Abstract

The role of non-Smad proteins in the regulation of transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) signaling is an emerging line of active investigation. Here, we characterize the role of KLF14, as a TGFβ-inducible, non-Smad protein that silences the TGFβ receptor II (TGFβRII) promoter. Together with endocytosis, transcriptional silencing is a critical mechanism for down-regulating TGFβ receptors at the cell surface. However, the mechanisms underlying transcriptional repression of these receptors remain poorly understood. KLF14 has been chosen from a comprehensive screen of 24 members of the Sp/KLF family due to its TGFβ inducibility, its ability to regulate the TGFβRII promoter, and the fact that this protein had yet to be functionally characterized. We find that KLF14 represses the TGFβRII, a function that is augmented by TGFβ treatment. Mapping of the TGFβRII promoter, in combination with site-directed mutagenesis, electromobility shift, and chromatin immunoprecipitation assays, have identified distinct GC-rich sequences used by KLF14 to regulate this promoter. Mechanistically, KLF14 represses the TGFβRII promoter via a co-repressor complex containing mSin3A and HDAC2. Furthermore, the TGFβ pathway activation leads to recruitment of a KLF14-mSin3A-HDAC2 repressor complex to the TGFβRII promoter, as well as the remodeling of chromatin to increase histone marks that associate with transcriptional silencing. Thus, these results describe a novel negative-feedback mechanism by which TGFβRII activation at the cell surface induces the expression of KLF14 to ultimately silence the TGFβRII and further expand the network of non-Smad transcription factors that participate in the TGFβ pathway.

The family of cytokines composed of TGFβ,4 bone morphogenetic proteins, activins, inhibins, connective tissue growth factors (CCN family), along with their corresponding signaling molecules, are master regulators of normal homeostasis and development (1–10). Consequently, alterations in these pathways lead to severe malformations and diseases, including cancer. TGFβ is the best characterized pathway within this family of cytokines. Recent studies reveal, for instance, the existence of two types of membrane-to-nucleus TGFβ signaling mechanisms, namely the Smad-dependent and non-Smad protein-mediated cascades, although evidence of cross-talk between these two cascades is also emerging (4, 9). Therefore, even though our understanding of the complexity underlying TGFβ signaling continues to grow, classification into these two types of mechanisms has helped to organize the nascent theoretical framework for advancing this field of research by the integration of new findings into easily understandable paradigms.

The canonical Smad-mediated TGFβ pathway is activated by binding of TGFβ1, -2, and/or -3 cytokines to the TGFβRII, which then dimerizes with and activates the TGFβ receptor I through serine phosphorylation of the regulatory GS-domain. The Type I receptor, in turn, phosphorylates receptor-bound Smad (Smad2/3) at the C-terminal SXS motif, releasing them from retention in the cytoplasm and allowing their translocation into the nucleus. Smad4 acts as a common partner of activated Smads to help execute their function. In this manner, TGFβ signaling is transduced through the cytoplasm into the nucleus to form complexes with distinct transcriptional regulators for specific gene promoters.

The role of non-Smad protein-mediated pathways in the regulation of TGFβ signaling is also an active line of investigation. For instance, the Sp/KLF family of proteins is emerging as important non-Smad protein-mediated pathway cascades and, under certain circumstances, a cross-talk regulator with Smads to achieve distinct cellular functions. Sp1 is the founding member this expanding group of Sp/KLF proteins. The structure of these proteins is defined by the presence of three highly conserved and homologous C-terminal Cys2His2 zinc finger domains, which are responsible for DNA binding, and a variable N-terminal domain, which is responsible for transcriptional regulation (11–13). However, the identification and characterization of this family of proteins has revealed that many bind to GC-rich target sequences similar, if not identical to, the “Sp1 sites” through which they can either activate or repress gene expression (11–13). Therefore, the discovery of repressors within this Sp/KLF family of transcriptional regulators has challenged the early paradigm that Sp1 activates all GC-rich sites. As a result, these Sp/KLF transcriptional repressors provide a novel mechanism for silencing a large number of genes that are already known to be activated by Sp1, particularly in response to TGFβ.

TGFβRII has been previously shown to be activated by Sp1 (14). However, since these elegant studies were done, 24 Sp/KLF transcription factors have been discovered with some members acting as activators while others as repressors via the same type of GC-rich cis regulatory sequences used by Sp1. Thus, some Sp/KLF transcription factors are excellent candidates that may play a role in silencing of TGFβRII. Indeed, fortunately, in the current study, we describe, for the first time, the functional characterization of KLF14 as a novel non-Smad regulatory protein of the TGFβ pathway. Our results outline a novel, biochemically significant role for KLF14 in the silencing of the TGFβRII via Sp/KLF sites. This pathway provides a well characterized example of how Sp/KLF proteins are emerging as important non-Smad proteins that can directly regulate TGFβ signaling by regulating the expression of key molecules from this pathway.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture—Tissue culture reagents were purchased from commercial sources (Invitrogen). The human pancreatic epithelial cancer cell lines, PANC-1, ASPC-1, Capan-1, Capan-2, BxPC-3, L3.6, MiaPaCa-2, and CFPAC-1, were obtained from American Type Culture Collection and maintained according to the supplier's suggestions. All cells were grown at 37 °C in a humidified incubator under 5% CO2.

Plasmid Construction—Standard molecular biology techniques were used to clone KLF4, KLF5, KLF7, KLF9, KLF11, KLF14, and KLF15 into the pcDNA3.1/His (Invitrogen) and pCMVtag2 (Stratagene) vectors for expression as His-tagged or FLAG-tagged proteins, respectively, as well as the truncated (263 bp) TGFβRII promoter into the pGL3-Lux vector (Promega). The p3TP-Lux reporter plasmid containing TGFβ-responsive elements was kindly provided by Dr. Anita Roberts (National Institutes of Health) as a positive control for TGFβ1 stimulation experiments (data not shown). Full-length TGFβRII reporter was kindly provided by Dr. David Danielpour (Case Western).

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR—Total RNA was extracted from cells according to the manufacturer's instructions using an RNeasy Kit (Qiagen), and 5 μg was used for cDNA synthesis using oligo(dT) primer using the SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer's protocol. RT-PCR was performed using LA TaqDNA Polymerase with a GC Buffers kit (Takara) per the manufacturer protocols. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed with the primer sets provided in supplemental Table S1. Each experiment was done in triplicate. Amplification of four human housekeeping genes, GAPDH (Unigene Hs.544577), β2-microglobulin (B2M, Hs.709313), β2-Tubulin (TUBB2, Hs.300701), and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT1, Hs.412707) was used for all samples as an internal control. Densitometric values were obtained and normalized to the average of the housekeeping cDNAs for each individual sample using Scion Image Beta 4.02 software (Scion Corp.).

