Abstract

Mammals are metagenomic in that they are composed not only of their own gene complements but also those of all of their associated microbes. To understand the co-evolution of the mammals and their indigenous microbial communities, we conducted a network-based analysis of bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences from the fecal microbiota of humans and 59 other mammalian species living in two zoos and the wild. The results indicate that host diet and phylogeny both influence bacterial diversity, which increases from carnivory to omnivory to herbivory, that bacterial communities co-diversified with their hosts, and that the gut microbiota of humans living a modern lifestyle is typical of omnivorous primates.

Our ‘metagenome’ is a composite of Homo sapiens genes and genes present in the genomes of the trillions of microbes that colonize our adult bodies (1). The vast majority of these microbes live in our distal guts. ‘Our’ microbial genomes (microbiome) encode metabolic functions that we have not had to evolve wholly on our own, including the ability to extract energy and nutrients from our diet. It is unclear how distinctively human our gut microbiota is, or how modern H. sapiens’ ability to construct a wide range of diets has affected our gut microbial ecology. In this study we address two general questions concerning the evolution of mammals: how do diet and host phylogeny shape mammalian microbiota? When a mammalian species acquires a new dietary niche, how does its gut microbiota relate to the microbiota of its close relatives?

The acquisition of a new diet is a fundamental driver for the evolution of new species. Co-evolution, the reciprocal adaptations occurring between interacting species (2), produces dramatic physiological changes that are often recorded in fossil remains. For instance, although mammals made their first appearance on the world stage in the Jurassic (~160 Ma), most modern species arose during the Quaternary (1.8 Ma to present (5)), when C4-grasslands expanded in response to a fall in atmospheric CO2 levels and/or climate changes (6–8). The switch to a C4 plant-dominated diet selected for herbivores with high-crowned teeth (3) and longer gut retention times necessary for the digestion of lower-quality forage (9). However, these adaptations may not suffice for the exploitation of a new dietary niche. The community of microbes in the gut constitutes a potentially critical yet unexplored component of diet-driven speciation.

Because we cannot interrogate extinct gut microbiotas directly, past evolutionary processes can only be inferred from comparative analyses of extant mammalian gut microbial communities. Therefore, we have analyzed the fecal microbial communities of 106 individual mammals representing 60 species from 13 taxonomic orders, including 17 non-human primates. To isolate the effects of phylogeny and diet, we included multiple samples from many of the mammalian species, as well as species that had unusual diets compared to their close phylogenetic relatives. For example, the majority of the non-human primate species studied were omnivores (12 of 17), but the leaf-eating (folivorous) East Angolan Colobus, Eastern Black and White Colobus, Douc Langur and François Langur were also sampled. In addition, the herbivorous Giant Panda and Red Panda were included from the Carnivora. Most animals were housed at the San Diego Zoo and the San Diego Zoo’s Wild Animal Park (n=15) or the St Louis Zoo (n=56). Others were examined in the wild (n=29) or domesticated (n=6; Table S1). To test the reproducibility of host species-associated gut microbiotas, and to gauge the effects of animal provenance, mammalian species were represented by multiple individuals from multiple locales where possible, and wild animals were chosen to match captive animals. We generated a dataset of >20,000 16S rRNA gene sequences; to compare the human, primate and non-primate mammalian gut microbiotas, the 106 samples also included published fecal bacterial 16S rRNA sequences (>3,000) from wild African Gorilla (12), Holstein cattle (13), Wistar rats (14), and healthy humans of both sexes, ranging in age from 27 to 94, living on 3 continents and including a strict vegetarian (10,15–18; Table S1).

We used network-based analyses to map gut microbial community composition and structure onto mammalian phylogeny and diet, thereby complementing phylogeny-based microbial community comparisons. These analyses were used to bin 16S rRNA gene sequences into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and to display microbial genera partitioning across hosts. Genus-level OTUs (sets of sequences with ≥96% identity) and animal hosts were designated as nodes in a bipartite network, in which OTUs are connected to the hosts in which their sequences were found (Figure 1A). To cluster the OTUs and hosts in this network, we used the stochastic spring-embedded algorithm, as implemented in Cytoscape 2.5.2 (19), where nodes act like physical objects that repel each other, and connections act as a spring with a spring constant and a resting length; the nodes are organized in a way that minimizes forces in the network.

