Abstract

There is growing recognition of the public-health burden of intimate partner violence (IPV) and the potential for the health sector to identify and support abused women. Drawing upon models of health-sector integration, this paper reviews current initiatives to integrate responses to IPV into the health sector in low- and middle-income settings.

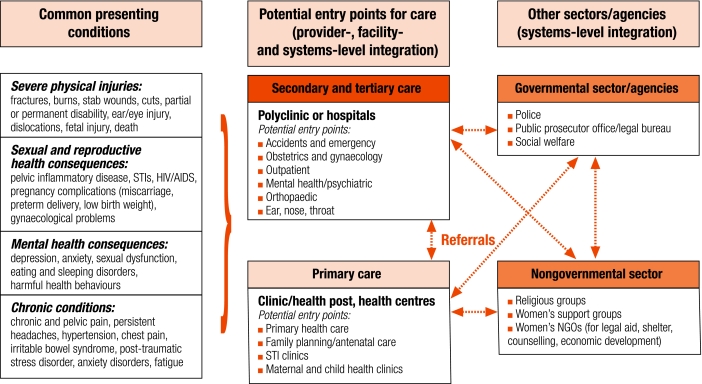

We present a broad framework for the opportunities for integration and associated service and referral needs, and then summarize current promising initiatives. The findings suggest that a few models of integration are being replicated in many settings. These often focus on service provision at a secondary or tertiary level through accident and emergency or women’s health services, or at a primary level through reproductive or family-planning health services. Challenges to integration still exist at all levels, from individual service providers’ attitudes and lack of knowledge about violence to managerial and health systems’ challenges such as insufficient staff training, no clear policies on IPV, and lack of coordination among various actors and departments involved in planning integrated services. Furthermore, given the variety of locations where women may present and the range and potential severity of presenting health problems, there is an urgent need for coherent, effective referral within the health sector, and the need for strong local partnership to facilitate effective referral to external, non-health services.

Résumé

La charge pour la santé publique résultant des violences exercées par les partenaires intimes, ainsi que les possibilités pour le secteur sanitaire d’identifier et de soutenir les femmes maltraitées, sont de plus en plus reconnues. A partir de modèles d’intégration dans le secteur sanitaire, le présent article examine les initiatives actuelles pour intégrer au secteur de la santé les réponses à cette violence dans les pays à revenu faible ou moyen.

Nous présentons dans leurs grandes lignes les possibilités d’intégration, les services associés et les besoins en structures spécialisées, puis nous donnons un résumé des initiatives actuelles prometteuses. Les résultats laissent à penser qu’un petit nombre de modèles d’intégration sont reproduits dans de nombreux pays. Ces modèles sont souvent axés sur la prestation de services au niveau tertiaire ou secondaire par le biais de structures spécialisées dans les accidents, les situations d’urgence ou la santé des femmes, ou encore au niveau primaire par l’intermédiaire d’unités de santé reproductive ou de planification familiale. Cette intégration se heurte encore à des difficultés à tous les niveaux, allant de la mentalité et du manque de connaissances à propos de la violence du prestateur de services individuel à des problèmes affectant l’encadrement et les systèmes de santé, tels que le manque de personnel formé, l’absence de politiques claires sur les violences exercées par les partenaires intimes et l’insuffisance de la coordination entre les divers acteurs et départements intervenant dans la planification de services intégrés. En outre, compte tenu de la diversité des lieux où se trouvent femmes, ainsi que de la variété et de la gravité potentielle des problèmes de santé qui peuvent se poser, il est urgent de disposer au sein du secteur de la santé d’un dispositif d’orientation vers des services spécialisées cohérent et efficace et il faut qu’un partenariat local solide facilite une orientation efficiente vers des services spécialisés externes, non sanitaires.

Resumen

Se está cobrando conciencia cada vez más del problema de salud pública que supone la violencia de pareja (VP) y del potencial del sector sanitario para identificar y apoyar a las mujeres maltratadas. Basándose en modelos de integración del sector de la salud, este artículo analiza las iniciativas emprendidas actualmente para integrar las respuestas a la VP en dicho sector en los entornos de ingresos bajos y medios.