To represent the TGFβ inducibility of individual KLF transcripts, each TGFβ-treated sample was compared with an untreated control that was originally plated and ultimately collected at the same time to minimize compounding factors, which can often influence gene expression (i.e. cell cycle stage, cell density, potential unknown paracrine, and/or autocrine stimuli). At each time point, values were determined by first normalizing the TGFβ-treated sample (T, treated) to the average of the four aforementioned housekeeping genes in the same sample (TC, treated housekeeping gene control). This resultant value was divided by the corresponding untreated sample (UT, untreated) normalized in the same manner (UTC, untreated housekeeping gene control), to express the fold of TGFβ induction ([T/TC]/[UT/UTC] = fold TGFβ-induction). Another housekeeping gene, β-actin (ACTB, Hs.520640), was not used in our analyses, because it showed significant differences with TGFβ treatment over control values (data not shown).

Western Blot—Total protein extracts were prepared by lysing cells in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer supplemented with Complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). Cellular lysates were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and then separated proteins are transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C in blocking solution (Tris-buffered saline solution containing 5% nonfat dried milk and 0.1% Tween 20). Subsequently, membranes were incubated with specified primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Immune complexes were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce) and exposed to x-ray film. An antibody against β2-actin (Sigma) was used as loading control.

Transcriptional Reporter Assays—Cells were transfected with specified reporter constructs along with expression constructs and/or empty vector using electroporation (2 × 106 cells/0.4-cm microcuvette, 360 V, and 10 ms) and subsequently serum-starved overnight. Transfection was performed with equimolar concentrations of DNA, and expression was quantified with Western blotting directed against epitope-tagged proteins as described. Cells were stimulated with TGFβ1 (R&D Systems) as specified and assayed at various specified time points. At 24 or 48 h after transfection and treatment as noted, cells were lysed, and luciferase measurements were performed using a 20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs) according to manufacturer's suggestions (Promega). Data were normalized as relative light units and normalized to the protein concentration as the mean ± S.D. All experiments were performed in triplicate at least three independent times.

Immunoprecipitation—Cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged constructs. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were washed and lysed in lysis buffer (150 mm NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 20 mm MgCl2) supplemented with Complete protease inhibitor tablets (Roche Applied Science) for 30 min at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitations were performed using anti-FLAG M2 agarose-conjugated antibodies (Sigma) for 2 h at 4 °C. To detect interaction with endogenous co-repressors, immunocomplexes were collected by centrifugation, washed with lysis buffer, and analyzed by Western blot as described above using anti-mSin3a and HDAC2 antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation—ChIP assays were performed using the EZ-ChIP kit. The following primer set for the 263-bp TGFβRII promoter was used for PCR: 5′-GCA GAT GTT CTG ATC TAC TA-3′ (forward); 5′-AGC TGG GCA GGA CCT CTC TC-3′ (reverse) using TaKaRa LA Taq according to the manufacturer's protocol (Mirus).

Site-directed Mutagenesis—Site-directed mutagenesis was performed with QuikChange® II site-directed mutagenesis kits per the manufacturer's protocol (Stratagene). All constructs were sequenced by the Mayo Clinic Molecular Biology Core Facility.

GST Fusion—The KLF14 cDNA fragment encoding amino acids 191–323 corresponding to the DNA-binding zinc finger region was cloned into the GST fusion vector pGEX 5X-1 (Amersham Biosciences) using standard techniques. GST fusion protein expression was induced in BL21 cells (Stratagene) by the addition of 1 mm isopropyl-d-thiogalactopyranoside and incubation for 2 h. Cells were lysed and subsequently purified by using glutathione-Sepharose 4B affinity chromatography as previously described (15).

Electromobility Shift Assay—Gel shift assays were performed as previously described (16). Briefly, 1.75 pmol of double-stranded oligonucleotides were end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP using 10 units of T4 polynucleotide kinase and appropriate buffer (700 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 100 mm MgCl2, 50 mm dithiothreitol) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). The reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min and halted with addition of TE plus EDTA (0.5 m EDTA, 1 m Tris, pH 8.0, H2O). Protein lysates included 0.5 μg of purified GST-KLF14/ZF fusion protein and in some experiments rhSP1 (Promega) at the indicated dilutions. A 5× ZnCl2 buffer was used in this reaction (100 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 250 mm KCl, 25 mm MgCl2, 50 μm ZnCl2, 30% glycerol, 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 250 μg/ml poly(dI-dC), H2O) for 10 min at room temperature. The γ-32P-labeled oligonucleotides were added for 20 min. In some cases, an excess of cold probe, at the indicated dilutions, was added concomitant with the addition of radiolabeled probe in addition to anti-Sp1 polyclonal rabbit antibody purchased from commercial sources (Millipore). The mixtures were electrophoresed in a 4% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in a Hoeffer midi-gel using 0.5× Tris borate-EDTA for ∼4 h at 160 V. Gels were then transferred to blotting paper (Whatman 3MM), covered in plastic wrap, and vacuum dried for 1.5 h at 65 °C. Dried gels were then analyzed using a Storm Scanner 860 PhosphorImager (Amersham Biosciences). Sp1 consensus and Sp1 mutant double-stranded oligonucleotides were obtained from commercial sources (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) with the following sequences: Sp1 consensus, 5′-ATT CGA TCG GGG CGG GGC GAG C-3′ (forward); 5′-GCT CGC CCC GCC CCG ATC GAA T-3′ (reverse) and Sp1 mutant, 5′-ATT CGA TCG GTT CGG GGC GAG C-3′ (forward); 5′-GCT CGC CCC GAA CCG ATC GAA T-3′ (reverse).

