Abstract

The chiral ligand (−)-sparteine and PdCl2 catalyze the enantioselective oxidation of secondary alcohols to ketones and thus effect a kinetic resolution. The structural features of sparteine that led to the selectivity observed in the reaction were not clear. Substitution experiments with pyridine derivatives and structural studies of the complexes generated were carried out on (sparteine)PdCl2 that indicate the C1 symmetry of (−)-sparteine is essential to the location of substitution at the metal center. Palladium alkoxides were synthesized from secondary alcohols that are relevant steric models for the kinetic resolution. The solid state structures of the alkoxides also confirmed the results from the pyridine derivative substitution studies. A model for enantioinduction was developed with C1 symmetry and Cl− as key features. Further studies of the diastereomers of (−)-sparteine, (−)-α-iso- and (+)-β-isosparteine in the kinetic resolution showed that these C2-symmetric counterparts are inferior ligands in this stereoablative reaction.1

Introduction

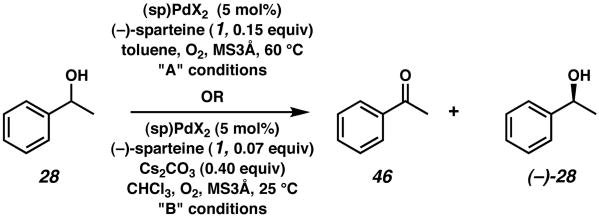

Palladium-catalyzed aerobic oxidation has been known for nearly a century since the discovery by Wieland that this metal could convert alcohols to aldehydes in aqueous media.2 Modern developments to this reaction were initiated in 1977 by Schwartz and Blackburn, who reported that palladium(II) acetate and sodium acetate could aerobically oxidize alcohols to carbonyl compounds.3,4 More recently, our laboratory has developed the enantioselective aerobic oxidation of secondary alcohols by palladium(II) and (−)-sparteine (1).5,6 An example of this transformation is shown in Scheme 1. While numerous improvements to oxidative kinetic resolution have been made, and the mechanism has been analyzed kinetically,6a,e,7 there had been no reports detailing a structural model for asymmetric induction by (−)-sparteine (1) in these reactions. We recently communicated such a model, which was subsequently verified by calculations.8,9 Herein, we describe in full the experiments that support our model for the absolute stereochemical outcome. This model is based on the reactivity and solid state structures of a series of palladium(II) complexes, including the first reported structures of chiral palladium alkoxides relevant to this system. New studies of the diastereomers of (−)-sparteine (1) and of another catalyst precursor lend further support to our model, and highlight the alkaloid (−)-sparteine (1) as an atypical c chiral ligand.

Scheme 1.

a nbd = norbornadiene. 0.1 M in toluene. 5 mol % Pd(nbd)Cl2.

Since the development of the oxidative kinetic resolution of secondary alcohols in our laboratories, several improvements have been made to the catalytic system.5bc,6 These results are summarized in Table 1 for three different substrates.10 The original conditions, which employ toluene, can be accelerated by the addition of Cs2CO3 and t-butanol. The use of chloroform as a solvent permits reaction at a lower temperature, and facilitates the use of air as a reoxidant. Extensive studies of the substrate scope under these reaction conditions have been carried out, and the reaction has been employed in the synthesis of certain pharmaceutical intermediates.11 Despite these advancements, we were unable to find any ligand other than (−)-sparteine (1) capable of inducing high levels of selectivity in the reaction, and were thus limited to one enantiomeric series, as the other enantiomer of 1 is not readily available.12,13

Table 1.

Comparison of conditions for the kinetic resolution of secondary alcohols.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Originalb | Rate Acceleratedc | Chloroform O2d | Chloroform Aire | |

| O2, toluene 80 °C | O2, toluene, 60 °C Cs2CO3, t-BuOH | O2, CHCl3, 23 °C, Cs2CO3 | Air, CHCl3, 23 °C, Cs2CO3 | |

|

96 h | 9.5 h | 48 h | 24 h |

| 67% conv | 67% conv | 63% conv | 62% conv | |

| 98% ee | 99.5% ee | 99.9% ee | 99.8% ee | |

| s = 12 | s = 15 | s = 27 | s = 25 | |

|

40 h | 12 h | 24 h | 16 h |

| 69% conv | 62% conv | 58% conv | 60% conv | |

| 99.8% ee | 99% ee | 98% ee | 99.6% ee | |

| s = 16 | s = 21 | s = 28 | s = 28 | |

|

120 h | 12 h | 48 h | 44 h |

| 70% conv | 65% conv | 63% conv | 65% conv | |

| 92% ee | 88% ee | 98.7% ee | 98.9% ee | |

| s = 6.6 | s = 7.5 | s = 18 | s = 16 | |

nbd = norbornadiene, s = selectivity factor. 500 mg MS3Å/mmol substrate was used for all four sets of conditions.

5 mol% palladium catalyst, 0.20 equiv (−)-sparteine (1), 0.1 M in toluene.

5 mol% palladium catalyst, 0.20 equiv (−)-sparteine (1), 0.5 equiv Cs2CO3, 1.5 equiv t-BuOH, 0.25 M in toluene.

5 mol% palladium catalyst, 0.12 equiv (−)-sparteine (1), 0.40 equiv Cs2CO3, 0.25 M in CHCl3.

(sp)PdCl2 was used as catalyst (5 mol%). 0.07 equiv (−)-sparteine (1), 0.4 equiv Cs2CO3, 0.25 M in CHCl3. Reactions were run open to air through a short drying tube of Drierite.

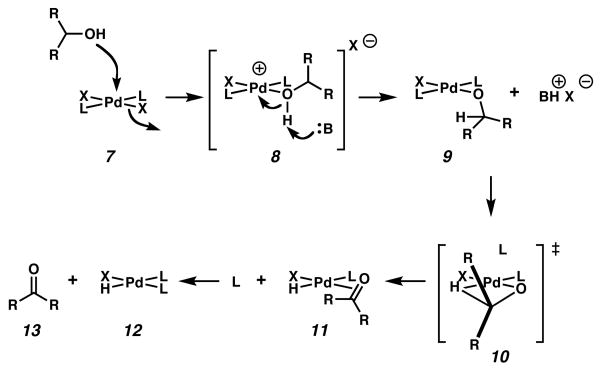

In general, the oxidation of alcohols to carbonyl compounds by palladium(II) most likely involves associative alcohol substitution at the palladium center (Figure 1, 7), deprotonation of the resulting palladium alcohol complex (8) by base to form a palladium alkoxide (9), and β-hydrogen elimination to the carbonyl compound (13, Figure 1, catalyst regeneration steps not shown).14 Sigman and coworkers have carried out extensive kinetic studies of the oxidative kinetic resolution using ((−)-sparteine)PdCl2 (14, (sp)PdCl2, Figure 2), (−)-sparteine (1), and O2. In their original publication, the authors report that β-hydrogen elimination is rate determining at high base concentration, and propose that the observed enantioselectivity results from a combination of the respective energy barriers for the elimination and the thermodynamic stabilities of the alkoxide complexes.6e A more recent publication from the same group has revised this original proposal, but maintains that β-hydrogen elimination from and reprotonation of the intermediate palladium alkoxide are the key kinetic influences on the selectivity.7 The alkoxide of the enantiomer that is oxidized undergoes β-hydrogen elimination more rapidly than the other, and is reprotonated more slowly.