Presentamos un marco amplio donde inscribir las oportunidades de integración y las necesidades de servicios y derivación asociadas, para resumir luego las iniciativas más prometedoras del momento. Los resultados parecen indicar que hay unos cuantos modelos de integración que están repitiéndose en muchos entornos. Dichos modelos se centran a menudo en la prestación de servicios en los niveles secundario o terciario a través de los servicios de urgencias, atención a accidentados o salud de la mujer, o en el nivel primario a través de los servicios de salud reproductiva y planificación familiar. La integración sigue encontrando dificultades a todos los niveles, desde la actitud de algunos proveedores de servicios y su falta de conocimientos sobre la violencia hasta problemas de tipo gerencial y relacionados con los sistemas de salud como son una formación insuficiente del personal, la falta de políticas claras sobre la VP y la falta de coordinación entre los actores y departamentos implicados en la planificación de servicios integrados. Es más, dada la variedad de lugares a los que pueden acudir las mujeres, así como la diversidad y gravedad potencial de los problemas de salud que motivan la consultas, se necesita de forma urgente un sistema de derivación coherente y eficaz dentro del sector de la salud, así como fórmulas de colaboración local robustas que faciliten la derivación eficaz a servicios externos no relacionados con la salud.

ملخص

يتزايد حاليا إدراك العبء الصحي الناجم عن العنف الممارَس ضد الشريك الحميم، وإدراك قدرة القطاع الصحي على التعرف على المرأة ضحية ەذا العنف وتقديم الدعم لەا. وتستعرض ەذە الورقة المبادرات الحالية لإدماج الاستجابة للعنف الممارَس ضد الشريك الحميم في أنشطة القطاع الصحي في الأماكن المنخفضة الدخل والمتوسطة الدخل، باستخدام نماذج إدماج القطاع الصحي.

ويقدِّم الباحثون في ەذە الورقة إطاراً عريضاً للفُرَص المتاحة للإدماج وما يرتبط بذلك من احتياجات إلى خدمات وإحالة، ثم يعرضون بإيجاز المبادرات الحالية الواعدة. وتشير النتائج إلى أن عدداً قليلاً من نماذج الإدماج تتكرَّر في العديد من الأماكن. وعادةً ما تركِّز ەذە النماذج على تقديم الخدمات على المستوى الثانوي أو الثالثي (التخصصي) من خلال الخدمات الصحية في حالات الحوادث والطوارئ، أو المقدَّمة للمرأة، أو على مستوى أولي من خلال خدمات الصحة الإنجابية أو تنظيم الأسرة. ولاتزال ەناك تحدِّيات أمام عملية الإدماج على جميع المستويات، تشمل المواقف الفردية لمقدِّمي الخدمات، ونقص المعارف حول العنف، وتحدِّيات النُظُم الإدارية والصحية مثل عدم كفاية التدريب الذي يتلقَّاە العاملون، والافتقار إلى سياسات واضحة بشأن العنف الممارَس ضد الشريك الحميم، ونقص التنسيق بين مختلف الأطراف والإدارات المشاركة في تخطيط الخدمات المتكاملة. وبالنظر إلى تنوُّع الأماكن التي تتواجد فيەا المرأة والخطورة المحتملة المترتبة على عرض المشكلات الصحية، تمس الحاجة العاجلة إلى الإحالة المتَّسِقَة والفعَّالة داخل القطاع الصحي، وإلى شراكة محلية قوية لتيسير الإحالة الفعَّالة إلى المرافق الخارجية غير المختصَة بالصحة.

Introduction

Over the past 10 years, violence against women has become recognized as a serious public-health issue.1 Research, initially in North America and Europe, but increasingly from other settings, has helped demonstrate the high prevalence and wide range of health consequences of intimate partner violence (IPV). The WHO multicountry study on women’s health and domestic violence showed that the lifetime prevalence of physical or sexual partner violence, or both, varied between 15% and 71% in 10 countries.2 Abused women are more likely to have poorer health than women who have never been abused3 and may suffer health consequences of violence long after the abuse has ended.4 The physical health consequences include both injury and a broader range of impacts,4,5 including: (i) nutritional status, digestive problems and hypertension;6 (ii) sexual and reproductive health, including fertility, contraceptive use, and HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs); (iii) maternal health, including increased risk for high blood pressure, risk of antepartum haemorrhage and of miscarriage;7–9 and (iv) mental health, including risk of depression and suicide.10 IPV has also been shown to affect the health and well-being of children in violent families, e.g. by decreasing vaccination status and increasing the risk of behavioural and psychological problems.7,8

