Abstract

CD40 plays important roles in cell-mediated and humoral immune responses. In this study, we explored mechanisms underlying lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced CD40 expression in purified human peripheral blood monocytic cells (PBMCs) from healthy volunteers. Exposure to LPS induced increases in CD40 mRNA and protein expression on PBMCs. LPS stimulation caused IκBα degradation. Inhibition of NFκB activation abrogated LPS-induced CD40 expression. LPS stimulation also resulted in phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases, however, only Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) was partially involved in LPS-induced CD40 expression. In addition, LPS exposure resulted in elevated interferon γ (IFNγ) levels in the medium of PBMCs. Neutralization of IFNγ and IFNγ receptor using specific antibodies blocked LPS-induced CD40 expression by 44% and 37%, respectively. In summary, LPS induced CD40 expression on human PBMCs through activation of NFκB and JNK, and partially through the induction of IFNγproduction.

Keywords: CD40, interferon γ, LPS, mitogen-activated protein kinase, NFκB

CD40 is a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family and is expressed on a variety of cell types, such as monocytes, B cells, macrophages, basophils, eosinophils, dendritic cells and endothelial cells [1]. The CD40 molecule is a phosphorylated glycoprotein with the structure of a typical type I transmembrane protein that is composed of 277 amino acids with a 193 amino acid extracellular domain, a 22 amino acid transmembrane domain, and a 62 amino acid intracellular tail [2]. Ligation of CD40 by its ligand, CD154, activates numerous signaling pathways leading to changes in gene expression and function. These signaling pathways include nuclear factor κB (NFκB), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), TNF receptor-associated factor proteins, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), and the janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway [3]. Signaling through CD40 up-regulates the expression of cell surface molecules such as class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC II), CD80, and CD86, adhesion molecules, secretion of cytokines and chemokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, IL-10, TNFα, and promotes prothrombotic activities and immunoglobulin class-switching to IgE [4, 5]. Thus, CD40 is not only critical in mediating normal immune responses, it also participates in a wide range of immune responses that have been associated with a variety of pathogenic processes in chronic inflammatory diseases that include asthma, autoimmune diseases, and atherosclerosis [6, 7].

In comparison to studies of CD40 signaling and function, less is known about the mechanisms that regulate human CD40 gene expression [4]. The CD40 gene is mapped to chromosome 20q11-q13 and expressed as a single 1.5 kb mRNA species. The CD40 promoter is a TATA-less promoter that contains three potential interferon (IFN) gamma activated sequence (GAS) elements. Other potentially relevant cis-regulatory elements in the human CD40 5′-flanking region are consensus sequences for NFκB, Ets family, activator protein-1 (AP-1), c-Myc, and Sp1 [8]. In mouse macrophages, transcription factors, such as NFκB, STAT-1α, PU.1, and Spi-B, have been shown to mediate CD40 induction after endotoxin or cytokine stimulation [4, 9, 10]. The human CD40 gene shares 62% amino acid identity in the complete coding sequence with the mouse CD40 gene [1, 11]. A previous study has shown that coarse, fine, and ultrafine air pollution particles increased immune costimulatory receptors including CD40, CD80, and CD86, and MHC class II molecules (HLA-DR) on human blood-derived monocytic cells [12]. Ensuing studies in our laboratory have indicated that LPS was an important component on air particles and responsible for particle-induced immune responses. The present study aimed to uncover the events regulating LPS-induced CD40 expression in normal human peripheral blood monocytic cells (PBMCs). Human PBMCs (composed of 93% monocytes and 7% lymphocytes) were isolated from healthy volunteers. We observed that LPS induced CD40 expression on human blood PBMCs through activation of NFκB and JNK, and partially through secreted IFNγ.