Figure 1.

General mechanism of alcohol oxidation by palladium(II).

Figure 2a.

a The molecular structures are shown with 50% probability ellipsoids. The hydrogen atoms in the (−)-sparteine (1) backbone in the side view have been omitted for clarity.

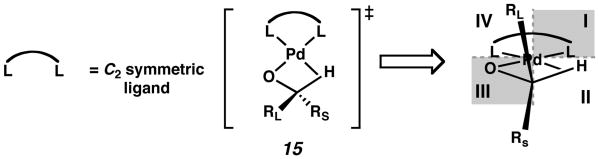

In the analysis described above, 1 was treated as a C2 symmetric ligand.15 Only two diastereomeric palladium alkoxides are considered, while in fact four diastereomers are possible because (−)-sparteine is C1 symmetric. Since the introduction of the DIOP ligand by Kagan in 1972,16C2 symmetry has been a dominant guiding force in the design of improved ligands for enantioselective transition-metal catalyzed reactions. In this respect, a C2 symmetric scaffold offers distinct advantages: the presence of a symmetry axis reduces the number of competing diastereomeric reaction pathways, enables a more straightforward analysis of substrate-catalyst interactions, and simplifies mechanistic and structural studies.17 The chiral scaffold of a C2 symmetric ligand can be modeled by a quadrant diagram of the ligand–metal complex, in which quadrants I and III (or II and IV) are equivalently hindered (Figure 2A). (sp)PdCl2 (14) can be mapped onto this quadrant representation, but the hemispheres of this complex are clearly nonequivalent. 18 As can be seen from the solid-state structure, Cl1 and Cl2 are located in different steric environments, due to the different influence of each of the flanking piperidine rings of (−)-sparteine (1). Thus, it is perhaps more accurate to depict 14 with quadrant I fully blocked, but quadrant III only partially blocked (Figure 2B).

Given that β-hydrogen elimination is key to enantiodifferentiation, it was also not obvious to us how a C2 symmetric ligand could induce asymmetry in this process. Figure 3 depicts the transition state for β-hydrogen elimination (see below) imposed on a quadrant diagram for a C2 symmetric ligand. As the β-agostic interaction between the palladium center and the C–H atom approaches a full Pd–H bond, the transition state becomes more and more symmetrical. If the secondary carbon atom is aligned with the origin point of the quadrant diagram, in fact RL and RS are in identical steric environments.

Figure 3.

To understand why (−)-sparteine (1) was the only highly effective ligand for the oxidative kinetic resolution, we became interested in exploring the steric environment that 1 created in palladium complexes. We chose to address the extent to which the C1 symmetric (−)-sparteine (1) mimics C2 symmetry when bound to PdCl2. Reported herein are the full results of these investigations, which culminated in an experimentally derived model for the selectivity observed in the oxidative kinetic resolution of secondary alcohols. Further studies involving two other members of the lupin alkaloid family, (−)-α- and (+)-β-isosparteine,19 complement our model and belie the superiority of C2 symmetric ligands for all enantioselective reactions. We show also the significance of the halide ligand in enantioinduction, which is also borne out by calculations.

Results and Discussion

Reactivity of (sp)PdCl2 (14) with pyridine derivatives and their solid-state structures

To experimentally test the degree to which the C1 symmetric ligand (−)-sparteine (1) approaches C2 symmetry, a series of substitution reactions were carried out on (sp)PdCl2 (14). In an initial experiment, 14 was treated with 1 equiv of AgSbF6 in the presence of pyridine (Scheme 2) at 25 °C in CH2Cl2 to provide 91% yield of a crystalline product. We anticipated that if 1 behaved as a C2 symmetric ligand, two cationic pyridyl complexes (16 and 17) would form in nearly equivalent amounts. In the event, one major species was observed by 1H and 13C NMR in acetone-d6 along with a small amount of another compound. The analysis of a single crystal of the product by X-ray diffraction revealed complex 16. 20 This was our first indication that (−)-sparteine (1) does not mimic C2 symmetry.

Scheme 2a.

a The molecular structures are shown with 50% probability ellipsoids. The hydrogen atoms in the ligand backbone in the side view and the SbF6− ion in both views have been omitted for clarity.

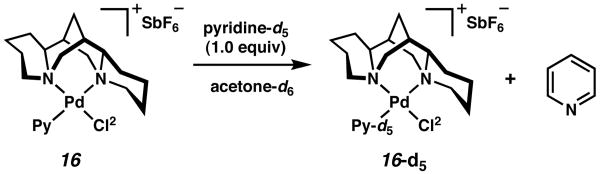

Although a solution state structural analysis was not carried out, the major component in solution appears to be 16. Treatment of the complex with pyridine-d5 in acetone showed rapid deuterium incorporation and liberation of free pyridine at 25 °C (Scheme 3). It is unclear at this time what accounts for the minor component observed in solution. Observation of 16 by 1H NMR at 15 degree intervals from −60 °C to 45 °C in acetone-d6 showed almost no change in the product ratio.

Scheme 3.

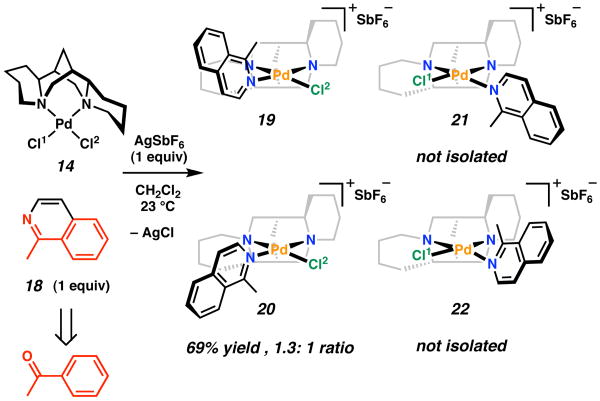

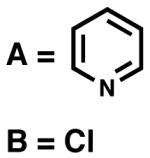

We next investigated the reaction of 14 with a bulkier pyridine-related compound, 2-methyl isoquinoline (18). The structure and geometry of 18 can be considered structurally analogous to acetophenone, the product of the kinetic resolution (Scheme 4). Under the same reaction conditions, (sp)PdCl2 (14) reacts with AgSbF6 in the presence of 18 to produce a crystalline product in moderate yield. If (−)-sparteine (1) were exhibiting the properties of a C2 symmetric ligand, we anticipated that four possible diastereomeric products could form, resulting from substitution at either Cl1 or Cl2 and the atropisomer at each position, but that two would dominate: 19 and 21, or 20 and 22. In the event, two major compounds are indeed observed by 1H NMR in a 1.3:1 ratio in acetone-d6 at 25 °C. However, analysis in the solid state by X-ray crystallography revealed only substitution of Cl1, with both orientations of the isoquinoline ligand related by a rotation of 180° around the Pd-N bond occupying the site, i.e., 19 and 20 (for crystallographic structures, see Supporting Information).21 This outcome provided further evidence against the possibility that 1 behaved with pseudo C2 symmetry in this complex. In addition, the mixture of products indicated that the (sp)PdCl2 fragment was not able to completely discriminate the prochiral faces of a planar molecule, albeit one with a steric environment similar to that of acetophenone.

