Abstract

Primary community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) endocarditis has rarely been reported in healthy individuals without risk factors, such as skin and soft tissue infections, and intravenous drug abuse. We describe a case of infective endocarditis by CA-MRSA (ST72-PVL negative-SCCmec IVA) in previously healthy individuals with no underlying medical condition and CA-MRSA colonization in the family.

Keywords: Endocarditis, colonization in family, community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

INTRODUCTION

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections have been reported among healthy persons who have no prior contact with healthcare system, and these cases have primarily been associated with skin and soft-tissue infections and severe necrotizing pneumonia, particularly in the past decade.1,2 Although increased incidence of community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) endocarditis has been reported recently, a large proportion of cases had a documented history of skin lesion,3 including furunculosis, cellulitis and/or intravenous drug use,4,5 and CA-MRSA endocarditis among individuals with no underlying medical condition has rarely been reported. Herein, we describe a case of primary infective endocarditis caused by CA-MRSA in previously healthy person and CA-MRSA colonization in the family.

CASE REPORT

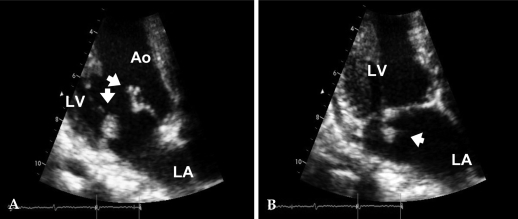

A 39-year-old female was admitted with complaints of intermittent high fever, chill, and fatigue of 2 weeks duration. She had no medical problems including intravenous drug abuse, underlying heart disease, dental problem, or previous exposure to healthcare personnel or a hospital environment. She was living with her parents, and her nutritional status was good. On admission, she appeared acutely ill. Her body temperature was 39.2℃, her blood pressure was 100/70 mmHg, her pulse rate was 96/min, and her respiratory rate was 24/min. Physical examination was negative for the following: conjunctival hemorrhage, petechiae, tender nodule, and Janeway lesion on the hands. A grade II/VI systolic murmur was detected over the cardiac apex. There was neither evidence of skin infection nor pneumonia. Her initial WBC count was 19,460/mm3 with neutrophilia (90.8%). Urinalysis showed neither proteinuria nor hematuria. We conducted a transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) on hospital day 2. The TTE showed multiple irregular-shaped mobile oscillating echogenic masses on the tips of both anterior and posterior mitral leaflets (1.63 cm and 0.7 cm, respectively), with trivial mitral regurgitation and normal LV function (Ejection Fraction = 64%, Fig. 1). Empirical antibiotic treatment with surgery, a follow-up TTE was negative for vegetation, and she was transferred to the Department of Rehabilitation. She was discharged on hospital day 121, and she had no disease recurrence at 1 year follow up.

Fig. 1.

Transthoracic echocardiography shows vegetations (arrows) on both mitral leaflets; (A) Diastole. (B) Systole. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; Ao, aorta.

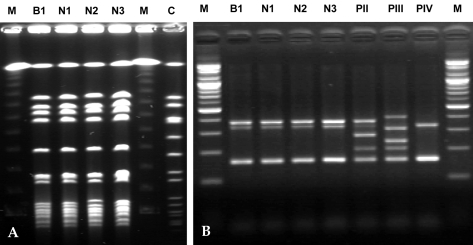

MRSA surveillance cultures were obtained from nasal swab of the patient and her family (parents, 3 sisters, a brother-in-law, and a brother; all had no previous medical history in the last several years). Among the 6 family members investigated, 2 (the father and the brother-in-law) were positive for MRSA surveillance cultures with the antimicrobial susceptibility similar to that of the patient. We performed multiplex PCR for the detection of the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) gene and SCCmec typing,6 multilocus sequence typing (MLST), and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). MRSA isolates from 2 family members showed a PFGE pattern similar to that of the patient. All MRSA isolates from the patient (blood and nasal surveillance) and 2 family members were PVL-negative SCCmec IVA type; the MLST allelic profile revealed ST72; 1-4-1-8-4-4-3 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Molecular profiling (A) Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis shows clonal relationship between 4 community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates. M, Marker; B1, Blood isolate of the patient; N1, Nasal isolate of the patient; N2, Nasal isolate of the patient's father; N3, Nasal isolate of the patient's brother-in-law; C, Control. (B) All 4 community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates were Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL)-negative SCCmec IVA clone. M, Marker; B1, Blood isolate of the patient; N1, Nasal isolate of the patient; N2, Nasal isolate of the patient's father; N3, Nasal isolate of the patient's brother-in-law; PII, SCCmec II positive sample; PIII, SCCmec III positive sample; PIV, SCCmec IV positive sample.