Figure 1. Network-based analyses of fecal bacterial communities in 60 mammalian species.

(A) Simplified cartoon illustration of a host-gut microbe network. Network diagrams are color-coded by (B) diet, (C) animal taxonomy, (D) animal provenance, or represent randomized assignments of OTUs to animal nodes (E). Abbreviations used for animal species (* indicates wild): Asian Elephants, ElephAs1–3; Baboons, Baboon, BaboonW; African Elephants, ElephAf1–4; Bwindi Gorilla, GorillaW; Hartmann’s Mountain Zebra, ZebraW; Armadillo, Arma; Argali Sheep, SheepA1–3; Babirusa, Barb; Seba’s Short tailed Bat, Bat; American Black Bears, BrBear1,2; Bush Dogs, BshDog1,3; Banteng, Banteng; Bighorn Sheep, SheepBH1–3; Black Lemur, BlLemur; Bonobo, Bonobo; Calimicos (Goeldi’s Marmoset), Calimico; Capybara, Capybara; Cheetahs, Cheet2,3; Chimpanzees, Chimp1,12; Eastern Black and White Colobus, BWColob; East Angolan Colobus, BWColobSD; Cattle, Cow1–3; Douc Langur, DcLangur; Echidna, Echidna; Flying Fox, FlyFox; François Langur, FrLangur; Giraffe, Giraffe; Western Lowland Gorillas, Gorilla, GorillaSD; Giant Panda, GtPanda; Geoffrey’s Marmoset, Marmoset; Grevy’s Zebra, GZebra; Humans, HumAdB, HumAdO, HumAdS, HumEckA, HumEckB, HumEckC, HumNag6, HumOldA, HumOldB, HumOldC, HumSuau, HumVeg; HumLC1A, HumLC1B, HumLC2A, HumLC2B; Hedgehog, HgHog; Horses, HorseJ, HorseM; Rock Hyraxes, Hyrax, HyraxSD; Spotted Hyenas, Hyena1,2; Indian Rhinoceros, InRhino; Red Kangaroos, KRoo1,2; Lions, Lion1–3; Mongoose Lemur, MgLemur; Naked Mole rat, Mole rat; Okapi, Okapi1–3; Orangutans, Orang1,2; Polar Bears, PBear1,2; Rabbit, Rabbit; Norway Rat (Wistar), Rat; Black Rhinoceros, BlRhino; Red Pandas, RdPanda, RdPandaSD; Red River Hog, RRHog; Ring Tailed Lemur, RtLemur; White-Faced Saki, Saki; Springboks, SpBok and SpBokSD; Spectacled Bear, SpecBear; Speke’s Gazelles, SpkGaz2,3; Prevost’s Squirrel, Squirrel; Spider Monkey, SpiMonk; Takin, Takin; Transcaspian Urial Sheep, SheepTU1,2; Visayun Warty Pig, VWPig; Somali Wild Ass, WildAss. See Table S1 for additional details.

The ensemble of sequences in this study provides an overarching view of the mammal gut microbiota. We detected members of 17 phyla (divisions) of Bacteria (11). The majority of sequences belong to the Firmicutes (65.7% of 19,548 classified sequences; 11) and to the Bacteroidetes (16.3%) - phyla previously shown to comprise the majority of sampled human (and mouse) gut-associated phylotypes (10,20). The other phyla represented were the Proteobacteria (8.8% of all sequences collected; 85% in the Gamma subdivision); Actinobacteria (4.7%); Verrucomicrobia (2.2%); Fusobacteria (0.67%); Spirochaetes, (0.46%); DSS1 (0.35%); Fibrobacteres (0.13%); TM7 (0.13%); deep-rooting Cyanobacteria (0.10%; these are not chloroplasts (21)); Planctomycetes (0.08%); Deferribacteres (0.05%); Lentisphaerae (0.04%); plus Chloroflexi, SR1, and Deinoccus-Thermus (all 0.005%). 1,985 16S rRNA gene sequences that passed a chimera-checking algorithm (21) could not be assigned to known phyla, based on BLAST searches against the Greengenes database (22) and the RDP taxonomy annotations (23). Of the phyla that were detected, only Firmicutes were found in all samples (Figure S1). However, each mammalian host harbored OTUs (96% ID) not observed in any other (at this level of sampling, on average, 56% and 62% of OTUs were unique within a sample and species, respectively; Table S1).

