Abstract

A 67-year-old woman who presented with acute chest pain is reported. Three days before admission, she suffered from a flu-like infection. Coronary angiography showed no coronary stenosis. Ventriculography showed moderately reduced left ventricular function characterized by the so-called ‘apical ballooning’. Endomyocardial biopsies and polymerase chain reaction analysis of the plasma revealed an acute infection with human herpesvirus 6 subtype A. Histological and immunohistochemical analyses revealed myocarditis with areas of interstitial macrophages and fibrosis. The present case report links, for the first time, myocarditis with a human herpesvirus 6 subtype A infection and the appearance of apical ballooning.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndrome, Apical ballooning, HHV-6A, Myocarditis

Abstract

On présente le cas d’une femme de 67 ans qui a consulté pour des douleurs thoraciques aiguës. Trois jours avant son hospitalisation, elle avait souffert d’une infection pseudogrippale. La coronarographie n’a pas révélé de sténose coronarienne. La ventriculographie a démontré une légère réduction de la fonction ventriculaire gauche caractérisée par ce qu’on appelle un « ballonnement apical ». Les biopsies endomyocardiques et l’analyse des réactions en chaîne de la polymérase du plasma ont révélé une infection aiguë par le sous-type A de l’herpèsvirus humain de type 6, et les analyses histologique et immunohistochimique, une myocardite avec des zones de macrophages interstitiels et de fibrose. Le présent rapport de cas relie pour la première fois la myocardidte à une infection par le sous-type A de l’herpèsvirus humain de type 6 et l’apparition d’un ballonnement apical.

The etiology of myocarditis is still unclear; however, in most cases, viruses, particularly entero- and adenoviruses, are found to be the common pathogenic agents.

Molecular pathological findings in endomyocardial biopsies of patients with clinical myocarditis most frequently reveal parvovirus B19 (PVB19), human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), enteroviruses and adenoviruses, and sometimes the Epstein-Barr virus and human cytomegalovirus (1). Serological studies, viral cultures and molecular biological investigations indicate that HHV-6 is a ubiquitous virus (seropositivity in adults is greater than 90%), and that it is associated with human disease in both normal and immunocompromised persons. In some individuals, HHV-6 is found integrated into the chromosomes, which results in a high viral load in the blood (2). Primary infection usually occurs in early childhood, presenting with the clinical syndrome of exanthema subitum characterized by high fever and a mild skin rash, and is occasionally complicated by seizures secondary to encephalitis. Reactivations are common in elderly persons and in the immunosuppressed, such as transplant recipients and AIDS patients. HHV-6 reactivation is also described in settings such as drug hypersensitivity (eg, codeine phosphate, ganciclovir, cyanamide, etc) (3–5). However, HHV-6 subtype A (HHV-6A) has not been etiologically linked to a specific disease (2,6), but was recently found to induce fever, skin rash and liver dysfunction in a patient after unrelated cord blood transplantation (7). A recent sequence analysis of HHV-6 infections in patients with left ventricular dysfunction exclusively detected HHV-6 subtype B, but not subtype A (1).

The present case report describes, for the first time, an HHV-6A-associated myocarditis. Additionally, left ventriculography showed ‘apical ballooning’ as a transient and reversible phenomenon.