Need for health-sector responses

Given that IPV is an important risk factor for a range of health problems, there has been growing awareness of the need for health providers to be able to respond better to cases of violence that they encounter, and to help identify women experiencing violence and refer them to specialized services. This referral is very important, as many women experiencing violence will never seek help from a legal or stand-alone service, but will probably go to a health service during their adult life. Women may access the health system at a range of potential entry points for service provision and may have a range of presenting health needs. Some women experiencing partner violence will present at primary care,11,12 while women experiencing serious injuries may present to hospital emergency services.13–15 Given that coerced sex and violence in pregnancy is widespread, ante- and postnatal care, family planning or post-abortion care are also potentially important entry points.16–18 Therefore, it is important that the health sector ensures not only the efficient delivery of health-related services to victims of violence, but also facilitates these women’s access to non-health services.

Some women may disclose violence without being questioned, while others may not openly disclose the cause of their presenting problem. Much of the debate regarding the health-sector response has focused upon whether women should be “screened” for violence, and whether such interventions impact on women’s future risk of violence.19,20 There has been much less debate about what may be the most important entry points for health-sector involvement in different settings, or consideration of what may be the most feasible ways for health services in low- and middle-income countries to integrate responses to violence into the health sector.

After briefly summarizing the evolution of literature on integration and its integrated service models, this paper reviews promising health-sector responses to violence currently being integrated into existing services in low- and middle-income countries. We present a broad framework to help conceptualize the potential entry points for care, and the required systems of referral both within and outside the health sector. Challenges and opportunities, and future research priorities, are then discussed.

Models of service integration

Debates on “integration” of services, and what constitutes “integrated” services at different levels of the health system have been ongoing since the 1970s. During the 1980s a (somewhat false) dichotomy emerged between “selected” (issue-specific, more vertically organized) services and “comprehensive” (more linked or integrated) services. During the 1990s, much attention was given to expanding the remit of family-planning programmes to encompass a broader range of reproductive and sexual health services, notably the management of STIs, including HIV.21,22 Research focused on how providers, facilities and health systems (including policies and programmes guidelines) could – or should – respond to the challenge of adding, or integrating, new services into existing ones.

An extensive literature from various fields, but particularly sexual and reproductive health, highlights a range of issues associated with integration.21,23–27 What emerges is the lack of consensus on a definition, although “integrated services” tend to be equated at some level with the notion of “holistic” service delivery.27 In general, this literature describes integration at three different levels: at the level of the provider, the facility and the system. “Provider-level integration” means the same provider offers a range of services during the same consultation, e.g. a nurse in accident and emergency is trained and resourced to screen for domestic violence, treat her client’s injury, provide counselling and refer her to external sources of legal advice. “Facility-level integration” means a range of services is available at one facility but not necessarily from the same provider, e.g. a nurse in accident and emergency may be able to treat a woman’s injury, but may not be able to counsel a woman who discloses domestic violence, and may need instead to refer the woman to the hospital medical social worker for counselling. “Systems-level integration” means that there is a coherent referral system between facilities so that, for instance, a family-planning client who discloses violence can be referred to a different facility (possibly at a different level) for counselling and treatment. Unlike provider- and/or facility-level integration, which usually happen within the same site, system-level integration is multisite. Within the health sector, most services involve a combination of provider- and facility-level integration; full systems-level integration is rare.

Integration literature highlights challenges at each of the three levels. At the provider level, entrenched medical hierarchies may impede putting training on integrated service provision into practice.22 At the facility level, many issues have been identified, including poor management, shortage of personnel and supplies, lack of appropriate equipment for expanding services, and poor physical infrastructure.21–23,26 At a systems level, there is a lack of coordination among various actors and departments involved in planning integrated services, lack of clear guidelines for training staff, underfunding and poor, or no, legislative systems for supporting integration (e.g. if nurses are to be enabled to prescribe drugs for STI management, the law or health policy may require changing).21–24,27

Health-sector responses

For this paper, a detailed literature review of the published and grey literature (in English, French and Spanish) on promising health-sector interventions responding to violence in low- and middle-income countries between 1995 and 2005 was conducted. Sources of research evidence for the review included electronic bibliographic databases (African Healthline, Cochrane Library, ELDIS, Isis Web of knowledge, LILACS, Popline and PubMed®); web sites from key organizations/nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in the field; reference lists from primary and review articles; peer-reviewed journals, grey literature and conference proceedings. Programmes were selected based on the following criteria: (i) implemented between 1995 and 2005; (ii) focused specifically on health-service provision to address violence against women in developing countries; and (iii) where possible, being evaluated or measured.

