Abstract

Objective

In the year 2000, the Philippines’ Department of Health adopted mass chemotherapy using praziquantel to eliminate schistosomiasis. Mass treatment was offered to an eligible population of 30 187 residents of 50 villages in Western Samar, the Philippines, in 2004 as part of an ongoing epidemiological study, Schistosomiasis Transmission and Ecology in the Philippines (STEP), aimed at measuring the effect of irrigation on infection with schistosomiasis. This paper describes the mass-treatment activities and factors associated with participation.

Methods

Advocacy, information dissemination and social mobilization activities were conducted before mass chemotherapy. Village leaders were primarily responsible for community mobilization. Mass treatment was offered in village meeting halls and schools. Participation proportions were estimated based on the 2002–2003 census. Community involvement was measured using a participation index. A Bayesian hierarchical logistic regression model was fitted to estimate the association between sociodemographic factors and residents coming to the treatment site.

Findings

A village-level average of 53.1% of residents (range: 21.1–85.3) came to the treatment site, leading to a mass-treatment coverage with an average of 48.3% (range: 15.8–80.7). At the individual level, participation proportions were higher among males, preschool and school-age children, non-STEP participants and among those who provided a stool sample. At the village-level, better community involvement was associated with increased participation whereas a larger census was associated with decreased participation.

Conclusion

The conduct of mass treatment in the 50 villages resulted in far lower participation than expected. This raises concern for the ongoing mass-treatment initiatives now taking place in developing countries.

Résumé

Objectif

En 2000, le ministère de la santé philippin a adopté la chimiothérapie de masse par le praziquantel pour éliminer la schistosomiase. Le traitement de masse a été proposé à une population justiciable de ce traitement, composée de 30 187 habitants de 50 villages du Samar occidental, aux Philippines, en 2004, dans le cadre d’une étude épidémiologique en cours, le projet STEP sur la transmission et l’écologie de la schistosomiase aux Philippines. Ce projet STEP vise à mesurer l’impact de l’irrigation sur l’infection par la schistosomiase. Le présent article décrit les opérations de traitement de masse et les facteurs liés à la participation à ce traitement.

Méthodes

Des opérations de sensibilisation, de diffusion de l’information et de mobilisation sociale ont été menées avant la chimiothérapie de masse. Ce sont principalement les chefs de village qui ont assuré la mobilisation communautaire. Le traitement a été proposé dans les salles de réunion et les écoles des villages. Les taux de participation ont été estimés sur la base du recensement de 2002-2003. L’implication de la communauté a été mesurée par un indice de participation. Un modèle de régression logistique hiérarchique bayésien a été appliqué pour estimer l’association entre des facteurs sociodémographiques et la venue des habitants sur le site de traitement.

Résultats

En moyenne dans les villages, 53,1% des habitants (plage de variation : 21,1 - 85,3) se sont rendus sur le site de traitement, ce qui donne un taux de couverture moyen de 48,3% (plage de variation : 15,8 - 80,7). Au niveau individuel, le taux de participation était plus élevé chez les hommes, les enfants d’âge préscolaire et scolaire, les personnes ne participant pas au projet STEP et ceux ayant fourni un échantillon de selles. A l’échelle des villages, une plus grande implication de la communauté était associée à une plus forte participation, tandis qu’un recensement plus large était associé à une faible participation.

Conclusion

Le traitement de masse réalisé dans 50 villages a donné lieu à une participation bien plus réduite que prévu. Cette observation est préoccupante pour les initiatives de traitement de masse en cours actuellement dans les pays en développement.

Resumen

Objetivo

En el año 2000, el Ministerio de Salud de Filipinas adoptó la antibioticoterapia masiva con prazicuantel como medio de eliminación de la esquistosomiasis. En 2004 se ofreció tratamiento masivo a una población idónea de 30 187 residentes en 50 aldeas de Samar occidental, Filipinas, como parte de un estudio epidemiológico en curso - Transmisión y Ecología de la Esquistosomiasis en Filipinas (STEP) - concebido para medir el efecto del riego en la infección por esquistosoma. En este artículo se describen las actividades de tratamiento masivo y los factores asociados a la participación.

