Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) of the lower extremities are among the highest risk vascular patients for fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction and stroke, and have been traditionally undertreated from a medical perspective. Recent evidence suggests that the incidence of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction and stroke can be substantially reduced among PAD patients if they are treated with antiplatelet therapy, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and in some instances, beta-blockers.

OBJECTIVES:

To characterize practice patterns of drug therapy (antiplatelet, statin, ACEI and beta-blocker) among PAD patients admitted to a tertiary care hospital and to determine the ‘care gap’, defined as the proportion of patients who did not receive therapy among those who were eligible for it.

DESIGN AND METHODS:

Patients with PAD (International Classification of Diseases code 440.2) admitted to the Hamilton General Hospital (Hamilton, Ontario) from January 2001 to January 2002 were considered for inclusion into the present study. Information was collected during hospitalization and by chart review.

RESULTS:

Data from 217 patients were used. The mean (± SD) age of participants was 68.6±11.9 years, and 41% were women. The primary reason for admission to hospital was peripheral artery bypass surgery (67%). Of these patients, 79% were current smokers or had a prior history of tobacco use, 60% had at least two cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, cholesterol, diabetes or smoking) and 45% had undergone prior peripheral artery bypass surgery, amputation or carotid endarterectomy. Three-quarters of the patients had established coronary or cerebrovascular disease, or at least two cardiovascular risk factors. At the time of discharge, of those patients eligible for medical therapies, 16% did not receive antiplatelet or anticoagulant agents, 69% did not receive statins, 48% did not receive ACEIs and 49% did not receive beta-blockers.

CONCLUSIONS:

Patients with PAD represent a high-risk group in which more than 75% have established coronary or cerebrovascular disease, or multiple cardiovascular risk factors. Although the use of antiplatelet agents is common, the use of statins, ACEIs and beta-blockers may be improved.

Keywords: Medications, Peripheral arterial disease, Practice patterns

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Les patients atteints d’une artériopathie des membres inférieurs font partie du groupe à plus haut risque vasculaire d’infarctus du myocarde fatal et non fatal et d’accident vasculaire cérébral (AVC) et ont toujours été sous-traités d’un point de vue médical. D’après des données probantes récentes, l’incidence de décès cardiovasculaire, d’infarctus du myocarde et d’AVC pourrait être réduite de manière significative chez les patients atteints d’une artériopathie s’ils recevaient une thérapie antiplaquettaire, des inhibiteurs de la réductase de la coenzyme A 3-hydroxy-3-méthylglutaryl (statines), des inhibiteurs de l’enzyme de conversion de l’angiotensine (IECA) et dans certains cas, des bêta-bloquants.

OBJECTIFS :

Caractériser les modèles de thérapie médicale en pratique (antiplaquettaires, statines, IECA et bêta-bloquants) chez les patients atteints d’une artériopathie admis dans un hôpital de soins tertiaires et les lacunes de soins définis comme la proportion de patients qui n’avaient pas reçu de traitement parmi ceux qui y étaient admissibles.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

On a envisagé d’inclure dans la présente étude les patients atteints d’une artériopathie (code de Classification internationale de maladie 440,2) hospitalisés au Hamilton General Hospital de Hamilton, en Ontario, entre janvier 2001 et janvier 2002. On a colligé l’information pendant l’hospitalisation et par l’examen des dossiers.

RÉSULTATS :

On a utilisé les données de 217 patients. L’âge moyen (±ÉT) des participants était de 68,6±11,9 ans, dont 41 % étaient des femmes. La raison principale d’hospitalisation était un pontage artériel périphérique (67 %). De ce nombre, 79 % étaient fumeurs ou avaient déjà fumé, 60 % présentaient au moins deux facteurs de risque de maladie cardiovasculaire (hypertension, cholestérol, diabète ou tabagisme) et 45 % avaient déjà subi un pontage artériel périphérique, une amputation ou une endartériectomie carotidienne. Les trois quarts des patients étaient atteints d’une maladie coronaire ou cérébrovasculaire établie ou présentaient au moins deux facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire. Au moment du congé, parmi les patients admissibles à une thérapie médicale, 16 % n’avaient pas reçu d’antiplaquettaires ou d’anticoagulants, 69 % n’avaient pas reçu de statines, 48 % n’avaient pas reçu d’IECA et 49 % n’avaient pas reçu de bêta-bloquants.

