 0.17-point decrease in caregiver AQLQ (p = 0.02) overall, but inclusion of PSS in the model did not alter observed effects of social support (Table 3, model 5 vs. model 3), child PAQLQ, or time trends in caregiver AQLQ. As such, stress significantly predicts caregiver AQLQ directly, but not primarily as a mediator for the effects of child PAQLQ or measured social support. Stress does decrease in the preintervention phase, however, contemporaneously with AQLQ.

Social Support as a Modifier of the Stress–AQLQ Relationship

Finally, we considered whether general social support influences caregiver AQLQ indirectly by reducing (buffering) the observed effect of stress (Figure 1). We tested this hypothesis in two ways: (1) comparing models for the effect of stress on caregiver AQLQ, with and without social support, to observe any reduction in the social support coefficient and (2) testing a stress–social support interaction term on caregiver AQLQ.

The model for the combined effects of stress and general social support on caregiver AQLQ (Table 3, model 5) indicates that stress, but not social support, influences caregiver AQLQ. The influence of stress on caregiver AQLQ is unchanged by adjusting for general social support. The stress–social support interaction term was not significant (results not shown), using either continuous or binary measures of social support and stress. In all cases, stress significantly predicted caregiver AQLQ, general social support did not, and the interaction was not significant. Thus, general social support, as measured in this study, did not buffer the stress–AQLQ association.

Sensitivity Analyses

Autocorrelation due to Caregivers with Multiple Children in the Study

We tested models with random intercepts and slopes by caregiver (rather than by child), producing comparable results.

Bias due to Caregivers’ Report of Child’s PAQLQ for Children Under 8 Years

As hypothesized, Spearman correlations between caregiver AQLQ and child PAQLQ were higher for children under 8 years old (r = 0.61) than for older children (r = 0.42). Adjusting for child’s age, however, produced the same trends and effects of child PAQLQ on caregiver AQLQ, indicating no influential age-related biases. There was an independent effect of child’s age, however; caregivers to children under 8 years old averaged 1.2-point higher AQLQ scores.

Lag Effects Between Child PAQLQ and Caregiver AQLQ

Mixed models indicate significant associations between prior-month child PAQLQ and caregiver AQLQ (β = 0.10, p = 0.04), adjusted for same-month child PAQLQ. Prior-month child PAQLQ, however, did not maintain significance in longitudinal models or alter the effect of same-month child PAQLQ.

Because caregiver AQLQ may influence child’s health through familial stress, attention, or caregiving practices, we tested whether prior-month caregiver AQLQ predicted child’s PAQLQ, adjusting for same-month caregiver AQLQ, and found no significant effect. Prior-month general social support did not predict caregiver AQLQ. Prior-month stress was nonsignificant after adjusting for same-month stress, child’s PAQLQ, development, and race/ethnicity (β = −0.11; p = 0.12).

Contact with CHA as a Time-Varying Predictor of Caregiver AQLQ

To test whether caregiver AQLQ improves with more CHA contact, we replaced the time-in-study variable in longitudinal models with the corresponding CHA visit number, but found no significant effect on caregiver AQLQ. In mixed models allowing for separate influences of time-in-study and CHA visit number on caregiver AQLQ, only time-in-study retained significance.

Preintervention Behavioral Changes

Finally, we tested a categorical home-cleanliness variable created during integrated pest management evaluations to assess preintervention cleaning behavior changes, which did not alter the effects of child PAQLQ on caregiver AQLQ or explain caregiver AQLQ improvements.

Discussion

Our findings indicate significant improvements in caregiver’s quality of life related to their child’s asthma (AQOL) over the course of our study, indicating significant ancillary benefits to caregivers from an environmental intervention study aimed at alleviating children’s asthma. While the caregiver and child AQOL measures were highly correlated, they followed somewhat different time trends, providing some insight about potential causal factors. In this analysis, children’s greatest AQOL improvements occurred within 5 months following interventions. In contrast, for caregivers, the greatest AQOL improvements occurred before environmental interventions. Preintervention caregiver AQOL improvements were not explained by child’s AQOL, perceived stress, or general social support, although child’s AQOL did explain some caregiver AQOL improvements following interventions, and lower caregiver stress was associated with improved caregiver AQOL.

