Abstract

Objective

To assess the effects of a comprehensive, integrated community-based lifestyle intervention on diet, physical activity and smoking in two Iranian communities.

Methods

Within the framework of the Isfahan Healthy Heart Program, a community trial was conducted in two intervention counties (Isfahan and Najaf-Abad) and a control area (Arak). Lifestyle interventions targeted the urban and rural populations in the intervention counties but were not implemented in Arak. In each community, a random sample of adults was selected yearly by multi-stage cluster sampling. Food consumption, physical exercise and smoking behaviours were quantified and scored as 1 (low-risk) or 0 (other) at baseline (year 2000) and annually for 4 years in the intervention areas and for 3 years in the control area. The scores for all behaviours were then added to derive an overall lifestyle score.

Findings

After 4 years, changes from baseline in mean dietary score differed significantly between the intervention and control areas (+2.1 points versus –1.2 points, respectively; P < 0.01), as did the change in the percentage of individuals following a healthy diet (+14.9% versus –2.0%, respectively; P < 0.001). Daily smoking had decreased by 0.9% in the intervention areas and by 2.6% in the control area at the end of the third year, but the difference was not significant. Analysis by gender revealed a significant decreasing trend in smoking among men (P < 0.05) but not among women. Energy expenditure for total daily physical activities showed a decreasing trend in all areas, but the mean drop from baseline was significantly smaller in the intervention areas than in the control area (–68 metabolic equivalent task (MET) minutes per week versus –114 MET minutes per week, respectively; P < 0.05). Leisure time devoted to physical activities showed an increasing trend in all areas. A significantly different change from baseline was found between the intervention areas and the control area in mean lifestyle score, even after controlling for age, sex and baseline values.

Conclusion

The results suggest that community-based lifestyle intervention programmes can be effective in a developing country setting.

Résumé

Objectif

Evaluer les effets d’une intervention en communauté intégrée et complète, visant à modifier le mode de vie, sur l’alimentation, l’activité physique et le tabagisme dans deux communautés iraniennes.

Méthodes

Dans le cadre du Programme pour la santé cardiaque d’Isfahan, un essai en communauté a été mené dan deux régions administratives d’intervention (Isfahan et Najaf-Abad) et dans une zone témoin (Arak). Les interventions pour modifier le mode de vie visaient des populations urbaines et rurales des régions administratives d’intervention et n’ont pas été mises en œuvre dans la région d’Arak. Dans chaque communauté, on a sélectionné un échantillon aléatoire d’adultes en procédant chaque année à un sondage en grappes à plusieurs degrés. La consommation d’aliments, l’exercice physique et les habitudes tabagiques ont été quantifiés et affectés d’un score de 1 (risque faible) ou de 0 (autre) pour l’année de référence (2000) et chaque année pendant les 4 ans suivants dans les zones d’intervention et pendant les 3 ans suivants dans la zone témoin. On a ensuite ajouté les scores pour l’ensemble des comportements afin de déterminer un score global de mode de vie.

Résultats

Au bout de 4 ans, les évolutions par rapport au score de référence moyen différaient significativement entre zones d’intervention et zone témoin pour le régime alimentaire (+2,1 points contre -1,2 point, respectivement ; p < 0,01), comme pour le pourcentage d’individus suivant un régime alimentaire sain (+14,9% contre -2,0%, respectivement ; p < 0,001). A la fin de la troisième année, le tabagisme quotidien avait baissé de 0,9% dans les zones bénéficiant de l’intervention et de 2,6% dans la zone témoin, mais cet écart n’était pas significatif. L’analyse selon le sexe a révélé une tendance significative à la baisse du tabagisme chez les hommes (p < 0,05), mais pas chez les femmes. La dépense énergétique correspondant à l’ensemble des activités physiques quotidiennes manifestait une tendance à la baisse dans toutes les zones, mais la diminution moyenne par rapport à la référence était significativement plus faible dans les zones bénéficiant de l’intervention (-68 MET (équivalents métaboliques)-minutes/semaine contre -114 MET-minutes/semaine, respectivement ; p < 0,05) que dans la zone témoin. Le temps de loisir consacré à des activités physiques présentait une tendance à l’augmentation dans toutes les zones. On a relevé une variation statistiquement significative du score de mode de vie entre les zones bénéficiant de l’intervention et la zone témoin, même après élimination de l’influence de l’âge, du sexe et des valeurs de référence.

Conclusion

Les résultats laissent à penser que les programmes d’intervention en communauté pour modifier le mode de vie peuvent être efficaces dans un pays en développement.

Resumen

Objetivo

Evaluar los efectos de una intervención comunitaria integral e integrada sobre el modo de vida centrada en el régimen alimentario, la actividad física y el tabaquismo en dos comunidades iraníes.

Métodos

En el marco del Healthy Heart Program (Programa Corazón Sano) de Isfahan, se llevó a cabo un ensayo comunitario en dos distritos de intervención (Isfahan y Najaf-Abad) y una zona de control (Arak). Las intervenciones sobre el modo de vida se focalizaron en las poblaciones urbanas y rurales en los condados de intervención pero no se aplicaron en Arak. En cada comunidad, se procedió a seleccionar cada año una muestra aleatoria de adultos mediante muestreo multietápico por conglomerados. Los comportamientos relacionados con la dieta, el ejercicio físico y el consumo de tabaco se cuantificaron y calificaron como 1 (de bajo riesgo) o bien 0 (otro caso) al inicio del estudio (año 2000), y después de forma anual, durante 4 años en las áreas de intervención, y durante 3 años en la zona de control. Por último, se sumaron las puntuaciones correspondientes a cada comportamiento para obtener una puntuación general del modo de vida.

Resultados

Al cabo de 4 años, la variación de la puntuación media de la dieta difirió de forma significativa entre las zonas de intervención y las de control (+2,1 puntos frente a -1,2 puntos, respectivamente; p < 0,01), al igual que la variación del porcentaje de individuos que seguían una dieta saludable (+14,9% frente a -2,0%, respectivamente; p < 0,001). La costumbre de fumar diariamente había disminuido en un 0,9% en las zonas de intervención, y en un 2,6% en la zona de control al final del tercer año, pero la diferencia no era significativa. El análisis por género mostró una tendencia significativa a la disminución del tabaquismo entre los hombres (p < 0,05), pero no así entre las mujeres. El gasto energético asociado a la actividad física diaria total mostró una tendencia a la baja en todas las zonas, pero la caída media respecto a los valores basales fue significativamente menor en las zonas de intervención que en la zona de control (-68 minutos de tarea metabólica equivalente (MET) por semana, frente a -114 minutos de MET semanales, respectivamente; p < 0,05). El tiempo de ocio dedicado a actividades físicas mostró una tendencia al aumento en todas las zonas. Se observó una diferencia significativa en la variación respecto a los valores iniciales entre las zonas de intervención y la zona de control en lo relativo a la puntuación media del modo de vida, incluso después de controlar los datos en función de la edad, el sexo y los valores basales.

