Abstract

One central goal of the enhanced Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative and the more recent Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) is to free up additional resources for public spending on poverty reduction. The health sector was expected to benefit from a considerable share of these funds. The volume of released resources is important enough in certain countries to make a difference for priority programmes that have been underfunded so far. However, the relevance of these initiatives in terms of boosting health expenditure depends essentially, at the global level, on the compliance of donors with their aid commitments and, at the domestic level, on the success of health officials in advocating for an adequate share of the additional fiscal space. Advocacy efforts are often limited by a state of asymmetric information whereby some ministries are not well aware of the economic consequences of debt relief on public finances and of the management systems in place to deal with savings from debt relief. A thorough comprehension of these issues seems essential for health advocates to increase their bargaining power and for a wider public to readjust expectations of what debt relief can realistically achieve and of what can be measured. This paper intends to narrow the information gap by classifying debt relief savings management systems observed in practice. We illustrate some of the major advantages and stated drawbacks and outline the policy implications for health officials operating in the countries concerned. There should be careful monitoring of fungibility (i.e. where untraceable funds risk substitution) and additionality (i.e. the extent to which new inputs add to existing inputs at national and international level).

Résumé

L’un des objectifs centraux de l’Initiative améliorée en faveur des pays pauvres très endettés (PPTE) et de l’Initiative multilatérale pour l’allègement de la dette (MDRI), plus récente, est de dégager des ressources supplémentaires pour les dépenses publiques en faveur de la réduction de la pauvreté. Dans ce cadre, il est normal que le secteur de la santé bénéficie d’une part importante de ces fonds. Le volume des ressources dégagées est suffisant dans certains pays pour modifier la situation de programmes prioritaires jusque là sous-financés. Néanmoins, ces initiatives ne serviront à stimuler les dépenses de santé que si, au niveau mondial, les donateurs tiennent leurs engagements en termes d’aide et que si, au plan national, les responsables de la santé sont suffisamment convaincants pour obtenir une part appropriée du budget public supplémentaire. Leurs efforts d’argumentation se heurtent souvent à une situation d’information à sens unique. Certains ministères sont peu au courant des conséquences économiques de l’allègement de la dette sur les finances publiques et des systèmes en place pour gérer les économies résultant de cet allègement. Une compréhension approfondie de cette problématique semble indispensable aux avocats de la santé pour accroître leur pouvoir de négociation et pour qu’un public plus large réajuste ses attentes quant à ce que l’allègement de la dette peut réellement permettre et à ce qui peut être mesuré. Le présent article s’efforce de combler ce manque d’information en proposant une classification des systèmes en place en matière de gestion des économies réalisées avec l’allègement de la dette. Il illustre certains de leurs avantages importants et inconvénients déclarés et expose leurs implications politiques pour les responsables de la santé dans les pays concernés. Il convient de suivre de près la fongibilité (à savoir le risque de substitution de fonds sans possibilités de suivi ) et l’additionnalité des fonds (à savoir dans quelle mesure les nouveaux apports s’ajoutent aux apports nationaux et internationaux déjà existants).

Resumen

Una meta fundamental de la Iniciativa mejorada para la reducción de la deuda de los países pobres muy endeudados (PPME) y de la más reciente Iniciativa Multilateral de Alivio de la Deuda (MDRI) consiste en liberar recursos adicionales para el gasto público dedicado a reducir la pobreza. Se esperaba que el sector de la salud se beneficiara de una parte considerable de esos fondos. El volumen de recursos liberados es en algunos países lo bastante importante para operar cambios reales en programas prioritarios que han estado subfinanciados hasta ahora. Sin embargo, el interés de estas iniciativas en cuanto a impulsar el gasto sanitario depende esencialmente, a nivel mundial, del cumplimiento por parte de los donantes de sus compromisos de ayuda y, a nivel nacional, de la eficacia con que los funcionarios de salud defiendan un reparto adecuado del espacio fiscal adicional. Los esfuerzos de promoción se ven limitados a menudo por una situación de asimetría de la información, pues algunos ministerios no son muy conscientes de las consecuencias económicas del alivio de la deuda en las finanzas públicas y de los sistemas de gestión implantados para manejar los ahorros derivados del alivio de la deuda. Una comprensión cabal de estas cuestiones parece esencial para dar más poder de negociación a los defensores de la salud y para que el público en general ajuste sus expectativas sobre lo que cabe esperar de forma realista del alivio de la deuda y sobre lo que es posible cuantificar. Este artículo aspira a colmar esa laguna de información clasificando los sistemas de gestión de los ahorros derivados del alivio de la deuda observados en la práctica. Ilustramos algunas de las principales ventajas e inconvenientes declarados y describimos las implicaciones normativas para los funcionarios de salud que operan en los países interesados. Es preciso seguir vigilando atentamente la fungibilidad (es decir, el riesgo de que unos fondos no rastreables se empleen en sustitución de otros) y la aditividad (es decir, la medida en que los nuevos insumos se añadan a los ya existentes a nivel nacional e internacional).