Materials and Methods

Materials and reagents

LPS (Escherichia coli 0127:B8 ) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO). SDS-PAGE supplies such as molecular mass standards and buffers were obtained from Bio-Rad (Richmond, CA). The mouse anti-human CD40-phycoerythrin (PE) and IgG1-PE antibodies were purchased from Beckman Coulter-Immunotech (Marseille, France). IFNγ neutralizing antibodies and ELISA assay kit were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). IFNγ receptor neutralizing antibody was obtained from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). Phospho-specific and pan antibodies against ERK, JNK, and p38, and IκBα antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). β-actin antibody was purchased from USBiological (Swampscott, MA). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse IgG were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Polymyxin B, the ERK kinase inhibitor PD98059, the p38 kinase inhibitor SB203580, the JNK inhibitor SP600125, and the NFκB activation inhibitor Bay11-7082 were purchased from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA).

PBMC isolation and cell culture

PBMCs were isolated from heparinized peripheral blood from healthy volunteers using Lymphoprep (Nycomed Pharma AS, Oslo, Norway) and further purified using a discontinuous 35/51% percoll gradient (Sigma, St Louis, MO) yielding monocytes of 93% purity, as described previously [13]. The remaining 7% cells of these PBMCs were microscopically identified as lymphocytes with Hema 3 stain. PBMCs were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Cells were incubated in ultra low attachment plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) or polypropylene tubes for LPS stimulation studies.

Immunoblotting

PBMCs treated with LPS were washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then lysed in RIPA buffer (1× PBS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitors: 20 μg/ml leupeptin, 20 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 200 μM sodium orthovanadate, and 20 mM sodium fluoride). Supernatants of cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, as described before [14]. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. Membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk, washed briefly, incubated with primary antibody at 4°C overnight, followed by incubating with corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoblot images were detected using chemiluminescence reagents and the Gene Gynome Imaging System (Syngene, Frederick, MD).

Flow cytometry

3×105 PBMCs were used for measurement of CD40 protein expression. Flow cytometry was performed with a FACSORT (Becton Dickinson, Miami, FL) using an Argon-ion laser (wavelength 488nm) [15]. The FACSORT was calibrated with Calibrite beads before each use, and 10,000 events were counted for all sample runs. PE-conjugated non-specific antibody of the same isotype as the receptor antibody was used as control to establish background fluorescence and non-specific antibody binding. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the cells stained with control antibody was subtracted from the MFI of cells stained with receptor antibody to provide a measure of receptor-specific MFI. Relative cell size and density/granularity were quantified by analyzing light-scatter properties using Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson), namely forward scatter for cell size and side scatter for density/granularity.

Real-time reverse transcriptase/polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

1×106 blood PBMCs were exposed to LPS. Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and then lysed with TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). Total RNA was isolated according to manufacturer-provided instructions. RNA (200ng) was reverse transcribed into cDNA. Quantitative PCR was performed using Platinum Quantitative PCR SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) and an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). mRNA levels of CD40 and IFNγ were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA. Relative amounts of CD40 or IFNγ and GAPDH mRNA were based on standard curves prepared by serial dilution of cDNA from human airway epithelial cells. The oligonucleotide primers and probes were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA).

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

5×105 PBMCs were treated with LPS. Supernatants were collected by centrifugation. Measurement of released IFNγ from PBMC culture with ELISA was conducted following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistics

Differences in CD40 expression or cytokine production were evaluated using nonparametric paired t tests with the overall α level set at 0.05. Data were presented as means ± SEMs.