Conclusión

Los resultados parecen indicar que los programas comunitarios de intervenciones sobre el modo de vida pueden ser eficaces en el entorno de los países en desarrollo.

ملخص

الەدف

تقيـيم تأثيرات تدخل شمولي متكامل لأنماط الحياة المجتمعية الخاصة بالنظام الغذائي والنشاط البدني والتدخين في اثنين من المجتمعات الإيرانية.

الطريقة

أجريت تجربة مجتمعية في مقاطعتَيْن (محل المداخلة ەما إصفەان ونجف أباد) ومنطقة شاەدة (أراك) ضمن إطار برنامج صحة القلب في إصفەان، وقد نُفِّذَت التدخلات على أنماط حياة السكان من الريف والمدن في المقاطعتَيْن المذكورتَيْن ولم تستەدف السكان في المقاطعة الشاەدة أراك. وفي كل واحد من المجتمعات المدروسة، تم أخذ عيّنة عشوائية من البالغين كل عام باتباع الاعتيان العنقودي المتعدد المراحل. وأجريت تقديرات كمية لسلوكيات استەلاك الطعام، والتمرين البدني، والتدخين. وأعطيت أحرازاً (درجات) ەي 1 للاختطار المنخفض و0 لغير ذلك، وتم ذلك في خط الأساس (عام 2000)، ثم كل عام لمدة 4 سنوات في مقاطعتي التدخل وكل 3 سنوات في المنطقة الشاەدة، ثم أضيفت الأحراز (الدرجات) الخاصة بجميع السلوكيات لاستنباط حرز إجمالي لنمط الحياة.

الموجودات

بعد مرور 4 سنوات تبيَّن أن التغيّرات في الحرز الوسطي للنُظُم الغذائية قد تغيَّر عما كان عليە في خط الأساس تغيراً يُعتَدُّ بە إحصائياً، لدى مقارنة المناطق التي نفذت فيەا التدخلات (والتي أحرزت 2.1+ نقطة) والمناطق الشاەدة (التي أحرزت 1.2- نقطة) وبقيمة احتمال P تقل عن 0.01 كما تغيَّرت النسبة المئوية للأفراد الذين اتبعوا نظاماً غذائياً صحياً، فقد أحرزوا في المناطق التي نفذت فيەا التدخلات +14.9% وفي المناطق الشاەدة -2.0% وبقيمة احتمال تقل عن 0.001. وقد نقص التدخين اليومي بمقدار 0.9% في المناطق التي نفذت فيەا التدخلات وبمقدار 2.6% في المناطق الشاەدة في نەاية السنة الثالثة، إلا أن ەذا الاختلاف ليس لە قيمة يُعتَدُّ بەا إحصائياً. أما التحليل للنتائج بحسب الجنسَيْن فقد أظەر نقصاً يُعتَدُّ بە إحصائياً في الاتجاە إلى التدخين بين الرجال بقيمة احتمال تقل عن 0.05، دون أن ينطبق ذلك على النساء. وقد أظەر بذل الطاقة في مجمل الأنشطة البدنية اليومية اتجاەاً للنقص في جميع المناطق، ولكن متوسط الانخفاض عن خط الأساس كان أقل بشكل يُعتَدُّ بە إحصائياً في المناطق التي نُفِّذت فيەا التدخلات أكثر منە في المنطقة الشاەدة وبلغ النقص في المەام المكافئة الاستقلابية 68 – دقيقة كل أسبوع مقارنة بالنقص في المناطق الشاەدة الذي بلغ 114 – دقيقة كل أسبوع، وبقيمة احتمال تقل عن 0.05. كما ظەر اتجاە لزيادة وقت الترفيە المخصص للأنشطة البدنية في جميع المناطق. ووجدت تغيرات أخرى يُعتَدَّ بەا إحصائياً بين المناطق التي نفذت فيەا التدخلات والمنطقة الشاەدة عما كانت عليە في خط الأساس في كل من حرز (درجة) نمط الحياة، حتى بعد وضع قيم شاەدة للعمر والجنس والقيم الأساسية.

الاستنتاج

تشير النتائج أن برامج التدخلات المجتمعية المرتكز التي تستەدف أنماط الحياة قد تكون فعَّالة في البلدان النامية.

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases currently represent 43% of the global burden of disease and are expected to account for 60% of the disease burden and 73% of all deaths in the world by 2020.1 Most of this increase will reflect non-communicable disease epidemics in developing countries resulting from the epidemiological transition, recent changes in diet and social environment, and the adoption of lifestyles resembling those of developed societies.2–4 In developing countries, lifestyle-related chronic diseases, particularly cardiovascular disease, heavily burden the health-care system.5,6 It has been estimated that an unhealthy diet and physical inactivity alone accounted for approximately 20% of the deaths among adults in the United States of America in 2000,7 and the figures could be even higher in developing countries.4–6 Cross-sectional and prospective studies have shown that the prevalence and incidence of many chronic conditions, including obesity, atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease and certain cancers, are increased by unhealthy lifestyles,8–12 particularly an unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, smoking and stress. Therefore, lifestyle modification, long considered the cornerstone of interventions, is extremely important in reducing the burden of chronic diseases.

Several intervention trials have reported the effects of lifestyle intervention programmes among high-risk populations.13–18 Some have recently shown a 58% decrease in the incidence of diabetes in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance.19,20 Others have reported the beneficial effects of lifestyle modification on blood pressure control.21,22 Lifestyle interventions seem to be at least as effective as drugs.23

Despite the above, recent reviews have cast doubt on whether lifestyle interventions really help reduce multiple cardiac risk factors.24 For developing countries the evidence is less clear, and intervention studies in such countries have been scarce. Moreover, most intervention studies in the developing world have targeted specific population groups, rather than the whole community. In the Islamic Republic of Iran the Isfahan Healthy Heart Program (IHHP), which relies on comprehensive community-based lifestyle interventions to improve diet, physical activity, smoking behaviour and stress management,25 has provided an opportunity to assess whether such interventions really work in developing countries. The specific objective of this study is to evaluate the effects of this comprehensive, integrated community-based lifestyle intervention on diet, physical activity and smoking behaviours.