CONCLUSIONS :

Les patients atteints d’une artériopathie font partie d’un groupe très vulnérable dont plus de 75 % souffrent d’une maladie coronarienne ou cérébrovasculaire établie ou présentent de multiples facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire. Bien que le recours aux antiplaquettaires soit courant, l’utilisation de statines, d’IECA et de bêta-bloquants pourrait augmenter.

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is atherosclerotic vascular disease affecting the lower extremities, which leads to estimated 10% of persons older than 70 years of age have symptomatic intermittent claudication, and more than 50% have asymptomatic PAD (1–3). The primary determinants of PAD are similar to the risk factors for coronary atherosclerosis, and the strongest risk factors include tobacco exposure (OR=4.0), diabetes (OR=2.6), elevated blood pressure (OR=2.0) and dyslipidemia (OR=1.3) (4–6). Patients with symptomatic PAD have a threefold increase in the rate of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke and cardiovascular death (3,7–9), and patients with asymptomatic PAD (defined as a low ankle-brachial index without symptoms) have a 1.5- to twofold increase in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (8). Patients with PAD of the extremities suffer a high incidence of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular disease (CVD) and have been traditionally undertreated from a medical perspective; historically, they have been sent for surgical assessment only, with little consideration from the medical standpoint (10). Recent evidence suggests that the incidence of cardiovascular death, MI and stroke among PAD patients may be reduced by 25% if antiplatelet therapy is used, by 25% if 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins) are used and by 25% when angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) are used (11–13). Furthermore, because the majority of PAD patients have concomitant coronary artery disease, they may benefit from treatment with beta-blockers, which are indicated for patients with a history of MI, congestive heart failure or angina (14,15).

In a recent study we conducted among hospitalized patients with PAD (16), we observed that fewer than one-half of all patients were discharged on any antithrombotic therapy, and an even smaller percentage were sent home on other cardiac medications. However, the factors contributing to the apparent suboptimal use of these life-saving medications are unclear, and they may be related to the lack of awareness of their potential benefit, the retrospective nature of our data collection and/or the presence of major contraindications, leading to an appropriate lack of medical therapy of a certain class or classes of medication. To address some of these shortcomings in our previous report (16), the objective of the present study was to characterize the practice pattern of the use of antiplatelet therapy, statins, ACEIs and beta-blockers among PAD patients admitted to a tertiary care hospital for PAD symptoms or a planned interventional procedure, and to determine the ‘care gap’ – defined as the percentage of patients who were eligible for treatment (ie, having no major contraindications), but who did not receive antiplatelet, statin, ACEI or beta-blocker therapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Institutional review board approval was obtained for this project in April 2000.

Study population

Consecutive PAD patients (International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision [17], code 440.2) who were admitted to the Hamilton General Hospital in Hamilton, Ontario, from January 2001 to January 2002 (inclusive) were included in the present analysis.

Data abstraction

A standardized data collection form was developed, and data were abstracted during the index hospitalization. Information was collected on demographic characteristics, reason(s) for admission, in-hospital procedures or complications, medications (on admission, in hospital and on discharge), past medical history and length of stay.

All patients were evaluated for the presence of major contraindications to four classes of life-saving medications. Major contraindications included all absolute contraindications cited in the Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties (18), and the Micromedex database (19) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Major contraindications for each class of medication

| Medication class | Contraindication |

|---|---|

| Antithrombotic therapy* | Hypersensitivity, bleeding ulcer, thrombocytopenia, hemophilia or a bleeding disorder, hemorrhagic state, alcohol use or abuse |

| Statins | Hypersensitivity, active liver disease, unexplained or persistent elevation of serum transaminases, marked elevation of creatine phosphokinase, myopathy, rhabdomyolysis |

| ACEIs | Hypersensitivity, angioedema, renal insufficiency, renal artery stenosis |

| Beta-blockers | Hypersensitivity, second- or third-degree heart block, overt cardiac failure, moderate or severe congestive heart failure, severe sinus bradycardia, cardiogenic shock, a systolic blood pressure of less than 100 mmHg, myocardial infarction in patient with heart rate of less than 45 beats/min, bronchial asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sick sinus syndrome |

Antithrombotic therapy includes antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant therapy. ACEI Angiotensin-converting enzyme inihibitor

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables such as age were summarized as means, and as categorical variables were summarized as proportions; 95% CI were also calculated. All analyses were conducted using ACCESS (Microsoft Corp, USA) and SPSS software (version 10.1, SPSS Inc, USA).