ملخص

إن أحد المرامي المحورية للمبادرة المعززة المتعلقة بالبلدان الفقيرة المثقلة بالديون، والمبادرة الأحدث المتعددة الأطراف لتخفيف عبء الدين ەو توفير موارد إضافية للإنفاق العام بغرض تقليص وطأة الفقر. ويتوقع من القطاع الصحي الاستفادة من قسط كبير من ەذە الأموال. فحجم الموارد المخصَّصة يمثل أەمية كبيرة في بلدان معينة، إذ أنە يُحدث فروقاً كبيرة في البرامج ذات الأولوية التي لاتزال تعاني من نقص التمويل، بيد أن ملاءمة ەذە المبادرات لتعزيز النفقات الصحية تعتمد بشكل أساسي على الصعيد العالمي على التزام المانحين بتعەداتەم بتقديم المساعدة، وعلى الصعيد الوطني على نجاح المسؤولين الصحيين في مناصرة الجەود المبذولة لتوفير نصيب كاف من الحيز المالي الإضافي. ومما يقيد في الغالب جەود المناصرة ، تباين المعلومات مما يحول دون إدراك بعض الوزارات للتبعات الاقتصادية الناجمة عن الإعفاء من الديون وأثرەا على المالية العامة، كما يحول دون فەم نظم الإدارة الموجودة للتعامل مع الوفورات الناجمة عن الإعفاء من الدين. فالفەم الدقيق لەذە القضايا يبدو ضرورياً للمدافعين عن الصحة بغية تعزيز قوتەم التفاوضية، وللجمەور العريض لإعادة صياغة توقعاتەم لما يمكن للإعفاء من الديون تحقيقە على أرض الواقع، ولما يمكن قياسە. وتەدف ەذە الورقة البحثية إلى تقليص الفجوة المعلوماتية من خلال تصنيف نظم إدارة الوفورات المحققة من الإعفاء من الدين استناداً إلى الملاحظة العملية. وقام الباحثون بتوضيح بعض مكامن القوة الرئيسية والإشارة إلى أوجە الضعف، وتوضيح الآثار السياسية للمسؤولين الصحيين العاملين في البلدان المعنية. ويجب إيجاد رصد دقيق للمنقولات (حيث تكون ەناك مخاطرة باستبدال الأموال التي لا يمكن اقتفاء أثرەا) وللمضافات (مدى ما تحققە المدخلات الجديدة من إضافات على المدخلات الحالية على المستوى الوطني والدولي).

Introduction

“The original focus of the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative was on removing the debt overhang and providing a permanent exit from rescheduling. Relief can also be used to free up resources for higher social spending aimed at poverty reduction to the extent that cash debt-service payments are reduced. These are now twin objectives.” The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), 1999.

Forty one of the poorest and most heavily indebted countries, of which 33 are located in sub-Saharan Africa, are currently eligible to benefit from debt reduction under the enhanced HIPC Initiative and from cancellation of multilateral debt under the more recent Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI). Many hopes and promises were attached to the launch of these initiatives. For the first time, the provision of debt relief was explicitly linked with the goal of poverty reduction: budgetary resources no longer needed for debt servicing were meant to be used for scaling up expenditure conducive to poverty reduction.1 Given the important role of health in the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals, and the fact that all eligible countries identify this sector as a priority in their Poverty Reduction Strategy papers (although to a variable extent), health was expected to benefit from significant additional resources.

