Abstract

The human immune system has evolved to recognize antigenic diversity, a strength that has been harnessed by vaccine developers to combat numerous pathogens (e.g. pneumococcus, influenza virus, rotavirus). In each case, vaccine cocktails were formulated to include antigenic variants of the target. To combat HIV-1 diversity, we assembled a cocktail vaccine comprising dozens of envelopes, delivered as recombinant DNA, vaccinia virus and protein for testing in a clinical trial. One vaccinee has now completed vaccinations with no serious adverse events. Preliminary analyses demonstrate early proof-of-principle that a multi-envelope vaccine can elicit neutralizing antibody responses toward heterologous HIV-1 in humans.

Keywords: Vaccine development, HIV, multi-envelope, DNA-vaccinia virusprotein

Introduction

In late 2007, after more than 25 years of research, the HIV-1 field received news that another prominent vaccine candidate had failed in clinical testing [1]. This news has prompted much debate among investigators in the field and a renewed examination of basic immunological concepts as they pertain to HIV-1 vaccine design. Concepts to be discussed in this article include: (i) immune potential, (ii) challenges posed by HIV-1, (iii) evidence that protective immunity toward retroviruses can be generated in primates, and (iv) results from preclinical and clinical testing of a DNA-vaccinia virus-protein (D-V-P) multi-envelope vaccine.

Review

Immune potential

Humans possess a powerful immune system with which they can combat an enormous array of pathogens [2]. The system consists of billions of lymphocytes, subdivided into B- and T-cell populations. Unique recombination/splicing events at the nucleic acid level occur in each developing cell, combining V (variable), D (diversity), J (joining) and C (constant) regions to create a unique receptor on each cell surface. The cells recognize each of their targets with extraordinary precision. The antibodies on B-cells bind antigens with a lock-and-key type interaction (as illustrated by the cartoon in Figure 1), and with the help of innate immune effectors, can rapidly destroy a pathogen. T-cells are classically known for their ability to recognize viral peptides in association with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins (by a lock-and-key type interaction with T-cell receptors (TCR)). T-cells generally kill virus-infected cells and ‘help’ their B-cell partners. Together, the B-cell and T-cell populations present a formidable barrier to infection and disease [2].

Figure 1. Immune responses are precise.

A cartoon portrays three different antigens and corresponding antibody binding sites. Lock-and-key type interactions ensure the specificity of antibodies for their antigens. While each individual antibody is limited in its binding capacity, a combination of antibodies can tackle antigenic diversity.

Although lymphocyte populations are well equipped to destroy invading pathogens, they often exist in a resting state, unable to combat an immediate threat. A pathogen mimic or look-a-like can therefore be used as a vaccine to activate (prime) B- and T-cell populations before an actual pathogen exposure occurs. Vaccination triggers appropriate B- and T-cells by engaging cell-surface receptors (antibodies on B-cells and TCR on T-cells) with a perfect ‘fit’ for the antigen. Upon stimulation, these antigen-specific lymphocytes will proliferate and, in the case of B-cells, will secrete antibodies into the blood and lymph. The priming process yields effector and memory cells that can persist for the lifetime of a vaccinee [3].

Edward Jenner, who was unaware of the details of immune mechanisms, was the first to formally demonstrate vaccine efficacy. Jenner noted that milkmaids who experienced cowpox lesions were protected from smallpox infections. His deliberate inoculation of a young boy with cowpox, followed later by a smallpox challenge, proved that protection against a serious human pathogen could be conferred by vaccination. It was almost two centuries later when the details of lymphocyte function and the similarities between cowpox and smallpox were sufficiently understood to explain why an inoculation with one virus could protect against another. Jenner's success was assisted by the low mutation rate of the smallpox virus and the associated stability of its viral antigens [4]. Ultimately, the Jenner vaccine was the first (and remains the only) vaccine to eradicate a human disease [5].

Some other pathogens present vaccine developers with a more difficult task, because their antigens can vary from one isolate to the next. In this case, lymphocytes that are able to respond to one form of the pathogen may not respond to another and vaccines representing only one form of the pathogen may fail (as shown in Figure 1, one antibody cannot bind all three antigens). This problem has been solved in a number of fields by the creation of antigen cocktails. Cocktail vaccines activate a variety of lymphocytes with differing specificities that collectively prevent infection and disease. Examples of licensed cocktail vaccines include those against influenza virus, rotavirus, papillomavirus, poliovirus and pneumococcus [6-8].

Challenges posed by HIV-1

HIV-1 is a highly diverse pathogen because it carries an error-prone reverse transcriptase and lacks a polymerase-related proof-reading function [9;10]. An alignment of HIV-1 sequences reveals considerable diversity within both external and internal viral proteins [11]. As described above, a single-component vaccine is undesirable in this instance, as variant pathogens will easily escape a focused immune response, both at the B-cell and T-cell level [12;13]. In some cases, a single amino acid change may be sufficient to assist virus immune escape from B-cell or T-cell activities [14].

To combat diversity, scientists in the HIV-1 field have sought to define conserved structures on the pathogen, against which rare lymphocytes with broadly cross-reactive immune responses might be generated. Strategies have included: (1) the isolation of conserved sequences from the V3 loop of GP120 [15], (2) fusion of CD4 to envelope to expose an inducible neutralizing determinant [16], (3) removal of variable loops from envelope [17], (4) use of internal rather than external proteins (as in the recent clinical trial conducted by Merck [1]), and (5) creation of consensus or ancestral sequences [17-20]. Investigators have designed these vaccines with the hope that they will activate rare lymphocytes with a capacity to recognize all viruses. There are, in fact, a few monoclonal antibodies that neutralize many (albeit not all) HIV-1 isolates [21;22], and some T-cells respond to peptides that are highly conserved. However, these strategies have met with difficulty. While it may be possible to present conserved HIV-1 fragments to the immune system by vaccination, this does not ensure that the same regions will be exposed at the time of HIV-1 challenge. If a conserved region is hidden from the immune system during the infectious process or is not entirely conserved, responses toward this region may have limited effect. An additional difficulty is that conserved regions of HIV-1 can mimic ‘self’ antigens so that immune responses are inhibited by the natural mechanisms of self-tolerance [23].