Scheme 4.

In order to probe the steric environment of the (sp)PdCl2 fragment further, we turned to an even bulkier ligand, 2-mesityl pyridine (23). In this instance, under identical conditions to the syntheses of 16 and 19/20, we observed a good yield of one major product out of four possible by 1H NMR in acetone-d6 with approximately 5% of a minor component (Scheme 5). The presence of a single major product indicated that not only had substitution occurred at a single site of the palladium center, but that a single atropisomer about the Pd–N bond was favored, for a suitably bulky ligand. X-ray crystallographic analysis showed that Cl1 had been substituted as in 16 and 19/20 to give 24, and that the mesityl group resided exclusively in quadrant IV.

Scheme 5.

a The molecular structures are shown with 50% probability ellipsoids. The hydrogen atoms in the ligand backbone in the side view and the SbF6− ion in both views have been omitted for clarity.

The ratio of major and minor products observed in the 1H NMR spectrum remained nearly unchanged from −60 °C to 45 °C in acetone-d6 (see Supporting Information). The addition of an equivalent of 2-mesitylpyridine (23) resulted in an increase in the minor peaks in the aryl region of the spectrum, and a disappearance of the minor peaks in the region from 1 to 5 ppm corresponding to palladium-bound (−)-sparteine (1). Thus, the minor product observed by NMR is likely dissociated ligand and an acetone•(sp)PdCl cation, and not any of the other possible positional or rotational isomers.

These ligand substitution experiments present convincing evidence that (−)-sparteine (1) does not mimic a C2 symmetric ligand when bound to PdCl2, and provide information about the steric environment this ligand creates. The unique architecture favors substitution at site A on the palladium center, as depicted in Figure 4, and can sterically distinguish quadrants III and IV for sufficiently bulky unsymmetrical ligands. Most importantly, quadrants I and III are differentiated, unlike in a truly C2 symmetric ligand.

Figure 4.

The synthesis and reactivity of palladium alkoxides relevant to the oxidative kinetic resolution

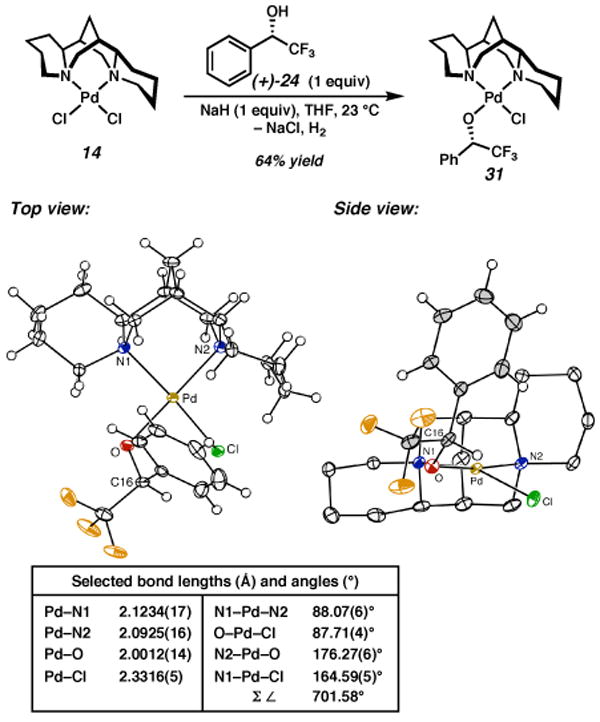

To better understand the enantioselective oxidation itself, we set out to synthesize an alkoxide complex relevant to our system. While numerous palladium alkoxides have been characterized, few bear β-hydrogen atoms due to the ease of β-hydrogen elimination.22 A meaningful steric model for the prototypical oxidative kinetic resolution substrate 1-phenylethanol (28) is α-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl alcohol 29 (Figure 5).23 Under our kinetic resolution conditions, 29 does not react, presumably because the electron-withdrawing trifluoromethyl group disfavors the β-agostic interaction between the palladium atom and the benzylic C–H bond that precedes elimination. Thus, we hoped that a palladium-alkoxide complex of this alcohol would be relatively stable, and serve as a model of a relevant intermediate in the oxidation reaction. In this way such an alcohol would act as a “suicide inhibitor,” or as a sort of trap for a reactive intermediate. Alcohol (+)-29, which corresponds to the more reactive enantiomer of 1-phenylethanol ((+)-28) in the resolution chemistry, was chosen as an initial target for palladium-alkoxide formation.

Figure 5.

Treatment of complex 14 with the sodium alkoxide of (+)-29 produced a 64% yield of recrystallized material that was a single major product as observed by 1H NMR in CD2Cl2 (Scheme 6). The product was shown to be alkoxide complex 31 by X-ray analysis. A single atropisomer is observed and again substitution of Cl1 occurs exclusively. The phenyl moiety is located in quadrant IV in an orientation similar to that of the mesityl group of complex 24. As for the cationic pyridyl complexes described above (i.e., 24), the square plane of 31 is distorted such that Cl2 is displaced toward open quadrant II. In addition, the benzylic C–H bond is oriented toward the palladium center, and parallel to the distorted Pd–Cl bond.

Scheme 6.

a The molecular structures are shown with 50% probability ellipsoids. The hydrogen atoms in the ligand backbone in the side view have been omitted for clarity.

Thermolysis of 31 in toluene-d8 led to little, if any, ketone. However, when 31 was treated with 1.5 equiv of AgSbF6 in CD2Cl2 at 25 °C, immediate production of ketone 32 in 92% yield was observed along with unidentified palladium decomposition products (Scheme 7).24 Silver cation appears to act as a trigger that releases the “trapped” intermediate to undergo β-hydrogen elimination.

Scheme 7.