RESULTS

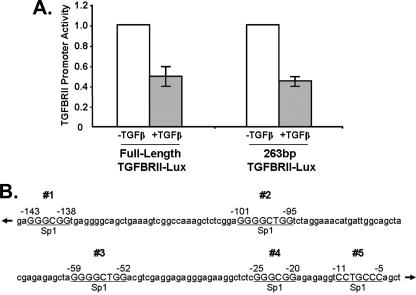

A Yet Undefined Sp/KLF Repressor Protein Plays a Role in Silencing of the Type II TGFβ-receptor Promoter—Previous studies have described the regulation of the TGFβRII by TGFβ ligands, primarily showing a bimodal response consisting of an Sp1-dependent up-regulation (14, 17) and a subsequent down-regulation of receptor transcript levels upon this stimulation (18–20). Interestingly, although the activation of TGFβRII promoter, in particular by Sp1, has received precise attention, how this receptor is repressed remains poorly understood. Consequently, the major goal of the current study has been to characterize the role of a specific family of non-Smad proteins (Sp/KLF transcription factors), which may functionally explain the down-regulation TGFβRII through GC-rich Sp1-like sequences. Our studies began with examination of the transcriptional activity of the TGFβRII gene promoter in PANC1 epithelial cells, a widely used model for studying TGFβ signaling. We have performed an initial series of reporter assays using full-length TGFβRII and the previously described, TGFβ-sensitive, 263-bp core promoter, which is located 5′ of the transcriptional start site (14). Treatment of PANC1 cells with exogenous TGFβ1 leads to a marked reduction in activity of the full-length TGFβRII reporter when compared with untreated control cells (Fig. 1A). This silencing effect is recapitulated in the 263-bp TGFβRII core promoter, suggesting that both the previously described activation pathway (14) and the negative transcriptional regulatory mechanism characterized further here (Fig. 1A), are operational at this core promoter level. Using bioinformatics analyses (TRANSFAC Public), we have identified five putative Sp/KLF binding sites within this TGFβ-sensitive, 263-bp core promoter region (Fig. 1B). Four of these sites (#1–4) have been previously identified, although an additional site (#5) has not been previously reported (14, 21). Some of these previously identified sites have been shown to be activated by Sp1. However, whether novel Sp/KLF silencer proteins can also bind to this sequence to reverse the activation by Sp1 remained unknown. Therefore, this analysis has led us to the hypothesis that a yet undefined Sp/KLF repressor protein plays a role in the silencing of this promoter.

FIGURE 1.

A, repression of the TGFβRII promoter occurs after 24 h of TGFβ stimulation in Panc1 cells. Panc1 cells were transfected with a full-length and a truncated 263-bp TGFβRII promoter luciferase reporter and then stimulated with TGFβ1 after overnight serum starvation. Luciferase levels were obtained at specified time points after treatment and compared with untreated controls. Values were normalized to lysate protein concentrations and relative to untreated controls. Data are the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments, with triplicates for each experiment. B, TGFβRII promoter has five putative “Sp1” binding sites. The diagram represents a schematic of the human TGFβRII proximal promoter containing five GC-rich Sp1-like elements.

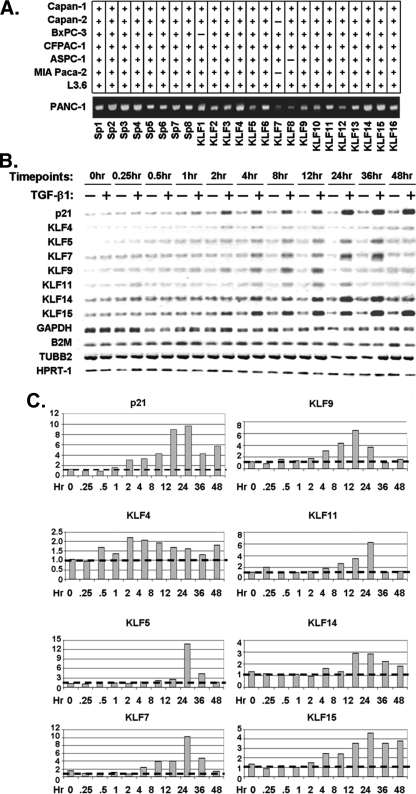

Novel TGFβ-inducible Non-Smad, Sp/KLF Proteins Are Identified as Candidate Regulators of the Type II TGFβ-receptor— To test our hypothesis, we have developed a four-tier screening approach. This approach includes first, testing which of the 24 known Sp/KLF proteins are expressed in TGFβ-sensitive epithelial cells and, thus, can be considered initial candidates to target the TGFβRII promoter. Our experimental cell model, PANC1, a human epithelial cell line, is an optimal model for our studies, because they have adequate expression of TGFβRII mRNA and display growth inhibition to exogenous TGFβ1 stimulation (22). In addition, as shown in Fig. 2A, each of the 24 known Sp/KLF transcription factors are consistently expressed in these cells, which made it ideal for performing a comprehensive screen. Second, we determine whether any Sp/KLF genes are TGFβ-inducible with a kinetic that is consistent with playing a role in the down-regulation of the TGFβRII. Third, by utilizing transfection studies combined with reporter assays, we test the potential of distinct members of this family to repress TGFβRII promoter activity and then, by electromobility shift assays, determine which sites on the promoter are utilized by our candidate KLF protein. Finally, we examine whether the repressor that is isolated according to these criteria binds to the endogenous TGFβRII gene and can remodel chromatin on this target, suggesting the bona fide target status of the candidate KLF protein. Thus, by applying this comprehensive screening, our study has been robust in evaluating the KLF protein family in the TGFβ response and regulation of the TGFβRII.

FIGURE 2.

A, eight pancreatic cancer cell lines were screened by RT-PCR for expression of 24 members of the Sp/KLF family of transcription factors. The figure shows that all 24 Sp/KLF members are expressed in the TGFβ-sensitive Panc1 cell line. B, TGFβ1 induces the expression of several KLF family members. Panc1 cells were serum-starved overnight, treated with 10 ng/ml TGFβ1, and screened for the expression of each KLF gene by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. The expression levels for each KLF gene from TGFβ1-treated samples were compared with untreated controls and normalized to housekeeping genes as described under “Material and Methods.” The expression of the p21 gene was used as a positive control for TGFβ1 treatment. Four different housekeeping genes, namely GAPDH, B2M, TUBB2, and HPRT1, were used as internal standards for normalization. C, quantification of TGFβ induction of transcript levels over time. At each time point, values were determined by first normalizing the densitometric measurement of the TGFβ-treated sample to the average of four housekeeping genes (GAPDH, B2M, TUBB2, and HPRT1) in the same sample. This resulting value was divided by the corresponding value of the untreated sample normalized in the same manner in order to express the -fold of TGFβ induction.