The formulation of diverse antigen cocktails, as has been accomplished in other fields, provides an alternative vaccine strategy to the search for rare cross-reactive lymphocyte receptors. This strategy has not reached the forefront of the HIV-1 vaccine field, perhaps because of the overwhelming sequence diversity associated with HIV-1. The appeal of a vaccine cocktail approach is evident only when differences between ‘sequence’ and ‘antigen’ are considered. Indeed, proteins with extensive diversity at the amino acid sequence level often share antigenic structure [24]. Conversely, a single amino acid change can significantly alter a protein's antigenic structure [14;25]. Of interest, protein structural features can influence both B-cell and T-cell responses. We have observed, for example, that the sharing of a particular T-cell target peptide sequence between vaccine and virus does not ensure T-cell cross-reactivity [26]. The explanation relates in part to the processing mechanisms required for T-cell antigen presentation. Because T-cells are triggered by a complex of viral peptide and MHC, the viral peptides must be separated by cleavage from their parent proteins in the antigen presenting cell (APC, [2]). This cleavage may be influenced by structures flanking or distant from the T-cell target peptide [26;27]. Cleavage will also be affected by the mode of antigen entry into the APC, because the trafficking of antigen within the cell influences its contact with cellular proteases.

Given the complexities described above, the formulation of currently licensed vaccines against variant pathogens has not relied on absolute sequence comparisons. Instead, researchers have grouped variant proteins or carbohydrates based on antigenicity (as defined by the immune response) and then assembled successful vaccine cocktails comprising one representative from each group [6;8].

Might HIV-1 proteins be grouped by antigenic diversity rather than sequence diversity to develop a successful vaccine? The answer is presumably ‘yes’, although the hypothesis has not yet been thoroughly tested. The HIV-1 proteins are constrained in their degree of antigenic variability because each protein must perform precise functions. For example, the outer envelope protein must bind the highly conserved human CD4 molecule [28]. It must also be capable of fusing virus and host cell membranes. While these activities may be mediated by more than one sequence and structure (as is also the case for other pathogens), the number of mutually exclusive B-cell and T-cell antigens need not be vast.

Evidence that protective immunity toward retroviruses can be generated in primates

Vaccine successes have been achieved in non-human primate models in a number of instances [29;30]. As one example, Hu et. al. prepared a vaccine composed of Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) envelope glycoprotein (the only virally encoded protein on the surface of the virus and the target of neutralizing antibodies). Four macaques were vaccinated with the envelope-based vaccine while four macaques served as controls. When later challenged with an infectious clone of SIV that expressed an envelope protein identical to that in the vaccine, all four vaccinated animals were protected from infection. In contrast, all control animals became infected [30]. This result showed that the primate immune system was fully capable of preventing infection with a retrovirus provided that the virus was matched by shape with the vaccine. When researchers used mismatched vaccine and virus, the results were less satisfying [31], illustrating the precision of the lock-and-key type interaction between lymphocytes and their antigens (Figure 1).

Non-human primates are also protected against heterologous retroviruses when their immune systems are exposed to antigenic diversity. This phenomenon is best demonstrated in animals that are first infected with SIV or SHIV and then challenged with a second virus [32]. In this case of live virus vaccination, immunity is likely acquired via a multi-step process. First, following retrovirus infection, some of the virus particles are sequestered in privileged sites (e.g., brain tissue), where they will remain permanently hidden from the immune system. B-cells and T-cells respond to and clear peripheral virus but cannot clear the sequestered particles. As sequestered virus thrives, it will mutate, release escape variants (bearing antigenically distinct proteins) into the periphery, and elicit de novo immune responses. Repetitive cycles of virus mutation, immune response and virus escape continue until lymphoyctes with qualitatively distinct receptors have responded to the different viral antigens that are compatible with infection [33;34]. The diverse lymphocytes may then work in concert to protect against virus challenge from an exogenous source. Even though the exogenous virus may be heterologous in terms of origin and sequence, the antigens between exogenous and endogenous viruses are the same, explaining immune cross-reactivity and protection. The protection of infected monkeys from superinfection has been repeatedly demonstrated [35-38]. These results provide sound evidence that primates have a capacity to generate absolute immunity against retrovirus infections.

In humans, superinfections are also rare although they can occur [39-41]. It is likely that these are most frequent in early and late stages of the disease. In early stages, the immune system has not yet been activated, while in late stages, virus destroys the once-activated cells. Of interest, an analysis of HIV-1 concordant partners showed no HIV-1 transfers between individuals, suggesting that each was protected against superinfections when exposed to virus from an exogenous source [39]. Defining the frequency of superinfections in humans is a topic of considerable debate, because virus exposure histories cannot be fully defined. The macaque studies (above) therefore provide the better illustration of protective anti-retroviral immunity in a primate system.

The ability of an infected person to protect against exogenous virus while failing to clear endogenous virus is a situation that typifies several pathogens, such as varicella zoster virus (VZV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Like HIV-1, VZV and EBV generate immunity against super-infections, but the same cells that block exogenous virus cannot clear virus from privileged sites [42]. Often, such viruses co-exist with the host for years or decades without incident. If, however, the immune system is compromised (perhaps as the result of an unrelated illness), virus re-activation can overwhelm the host. The fact that there are now licensed, successful VZV (and papillomavirus) vaccines demonstrates the necessity of activating immune cells before (not after) an exposure to virus. By blocking virus entry, vaccine-induced immunity can prevent acute infection, chronic infection and virus-mediated disease [43].

Results from preclinical and clinical testing of a DNA-vaccinia virus-protein (D-V-P) multi-envelope vaccine

To test the hypothesis that a cocktail vaccine may be necessary and sufficient to prevent HIV-1 infections in humans, we have formulated a multi-envelope vaccine comprising dozens of unique HIV-1 gp140 envelope antigens. HIV-1 envelopes were selected as the basis of this vaccine because envelope proteins stimulate both neutralizing B-cell and T-cell responses. The envelopes are delivered in the form of recombinant DNA (D), recombinant vaccinia virus (V) and recombinant purified protein (P). Our cocktails are designed to encompass antigenic diversity by including HIV-1 envelope variants as defined by: (a) different binding patterns with panels of monoclonal antibodies [44], (b) sequential appearance in infected persons (reflecting virus evolution within a host [33;34]), and (c) distinct subtypes. This first generation vaccine was designed to encompass a large number of proteins to ensure representation of numerous diverse antigens.