Métodos

Antes de la antibioticoterapia masiva se llevaron a cabo actividades de promoción, difusión de información y movilización social. Los líderes de aldea fueron los principales responsables de la movilización comunitaria. Se ofreció tratamiento masivo en las salas de reunión y las escuelas de las aldeas. Los porcentajes de participación se estimaron a partir del censo de 2002-2003, y la implicación de la comunidad se midió empleando un índice de participación. Se aplicó un modelo jerárquico bayesiano de regresión logística para estimar la relación entre los factores sociodemográficos y la visita de los residentes al centro de tratamiento.

Resultados

A nivel de aldea, acudieron al centro de tratamiento una media del 53,1% de los residentes (intervalo: 21,1-85,3), lo que se tradujo en una cobertura de tratamiento masivo del 48,3% (intervalo: 15,8-80,7). A nivel individual, los porcentajes de participación fueron mayores entre los hombres, los niños en edad preescolar y escolar, los participantes ajenos a STEP y las personas que proporcionaron una muestra de heces. A nivel de aldea, una mayor implicación de la comunidad se asoció a una mayor participación; ésta disminuía en cambio cuanto mayor era el censo.

Conclusión

La práctica del tratamiento masivo en las 50 aldeas estudiadas se asoció a una participación muy inferior a la prevista. Esto suscita preocupación en relación con las iniciativas de tratamiento masivo que se están llevando a cabo en los países en desarrollo.

ملخص

الغرض

في عام 2000، تبنّت وزارة الصحة في الفلبين المعالجة الكيميائية الجموعية بالبرازيكونتيل للتخلُّص من داء البلەارسيات. وقد قُدِّمت المعالجة الجموعية للسكان المؤەلين لتلقِّي المعالجة وعددەم 187 30 يقيمون في 50 قرية في سامار الغربية في الفلبين، في إطار مشروع سراية داء البلەارسيات والبيئة في الفلبين عام 2004 كجزء من الدراسة الوبائية المتواصلة، بەدف قياس تأثير الري على العدوى بالبلەارسيات. وتصف ەذە الورقة أنشطة المعالجة الجموعية والعوامل التي ترافق المشاركة بەا.

الطريقة

أجريت أنشطة للدعوة ونشر المعلومات واستنەاض المجتمع قبل البدء بالمعالجة الكيميائية الجموعية. وقد كان القادة الريفيون ەم المسؤولين بشكل رئيسي عن استنەاض المجتمع. وقُدِّمت المعالجة الجموعية في قاعات الاجتماعات في القرى وفي المدارس. وقُدِّر عدد المساەمين وفقاً لإحصاء السكان لعامَيْ 2002-2003. وقيس الإسەام المجتمعي بمؤشر المشاركة، وعُدِّل نموذج التحَوُّف اللوجستي التراتبي المنسوب لبيزان لتقدير الترابط بين العوامل الاجتماعية والسكانية وبين المقيمين القادمين لمواقع المعالجة.

الموجودات

بلغ المعدل الوسطي لمستوى سكان القرية الذين قدموا إلى مواقع المعالجة (53.1%)، (وكان يتراوح بين 21.1 و85.3)، مما أدى للوصول إلى تغطية بالمعالجة الجموعية مقدارەا 48.3% (وكانت تـتراوح بين 15.8 و80.7). أما على الصعيد الفردي فقد كانت النسبة المئوية للمشاركة أعلى بين الذكور وقبل سن المدرسة وفي سن المدرسة وفي المشاركين من خارج المشروع وممن أعطوا عينات من البراز. وعلى صعيد القرى فقد ترافق الإسەام الأفضل للمجتمع مع زيادة المشاركة، في الوقت الذي كان فيە توسيع نطاق التعداد السكاني يترافق مع نقص المشاركة.

الاستنتاج

أدى إجراء المعالجة الجموعية في 50 قرية إلى مشاركة أقل بكثير مما كان متوقعاً، ويبعث ذلك القلق في النفوس حول المبادرات التي يتواصل تنفيذەا في المعالجة الجموعية في البلدان النامية.