For caregivers, clear preintervention improvements suggest effects of study-related participation or psychosocial benefits (e.g., support from CHAs, perceptions of needs being addressed), although our general social support measure did not predict caregiver AQOL in any period. This measure was, however, unlikely to capture study participation effects, as it identifies broad emotional and instrumental support sources in caregivers’ lives unrelated to the study itself. The number of CHA visits also did not predict caregiver AQLQ, but may poorly proxy for support, as little variability remained after restricting our cohort to caregivers with three or more preintervention and postintervention questionnaires, and the nature of the CHA–caregiver relationship was never formally assessed. Our sample size was inadequate to evaluate between-CHA differences in support, but anecdotal field data indicate that the nature and quality of interactions varied.

Though our study was not designed as a formal social support intervention, we recognize that asthma-related support and ongoing contact with caregivers inherent to efforts to improve in-home environmental conditions can be a significant influence on caregivers’ lives, especially in underserved communities. As such, future environmental intervention studies may benefit from more formal evaluations of the social support they provide over time, drawing from the wide literature on social support interventions, wherein multiple health and behavioral benefits have been documented,16 including improved QOL in cancer survivors,17,18 cardiovascular patients,19 and long-term caregivers.20–22 The varying nature of support interventions has led to inconsistent, though largely positive, efficacy evaluations.23 Although the active ingredient of support interventions remains unidentified, it may be related to enhanced structural and functional characteristics (e.g., denser or more specific networks or richer support received), improved coping skills, and stress reduction that are provided by these interventions.24

We also examined caregiver perceived stress, considering several possible pathways through which it may influence caregiver AQOL; lower stress may directly improve AQOL or, alternatively, stress may mediate the effect of social support or child AQOL on caregiver AQOL. We found that higher monthly caregiver perceived stress conferred reduced caregiver AQOL, although stress was not a significant mediator of the effect of child AQOL or social support on caregiver AQOL. The role of perceived stress in shaping AQOL remains significant, and better understanding its role in shaping caregiver well-being clearly deserves greater attention. In addition, psychosocial aspects of environmental interventions, including reduced caregiver stress, should be considered in future studies.

Our findings demonstrated significant ancillary benefits for caregivers with regard to their asthma-related quality of life and provided insight about differential trends between caregiver and child outcomes. There are, however, some limitations to our analysis. First, HPHI was designed to understand health benefits of physical environmental interventions for asthmatic children, and as such, several useful measures for social epidemiological analysis were not collected. Development of instruments appropriate to assessing the auxiliary support-related aspects of environmental intervention studies, including the nature of CHA–caregiver relationships, would be extremely valuable for future studies. Measures of caregiver negative affect and depression would be beneficial,25 particularly where caregivers report for themselves and their children. This covariance was accounted for, in part, by using a perceived stress measure; the significance of this term on caregiver AQLQ indicates a need to consider other measures of negative affect.

Our small sample size is clearly a limitation, as is the lack of a control population. Our time-intensive longitudinal data, however, did provide adequate statistical power, allowing individuals to serve as their own controls, though the small number of caregivers limited power for examining nontime-varying covariates (e.g., child’s age). Our findings were somewhat sensitive to exclusion criteria; the findings for child PAQLQ in Table 2 differ from our prior analysis of 51 children, which revealed near-significant child PAQLQ improvements before interventions (0.09 points per month, p = 0.07) which continued afterwards (0.16 points per month, p = 0.39 for change in slopes).10 The current analysis was limited to caregivers providing three preintervention questionnaires, and thus may be a different subset of participants or a more robust estimate given a greater number of longitudinal measures. The lack of a control population is clearly a limitation in any intervention study, especially with numerous interventions; in this study, the community-based participatory research nature of our study significantly influenced study design as community partners determined that offering interventions to only some participants was not appropriate.9 As such, we rely on time-intensive data collection and longitudinal analyses. While some observed improvements represent regression toward the mean or are not attributable to our interventions, our qualitative conclusion that caregiver AQLQ is affected by multiple factors beyond child PAQLQ is robust to these concerns. More generally, our findings emphasize the value of longitudinal methods, both to address the lack of a control population and to capture the differences in time trends between child and caregiver AQOL.