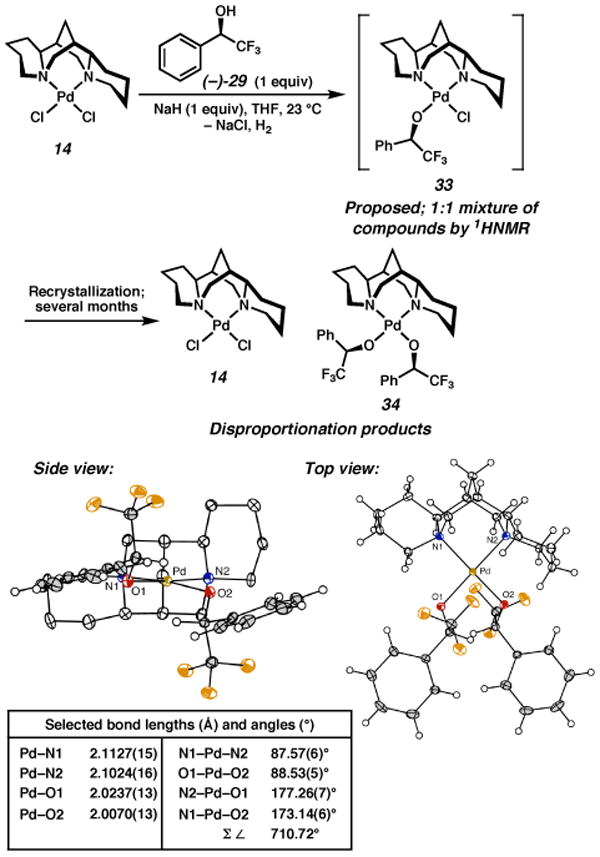

The synthesis of the other diastereomer of palladium alkoxide, arising from the opposite enantiomer of alcohol ((−)-29), was also pursued. When (−)-29 was treated with sodium hydride and added to 14, however, two major products were observed by 1H NMR in an approximately 1:1 ratio (Scheme 8). This was our initial indication that the interaction between the (sp)PdCl fragment and the alcohol corresponding to the slow-reacting enantiomer of 1-phenylethanol ((−)-29) was more complicated than that for (+)-29. The products did not crystallize readily, and only after standing for a period of several months at −18 °C was a mixture of orange and yellow crystals obtained. X-ray analysis revealed the yellow crystals to be bisalkoxide 34, the 1H NMR spectrum of which was not present in the spectrum of the original product mixture. The orange crystals were dichloride complex 14, also not observed in the original 1H NMR spectrum. We propose that the initially formed products are a mixture of alkoxide atropisomers that cannot undergo β-hydrogen elimination, and which eventually disproportionate to 14 and 34.

Scheme 8a.

a The molecular structures are shown with 50% probability ellipsoids. The hydrogen atoms in the ligand backbone in the side view have been omitted for clarity.

It is unclear why alcohol (−)-29 forms a more complex initial product mixture than the other enantiomer, or why disproportionation occurs. On the basis of the solid state structure of the bisalkoxide, one possibility is that the aryl group, now oriented toward quadrant III, experiences a steric clash with Cl2, which destabilizes the complex and leads to disproportionation.25 Such an interaction could also lead to rotation around the Pd–O bond, giving rise to the mixture of products initially observed. In the bisalkoxide complex, the N1–Pd–O2 angle is less acute than the corresponding N1-Pd-Cl angle in monoalkoxide complex 31 (173.14° vs 164.59°), a geometry which perhaps can better accommodate a bulkier group in quadrant III.

Experimentally derived model for the stereoselectivity observed in the oxidative kinetic resolution of secondary alcohols

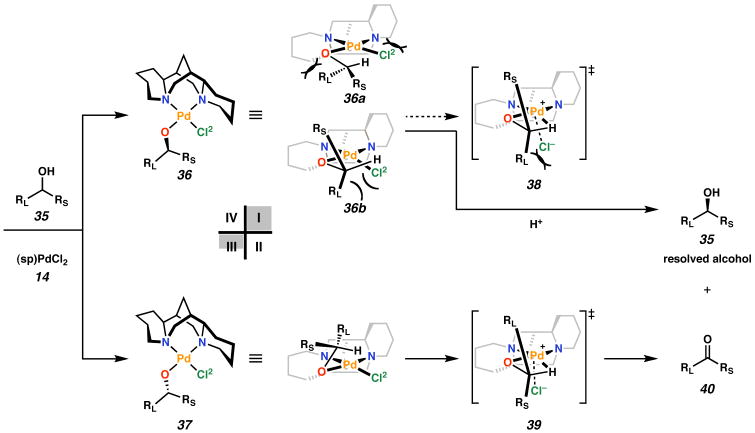

On the basis of the reactivity of (sp)PdCl2 (14) and the structures of 16, 19/20, 24, 31, and 34, we have proposed a general model for asymmetric induction in the palladium-catalyzed oxidative kinetic resolution of secondary alcohols.26 Upon reaction of complex 14 with a racemic mixture of alcohol (35), Cl1 is substituted preferentially over Cl2 to form two diastereomeric palladium alkoxides (Figure 6, 36 and 37). Either could be reprotonated leading to alcohol dissociation, or could undergo β-hydrogen elimination to afford ketone. Given the geometry of the solid state structure of palladium-alkoxide complex 31, we propose that for the reactive diastereomer (37), the unsaturated moiety (RL) is located in open quadrant IV. In this geometry, the secondary C–H bond is positioned opposite the oblique Pd–Cl bond. The same orientation of RL in quadrant IV of the less reactive diastereomer 36 requires that the C–H bond point away from Pd (not shown). Alternatively, for diastereomer 36, the C–H bond could approach from the opposite face of the square plane, as depicted by 36a. This geometry, however, would be expected to induce destabilizing interactions between the alkoxide moiety and the piperidine ring in quadrant III, and between the chloride ligand and the piperidine ring in quadrant I. On the basis of the solid state structure of bisalkoxide 34, we expect that unreactive diastereomer 36 likely has the geometry shown in 36b.

Figure 6.

Model for the enantioselction in the oxidative kinetic resolution by (sp)PdCl2.