The genomic axiom that functionally related genes follow a similar pattern of expression suggested that, hypothetically, the protein that represses the TGFβRII may be expressed in a similar manner after TGFβ treatment, in particular, during the repression response to this cytokine. Consequently, we have evaluated which, if any, of these Sp/KLF members are inducible by TGFβ1 treatment. Thus, using RNA from PANC1 cells either untreated or treated with TGFβ1, we have performed RT-PCR at various time points (Fig. 2B). As a positive control for TGFβ-mediated transcriptional induction, we monitor the expression of p21, a known TGFβ-inducible gene within the pathway. Of the 24 known Sp/KLF transcription factors, we have identified 7 that were markedly induced with exogenous TGFβ1 treatment, suggesting that these could be potential candidate transcriptional repressors of the TGFβRII promoter (Fig. 2B). These results are not only consistent with our previous work, which identified KLF11 as a TGFβ-inducible gene (16, 23), but, more importantly, it characterizes previously unidentified KLF targets for this cascade, namely KLF4, -5, -7, -9, -14, and -15. Thus, based upon their expression patterns, these seven genes are good candidates to further investigate their regulation of the TGFβRII promoter.

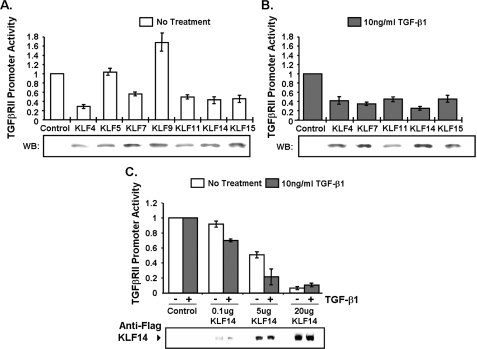

Subsequently, we have tested the transcriptional activity of these candidates on the TGFβRII promoter using reporter assays by co-transfecting the 263-bp core TGFβRII promoter-luciferase construct with cDNAs encoding each of the seven TGFβ-inducible KLF candidates. Out of these, five candidates induced a marked decrease in TGFβRII promoter activity, namely KLF4, -7, -11, -14, and -15 (Fig. 3A). KLF5 did not affect TGFβRII promoter activity above control levels, whereas KLF9 appeared to slightly activate this promoter, therefore these two proteins were not continued in subsequent experiments due to our objective of identifying TGFβRII repressors. To confirm whether this observed repression of TGFβRII promoter regulation is consistent with TGFβ pathway activation, these five proteins were further tested in PANC1 cells treated with exogenous TGFβ1 treatment. Interestingly, upon treatment, these KLF proteins were capable of further repressing TGFβRII promoter activity, with the largest repression achieved by KLF14 (Fig. 3B). These data also indicate that a second TGFβ-dependent mechanism, directly (signal-induced KLF expression or post-translational modifications) or indirectly (induction of another transcription factor), cooperates with KLF proteins to additionally repress this gene. Upon increasing concentrations of KLF14 cDNA in transfection studies, we found a concentration-dependent repression of the core TGFβRII promoter (Fig. 3C). Together, these results strongly identify KLF14 as a good candidate to be a regulator of TGFβRII promoter activity and expression.

FIGURE 3.

A, Panc1 cells were transfected with KLF(FLAG/His) epitope-tagged expression constructs or control empty vector to test TGFβRII promoter activity. B, Panc1 cells were transfected with indicated KLF(FLAG/His) epitope-tagged expression constructs or control vector and then stimulated with 10 ng/ml TGFβ1 after overnight serum starvation to test TGFβRII promoter activity. C, Panc1 cells were transfected with various concentrations of epitope-tagged KLF14(FLAG) expression construct or control vector and then stimulated with 10 ng/ml TGFβ1 after overnight serum starvation to observe the effect on TGFβRII promoter activity. Western controls (FLAG/His) were shown for epitope-tagged KLF expression in all experiments. Expression of FLAG-tagged KLF4, KLF7, KLF14, and KLF15 was confirmed by an anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma), whereas expression of His-tagged KLF5, KLF9, and KLF11 was verified by the OMNI D8 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Data are the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments, with triplicates for each experiment.

KLF14, a Novel Non-Smad Protein, Regulates the Type II TGFβ-receptor—The gene encoding KLF14 has been previously identified by our group and named BTEB5 due to its sequence similarities to members of this subfamily of KLF silencing proteins.5 Although, recently, genetic studies have reported the genomic structure, intronless nature, and potential imprinted status of this gene (24), a functional characterization of this protein at the cellular and biochemical level has never been performed. Because our data indicate that KLF14 appears to be a potent regulator of the TGFβRII in promoter assays combined with this existing gap in knowledge on this KLF family member and its targets, the choice to further investigate the role of this particular KLF in TGFβRII regulation would significantly expand the current knowledge on the functional properties of members of this family.