The network-based analyses disclosed that overall, the fecal microbial communities of same-species (conspecific) hosts were more similar to each other than to those of different host species: host nodes were significantly more connected within than between species (G-test for independence, G=11.9, P=0.0005; Figure 1B). Figure S2 presents a tree-based analysis where similarity is defined using the UniFrac metric. This metric is based on the degree to which individual communities share branch length on a common (master) phylogenetic tree constructed from all 16S rRNA sequences from all communities being compared (24,25). The results are consistent with the network-based analysis, i.e. they show that UniFrac distances are smaller within conspecific hosts than between non-conspecific hosts (P<0.005 by 1-tailed t-test, confirmed by matrix permutation and corrected for multiple comparisons).

The impact of host species on community composition is most evident when considering conspecific hosts living separately, since co-housing may confound any species effect. For example, the two Hamadryas Baboons cluster together (Figure S2), although one is from Namibia and the other from the St. Louis Zoo; similarly, the Red Pandas housed in different zoos cluster together. All 16 human samples also clustered together. Nevertheless, some conspecifics with different origins did not cluster (e.g., the two Western Lowland Gorillas), suggesting that diet and other environmental exposures (‘legacy effects’; 26) play roles in addition to host phylogeny (taxonomic order).

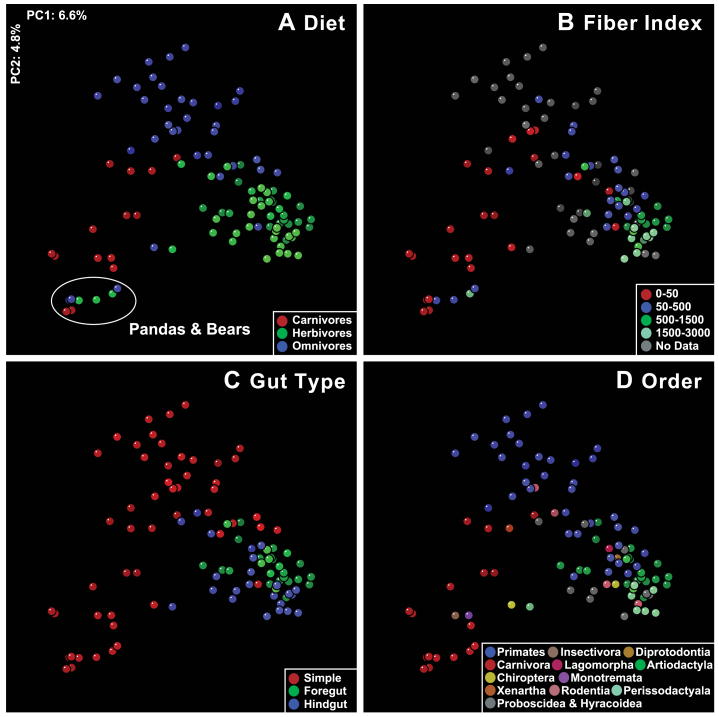

The clustering by diet (herbivore, omnivore, and carnivore) was highly significant in both the tree-based (Figure S2) and network-based analyses (Figure 1B). In the network-based analysis, host nodes are significantly more connected to other host nodes from the same diet group (G=115.8; P=5.1×10−27; 11). Similarly, hosts within the same taxonomic order are more connected in the network to hosts within the same order (Figure 1C; G=356; P=2.1×10−79). Likewise, UniFrac-based principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) showed clustering by diet (Figure 2A,B) and by taxonomic order (Figure 2D). (UniFrac distances are smaller for within versus between diet categories, and for within versus between orders, P<0.005). There was no significant clustering according to the provenance of the animals (including humans) in either the network- or UniFrac-based analyses (P>0.05 for both; Figures 1D and S2, respectively), or in a randomized network (Figure 1E)

Figure 2. Mammalian fecal bacterial communities clustered using principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of the UniFrac metric matrix.

PC1 and PC2 are plotted on x- and y-axes. Each circle corresponds to a fecal sample colored according to (A) diet, (B), diet fiber index, (C), gut morphology/physiology and (D) host taxonomic order. The percentage of the variation explained by the plotted principal coordinates is indicated on the axes.