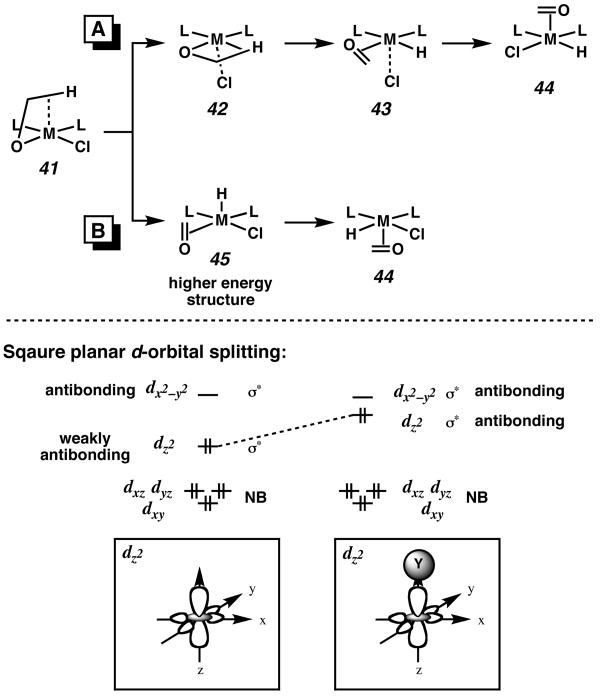

The transition state for β-hydrogen elimination (i.e., 38 or 39) is expected to involve a developing cationic palladium species with 4-coordinate square planar geometry,27 although calculations for this system have shown that Cl− remains closely associated below the square plane (see below). A schematic representation of β-hydrogen elimination for our ligand set is shown in Figure 7. The C–H bond likely moves into the square plane by an associative substitution mechanism and displacement of the chloride ligand (41). β-Hydrogen elimination results in an intermediate possessing a hydride in a basal position (43). It is possible that β-hydrogen elimination could occur directly from an apical position (Figure 5B). In this case, elimination would result in an apical hydride ligand (45). However, because the weakly antibonding dz2 orbital of a square planar d8 complex is already filled, the introduction of a σ-bonding apical ligand creates a fully antibonding interaction. Because hydride is a stronger σ-donor than chloride, apical β-hydrogen elimination would result in a higher-energy intermediate (45) than if chloride is forced into the apical position (42). In examples of β-hydrogen elimination from alkyl complexes, the hydride is delivered to a vacant orbital, and not a filled one. Furthermore, calculations by Hoffmann have shown that for five-coordinate, square pyramidal species, hydride ligands prefer to be basal.28

Figure 7.

β-Hydrogen elimination from a square planar d8 complex.

In structure 31, and in 37 by analogy, the reactive C–H bond is poised to achieve the conformation for β-hydrogen elimination via 39 after displacement of Cl2 into quadrant II (Figure 6). This sequence of events minimizes potential steric interactions en route to ketone. In contrast, achievement of a similar conformation by diastereomer 36 would entail a destabilizing interaction between RL and quadrant III or between Cl2 and quadrant I. Furthermore, and perhaps more importantly, a closely associated chloride ion in the apical position below the square plane could further disfavor the diastereomeric transition state (38) by steric crowding with RL. Thus, 37 reacts to form ketone (40), while 36 protolytically dissociates to the observed enantiomer of resolved alcohol (35). This model predicts the absolute stereochemical outcome of every (sp)PdCl2 (14) catalyzed oxidative kinetic resolution performed to date.

Extensive calculations by Goddard and coworkers on the oxidative kinetic resolution catalyzed by (sp)PdCl2 (14) provide theoretical support to the model described herein.9 The high-level calculations determine the geometry of the alkoxide intermediate for sec-phenethyl alcohol to be similar to that found in the solid-state structure of 31, our model compound for this intermediate. β-Hydrogen elimination proceeds by displacement of the chloride anion by the benzylic C–H bond, although the chloride ion, while not fully bound, remains closely associated to the metal center in the transition state. Significantly, when the chloride ligand was left out of the calculation of the barriers to β-hydrogen elimination from each diastereomer, little difference was found, which indicates that the rates would be similar. Thus, the chloride anion appears to be essential to the selectivity.

Effect of the halide ligand on selectivity and reactivity

On the basis of the experiments and calculations described above, chloride anion appears to play an essential role in communicating the chirality of (−)-sparteine (1) to the bound substrate. Table 2 compares the angles around the square plane determined from the solid-state structures for the (sp)Pd-derived complexes reported herein. The largest disparity among the complexes is in the N1–Pd–B, A–Pd–B and N1–Pd–A angles. The 2-mesityl pyridine cationic complex (24) and the monoalkoxide (31) are the most distorted, the sum of the six angles between ligands being 699.45° and 701.58°, respectively, compared to 720° in a perfect square plane and 657° for a tetrahedral geometry. Because, as proposed, Cl2 remains close to the palladium atom throughout the reaction, it may effectively block quadrant II leaving only one quadrant open for substrate binding. In this way, the transition state for β-hydrogen elimination is further desymmetrized (see Figure 3).

Table 2.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 14 | 16 | 19/20 | 24 | 31 | 34 | |

| N1–Pd–B | 170.06° | 168.52° | 167.22° | 163.51° | 164.59° | 173.14° |

|

| ||||||

| N2–Pd–A | 176.24° | 176.64° | 175.35° | 175.42° | 176.27° | 177.26° |

|

| ||||||

| A–Pd–B | 83.09° | 81.52° | 80.21° | 82.53° | 87.71° | 88.53° |

|

| ||||||

| N1–Pd–N2 | 87.51° | 87.39° | 87.58° | 87.48° | 88.07° | 87.57° |

|

| ||||||

| N1–Pd–A | 95.65° | 95.73° | 96.85° | 96.95° | 89.78° | 92.65° |

|

| ||||||

| N2–Pd–B | 93.44° | 95.67° | 95.16° | 93.56° | 95.16° | 91.57° |

|

| ||||||

| Σ ∠ | 705.99° | 705.47° | 702.37° | 699.45° | 701.58° | 710.72° |

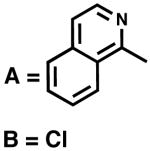

If this proposed role for chloride is correct, then a larger, but still coordinating ligand at position B should improve the kinetic resolution. To investigate this possibility, (sp)PdBr2 (45) was pursued. Ligation of 22 to palladium precursor 46 occurred in moderate yield to provide 45 (Scheme 9). The molecular structure of 45 obtained by X-ray diffraction of a single crystal shows that the Pd–Br2 bond is further distorted than the Pd–Cl2 bond of 14. The sum of the angles between the six ligands is 699.22°, which is comparable to the most tetrahedrally distorted complex containing a chloride at position B (24, Table 2).

Scheme 9a.

a The molecular structures are shown with 50% probability ellipsoids. The hydrogen atoms in the ligand backbone in the side view have been omitted for clarity.

45 was tested in the kinetic resolution reaction of 1-phenylethanol (28). The results for two sets of conditions are shown in Table 3 (entries 1 and 2).10 Interestingly, high selectivites are obtained at rates 3 to 7 times faster than with (sp)PdCl2 (14, entries 3 and 4). The effect of the bromide ligand appears to be rate acceleration with comparable selectivity.

Table 3.

Kinetic resolution with (sp)PdBr2 (45).