Results and Discussion

LPS exposure increases CD40 expression on the monocytes of human PBMCs

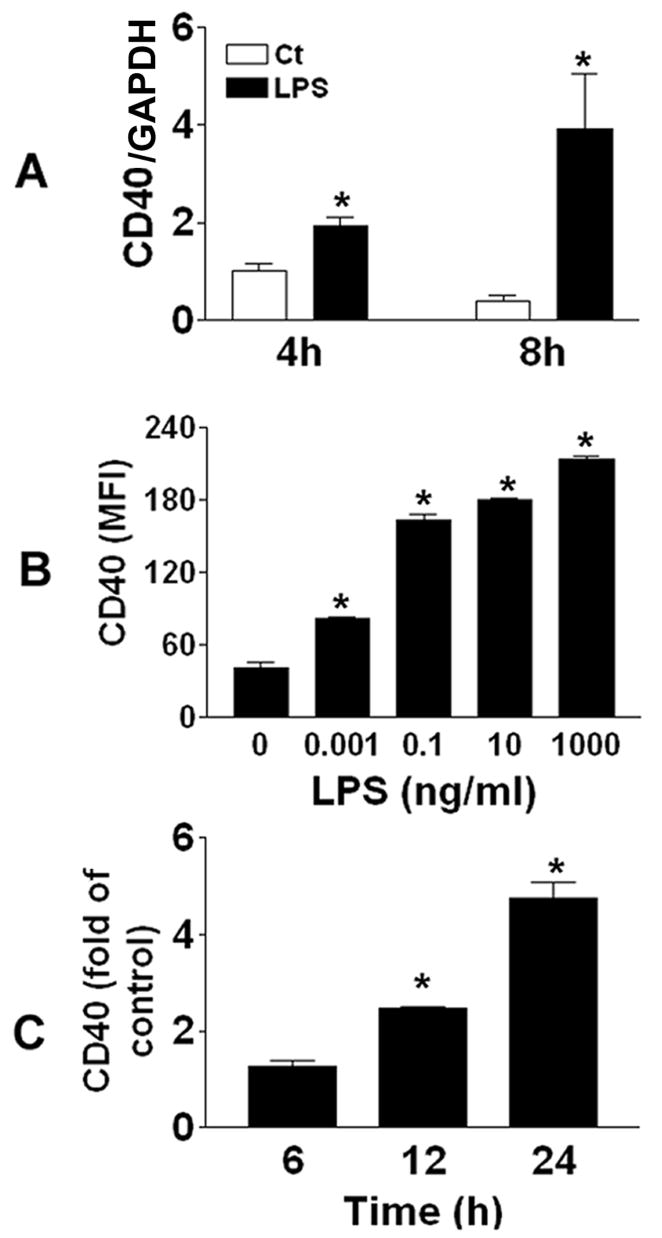

CD40 expression is observed in a wide range of cells, including macrophages and dendritic cells. In this present study, CD40 expression was determined on freshly isolated human PBMCs at both mRNA and cell surface protein levels. As shown in Fig.1A, PBMCs exposed to 1 ng/ml LPS developed increased CD40 mRNA expression at 4 h and a further increase at 8 h of exposure. Exposure of PBMCs to 0.001–1000 ng/ml LPS for 24 h induced a dose-dependent increase in CD40 cell surface protein expression (Fig.1B). Stimulation of PBMCs with 1 ng/ml LPS for 6, 12, and 24 h caused a time-dependent increase in CD40 protein expression that became significant at 12 h (Fig.1C). From flow analysis (gated on lymphocytes) we observed little increase of CD40 protein expression on the 7% residual lymphocytes. To confirm this with a larger number of cells, lymphocytes (99% purity) were collected through the same procedure for PBMC isolation and exposed to 1 ng/ml LPS for 24 h. It was found that LPS did not induce CD40 cell surface expression on these lymphocytes (data not shown). These data suggested that LPS-induced CD40 expression only occurred on the monocytes and not on the residual lymphocytes of PBMCs.

Fig 1. LPS exposure results in increase in CD40 expression on human monocytes.

A, Human PBMCs were treated with 1 ng/ml LPS for 4 and 8 h. Cells were then lysed with TRIZOL reagent. RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed before further analysis of CD40 mRNA expression using quantitative PCR. CD40 mRNA levels were normalized using the expression of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA. B, Human PBMCs were treated with 0.001–1000 ng/ml LPS for 24 h. C, PBMCs were incubated with 1 ng/ml LPS for 6, 12, and 24 h. CD40 protein expression was measured with flow cytometry using isotype and anti-CD40 antibodies, respectively, as described in Materials and Methods. *P<0.05, compared to control (Ct).