CASE PRESENTATION

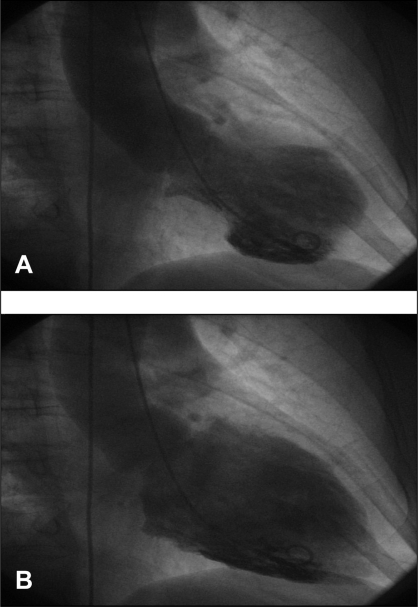

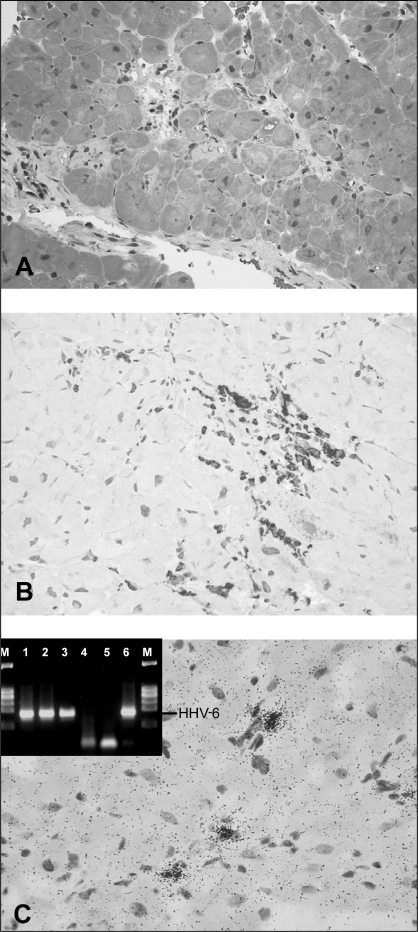

A 67-year-old woman experienced acute chest pain for the first time and was transferred to the University Hospital of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany, for coronary angiography. She had suffered from a flu-like infection three days before admission. There were no cardiovascular risk factors or predisposing factors for the reactivation of a viral infection or immunoincompetence. The patient had not taken any medication before arriving at the hospital and noted that she had been healthy until that day. An electrocardiogram showed ST abnormalities, and laboratory results showed elevated cardiac enzymes and signs of systemic inflammation (troponin I 24.2 μg/L, creatine kinase 475 U/L, creatine kinase (muscle-brain) 69 U/L, leukocytes 12×109/L, C-reactive protein 0.96×101 mg/L). Her heart rate and blood pressure were normal (72 beats/min, 115/80 mmHg). A coronary angiogram performed immediately on admission revealed normal coronary arteries. However, a ventriculogram showed moderately reduced left ventricular function characterized by apical ballooning (Figure 1). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of plasma and endomyocardial biopsies (obtained 14 days after hospital admission) gave proof of an acute HHV-6 infection, showing high viral loads in all materials investigated (Figure 2A). Direct DNA sequencing of HHV-6-positive PCR products confirmed the specificity of the PCR results and identified the HHV-6A subtype. Endomyocardial biopsies, peripheral blood leukocytes and plasma of the patient revealed negative PCR results for the presence of entero- and adenoviruses, PVB19, the Epstein-Barr virus, human cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus 1/2. Histological and immunohistochemical analysis of the endomyocardial biopsies revealed healing myocarditis with infiltrates of CD68+ macrophages and distinct interstitial fibrosis (Figures 2A and B). In situ hybridization showed the presence of HHV-6 genomes in interstitial mononuclear cells (Figure 2C).

Figure 1).

Left ventriculogram with apical ballooning. A Systolic; B Diastolic

Figure 2).

On the basis of Masson trichrome stains (A) and immunohistochemical detection of CD68+ macrophages (B), healing myocarditis was diagnosed in the patient. Interestingly, no CD3+ T lymphocytes were present at this stage of disease. A significant part of the myocardium revealed fibrosis (light gray-stained tissue). Visualization of the human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) DNA in interstitial mononuclear cells of the myocardium as detected by radioactive RNA/DNA in situ hybridization (C). Inset shows the detection of HHV-6 DNA by nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in endomyocardial biopsies (lane 1), peripheral blood leukocyte preparation (lane 2) and plasma (lane 3) of the patient. Control PCRs are shown in lanes 4 to 6 (HHV-6-negative patient [lane 4], PCR without DNA [lane 5] and HHV-6-positive control [lane 6]). M Marker (φX174 Hae III)

The patient received conventional medication for heart failure, including an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, a beta-blocker and a loop diuretic. Specific antiviral therapy was not initiated. During a scheduled follow-up in the outpatient clinic three weeks after discharge, a cardiac ultrasound showed normalization of left ventricular function without abnormalities of regional wall movement. An electrocardiogram at that time revealed T-wave inversion, but laboratory results were normal. Additionally, as expected, the viral load in the blood decreased, especially in the plasma, where the HHV-6 genomes could be detected only by nested PCR methods.