Introduction

Schistosomiasis remains a major public health problem in the Philippines. Some 6.7 million people distributed in 1212 villages (barangays), predominantly in the islands of Leyte, Samar and areas of Luzon and Mindanao, are at risk of the disease.1 In 2000, the Philippines’ Department of Health adopted mass treatment as its schistosomiasis control strategy with the aim of disease elimination.2 Mass chemotherapy with praziquantel has proven cost-effective in high-prevalence areas such as China.3 The rationale and strategies for global schistosomiasis mass treatment were recently reviewed by the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative.4

In the Philippines, mass treatment is offered to all residents ≥ 5 years of age, in barangays with prevalence ≥ 15%, without the need for stool examination. Even though annual mass treatment is recommended, its frequency depends largely on the availability of praziquantel nationwide. When the drug stock is insufficient, priority is given to highly endemic areas.

This study is a secondary analysis of data collected as part of a research project entitled Schistosomiasis Transmission Ecology in the Philippines (STEP) which aimed to develop a dynamic model of the influence of anthropogenic changes due to rice farming on the transmission of Schistosoma japonicum parasitic worms. Results of the baseline part of this project have been published elsewhere.5,6 The design of STEP included the mass treatment of all residents of the 50 participating barangays to compare the 1-year risk of reinfection in irrigated and rain-fed barangays. Our intent was to treat all barangay residents including those who were not STEP participants. STEP participants were involved in intensive data collection activities. The conduct of the mass treatment was expected to be relatively uncomplicated, but coverage was much less than expected. Thus, here we describe in detail the mass-treatment activities and conduct secondary analyses to explore correlates of participation and coverage in 50 barangays in Western Samar province, the Philippines.

Methods

Study population

Prior to 2004, no schistosomiasis mass treatment had been offered in Western Samar. Health services in the Philippines are delivered through a hierarchy of health centres. The 50 study barangays did not have any main health centres but there were 12 barangay health stations (BHS) and 145 barangay health workers (BHWs). Neither stool examination for schistosomiasis nor its treatment are offered in BHS. Patients suspected of being infected are referred to the Schistosomiasis Control Unit (SCU) offices in the capital Catbalogan. Hence, before the mass treatment described here, only a very small proportion of the Western Samar population had ever been treated for schistosomiasis. Based on information from STEP, less than 1% of participants had been treated with praziquantel in the previous 12 months (data not shown).

All residents were offered praziquantel treatment. Selected residents from each barangay had participated in the STEP cohort study. The STEP project had a defined sample of 5995 individuals ≥ 5 years who consented to participate in the research.5,6 Detailed descriptions of research design, sample selection and baseline epidemiological findings appear elsewhere.5–7 The study design involved a follow-up assessment of human and animal infection 1 year after mass treatment of all willing residents, not just the STEP study participants.

Mass treatment advocacy and mobilization activities

Before the mass treatment, the STEP research team conducted six focus group discussion sessions among farmers, women and teachers of six barangays from different municipalities and with SCU team members. The focus groups were used to obtain community perceptions and beliefs about the cause, transmission, signs and symptoms, diagnosis, perceptions of severity and treatment of schistosomiasis. This information was used to develop messages to promote participation in the mass treatment. These messages were translated into the local dialect and used in culturally acceptable illustrated flipcharts and flyers.

The STEP research team, SCU, main health centres and BHS planned and coordinated the mass treatment implementation. In each barangay, 2 weeks before mass treatment, the STEP research team conducted an orientation workshop attended by community representatives including BHS midwives, barangay leaders, BHWs, school teachers and other residents suggested by the barangay leaders. The orientation included a description of schistosomiasis-associated symptoms, its impact on children’s school performance and the availability of effective treatment. Group discussion and sharing of experiences allowed the exchange of ideas and clarification of misconceptions about schistosomiasis presented using the flipcharts. Mass treatment as a schistosomiasis elimination tool was introduced with emphasis on the importance of very high community participation. The community representatives discussed and decided on the treatment sites, individuals to be mobilized to assist in the activity and their responsibilities during the mass treatment. The treatment sites were the BHS or barangay halls, and schools for school-age residents.