RESULTS

Demographic profile and risk factors

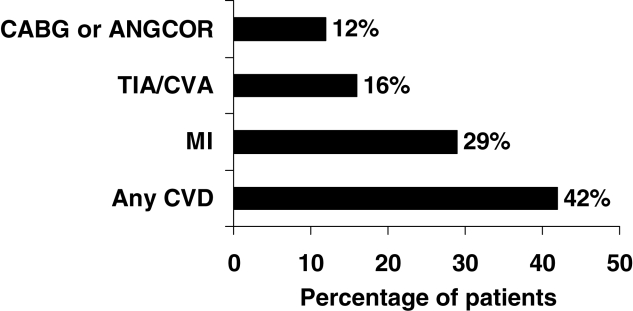

In the present study, 221 patients were identified during their index hospitalization. Four patients were excluded because two patient charts could not be found after discharge and two patients died during their hospital stay. The mean (± SD) age of all patients was 68.6±11.9 years, and 41% were women. The mean (± SD) length of stay was 11±18 days. Of these patients, 42% (95% CI 36% to 49%) had established coronary or cerebrovascular disease (ie, history of MI, stroke, coronary artery bypass graft, coronary angioplasty), 29% (95% CI 23% to 35%) suffered a previous MI, 16% (95% CI 11% to 21%) suffered a prior stroke and 12% (95% CI 8% to 17%) had a previous coronary artery bypass graft or previous coronary angioplasty (Table 1). The majority of patients (93%; 95% CI 88% to 95%) had at least one major CVD risk factor (diabetes, hypertension, elevated cholesterol or history of smoking). More specifically, 79% of patients (95% CI 72% to 84%) were current or former cigarette smokers, 57% (95% CI 50% to 63%) suffered from hypertension requiring treatment, 34% (95% CI 28% to 41%) experienced high cholesterol and 35% (95% CI 29% to 42%) had diabetes requiring medical treatment. Also, 60% of patients had at least two of the aforementioned cardiovascular risk factors, and more than three-quarters of patients had either established coronary or cerebrovascular disease, or at least two cardiovascular risk factors (Figure 1). A small number of individuals (3%; 95% CI 2% to 7%) did not have a history of established CVD or a CVD risk factor (Table 2).

Figure 1).

History of coronary and cerebrovascular disease in 217 patients with peripheral vascular disease at a tertiary care hospital in Ontario between 2001 and 2002. Individual risk factors and clinical history categories are not mutually exclusive. ANGCOR Coronary angioplasty; CABG Coronary artery bypass graft; CVA Cerebrovascular accident; CVD Cardiovascular disease; MI Myocardial infarction; TIA Transient ischemic attack

TABLE 2.

General characteristics of patients with peripheral artery disease at a tertiary care hospital in Ontario, 2001 to 2002 (n=217)

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 68.6 (11.9) |

| Female, % | 41 |

| Mean length of stay, days (SD) | 11 (18) |

| History of MI, % | 29 |

| History of PTCA or CABG, % | 12 |

| History of previous MI, prior PTCA or CABG, % | 42 |

| History of prior stroke, % | 16 |

| History of cardiovascular disease*, % | 42 |

| Current smoker, % | 28 |

| Former smoker, % | 51 |

| Diabetes on treatment, % | 35 |

| Hypertension on treatment, % | 57 |

| Elevated cholesterol†, % | 34 |

| Any cardiovascular disease risk factor, % | 93 |

| ≥2 cardiovascular disease risk factors, % | 60 |

| Established coronary or cerebrovascular disease, or ≥2 cardiovascular disease risk factors, % | 76 |

Cardiovascular disease is defined as prior history of coronary or cerebrovascular disease;

Based on a history of elevated cholesterol recorded in the chart. CABG Coronary artery bypass graft; MI Myocardial infarction; PTCA Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty

Forty-five per cent of all patients (95% CI 38% to 51%) had undergone prior peripheral artery bypass graft surgery, peripheral angioplasty (12%; 95% CI 9% to 18%), limb amputation (6.5%; 95% CI 4% to 10.5%) or carotid endarterectomy (4%; 95% CI 2% to 8%).