Methods

Population

The study design and rationale of the intervention methods employed in the IHHP have been described elsewhere.26 In this study, which was initiated in the year 2000, two intervention counties (Isfahan and Najaf-Abad) and a control area (Arak), all located in central Islamic Republic of Iran, were studied. According to the 2000 national census, the population was 1 895 856 in Isfahan and 275 084 in Najaf-Abad, a neighbouring county. Arak, a county with a population of 668 531 located 375 km north-west of Isfahan, was selected as a control area because it resembled the intervention areas in its socioeconomic, demographic and health profile and offered good cooperation.26 The intervention programme targeted the general population as well as specific groups in urban and rural areas within the intervention communities. Arak was monitored for evaluation purposes but did not receive any intervention. In each community, a random sample of adults was selected yearly by multi-stage cluster sampling. To achieve adequate sample size, those who declined to participate in the study were replaced by their neig hbours. Assessments of dietary intake, physical activity and smoking behaviour were made at baseline and annually for up to 4 years in the intervention areas and up to 3 years in the control area. For each annual evaluation, an independent random sample of adult community residents was randomly selected by a multi-stage cluster sampling method (Table 1). Informed written consent was provided by each participant.

Table 1. General characteristics of the study population in a study of the effects of Isfahan Healthy Heart Program interventions on diet, physical activity and smoking behaviour, the Islamic Republic of Iran.

| Characteristic | Baseline | Annual evaluation |

P-value for trend | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | |||||

| n | ||||||||

| Intervention areasa | 6 175 | 2 994 | 2 400 | 3 012 | 3 011 | |||

| Control areab | 6 339 | 2 897 | 2 393 | 3 070 | NA | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| Intervention areas | 38.6 ± 14.7 | 40.4 ± 15.4 | 40.7 ± 15.6 | 45.1 ± 17.3 | 45.6 ± 17.3 | < 0.01 | ||

| Control area | 39.1 ± 15.1 | 40.5 ± 15.3 | 40.5 ± 15.9 | 45.0 ± 17.3 | NA | < 0.01 | ||

| Females (%) | ||||||||

| Intervention areas | 51.3 | 50 | 50.3 | 50.6 | 51.4 | > 0.05 | ||

| Control area | 50.8 | 51 | 50.5 | 51.1 | NA | > 0.05 | ||

| Response rate (%) | ||||||||

| Intervention areas | 98 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 100 | NA | ||

| Control area | 100 | 97 | 99 | 100 | NA | NA | ||

| Place of residence (% rural) | ||||||||

| Intervention areas | 21.0 | 18.5 | 18.7 | 20.3 | 11.9 | < 0.01 | ||

| Control area | 33.4 | 33.3 | 35 | 31 | NA | < 0.05 | ||

NA, not applicable. a Intervention areas: Isfahan and Najaf-Abad. b Control area: Arak.

Interventions

The IHHP conducts integrated activities in health promotion, disease prevention, and health-care treatment and rehabilitation. In all, the programme comprises 10 distinct projects, each targeting different groups. The projects’ target populations and main interventions are listed in Table 2. Key strategies linked to intervention activities include public education through the mass media, inter-sectoral cooperation and collaboration, community participation, education and involvement of health professionals, marketing and organizational development, legislation and policy development or enforcement, and research and evaluation. The IHHP promotes healthy nutrition and increased physical activity and conducts tobacco control and stress management activities. Interventions are targeted to individuals, populations and the environment depending on the results of baseline surveys on diet, physical activity, smoking and stress management and on an assessment of needs in these areas and of their coverage by existing health services. The directors of different interventions work intensively and closely with representatives of the mass media (television, newspapers, radio, etc.), health professionals (administrators, physicians, nurses, health workers and volunteers, social workers, etc.), business and market leaders (from the food industry, groceries, bakeries, fast food shops, etc.), key staff of nongovernmental organizations, and local political decision-makers (county, municipal and provincial leaders). The IHHP’s organization and interventions are described in greater detail elsewhere.27

Table 2. Brief description of the 10 main intervention projects of the Isfahan Healthy Heart Program, the Islamic Republic of Iran.

| Project name | Main interventions |

|---|---|

| Healthy Food for Healthy Community | Educating about healthy cooking methods and making high-fibre, low-salt bread; promoting the production of healthy food products by food industries; modifying food labels; educating the public on the concept of healthy nutrition; improving the formulations in confectioneries; introducing healthy brands and half-portions in restaurants and fast food eateries |

| Isfahan Exercise and Air Pollution Control Project | Providing training on exercise and physical activity through local television; distributing educational CDs about exercise at home and at the worksite; organizing public exercise rallies, automobile-free days and healthy heart exhibitions; educating about air pollution control methods through local television; advocating the development of bicycle lanes in the city |

| Women Healthy Heart Project | Providing healthy lifestyle training to young women attending pre-marriage classes and their family members, as well as instructors of the literacy campaign movement and their students, instructors of charities, women in the Basij Movement (coalitions within mosques), women in different organizations, women attending health centres and health houses, and female volunteer instructors of the Red Crescent Society; educating the public through television and cook books; distributing a CD about methods of physical activity requiring no special facilities |

| Heart Health Promotion from Childhood | Providing healthy lifestyle training to children, parents, health professionals and school and kindergarten staff about healthy lifestyles; promoting physical activity in schools and kindergartens; introducing healthy snacks in schools and kindergartens; establishing healthy buffets in schools; forming role model groups from volunteer students; providing practical training through television about healthy lifestyles; screening for cardiovascular disease risk factors in children of patients with premature cardiovascular disease and in children with at least one risk factor, such as obesity |

| Youth Intervention Project | Providing healthy lifestyle training to volunteers from the Red Crescent Society, garrison instructors, soldiers in their mandatory military service and university students, as well as kitchen staff of universities and garrisons; conducting an international anti-smoking Quit & Win campaign |

| Worksite Intervention Project | Providing healthy lifestyle training to occupational medicine physicians or health assistants; introducing dietary modifications into factory restaurants; enforcing no-smoking regulations at worksites; using the existing screening system to detect high-risk groups; promoting physical activity at worksites; providing health messages about cardiovascular disease prevention in official newsletters of different organizations |

| Non-Governmental Organizations and Volunteers Project | Training health workers in cities and villages; forming, training and empowering an assembly of health volunteers; training community members in performing physical activity in the absence of facilities, healthy nutrition and coping with stress via trained volunteers and health-related nongovernmental organizations |

| Health Professionals Education Project | Establishment of educational assemblies; training general practitioners by continual medical education courses; training physicians through periodical seminars; training nurses by forming educational assemblies; publishing and distributing books and newsletters among nurses and other health professionals in urban and rural areas; running information campaigns on various occasions |

| Health Lifestyle for High-Risk Groups | Providing healthy lifestyle training to health-system personnel, high-risk individuals and retired employees; activating clinics at hospitals; training the public; distributing educational brochures to people attending pharmacies; printing health messages on laboratory report sheets |

| Healthy Lifestyle for Cardiovascular Patients Project | Providing healthy lifestyle training to patients and their families at the time of hospital discharge; printing cards for patients to record all necessary information related to their disease; establishing rehabilitation units at all heart hospitals; improving nutritional and cooking procedures at hospital restaurants; distributing educational folders containing educational materials on cardiovascular-disease secondary prevention and rehabilitation |

Behaviour assessments

Assessments of diet, physical activity and smoking behaviour were performed at baseline (year 2000) and annually for 4 years in the intervention areas and for 3 years in the control area. An insufficient budget made it impossible to collect data in the control area during the fourth year. The usual dietary intake was assessed using a 49-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) listing foods commonly consumed by Iranians and administered by trained technicians. For each food item, participants were asked to report common portion sizes and consumption frequency during the previous year. The latter was recorded in terms of daily (e.g. bread), weekly (e.g. rice, meat) and monthly (e.g. fish) consumption, and the daily intake of each food was derived by dividing weekly consumption by 7 and monthly consumption by 30.