Posters about the activity were placed in strategic places and flyers announcing the date of the mass treatment and advantages of participation were distributed to each household. Moreover, the barangay heads were provided a list of the community residents who had been tested positive for S japonicum based on stool examination. It was emphasized that the people on that list should be prioritized and encouraged to participate in the mass treatment. In 46 barangays, activities included: (i) a barangay assembly, a public address system or ringing of the bell on the day of mass treatment (23 barangays); (ii) a house-to-house information saturation drive (seven barangays); or (iii) both approaches (16 barangays). Out-of-school youth and BHWs were mobilized for the house-to-house visits in 21 barangays. No additional dissemination was done in four barangays.

Community participation index

The 50 barangays were categorized according to the level of community involvement in the conduct of the mass chemotherapy. The community participation index included: the use of bandilyo (an individual announcing the activity using a megaphone), mass announcements and mass media to disseminate information (15 points), house-to-house visits for information dissemination (25 points), presence of the barangay mayor during the treatment activity (10 points), proportion of barangay officials (up to 20 points depending on the proportion) and of BHWs (up to 20 points depending on the proportion) completing their assigned tasks, and the participation of other residents (10 points). Based on these, barangays were classified as having low (< 25 points), fair (25–49 points), active (50–74 points) or high (≥ 75 points) involvement.

Census

The STEP research team conducted a census of the barangays in 2002–2003. All households identified on a map developed by the STEP project were visited and a structured questionnaire was used to obtain sociodemographic information.

Recording of mass-treatment participants

Based on census lists, residents appearing at the treatment registration area had their names checked as they presented themselves. They were also asked about the whereabouts of other family members and neighbours to assess residency and vital status and pregnancy status of non-participants. Information was recorded on consumption of both doses of praziquantel and adverse reactions (not reported here).

Praziquantel was administered in two equal split doses to give each individual a total of 60 mg/kg. The split doses were administered 4 hours apart with the first dose usually between 09:00 and 12:00. To facilitate the individual’s return for their second dose, their return time was written on their arm. In 12 barangays, the public address system or the community bell announced the commencement of the second-dose treatment. Towards the end of the day, BHWs and school children in seven barangays went to non-adherent residents’ houses to invite them to come back for their second dose.

Eligibility criteria

Enumerated individuals at least 5 years old were eligible for treatment. Exclusion criteria included hypertension measured on site, self-reported history of asthma, allergy, pregnancy, lactation, recent delivery, possible pregnancy, seizure disorder, past surgery or currently experiencing sickness. Participants who were drunk or had been treated in another barangay were excluded.

Directly observed treatment

The provision of praziquantel adhered to the Department of Health guidelines. Body weight was recorded and a physical health assessment was made by SCU physicians. Consumption of both doses of praziquantel was directly observed by BHWs.

Protection of human subjects

The research was approved by the institutional review board of Brown University and the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine. Written informed consent for individuals below 18 years old to receive praziquantel treatment was obtained and provided by parents. Since mass treatment was a health service usually delivered by the SCU in all endemic barangays, written informed consent of adults was not usually obtained.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were conducted in STATA,© version 8 (StataCorp. LP, College Station, TX, United States of America).8 Crude proportion prevalence odds ratios (POR) for the participation proportion were calculated with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) using the exact approach. The barangay-level median and interquartile range of the participation proportions were calculated for variables measured at the barangay level.

The participation proportion was estimated by dividing the number of enumerated individuals (≥ 5 years) who presented for treatment by the number of enumerated individuals (≥ 5 years). The coverage was estimated as the number of enumerated residents receiving both treatment doses divided by the number of enumerated individuals. Because people not eligible for the treatment were part of the denominator, we also estimated an adjusted coverage where the estimated number of eligible residents was calculated based on the age-gender distribution of eligible residents who did present themselves to the treatment site.