Procedures in hospital

The primary reason for hospitalization was for peripheral artery bypass surgery (67%; 95% CI 60% to 73%). Other reasons for admission included management of acute limb ischemia (10%; 95% CI 7% to 15%), worsening limb claudication (9%; 95% CI 6% to 13%), peripheral angioplasty (7%; 95% CI 4% to 11%), limb amputation (6%; 95% CI 4% to 10%), thrombolysis (0.5%; 95% CI 0% to 3%) and infection requiring antibiotics (0.5%; 95% CI 0% to 3%).

Patterns of drug use

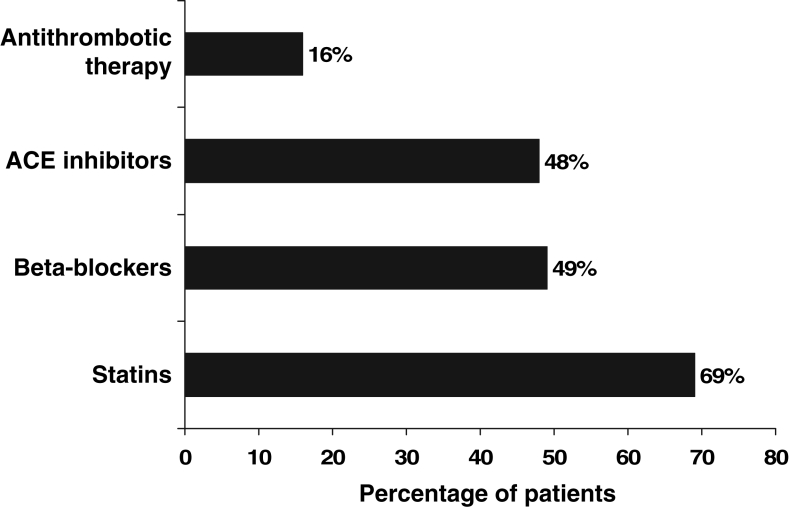

On admission, 59.4% of patients were on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy, 31% were taking statins, 42% were taking ACEIs and 29% reported taking beta-blockers. After a review of contraindications, 95% of patients (206 of 217) were deemed eligible for antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy. Eighty-four per cent of these patients (173 of 206) were discharged home on antiplatelet therapy (n=160) or anticoagulant therapy (n=13), yielding a care gap of 16%. Eleven patients were ineligible because of hypersensitivity (n=2), bleeding ulcer (n=2), thrombocytopenia (n=1), bleeding disorder (n=2), hemorrhagic state (n=2) and alcohol abuse (n=2). And while 96% (209 of 217) of patients were eligible for therapy with statins, only 31% of these patients (65 of 209) were discharged home on this medication, yielding a care gap of 69%. Eight patients were not eligible for therapy because of active liver disease (n=4), a significant rise in transaminases (n=1), a significant rise in creatine phosphokinase (n=1), rhabdomyolysis (n=1) and current fibrate therapy for hypercholesterolemia (n=1). Ninety-two per cent (199 of 217) of patients were eligible for therapy with ACEIs, and only 52% (104 of 199) received this therapy on discharge, with an associated care gap of 48%. Of these patients, 18 were ineligible because of renal insufficiency (n=16), hypersensitivity (n=1) and renal artery stenosis (n=1). Although fewer patients were eligible for beta-blockers (80%; 174 of 217), only 51% (89 of 174) received them on discharge. The care gap for beta-blockers was 49%. Additionally, 43 patients were ineligible because of asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n=32), hypotension with a systolic blood pressure of less than 100 mmHg (n=7), moderate or severe congestive heart failure (n=2), second- or third-degree heart block (n=1) and overt cardiac failure (n=1) (Table 3, Figure 2).

TABLE 3.

Care gap for each class of life-saving medication for patients with peripheral artery disease at a tertiary care hospital in Ontario, 2001 to 2002 (n=217)

| Discharge medication | Patients receiving drug on admission n (%) | Patients eligible for therapy n (%) | Patients receiving drug at discharge n (%) | Care gap, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antithrombotic therapy* | 129 (59.4) | 206 (95)† | 173 (84) | 16 |

| Statin | 68 (31.3) | 209 (96) | 65 (31) | 69 |

| ACEI | 91 (41.9) | 199 (92) | 104 (52) | 48 |

| Beta-blocker | 64 (29.5) | 174 (80) | 89 (51) | 49 |

Antithrombotic therapy includes antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant therapy;

A reminder system for clinicians to consider antithrombotic therapy was implemented before the present study and accounts for the increase in use at discharge. ACEI Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

Figure 2).