A list of some previous pre-clinical and clinical research projects associated with development of this multi-envelope D-V-P vaccine is shown in Table 1. Our studies included a demonstration that successive inoculations with envelope recombinant vaccines given in the order D, V and P elicited durable B-cell and T-cell responses [22;45-47]. We also showed that multi-envelope vaccines generated superior immune breadth compared to single-envelope vaccines (as has also been demonstrated by other groups [7;48-50]), that the inclusion of a minor component in a mixed vaccine was sufficient to elicit a type-specific immune response [51], and that the grouping of envelopes by subtype or origin did not always correlate with antigenicity (as also confirmed by work in other laboratories [52;53]). Finally, we demonstrated that a multi-envelope D-V-P vaccine could protect macaques from disease following challenge with a heterologous SHIV [54].

Table 1.

Development of a D-V-P multi-envelope vaccine

| Observations | Species | References |

|---|---|---|

| The D-V vaccination regimen was superior to immunizations with D or V alone | Mouse | Richmond et. al., 1997 [46] |

| The D-V-P vaccination regimen was superior to D-V | Mouse | Caver et. al., 1998 [47] |

| Stambas et. al., 2005 [45] | ||

| Hurwitz et. al, 2008 [70] | ||

| Greater immune breadth was elicited by multi-envelope vaccines compared to single-envelope vaccines | Chimpanzee | Lockey et. al., 2000 [22] |

| Mouse | Zhan et. al., 2003 [71] | |

| Cotton rat | Hurwitz et. al., 2005 [7] | |

| Immune responses were generated toward a minor component of a mixed vaccine | Mouse | Zhan et. al., 2004 [51] |

| Antigenic relationships among HIV-1 envelope proteins were found to differ from relationships defined by clade/subtype or geographical origin | Mouse | Rencher et. al., 1997 [72] |

| D'Costa et. al., 2001 [14] | ||

| Slobod et. al., 2005 [44] | ||

| Brown et. al., 2006 [73] | ||

| Sealy et. al., 2008 [26] | ||

| Protection against heterologous SHIV challenge was conferred by a D-V-P multi-envelope vaccine | Macaque | Zhan et. al., 2005 [54] |

| Individually vectored vaccines were demonstrated to be safe and immunogenic in clinical trials | Human | Slobod et. al., 2004 [62] |

| Hurwitz et. al., 2008 [61] |

A number of independent groups have similarly adopted the strategy of formulating cocktails to represent variant HIV-1. As examples, Zolla-Pazner et. al. have created cocktail vaccines with an emphasis on triggering responses toward the V3 loop of HIV-1 envelope [55] while Azizi et. al. [56] and Dong et. al. [57] have designed peptide cocktails targeting V3 and non-V3 determinants in envelope and gag proteins. Still other investigators (e.g. Kong et. al. [49], Chakrabarti et. al.,[58], Rollman et. al. [59], and Pal et. al.[60]) have created cocktails based predominantly on viral subtypes (defined by absolute sequence comparisons [52;53]).

Our promising pre-clinical results encouraged advancement of the D-V-P multi-envelope approach to clinical trials. First, we tested D, V and P vaccines separately for safety. Each delivery vehicle was well tolerated [61;62]. We expected, based on our small animal studies, that robust immune responses would not be elicited toward these single-vectored vaccines. Indeed, immune responses toward the DNA vaccine were difficult to detect (unpublished data). However, the V vaccine elicited sporadic envelope-specific responses [62] and the protein vaccine elicited responses in every study participant [61]. Some participants who received the V and P vaccines have retained HIV-1-specific immune responses for 3 years or more.

After having demonstrated that each of the vectors was safe in clinical trials, we sought and received FDA and IRB approvals for the testing of the combination D-V-P multi-envelope cocktail. The protocol was designed to administer more than 50 envelope proteins with inoculations (D-D-V-P-D-P) given at monthly intervals. The D vaccine encompassed 51 recombinant plasmids each expressing a different envelope protein, administered as an intramuscular inoculation of 100 micrograms; the V vaccine encompassed 23 recombinant viruses, each expressing a different envelope protein, administered by subcutaneous inoculation with 107 total plaque forming units; the recombinant CHO-derived protein vaccine was 100 microgram purified envelope from HIV-1 isolate UG92005, administered IM as a formulation with 500 micrograms alum.

One individual has thus far completed the full 6-shot inoculation regimen (D-D-V-P-D-P; inoculations were administered at monthly intervals over the course of a 5 month period). All 6 inoculations were well tolerated. Adverse events that were possibly, probably or definitely vaccine related were grade 1 only and included pain, erythema, pruritis or warmth at the injection sight, headache, fatigue and myalgia.

Preliminary tests of envelope-specific immune responses were initiated using the Abbott clinical enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (HIVAB HIV-1/HIV-2 (recombinant DNA) Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA). A significant antibody binding response toward a heterologous antigen was first identified at month 5 after the participant had received 5 immunizations (D-D-V-P-D). By month 6 (1 month after completion of the entire vaccination regimen), the response was 10-fold improved (yielding peak absorbance levels in the Abbott assay, O.D. 450nm >2). The binding results encouraged an assessment of neutralizing activity.