Activation of NFκB is required for LPS-induced CD40 expression on PBMCs

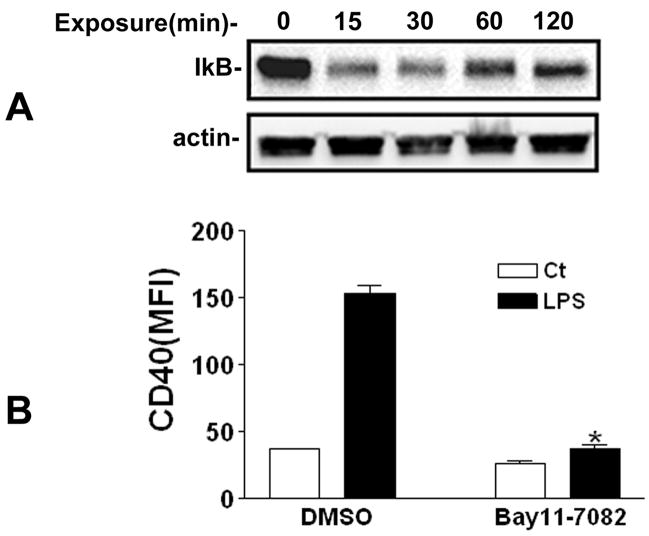

Because of the importance of NFκB activation in LPS-induced signaling [16, 17], the involvement of NFκB in LPS-induced CD40 gene transcription was investigated in this study. NFκB transcription factors are present in the cytoplasm in an inactive state, complexed with inhibitory IκB proteins, which cover the nuclear localization structures of NFκB. Phosphorylation of cytoplasmic IκBα at two conserved NH2-terminal serine residues (Ser32 and Ser36) and its subsequent proteosomal degradation by the 26S proteasome allows NFκB nuclear translocation and activation of NFκB-dependent transcriptional activity [18]. NFκB has been proposed as an important transcription factor in LPS-induced CD40 expression in murine macrophages and microglia [9]. Analysis of the CD40 promoter demonstrates that NFκB regulatory elements is conserved between the human and mouse CD40 promoters. Within the CD40 promoter, there are four NFκB sites that are designated as dκB, mκB, m2κB, and pκB [19]. To determine whether NFκB was activated by LPS stimulation in our system and to examine its involvement in LPS-induced CD40 expression, IκBα levels were determined in PBMCs exposed to LPS. As shown in Fig. 2A, LPS (1 ng/ml) induced a rapid time-dependent reduction of IκBα protein, indicative of NFκB activation. Recent studies have investigated the upstream signaling pathways responsible for LPS-induced NFκB activation. It was shown that LPS could induce NFκB activation through transforming growth factor β (TGFβ)-activated kinase (TAK1), which was a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK) family [16]. PI3K was also demonstrated to mediate LPS-induced NFκB activation through induction of p65 phosphorylation[20].

Fig 2. NFκB activation is required for LPS-induced CD40 expression.

A, PBMCs were treated with 1 ng/ml LPS for 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min. IκBα protein levels were measured with Western blotting using anti-IκBα antibody. B, PBMCs were pretreated with DMSO or 2 μM Bay11-7082 for 30 min prior to 1 ng/ml LPS stimulation for 24 h, respectively. CD40 expression (MFI) was measured with flow cytometry. * P<0.05, compared to vehicle (DMSO) LPS.

To investigate whether NFκB activation was involved in LPS-induced CD40 expression on human monocytes, we pretreated PBMCs with the potent inhibitor of NFκB activation Bay11-7082 [21] prior to LPS addition. PBMCs were pretreated with 2 μM Bay11-7082 for 30 min before addition of 1 ng/ml LPS. At this dose Bay11-7082 was not cytotoxic to PBMCs. As shown in Fig. 2B, Bay11-7082 strongly suppressed LPS-induced CD40 expression on monocytes at 24 h. Thus, NFκB activation was required for LPS-induced CD40 expression on the monocytes of human PBMCs as in murine macrophages and microglia [3, 9].

Signaling through CD40 is known to activate the NFκB pathway, and in this study we have demonstrated that CD40 expression is also regulated by NFκB. Taken together, the upregulation of CD40 expression might be regulated through a positive feedback mechanism using this CD40/NFκB activation pathway.