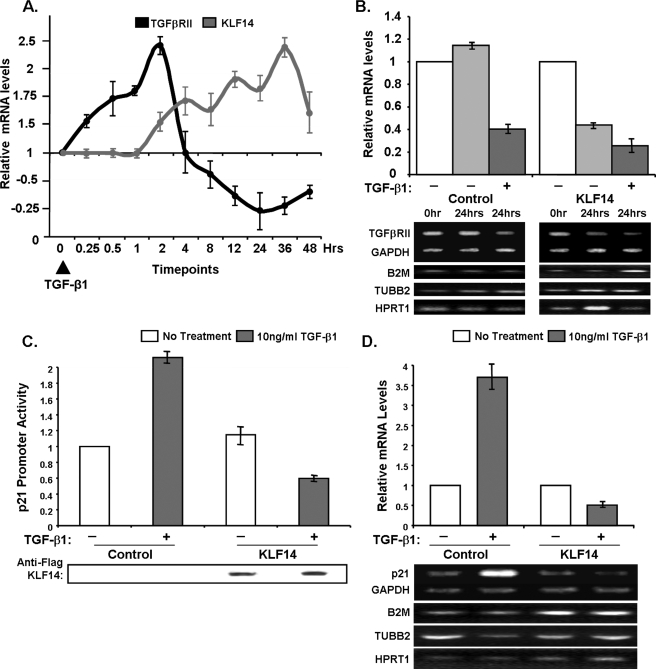

Noteworthy, we have validated these in vitro reporter results in vivo by assessing whether this protein has a regulatory effect on endogenous TGFβRII levels in PANC1 cells. Initial correlative experiments demonstrate that the levels of TGFβRII mRNA levels decrease at a time in which the amount of KLF14 increases (repression phase of the bimodal expression pattern of TGFβRII in response to TGFβ), raising the possibility that KLF14 is induced to subsequently down-regulate the TGFβRII (Fig. 4A). To mechanistically support this correlation, we have performed RT-PCR on cells overexpressing KLF14 to determine TGFβRII levels in comparison to mock transfected cells in the presence or absence of exogenous TGFβ1 stimulation (Fig. 4B). KLF14 overexpression alone is sufficient to decrease TGFβRII mRNA, interestingly to the same extent as TGFβ1 stimulation alone. Furthermore, subsequent TGFβ1 treatment in cells transfected with KLF14 leads to further down-regulation of TGFβRII transcripts. Because KLF14 is a TGFβ-inducible gene, the further decrease in TGFβRII mRNA levels observed upon TGFβ1 treatment likely results from the induction of endogenous Sp/KLF transcription factors by this cytokine. These results suggest that TGFβ down-regulates TGFβRII transcripts through KLF14 expression with subsequent negative regulation of promoter activity. Next, we have tested whether the effect of KLF14 on TGFβRII expression interfered with TGFβ-induced signals that target downstream genes, such as p21 (25). Indeed, as expected, TGFβ1 treatment increases p21 promoter activity, as observed via reporter assays, as well as its mRNA levels (Fig. 4, C and D), whereas KLF14 reduces both p21 promoter activity and mRNA levels upon TGFβ1 treatment (Fig. 4, C and D). These results suggest that KLF14 interferes with the activation of downstream TGFβsignaling effects, at least in part, by its ability to repress the TGFβRII.

FIGURE 4.

A, TGFβRII and KLF14 transcript levels were analyzed by determination of density, and relative transcript levels were represented by the ratio TGFβRII cDNA/GAPDH cDNA and KLF14 cDNA/GAPDH cDNA. Data were the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments. B, KLF14 inhibits endogenous TGFβRII transcript levels. Panc1 cells were transfected with KLF14 or control empty vector and then stimulated with 10 ng/ml TGFβ1 for 24 h after overnight serum starvation. Densitometry was performed after normalizing to the average of GAPDH, B2M, TUBB2, and HPRT1 levels and untreated control cDNA. C, Panc1 cells were transfected with KLF14 FLAG epitope-tagged constructs or control empty vector along with a p21 promoter reporter construct and then stimulated with 10 ng/ml TGFβ1 after overnight serum starvation. Western control for KLF14(FLAG) epitope-tagged protein expression is shown. D, KLF14 inhibits endogenous p21 transcript levels. Panc1 cells were transfected with FLAG-KLF14 or control empty vector and then stimulated with 10 ng/ml TGFβ1 for 24 h after overnight serum starvation. Densitometry was obtained after normalizing to the average of GAPDH, B2M, TUBB2, and HPRT1 levels and untreated control cDNA.

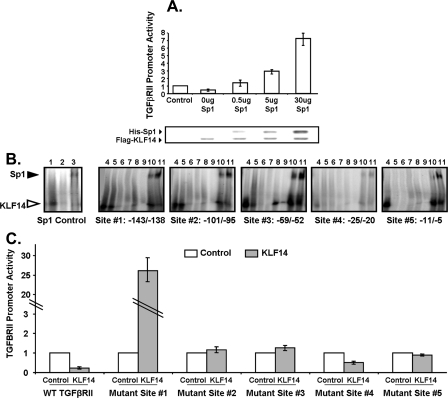

KLF14 Represses the TGFβRII Promoter via Distinct Sp1-like GC-rich Sequences and Competition with Sp1—Repressor KLF proteins, such as KLF14, have been previously shown to compete with the canonical Sp1 protein for overall transcriptional activity of a promoter, such as the CYP1A1 and LDLR promoters (26, 27). Therefore, herein we test the ability of KLF14 to repress transcription of the TGFβRII promoter in the presence of exogenous Sp1 expression. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 5A, the expression of exogenous Sp1 relieves the repression mediated by KLF14 in a dose-dependent manner. Due to the direct, Sp1-dependent up-regulation of the TGFβRII promoter as part of its bimodal response during activation, we dissect whether the repression of the TGFβRII promoter via KLF14 is also acting through a direct mechanism on the promoter rather than indirect due to KLF14 mediating a secondary effector.

FIGURE 5.

A, KLF14 and Sp1 compete to regulate TGFβRII promoter activity. Panc1 cells were transfected with KLF14(FLAG) and Sp1(His) epitope-tagged expression constructs or control empty vector as indicated to evaluate in vivo competition on TGFβRII promoter activity. Western control (FLAG/His) is shown for epitope-tagged expression. Data are the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments, each done in triplicate. B, KLF14 binds to four of the putative Sp1 sites and competes with Sp1 on the TGFβRII promoter. Electromobility shift assay was performed using KLF14-ZF GST fusion proteins and radiolabeled oligonucleotides for each of the five putative Sp1 sites. Lane 1: control-Sp1 consensus oligonucleotide; lane 2: control-Sp1 mutant oligonucleotide; lane 3: Sp1 consensus oligonucleotide and rhSP1 protein; lane 4: WT oligonucleotide; lane 5: mut#1 oligonucleotide; lane 6: mut#2 oligonucleotide; lane 7: WT oligonucleotide and 25× cold probe; lane 8: WT oligonucleotide and 100× cold probe; lane 9: WT oligonucleotide and anti-GST; lane 10: WT oligonucleotide and 1× rhSp1 protein; lane 11: WT oligonucleotide and 5× rhSp1 protein. KLF14 band (open arrowhead). Sp1 band (closed arrowhead). The depicted blots are representative of triplicate experiments. C, KLF14 utilizes four Sp/KLF sites to repress the TGFβRII promoter in vivo. Panc1 cells were transfected with TGFβRII-luciferase with mutated Sp1 sites as indicated and stimulated with 10 ng/ml TGFβ1 after overnight serum starvation, and transcriptional activity was measured and normalized to control empty vector. Data are the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments, with triplicates for each experiment.