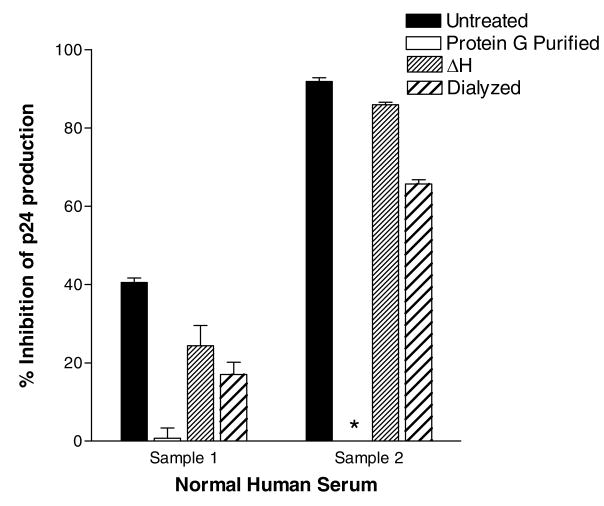

Prior to the conduct of neutralization tests with vaccinee sera, we observed that normal human serum could be highly inhibitory for HIV-1 growth. This finding had been described by other researchers as well; they found that the degree of virus growth inhibition by serum was not constant even among longitudinal samples from a single subject, and could render neutralization assays impossible to interpret [63;64]. To remove non-specific activity from human blood samples, we tested a number of methodologies, beginning with the pre-absorption of sera on target cells. However, while the technique reduced non-specific activity in some samples, complete and predictable removal was not consistent (data not shown). We therefore treated sera with other methods including heat (56° C [65]), dialysis, and chromatography with protein G columns. Neutralization assays were then performed with treated and untreated samples from HIV-1 negative individuals. Assays were conducted by incubating antibody samples with HIV-1IIIB for 1 hour at 37°C, followed by the addition of the serum/virus mixtures to confluent CXCR4-GHOST cells for overnight culture. Cells were washed and incubated for two additional days, after which supernatants were removed for p24 assays (p24 ELISA kit, ImmunoDiagnostics, Woburn, MA, USA).

Results are shown in Figure 2 with two different serum samples from HIV-1-negative individuals tested at final serum dilutions of 1:10. The ‘% inhibition’ values were defined by comparing test samples with negative control wells containing no serum products. As demonstrated, results confirmed that serum samples from HIV-1-negative individuals could be highly inhibitory for virus growth. We also found that the purification of immunoglobulin with protein G columns reproducibly removed non-specific activities from serum samples. This method was superior to other methods such as heat treatment or dialysis.

Figure 2. Protein G purification removes non-specific virus-inhibitory activities from human blood samples.

Antibody neutralization assays were conducted with serum from two HIV-1-negative individuals (provided by the Tennessee Blood Services (Memphis, TN) and from an IRB-approved protocol at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital). Sera were unprocessed or processed by three different methods: (1) Purification of immunoglobulin on a protein G column: Sera were diluted in PBS (1:10) and the samples were then processed over 0.5 ml columns of Protein G- Sepharose 4B (Sigma-Aldrich). The columns were washed with twenty column volumes of PBS, after which the immunoglobulins were eluted with 0.2M Glycine, pH 2.8. Samples were dialyzed overnight in PBS. (2) Heat inactivation (ΔH): Sera were heated in a 56°C water bath for 30 min. (3) Dialysis: Sera were dialyzed overnight in PBS (Slide-A-Lyzer Dialysis Cassette, molecular weight cutoff 10,000 kD, Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). All samples were filtered through an 0.2μM membrane (Whatmann 3mm, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) prior to testing. Each antibody sample was mixed with virus (approximately 50 TCID50/well HIV-1IIIB) in a 96 well round bottom plate (Sarstedt, Newton, NC, USA) in 100 μl tissue culture medium (RPMI 1640 with 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum [Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA, USA], penicillin, streptomycin and supplemental glutamine). The final serum dilution in the antibody-virus mixture was 1:10 (processed samples were brought to their original serum volume and diluted 1:10). The HIV-1IIIB was provided by Dr. R.V. Srinivas and the NIH AIDS Reference Reagent Program (NARRP). Samples were incubated for 1 hr at 37°C, 5% CO2. Well contents were next transferred to GHOST cell monolayers in 96 well flat bottom plates (Sarstedt, GHOST cell culture media were removed from adherent monolayers immediately prior to transfer) and incubated overnight (37°C, 5% CO2). Wells were washed twice and then incubated for an additional 2 days. Supernatants were removed and assayed for p24 by ELISA (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA or ImmunoDiagnostics). The “% inhibition” of p24 values was calculated by comparing test wells with negative controls (virus cultures without serum). Samples were tested in duplicate. An asterisk indicates that there was no inhibition of virus growth. Standard error bars are shown.

The protein-G columns were also used for the preparation of samples from HIV-1-seropositive blood samples. This work showed that authentic neutralizing antibody activity was retained after immunoglobulin purification (e.g. an unmanipulated HIV-1-positive serum sample scored 68% and 99% neutralization at dilutions of 1:1000 and 1:100, respectively; the same sample scored 65% and 100% neutralization at dilutions of 1:1000 and 1:100, respectively, after the antibody was purified and reconstituted to its original serum volume). Based on this information, we chose to purify immunoglobulins from all test and control blood samples before initiating studies of the vaccinee. We also tested antibodies with and without added complement, because complement can assist antibody activity [2]. The supplement was necessary because complement can be damaged during blood processing and is specifically removed by immunoglobulin purification.

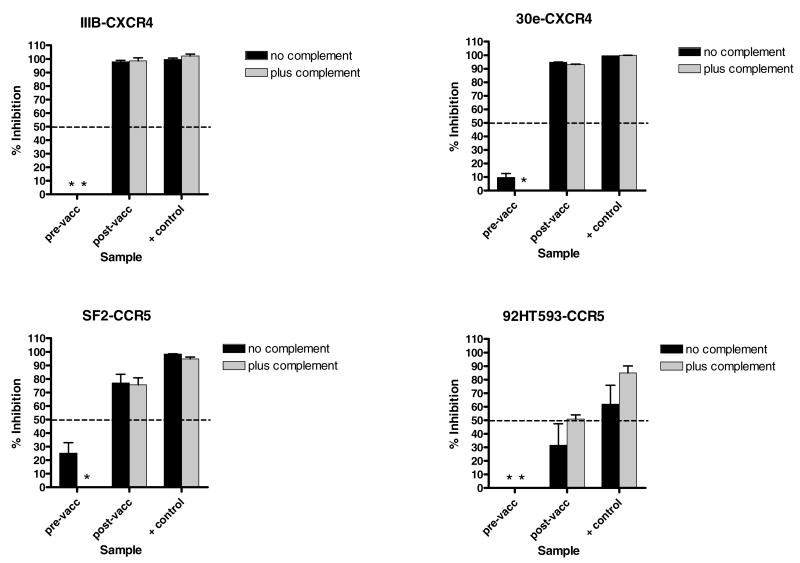

To test vaccinee blood, we examined blood samples taken prior to vaccination and 1 month after the final vaccination. Antibodies were purified from both samples on protein G columns and reconstituted to their original plasma volume. Purified immunoglobulin (at a 1:5 final dilution) was incubated overnight with a number of different heterologous viruses (approximately 10 TCID50 HIV-1 per test) with and without complement (5% final concentration, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA). The virus-antibody mixtures were then added to monolayers of GHOST cells (either CXCR4-GHOST cells for HIV-1IIIB and HIV-130e viruses, or CCR5-GHOST cells, for HIV-1SF2 and HIV-192HT593 viruses). After an overnight incubation, the cells were washed and cultured for an additional 2 days and supernatants were tested for p24. The positive control was pooled antibody from HIV-1 infected individuals (processed by protein G column purification and tested at a final dilution of 1:100 relative to the original serum volume).