Data on physical activity, expressed as metabolic equivalent task (MET) minutes per week, were obtained through an oral questionnaire that included questions on four activity domains: job-related physical activity; transportation-related physical activity; housework and house maintenance activities; recreation, sport and leisure-time physical activity. We asked participants to think about all the vigorous and moderate activities they had performed in the last 7 days, considering the number of days a week and the time spent on these activities. Additional information regarding age, sex, smoking behaviour, place of residence and educational level was collected using a questionnaire. Several questions on smoking behaviours were asked, with the following key questions used to categorize individuals: “Are you currently smoking (cigarettes, pipe, and hookah)?” and “What is the frequency of smoking in a day, week or month”? We categorized individuals as current smokers if they smoked ≥ 1 times a day. In this study, smoking included the use of cigarettes, a pipe or a hookah.

Definition of low-risk groups

We defined low-risk groups in terms of dietary intake, smoking habits and physical activity. For dietary intake, the 49 food items on the food frequency questionnaire were first classified into 12 food groups, as follows: (i) fruits, (ii) vegetables, (iii) dairy products, (iv) non-hydrogenated vegetable oils, (v) legumes, (vi) nuts, (vii) white meat, (viii) grains, (ix) hydrogenated vegetable oils, (x) red meat, (xi) processed meat, (xii) sweets and pizza. We then quantified participants’ intakes of foods from these groups and divided the participants into quintiles according to their intakes. Individuals in the two highest intake quintiles for fruits, vegetables, dairy products, non-hydrogenated vegetable oils, legumes, nuts and white meat were classified as having a healthy diet and were given a score of 1 for each food group, while those in the lowest, second and third intake quintiles of these food groups were given a score of 0. For unhealthy food groups like grains, hydrogenated vegetable oils, red meat and processed meat, sweets and pizza, the opposite was done: individuals in the lowest and second quintiles were given a score of 1 and those in the three highest quintiles were given a score of 0. All grains were classified as unhealthy because the ones ordinarily consumed in Iran are refined rather than whole. Pizza plus sweets were counted as a single unhealthy food group because both are commonly consumed in Iran and contain harmful fats, such as trans-fats. It was not possible to separate low- and high-fat dairy products because the distinction was not made in the consumption questionnaire, so all dairy products were classified as a single, healthy food group. The total dietary score was calculated as the sum of the scores given for all 12 food groups. Thus, the total dietary score for each individual could vary from 0–12. Individuals whose total dietary score was ≥ 8 were classified as being on a healthy diet and assigned a risk score of 1, whereas those with a dietary score of < 8 were classified as being on a poor diet and assigned a risk score of 0.

For smoking, the low-risk group was defined as being composed of individuals who had stopped smoking or had never smoked. In terms of physical activity, the low-risk group was composed of individuals who spent an average of half an hour per day doing vigorous or moderate exercise. Finally, we summed up the scores for diet (low-risk = 1, others = 0), smoking (low-risk = 1, others = 0) and physical activity (low-risk = 1, others = 0) to come up with a lifestyle score.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 10.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States of America) was used for all statistical analyses. Linear trend analysis of variance was used to compare mean diet scores and MET minutes per week in the three different study sites across different years. The Mantel-Haenszel extension χ² test was used to assess the overall trend for categorical variables. To compare continuous and categorical variables between intervention and control areas, Student’s t test, analysis of covariance (controlling for age, sex and baseline values) and χ² test were used where appropriate. The means of lifestyle score were computed separately by residence area and linear trend analysis of variance was used to assess the overall trend shown by this score across annual evaluations. Cumulative proportions of individuals with different lifestyle scores (0–3) were calculated in different years separately for intervention and control areas.

Results

The characteristics of the study participants in terms of diet, smoking habits and physical activity at baseline and after the intervention in the different sites are presented in Table 3. The baseline mean dietary score in Isfahan and Najaf-Abad (intervention areas) and in Arak (control area) was 4.5, 4.8 and 5.7, respectively. Annual evaluations revealed a significant increasing trend in mean dietary scores in both intervention areas (P for trend < 0.05), but no significant change in the control area (P for trend = 0.41). A similar pattern was seen in the percentage of individuals who ate a healthy diet. In the fourth annual evaluation, almost 40% of all individuals in Isfahan (as compared to 18% at baseline, P for trend < 0.01) and 31% in Najaf-Abad (as compared to 14% at baseline, P for trend < 0.01) ate healthy diets, while no significant trend was observed in Arak (almost 11% in the third annual evaluation as compared to 13% at baseline, P for trend = 0.38). With regard to smoking, a significant decreasing trend was seen in Isfahan (P for trend < 0.001) but not in Najaf-Abad (P for trend = 0.21). Although, a significant decreasing trend (P = 0.004) was also evident in the control area, the percentage of daily smokers in the first and second yearly evaluations was not significantly different from baseline.