The literature review identified 17 promising programmes that, after further appraisal, were reduced to nine: five programmes in central and Latin America, three in Asia and one in Africa.25,28–35 Of the nine models reviewed, seven were implemented in middle-income countries, and two in low-income countries. Four were implemented at a primary level, and five at secondary or tertiary level. Drawing on the integration models discussion above, these programmes have been characterized into three models of integration: (i) provider- and/or facility-level integration of selected services at the same site (i.e. a few selected services are integrated into existing services by the same provider and/or on one site); (ii) provider- and/or facility-level integration of comprehensive services at the same site (i.e. a wide range of services are integrated into existing services by the same provider and/or on the same site); and (iii) systems-level integration involving multisite linkage in addition to provider- and/or facility-level integration. Table 1 summarizes the programme models and they are discussed below.

Table 1. Summary of existing health-sector integration interventions in low- and middle-income countries and forms of integration adopted.

| Level of IPV service integration | Models of integration |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary level |

Secondary and tertiary level |

|||||

| Reproductive health | Primary health centre | Emergency department | Reproductive health | Mental health/counselling | ||

| Level 1: selective provider- and/or facility-level integration (same site)a | CONFAD, Brazil (1 health centre)34,36 | Family counselling centres, Honduras33 | ||||

| Level 2: comprehensive provider- and/or facility-level integration (same site)b | Profamilia, Dominican Republicc (6 family planning clinics)29,37 | OSCC - Malaysia (in 97 state and district hospitals)32 - Bangladesh (6 hospitals)38 - Namibia (several hospitals)16 - Thailand (1 hospital)39 | ||||

| Level 3: systems-level integration (multisite linkage)d | Inppares, Peruc (4 family planning clinics)37 | Prime II, Armenia (1 polyclinic)31 | ||||

| Plafam, Venezuelac (3 family planning clinics)40 | Women’s Friendly Hospital, Bangladesh (30 hospital facilities)30,41 | |||||

| Gender recovery centre, Kenya (1 private hospital)42 | ||||||

IPV, intimate partner violence; OSCC, One-Stop Crisis Centre; NGOs, nongovernmental organizations. a Integration of one or two IPV service components in vertical programmes. b Comprehensive range of IPV services delivered in one service setting. c These programmes could be classified under both levels 2 and 3, as they provide comprehensive services in one facility (with internal referrals), but also have referrals to external services. They aimed to be comprehensive in one facility, but started with multisite referrals. d Range of basic IPV services delivered at one setting, with external referrals to specialized services.

Provider- and/or facility-level integration at same site

Selective integration

Implemented at both primary and secondary level of health care, the first type of model is characterized by the integration of one or two service components for abused women (e.g. counselling or psychological therapy) in vertical programmes. For instance, in Honduras, regional family-counselling centres, based at regional mental-health clinics, provide individual and group counselling for abused women;33 there are no external referrals. Another example comes from a pilot project in Brazil, where a dedicated counselling programme – CONFAD – has been integrated at a medical-school health centre and provides basic and therapeutic counselling.34,36

Comprehensive integration

An alternative model is the provision of a comprehensive range of IPV services delivered in one setting. This is found most commonly in industrialized settings (particularly in the United States of America) and primarily at secondary or tertiary levels of care.43 Developing country examples include the One-Stop Crisis Centre (OSCC) model, initially developed in Malaysia (based on a Canadian model) for battered women and later extended to rape and sexual assault,28 and now implemented at a national level in Bangladesh, Malaysia, Namibia and Thailand.16,32 These operational centres offer a wide range of integrated services to address IPV, including health, legal, welfare and counselling services, in one location – usually the accident and emergency departments of urban public hospitals. Some of these centres have dedicated staff manning the centres at all times, others have core staff members and a list of contacts, such as psychologists and medical social workers, who can be called upon to provide specialized services on site when needed.