More than one decade after the launch of the HIPC Initiative and two years after the implementation of MDRI, it has become evident that the situation is far more complicated. One dollar of debt relief does not necessarily translate into one additional dollar of expenditure on poverty (let alone specifically on health). The successful realization of the initiatives’ objective with regard to increased expenditure on poverty, and our capability to assess this question, depend on various internal and external factors. Internally, a very decisive one seems to be the ability of officials in ministries such as health and education to actively advocate for these resources. All too often, the ministry of health lacks crucial information about the overall amounts of debt relief available on an annual basis and about the procedures in place to manage them (Box 1).

Box 1. WHO working group on the financial impact of debt relief initiatives.

In 2006, a working group at WHO decided to take a closer look at current debt relief initiatives since various governments reported that they use HIPC funds for scaling up priority health interventions, notably their immunization programme.

Three main reasons fuelled and justified this enquiry:

(i) The necessity to provide additional (external and domestic) resources to the health sector of many developing countries in order to progress towards the Millennium Development Goals;

(ii) The potential magnitude of additional fiscal space provided as a result of the combined effect of different debt relief initiatives;

(iii) The lack of accurate information and analysis of the impact of debt relief on social sector spending in general and on health spending in particular, despite the wide publicity and importance attached to the launch of the HIPC initiative and the MDRI.1 The results of the scarce studies are mixed.2–5

The main objective of this work is to analyse and document the experience of countries benefiting from current debt relief initiatives and to assess the financial impact of these resources on the health sector and immunization programme. The findings should ultimately feed into clarifications and recommendations for WHO staff and national health officials on how debt relief may be used to scale up health financing.

Initial questions included: How much fiscal space is annually created in the budget of beneficiary governments as a result of debt relief? What is the share of resources allocated to the health sector? What are the mechanisms and procedures put in place to manage debt relief resources and how can health officials use them for their advocacy? And very importantly, are debt relief funds additional to ordinary resources for health at national and international level?

By September 2008, case studies for 9 countries – Burundi, Cameroon, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritania, Mozambique, Uganda, the United Republic of Tanzania and Zambia – had been conducted.

HIPC, Heavily Indebted Poor Countries; MDRI, Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative.

In this paper, we present a classification of debt relief savings management systems and illustrate the different types with findings from our country case studies. The proposed classification is not new. It was introduced by the IMF and The World Bank6 and has been used by other authors.7 However, a thorough comprehension of its meaning and implications is essential for health officials in beneficiary countries to increase their bargaining power and for a wider public not necessarily familiar with the economics of debt relief to readjust expectations of what debt relief can realistically achieve and of what can be measured. We also present the major external challenge, i.e. the question of additionality to other forms of foreign aid, which may prevent current debt relief initiatives from having the desired impact. Finally, we ask for improved transparency and information flow at the national and international levels and propose a broader research agenda to tackle this issue.

Understanding debt relief

Debt relief under the current international initiatives has been presented to the beneficiary countries and to the wider public as a major source of funding for poverty reduction. However, the provision of debt relief has rarely been accompanied by a proper explanation of the nature of these funds and the mechanisms in place to manage them. At the country level, this has often led to high expectations and sometimes to frustration within those ministries that were supposed to benefit most.

Debt relief resources differ from other financing sources in an important respect: They do not constitute fresh money arriving from external sources.8 Rather, their immediate effect is to allow treasuries to retain general budget resources that would have otherwise been spent on debt repayment. The fiscal space thereby created can either be used to increase expenditure items (related to poverty reduction, but not necessarily), to pay down domestic or foreign debt or to lower tax rates.9 Some countries may perceive the latter two options as being more cost-effective ways of reducing poverty over time, rather than scaling up social expenditure.