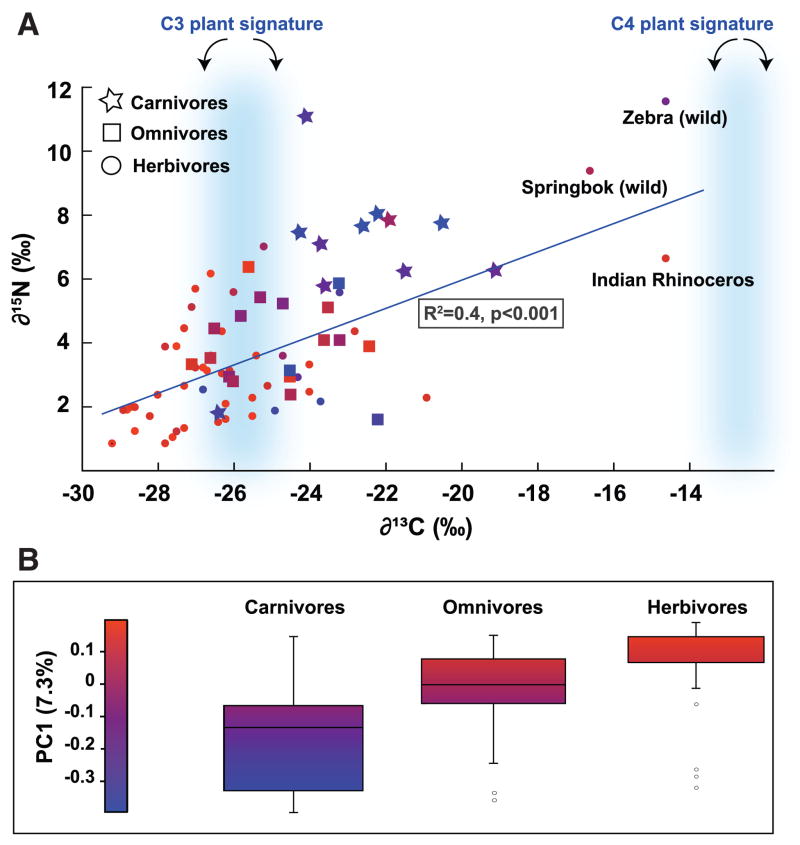

Classification of the mammals into herbivore, omnivore and carnivore groups was based on diet records and natural history. Heavy isotopes of carbon and nitrogen bio-accumulate in the food chain (27). Therefore, to obtain a more objective marker of diet, we measured stable isotope ratios of carbon and nitrogen in the feces (δ13C and δ15N, where δ (‰) = 1000*[(Rsample −Rstandard)/Rstandard) and R = ratio of atom percentages 13C/12C and 15N/14N). The results are consistent with the original diet group classification. Heavy isotopes were enriched in the order Herbivore < Omnivore < Carnivore (Figure 3A). The protein and fat content of the diets of animals in captivity (obtained from diet records) were positively correlated with δ13C and δ15N fecal values (R2 values for fat versus δ13C and δ15N were 0.51 and 0.45, respectively, and for protein, 0.36 and 0.38).

Figure 3. Markers of trophic level mapped onto the variance in fecal microbial community diversity.

(A) Stable isotope values for C and N plotted for each fecal sample, presented according to diet group. Symbols are colored according to their PC1 value: PC1 is the first principal coordinate of the PCoA of the unweighted UniFrac metric. δ13C ranges for C3 and C4 plants are highlighted in blue. R2 is for δ13C versus δ15N. (B) Box plots are shown for the three diet groups (central line is the mean; box outline equals 1 S.D.; the bar denotes 2 S.D.; circles are outliers). The majority of fecal δ13C values are intermediate between the average for C4 plants (−12.5%) and C3 plants (−26.7%).

To test for a direct link between diet and microbial community composition, stable isotope values were mapped onto the coordinates that explained the largest proportion of the variance in the microbial communities as determined by PCoA of the UniFrac distances between hosts (Figure 3B). Principal coordinate 1 (PC1) separates carnivores from herbivores and omnivores (mean is significantly lower for carnivores than herbivores, which are equivalent to omnivores, F80,2=9.9, p<0.001), and also correlated with δ13C and δ15N values (multiple regression R2= 0.25, F80,2=12.7, p<0.001). Together, these results support an association between microbial community membership and diet, and provide an independent validation of the dietary clustering observed in the network diagrams that is free of bias in assigning hosts to one of the three diet categories.