Involvement of JNK in LPS-induced CD40 expression

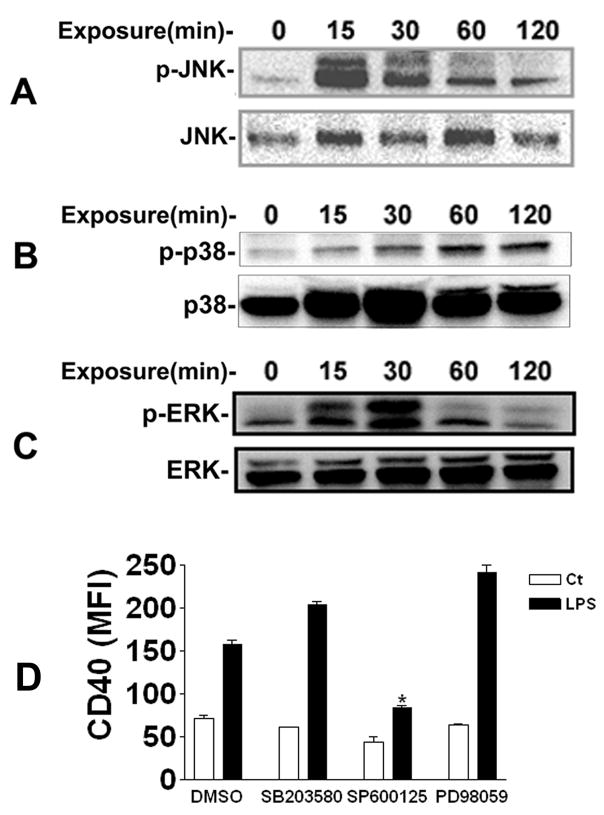

The MAPKs are generally expressed in all cell types. Three groups of MAPKs have been identified inmammals: the extracellular signal–regulated protein kinases (ERKs), the c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs), and the p38 stress-activated protein kinases. The ERK pathway appears mainly to respond to mitogens and growth factors that regulate cell proliferation and differentiation. The JNK and p38 pathways are predominantly activated by stress, such as osmotic changes and heat shock, but also by inflammatory cytokines. LPS is a potent activator of all three MAPKs [22]. Previous studies have demonstrated that MAPK-mediated LPS effects were cell type specific and depended on the surface molecules studied [23–25]. In this study, we examined the effect of LPS on activities of MAPKs and their involvement in CD40 expression on PBMCs. Activation of MAPKs occurs through phosphorylation of specific residues of these kinases. Thus, phosphorylation of MAPKs was measured using phospho-specific antibodies against JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), and ERK (Thr202/Tyr204), respectively. PBMCs were exposed to 1 ng/ml LPS for 15, 30, 60, and 120 min. As shown in Fig. 3, LPS stimulation resulted in a rapid increase in phosphorylation of JNK, p38, and ERK in PBMCs, reaching a maximum for JNK and ERK at 30 min whereas phosphorylation of p38 continued to increase throughout the period of observation.

Fig 3. JNK is partially involved in LPS-induced CD40 expression.

PBMCs were stimulated with 1 ng/ml LPS for 15–120 min. Cells were lysed with RIPA buffer. Supernatants of cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Phosphorylated JNK (A), p38 (B), and ERK (C) kinases were detected using phospho-specific antibodies. D, PBMCs were pretreated with DMSO (vehicle), 20 μM SB203580, 20 μM SP600125, or 20 μM PD98059 for 30 min, respectively, prior to 1 ng/ml LPS treatment for 24 h. CD40 expression was determined using flow cytometry. * P<0.05, compared to vehicle (DMSO) LPS. Data shown are representative of three separate experiments.

To determine whether activated MAPKs participated in LPS-induced CD40 expression on blood monocytes, we used selective kinase inhibitors, 20 μM PD98059, SP600125, and SB203580, which specifically inhibited ERK kinase, JNK, and p38 activities, respectively, to pretreat PBMCs for 30 min prior to LPS stimulation (1 ng/ml) for 24 h. It was found that only the JNK inhibitor SP600125 partially inhibited LPS-induced CD40 expression on the monocytes (Fig. 3D). Whether JNK modulates CD40 gene transcription through activation of transcription factors such as AP-1 in the CD40 promoter remains to be investigated.