Systems-level integration (multisite linkage)

Though still offering a comprehensive package of services for abused women, the third type of model differs from the two previous ones because services are not all provided at the same site. A range of basic services, such as screening and medical care, is delivered at one facility, with external referrals to other facilities for specialized services. The examples reviewed are from both primary- and secondary-care levels, with reproductive-health services being the main entry point.

At the primary-care level, the three-site regional International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) project in Latin America44 integrated violence screening and related support services (counselling, legal advice) into existing sexual and reproductive health services.35,45 Affiliates’ clinics also strengthened their off-site referrals and established a partnership with local NGOs to refer abused women for psychological support and shelter.45 For instance, Plafam, in Venezuela, established external referrals to specialized psychological, legal and social services.40 Over the course of the project, the affiliates’ clinics (especially in the Dominican Republic) evolved into a more comprehensive model, trying to offer all the services at one facility, though challenges remained, including a scarcity of financial and human resources, and staff time constraints.

At secondary and tertiary levels, a range of medical IPV services has been integrated, mainly into maternity hospitals, with external referrals for other specialized services.25,30,31 For instance, in Bangladesh, the Women’s Friendly Hospital Initiative aimed to reduce maternal mortality and violence rates, and included treatment and referral for abused women among its services. On-site services included medical care, documentation of injuries, and external referral for social and legal support to other agencies or higher-level hospitals.30 In Armenia, Prime II project, has integrated IPV services in a polyclinic’s reproductive health services, and used a coordinated approach to strengthen external links to counselling, legal aid social support, hot-line services and shelter.31 A similar approach was used in a women’s hospital in Kenya, with referrals to NGOs for legal and economic support, shelter and police investigations.25

Challenges and opportunities

Several publications have discussed the challenges associated with integrating responses to gender-based violence into the health sector.16,35,46 The models described above illustrate how each may face common problems, but also that each model has both strengths and limitations. For instance, the OSCC model offers a broad range of health and legal services in one setting and is based in a non-stigmatized department. However, its location at a tertiary level may result in a more limited coverage than interventions implemented at a primary-care level. Being integrated within a reproductive-health clinic, and incorporating routine screening, the IPPF programme has the potential for broader outreach, but is dependent upon referring women externally to legal and other support services. Despite this, screening and detection rates increased in the three IPPF affiliates’ clinics after on-site integration and staff training,35 though some barriers, such as lack of time and of referrals to community services, remained.44

Human resources, training and management protocols

A major concern in the provision of services for violence is to ensure that women are not further victimized by the health sector, but are treated sensitively.28 Related to this, a common issue of concern among the various models is the challenge of ensuring that health personnel are appropriately trained to provide support services. Findings from the IPPF regional initiative in Latin America, for example, show that initially some providers discounted women’s stories, seemed uninterested, ignored the situation and focused on physical symptoms.45 However, over the course of the project, low knowledge and negative attitudes of providers towards screening for abuse seemed to decline, as staff, once trained, became more aware of the links between IPV and sexual and reproductive health,47,48 and felt more empowered and committed to raise the issue of violence with their clients.44

The models reviewed had different approaches to staff training. In the Dominican Republic, all staff of six family planning clinics offering screening, free-standing counselling and legal services, were trained, including receptionists and security staff,29 though the level of training was given strategically, as not all staff were expected to respond to IPV with equal competence and dedication. In Malaysia, only doctors and staff nurses from the accident and emergency and the gynaecology departments were trained, as they were the most involved in the provision of services.

Several models complemented training initiatives with the development of clear procedures and guidelines for providers that stated their required roles and competencies, and that established systems for supervision and ongoing monitoring. Studies of the Latin American and the Malaysian OSCC models suggest that the integration of policies, protocols and other tools and procedures for IPV response is important to help institutionalize IPV services as part of delivery care, and contributed to the improvement of their implementation.28,29,44

As an aspect of this, the sustainability of training in the long term is a common challenge for integration. For instance, lack of record-keeping, high staff turnover, and variations in local training programmes were constraints faced in the Malaysian programme.28,49