Underlying the correlation between bacterial community composition and diet is the partitioning of bacterial phyla among hosts according to diet. Herbivore microbiotas contained the most phyla (fourteen), carnivores contained the least (six), and omnivores were intermediate (twelve) (Figure S1). Phylogenetic trees constructed from 16S rRNA sequences from the feces of herbivores also had the greatest amount of total branch length (PD, phylogenetic diversity; panel A, Figure S3). Consistent with this finding, herbivores had the highest genus-level richness, followed by omnivores and carnivores (panel B, Figure S3).

Ancestral mammals were carnivores (9). We tested whether bacterial lineages found in herbivores were derived from lineages found in carnivores using an analysis based on the Fitch parsimony algorithm (11). The results do not support this notion, suggesting that gut bacterial communities required to live largely on a plant-based diet were likely acquired independently from the environment.

Adaptation to a plant-based diet was an evolutionary breakthrough in mammals that resulted in massive radiations: 80% of extant mammals are herbivores, and herbivory is present in most mammalian lineages (9). To access the more complex carbohydrates present in plants, such as celluloses and resistant starches, disparate mammalian lineages lengthened gut retention times to accommodate bacterial fermentation: this occurred via enlargement of the foregut or hindgut (9). We found that herbivores clustered into two groups that corresponded generally to foregut fermenters and hindgut fermenters: the foregut-fermenting Sheep, Kangaroo, Okapi, Giraffe and Cattle cluster together to form Herbivore Group 1 in Figure S2, while the hindgut-fermenting Elephant, Horse, Rhinoceros, Capybara, Mole rat and Gorilla cluster together in Herbivore Group 2. The strong impact of gut morphology on bacterial community composition is also evident in PCoA of the UniFrac data: herbivores separate into fore- and hindgut groups, and omnivores separate into hindgut fermenters and those with simple guts (Figure 2C,D).

Differences between the fecal communities of foregut and hindgut fermenters are likely due to host digestive physiology: in foregut fermenters, the digesta is moved into the equivalent of the monogastric stomach after fermentation, so that part of the microbiota is also digested; in hindgut fermenters, the fermentative microbes are more likely to be excreted in the feces. Fermentation requires microbial interactions such as cross-feeding and inter-species hydrogen transfer (28). Our results suggest that as mammals underwent convergent evolution in the morphological adaptations of their guts to herbivory, their microbiota arrived at similar compositional configurations in unrelated hosts with similar gut structures.

The diet outliers in our study were folivores. Despite their herbivorous diet, Red and Giant Pandas have simple guts, cluster with other carnivores, and have carnivore-like levels of phylogenetic diversity (Figures S2 and S3). In folivorous Primates, the simple gut has evolved pouches for fermentation of recalcitrant plant material (9). The fecal microbiota of the two Colobus monkeys and Francois Langur cluster together by UniFrac with the three pig species (Red River Hog, Visayun Warty Pig, Babirusa), the Flying Fox, Baboon, Chimpanzee, Gorilla and Orangutan, forming a phylogenetically-mixed group whose diets include a large component of plant material. This cluster occupies an intermediate position between other primates and herbivorous foregut fermenters in Figure S2. This observation suggests that the Colobus monkeys and François Langur harbor microbial lineages typical of omnivores, but have a greater representation of the lineages involved with the breakdown of a plant-based diet. Such host-level selection of specific members of a microbiota has been demonstrated under laboratory conditions by reciprocal transplantations of gut microbiota from one host species to germ-free recipients of a different species: groups of bacteria were expanded or contracted in the recipient host to resemble its ‘normal’ microbiota through a process that may have been influenced by diet (26).

Co-evolution of gut microbiotas and their hosts

Co-evolution has been hypothesized to occur in animal species whose parental care enables vertical transmission of whole gut communities, and where the properties of the community as a whole confer a fitness advantage to the host (29). Although co-evolution has been inferred from observations of bacterial host specificity (30), these observations could also be explained by dietary preference. Therefore, we searched for evidence of co-diversification, a special case of co-evolution (2) that would be manifest in this case by a clustering of fecal microbial communities that mirrors the mammalian phylogeny. A UniFrac analysis was performed recursively (11) on the entire mammalian fecal bacterial tree, using a procedure that had the effect of asking whether the bacterial lineages stemming from each tree node mirrored the mammalian phylogeny (31). The results were compared to those using a randomized version of the mammalian phylogeny. The patterns of community similarity matched the mammal phylogeny more often than would be expected if no co-diversification had occurred (Figure S4; P=1.79×10−11; t = −6.73, df=88).