DISCUSSION

The present case report describes two phenomena: transient, reversible, left ventricular apical ballooning and an acute HHV-6A infection in a patient with healing myocarditis. Apical ballooning was originally described in 1990 and has predominantly been seen in Japan; it resembled an acute myocardial infarction (8). The onset is marked by ST elevation and increased levels of cardiac enzymes, and no pathological findings on coronary angiography, but with typical dyskinesis of the cardiac apex. Because endomyocardial biopsies infrequently give proof of virus infection and inflammation, Bybee et al (9) dismissed a myocarditis association, whereas Japanese research groups repeatedly reported focal myocytolysis, cellular infiltrates and interstitial fibrosis, indicating that apical ballooning is associated with cardiac inflammation (10,11). In most cases of myocarditis, viruses are found as pathogenic agents. Recent analysis of viral genomic sequences in endomyocardial biopsies frequently detected PVB19 and HHV-6, but exclusively HHV-6 subtype B (1). To our knowledge, HHV-6A infection has not before been associated with myocarditis. Thus, the present report challenges the common dictum that HHV-6A is clinically unrelated to myocarditis (6). Most recent reports of immunosup-pressed patients consistently indicate that lymphadenopathy, some neurological diseases and liver dysfunction can be caused by HHV-6A (7,12–14). HHV-6A also has an increased neurovirulence compared with subtype B. Furthermore, HHV-6A is neurotropic, but it can also infect lymphocytes, monocytes and other cell lines (15). HHV-6 has been shown to upregulate the production of the proinflammatory CC chemokine regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (16), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and interleukin-8 (17), which lead to attraction of immunocompetent cells and the development of inflammatory processes, and via these interactions, HHV-6 may contribute to the development of myocarditis.

CONCLUSION

The peculiar phenomenon of apical ballooning remains controversial, but it can be seen in relation to clinically suspected (sub)acute myocarditis.

The present report is the first to document a cardiac HHV-6A infection that meets the histological and immunohistochemical criteria of myocarditis sufficiently enough to be considered the causative agent for apical ballooning. Further molecular pathological studies are required to identify mechanisms by which HHV-6 may contribute to the development of myocarditis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kühl U, Pauschinger M, Noutsias M, et al. High prevalence of viral genomes and multiple viral infections in the myocardium of adults with “idiopathic” left ventricular dysfuntion. Circulation. 2005;111:887–93. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155616.07901.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward KN. The natural history and laboratory diagnosis of human herpesviruses-6 and -7 infections in the immunocompetent. J Clin Virol. 2005;32:183–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enomoto M, Ochi M, Teramae K, Kamo R, Taguchi S, Yamanae T. Codein phosphate-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:799–802. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnbaum T, Padovan CS, Sporer B, et al. Severe meningoencephalitis caused by human herpesvirus 6 subtype B in an immunocompetent woman treated with ganciclovir. Clin Inf Dis. 2005;40:887–9. doi: 10.1086/427943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitani N, Aihara M, Yamakawa Y, et al. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome due to cyanamide associated with multiple reactivation of human herpesviruses. J Med Virol. 2005;75:430–4. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Bolle L, Naesens L, De Clercq E. Update on human herpesvirus 6 biology, clinical features, and therapy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:217–45. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.1.217-245.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomonari A, Takahashi S, Ooi J, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 variant A infection with fever, skin rash, and liver dysfunction in a patient after unrelated cord blood transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36:1109–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato H, Tateishi H, Uchida T, Dote K, Ishihara M. Tako-tsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction due to multivessel coronary spasm. In: Kodama K, Haze K, Hori M, editors. Clinical Aspect of Myocardial Injury: From Ischemia to Heart Failure. Tokyo: Kagakuhyoronsha Publishing Co; 1990. pp. 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, et al. Systematic review: Transient left ventricular apical ballooning: A syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:858–65. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurisu S, Sato H, Kawagoe T, et al. Tako-tsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction with ST-segment elevation: A novel cardiac syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2002;143:448–55. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.120403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abe Y, Kondo M. Apical ballooning of the left ventricle: A distinct entity? Heart. 2003;89:974–6. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.9.974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freitas RB, Freitas MR, Linhares AC. Evidence of active herpesvirus 6 (variant-A) infection in patients with lymphadenopathy in Belem, Para, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2003;45:283–8. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652003000500008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borghi E, Pagani E, Mancuso R, et al. Detection of herpesvirus-6A in a case of subacute cerebellitis and myoclonic dystonia. J Med Virol. 2005;75:427–9. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stodberg T, Deniz Y, Esteitie N, et al. A case of diffuse ptomeningeal oligodendrogliomatosis associated with HHV-6 variant A. Neuropediatrics. 2002;33:266–70. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-36739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mori Y, Seya T, Huang HL, Akkapaiboon P, Dhepakson P, Yamanishi K. Human herpesvirus 6 variant A but not variant B induces fusion from without in a variety of human cells through a human herpesvirus 6 entry receptor, CD46. J Virol. 2002;76:6750–61. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6750-6761.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grivel JC, Santoro F, Chen S, et al. Pathogenic effects of human herpesvirus 6 in human lymphoid tissue ex vivo. J Virol. 2003;77:8280–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.15.8280-8289.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caruso A, Rotola A, Comar M, et al. HHV-6 infects human aortic and heart microvascular endothelial cells, increasing their ability to secrete proinflammatory chemokines. J Med Virol. 2002;67:528–33. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]