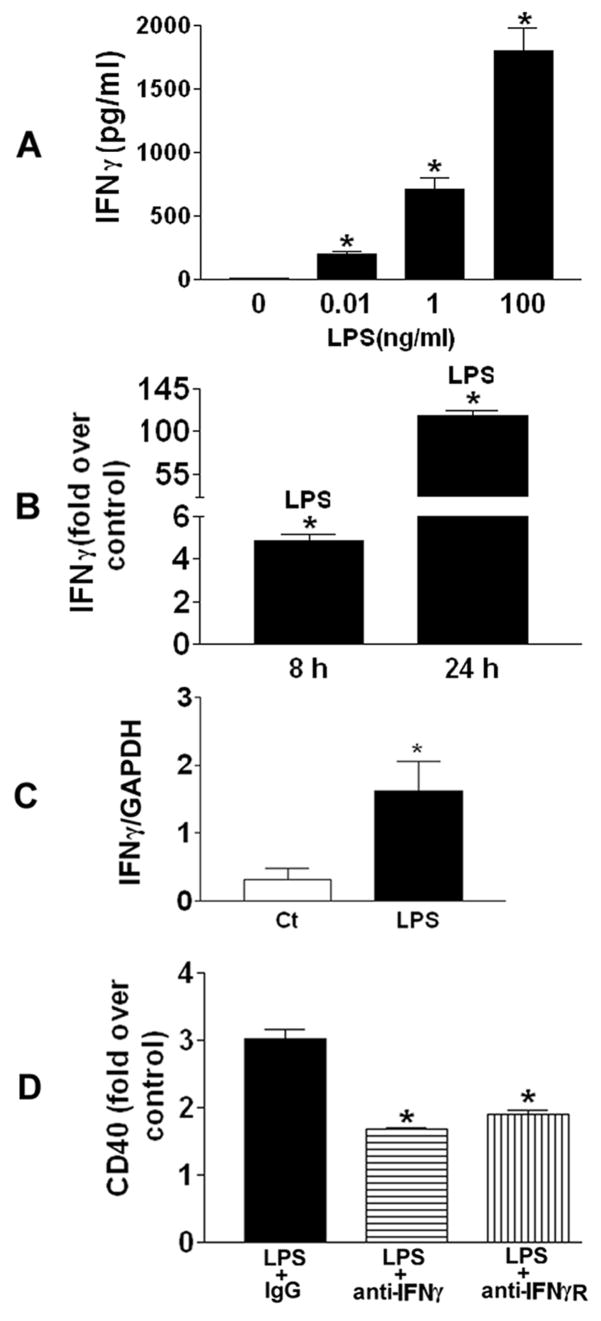

IFNγ released from the residual lymphocytes of PBMCs is partially involved in LPS-induced CD40 expression

Since 7% lymphocytes were presented in the PBMCs and lymphocytes were well-known for their production of IFNγ [26], a potent CD40 inducer [19], we next used ELISA to determine the levels of IFNγ, in the medium of PBMCs exposed to 0.01, 1, and 100 ng/ml LPS for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 4A, LPS stimulation induced dose-dependent increase in IFNγ protein levels in the medium of PBMCs. Exposure of PBMCs to 1 ng/ml LPS increased IFNγ protein production in a time-dependent fashion (Fig. 4B). In addition, IFNγ mRNA expression was also determined in PBMCs treated with 1 ng/ml LPS for 8 h (Fig. 4C), which showed that IFNγ mRNA levels were increased by LPS stimulation. Since freshly purified human monocytes do not produce detectable IFN activity when stimulated with LPS [27, 28], the IFNγ proteins detected in the culture medium must be secreted from the residual 7% lymphocytes. We confirmed this using a human monocytic cell line (THP-1) where no IFNγ production after LPS treatment was observed (data not shown).

Fig 4. LPS-induced IFNγ production is involved in CD40 expression.