Table 3. Characteristics of study participants in terms of diet, smoking habits and physical activity before and after lifestyle interventions in a study of the effects of the Isfahan Healthy Heart Program, the Islamic Republic of Iran.

| Study area | Baseline | Annual evaluation |

P-value for trend | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | |||||

| Isfahan | ||||||||

| n | 4 187 | 2 098 | 1 680 | 2 004 | 2 003 | |||

| Dietary scorea (mean ± SD) | 4.5 ± 1.6 | 5.1 ± 1.6 | 5.7 ± 1.6 | 6.3 ± 1.4 | 6.9 ± 1.7 | < 0.05 | ||

| Healthy dietb (%) | 18.3 | 18.9 | 26.4 | 33.6 | 39.8 | < 0.01 | ||

| Daily smokers (%) | 14.7 | 15.1 | 12.9 | 13.6 | 11.7 | < 0.001 | ||

| Total daily physical activity (MET-m/week) | 856 ± 546 | 763 ± 517 | 756 ± 601 | 617 ± 540 | 682 ± 734 | < 0.001 | ||

| Leisure time physical activity (MET-m/week) | 86 ± 93 | 83 ± 79 | 104 ± 78 | 122 ± 275 | 157 ± 350 | < 0.001 | ||

| Individuals (%) with ≥ 30 minutes/day moderate or vigorous activity | 50.3 | 37.1 | 50.3 | 28.2 | 40.7 | < 0.001 | ||

| Najaf-Abad | ||||||||

| n | 1 988 | 896 | 720 | 1 008 | 1 008 | |||

| Dietary scorea (mean ± SD) | 4.8 ± 1.3 | 5.9 ± 1.4 | 6.2 ± 1.7 | 7.4 ± 1.7 | 7.5 ± 1.6 | < 0.05 | ||

| Healthy diet (%) | 14.2 | 15.7 | 19.6 | 28.4 | 31.3 | < 0.01 | ||

| Daily smokers (%) | 15.1 | 15.0 | 9.4 | 14.6 | 13.9 | 0.21 | ||

| Total daily physical activity (MET-m/week) | 946 ± 657 | 898 ± 526 | 923 ± 602 | 881 ± 697 | 852 ± 772 | 0.002 | ||

| Leisure time physical activity (MET-m/week) | 81 ± 87 | 79 ± 69 | 93 ± 64 | 178 ± 288 | 181 ± 382 | < 0.001 | ||

| Individuals (%) with ≥ 30 minutes/day moderate or vigorous activity | 40.1 | 28.9 | 40.0 | 43.3 | 40.7 | 0.010 | ||

| Arak | ||||||||

| n | 6 339 | 2 897 | 2 393 | 3 070 | NA | |||

| Dietary scorea (mean ± SD) | 5.7 ± 1.5 | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 4.5 ± 1.6 | NA | 0.41 | ||

| Healthy diet (%) | 12.8 | 14.4 | 13.9 | 10.8 | NA | 0.38 | ||

| Daily smokers (%) | 15.2 | 16.3 | 15.3 | 12.6 | NA | 0.004 | ||

| Total daily physical activity (MET-m/week) | 898 ± 530 | 810 ± 442 | 777 ± 486 | 641 ± 547 | NA | < 0.001 | ||

| Leisure time physical activity (MET-m/week) | 84 ± 90 | 74 ± 63 | 91 ± 58 | 119 ± 198 | NA | < 0.001 | ||

| Individuals (%) with ≥ 30 minutes/day moderate or vigorous activity | 46.8 | 24.0 | 32.0 | 31.1 | NA | < 0.001 | ||

MET-m/week, metabolic equivalent task minutes per week; NA, not available; SD, standard deviation. a Dietary score was calculated by summing up the scores given to participants based on quintile cut-points based on consumption of items in 12 food groups. b Individuals with a total dietary score of ≥ 8 were considered to be on a healthy diet.

Data on energy expenditure for total daily physical activity showed a significant decreasing trend in both intervention areas (P for trend was < 0.001 in Isfahan, 0.002 in Najaf-Abad) and in the control area (P for trend < 0.001). However, the opposite trend was noted in energy expenditure for leisure time physical activity, both in the intervention areas and in the control area. A decreasing trend was also found in the percentage of individuals with ≥ 30 minutes of moderate or vigorous physical activity a day in all areas (P < 0.01 for all areas). The findings were almost the same when the data were analysed separately by gender.

A comparison of lifestyle variables between intervention and control areas showed that at baseline the mean dietary score was significantly lower in the intervention areas than in the control area (4.6 versus 5.7; P < 0.01). In contrast, the percentage of individuals on a healthy diet was significantly higher in the intervention areas than in the control area (16.9 versus 12.8%, respectively; P < 0.05). Other variables did not differ significantly between intervention and control areas at baseline (Table 4), even when the data were analysed separately by gender.

Table 4. Diet, physical activity and smoking in Isfahan and Najaf-Abad (intervention areas) and Arak (control area) before and after lifestyle interventions in a study of the effects of the Isfahan Healthy Heart Program, the Islamic Republic of Iran.

| Behaviour | Baseline | Annual evaluation |

P-value for trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |||||

| n | |||||||

| Intervention areas | 6 175 | 2 994 | 2 400 | 3 012 | |||

| Control area | 6 339 | 2 897 | 2 393 | 3 070 | |||

| Mean dietary scorea ± SD | |||||||

| Intervention areas | 4.6 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ± 1.5 | 5.9 ± 1.6 | 6.7 ± 1.5 | < 0.05 | ||

| Control area | 5.7 ± 1.5 | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 4.5 ± 1.6 | 0.41 | ||

| P-value | < 0.01 | < 0.05 | 0.24 | < 0.01 | |||

| Healthy dietb (%) | |||||||

| Intervention areas | 16.9 | 17.7 | 24.3 | 31.8 | < 0.01 | ||

| Control area | 12.8 | 14.4 | 13.9 | 10.8 | 0.38 | ||

| P-value | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.01 | < 0.001 | |||

| Daily smokers (%) | |||||||

| Intervention areas | 14.8 | 15.0 | 11.9 | 13.9 | < 0.05 | ||

| Control area | 15.2 | 16.3 | 15.3 | 12.6 | 0.004 | ||

| P-value | 0.63 | 0.24 | < 0.05 | 0.09 | |||

| Total daily physical activity (MET-m/week ± SD) | |||||||

| Intervention areas | 606 ± 402 | 570 ± 396 | 550 ± 381 | 538 ± 391 | < 0.01 | ||

| Control area | 620 ± 398 | 629 ± 393 | 603 ± 411 | 506 ± 361 | < 0.01 | ||

| P-value | 0.04 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | |||

| Leisure time physical activity (MET-m/week ± SD) | |||||||

| Intervention areas | 85 ± 91 | 82 ± 76 | 104 ± 74 | 120 ± 160 | < 0.01 | ||

| Control area | 84 ± 90 | 74 ± 63 | 91 ± 58 | 106 ± 147 | < 0.01 | ||

| P-value | 0.70 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | |||

| Individuals (%) with ≥ 30 minutes/day of moderate or vigorous activity | |||||||

| Intervention areas | 47.0 | 34.6 | 47.2 | 33.2 | < 0.01 | ||

| Control area | 46.8 | 24.0 | 32.0 | 31.1 | < 0.001 | ||

| P-value | 0.93 | < 0.05 | < 0.01 | 0.11 | |||

MET-m/week, metabolic equivalent task minutes per week; SD, standard deviation. a Dietary score was calculated by summing up the scores given to participants based on quintile cut-points based on consumption of items in 12 food groups. b Individuals on a healthy diet were considered as those having a total diet score of ≥ 8.