Care gap for each class of life-saving medication for 217 patients with peripheral artery disease at a tertiary care hospital in Ontario between 2001 and 2002. Antithrombotic therapy includes antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant therapy. ACE Angiotensin-converting enzyme

DISCUSSION

Patients admitted with PAD represented a high-risk group, because more than 75% of patients had established coronary or cerebrovascular disease, or the presence of two or more cardiovascular risk factors. A significant care gap exists for life-saving medications among patients with PAD. Specifically, the care gaps for antithrombotic therapy, statins, ACEIs and beta-blockers were 16%, 69%, 48% and 49%, respectively (Figure 2).

We identified that close to 80% of our patients had current or prior exposure to tobacco. Tobacco exposure is the strongest determinant of PAD, and is associated with a significantly reduced survival and lower graft patency (9,20). Although smoking is a major risk factor, clinicians need to recognize that it is also an addiction, which will require a sustained effort to aid patients who have this condition. In accordance with proven strategies to alter smoking habits, physicians should repeatedly advise their patients during clinical encounters, and patients should be referred to a formal smoking cessation program that offers counselling and pharmacological aids (21–23).

Clinical trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of antiplatelet therapy, statins, ACEIs and beta-blockers in patients with PAD (11–14). Indeed, each class of these medications has been shown to lower the risk of future vascular events by approximately one-quarter each in high-risk patients. It is likely that their effects are independent and additive, and collectively, they may have the potential to reduce recurrent cardiovascular events by at least 50% (24). Aggressive medical therapy, combined with cessation of tobacco use, may push the potential risk reduction of future cardiovascular events closer to 75%.

Our results are consistent with recent reports from Canada (25,26), the United States and Europe (27,28), and indicate that PAD patients are undertreated with medical therapies. To address the care gap in life-saving medications among PAD patients, certain strategies should be considered or implemented. First, it is important to increase the awareness of the high-risk nature of PAD patients among both physicians and allied health care professionals through continuing education sessions and medical literature. A second strategy consists of a care delivery model in which surgeons and medical specialists work closely together to ensure PAD patients are considered for specific medical therapies preoperatively during hospitalization or shortly after hospital discharge. In a prior retrospective study (16), we reported that fewer than one-half of PAD patients discharged from our institution were sent home on antithrombotic therapy (48.7%). However, with the implementation of a reminder system, which involved a discussion on discharge planning between a nurse-clinician and the responsible physician, the rate of antithrombotic therapy at discharge improved significantly to 86% (29). This approach was supported by Lappe et al (30), who developed and implemented a discharge medication program to ensure appropriate prescription of acetylsalicylic acid, statins, beta-blockers, ACEIs and warfarin in patients with CVD. These researchers compared medication discharge rates before and after implementation of the discharge medication program. By one year, the rate of prescription of each medication increased significantly to more than 90% (P<0.001).

Study limitations

The data described in the present study are based on a review of charts of PAD patients hospitalized in a single tertiary care hospital and may not subsequently be generalized. Consecutive patients were identified during a set time period to minimize selection bias. The care gap may have been overestimated if major contraindications to the studied medical therapies were not recorded on the chart, or if patients were prescribed or resumed medications after hospital discharge. However, this possibility is not supported by the low use of these medications at admission and data from other studies, which suggests that PAD patients are undertreated.