Despite these limitations, our study provides some useful insights. First, in a longitudinal environmental intervention study focused on children, we showed significant ancillary benefits to caregivers which should be more explicitly considered and directly measured in future studies and may increase the value of intervention efforts. It remains a challenge to distinguish caregiver improvements resulting from child’s AQOL from those representing the child and caregiver’s independent response to the same phenomenon (i.e., participation, perceived environmental improvements); as such, the precise reason for strong preintervention caregiver improvements remains unresolved. The framework we introduced could allow more detailed exploration of causal pathways for caregiver or child QOL improvements in future studies, which would benefit from richer assessment of social context and participation-related support. In addition, we demonstrate social aspects of environmental interventions (e.g., reduced stress, social support) which may contribute equally toward health improvements and should be considered and quantified in conjunction with physical environmental improvements. To better understand these social aspects of environmental intervention studies, we recommend the development of scales to measure study-related social support and perceived benefits. Such measures may enable future studies to distinguish important social and psychosocial influences of interventions (e.g., participation, having needs met, social support, perceived benefit) from their physical environmental attributes.

Acknowledgements

The Healthy Public Housing Initiative was funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Office of Healthy Homes and Lead Hazard Control (grant no. MALHH0077-00), as well as grants from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, the Boston Foundation, and the Jessie B. Cox Charitable Trust. Additional support was provided by the Ford Foundation, the Akira Yamaguchi Endowment, and American Lung Association. Partners include the Boston Housing Authority and the Boston Public Health Commission (BPHC); the Committee for Boston Public Housing (CBPH), the West Broadway Tenant Task Force and the Franklin Hill Tenant Task Force; Boston’s three schools of public health at Boston University, Harvard University, and Tufts University; and Peregrine Energy and Urban Habitat Initiatives.

Appendix I: Pediatric Asthma Caregiver’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ)

During the past week, how often:

(1 = all of the time, 7 = none of the time)

Did you feel helpless or frightened when your child experienced cough, wheeze, or breathlessness?

Did your family need to change plans because of your child’s asthma?

Did you feel frustrated or impatient because your child was irritable due to asthma?

Did your child’s asthma interfere with your job or work around the house?

Did you feel upset because of your child’s cough, wheeze, or breathlessness?

Did you have sleepless nights because of your child’s asthma?

Were you bothered because your child’s asthma interfered with family relationships?

Were you awakened during the night because of your child’s asthma?

Did you feel angry that your child has asthma?

During the past week, how worried or concerned were you:

(1 = very, very worried/concerned, 7 = not worried/concerned)

About your child’s performance of normal daily activities?

About your child’s asthma medications and side effects?

About being overprotective of your child?

About your child being able to lead a normal life?

Appendix II: Social Support Network Scale, adapted from Block et al. (2000)

How strongly do you agree with each of the following:

(1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree)

(Emotional support items):

Someone I’m close to makes me feel confident in myself.

Someone I care about stands by me through good times and bad times.

There is someone I can talk to openly about anything.

(Instrumental support items):

I have someone to stay with or leave my kids with in an emergency.

I have someone to borrow money from in an emergency.