Importantly, expectations must take into account the relative magnitude of the funds in the country context and whether or not the debt had been serviced in full. For countries that had not been servicing their debt in full, the fiscal space resulting from its cancellation would be smaller than the announced volume of nominal debt relief. In principle, to qualify for the HIPC initiative, a country must clear existing arrears to its creditors. In some cases, however, additional bilateral and/or multilateral assistance has been provided to help the country finance such arrears. When compared to past and present levels of public health expenditure, the annual savings as a result of the combined effect of different initiatives (in terms of additional fiscal space) can be significant. Table 1 provides an overview of the total amounts of nominal HIPC and MDRI assistance committed to the 23 countries that graduated from the HIPC initiative (i.e. reached completion point). The last column indicates how the average annual HIPC assistance in the 10 years following the completion point compares to the level of public health spending. In the 23 countries, the released amounts are equivalent, on average, to 70% of public health spending in 2005 (in six countries this proportion is even higher than 100%). Certainly, we would not expect any country to channel the entire amount of HIPC debt service savings to the health sector. This comparison is solely meant to illustrate that when compared to the government outlays for health (rather than to other measures such as gross domestic product or the government’s total budget), the resources released annually by the HIPC Initiative can be significant. Note that the comparison does not include additional debt service savings, which may result under MDRI.

Table 1. Committed debt relief under the HIPC initiative and MDRI compared to public health spending (in million US$) in 23 countries, September 2008a.

| Countries at completion point for HIPC initiativeb | HIPC qualification date |

Nominal debt relief |

HIPC debt service relief compared to public health spending |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision point date | Completion point date | Under HIPCc | Under MDRI | Average annual HIPC debt reliefd A | Public health spending in 2005e B | A as a % of B | |

| Benin | Jul 2000 | Mar 2003 | 460 | 1 128 | 23 | 130 | 18 |

| Bolivia | Feb 2000 | Jun 2001 | 2 060 | 2 850 | 124 | 399 | 31 |

| Burkina Faso | Jul 2000 | Apr 2002 | 930 | 1 194 | 25 | 187 | 13 |

| Cameroon | Oct 2000 | Apr 2006 | 4 917 | 1 297 | 133 | 256 | 52 |

| Ethiopia | Nov 2001 | Apr 2004 | 3 275 | 3 319 | 144 | 309 | 47 |

| Gambia | Dec 2000 | Dec 2007 | 90 | 393 | 9.6 | 9 | 113 |

| Ghana | Feb 2002 | Jul 2004 | 3 500 | 3 921 | 236 | 277 | 85 |

| Guyana | Nov 2000 | Dec 2003 | 1 354 | 712 | 57 | 37 | 154 |

| Honduras | Jun 2000 | Apr 2005 | 1 000 | 2 739 | 75 | 369 | 20 |

| Madagascar | Dec 2000 | Oct 2004 | 1 900 | 2 397 | 62 | 106 | 58 |

| Malawi | Dec 2000 | Aug 2006 | 1 600 | 1 593 | 90 | 227 | 40 |

| Mali | Sep 2000 | Mar 2003 | 895 | 1 967 | 45 | 159 | 28 |

| Mauritania | Feb 2000 | Jun 2000 | 1 100 | 882 | 46 | 37 | 124 |

| Mozambique | Apr 2000 | Sep 2001 | 4 300 | 2 028 | 121 | 189 | 64 |

| Nicaragua | Dec 2000 | Jan 2004 | 4 500 | 1 928 | 192 | 209 | 92 |

| Niger | Dec 2000 | Apr 2004 | 1 190 | 1 063 | 66 | 50 | 132 |

| Rwanda | Dec 2000 | Apr 2005 | 1 316 | 523 | 46 | 97 | 47 |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | Dec 2000 | Mar 2007 | 263 | 64 | 6.5 | 6 | 102 |

| Senegal | Jun 2000 | Apr 2004 | 850 | 2 471 | 47 | 164 | 29 |

| Sierra Leone | Mar 2002 | Dec 2006 | 994 | 665 | 47 | 23 | 203 |

| Uganda | Feb 2000 | May 2000 | 1 950 | 3 522 | 81 | 183 | 44 |

| United Republic of Tanzania | Apr 2000 | Nov 2001 | 3 000 | 3 843 | 118 | 256 | 46 |