A, PBMCs were treated with 0.01, 1, and 100 ng/ml LPS for 24 h, respectively. Supernatants of cell media were collected for measurement of IFNγ protein with ELISA. *P<0.05, compared to control (Ct). B, PBMCs were treated with 1 ng/ml LPS for 8 and 24 h, respectively. Supernatants of cell media were collected for measurement of IFNγ protein with ELISA. Increase in IFNγ protein release was expressed as fold over control. *P<0.05, compared to control (Ct) at the same time point. C, PBMCs were treated with 1 ng/ml LPS for 8 h prior to lysis with TRIZOL reagent. RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed before further analysis of IFNγ mRNA expression using quantitative PCR. D, PBMCs were pretreated with 20 μg/ml IgG (vehicle), anti-IFNγ, or anti-IFNγR for 2 h before treatment with 1 ng/ml LPS for 24 h, respectively. CD40 expression was determined and expressed as fold over control. *P<0.05, compared to vehicle LPS.

IFNγ is a dimerized soluble cytokine that is the only member of the type II class of IFN [29]. The major biological responses to IFNγ are mediated through the JAK/STAT pathway [30]. Seven mammalian STATs have been identified thus far, and STAT-1 is the major transcription factor in the IFNγ signal transduction pathway [30]. Binding of IFNγ to its receptor induces a series of events, which ultimately results in tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT-1, followed by homodimerization, nuclear translocation, and binding to GAS elements in the promoter regions of IFNγ-inducible genes. To ascertain the magnitude of the role played by IFNγ in LPS-induced CD40 expression, neutralizing antibodies against human IFNγ (anti-IFNγ) or IFNγ receptors (anti-IFNγR) were employed to pretreat PBMCs. To first characterize the specificities of these two neutralizing antibodies, PBMCs were pretreated with 20 μg/ml anti-IFNγ and anti-IFNγR, respectively, prior to addition of 500 pg/ml recombinant human IFNγ. It was shown that anti-IFNγ and anti-IFNγR significantly inhibited IFNγ-induced CD40 expression on PBMCs by 85% and 82%, respectively, at 24 h. Then, PBMCs were pre-incubated with 20 μg/ml IgG (vehicle), anti-IFNγ, or anti-IFNγ receptor (IFNγR) at 37ºC for 2 h prior to stimulation with 1 ng/ml LPS for 24 h. We observed that anti-IFNγ and anti-IFNγR inhibited LPS-induced CD40 expression by 44% and 37%, respectively (Fig. 4D). Therefore, these data indicated that IFNγ released from the lymphocytes of PBMCs was only partially responsible for LPS-induced CD40 expression. Additional studies have demonstrated that both NFκB and JNK were required for LPS-induced IFNγ production (data not shown). And the interaction between lymphocytes and monocytes in PBMC culture facilitated LPS-induced IFNγ production from the residual lymphocytes of PBMCs since the same number of isolated pure lymphocytes as in PBMCs produced less IFNγ after LPS stimulation.