Results are shown in Figure 3. The ‘% inhibition’ values were defined by comparing test samples with negative control wells containing 0% or 5% complement (designated ‘no complement’ or ‘plus complement’) and a 1:100 dilution of purified human serum immunoglobulin from an HIV-1 uninfected individual. We found that four different viruses (representing both X4 and R5 subtypes) were neutralized by the positive control and by the vaccine sample to a level of >50%. Neutralization was evident even though the virus envelopes were heterologous to those in the vaccine. In the case of virus 92HT593, 50% neutralization was achieved only when complement was added to the cultures. Four additional virus stocks (HIV-196ZM651, HIV-1ZM53M, HIV-192UG029 and HIV-193UG082) were also tested. For these viruses, neutralization by the positive control was absent or was relatively weak compared to the first four viruses, and responses by the vaccinee were below 50% (data not shown). The failure of certain viruses to be neutralized in vitro need not predict a failure in vivo as demonstrated by Van Rompay et. al. in an SIV system [66]. Studies are ongoing to explain inherent discrepancies between virus neutralization assays [67], and to define elusive ‘correlates of protection’.

Figure 3. Neutralization activity elicited by D-V-P vaccination.

Samples from the vaccinee were collected prior to vaccination and 1 month after the completion of the D-D-V-P-D-P vaccination regimen. Samples were then purified on Protein G columns and reconstituted to original plasma volumes. Purified immunoglobulin (at a 1:5 final dilution) was mixed with a number of different subtype B infectious HIV-1 stocks with or without complement (5% final concentration, Calbiochem) for overnight incubation. The virus-antibody mixture was then added to a monolayer of GHOST cells. After an overnight incubation, the cells were washed and cultured for an additional 2 days and supernatants were tested for p24. The positive control was pooled purified serum immunoglobulin from HIV-1 infected individuals (tested at a 1:100 final dilution relative to the original serum volume). The “% inhibition” of p24 values was calculated by comparing test wells with negative control wells. Negative control wells were virus cultures incubated with or without 5% complement and with purified immunoglobulin from an HIV-1-uninfected blood donor (immunoglobulin was diluted 1:100 relative to the original serum volume). Samples were tested in duplicate. An asterisk indicates that there was no inhibition of virus growth. Standard error bars are shown.

Despite the preliminary nature of our neutralization studies, the significant results with four viruses provides early proof-of-principle that an envelope-based vaccine need not match envelope sequence with a target virus to elicit cross-neutralizing activity. This concept is supported by a larger body of pre-clinical trial data from our lab (Table 1) and the research of others, and forms the basis for the design of successful vaccines against other variant pathogens; if proteins in the vaccine and the target virus are antigenically similar, there will be cross-reactivity. Our results encourage a further development of cocktail vaccines with which prevention of HIV-1 infections in humans might ultimately be achieved.

Conclusion

History has shown that a diverse pathogen can be adequately represented with a manageable cocktail of vaccine antigens. This is in part due to the fact that non-identical amino acid sequences may fold to yield similar three-dimensional antigenic conformations. Despite enormous HIV-1 sequence diversity, the immune system might recognize HIV-1 isolates as comprising only a small number of discrete antigenic groups. Representation of these groups in a vaccine cocktail may be necessary and sufficient for successful vaccine design. As investigators struggle with recent disappointments in the vaccine field, one may remember the pessimistic viewpoints that once surrounded polio vaccine development [68;69]. Polio virus has since been eradicated from most regions of the world, due to the formulation and distribution of a cocktail vaccine. Attention to these types of successes may ultimately assist the development of a successful vaccine and consequent prevention of HIV-1 infections in humans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Harold Stamey from the Tennessee Blood Services for providing samples for this study, Dr. R. Srinivas, the NIH AIDS Reference Reagent Program (NARRP, Rockville, MD) and the World Health Organization Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization, for providing viruses, and Drs. Kewalramani and Littman and the NARRP for providing the GHOST cells. We thank Dr. Randy Hayden (Pathology Department, St Jude) for the conduct of Abbott ELISAs. We thank Sharon Naron (Scientific Editing, St Jude) for critical editorial review. This work was supported in part by NIH NIAID P01-AI45142, the Federated Department Stores, the Mitchell Fund, the Carl C. Anderson Sr. and Marie Joe Anderson Charitable Foundation, the Pendleton Fund, the Pioneer Fund and the American Lebanese Syrian-Associated Charities (ALSAC).