| Zambia | Dec 2000 | Apr 2005 | 3 900 | 2 783 | 151 | 211 | 72 |

| Total | 45 344 | 43 285 | |||||

HIPC, Heavily Indebted Poor Countries; MDRI, Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative. a Committed debt relief under the assumption of full participation of creditors. b In total, 41 countries are currently eligible for the HIPC Initiative. The table indicates the 23 countries at completion point. Ten countries receive interim debt relief as they were not at completion point at time of publication. Decision point dates are in parentheses: Afghanistan (July 2007), Burundi (August 2005), the Central African Republic (September 2007), Chad (May 2001), the Congo (March 2006), the Democratic Republic of Congo (July 2003), Guinea (December 2000), Guinea-Bissau (December 2000), Haiti (November 2006) and Liberia (March 2008). Eight countries are potentially eligible but have not yet qualified (i.e. pre-decision point countries): Comoros, Côte d’Ivoire, Eritrea, Kyrgyzstan, Nepal, Somalia, the Sudan and Togo. c Includes assistance under the original and the enhanced framework and topping up at completion point. d Refers to the average annual nominal HIPC relief in the first 10 years following the completion point as indicated in the countries’ completion point document. e Public health spending refers to general government expenditure on health (in 2005), i.e. the sum of outlays by government entities to purchase health-care services and goods, notably by ministries of health and social security agencies. Besides domestic funds it also includes external resources (mainly as grants passing through the government or loans channelled through the national budget).10

Debt relief management systems

With the inception of debt relief, recipient countries face a difficult policy choice. Should the savings from debt relief be managed in a different way from ordinary public resources, or not? On the one hand, donors and citizens ask for some reassurance that savings from debt relief are effectively used to increase spending on poverty reduction. To accommodate this demand, and in the light of rather weak public expenditure management systems, some countries have introduced specific mechanisms to deal with the proceeds from debt relief in parallel to their existing systems. On the other hand, a country’s objective in the long run should be to improve the overall public expenditure management in view, to report on all public spending for poverty reduction. Creating a parallel system to track and report specifically on the use of debt relief savings may undermine such efforts. Our research shows that qualifying countries have adopted various approaches to deal with debt relief savings. Here we present three typical settings that are found in practice.6,7

Type 1: Institutional fund mechanism

This system deliberately introduces a framework that allows clear distinction between the allocation and use of debt service savings and ordinary public resources. The extent of specificity can best be illustrated by the example of Cameroon where the following elements have been created:11

A special treasury account at the Bank of Central African States to deposit the savings from HIPC relief;

A special codification for HIPC funds in the budget, which makes them easily distinguishable from other budget lines;

A monitoring committee consisting of representatives from the ministries, development partners and civil society;

Regular technical and financial audits for projects financed through HIPC funds.

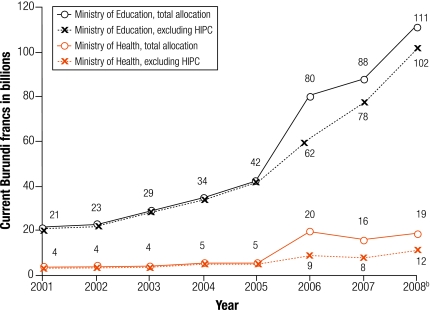

As a consequence of this specific framework, HIPC resources are to an important extent off-budget. A supposed advantage is to provide a clear picture of what has been financed with debt relief resources. In addition, for health officials in concerned countries, it is quite easy to know the overall amounts of annually available debt relief resources and the mechanisms involved in accessing these funds. Advocacy efforts can be targeted at these resources by submitting specifically designed projects for approval. Box 2 and Fig. 1 illustrate the example of Burundi where health advocates managed to receive more than one-third of the available debt relief savings from 2006 to 2008.

Box 2. Burundi: a case study of an institutional fund mechanism.