References

- 1.Timmermans S, Freidin B. Caretaking as articulation work: the effects of taking up responsibility for a child with asthma on labor force participation. Soc Sci Med. 2007. 65(7):1351–1163. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Morgan WJ, Crain EF, Gruchalla RS, et al. Results of a home-based environmental intervention among urban children with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2004. 351(11):1068–1080. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa032097. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Evans R 3rd, Gergen PJ, Mitchell H, et al. A randomized clinical trial to reduce asthma morbidity among inner-city children: results of the National Cooperative Inner-City Asthma Study. J Pediatr. 1999. 135(3):332–338. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(99)70130-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.McDonald E, Cook D, Newman T, et al. Effect of air filtration systems on asthma: a systematic review of randomized trials. Chest. 2002. 122(5):1535–1542. doi:10.1378/chest.122.5.1535. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Custovic A, Simpson BM, Simpson A, et al. Effect of environmental manipulation on pregnancy and early life on respiratory symptoms and atopy during the first year of life: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2001. 358:188–193. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05406-X. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Krieger JW, Takaro TK, Song L, et al. The Seattle-King County Healthy Homes Project: a randomized, controlled trial of a community health worker intervention to decrease exposure to indoor asthma triggers. Am J Public Health. 2005. 95(4):652–659. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.042994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.NHLBI. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2007.

- 8.Krieger J, Allen C, Cheadle A. Using community-base participatory research to address social determinants of health: lessons learned from Seattle Partners for Healthy Communities. Health Educ Behav. 2002. 29:361–382. doi:10.1177/109019810202900307. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Levy J, Brugge D, Peters J, et al. A community-based participatory research study of multifaceted in-home environmental interventions for pediatric asthmatics in public housing. Soc Sci Med. 2006. 63:2191–2203. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Clougherty JE, Levy JI, Hynes HP, et al. A longitudinal analysis of the efficacy of environmental interventions on asthma-related quality of life and symptoms among children in urban public housing. J Asthma. 2006. 43:335–343. doi:10.1080/02770900600701408. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Peters J, Levy J, Muilenberg M, et al. Efficacy of integrated pest management in reducing cockroach allergen concentrations in urban public housing. J Asthma. 2007. 44:455–460. doi:10.1080/02770900701421971. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, et al. Measuring quality of life in the parents of children with asthma. Qual Life Res. 1996. 5:27–34. doi:10.1007/BF00435966. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, et al. Measuring quality of life in children with asthma. Qual Life Res. 1996. 5:35–46. doi:10.1007/BF00435967. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Block C. The Chicago Women’s Health Risk Study: Risk Of Serious Injury or Death in Intimate Violence. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2000.

- 15.Cohen S, Kamarack T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983. 24(4):385–396. doi:10.2307/2136404. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Berkman L, Glass T. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In: Berkman L, Kawachi I, eds. Social Epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000.

- 17.Henoch I, Bergman B, Gustafsson M, et al. The impact of symptoms, coping capacity, and social support on quality of life experience over time in patients with lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(4):370–379. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Bloom J, Petersen D, Kang S. Multi-dimensional quality of life among long-term (5+ years) adult cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2007. 16(8):691–706. doi:10.1002/pon.1208. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Scherer M, Stanske B, Wetzel D, et al. Disease-specific quality of life in primary care patients with heart failure. Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitatssich. 2007;101(3):185–190. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Smerglia V, Miller N, Sotnak D, et al. Social support and adjustment to caring for elder family members: a multi-study analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2007. 11(2):205–217. doi:10.1080/13607860600844515. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Shu B, Lung F. The effect of support group on the mental health and quality of life for mothers with autistic children. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2005;49(Pt 1):47–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Walsh K, Jones L, Tookman A, et al. Reducing emotional distress in people caring for patients receiving specialist palliative care. Randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2007. 190:142–147. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.023960. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Hogan B, Linden W, Najarian B. Social support interventions: do they work? Clin Psychol Rev. 2002. 22:381–440. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Schradle S, Dougher M. Social support as a mediator of stress: theoretical and empirical issues. Clin Psychol Rev. 1985. 5:641–661. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(85)90039-X. [DOI]

- 25.Price M, Bratton D, Klinnert M. Caregiver negative affect is a primary determinant of caregiver report of pediatric asthma quality of life. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89(6):540–541. [DOI] [PubMed]