Thus, to first delineate the DNA binding properties of KLF14 to the promoter of TGFβRII in vitro, we characterize the five putative Sp/KLF sites (shown in Fig. 1B) by electromobility shift assay (Fig. 5B). In this experiment, radiolabeled oligonucleotides for each of the 5 Sp1 sites have been created as well as mutants for each site containing either 2- or 4-nucleotide substitutions (mut#1 or mut#2, respectively) within the GC-rich binding sequence. Sp1-consensus oligonucleotides and respective mutants have been used as internal binding controls (Fig. 5B, lanes 1–3). The interaction between a recombinant KLF14 zinc finger DNA-binding domain and four of the Sp/KLF site probes (#1–3 and 5) is specific as indicated by the fact that an excess of unlabeled probe competes with the radiolabeled probes (Fig. 5B, lanes 7 and 8). Furthermore, we were able to abolish this binding by using antibodies against the recombinant KLF protein (anti-GST antibody), thus confirming specificity of the complex (Fig. 5B, lane 9). Further specificity is evidenced by the impaired ability of recombinant KLF14 protein to bind to mutated Sp/KLF probes (Fig. 5B, lanes 5 and 6). Visible but reduced binding is noted with the 2-bp mutant probes (mut#1, lane 5) for sites #1–3, however a significant loss of binding was observed with the 4-bp mutant probes (mut#2, lane 6) at all sites. Moreover, through addition of recombinant Sp1 protein to the reaction, an increase in the concentration of Sp1 diminished the binding of KLF14, demonstrating that KLF14 and Sp1 compete for these GC-rich binding sites (Fig. 5B, lanes 10 and 11), complementing the competition results we observed in vivo (Fig. 5A). Only a weak complex was visualized with site #4, indicating that this site was less specific for KLF14 binding than the other four sites.

To functionally complement these studies, we have performed TGFβRII reporter assays with both wild-type and mutant promoter-luciferase constructs. Site-directed mutagenesis has been utilized to create a 2-nucleotide substitution in each of the 5 GC-rich Sp/KLF sites (Fig. 5C). These assays resulted in a marked loss of the repression observed with the wild-type TGFβRII promoter upon KLF14 overexpression with mutation in Sp/KLF sites #1, 2, 3, and 5, particularly with a significant gain of transcriptional activity upon mutating site #1. These findings demonstrate that these four are operational to silence the transcriptional activity of the TGFβRII promoter by KLF14. Furthermore, we did not observe a significant loss of repression with mutation of site #4 with KLF14 overexpression, which supports our finding of negligible binding of KLF14 to this specific Sp/KLF site (Fig. 5B). All together, KLF14 appears to bind and act on four of the GC-rich sites of the TGFβRII promoter to repress its transcriptional activity, and this occurs through a mechanism that includes, at least in part, competition with Sp1.

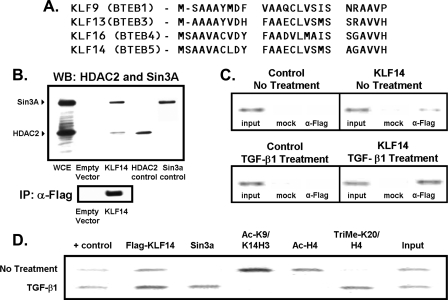

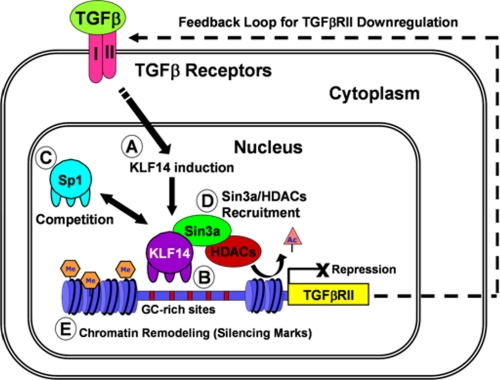

Repression of the TGFβRII Gene by KLF14 Occurs via Mechanisms Involving Chromatin-modifying Enzymes—Careful examination of KLF14 sequence reveals a 26-amino acid domain that is highly similar to repression domains of KLF9 (BTEB1), KLF13 (BTEB3), and KLF16 (BTEB4) proteins (Fig. 6A), which we have previously shown to repress transcription by recruiting Sin3a via its paired amphipathic helix 2 domain, as well as HDAC (15, 28). Interestingly, other studies have found that HDAC inhibition leads to transcriptional activation of the TGFβRII promoter in various cancer cell lines, raising the possibility that a repressor of this type may be operational to achieve this effect (29, 30). Thus, we have tested whether KLF14 does indeed interact with Sin3a and HDAC by immunoprecipitating full-length FLAG-tagged KLF14 from PANC1 cells. The presence of Sin3a and HDAC complexed to KLF14 is detected by Western-blot analysis (Fig. 6B). Thus, these results indicate that KLF14 interacts with Sin3a and HDAC in mammalian cells, implying that these proteins are part of a repressor complex. Subsequently, we have investigated whether this repressor complex occupies the endogenous TGFβRII promoter in vivo via ChIP assays. First, we find that KLF14 indeed binds to the TGFβRII promoter (Fig. 6C). Moreover, congruent with our data using promoter assays (Fig. 6C), treatment with TGFβ1 increases the amount of KLF14 bound to the TGFβRII promoter. In addition, the treatment with TGFβ1 coincides with the appearance of Sin3a on the same region of the promoter as KLF14, further implicating this repressor complex in the mechanism of KLF14 repression of the TGFβRII promoter (Fig. 6D). To gain insight into the type of chromatin remodeling that accompanies KLF14 and Sin3a occupation, we also have performed ChIP using antibodies to various histone marks. Interestingly, we find that, under native conditions, acetylated histones H3 and H4 are present on the TGFβRII promoter; however, upon TGFβ1 treatment, these fall to negligible levels, indicating a change from a transcriptionally “active,” acetylated state to a relatively “inactive,” non-acetylated state (Fig. 6D). Moreover, we observe that, although methylated K20 H4, a mark of repression (31), is not present under native conditions, it occupies the promoter upon TGFβ1 treatment along with Sin3a (Fig. 6D). These types of experiments are in agreement with the “histone code hypothesis” (32), revealing that the state of chromatin in the TGFβRII promoter appears to switch from “active” to “repressed” upon KLF14 occupation after treatment with TGFβ1, all consistent with the idea that KLF14 binds to the TGFβRII promoter to cause repression (Fig. 6, C and D). Therefore, both competition with Sp1 and direct repression via the N-terminal domain, are likely to behave as a dual mechanism of repression that would make it more difficult to reverse than if one of them was operational. This redundancy would ensure that the promoter remains silent even under circumstances that inactivate either of the single mechanisms (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 6.