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | X | Conditions | time | % conversion | %ee | s |

| 1 | Br | A | 28 h | 62 | 99 | 28 |

| 2 | Br | B | 6.5 h | 56 | 94 | 22 |

| 3 | Cl | A | 96 h | 60 | 98 | 23 |

| 4 | Cl | B | 48 h | 60 | 99 | 31 |

The properties and reactivity of α-isosparteine and β-isosparteine in the oxidative kinetic resolution

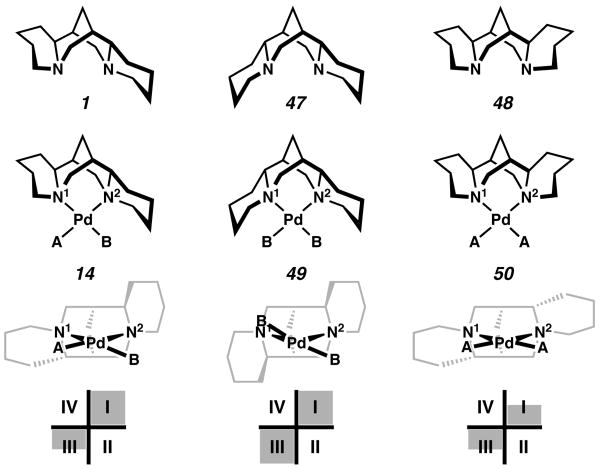

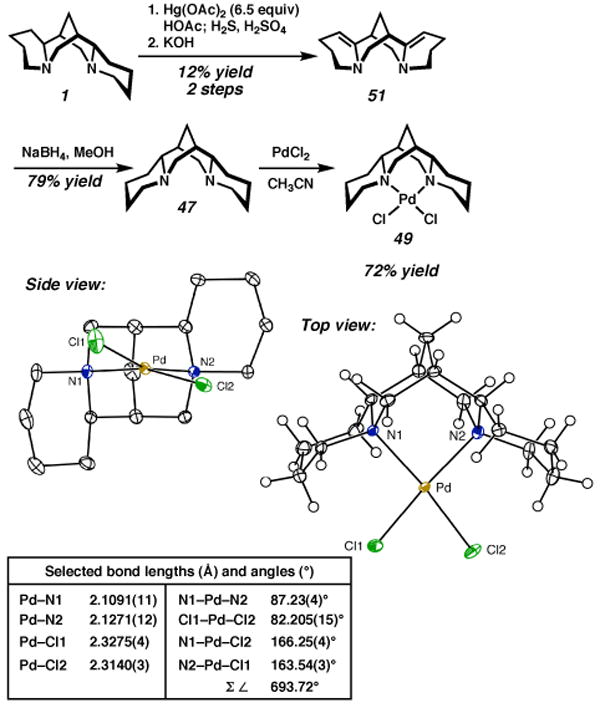

Having developed a model for selectivity, our attention again turned to the issue of symmetry and whether the C2 symmetric diastereomers of (−)-sparteine (1) would be more or less selective in the kinetic resolution. The PdCl2 complexes of the three diastereomers are shown in Figure 8 for comparison.29,30 For (−)-sparteine (1), the reactions of 14 we have thus far observed have occurred primarily at site A, which appears to be the relevant site of substitution in the kinetic resolution. For the (−)-α-isosparteine (47) complex ((α-isosp)PdCl2, 49), reaction, if any, would be forced to occur at a B site, by analogy to 1. That is, both anionic ligands of 49 would be in an environment identical to that of Cl2 in (sp)PdCl2 (14). On the other hand, for the (+)-β-isosparteine (48) complex ((β-isosp)PdCl2, 50), in which both flanking piperidine rings are directed away from the metal center, only A sites are available. It was unclear to us what effect this would have on the rate of oxidation. If the C1 symmetry of (−)-sparteine (1) is essential to its unique selectivity in the kinetic resolution, a comparison of the three diastereomers would reveal this point.

Figure 8.

Sparteine and isosparteine diastereomers and their complexes with PdCl2.

(−)-α-Isosparteine (47) was prepared by the method of Leonard (Scheme 10).31 Dehydrogenation with mercuric acetate and diastereoselective reduction of the resulting bisenamine 51 provides (−)-α-isosparteine (47). The ligand was reacted with palladium dichloride to give (α-isosp)PdCl2 (49), and a solid state structure was obtained by X-ray crystallography. In this structure, both Pd–Cl bonds are deflected from planarity by the flanking piperidine rings of the sparteine ligand, and the sum of the six angles around the square plane is 693.72°, the smallest for our sparteine complexes thus far.

Scheme 10a.

a The molecular structures are shown with 50% probability ellipsoids. The hydrogen atoms in the ligand backbone in the side view have been omitted for clarity.

(+)-β-Isosparteine (48) was prepared by the method of Winterfeld.32 Thermolysis of (−)-sparteine (1) in the presence of 1.17 equiv of AlCl3 at 180-200° in a sealed tube provided a mixture of all three sparteine diastereomers (Scheme 11). Separation by column chromatography provided 48.33 Ligation to palladium dichloride was achieved in CH2Cl2, and a solid-state structure of (β-isosp)PdCl2 (50) was obtained by X-ray crystallography. Without the steric intrusion of the trans quinolizidine ring system at the metal center, the complex is more planar. The sum of the angles around the palladium atom is 710.68°, comparable to bisalkoxide 34, and the closest to square planar geometry of any sparteine-derived complexes containing a chloride ligand.

Scheme 11.

a The molecular structures are shown with 50% probability ellipsoids. The hydrogen atoms in the ligand backbone in the side view have been omitted for clarity.

The oxidative kinetic resolution of 1-phenylethanol (28), our prototypical substrate, was attempted under our standard conditions with 5 mol% of the catalyst (49 or 50) and 0.15 equiv of excess (−)-α- or (+)-β-isosparteine (47 or 48) in toluene at 80 °C in the presence of O2 and MS3Å (Table 4). After 72 h, with the (−)-α-isosparteine system, 34% conversion with 29% ee was obtained, for a selectivity factor (s) of 4.7 compared to s = 17.3 with (sp)PdCl2 (14, entries 1 and 2). (−)-α-Isosparteine (47) appears to induce a much lower reactivity and selectivity in the kinetic resolution. To account for any effect that free ligand may have on the selectivity, the kinetic resolution was carried out in the absence of excess ligand, but with cesium carbonate as a stoichiometric base (entries 3 and 4).34 The reaction with 49 as catalyst showed little conversion and almost no selectivity.35 For the (+)-β-isosparteine (48) system, whether with excess ligand (entry 5) or inorganic base (entry 6), there is essentially no selectivity.

Table 4.

Oxidative kinetic resolution with (−)-α-iso- and (+)-β-isosparteine.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | catalyst | base | time | % conv. | %ee | s |

| 1a | (α-isosp)PdCl2(49) | 47b | 72 h | 34 | 29 | 4.7 |

| 2c | (sp)PdCl2(14) | 1b | 24 h | 58 | 93 | 17.3 |

| 3a | (α-isosp)PdCl2(49) | Cs2CO3d | 12 h | 17 | 5 | 2 |

| 4a | (sp)PdCl2(14) | Cs2CO3d | 12 h | 36 | 35 | 6.0 |

| 5a | (β-isosp)PdCl2(50) | 48b | 17 h | 31 | 4 | 1 |

| 6 | (β-isosp)PdCl2(50) | Cs2CO3d | 17 h | 45 | 6 | 1 |

Average of two runs.

0.15 equiv ligand.

Average of three runs.

1.0 equiv Cs2CO3.