In summary, LPS induces CD40 expression on human peripheral blood monocytes through activation of NFκB and JNK, and through IFNγ production by lymphocytes.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the technical assistance from Fernando Dimeo, Margaret Herbst, and Martha Almond. This work was supported by the NIH grant R01ES012706 and the United States Environmental Protection Agency Cooperative Agreement CR83346301.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.van Kooten C, Banchereau J. CD40-CD40 ligand. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:2–17. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banchereau J, Bazan F, Blanchard D, Briere F, Galizzi JP, van Kooten C, Liu YJ, Rousset F, Saeland S. The CD40 antigen and its ligand. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:881–922. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.004313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benveniste EN, Nguyen VT, Wesemann DR. Molecular regulation of CD40 gene expression in macrophages and microglia. Brain Behav Immun. 2004;18:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tone M, Tone Y, Babik JM, Lin CY, Waldmann H. The role of Sp1 and NF-kappa B in regulating CD40 gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8890–8897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109889200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park JH, Chang HS, Park CS, Jang AS, Park BL, Rhim TY, Uh ST, Kim YH, Chung IY, Shin HD. Association analysis of CD40 polymorphisms with asthma and the level of serum total IgE. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:775–782. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200609-1286OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schonbeck U, Libby P. The CD40/CD154 receptor/ligand dyad. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:4–43. doi: 10.1007/PL00000776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haase C, Markholst H. CD40 is required for development of islet inflammation in the RIP-CD154 transgenic mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1107:373–379. doi: 10.1196/annals.1381.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quandt K, Frech K, Karas H, Wingender E, Werner T. MatInd and MatInspector: new fast and versatile tools for detection of consensus matches in nucleotide sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4878–4884. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.23.4878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin H, Wilson CA, Lee SJ, Zhao X, Benveniste EN. LPS induces CD40 gene expression through the activation of NF-kappaB and STAT-1alpha in macrophages and microglia. Blood. 2005;106:3114–3122. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SJ, Qin H, Benveniste EN. Simvastatin inhibits IFN-gamma-induced CD40 gene expression by suppressing STAT-1alpha. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:436–447. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1206739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimaldi JC, Torres R, Kozak CA, Chang R, Clark EA, Howard M, Cockayne DA. Genomic structure and chromosomal mapping of the murine CD40 gene. J Immunol. 1992;149:3921–3926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becker S, Soukup J. Coarse(PM(2.5–10)), fine(PM(2.5)), and ultrafine air pollution particles induce/increase immune costimulatory receptors on human blood-derived monocytes but not on alveolar macrophages. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2003;66:847–859. doi: 10.1080/15287390306381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soukup JM, Becker S. Role of monocytes and eosinophils in human respiratory syncytial virus infection in vitro. Clin Immunol. 2003;107:178–185. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu W, Silbajoris RA, Whang YE, Graves LM, Bromberg PA, Samet JM. p38 and EGF receptor kinase-mediated activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway is required for Zn2+-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L883–889. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00197.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alexis NE, Lay JC, Almond M, Bromberg PA, Patel DD, Peden DB. Acute LPS inhalation in healthy volunteers induces dendritic cell maturation in vivo. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawai T, Akira S. Signaling to NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptors. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:460–469. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang T, Zhang X, Li JJ. The role of NF-kappaB in the regulation of cell stress responses. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:1509–1520. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(02)00058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen VT, Benveniste EN. Critical role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and NF-kappa B in interferon-gamma -induced CD40 expression in microglia/macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13796–13803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111906200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guha M, Mackman N. LPS induction of gene expression in human monocytes. Cell Signal. 2001;13:85–94. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(00)00149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shanmugam N, Kim YS, Lanting L, Natarajan R. Regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 expression in monocytes by ligation of the receptor for advanced glycation end products. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34834–34844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302828200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sweet MJ, Hume DA. Endotoxin signal transduction in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:8–26. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakahara T, Uchi H, Urabe K, Chen Q, Furue M, Moroi Y. Role of c-Jun N-terminal kinase on lipopolysaccharide induced maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1701–1709. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim W, Gee K, Mishra S, Kumar A. Regulation of B7.1 costimulatory molecule is mediated by the IFN regulatory factor-7 through the activation of JNK in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocytic cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:5690–5700. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gee K, Kozlowski M, Kumar A. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces functionally active hyaluronan-adhesive CD44 by activating sialidase through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocytic cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37275–37287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302309200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bogdan C, Schleicher U. Production of interferon-gamma by myeloid cells--fact or fancy? Trends Immunol. 2006;27:282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerrard TL, Dyer DR, Enterline JC, Zoon KC. Products of stimulated monocytes enhance the activity of interferon-gamma. J Interferon Res. 1989;9:115–124. doi: 10.1089/jir.1989.9.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayes MP, Enterline JC, Gerrard TL, Zoon KC. Regulation of interferon production by human monocytes: requirements for priming for lipopolysaccharide-induced production. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;50:176–181. doi: 10.1002/jlb.50.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray PW, Goeddel DV. Structure of the human immune interferon gene. Nature. 1982;298:859–863. doi: 10.1038/298859a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shuai K, Liu B. Regulation of JAK-STAT signalling in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:900–911. doi: 10.1038/nri1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]