Although mammalian gut microbes are highly adapted to life in this body habitat, and many lineages are extremely rare outside of it (29), they appear to be fairly promiscuous between hosts. This could account for the spectacular success of mammals and herbivores in particular: acquiring a gut microbiota was not a constraint, and morphological and behavioral adaptations were likely far more restrictive. One implication of this work is that the tolerance of the immune system to gut microbes is a basal trait in mammal evolution.

The global success of humans is based in part on our ability to control the variety and amount of food available using agriculture and cookery. These capabilities have not significantly impacted the major bacterial lineages that constitute our gut microbiota: as noted above, fecal samples from unrelated healthy human samples cluster with other omnivores (Figures 1 and S2), with interpersonal differences (UniFrac distances) being significantly smaller than the distances between humans and all other mammalian species (G=−47.7, P<0.005, n=106). While our interpersonal differences appear to be smaller than inter-species differences among mammals, deeper sampling and analysis will be required to circumscribe the gut microbial diversity inherent to humans: this is one of the early goals of the recently initiated international human microbiome project (1).

Supplementary Material

Methods and Results

Figs S1–S14

Table S1

References

References and Notes

- 1.Turnbaugh PJ, et al. Nature. 2007;449:804. doi: 10.1038/nature06244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moran NA. Curr Biol. 2006;16:R866. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacFadden BJ. Trends Ecol Evol. 2005;20:355. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerling TE, Ehleringer JR, Harris JM. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998;353:159. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lister AM. Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences. 2004;359:221. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pagani M, Zachos JC, Freeman KH, Tipple B, Bohaty S. Science. 2005;309:600. doi: 10.1126/science.1110063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang Y, et al. Science. 2001;293:1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1060143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cerling TE, et al. Nature. 1997;389:153. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens C, Hume I. Comparative physiology of the vertebrate digestive system. 2. Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckberg PB, et al. Science. 2005;308:1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1110591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.For further details see Supplementary Online Materials.

- 12.Frey JC, et al. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:3788. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.5.3788-3792.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozutsumi Y, Hayashi H, Sakamoto M, Itabashi H, Benno Y. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2005;69:1793. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brooks SP, McAllister M, Sandoz M, Kalmokoff ML. Can J Microbiol. Oct;49:589. 2003. doi: 10.1139/w03-075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Nature. 2006;444:1022. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi H, Sakamoto M, Benno Y. Microbiol Immunol. 2002;46:535. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2002.tb02731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayashi H, Sakamoto M, Benno Y. Microbiol Immunol. 2002;46:819. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2002.tb02769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi H, Sakamoto M, Kitahara M, Benno Y. Microbiol Immunol. 2003;47:557. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2003.tb03418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shannon P, et al. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ley RE, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504978102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huber T, Faulkner G, Hugenholtz P. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2317. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeSantis TZ, et al. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:5069. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:5261. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lozupone C, Hamady M, Knight R. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:371. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lozupone C, Knight R. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8228. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rawls JF, Mahowald MA, Ley RE, Gordon JI. Cell. 2006;127:423. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koch PL, Fogel ML, Tuross N. In: Stable Isotopes in Ecology and Environmental Science. Lajtha K, Michener RH, editors. Blackwell Publishing; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell JB, Rychlik JL. Science. 2001;292:1119. doi: 10.1126/science.1058830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ley RE, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Cell. 2006;124:837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dethlefsen L, McFall-Ngai M, Relman DA. Nature. 2007;449:811. doi: 10.1038/nature06245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arnason U, et al. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102164299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.We thank Sabrina Wagoner, for superb technical assistance, plus Lucinda Fulton, Robert Fulton, Kim Delahaunty, our other colleagues in the Washington University Genome Sequencing Center for their assistance with 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and the Namibian Ministry of Environment and Tourism. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (DK78669; DK70977; DK30292), the W.M. Keck Foundation, and the Ellison Medical Foundation. M.H. was supported by an NIH Molecular Biophysics Training Program (T32GM065103). Sequences (EU458114-475873) were deposited in GenBank.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Methods and Results

Figs S1–S14

Table S1

References