Financial, structural and health-system issues

Financial constraints appeared to be a challenge in all integrated models, but especially of the stand-alone, hospital-based OSCCs, where funds depend mainly on local hospital boards.49 Poor infrastructure, non-existent or poor documentation systems, and lack of private examination and counselling rooms were some of the challenges health services typically faced. The programmes reviewed illustrate good practices in these regards, especially around confidentiality and privacy, as private spaces were created for screening and treating abused women, and policies safeguarding confidentiality of medical records were reinforced.45 In Malaysia, colour coding or stamping on registration files were two systems developed to protect clients’ confidentiality.28,29,44 In the Dominican Republic, sound-proof clinic rooms were created, though the final evaluation showed that staff still entered consultation rooms while providers were with abused women.50

Partnerships with other agencies and organizations

It is important that health systems are able to facilitate women’s access to health and non-health services if needed. The stand-alone model of OSCCs aims to partially address this issue by providing a range of services within accident and emergency and other units of the hospital, as well as off-site referral for specialist non-health services, although referral to other settings may be limited by the options available. In Malaysia, despite most OSCCs providing temporary shelters to victims for the night, there was a lack of emergency shelters to which women could be referred.28 Generally, partnership with local women’s NGOs, whenever available, proves to be a crucial element for providing support services to abused women once discharged. In Venezuela, the multisite-linked model also experienced a paucity of referral sites and additionally had difficulties in following up cases that had been externally referred.40,44 On the other hand, in the Dominican Republic, Profamilia strengthened its off-site referrals, and established a partnership with local NGOs to refer abused women for psychological support and shelter.29,45

Conclusion

There is growing recognition of the public-health burden of IPV and the potential for the health sector to identify and support abused women. Drawing upon models of health-sector integration, this paper has reviewed current initiatives to integrate responses to IPV into the health sector in low- and middle-income settings.

The review is limited in some ways because very few of the identified programmes have been evaluated systematically. Available publications offered a descriptive analysis of some evaluated health-setting approaches, but little mention of the processes, or contextual factors, that influence an organization’s integration of IPV services. Therefore, it has been difficult to analyse some of the selected programmes, especially in low-income countries (Bangladesh and Kenya). Nevertheless, our review gives an overview of the range of responses being implemented, and illustrates the degree to which health systems in low- and middle-income settings are starting to engage with the issue of violence.

Our paper shows that many countries are actively seeking to respond to the issue. It appears that a few key models of integration are replicated in many settings, which can be characterized by their level and type of integration: (i) provider/facility-level integration providing selected or comprehensive services; and (ii) systems-level integration providing referral to services across multiple sites. The models provided services at primary, secondary and tertiary levels of care. Based on our findings, Fig. 1 presents a summary model of the entry points identified for integrating IPV services into existing health services (which see a range of presenting conditions) and the referrals necessary to ensure full systems-level integration.

Fig. 1.

Potential entry points for delivery of health care to abused women and systems of referral for effective integration

NGOs, nongovernmental organizations; STIs, sexually transmitted infections.

This paper highlights the multiple challenges faced at different levels of integration and in different country contexts. These range from individual service providers’ attitudes and lack of knowledge about violence to managerial and health systems’ challenges, such as insufficient staff training, lack of inclusion of violence-response training in national medical curricula, no clear policies on IPV, and lack of coordination among various actors and departments involved in planning integrated services. Furthermore, given the variety of locations where women may present and the range and potential severity of presenting health problems, there is an urgent need for coherent, effective referral within the health sector, and for strong local partnerships to facilitate effective referral to external, non-health services. The influence of more external structural and political issues (including laws on IPV and the availability of external sources of support for women experiencing violence) is also important.

Further research is needed to understand the successes and operational lessons to be learned for the scale-up in different settings. These need to be addressed if the quality and appropriateness of services provided is to improve. ■

Footnotes

Funding: World Health Organization, DFID and Sigrid Rausing Trust.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Prevention of violence: a public health priority [World Health Assembly]. Geneva: WHO; 1996.