A, alignment displaying the 26-amino acid Sin3-interacting domain of KLF14 similar to other KLF repressors, KLF9, KLF13, and KLF16. B, HDAC2 and mSin3a form a complex with KLF14 in vivo. Panc1 cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged KLF14 or control empty vector constructs and FLAG-immunoprecipitated. Immunoprecipitated complexes were then probed with antibodies against various known corepressors. WCE, whole cell extract. C, KLF14 occupies the TGFβRII promoter in vivo. Panc1 cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged KLF14 or control empty vector constructs and subject to chromatin immunoprecipitation. A 263-bp fragment of the TGFβRII promoter was amplified by PCR from anti-FLAG or mock immunoprecipitated DNA samples. Note that the TGFβRII promoter was amplified from anti-FLAG (α-FLAG) but not mock immunoprecipitated samples (mock) transfected with KLF14. The input shows the presence of the TGFβRII promoter prior to immunoprecipitation. D, TGFβ1 leads to repressive chromatin modifications upon KLF14 occupation of the TGFβRII promoter. Panc1 cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged KLF14 and treated with TGFβ1 and chromatin landscape ChIP assay was performed using specified antibodies.

FIGURE 7.

Model of KLF14-mediated TGFβRII silencing. Activation of the TGFβRII would occur via TGFβ1 ligand initiating an up-regulation of the TGFβRII promoter by Sp1. In our model, activation of the TGFβ pathway also causes an induction of KLF14 expression (A), which would, in turn, bind to the TGFβRII promoter through its GC-rich sites (B), competing away Sp1 (C), recruiting the Sin3a/HDAC complex (D), and remodeling chromatin from a transcriptionally “active,” acetylated state to an “inactive” state with silencing methyl marks (E). Thus, KLF14 mediates a negative feedback loop to down-regulate the type II TGFβ receptor upon TGFβ stimulation.

DISCUSSION

The current study provides us with several novel mechanistic insights on the regulation of the TGFβ pathway. For instance, the data reported here represent the first functional characterization of the KLF14 protein, outline a novel pathway for the silencing of the TGFβRII promoter, provide insight into the molecular mechanisms by which these phenomena are achieved, and report additional TGFβ-inducible, KLF proteins that are good candidates to regulate this promoter. These findings are of significant relevance to the areas of KLF proteins, TGFβ signaling, the maintenance of cell homeostasis, and their potential contribution to disease states.

TGFβ1 ligand itself may play a role in regulating signaling by down-regulating the cell surface receptor and thus abrogating downstream messages. Others have also shown that the TGFβ receptors are under autoregulation control by ligand stimulation (18). It has been previously shown that treatment with TGFβ1 leads to down-regulation of TGFβRII levels (19). Derynck and colleagues (20) have previously described a process in osteoblastic differentiation in which at first there is a marked up-regulation of TGFβ1 and sensitivity followed by marked down-regulation of receptors and insensitivity to TGFβ1. Furthermore, recent in vitro studies on the biosynthesis of the receptors indicate that the half-life of TGFβRII is ∼60 min and is further reduced to 45 min in the presence of exogenous TGFβ1 (33). Therefore, understanding how this down-regulation of the TGFβRII promoter occurs is of primary biological importance for better understanding TGFβ signaling.

In this regard, the current study reports several novel observations of significant biochemical relevance for extending our knowledge of TGFβ signaling regulation by non-Smad proteins. For instance, this study represents the first functional characterization of KLF14 as a novel TGFβ-inducible repressor protein that mediates silencing of the TGFβRII, and the mechanisms by which this phenomenon occurs, in particular the role of corepressors and chromatin modifications on the TGFβRII promoter. Previous promoter studies have primarily focused on the role of Sp1 in the activation of this promoter. However, recent studies have uncovered a paradoxical behavior for this promoter, namely that histone deacetylase inhibitors are needed to activate this promoter (34, 35). These data point to the existence of a repressive state of this promoter, which is less likely to be regulated by Sp1 but rather by Sp/KLF repressors of the type previously described by our laboratory (11). However, in the current study, rather than looking for a candidate gene within the family of KLF repressors, we have performed an unbiased screening for the TGFβ inducibility of each of the 24 KLF transcription factors and find that KLF14 is up-regulated upon TGFβ treatment and also can efficiently repress the TGFβRII. Interestingly, we demonstrate that there is a strong inverse correlation between expression patterns in a temporal manner of TGFβRII mRNA and KLF14 mRNA in human pancreatic cancer cells. Expression of exogenous KLF14 decreases the level of transcription from the TGFβRII promoter, implying a repressive role for KLF14 in TGFβRII expression.

Further analysis reveals the mechanism by which this protein works, indicating that KLF14 is a member of the Sin3-dependent KLF repressors. This is important in light of there being two types of repressors in this family as recently reviewed by us (11), the Sin3a-dependent proteins, which include KLF9, -10, -11, -16, and now -14, and the CtBP-dependent proteins, such as KLF3 and -8. This knowledge can now be very useful for performing rapid screening of the proteins that may be acting as repressors of particular genes, besides the traditional HDAC inhibitor experiments. This screening, we propose, can utilize siRNA to either target CtBP or Sin3a. An abolition of the silencing activity would then rapidly focus the investigations on a reduced number of candidates belonging to each of these groups. In addition to the recruitment of a KLF14-mSin3A-HDAC2 repressor complex to the TGFβRII promoter, we observed a concurrent remodeling of chromatin, which involves loss of transcriptionally “active” acetylated histone marks and an increase in histone marks that associate with transcriptional silencing. Finally, we defined binding sites involved in KLF14-mediated repression of the TGFβRII promoter, namely sites -143/138 (#1), -101/-95 (#2), -59/52 (#3) and -11/-5 (#5), which are consistent with previously reported Sp1 sites, and these same sites, when mutated, lose the repressive effect of KLF14.