The effects of age, gender, having had a parasitological exam and its results, participating in the STEP project (individual-level) and method used to encourage participation, census and irrigation classification of the barangay (barangay-level) on presenting oneself for treatment were estimated using a Bayesian hierarchical logistic model. Variables that showed some association with the participation proportion in the descriptive analyses were included in the multivariate analysis. In addition, a model including all variables included in the community involvement index was fitted. The result of this model suggested that the index was more informative than any component of the index taken in isolation. Hence, we report the result from only one model here. The POR and their 95% Bayesian credible intervals (95% BCI) are reported. All Bayesian analyses were conducted using WinBUGS version 1.4 (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, England).9

Results

Population census

The 50 barangays had a total population of 35 199, of whom 30 991 were ≥ 5 years old. Of these, 128 were deceased and 676 had permanently moved away from the barangay at the time of the mass treatment and were excluded from the denominator, for an updated census of 30 187 people.

Mass-treatment participation

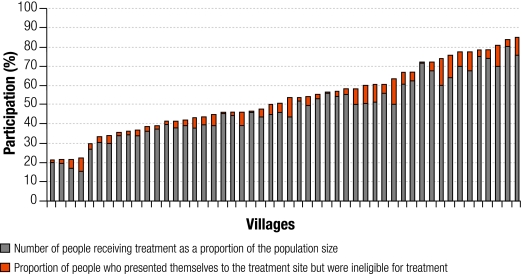

The estimated overall participation proportion was 48.6% (14 678/30 187) and the overall coverage was 44.4% (13 416/30 187). Using an adjusted eligible population of 28 268 people, the adjusted coverage was estimated to 47.5%. Fig. 1 shows the participation proportion and coverage at the barangay level. The barangay-level participation proportion ranged from 21.1% to 85.3% with a mean of 53.1%. The barangay-level coverage ranged from 15.8% to 80.7% with a mean of 48.3%.

Fig. 1.

Participation proportion and coverage of a schistosomiasis mass treatment programme offered in 50 barangays of Samar province, the Philippines, 2004

Barangay, village.

Eligibility to treatment

Among the 14 678 people presenting for treatment, 1262 (8.6%) were not eligible for treatment, with reasons known for ineligibility in 1151 (92.2%) of cases. Ineligibles were mostly females (75.7%). Pregnancy or lactation was the most common cause for exclusion (48.7%) followed by sickness (23.9%) and hypertension (17.8%). Other reasons for ineligibility occurred in ≤ 5% of cases.

Characteristics associated with participation

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of mass-chemotherapy participants and non-participants. The participation proportion was slightly higher in males than females. Preschool (5–10 years old) and school-age (10–16 years old) children had a higher participation proportion than adults, with the > 16–40 years old group participating the least. Among adults > 40 years, 38.0% of women and 40.6% of men participated. There were 5995 STEP participants (19.9% of all residents) with 4856 of them (81.0%) providing at least one stool sample. Another 1882 (7.8% of all residents) non-STEP participants provided one stool sample. Overall, the participation proportion was much higher among those with a positive stool sample (87.4%), followed by those with a negative stool sample (66.2%), compared to those who did not provide any stool samples (42.5%). This distribution was similar in STEP and non-STEP participants.

Table 1. Participation in mass treatment for schistosomiasis and proportion odds ratios associated with sociodemographic characteristics, among members of 50 barangays of Samar province, the Philippines, 2004.

| Variable | Number who participated | Percentage who participated | Proportion odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 7 822 | 49.2 | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) |

| Female | 6 856 | 48.0 | |

| Age in years | |||

| 5–10 | 4 079 | 62.8 | Reference |

| > 10–16 | 2 885 | 54.8 | 0.72 (0.68–0.77) |

| > 16–40 | 4 096 | 39.5 | 0.39 (0.36–0.41) |

| > 40 | 3 618 | 45.0 | 0.48 (0.45–0.52) |

| STEP participant | |||

| Yes | 3 644 | 60.8 | 1.85 (1.74–1.96) |

| No | 11 034 | 47.6 | Reference |

| Parasitological test conducted | |||

| Yes and positive for schistosomiasis | 1 049 | 87.4 | 9.40 (7.89–11.22) |

| Yes and negative for schistosomiasis | 3 666 | 66.2 | 2.65 (2.49–2.82) |

| No | 9 963 | 42.5 | Reference |

Barangay, village; CI, confidence interval; STEP, Schistosomiasis Transmission and Ecology in the Philippines.