References

- 1.News in Brief. HIV vaccine failure prompts Merck to halt trial. Nature. 2007;449:390. doi: 10.1038/449390c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy K, Travers P, Walport M. Janeway's Immunobiology. Garland Science; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammarlund E, Lewis MW, Hansen SG, Strelow LI, Nelson JA, Sexton GJ, Hanifin JM, Slifka MK. Duration of antiviral immunity after smallpox vaccination. Nat Med. 2003;9:1131–1137. doi: 10.1038/nm917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Carroll DS, Gardner SN, Walsh MC, Vitalis EA, Damon IK. On the origin of smallpox: correlating variola phylogenics with historical smallpox records. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15787–15792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609268104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenner F, Henderson DA, Arita I, Jezek Z, Ladnyi ID. Smallpox and its eradication. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark HF, Offit PA, Plotkin SA, Heaton PM. The new pentavalent rotavirus vaccine composed of bovine (strain WC3) -human rotavirus reassortants. Pediatr Infect DIs J. 2006;25:577–583. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000220283.58039.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurwitz JL, Slobod KS, Lockey TD, Wang S, Chou TH, Lu S. Application of the Polyvalent Approach to HIV-1 Vaccine Development. Curr Drug Targets Infect Disord. 2005;5:143–156. doi: 10.2174/1568005054201517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biagini RE, Schlottmann SA, Sammons DL, Smith JP, Snawder JC, Striley CA, MacKenzie BA, Weissman DN. Method for simultaneous measurement of antibodies to 23 pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10:744–750. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.5.744-750.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preston BD, Poiesz BJ, Loeb LA. Fidelity of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Science. 1988;242:1168–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.2460924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts JD, Bebenek K, Kunkel TA. The accuracy of reverse transcriptase from HIV-1. Science. 1988;242:1171–1173. doi: 10.1126/science.2460925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanabani S, Neto WK, de Sa Filho DJ, Diaz RS, Munerato P, Janini LM, Sabino EC. Full-length genome analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C in Brazil. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22:171–176. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barouch DH, Kunstman J, Glowczwskie J, Kunstman KJ, Egan MA, Peyerl FW, Santra S, Kuroda MJ, Schmitz JE, Beaudry K, Krivulka GR, Lifton MA, Gorgone DA, Wolinsky SM, Letvin NL. Viral escape from dominant simian immunodeficiency virus epitope-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in DNA-vaccinated rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 2003;77:7367–7375. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7367-7375.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berman PW, Gray AM, Wrin T, Vennari JC, Eastman DJ, Nakamura GR, Francis DP, Gorse G, Schwartz DH. Genetic and immunologic characterization of viruses infecting MN-rgp120-vaccinated volunteers. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:384–397. doi: 10.1086/514055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Costa S, Slobod KS, Webster RG, White SW, Hurwitz JL. Structural features of HIV envelope defined by antibody escape mutant analysis. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17:1205–1209. doi: 10.1089/088922201316912808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White-Scharf ME, Potts BJ, Smith LM, Sokolowski KA, Rusche JR, Silver S. Broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to the V3 region of HIV-1 can be elicited by peptide immunization. Virology. 1993;192:197–206. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaCasse RA, Follis KE, Trahey M, Scarborough JD, Littman DR, Nunberg JH. Fusion-competent vaccines: broad neutralization of primary isolates of HIV (Retraction (2002) Science 296: 1025) Science. 1999;283:357–362. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnett SW, Srivastava IK, Ulmer JB, Donnelly JJ, Rappuoli R. Development of V2-deleted trimeric envelope vaccine candidates from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) subtypes B and C. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:1386–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaRosa GJ, Davide JP, Weinhold K, Waterbury JA, Profy AT, LEwis JA, Lanlois AJ, Dreesman GR, Boswell RN, Shadduck P, Holley LH, Karplus M, Bolognesi DP, Matthews TJ, Emini EA, Putney SD. Conserved sequence and structural elements in the HIV-1 principal neutralizing determinant. Science. 1990;249:932–935. doi: 10.1126/science.2392685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Javaherian K, Langlois AJ, LaRosa GJ, Profy AT, Bolognesi DP, Herlihy WC, Putney SD, Matthews TJ. Broadly neutralizing antibodies elicited by the hypervariable neutralizing determinant of HIV-1. Science. 1990;250:1590–1593. doi: 10.1126/science.1703322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaschen B, Taylor J, Yusim K, Foley B, Gao F, Lang D, Novitsky V, Haynes B, Hahn BH, Bhattacharya T, Korber B. Diversity considerations in HIV-1 vaccine selection. Science. 2002;296:2354–2360. doi: 10.1126/science.1070441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conley AJ, Kessler JA, II, Boots LJ, Tung JS, Arnold BA, Keller PM, Shaw AR, Emini EA. Neutralization of divergent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants and primary isolates by IAM-41-2F5, an anti-gp41 human monoclonal antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1994;91:3348–3352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lockey TD, Slobod KS, Caver TE, D'Costa S, Owens RJ, McClure HM, Compans RW, Hurwitz JL. Multi-envelope HIV vaccine safety and immunogenicity in small animals and chimpanzees. Immunol Res. 2000;21:7–21. doi: 10.1385/IR:21:1:7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haynes BF, Fleming J, Clair EW, Katinger H, Stiegler G, Kunert R, Robinson J, Scearce RM, Plonk K, Staats HF, Ortel TL, Liao HX, Alam SM. Cardiolipin polyspecific autoreactivity in two broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. Science. 2005;308:1906–1908. doi: 10.1126/science.1111781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright PF, Neumann g, Kawaoka Y. Orthomyxoviruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. 5th. Williams and Wilkins, Lippincott; Philadelphia, PA: 2008. pp. 1671–1740. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerhard W, Yewdell J, Frankel ME, Webster R. Antigenic structure of influenza virus haemagglutinin defined by hybridoma antibodies. Nature. 1981;290:713–717. doi: 10.1038/290713a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sealy R, Chaka W, Surman S, Brown SA, Cresswell P, Hurwitz JL. Target peptide sequence within infectious human immunodeficiency virus type 1 does not ensure envelope-specific T-helper cell reactivation: influences of cysteine protease and gamma interferon-induced thiol reductase activities. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:713–719. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00412-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moudgil KD, Sercarz EE, Grewal IS. Modulation of the immunogenicity of antigenic determinants by their flanking residues. Immunol Today. 1998;19:217–220. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet RW, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berman PW, Gregory TJ, Riddle L, Nakamura GR, Champe MA, Porter JP, Wurm FM, Hershberg RD, Cobb EK, Eichberg JW. Protection of chimpanzees from infection by HIV-1 after vaccination with recombinant glycoprotein gp120 but not gp160. Nature. 1990;345:622–625. doi: 10.1038/345622a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu SL, Abrams K, Barber GN, Moran P, Zarling JM, Langlois AJ, Kuller L, Morton WR, Benveniste RE. Protection of macaques against SIV infection by subunit vaccines of SIV envelope glycoprotein gp160. Science. 1992;255:456–459. doi: 10.1126/science.1531159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polacino P, Stallard V, Klaniecki JE, Montefiori DC, Langlois AJ, Richardson BA, Overbaugh J, Morton WR, Benveniste RE, Hu SL. Limited breadth of the protective immunity elicited by simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmne gp160 vaccines in a combination immunization regimen. J Virol. 1999;73:618–630. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.618-630.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wyand MS, Manson K, Montefiori DC, Lifson JD, Johnson RP, Desrosiers RC. Protection by live, attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus against heterologous challenge. J Virol. 1999;73:8356–8363. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8356-8363.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wrin T, Crawford L, Sawyer L, Weber P, Sheppard HW, Hanson CV. Neutralizing antibody responses to autologous and heterologous isolates of human immunodeficiency virus. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:211–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richman DD, Wrin T, Little SJ, Petropoulos CJ. Rapid evolution of the neutralizing antibody response to HIV type 1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4144–4149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630530100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daniel MD, Kirchhoff F, Czajak SC, Sehgal PK, Desrosiers RC. Protective effects of a live attenuated SIV vaccine with a deletion in the nef gene. Science. 1992;258:1938–1941. doi: 10.1126/science.1470917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cranage MP, Whatmore AM, Sharpe SA, Cook N, Polyanskaya N, Leech S, Smith JD, Rud EW, Dennis MJ, Hall GA. Macaques infected with live attenuated SIVmac are protected against superinfection via the rectal mucosa. Virology. 1997;229:143–154. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephens EB, Joag SV, Atkinson B, Sahni M, Li Z, Foresman L, Adany I, Narayan O. Infected macaques that controlled replication of SIVmac or nonpathogenic SHIV developed sterilizing resistance against pathogenic SHIV(KU-1) Virology. 1997;234:328–339. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Titti F, Sernicola L, Geraci A, Panzini G, Di Fabio S, Belli R, Monardo F, Borsetti A, Maggiorella MT, Koanga-Mogtomo M, Corrias F, Zamarchi R, Amadori A, Chieco-Bianchi L, Verani P. Live attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus prevents super-infection by cloned SIVmac251 in cynomolgus monkeys. J Gen Virol. 1997;78(Pt 10):2529–2539. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-10-2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chakraborty B, Valer L, De MC, Soriano V, Quinones-Mateu ME. Failure to detect human immunodeficiency virus type 1 superinfection in 28 HIV-seroconcordant individuals with high risk of reexposure to the virus. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20:1026–1031. doi: 10.1089/aid.2004.20.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gonzales MJ, Delwart E, Rhee SY, Tsui R, Zolopa AR, Taylor J, Shafer RW. Lack of detectable human immunodeficiency virus type 1 superinfection during 1072 person-years of observation. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:397–405. doi: 10.1086/376534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altfeld M, Allen TM, Yu XG, Johnston MN, Agrawal D, Korber BT, Montefiori DC, O'Connor DH, Davis BT, Lee PK, Maier EL, Harlow J, Goulder PJ, Brander C, Rosenberg ES, Walker BD. HIV-1 superinfection despite broad CD8+ T-cell responses containing replication of the primary virus. Nature. 2002;420:434–439. doi: 10.1038/nature01200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rickinson AB, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Martin MA, Lamb RA, Roizman B, Straus SE, editors. Fields Virology. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2001. pp. 2575–2627. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldman GS. Incidence of herpes zoster among children and adolescents in a community with moderate varicella vaccination coverage. Vaccine. 2003;21:4243–4249. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slobod KS, Coleclough C, Bonsignori M, Brown SA, Zhan X, Surman S, Zirkel A, Jones BG, Sealy RE, Stambas J, Brown B, Lockey TD, Freiden PJ, Doherty PC, Blanchard JL, Martin LN, Hurwitz JL. HIV Vaccine Rationale, Design and Testing. Curr HIV Res. 2005;3:107–112. doi: 10.2174/1570162053506928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stambas J, Brown SA, Gutierrez A, Sealy R, Yue W, Jones B, Lockey TD, Zirkel A, Freiden P, Brown B, Surman S, Coleclough C, Slobod KS, Doherty PC, Hurwitz JL. Long lived multi-isotype anti-HIV antibody responses following a prime-double boost immunization strategy. Vaccine. 2005;23:2454–2464. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richmond JFL, Mustafa F, Lu S, Santoro JC, Weng J, O'Connell M, Fenyo EM, Hurwitz JL, Montefiori DC, Robinson HL. Screening of HIV-1 Env glycoproteins for the ability to raise neutralizing antibody using DNA immunization and recombinant vaccinia virus boosting. Virology. 1997;230:265–274. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caver TE, Lockey TD, Srinivas RV, Webster RG, Hurwitz JL. A novel vaccine regimen utilizing DNA, vaccinia virus and protein immunizations for HIV-1 envelope presentation. Vaccine. 1999;17:1567–1572. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00355-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ljungberg K, Rollman E, Eriksson L, Hinkula J, Wahren B. Enhanced immune responses after DNA vaccination with combined envelope genes from different HIV-1 subtypes. Virology. 2002;302:44–57. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kong WP, Huang Y, Yang ZY, Chakrabarti BK, Moodie Z, Nabel GJ. Immunogenicity of multiple gene and clade human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA vaccines. J Virol. 2003;77:12764–12772. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.23.12764-12772.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cho MW, Kim YB, Lee MK, Gupta KC, Ross W, Plishka R, Buckler-White A, Igarashi T, Theodore T, Byrum R, Kemp C, Montefiori DC, Martin MA. Polyvalent envelope glycoprotein vaccine elicits a broader neutralizing antibody response but is unable to provide sterilizing protection against heterologous simian/human immunodeficiency virus infection in pigtailed macaques. J Virol. 2001;75:2224–2234. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2224-2234.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhan X, Slobod KS, Surman S, Brown SA, Coleclough C, Hurwitz JL. Minor components of a multi-envelope HIV vaccine are recognized by type-specific T-helper cells. Vaccine. 