Abstract

A 60-year-old man presented with congestive heart failure and was diagnosed with cor triatriatum after echocardiography. The various imaging modalities used for the definitive diagnosis of this condition are reviewed.

Keywords: Atrial flutter, Congestive heart failure, Cor triatriatum

Abstract

Une échocardiographie a révélé un cœur triatrial chez un homme de 60 ans atteint d’insuffisance cardiaque. Les auteurs analysent les diverses modalités d’imagerie utilisées pour parvenir au diagnostic définitif.

Cor triatriatum is a rare congenital anomaly, accounting for 0.1% of congenital heart disease (1). Classic cor triatriatum is characterized by a common pulmonary venous chamber separated from the true left atrium inferiorly by a fibromuscular membrane. The membrane is fenestrated to allow blood flow into the left atrium. The natural history of the defect is dependent on the size of the fenestration. If the opening is small, infants with this defect are critically ill and die at a young age. If the opening is larger, patients may present in childhood or young adulthood with a clinical picture similar to that of mitral stenosis.

We describe a case of a man who was diagnosed with cor triatriatum sinister after an echocardiogram was performed for presentation with congestive heart failure. We also review the various imaging modalities used for a definitive diagnosis of this condition.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 60-year-old obese man presented to the emergency room after six weeks of increasing fatigue and shortness of breath on exertion. Medical history was significant for adult-onset diabetes mellitus, hypercholesteremia and asthma.

On physical examination, he was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 140/80 mmHg and a heart rate of 150 beats/min. His respiratory rate was 20 breaths/min with an oxygen saturation of 95% on 2 L of oxygen. There was jugular venous distension. A cardiovascular examination revealed first and second sounds, and a 2/6 holosystolic murmur heard best at the cardiac apex, with radiation to the axilla. On lung auscultation, there were bilateral crackles at the bases. No pedal edema was noted.

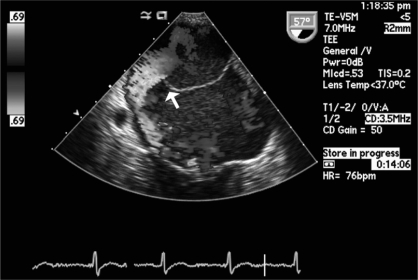

Complete blood count, chemistry panel and cardiac enzymes were within normal limits. B-type natriuretic peptide was elevated, at 743 ng/L (normal range: 0 ng/L to 100 ng/L). An electrocardiogram on admission revealed atrial flutter with a ventricular rate of 150 beats/min. Chest radiographs showed bilateral infiltrates consistent with congestive heart failure. A transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated cor triatriatum sinister (Figure 1). There was evidence of degenerative mitral valve disease with moderate mitral insufficiency. Left ventricular systolic function was 60%. The patient underwent electrical cardioversion to normal sinus rhythm. He was also initiated on intravenous furosemide, to which he responded well. Right-heart catheterization revealed a mean right atrial pressure of 17 mmHg, right ventricular pressure of 44/21 mmHg, pulmonary artery pressure of 40/23 mmHg and mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of 28 mmHg. His left ventricular end-diastolic pressure was 25 mmHg. There was a 10 mmHg gradient between the pulmonary capillary wedge and left ventricular pressures. His cardiac index was 3.0 L/min/m2. Coronary artery catheterization revealed nonobstructive coronary artery disease. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) showed isolated membranous cor triatriatum with a single orifice that measured 1.2 cm (Figure 2). No other congenital abnormalities were noted. Magnetic resonance imaging of the heart was performed, and showed cor triatriatum with posterior inferior fenestrations allowing for blood flow between the anterior and posterior chambers of the heart (Figure 3).

Figure 1).

Transthoracic echocardiography showing cor triatriatum (arrow)

Figure 2).

Transesophageal echocardiography showing an isolated membranous cor triatriatum with a single orifice (arrow) and mitral regurgitation

Despite optimal medical therapy, the patient had multiple episodes of heart failure exacerbations. He eventually underwent successful resection of cor triatriatum with mitral valve annuloplasty. Nine months after surgery, he continued to do well.