Table 2 shows the median and interquartile range of the participation proportions according to the irrigation status, community involvement factors and the community participation index. The use of mass media to announce the mass treatment and the involvement of residents in the mass-treatment activities had some impact on the participation proportion. The community involvement index suggests that those barangays with low or fair involvement had a lower median participation proportion than those where it was active or high.

Table 2. Participation in a schistosomiasis mass treatment programme, according to barangay-level variables in 50 barangays, Samar province, the Philippines.

| Variable | Number | Median | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass media to announce treatmenta | |||

| Yes | 39 | 54.3 | 39.1–67.6 |

| No | 11 | 45.3 | 42.0–60.8 |

| House-to-house information saturation drive | |||

| Yes | 23 | 54.1 | 43.6–67.3 |

| No | 27 | 50.2 | 36.5–72.3 |

| Barangay captain present during the mass treatment | |||

| Yes | 22 | 52.6 | 42.0–67.3 |

| No | 28 | 50.4 | 40.4–50.4 |

| BHW involvement during mass treatment | |||

| None | 6 | 33.6 | 22.3–72.4 |

| Some | 14 | 57.9 | 42.0–63.8 |

| Full | 30 | 52.6 | 44.0–67.6 |

| Villagers helping in the mass treatment activities | |||

| Yes | 21 | 56.8 | 46.1–72.3 |

| No | 29 | 47.9 | 39.1–60.6 |

| Community involvement index | |||

| Low | 4 | 36.1 | 26.1–62.0 |

| Fair | 7 | 39.0 | 35.9–60.4 |

| Active | 26 | 54.2 | 45.3–67.6 |

| Full | 13 | 55.6 | 46.1–67.3 |

| Irrigation status of the barangay | |||

| Irrigated | 25 | 54.0 | 45.3–67.3 |

| Rain-fed | 25 | 47.9 | 35.9–63.8 |

Barangay, village; BHW, barangay health worker; IQR, interquartile range. a Mass media includes barangay assembly, public address system or ringing of the bell on the day of mass treatment itself.

Table 3 shows the results of the Bayesian hierarchical logistic model. There was a strong confounding effect between being a STEP participant and having had a parasitological exam. Whereas the crude POR suggested that being a STEP participant increased the participation proportion, the adjusted estimate suggested a decrease of participation among STEP subjects (POR: 0.71; 95% BCI: 0.65–0.78). Participation was increased among those with a positive parasitological exam (POR: 10.29; 95% BCI: 8.47–12.57) and a negative parasitological exam (POR: 2.87; 95% BCI: 2.60–3.17), as compared to no parasitological exam. No major interaction was found between STEP participation and provision of a stool sample. Being male slightly increased the probability of participation. Younger age groups tended to show higher participation proportion. No important interaction between age and gender was found.

Table 3. Resuls of the Bayesian hierarchical logistic model.

| Variables | Reference | POR | 95% BCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | |||

| > 10–16 | 5–10 | 0.73 | 0.67–0.79 |

| > 16–40 | 5–10 | 0.35 | 0.33–0.37 |

| > 40 | 5–10 | 0.45 | 0.42–0.48 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | Female | 1.05 | 1.00–1.10 |

| STEP participation | |||

| Yes | No | 0.71 | 0.65–0.78 |

| Parasitological exam for schistosomiasis | |||

| Positive | No exam | 10.29 | 8.47–12.57 |

| Negative | No exam | 2.87 | 2.60–3.17 |

| Barangay-level variables | |||

| Census (per increase of 100 inhabitants) | 0.94 | 0.90–1.00 | |

| Community involvement | |||

| Fair | Poor | 1.63 | 0.68–3.94 |

| Active | Poor | 2.16 | 0.98–4.87 |

| Full | Poor | 2.60 | 1.11–5.92 |

Barangay, village; BCI, Bayesian credible interval; POR, prevalence odds ratio; STEP, Schistosomiasis Transmission and Ecology in the Philippines.

At the barangay level, a higher community participation index was associated with increased participation. Also, for each increase of 100 people in the census (≥ 5 years old), the participation proportion was reduced by 6% (POR: 0.94, 95% BCI: 0.90–1.00).