Mean lifestyle scores at baseline and at each annual evaluation are shown in Fig. 1. Residents of Isfahan had a slightly better mean lifestyle score at baseline than did residents of Najaf-Abad and Arak (1.32 versus 1.22 and 1.23, respectively, P < 0.05). Following lifestyle interventions, the mean lifestyle score increased progressively in Isfahan (from baseline to the fourth annual evaluation: 1.32, 1.44, 1.57, 1.69, 1.72, respectively; P for trend < 0.05) and in Najaf-Abad (1.22, 1.31, 1.49, 1.56, 1.69, respectively; P for trend < 0.05), but not in Arak (from baseline to the third annual evaluation: 1.23, 1.17, 1.24, 1.25, respectively; P for trend = 0.15). A significantly greater change from baseline in mean lifestyle score was noted in the intervention areas when compared to the control area, even after controlling for age, sex and baseline values (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Mean lifestyle scorea in Isfahan and Najaf-Abad (intervention areas) and Arak (control area) before and after lifestyle interventions in a study of the effects of the Isfahan Healthy Heart Program, the Islamic Republic of Iran

a The lifestyle score is the mean of the sum of the scores for diet (low-risk = 1, others = 0), smoking (low-risk = 1, others = 0) and physical activity (low-risk = 1, others = 0). Residents of Isfahan had a slightly healthier lifestyle at baseline than did residents of Najaf-Abad and Arak.

After the lifestyle intervention, changes from baseline in mean dietary score were significantly different between intervention and control areas (+2.1 points versus –1.2 points, respectively; P < 0.01). Similarly, the change from baseline in the percentage of individuals who ate a healthy diet differed significantly between the intervention and control areas (+14.9% versus –2.0%, respectively; P < 0.001). Covariance analysis after controlling for sex, age, and baseline values yielded the same findings.

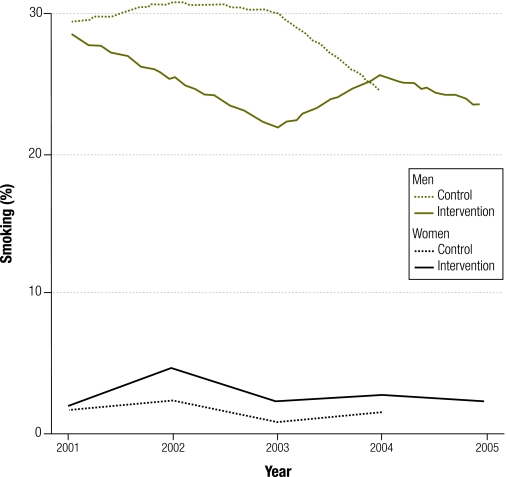

Daily smoking decreased in both intervention and control areas after the lifestyle intervention, but the changes from baseline were not significantly different between areas. When genders were analysed separately, a significant decreasing trend was found among men, but not among women (Fig. 2). Although changes from baseline in energy expenditure for both total daily physical activities and leisure time physical activities were in a downward and upward direction, respectively, when intervention and control areas were compared, mean changes from baseline in total daily physical activities were significantly lower in the intervention areas than in the control area (–68 versus –114 MET minutes per week; P < 0.05). Such findings were obtained even after adjusting for age, sex and baseline values. No significant difference was seen in the percentage of individuals with ≥ 30 minutes a day of moderate or vigorous physical activity between intervention and control areas after 4 years of the lifestyle intervention. However, in the first and second annual evaluations, participants in the intervention areas were more likely to engage in such activity.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of daily smoking, by gender, in Isfahan and Najaf-Abad (intervention areas) and in Arak (control area) before and after lifestyle interventions in a study of the effects of the Isfahan Healthy Heart Program, the Islamic Republic of Iran

The percentage of individuals with different lifestyle scores in intervention and control areas is presented in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4. At baseline, 8.7% of the individuals in the intervention areas had a lifestyle score of 0 (unhealthy lifestyle), whereas only 3.6% had a score of 3 (healthy lifestyle). In these areas, the percentage of individuals with an unhealthy lifestyle was lower after the lifestyle intervention, while the percentage of individuals with a healthy lifestyle was higher. Thus, by the fourth yearly evaluation almost two-thirds of the population had at least two (out of three) healthy lifestyle components. Such a trend was not so clear in the control area; however, the percentage of individuals with a score of 3 had increased significantly by the third evaluation as compared to baseline (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of individuals with different lifestyle scoresa in Isfahan and Najaf-Abad (intervention areas) before and after lifestyle interventions in a study of the effects of the Isfahan Healthy Heart Program, the Islamic Republic of Iran

a The lifestyle score is the sum of the scores for diet (low-risk = 1, others = 0), smoking (low-risk = 1, others = 0) and physical activity (low-risk = 1, others = 0).

Fig. 4.

Percentage of individuals with different lifestyle scoresa in Arak (control area) before and after lifestyle interventions in a study of the effects of the Isfahan Healthy Heart Program, the Islamic Republic of Iran

a The lifestyle score is the sum of the scores for diet (low-risk = 1, others = 0), smoking (low-risk = 1, others = 0) and physical activity (low-risk = 1, others = 0).

Discussion

The findings of the present study, which was performed in a representative sample of the Iranian population, suggest that lifestyle habits can be improved by a community-based lifestyle intervention programme even in a developing country setting. After the comprehensive, integrated community-based lifestyle intervention programme, beneficial changes were noted in diet and physical activity but no substantial changes were seen in the smoking behaviour of the population, particularly among women. Total lifestyle scores and the percentage of individuals with a healthy lifestyle increased significantly in the intervention areas. The approaches followed in the IHHP closely resemble those of the North Karelia project in Finland, since both projects were controlled comprehensive, community-based interventions targeting the general population and the environment. Although Finland is not a developing country, the North Karelia project was originally carried out in fairly low-resource, semi-rural settings.

Although assessing the effects of comprehensive lifestyle intervention programmes on diet, physical activity and smoking behaviours is not new, few reports are available from developing countries.28–30 Most integrated community-based programmes have been carried out in developed countries; however, a remarkably rapid increase in the burden of non-communicable diseases in developing countries has made researchers in these places undertake similar activities. Several lifestyle interventions have been carried out in these countries.3,28–33 The major limitations of previous reports from developing countries have been the lack of a control area,28 the lack of annual and process evaluations, and a focus on risk factor prevalence rather than on actual changes in diet, physical activity and smoking habits.29,30 Therefore, it is not clear to what extent the changes documented in this study represent the effect of the intervention as opposed to underlying secular trends. Through comparing changes from baseline in diet, physical activity and smoking behaviour in intervention areas and in a control area, the present study shows that lifestyle interventions can work in developing countries.