DISCUSSION

Cor triatriatum is a rare condition first described by Church in 1868 (2). The embryological origin of this condition is still a controversial subject. Three theories have been suggested: malseptation (the septum subdividing the left atrium is the result of an abnormal overgrowth of septum primum), entrapment (the left horn of the sinus venosus entraps the common pulmonary vein and prevents its incorporation into the left atrium) and malincorporation (incomplete incorporation of the common pulmonary vein into the left atrium). Associated cardiac anomalies include atrial septal defects, mitral regurgitation and partial anomalous venous return.

Communication between the two chambers usually occurs through a perforation. The opening may be small, large, multiple, central or eccentric. Generally, patients are symptom-free, and the diameter of perforation is smaller than 1 cm. The proposed mechanisms for late conversion to a symptomatic state include fibrosis and calcification in the orifice of the separating diaphragm, development of mitral regurgitation, and onset of atrial flutter or fibrillation with rapid ventricular response.

The clinical presentation may be confused with mitral stenosis, supravalvular mitral ring, left atrial thrombus or pulmonary venous stenosis. These entities share the common pathophysiology of obstruction to the flow between the pulmonary venous system and the left ventricle (2). A supravalvular mitral ring is distinguished from cor triatriatum by its position inferior to the left atrial appendage. Definitive diagnosis may be established by two-dimensional (2D) echocardiography, contrast echocardiography, three-dimensional echocardiography, TEE, cardiac catheterization or magnetic resonance imaging. While a 2D echocardiogram may show the membrane, it may not be able to clarify the presence of a left atrial thrombus or myxoma, and may miss very small openings in the fibromuscular membrane. Modi et al (3) described a case of cor triatriatum in which 2D echocardiography, high-resolution computed tomography and multi-planar TEE were unable to demonstrate the opening. Contrast echocardiography, however, showed differential opacification of the two chambers leading to the diagnosis. Similarly, Baweja et al (4) described a case of cor triatriatum associated with a common atrium that masked the associated atrioventricular septal defect on both 2D transthoracic echocardiography and TEE. However, three-dimensional TEE helped make the correct diagnosis by demonstrating complete lack of an atrial septum and the presence of a membrane, with an opening separating the pulmonary veins from the atrium inferiorly. Magnetic resonance imaging is also an excellent modality for evaluating this condition. However, it does not provide any hemodynamic data, and its use is limited by cost and availability.

The definitive treatment for symptomatic patients is surgical excision, although successful balloon catheter dilation of the communication between proximal and distal chambers has been described (5). Because cor triatriatum can remain asymptomatic until late adulthood, it is reasonable to observe patients with an incidental diagnosis, provided that the opening of the diaphragm is nonrestrictive and regular follow-up is possible.

The present case demonstrates the use of different modalities to evaluate cor triatriatum; each modality has its own limitation. In most cases, more than one diagnostic imaging modality is necessary to come to a definitive conclusion.

Figure 3).

Magnetic resonance imaging of the heart showing cor triatriatum (arrow) with fenestration allowing for blood flow between the anterior and posterior chambers of the heart

REFERENCES

- 1.Niwayama G. Cor triatriatum. Am Heart J. 1960;59:291–317. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(60)90287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Church WS. Congenital malformation of the heart: Abnormal septum in left auricle. Trans Pathol Soc (Lond) 1868;19:188–90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Modi KA, Annamali S, Ernest K, Pratep CR. Diagnosis and surgical correction of cor triatriatum in an adult: Combined use of transesophageal and contrast echocardiography, and a review of literature. Echocardiography. 2006;23:506–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2006.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baweja G, Nanda NC, Kirklin JK. Definitive diagnosis of cor triatriatum with common atrium by three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography in an adult. Echocardiography. 2004;21:303–6. doi: 10.1111/j.0742-2822.2004.03095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papagiannis J, Harrison JK, Hermiller JB, et al. Use of balloon occlusion to improve visualization of anomalous pulmonary venous return in an adult with cor triatriatum. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1992;25:323–6. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810250415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]