Discussion

The goal of the Philippines’ Department of Health is a schistosomiasis-free nation using mass treatment. Our findings suggest that this goal may be difficult to achieve due to low levels of participation by residents of endemic barangays. Despite vigorous community preparation activities, coverage was < 50%, which will not be sufficient to eliminate schistosomiasis.10

Our results indicate that participation in mass treatment is determined by individual factors, such as age, gender and knowledge of infection status. The barangay-level community involvement index is also a good indicator of participation. However, even in barangays with high community involvement, the average participation was only 56%. Much more intensive and extensive community-based education, preparation and perhaps incentives may be required to increase participation and coverage. These need to be formulated after detailed qualitative and quantitative research in endemic barangays about schistosomiasis knowledge and attitudes, perceptions of the burden of disease and reasons for seeking or refusing treatment. Although such social science studies have been done elsewhere regarding other aspects of schistosomiasis, we found no published studies focused on the detailed correlates of successful mass treatment with praziquantel.11–13

The higher participation proportions of school-age children can be explained by treatment delivery in schools, a strategy which was not employed before. School-based programmes have been demonstrated to be the most cost-effective approach to control schistosomiasis.14,15 However, even the coverage among school-age children (aged < 16 years) was less than 60%, which is unlikely to lead to schistosomiasis elimination. A Nigerian study compared three modes of anti-schistosomal mass-treatment delivery to a population of 5–19-year-old residents in six villages: health facilities, schools or communities.16 Community delivery had the highest coverage with 72.2% (range: 69–73) compared to 44.3% (range: 39.5–62) for health facilities and 28.5% (range: 26.3–74.5) for schools, leading to the conclusion that school-age children, whether attending school or not, were covered better through community delivery.

Males were marginally more likely to participate in the mass treatment. We expected women in their reproductive years to have a much lower participation proportion than men in the same age group, but the difference was very small. The lack of a gender difference is overshadowed by the overall low participation in mass treatment among adults > 16–40 years.

Knowledge of positive infection status has a very strong impact on participation which is partly due to the active seeking of those infected. The higher participation among those with a negative parasitological exam suggests that individuals who have submitted a stool sample might have felt at risk of and vulnerable to infection. It is difficult to advocate that provision of stool samples will help improve participation in mass treatment. The cost-effectiveness of mass treatment derives partially from the absence of screening costs and the burden of providing stool samples. Among those who did not provide a stool sample, anecdotal comments collected in the village included the belief that they could not be infected since they did not frequent water bodies where the parasites are found. Such perceptions need to be corrected through intensive health education and promotion.

A surprising result was that participation in the STEP project was associated with a reduction of 41% in the mass-treatment participation proportion. A possible explanation is that STEP participants felt that they knew enough regarding the infection and did not need treatment. The STEP participants may also have been burdened by so much information, about schistosomiasis through their recruitment, answering of many questionnaires and provision of up to three faecal specimens, that they may have wanted to circumvent further data collection. When the additional mass-treatment information and mobilization campaigns occurred, the messages and social influences were not as salient. These are informed speculations and it is clear that we need much more detailed research on what motivates individuals, families and communities to participate in mass treatment for schistosomiasis.17

Our results show that more active community involvement was associated with an increase of 160% in the participation proportion. Despite using community participation for the information and mobilization activities, there was variation across communities in their abilities to mobilize barangay leaders and volunteers to actively campaign for mass treatment. Hence, one of the major challenges for implementing future mass-treatment campaigns would be to convince local authorities and villagers to contribute more time and effort to mass-treatment activities.

Decisions to use mass treatment as the primary method of schistosomiasis control and elimination must be discussed. Since exposure to infection starts with water contact, schistosomiasis prevention education should start in school, as is currently being done for malaria. The rationale and results of such school-based anti-schistosomal activities have been well described.14,18 The content of schistosomiasis education and control should be examined and scrutinized. It should include, among others, the need to address misconceptions about the vulnerability to the disease and the reactions to the drug. Including information on the economic impact of the disease and how it affects school performance of school children should also be explored.