CONCLUSIONS

A substantial proportion of patients admitted with PAD have a history of established CVD, justifying the aggressive use of life-saving medical therapies. The care gap for antiplatelet therapy was reduced at our institution after the implementation of a reminder system at the time of discharge. The care gaps for statins, ACEIs and beta-blockers remain substantial, and may be improved by similar reminder systems.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: S Anand holds a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Clinician-Scientist Phase 2 Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reeder B, Liu L, Horlick L. Sociodemographic variation in the prevalence of cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 1996;12:271–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDaniel MD, Cronenwett JL. Basic data related to the natural history of intermittent claudication. Ann Vasc Surg. 1989;3:273–7. doi: 10.1016/S0890-5096(07)60040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Criqui MH, Fronek A, Barrett-Connor E, Klauber MR, Gabriel S, Goodman D. The prevalence of peripheral artery disease in a defined population. Circulation. 1985;71:510–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.71.3.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murabito J, D’Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Wilson WF. Intermittent claudication. A risk profile from The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1997;96:44–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zelis R, Mason DT, Braunwald E, Levy RI. Effects of hyperlipoproteinemias and their treatment on the peripheral circulation. J Clin Invest. 1970;49:1007–15. doi: 10.1172/JCI106300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couch NP. On the arterial consequences of smoking. J Vasc Surg. 1986;3:807–12. doi: 10.1067/mva.1986.avs0030807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reunanen A, Takkunen H, Aromaa A. Prevalence of intermittent claudication and its effect on mortality. Acta Med Scand. 1982;211:249–56. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1982.tb01939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doobay AV, Anand SS. Sensitivity and specificity of the ankle-brachial index to predict future cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1463–9. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000168911.78624.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dagenais GR, Maurice S, Robitaille NM, Gingras S, Lupien PJ. Intermittent claudication in Quebec men from 1974–1986: The Quebec Cardiovascular Study. Clin Invest Med. 1991;14:93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hackam DG, Goodman SG, Anand SS. Management of risk in peripheral artery disease: Recent therapeutic advances. Am Heart J. 2005;150:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy – 1: Prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration BMJ 199430881–106.(Erratum in 1994;308:1540) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:7–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G.Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators N Engl J Med 2000342145–53.(Errata in 2000;342:748, 2000;342:1376) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Randomised trial of intravenous atenolol among 16 027 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-1. First International Study of Infarct Survival Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1986;2:57–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuyuki RT, Teo KK, Ikuta RM, Bay KS, Greenwood PV, Montague TJ. Mortality risk and patterns of practice in 2,070 patients with acute myocardial infarction, 1987–92. Relative importance of age, sex, and medical therapy. Chest. 1994;105:1687–92. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.6.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anand SS, Kundi A, Eikelboom J, Yusuf S. Low rates of preventive practices in patients with peripheral vascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 1999;15:1259–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases, Ninth RevisionVolumes 1 and 2Geneva: 1977–78 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canadian Pharmacists Association . Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties. Ottawa: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomson Micromedex Healthcare Series, version 5.1. Greenwood Village: Thomson Micromedex; [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pechacek T, Asma S, Eriksen M. Tobacco: Global burden and community solutions. In: Yusuf S, Cairns JA, Camm AJ, Fallen EL, Gersh BJ, editors. Evidence Based Cardiology. London: BMJ Books; 1998. pp. 165–78. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katz DA, Muehlenbruch DR, Brown RL, Fiore MC, Baker TB, AHRQ Smoking Cessation Guideline Study Group Effectiveness of implementing the agency for healthcare research and quality smoking cessation clinical practice guidelines: A randomized, controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:594–603. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manfredi C, Crittenden KS, Cho YI, Gao S. Long-term effects (up to 18 months) of a smoking cessation program among women smokers in public health clinics. Prev Med. 2004;38:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu SH, Anderson CM, Tedeschi GJ, et al. Evidence of real-world effectiveness of a telephone quitline for smokers. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1087–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yusuf S. Two decades of progress in preventing vascular disease. Lancet. 2002;360:2–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09358-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Omran M, Lindsay TF. Should all patients with peripheral arterial disease be treated with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor? Can J Cardiol. 2005;21:189–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown LC, Johnson JA, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, McAlister FA. Evidence of suboptimal management of cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and symptomatic atherosclerosis. CMAJ. 2004;171:1189–92. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okaa RK, Umoh E, Szuba A, Giacomini JC, Cooke JP. Suboptimal intensity of risk factor modification in PAD. Vasc Med. 2005;10:91–6. doi: 10.1191/1358863x05vm611oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lange S, Diehm C, Darius H, et al. High prevalence of peripheral arterial disease and low treatment rates in elderly primary care patients with diabetes. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2004;112:566–73. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-830408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anand S, Cina C, Harrsion L, et al. Improving the medical management of peripheral artery disease patients – a high-risk and undertreated group Can J Cardiol 200117Suppl C206B(Abst)11223492 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lappe J, Muhlestein J, Lappe D, et al. Improvements in 1-year cardiovascular clinical outcomes associated with a hospital-based discharge program. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:446–53. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-6-200409210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]