Community-based lifestyle interventions have been conducted with varying results. Some have documented beneficial changes in respondents’ dietary habits;22,34 others have failed to document such changes.35 In this study, the most pronounced change from baseline after the IHHP lifestyle intervention programme was noted in the dietary habits of intervention area residents. The mean dietary score and percentage of individuals following a healthy diet increased significantly in areas where the lifestyle intervention programme was in place. Previous reports from the IHHP have also suggested that the lifestyle interventions encouraged people to choose healthy foods and prompted government authorities to make them available. Thus, policy changes in the framework of the IHHP intervention programme were such that between 2000 (baseline) and 2002, the distribution of hydrogenated and non-hydrogenated vegetable oils in intervention areas changed from 82% to 68% and from 18% to 32%, respectively, while in the control area it changed from 97% to 95% and from 3% to 5%, respectively.25,26 A decline in salt intake has also been reported in the intervention areas.25 All these data suggest that dietary habits have been affected by the IHHP intervention programme. However, in this study the consumption of specific nutrients or foods was not assessed because it was felt that the multivariate, whole diet approach would provide more information and eliminate concerns about confounding factors and co-linearity in food and nutrient intakes. Dietary changes across the population have been noted for as long as 20 years after the cessation of lifestyle modification programmes.36 Although the direct and independent effects of such beneficial dietary changes on the risk of non-communicable diseases in the target population are relatively unknown, it has been suggested that a relatively small shift towards a healthier diet in the entire population may lead to a reduction in the incidence of non-communicable diseases.37,38 The fact that in this study the most prominent changes from baseline were found in dietary habits is in line with findings reported from North Karelia,39,40 where half of the decline in mortality from coronary disease since 1972 can be explained by dietary changes across the population.39

The energy expended for total daily physical activity declined in both intervention and control areas but was less pronounced in the former than in the latter. However, the energy expended for leisure time physical activity increased in both areas, and much more so in the intervention areas than in the control area. Therefore, if the physical activity levels in the control area are assumed to be representative of the secular trend, one can conclude that the IHHP lifestyle intervention programme influenced physical activity levels in the target populations, albeit not substantially. Other community-based programmes have not been accompanied by substantial changes in physical activity, although the prevalence of physical inactivity might have decreased.41,42 However, some intensive programmes have been accompanied by improved maximum oxygen uptake,18 increased time spent on physical activities20,34 and reduced physical inactivity.34 Promoting physical activity calls not only for educating the target population, but often also for expensive facilities that can seldom be afforded by a research programme, particularly in a developing country,38 because many people mistakenly consider them necessary. Cultural factors that may hinder physical activity must also be taken into account.38

Community-based lifestyle intervention programmes have been associated in varying degrees with improvements in smoking behaviour in target populations.14,43 In the current study, daily smoking decreased in both the intervention areas and the control area after 3 years of lifestyle intervention, although changes from baseline were not significantly different between these two areas. Previous short-term reports from the IHHP have shown a significant effect of lifestyle interventions among men but not women,25 which points to the need to modify interventional activities in this group. In this study, the percentages of daily smokers in the control area in the first and second yearly evaluations were not significantly different from baseline, and there was a significant difference in changes from baseline between the intervention and control areas after 2 years of the intervention. This is in line with other studies and highlights the fact that long-term control of smoking is very difficult to attain. While various programmes have been accompanied by increased attempts at quitting and have moved participants towards being ready to quit, very few programmes have influenced long-term cessation rates.43,44 Any change that affects the prevalence of smoking in a community is also likely to affect community norms, which will in turn lead to even greater change in the community. Bringing about a shift of this kind, however, is not a trivial goal and usually requires more time than research projects allow.45–47 These results serve to underscore the addictive properties of nicotine and suggest that long-term behavioural interventions and ongoing counselling may be required to influence cessation. As little evidence exists to support the effectiveness of any specific intervention on long-term cessation rates, further studies are needed to advance this field.

Several points need to be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. First, the effect of lifestyle interventions on risk factor prevalence has not been examined in the current study; data from the annual evaluations was used to document changes in the population’s behaviour. To what extent the IHHP lifestyle interventions have affected biochemical measures and biological risk factors will be assessed in the post-intervention phase of the study. Second, methodological differences between community-based intervention programmes might explain to some extent the observed differences in lifestyle changes from baseline. Third, although lifestyle interventions for the primary prevention of non-communicable diseases are cost-effective according to previous reports,48 this would differ among countries because of country-specific intervention costs.49

The high response rates in our study can be explained by the fact that the samples for different years were independent and that the authors followed the whole community, not just the same individuals who comprised the sample in the first year of the study. Because of this, the response rate in this study is higher than is commonly found in cohort studies. Another reason is that free services were provided to study participants. In the invitation letters to residents, it was highlighted that all medical services would be free for participants, even if these involved additional medical consultations and expensive treatments. This point is important in developing countries like the Islamic Republic of Iran, where many are barely able to afford medical services.

In conclusion, comprehensive community-based lifestyle interventions, even in developing countries, can change the environment of the entire community to support healthier lifestyles. This would reduce health-risk behaviours, which would in turn decrease chronic disease morbidity and mortality. ■

Footnotes

Funding: The Isfahan Cardiovascular Research Center funded the project.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367:1747–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Mortality by cause for eight regions of the world: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1269–76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Critchley J, Liu J, Zhao D, Wei W, Capewell S. Explaining the increase in coronary heart disease mortality in Beijing between 1984 and 1999. Circulation. 2004;110:1236–44. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140668.91896.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO global strategy for NCD prevention and control: report by Director General Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000 (WHO/WHA/53).

- 5.The world health report 2002: reducing risks, promoting healthy life Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000 (WHO Technical Report Series 894). [PubMed]