Burundi reached the decision point under the enhanced HIPC initiative in August 2005 and has been granted interim debt relief of about US$ 82 million in 2005–2007. On average, the annual amount of debt service savings represented 8% of the government’s budget. The resources generated by debt relief are set aside in a separate bank account and managed outside the general budget. It is therefore possible to follow the specific allocation and use of HIPC resources.

The health sector has been granted a very significant share of HIPC funds, receiving on average 35% of annual resources generated from 2006 to 2008. Health and education together accounted for three-quarters of total HIPC allocations.

Fig. 1 illustrates that the HIPC resources in the years under consideration do not seem to have crowded out ordinary government allocations to the ministries of health and education (as indicated by the dotted line). Importantly, while HIPC resources for education were slightly more important in absolute terms, they made a much bigger relative impact on health expenditures. As a result of HIPC resources, Burundi’s health sector budget more than doubled.

HIPC, Heavily Indebted Poor Countries.

Fig. 1.

Burundi: trend in government’s ordinary budget allocations and HIPC funds to the ministries of health and education, 2001–2008a

HIPC, Heavily Indebted Poor Countries.

a Figures supplied by the Ministry of Finance, Burundi.

b Data for 2008 are projections.

Despite these apparent advantages, the institutional fund mechanism must be evaluated critically for two reasons. First, setting up separate institutional arrangements to manage the proceeds from debt relief may divert scarce human resources, capacities and attention away from the ordinary public expenditure management system. Second, the tracking of HIPC expenditures alone does not provide any guarantee for additional resources to the beneficiary sectors. Due to fungibility of funds (i.e. where untraceable funds risk substitution), a government might be tempted to reduce ordinary allocations to programmes that are already benefiting from debt relief resources. In such a context, it is therefore crucial to monitor and ensure that debt relief resources do not crowd out ordinary government spending but are provided in addition to it. However, the concept of additionality (i.e. the extent to which new inputs add to existing inputs at national and international level) is somewhat ambiguous and not undisputed. The inherent difficulty of this notion is that it requires a judgement of what would have happened to ordinary government spending in the absence of debt relief. It is basically for these reasons that the IMF and the International Development Association (IDA) discourage the implementation of institutional fund mechanisms for the management of debt relief resources.6,12

Type 2: Virtual fund mechanism

An interesting intermediary approach to the management of debt relief savings is the set up of a virtual fund mechanism. Under this system, the country’s existing budget classification is adapted to tag (e.g. by using a special code) the savings from debt relief. The amounts released by debt relief, and in some cases the related expenditures, can be identified and tracked easily. Relying on the normal government procedures and standards for allocation, reporting and auditing, the virtual fund mechanism has the advantage of being fully on-budget by providing at the same time reassurance to donors and citizens regarding the use of debt relief resources. In 1998, Uganda was the first country to set up a virtual fund to ‘ring-fence’ resources for the implementation of poverty-reduction programmes.13 In the early years, HIPC debt relief resources were the major driving force behind increases in this funding. The IMF and the IDA welcome virtual funds as a temporary (bridging) mechanism to facilitate immediate tracking of poverty reducing expenditure, as long as they are conducive to the long-term goal of effective and comprehensive public expenditure management systems.6,12

Type 3: Comprehensive expenditure tracking

At the other extreme are countries that abstained completely from any specific institutional arrangements or tracking for debt relief savings: Examples from our case studies are Malawi, Mozambique and the United Republic of Tanzania. The same allocation, reporting and accountability standards are used for debt relief funds and traditional budget resources. Depending on the accounting standards, debt relief resources may still be identified on the revenue side of the budget, but there is complete fungibility when it comes to expenditures. The major consequence in the context of our initial question is that potential benefits from debt relief initiatives for the health sector cannot be measured directly. The only way to assess whether the health sector may have indirectly benefited in this instance is to take a closer look at the overall level and trends of public health spending.