The poor selectivity and low reactivity of (α-isosp)PdCl2 (49) in the kinetic resolution support our hypothesis that (−)-sparteine (1) is a particularly effective ligand due to its C1 symmetry. While the increased steric bulk that (−)-α-isosparteine (47) provides close to the metal center could be expected to increase the steric interactions that control selectivity, it instead hampers even reactivity. In addition, no benefit is gained from the increased symmetry of the ligand, which stands in contrast to many asymmetric reactions for which a C2 symmetric ligand provides better selectivity.17 These results also provide further indication that site A of the (sp)Pd fragment (Figure 6) is the relevant reactive site, and that a Curtin-Hammett situation seems unlikely to be operative in the reaction.

(α-isosp)PdCl2 (49) is likely a less-reactive catalyst because approach of the substrate and formation of the postulated palladium alkoxide intermediate is hindered by the additional steric bulk; reaction at site B of (sp)PdCl2 (14) was never favored in the formation of cationic pyridine complexes. On the other hand, because (β-isosp)PdCl2 (50) features two type A sites, it likely forms an alkoxide complex, but this is slower to undergo β-hydrogen elimination. This may be the case if a distorted Pd–Cl2 bond is necessary for good reactivity; such distortion may facilitate displacement of Cl2 to an axial position below the square plane by a C–H agostic interaction (Figure 5). Another possibility is that the more exposed palladium center can easily form a stable bisalkoxide that is resistant to β-hydrogen elimination.

These results provide strong evidence that the truly C2 symmetric diastereomers of (−)-sparteine (1) are inferior ligands for the oxidative kinetic resolution in terms of both selectivity and reactivity. (−)-Sparteine (1) is perhaps especially effective for this reaction because it provides a highly specific steric environment at the palladium center. One coordination site is accessible to the substrate (site A, or quadrant IV), whereas the others contain the steric bulk necessary to desymmetrize the transition state enough to effect selectivity (Cl at site B, quadrants I and II). Unlike many catalytic enantioselective processes in which the chiral ligand blocks one face of a prochiral substrate from reaction, the oxidative kinetic resolution reaction creates a prochiral molecule. This unusual scenario seems to require a ligand environment more exotic than that provided by standard C2 symmetric ligands.36

Summary and Conclusion

We have developed a model for the stereoselectivity in the Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidative kinetic resolution of secondary alcohols. The model is based on the solid-state structures of coordination complexes and general reactivity trends of (sp)PdCl2 (14). The first solid state structure of a non-racemic chiral palladium alkoxide is presented and further demonstrates the subtle steric influences of the ligand (−)-sparteine (1). High-level calculations support our model and emphasize the essential role that the halide ligand plays in selectivity. The C2 symmetric diasteromers of (−)-sparteine (1), (−)-α-isosparteine (47) and (+)-β-isosparteine (48), were synthesized and investigated from a structural standpoint as well as in the oxidation reaction itself. Both were less selective and less reactive than (−)-sparteine (1), which supports the unusual conclusion that a C1 symmetric ligand is particulary effective for this oxidative kinetic resolution.

Supplementary Material

Experimental details, x-ray data, enlarged schemes from the text, and NMR spectra are available free of charge.

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to our late friend and colleague Professor Nelson J. Leonard, 1916-2006. The authors wish to thank the NIH-NIGMS (R01 GM65961-01), Bristol-Myers Squibb Company and the American Chemical Society (graduate fellowship to R.M.T.), Merck Research Laboratories, Abbott Laboratories, Pfizer, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, and Johnson and Johnson for generous financial support. Mr. Lawrence Henling and Dr. Michael Day are gratefully acknowledged for X-ray crystallographic structural determination.

References

- 1.Mohr JT, Ebner DC, Stoltz BM. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:3571–3576. doi: 10.1039/b711159m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wieland H. Ber. 1912;45:484–493. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz J, Blackburn TF. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1977:157–158. [Google Scholar]

- 4.For recent Pd(II) aerobic alcohol oxidations, see: Peterson KP, Larock RC. J Org Chem. 1998;63:3185–3189.Nishimura T, Onoue T, Ohe K, Uemura S. J Org Chem. 1999;64:6750–6755. doi: 10.1021/jo9906734.Brink GJ, Arends IWCE, Sheldon RA. Science. 2000;287:1636–1639. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1636.For a review, see: Muzart J. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:5789–5816.

- 5.(a) Ferreira EM, Stoltz BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7725–7726. doi: 10.1021/ja015791z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bagdanoff JT, Ferreira EM, Stoltz BM. Org Lett. 2003;5:835–837. doi: 10.1021/ol027463p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For conditions employing chloroform and air, see: Bagdanoff JT, Stoltz BM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:353–357. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352444.

- 6.For a similar system, see: Jensen DR, Pugsley JS, Sigman MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7475–7476. doi: 10.1021/ja015827n.Mueller JA, Jensen DR, Sigman MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:8202–8203. doi: 10.1021/ja026553m.Jensen DR, Sigman MS. Org Lett. 2003;5:63–65. doi: 10.1021/ol027190y.Mandal SK, Jensen DR, Pugsley JS, Sigman MS. J Org Chem. 2003;68:4600–4603. doi: 10.1021/jo0269161.Mueller JA, Sigman MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:7005–7013. doi: 10.1021/ja034262n.Mandal SK, Sigman MS. J Org Chem. 2003;68:7535–7537. doi: 10.1021/jo034717r.

- 7.Mueller JA, Cowell A, Chandler BD, Sigman MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14817–14824. doi: 10.1021/ja053195p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trend RM, Stoltz BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4482–4483. doi: 10.1021/ja039551q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen RJ, Keith JM, Stoltz BM, Goddard WA. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7967–7974. doi: 10.1021/ja031911m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The selectivity factor, s, or krel was determined by the following equation: s = krel = ln[(1-C)(1 − ee)]/ln[(1 − C)(1 + ee)] where C is conversion and ee is enantiomeric excess.

- 11.Caspi DD, Ebner DC, Bagdanoff JT, Stoltz BM. Adv Synth Catal. 2004;346:185–189. [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Brien and coworkers have synthesized analogues of (+)-sparteine that are somewhat effective as sparteine surrogates, see: Dearden MJ, Firkin CR, Hermet JPR, O'Brien P. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:11870–11871. doi: 10.1021/ja027774v.Hermet JPR, Porter DW, Dearden MJ, Harrison JR, Koplin T, O'Brien P, Parmene J, Tyurin V, Whitwood AC, Gilday J, Smith NM. Org Biomol Chem. 2003;1:3977–3988. doi: 10.1039/b308410h.Dearden MJ, McGrath MJ, O'Brien P. J Org Chem. 2004;69:5789–5792. doi: 10.1021/jo049182w.Ebner DC, Trend RM, Genet C, McGrath MJ, O'Brien P, Stoltz BM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:6367–6370. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801865.