- 2.García-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. WHO multi-country study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women Study Team. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368:1260–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.García-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Watts, CH, Ellsberg M, Heise L, WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women Study Team. WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses Geneva: WHO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359:1331–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, Kub J, Schollenberger J, O’Campo P, et al. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1157–63. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23:260–8. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kishor S, Johnson K. Profiling domestic violence: a multi-country study Calverton, MD: ORC Macro; 2004. p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riger S, Raja S, Camacho J. The radiating impact of intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2002;17:184–205. doi: 10.1177/0886260502017002005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Reed E, Raj A. Intimate partner violence victimization prior to and during pregnancy among women residing in 26 U.S. states: associations with maternal and neonatal health. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:140–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutton MA, Green BL, Kaltman SI, Roesch DM, Zeffiro TA, Krause ED. Intimate partner violence, PTSD, and adverse health outcomes. J Interpers Violence. 2006;21:955–68. doi: 10.1177/0886260506289178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hegarty KL, Bush R. Prevalence and associations of partner abuse in women attending general practice: a cross-sectional survey. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2002;26:437–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2002.tb00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruiz-Pérez I, Plazaola-Castaño J, Blanco-Prieto P, González-Barranco JM, Ayuso-Martin P, Montero-Piñar MI. Intimate partner violence. A survey conducted in the primary care setting. Gac Sanit. 2006;20:202–8. doi: 10.1157/13088851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dearwater SR, Coben JH, Campbell JC, Nah G, Glass N, McLoughlin E, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner abuse in women treated at community hospital emergency departments. JAMA. 1998;280:433–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.5.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst AA, Weiss SJ. Intimate partner violence from the emergency medicine perspective. Women Health. 2002;35:71–81. doi: 10.1300/J013v35n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kramer A, Lorenzon D, Mueller G. Prevalence of intimate partner violence and health implications for women using emergency departments and primary care clinics. Womens Health Issues. 2004;14:19–29. doi: 10.1016/S1049-3867(03)00115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watts C, Mayhew S. Reproductive health services and intimate partner violence: shaping a pragmatic response in sub-Saharan Africa. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2004;30:207–13. doi: 10.1363/3020704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson BA, Marshak HH, Hebbeler DL. Identifying intimate partner violence at entry to prenatal care: clustering routine clinical information. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2002;47:353–9. doi: 10.1016/S1526-9523(02)00273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell JC, Woods AB, Chouaf KL, Parker B. Reproductive health consequences of intimate partner violence. A nursing research review. Clin Nurs Res. 2000;9:217–37. doi: 10.1177/10547730022158555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson HD. Screening for domestic violence – bridging the evidence gaps. Lancet. 2004;364(Suppl 1):s22–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17627-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hegarty KL, Feder G, Ramsay J. Identification of intimate partner abuse in health care settings: should health professionals be screening? In: Roberts G, Feder G, Ramsay J, eds. Intimate partner abuse and health professionals: new approaches to domestic violence Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 79-92. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Askew I, Berer M. The contribution of sexual and reproductive health services to the fight against HIV/AIDS: a review. Reprod Health Matters. 2003;11:51–73. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(03)22101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayhew SH, Lush L, Cleland J, Walt G. Implementing the integration of component services for reproductive health. Stud Fam Plann. 2000;31:151–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2000.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berer M. Integration of sexual and reproductive health services: a health sector priority. Reprod Health Matters. 2003;11:6–15. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(03)02179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Pinho H, Murthy R, Moorman J, Weller S. Integration of health services. In: Sundari Ravindran TK, de Pinho H, eds. The right reforms? Health sector reforms and sexual and reproductive health Johannesburg: University of Witwatersrand; 2005: 215-63. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleischman Foreit KG, Hardee K, Agarwal K. When does it make sense to consider integrating STI and HIV services with family planning services? Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2002;28:105–7. doi: 10.2307/3088242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayhew S. Integrating MCH/FP and STD/HIV services: current debates and future directions. Health Policy Plan. 1996;11:339–53. doi: 10.1093/heapol/11.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell M, Mayhew S, Haivas I. Integration revisited [Background paper to the report: Public choices, private decisions: sexual and reproductive health and the millennium development goals]. United Nations Millennium Project; 2004. p. 74. Available from: http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/documents/Mitchell_Mayhew_and_Haivas-final.pdf [accessed on 5 June 2008].