DISCUSSION

Emergence of MRSA as a cause of infection in the community is a significant concern.1,2 More recently, infective endocarditis (IE) due to the involvement of CA-MRSA has been described.5,7 In these studies, most of the patients did not have traditional risk factors for the acquisition of IE, e.g., structural heart disease or prior rheumatic fever.7 In the majority of cases reported, CA-MRSA endocardial infection developed in intravenous drug users and after development of furunculosis and abscesses, osteomyelitis, or pneumonia.3-5,7 Although CA-MRSA IE has increased dramatically in the USA, especially associated with injection drug use,5,8 CA-MRSA endocarditis among individuals with no underlying medical condition has rarely been reported. To the best of our knowledge, only a single case of CA-MRSA native valve endocarditis among non-intravenous drug users with no preceding infections has so far been reported.9

In Korea, MRSA accounts for more than 60% of S. aureus in hospital settings, however, CA-MRSA infections are not common and have rarely been reported.10 A survey of CA-MRSA in Korea revealed that skin and soft tissue infections or ear infections were common, and that a new clone of CA-MRSA (ST72-SCCmec IVA) without the PVL gene was the most common form among pathogens and colonizers, differing in several characteristics from those of other countries.11,12 In the present case, the causative CA-MRSA was a PVL-negative ST72-MRSA-IVA clone, the most common form in Korea.

CA-MRSA tends to be more susceptible to non-beta-lactam antibiotics than hospital-acquired MRSA, nevertheless, the antibiotic management of CA-MRSA IE should follow current international guidelines for infective endocarditis.7 We treated the patient with vancomycin for 6 weeks according to the guidelines.

Colonization is a strong risk factor for subsequent infection, although most persons colonized with the organism do not develop clinical disease,13 and infections caused by S. aureus are generally believed to follow colonization of the skin or nares of the host.2,13,14 PFGE revealed that the present case of MRSA endocarditis was of endogenous origin, since it originated from colonies in the nasal mucosa and we were able to document clonal CA-MRSA colonization in the family. For infection control measures and empirical antibiotic treatment, prevalence and risk factor for CA-MRSA colonization and infection should be investigated in Korea.

We suggest that CA-MRSA should be considered a possible etiologic agent of infective endocarditis in a healthy individual with no classical risk factors for the acquisition of MRSA, no past history of skin and soft tissue infections, or intravenous drug abuse. It may be associated with familial CA-MRSA colonization.

References

- 1.Crum NF. The emergence of severe, community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;37:651–656. doi: 10.1080/00365540510033636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zetola N, Francis JS, Nuermberger EL, Bishai WR. Community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an emerging threat. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:275–286. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahrain M, Vasiliades M, Wolff M, Younus F. Five cases of bacterial endocarditis after furunculosis and the ongoing saga of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38:702–707. doi: 10.1080/00365540500447150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsigrelis C, Armstrong MD, Vlahakis NE, Batsis JA, Baddour LM. Infective endocarditis due to community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in injection drug users may be associated with Panton-Valentine leukocidin-negative strains. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39:299–302. doi: 10.1080/00365540601003803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fowler VG, Jr, Miro JM, Hoen B, Cabell CH, Abrutyn E, Rubinstein E, et al. Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis: a consequence of medical progress. JAMA. 2005;293:3012–3021. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.24.3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliveira DC, de Lencastre H. Multiplex PCR strategy for rapid identification of structural types and variants of the mec element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2155–2161. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.7.2155-2161.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Millar BC, Prendergast BD, Moore JE. Community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA): an emerging pathogen in infective endocarditis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:1–7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ako J, Ikari Y, Hatori M, Hara K, Ouchi Y. Changing spectrum of infective endocarditis: review of 194 episodes over 20 years. Circ J. 2003;67:3–7. doi: 10.1253/circj.67.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin JC, Wu JS, Chang FY. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis with septic embolism of popliteal artery: a case report. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2000;33:57–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SY, Kim JY, Lee HS, Park C, Park YS, Seo YH, et al. A case of acute pyelonephritis caused by community acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Chemother. 2007;39:100–103. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim ES, Song JS, Lee HJ, Choe PG, Park KH, Cho JH, et al. A survey of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Korea. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:1108–1114. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park C, Lee DG, Kim SW, Choi SM, Park SH, Chun HS, et al. Predominance of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying staphylococcal chromosome cassette mec type IVA in South Korea. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:4021–4026. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01147-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Eiff C, Becker K, Machka K, Stammer H, Peters G. Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:11–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wertheim HF, Vos MC, Ott A, van Belkum A, Voss A, Kluytmans JA, et al. Risk and outcome of nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in nasal carriers versus non-carriers. Lancet. 2004;364:703–705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16897-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]