- 13.The use of a binaphthyl-derived N-heterocylic carbene ligand with PdI2 has recently been reported, with moderate levels of selectivity: Chen T, Jiang JJ, Xu Q, Shi M. Org Lett. 2007;9:865–868. doi: 10.1021/ol063061w.

- 14.(a) Sheldon RA, Arends IWCE. In: Advances in Catalytic Activation of Dioxygen by Metal Complexes. Simándi LI, editor. Vol. 26. Kluwer; Dordrecht: 2003. p. 123. Ch 3. [Google Scholar]; (b) Steinhoff BA, Stahl SS. Org Lett. 2002;4:4179–4181. doi: 10.1021/ol026988e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Stahl SS, Thorman JL, Nelson RC, Kozee MA. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7188–7189. doi: 10.1021/ja015683c. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.For another example that uses similar logic for (−)-sparteine, see: Li X, Schenkel LB, Kozlowski MC. Org Lett. 2000;2:875–878. doi: 10.1021/ol9903133.

- 16.Kagan HB, Dang TP. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:6429–6433. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitesell JK. Chem Rev. 1989;89:1581–1590. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Structure originally reported in ref. 4a.

- 19.Leonard NJ. In: The Alkaloids, Chemistry and Physiology. Manske RHF, Holmes HL, editors. III. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1953. pp. 119–199. [Google Scholar]

-

20.The same product was observed in the reaction of the chloro-bridged dimer with 2.0 equiv of pyridine in 91% yield.

- 21.Two molecules were found in the asymmetric unit. See Supporting Information for further details.

- 22.For examples that possess β-hydrogen atoms, see: Bouquillon S, du Moullinet d'Hardemare A, Averbuch-Pouchot MT, Henin F, Muzart J, Durif M. Acta Crystallogr Sect C: Cryst Struct Commun. 1999;55:2028–2030.Achternbosch M, Klufers P. Acta Crystallogr Sect C: Cryst Struct Commun. 1994;50:175–178.Hubel R, Polborn K, Beck W. Eur J Inorg Chem. 1999:471–482.Kapteijn GM, Grove DM, van Koten G, Smeets WJJ, Spek AL. Inorg Chim Acta. 1993;207:131–134.Klufers P, Kunte T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:4210–4212. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011119)40:22<4210::AID-ANIE4210>3.0.CO;2-Z.Kastele X, Klufers P, Kunte TZ. Anorg Allg Chem. 2001;627:2042–2044.Kapteijn GM, Baesjou P, Alsters PL, Grove DM, Smeets WJJ, Kooijman H, Spek AL, van Koten G. Chem Ber. 1997;130:35–44.Kapteijn GM, Dervisi A, Grove DM, Kooijman H, Lakin MT, Spek AL, van Koten G. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:10939–10949.Ahlrichs R, Ballauff M, Eichkorn K, Hanemann O, Kettenbach G, Klufers P. Chem Eur J. 1998;4:835–844.Klufers P, Kunte T. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2002:1285–1289.

- 23.A racemic Pd(II) alkoxide complex of (±)-29 has been reported: [(PMe3)2Pd(Me)(OR)] where R = PhCH(CF3). See: Kim YJ, Osakada K, Takenaka A, Yamamoto A. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:1096–1104.

- 24.Yield was determined by 1H NMR using an internal standard, see Supporting Information.

- 25.Another possibility is that the thermodynamics of solubility play a role.

- 26.While the structural studies we have undertaken have been almost exclusively in the solid state, the consistency of the results and the support of theoretical calculations give us confidence in our model.

- 27.(a) Bryndza HE, Tam W. Chem Rev. 1988;88:1163–1188. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhao J, Hesslink H, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7220–7227. doi: 10.1021/ja010417k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For an alternative with platinum see: Bryndza HE, Calabrese JC, Marsi M, Roe DC, Tam W, Bercaw JE. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:4805–4813.

- 28.Thorn DL, Hoffmann R. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:2079–2090. [Google Scholar]

- 29.For references pertaining to α-isosparteine, see: Winterfeld K. Arch Pharm. 1928;266:299–325.Marion L, Turcotte F, Ouellet J. Can J Chem. 1951;29:22–29.Galinovsky F, Knoth P, Fischer W. Monatsh Chemie. 1955;86:1014–1023.Leonard NJ, Thomas PD, Gash VW. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:1552–1558.Oinuma H, Dan S, Kakisawa H. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1983:654–655.Blakemore PR, Kilner C, Norcross NR, Astles PC. Org Lett. 2005;7:4721–4724. doi: 10.1021/ol0519184.Przybylska M, Barnes WH. Acta Cryst. 1953;6:377–384.

- 30.For references pertaining to β-isosparteine, see: Greenhalgh R, Marion L. Can J Chem. 1956;34:456–458.Carmack M, Douglas B, Martin EW, Suss H. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:4435.Carmack M, Goldberg SI, Martin EW. J Org Chem. 1967;32:3045–3049. doi: 10.1021/jo01285a024.Wanner MJ, Koomen GJ. J Org Chem. 1996;61:5581–5586.Childers LS, Folting K, Merritt LL, Jr, Streib WE. Acta Cryst. 1975;B31:924–925.

- 31.Leonard NJ, Beyler RE. J Am Chem Soc. 1950;72:1316–1323. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winterfeld K, Bange H, Lalvani KS. Justus Liebigs Ann Chem. 1966;698:230–234. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Although the sign of rotation is different than for (−)-sparteine (1) and (−)-α-isosparteine (47), it is in the same enantiomeric series.

- 34.Cesium carbonate (along with excess (−)-spartieine) is a component of the “rate-accelerated” conditions for oxidative kinetic resolution.

- 35.While the selectivity for the reaction using (sp)PdCl2 (14) without added ligand was also diminished, we believe this is a result of (−)-sparteine (1) decomplexation in the absence of excess ligand

- 36.References describing C1 symmetric ligand in asymmetric processes: Resconi L, Cavallo L, Fait A, Piemontesi F. Chem Rev. 2000;100:1253. doi: 10.1021/cr9804691.Helmchen G, Pfaltz A. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:336. doi: 10.1021/ar9900865.Williams JMJ. Synlett. 1996:705.Hatano M, Tamanaka M, Mikami K. Eur J Org Chem. 2003:2552.Nozaki K, Komaki H, Kawashima Y, Hiyama T, Matsubara T. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:534. doi: 10.1021/ja001395p.Kocovsky P, Vyskocil S, Smrcina M. Chem Rev. 2003;103:3213. doi: 10.1021/cr9900230.Bolm C, Verruci M, Simic O, Cozzi PG, Raabe G, Okamura H. Chem Commun. 2003:2826. doi: 10.1039/b309556h.Ohashi A, Kikuchi Si, Yasutake M, Imamoto T. Eur J Org Chem. 2002:2535.Hoge G, Wu HP, Kissel WS, Pflum DA, Greene DJ, Bao J. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5966. doi: 10.1021/ja048496y.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental details, x-ray data, enlarged schemes from the text, and NMR spectra are available free of charge.