- 7.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature. 2001;414:782–7. doi: 10.1038/414782a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kromhout D, Menotti A, Kesteloot H, Sans S. Prevention of coronary heart disease by diet and lifestyle: evidence from prospective cross-cultural, cohort, and intervention studies. Circulation. 2002;105:893–8. doi: 10.1161/hc0702.103728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belpomme D, Irigaray P, Sasco AJ, Newby JA, Howard V, Clapp R, et al. The growing incidence of cancer: role of lifestyle and screening detection. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:1037–49. doi: 10.3892/ijo.30.5.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz G, Liu S, Solomon CG, et al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:790–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stampfer MJ, Hu FB, Manson JE, Rimm EB, Willett WC. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women through diet and lifestyle. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:16–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007063430103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mattila R, Malmivaara A, Kastarinen M, Kivelä SL, Nissinen A. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention for hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17:199–205. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nilsson P, Klasson EB, Nyberg P. Lifestyle intervention at the worksite: reduction of cardiovascular risk factors in a randomized study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2001;27:57–62. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muto T, Yamauchi K. Evaluation of a multicomponent workplace health promotion program conducted in Japan for improving employees’ cardiovascular disease risk factors. Prev Med. 2001;33:571–7. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irwin ML, Yasui Y, Ulrich C, Bowen D, Rudolph R, Schwartz R. Effect of exercise on total and intra-abdominal body fat in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:323–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duncan GE, Perri M, Theriaque D, Hutson A, Eckel R, Stacpoole P. Exercise training, without weight loss, increases insulin sensitivity and postheparin plasma lipase activity in previously sedentary adults. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:557–62. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eriksson KF, Lindgärde F. Prevention of type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus by diet and physical exercise: The 6-year Malmö feasibility study. Diabetologia. 1991;34:891–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00400196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson J, Valle T, Hamalainen H, Parikka P. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler S, Hamman R, Lachin J, Walker E, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, Cooper LS, Obarzanek E, Elmer PJ, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2083–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elmer PJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Simons-Morton D, Stevens VJ, Young DR, et al. PREMIER Collaborative Research Group. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on diet, weight, physical fitness, and blood pressure control: 18-month results of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:485–95. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gillies CL, Abrams KR, Lambert PC, Cooper NJ, Sutton AJ, Hsu RT, et al. Pharmacological and lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;334:299. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39063.689375.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ebrahim S, Beswick A, Burke M, Davey Smith G. Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD001561. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001561.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarrafzadegan N, Baghaei AM, Sadri GH, Kelishadi R, Malekafzali H, Boshtam M, et al. Isfahan Healthy Heart Program: evaluation of comprehensive, community-based interventions for non-communicable disease prevention. Prev Control. 2006;2:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.precon.2006.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarraf-zadgan N, Sadri G, Malek Afzali H, Baghaei M, Mohammadi Fard N, Shahrokhi S, et al. Isfahan Healthy Heart Program: a comprehensive integrated community-based program for cardiovascular disease prevention and control. Design, methods and initial experience. Acta Cardiol. 2003;58:309–20. doi: 10.2143/AC.58.4.2005288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarrafzadegan N, Baghaei AM, Kelishadi R, Rabiei K, Sadri GH, Talaei M. First annual evaluation of Isfahan Healthy Heart Program (IHHP): full report 2004. Available from: http://74.125.39.104/search?q=cache:N9zP2gD3WWEJ:ihhp.mui.ac.ir [accessed on 24 October 2008].

- 28.Dowse GK, Gareeboo H, Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Tuomilehto J, Purran A, et al. Changes in population cholesterol concentrations and other cardiovascular risk factor levels after five years of the non-communicable disease intervention programme in Mauritius. BMJ. 1995;311:1255–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7015.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhalla V, Fong CW, Chew SK, Satku K. Changes in the levels of major cardiovascular risk factors in the multi-ethnic population in Singapore after 12 years of a national non-communicable disease intervention programme. Singapore Med J. 2006;47:841–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tian HG, Guo ZY, Hu G, Yu SJ, Sun W, Pietinen P, et al. Changes in sodium intake and blood pressure in a community-based intervention project in China. J Hum Hypertens. 1995;9:959–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker DR, Assaf AR. Community interventions for cardiovascular disease. Prim Care. 2005;32:865–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossouw JE, Jooste PL, Chalton DO, Jordaan ER, Langenhoven ML, Jordaan PC, et al. Community-based intervention: the Coronary Risk Factor Study (CORIS). Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22:428–38. doi: 10.1093/ije/22.3.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nissinen A, Berrios X, Puska P. Community-based non-communicable disease interventions: lessons from developed countries for developing ones. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:963–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindstrom J, Louheranta A, Mannelin M, Rastas M, Salminen V, Eriksson J, et al. Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS): lifestyle intervention and 3-year results on diet and physical activity. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3230–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.12.3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arao T, Oida Y, Maruyama C, Mutou T, Sawada S, Matsuzuki H, et al. Impact of lifestyle intervention on physical activity and diet of Japanese workers. Prev Med 2007 May 21; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Ellingsen I, Hjerkinn EM, Arnesen H, Seljeflot I, Hjermann I, Tonstad S. Follow-up of diet and cardiovascular risk factors 20 years after cessation of intervention in the Oslo Diet and Antismoking Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:378–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simmons RK, Harding AH, Jakes RW, Welch A, Wareham NJ, Griffin SJ. How much might achievement of diabetes prevention behavior goals reduce the incidence of diabetes if implemented at the population level? Diabetologia. 2006;49:905–11. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diet, physical activity and health Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002 (WHO/WHA/A55/016).

- 39.Vartiainen E, Puska P, Pekkanen J, Tuomilehto J, Jousilahti P. Changes in risk factors explain changes in mortality from ischaemic heart disease in Finland. BMJ. 1994;309:23–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6946.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pietinen P, Vartiainen E, Seppänen R, Aro A, Puska P. Changes in diet in Finland from 1972 to 1992: impact on coronary heart disease risk. Prev Med. 1996;25:243–50. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brownson RC, Smith CA, Pratt M, Mack NE, Jackson-Thompson J, Dean CG, et al. Preventing cardiovascular disease through community-based risk reduction: the Bootheel Heart Health Project. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:206–13. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.86.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Loughlin JL, Paradis G, Gray-Donald K, Renaud L. The impact of a community-based heart disease prevention program in a low-income, inner-city neighborhood. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1819–26. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.12.1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Secker-Walker RH, Gnich W, Platt S, Lancaster T. Community interventions for reducing smoking among adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3:CD001745. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moher M, Hey K, Lancaster T. Workplace interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD003440. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003440.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Puska P, Nissinen A, Salonen JT, Toumilehto J. Ten years of the North Karelia Project: results with community-based prevention of coronary heart disease. Scand J Soc Med. 1983;11:65–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.COMMIT Research Group Community Intervention Trial for Smoking Cessation (COMMIT): I. cohort results from a four-year community intervention. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:183–92. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.85.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacobs-van der Bruggen MA, Bos G, Bemelmans WJ, Hoogenveen RT, Vijgen SM, Baan CA. Lifestyle interventions are cost-effective in people with different levels of diabetes risk: results from a modeling study. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:128–34. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vijgen SM, Hoogendoorn M, Baan CA, de Wit GA, Limburg W, Feenstra TL. Cost effectiveness of preventive interventions in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic literature review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24:425–41. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200624050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palmer AJ, Roze S, Valentine WJ, Spinas GA, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ. Intensive lifestyle changes or metformin in patients with impaired glucose tolerance: modeling the long-term health economic implications of the diabetes prevention program in Australia, France, Germany, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Clin Ther. 2004;26:304–21. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(04)90029-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]