Comprehensive expenditure tracking systems, which allow reporting on all poverty-reducing public expenditure (not just that financed by debt relief), are clearly the favoured approach by the IMF and The World Bank.6,12 While this is certainly the desired option in the long run, it requires strong public expenditure management systems that provide enough assurance to donors and citizens that debt relief indeed helps to boost poverty related spending. Many of the countries analysed still display weaknesses in several areas of their public expenditure management.14

Other drawbacks were mentioned by officials in the ministries of health during our country visits: Most importantly, compared to a type 1 or type 2 setting, there seems to be less information and transparency concerning the actual amounts of annual budgetary savings resulting from debt relief initiatives. We witnessed a state of asymmetric information, whereby the ministry of finance seems to be well informed about the potential fiscal space created by debt relief, while other ministries often lack this data. As a consequence, the ministry of health’s bargaining power for resources (which are also intended to benefit the health sector) may be reduced.

The policy implication for health officials operating in a type 3 setting is that no direct advocacy for debt relief funds is possible. Efforts to scale up public health spending must focus on negotiations for the overall budget envelope. Experience from the case studies show that the ministry of health’s bargaining power could be enhanced by:

Satisfactory past and present performance of the ministry of health in terms of planning, budgeting, management of funds and outcome indicators;

Good reputation of the ministry of health/health sector regarding governance (i.e. no scandals in the ministry, no perceived misuse of funds);

A high absorption capacity, as evidenced by high implementation rates in the past;

The credibility and comprehensiveness of the sectoral multiyear planning instrument;

A good understanding of the magnitude and composition of the funding available to the government for public expenditure (this includes being aware of how much debt relief has been received on an annual basis).

Additionality as a major external challenge

Donors have pledged that the amounts provided as debt relief would not compromise the volumes of other forms of official development assistance. This commitment is crucial and any breach would reduce the net benefit in terms of increased fiscal space in beneficiary countries. It is therefore essential to monitor net resource flows to assess whether donors comply with their initial promises.15–17 A vital question with regard to MDRI is whether donors will provide sufficient additional resources to multilateral lending institutions (such as the IDA and the African Development Bank) to compensate them for the incurred losses.18,19 The implementation mechanisms applied by the IDA and the African Development Bank may lead to outcomes where individual countries are worse off after MDRI.20 This is because MDRI alters the future lending policies of these institutions. The IDA, for instance, deducts, in a first step, an eligible country’s forgone debt service in any given year from its performance-based annual IDA allocation. In a second step, compensatory donor resources will be reallocated across all IDA-only countries (except ‘gap’ countries) according to their performance. However, here again, measuring the real additionality of debt relief funds is difficult since it requires a counterfactual assumption regarding what would have been the volumes of traditional bilateral and multilateral development assistance in the absence of any debt relief.

Conclusion

Current debt relief initiatives can be an option for scaling up health financing. The volumes of released resources are important enough in certain countries to make a difference for priority programmes that have been underfunded so far. The relevance of these initiatives in terms of boosting health expenditure depends essentially, at the global level, on the compliance of donors with their foreign aid commitments, and at domestic level, on the success of health officials in advocating for an adequate share of the additional fiscal space. The occurrence of internal or external shocks to the country’s economy may offset completely the potential benefits.

Knowledge and information about annual debt service savings and management systems, currently often monopolized by ministries of finance and/or the international financial institutions, should be made available to other ministries to ensure transparency and accountability. In addition, international financial institutions should enhance transparency and improve communication with the concerned countries regarding the procedures used to deliver MDRI assistance, and in particular, its actual degree of additionality.

In light of the trend towards comprehensive expenditure tracking systems, the strengthening of the ministry of health’s capacity in strategic planning, budget management and good governance becomes crucial. Furthermore, it seems desirable to support health officials beyond their technical role to encourage greater and more efficient involvement in the wider political arena (i.e. to make health priorities more prominent in their Poverty Reduction Strategy papers). More country-specific research would be desirable to assess the overall impact of debt relief on the availability of additional resources for priority interventions and on its effectiveness (compared to other aid instruments) in terms of improving (health) outcomes. Assessing this question by distinguishing the three standard types of debt relief management systems would be revealing. Finally, cross-country impact analysis of different policy choices regarding the use of debt relief savings (reducing taxes versus reducing domestic or external borrowing versus increasing social spending) would certainly shed new light on the discussion surrounding the optimal choices for achieving health promotion and poverty reduction. ■

Footnotes

Funding: The Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals at WHO receives support from the GAVI Alliance.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative and Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) [Status of implementation]. Washington, DC: IDA/IMF; 2008. Available from: http://www.imf.org/external/pp/longres.aspx?id=4278 [accessed on 23 September 2008].