In summary, we find that the conduct of anti-schistosomal mass treatment in 50 barangays in Samar, the Philippines, resulted in far lower participation than desired. Although we find it interesting and plausible that individual and community factors were related to higher participation, it is obvious that much more fundamental and applied behavioural and social science research must be conducted. The results of such research should improve the intensity, content and targeting of community- and individual-level information, education and incentives around mass treatment. ■

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the work of the project field staff, political leaders who allowed us to work in the 50 barangays, and the families and animal owners for their cooperation.

Footnotes

Funding: This project was funded by the NIH/NSF Ecology of Infectious Diseases programme, NIH Grant R01 TW01582.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Leonardo LR, Acosta L, Olveda RM, Aligui GD. Difficulties and strategies in the control of schistosomiasis in the Philippines. Acta Trop. 2002;82:295–9. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(02)00022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mass treatment strategy for the control/elimination of schistosomiasis: field operational guide Manila: Department of Health; 2000.

- 3.Yu D, Sarol JN, Jr, Hutton G, Tan D, Tanner M. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the impacts on infection and morbidity attributable to three chemotherapy schemes against Schistosoma japonicum in hyperendemic areas of the Dongting Lake region, China. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2002;33:441–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fenwick A, Webster J. Schistosomiasis: challenges for control, treatment and drug resistance. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19:577–82. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000247591.13671.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarafder MR, Balolong EJ, Carabin H, Bélisle P, Tallo VL, Joseph L, et al. A cross sectional study of Schistosoma japonicum prevalence in 50 villages of Samar Province, the Philippines. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGarvey ST, Carabin H, Balolong EJ, Bélisle P, Fernandez T, Joseph L, et al. Cross sectional associations between intensity of animal and human infection with Schistosoma japonicum in Western Samar, Philippines. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:446–52. doi: 10.2471/BLT.05.026427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez TJ, Jr, Tarafder MR, Balolong EJ, Willingham AL, Belisle P, Webster JP, et al. Prevalence of Schistosoma japonicum infection among animals in fifty villages of Samar Province, the Philippines. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:147–55. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2006.0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stata statistical software: release 8.0 College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiegelhalter D, Thomas A, Best N. WinBUGS, version 1.4. 2000. Available from:http://www.mrc-bsu.cam.ac.uk/bugs/welcome.shtml [accessed on 15 August 2008].

- 10.Williams GM, Sleigh AC, Li Y, Feng Z, Davis GM, Chen H, et al. Mathematical modelling of schistosomiasis japonica: comparison of control strategies in the People’s Republic of China. Acta Trop. 2002;2:253–62. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kloos H. Human behaviour, health education and schistosomiasis control: a review. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:1497–511. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00310-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchoa E, Barreto SM, Firmo JOA, Guerra HL, Pimenta FG, Lima e Costa MFF. The control of schistosomiasis in Brazil: an ethno–epidemiological study of the effectiveness of a community mobilization program for health education. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:1529–41. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danso-Appiah A, De Vlas SJ, Bosompem KM, Habbema JDF. Determinants of health-seeking behaviour for schistosomiasis related symptoms in the context of integrating schistosomiasis control within the regular health services in Ghana. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:784–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bundy DA, Wong MS, Lewis LL, Horton J. Control of geohelminths by delivery of targeted chemotherapy through schools. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84:115–20. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90399-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyatt H, Evans D, Lengeller C, Tanner M. Controlling schistosomiasis: the cost effectiveness of alternative delivery strategies. Health Policy Plan. 1994;9:385–95. doi: 10.1093/heapol/9.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mafe MA, Appelt B, Adewale B, Idowu ET, Akinwale OP, Adeneye AK, et al. Effectiveness of different approaches to mass delivery of praziquantel among school-aged children in rural communities in Nigeria. Acta Trop. 2005;93:181–90. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruun B, Aagaard-Hansen J. The sociocultural context of schistosomiasis control: current knowledge and future research needs [Working Paper 10]. In: Report of the Scientific Working Group meeting on Schistosomiasis Geneva: WHO; 2006. pp 76-84. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lansdown R, Ledward A, Hall A, Issae W, Yona E, Matulu J, et al. Schistosomiasis, helminth infection and health education in Tanzania: achieving behaviour change in primary schools. Health Educ Res. 2002;17:425–33. doi: 10.1093/her/17.4.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]