Overall, however, the major relevance of this study is the fact that it contributes to organize our thoughts on how TGFβ signaling is regulated. It has recently been appropriately proposed to classify these mechanisms by whether they are directly mediated by Smads (the best studied to date) or those less understood events regulated by non-Smad proteins (4). In fact, our laboratory has previously described a role for KLF repressors, namely KLF10 (TIEG1) and KLF11 (TIEG2), as non-Smad effectors of the TGFβ response in cell growth (9, 36). Now, due to the findings reported in the current study, we can propose a model wherein TGFβ cytokines activate and repress the TGFβRII promoter using the very same GC-rich sites utilized by this family of proteins. Activation would occur in an initial phase via Sp1, whereas inhibition would follow activation and require the action of KLF14, competition of Sp1, recruitment of Sin3a, HDAC, and distinct chromatin modifications on the promoter (see model in Fig. 7). Therefore, KLF14 becomes another important non-Smad protein, in which at least one of its functions is to silence the TGFβRII. This novel transcriptional pathway thus becomes an important step for modulating the activity of TGFβ signaling.

Supplementary Material

We dedicate this manuscript to the memory of Kazimierz Truty and to all the other patients who have succumbed to pancreatic cancer.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant DK 52913. This work was also supported by Mayo Clinic Pancreatic SPORE (Grant P50 CA102701 to R. U.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Author's Choice—Final version full access.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β; TGFβRII, TGFβ receptor type II; CMV, cytomegalovirus; RT, reverse transcription; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; B2M, β2-microglobulin; TUBB2, β2-Tubulin; HPRT1, hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1; GST, glutathione S-transferase; HDAC, histone deacetylase; WT, wild type; KLF14, Krüppel-like factor 14; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Reported by J. Kaczynski and R. Urrutia to NCBI, 2002.

References

- 1.Zavadil, J., and Bottinger, E. (2005) Oncogene 24 5764-5774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Truty, M., and Urrutia, R. (2007) Pancreatology 7 423-435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raftery, L., and Sutherland, D. (1999) Dev. Biol. 210 251-268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moustakas, A., and Heldin, C. (2005) J. Cell Sci. 118 3573-3584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyazono, K., Maeda, S., and Imamura, T. (2005) Cytokine & Growth Factor Rev. Bone Morph. Prot. 16 251-263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Massague, J., and Gomis, R. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580 2811-2820, Istanbul Special Issue [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knight, P., and Glister, C. (2006) Reproduction 132 191-206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itman, C., Mendis, S., Barakat, B., and Loveland, K. (2006) Reproduction 132 233-246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellenrieder, V., Fernandez Zapico, M., and Urrutia, R. (2001) Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 17 434-440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bachman, K., and Park, B. (2005) Curr. Opin. Oncol. 17 49-54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lomberk, G., and Urrutia, R. (2005) Biochem. J. 392 1-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Black, A. R., Black, J. D., and Azizkhan-Clifford, J. (2001) J. Cell Physiol. 188 143-160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner, J., and Crossley, M. (1999) Trends Biochem. Sci. 24 236-240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bae, H. W., Geiser, A. G., Kim, D. H., Chung, M. T., Burmester, J. K., Sporn, M. B., Roberts, A. B., and Kim, S. J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 29460-29468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang, J. S., Moncrieffe, M. C., Kaczynski, J., Ellenrieder, V., Prendergast, F. G., and Urrutia, R. (2001) Mol. Cell Biol. 21 5041-5049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook, T., Gebelein, B., Mesa, K., Mladek, A., and Urrutia, R. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 25929-25936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venkatasubbarao, K., Ammanamanchi, S., Brattain, M. G., Mimari, D., and Freeman, J. W. (2001) Cancer Res. 61 6239-6247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodward, T. L., Dumont, N., O'Connor-McCourt, M., Turner, J. D., and Philip, A. (1995) J. Cell Physiol. 165 339-348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishikawa, Y., Wang, M., and Carr, B. I. (1998) J. Cell Physiol. 176 612-623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gazit, D., Ebner, R., Kahn, A. J., and Derynck, R. (1993) Mol. Endocrinol. 7 189-198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jennings, R., Alsarraj, M., Wright, K. L., and Munoz-Antonia, T. (2001) Oncogene 20 6899-6909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider, D., Kleeff, J., Berberat, P. O., Zhu, Z., Korc, M., Friess, H., and Buchler, M. W. (2002) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1588 1-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subramaniam, M., Harris, S. A., Oursler, M. J., Rasmussen, K., Riggs, B. L., and Spelsberg, T. C. (1995) Nucleic Acids Res. 23 4907-4912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker-Katiraee, L., Carson, A. R., Yamada, T., Arnaud, P., Feil, R., Abu-Amero, S. N., Moore, G. E., Kaneda, M., Perry, G. H., Stone, A. C., Lee, C., Meguro-Horike, M., Sasaki, H., Kobayashi, K., Nakabayashi, K., and Scherer, S. W. (2007) PLoS Genet. 3 665-678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koutsodontis, G., Moustakas, A., and Kardassis, D. (2002) Biochemistry 41 12771-12784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaczynski, J., Conley, A. A., Fernandez-Zapico, M. E., Delgado, S. M., Zhang, J. S., and Urrutia, R. (2002) Biochem. J. 366 873-882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Natesampillai, S., Fernandez-Zapico, M. E., Urrutia, R., and Veldhuis, J. D. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 3040-3047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaczynski, J., Zhang, J. S., Ellenrieder, V., Conley, A., Duenes, T., Kester, H., van Der Burg, B., and Urrutia, R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 36749-36756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang, W., Zhao, S., Ammanamanchi, S., Brattain, M., Venkatasubbarao, K., and Freeman, J. W. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 10047-10054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee, B. I., Park, S. H., Kim, J. W., Sausville, E. A., Kim, H. T., Nakanishi, O., Trepel, J. B., and Kim, S. J. (2001) Cancer Res. 61 931-934 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishioka, K., Rice, J. C., Sarma, K., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Werner, J., Wang, Y., Chuikov, S., Valenzuela, P., Tempst, P., Steward, R., Lis, J. T., Allis, C. D., and Reinberg, D. (2002) Mol. Cell 9 1201-1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jenuwein, T., and Allis, C. D. (2001) Science 293 1074-1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koli, K. M., and Arteaga, C. L. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 6423-6427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park, S. H., Lee, S. R., Kim, B. C., Cho, E. A., Patel, S. P., Kang, H. B., Sausville, E. A., Nakanishi, O., Trepel, J. B., Lee, B. I., and Kim, S. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 5168-5174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao, S., Venkatasubbarao, K., Li, S., and Freeman, J. W. (2003) Cancer Res. 63 2624-2630 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook, T., and Urrutia, R. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. 278 G513-G521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.