- 2.Lora E, Olivera M. Public debt and social expenditure: friends or foes? [working paper no. 563]. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank; 2006. Available from: http://ssrn.com/abstract=905964 [accessed on 18 September 2008].

- 3.Hepp R. Health expenditures under the HIPC initiative [PhD dissertation]. Santa Cruz: University of California; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dessy SE, Vencatachellum D. Debt relief and social service expenditure: the African experience, 1989-2003. Afr Dev Rev. 2007;19:200–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8268.2007.00154.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chauvin ND, Kraay A. What has 100 billion dollars worth of debt relief done for low income countries? Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tracking of poverty-reducing public spending in heavily indebted poor countries (HIPCs) Washington, DC: IMF & IDA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Groot A, Jennes G, Cassimon D. The management of HIPC funds in recipient countries: a comparative study of five African countries [Synthesis report, study commissioned by the EC DG Development]. Rotterdam: ECORYS; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arslanalp S, Henry PB. Helping the poor to help themselves: debt relief or aid? [working paper 10234]. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassimon D, Van Campenhout B. Comparative fiscal response effects of debt relief: an application to African HIPCs [working paper 63]. Paris: Agence Française de Développement; 2008. Available from: http://www.afd.fr/jahia/Jahia/lang/en/home/documentsdetravail/pid/4772 [accessed on 18 September 2008].

- 10.National health accounts, country information. Geneva: WHO; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/nha/country/en/ [accessed on 23 September 2008].

- 11.Cameroon: enhanced Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative - completion point document and Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) [country report no. 06/190]. Washington, DC: IMF; 2006. Available from: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2006/cr06190.pdf [accessed on 18 September 2008].

- 12.Actions to strengthen the tracking of poverty-reducing public spending in Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPCs) Washington, DC: IMF & IDA; 2002. Available from: http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/pe/newhipc.pdf [accessed on 18 September 2008].

- 13.Pro poor spending reform – Uganda’s virtual poverty fund [PREM Notes 108]. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2006. Available from: http://www1.worldbank.org/prem/PREMNotes/premnote108.pdf [accessed on 18 September 2008].

- 14.De Renzio P, Dorotinsky B. Tracking progress in the quality of PFM Systems in HIPCs: an update on past assessments using PEFA data [report commissioned by PEFA program]; 2007. Available from: http://www.pefa.org/report_studies_file/HIPC-PEFA%20Tracking%20Progress%20Paper%20FINAL_1207944117.pdf [accessed on 18 September 2008].

- 15.Development co-operation report 2007, vol. 9, no.1. DAC/OECD;2008. Available from: www.oecd.org/dac/dcr [accessed on 18 September 2008].

- 16.Statistical annex to the development co-operation report 2007 DAC/OECD;2008. Available from: http://titania.sourceoecd.org/pdf/dac/432008011e-06-statisticalannex.pdf [accessed on 18 September 2008].

- 17.Debt relief for the poorest: an evaluation update of the HIPC Initiative Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2006. Available from http://www.worldbank.org/ieg/hipc/report.html [accessed on 18 September 2008].

- 18.Moss T. Will debt relief make a difference? Impact and expectations of the multilateral debt relief initiative [working paper no. 88]. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development; 2006. Available from: http://www.cgdev.org/content/publications/detail/7912/ [accessed on 18 September 2008].

- 19.Hurley G. Multilateral debt: one step forward, how many back? Brussels: EURODAD; 2007. Available from: http://www.eurodad.org/debt/report.aspx?id=112&item=01234 [accessed on 18 September 2008].

- 20.IDA’s Implementation of the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative. Washington, DC: IDA; 2006. Available from: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTDEBTDEPT/Resources/35765.pdf [accessed on 23 September 2008].