2004;22:1206–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moore JP, Cao Y, Leu J, Qin L, Korber B, Ho DD. Inter- and intraclade neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1:Genetic clades do not correspond to neutralization serotypes but partially correspond to gp120 antigenic serotypes. J Virol. 1996;70:427–444. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.427-444.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weber J, Fenyo EM, Beddows S, Kaleebu P, Bjorndal A. Neutralization serotypes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 field isolates are not predicted by genetic subtype. The WHO Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization. J Virol. 1996;70:7827–7832. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7827-7832.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhan X, Martin LN, Slobod KS, Coleclough C, Lockey TD, Brown SA, Stambas J, Bonsignori M, Sealy RE, Blanchard JL, Hurwitz JL. Multi-envelope HIV-1 vaccine devoid of SIV components controls disease in macaques challenged with heterologous pathogenic SHIV. Vaccine. 2005;23:5306–5320. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zolla-Pazner S, Gorny MK, Nyambi PN, VanCott TC, Nadas A. Immunotyping of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV): an approach to immunologic classification of HIV. J Virol. 1999;73:4042–4051. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4042-4051.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Azizi A, Anderson DE, Torres JV, Ogrel A, Ghorbani M, Soare C, Sandstrom P, Fournier J, az-Mitoma F. Induction of broad cross-subtype-specific HIV-1 immune responses by a novel multivalent HIV-1 peptide vaccine in cynomolgus macaques. J Immunol. 2008;180:2174–2186. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dong XN, Wu Y, Chen YH. The neutralizing epitope ELDKWA on HIV-1 gp41: genetic variability and antigenicity. Immunol Lett. 2005;101:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chakrabarti BK, Ling X, Yang ZY, Montefiori DC, Panet A, Kong WP, Welcher B, Louder MK, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ. Expanded breadth of virus neutralization after immunization with a multiclade envelope HIV vaccine candidate. Vaccine. 2005;23:3434–3445. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rollman E, Brave A, Boberg A, Gudmundsdotter L, Engstrom G, Isaguliants M, Ljungberg K, Lundgren B, Blomberg P, Hinkula J, Hejdeman B, Sandstrom E, Liu M, Wahren B. The rationale behind a vaccine based on multiple HIV antigens. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:1414–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pal R, Kalyanaraman VS, Nair BC, Whitney S, Keen T, Hocker L, Hudacik L, Rose N, Mboudjeka I, Shen S, Wu-Chou TH, Montefiori D, Mascola J, Markham P, Lu S. Immunization of rhesus macaques with a polyvalent DNA prime/protein boost human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine elicits protective antibody response against simian human immunodeficiency virus of R5 phenotype. Virology. 2006;348:341–353. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hurwitz JL, Lockey TD, Jones B, Freiden P, Sealy R, Coleman J, Howlett N, Branum K, Slobod KS. First phase I clinical trial of an HIV-1 subtype D gp140 envelope protein vaccine: immune activity induced in all study participants. AIDS. 2008;22:149–151. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f174ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Slobod KS, Lockey TD, Howlett N, Srinivas RV, Rencher SD, Freiden PJ, Doherty PC, Hurwitz JL. Subcutaneous administration of a recombinant vaccinia virus vaccine expressing multiple envelopes of HIV-1. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;23:106–110. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-1075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bures R, Gaitan A, Zhu T, Graziosi C, McGrath KM, Tartaglia J, Caudrelier P, El Habib R, Klein M, Lazzarin A, Stablein DM, Deers M, Corey L, Greenberg ML, Schwartz DH, Montefiori DC. Immunization with recombinant canarypox vectors expressing membrane-anchored glycoprotein 120 followed by glycoprotein 160 boosting fails to generate antibodies that neutralize R5 primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2000;16:2019–2035. doi: 10.1089/088922200750054756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lian Y, Srivastava I, Gomez-Roman VR, zur MJ, Sun Y, Kan E, Hilt S, Engelbrecht S, Himathongkham S, Luciw PA, Otten G, Ulmer JB, Donnelly JJ, Rabussay D, Montefiori D, van Rensburg EJ, Barnett SW. Evaluation of envelope vaccines derived from the South African subtype C human immunodeficiency virus type 1 TV1 strain. J Virol. 2005;79:13338–13349. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13338-13349.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hosoi S, Borsos T, Dunlop N, Nara PL. Heat-labile, complement-like factor(s) of animal sera prevent(s) HIV-1 infectivity in vitro. Journal of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. 1990;3:366–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van Rompay KK, Berardi CJ, Dillard-Telm S, Tarara RP, Canfield DR, Valverde CR, Montefiori DC, Cole KS, Montelaro RC, Miller CJ, Marthas ML. Passive immunization of newborn rhesus macaques prevents oral simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1247–1259. doi: 10.1086/515270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Louder MK, Sambor A, Chertova E, Hunte T, Barrett S, Ojong F, Sanders-Buell E, Zolla-Pazner S, McCutchan FE, Roser JD, Gabuzda D, Lifson JD, Mascola JR. HIV-1 envelope pseudotyped viral vectors and infectious molecular clones expressing the same envelope glycoprotein have a similar neutralization phenotype, but culture in peripheral blood mononuclear cells is associated with decreased neutralization sensitivity. Virology. 2005;339:226–238. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Burnet FM. Health Bulletin. Department of Health-Victoria; Australia: 1945. Poliomyelitis in the light of recent experimental work. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pallansch MA, Roos RP. In: Enteroviruses: Polioviruses, coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, and newer enteroviruses. Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE, editors. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2001. pp. 723–775. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hurwitz JL, Zhan X, Brown SA, Bonsignori M, Stambas J, Lockey TD, Sealy R, Surman S, Freiden P, Jones B, Martin L, Blanchard J, Slobod KS. HIV-1 vaccine development: Tackling virus diversity with a multi-envelope cocktail. Frontiers Bioscience. 2008;13:609–620. doi: 10.2741/2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhan X, Slobod KS, Surman S, Brown SA, Lockey TD, Coleclough C, Doherty PC, Hurwitz JL. Limited breadth of a T-helper cell response to a human immunodeficiency virus envelope protein. J Virol. 2003;77:4231–4236. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.7.4231-4236.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rencher SD, Hurwitz JL. Effect of natural HIV-1 envelope V1-V2 sequence diversity on the binding of V3 and non-V3-specific antibodies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1997;16:69–73. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199710010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brown SA, Slobod KS, Surman S, Zirkel A, Zhan X, Hurwitz JL. Individual HIV type 1 envelope-specific T cell responses and epitopes do not segregate by virus subtype. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22:188–194. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.