- 28.Rastam A, editor. The rape report: an overview of rape in Malaysia All Women’s Action Society; 2002. p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogow D, editor. Living up to their name: Profamilia takes on gender-based violence Quality/Calidad/Qualite, Vol. 18. New York: Population Council; 2006. p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haque YA, Clarke JM. The Woman Friendly Hospital Initiative in Bangladesh setting: standards for the care of women subject to violence. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;78(Suppl 1):S45–9. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(02)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.IntraHealth International. Armenia: improving providers’ responses to violence against women PRIME II Voices N. 31; 2004. Available from: http://www.prime2.org/prime2/voice/home/454875.html?article=398 [accessed on 15 July 2008].

- 32.Hii MS. One-Stop Crisis Centre: a model of hospital-based services for domestic violence survivors in Malaysia. Innovations. Innovative approaches to population and development programme management 2001; 9: 53-72.

- 33.Violence against women: the health sector responds Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.d’Oliveira AF. Primary health care programs. Brazil’s response to gender based violence. In: The second Interagency Gender Working Group’s technical update on gender-based violence Washington DC: IGWG; 2005. Available from: http://www.igwg.org/eventstrain/tecupdate2.htm [accessed on 5 June 2008].

- 35.Guedes A. Addressing gender-based violence from the reproductive health HIV sector: a literature review and analysis Washington, DC: LTG Associates Population Technical Assistance Project POPTECH; 2004. p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schraiber LB, d’Oliveira AF. Violence against women and Brazilian health care policies: a proposal for integrated care in primary care services. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;78(Suppl. 1):S21–5. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(02)00040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guezmes A, Vargas L. Proyecto para combatir la violencia basada en genero en America Latina. Informe final de la comparacion entre Linea Basal y Linee de Salida en INPPARES, PLAFAM y PROFAMILIA New York: IPPF/RHO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Multi-sectoral programme on violence against women Dhaka: Ministry of Women and Children Affairs. Available from: http://www.mspvaw.org/ [accessed on 5 June 2008].

- 39.Grisurapong S. Establishing a one-stop crisis center for women suffering violence in Khonkaen hospital, Thailand. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;78(Suppl 1):S27–38. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(02)00041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guedes AC, Stevens L, Helzner JF, Medina S. Addressing gender violence in a reproductive and sexual health program in Venezuela. In: Haberland N, Measham D, eds. Responding to Cairo. case studies of changing practice in reproductive health and family planning New York: New York Population Council; 2002 pp. 257-73. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haque YA. The Woman Friendly Hospital Initiative in Bangladesh: a strategy for addressing violence against women. Development. 2001;44:79–81. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.development.1110267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fleischman J. Strengthening HIV/AIDS programs for women. In: Lessons for US policy from Zambia and Kenya: a report of the CSIS Task Force on HIV/AIDS Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies; 2005. p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- 43.National consensus guidelines on identifying and responding to victimization of domestic violence in health care settings Family Violence Prevention Fund; 2004. Available from: http://www.endabuse.org/programs/healthcare/files/Consensus.pdf [accessed on 5 June 2008].

- 44.Guezmes A, Vargas L. Proyecto para combatir la violencia basada en genero en America Latina. Informe final de la comparacion entre Linea Basal y Linea de Salida en INPPARES, PLAFAM y PROFAMILIA New York: International Planned Parenthood Federation/Western Hemisphere Region (IPPF/WHR); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bott S, Guedes A, Guezmes A. The health service response to sexual violence: lessons from IPPF/WHR member associations in Latin America. In: Jejeebhoy S, Shah I, Thapa S, eds. Non-consensual sex and young people: perspectives from the developing world New York: Zed Books; 2005. pp. 251-268. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garcia-Moreno C. Dilemmas and opportunities for an appropriate health-service response to violence against women. Lancet. 2002;359:1509–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08417-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bott S, Guedes A, Claramunt MC, Guezmes A. Improving the health sector response to gender-based violence: a resource manual for health care professionals in developing countries New York: International Planned Parenthood Federation/Western Hemisphere Region (IPPF/WHR); 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morrison A, Ellsberg M, Bott S. Addressing gender-based violence in the Latin American and Caribbean Region: a critical review of interventions Washington, DC: World Bank; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kelly L. Specialisation, integration and innovation: review of health service models for the provision of care to persons who have suffered from sexual violence. [Unpublished].

- 50.Bott S, Morrison A, Ellsberg M. Preventing and responding to gender-based violence in middle and low-income countries: a global review and analysis [World Bank Policy Research Working Paper]. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2005. p. 61. [Google Scholar]