Abstract

Derivation of insulin producing cells (IPCs) from embryonic stem (ES) cells provides a potentially innovative form of treatment for type 1 diabetes. Here, we discuss the current state of the art, unique challenges and future directions on generating IPCs.

Introduction

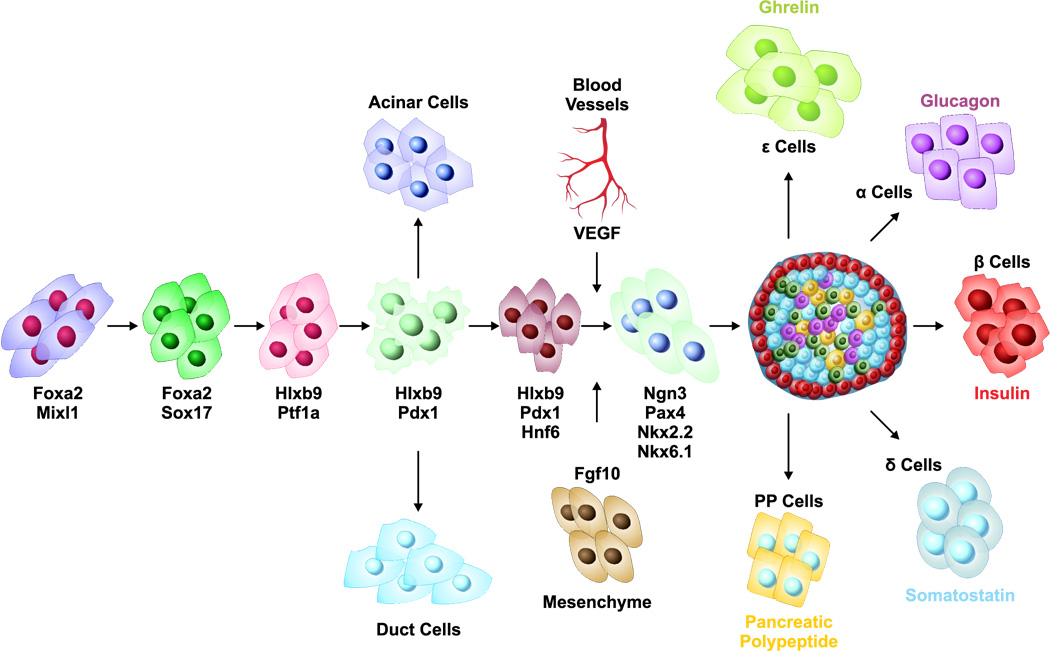

Type 1 diabetes is caused by the autoimmune destruction of insulin producing β cells within the pancreatic islets. Islet transplantation is now well established and has allowed weaning some patients off of insulin treatment. However two major problems have prevented a widespread use of this promising treatment modality. First, each patient requires more than 600 islet equivalents/kg body weight per transplantation, thereby necessitating at least two deceased organ donors. However, at present the chronic shortage of the organ donors is the major limiting factor. Second, islet transplants require lifelong immunosuppressive regimens to control rejection. These regimens are not only expensive but generally reduce the patient’s quality of life due to drug-induced side effects. Hence there is an urgent and compelling need to develop novel alternative therapies for the treatment of type 1 diabetes. An additional problem is the reemerging autoreactive T cells capable of destroying not only the patient’s remaining islets and blocking β-cell regeneration, but also the newly transplanted donor islets thereby ultimately leading to chronic graft rejection. If additional renewable sources of IPCs can be generated, islet transplantation could significantly be improved. In this regard, ES cells and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells offer a potentially novel approach for their lineage commitment into IPCs (Chan et al., 2007;Raikwar et al., 2006;Hanna et al., 2007;Nakagawa et al., 2008;Okita et al., 2007; Park et al., 2008; Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006; Yu et al., 2007; Wernig et al., 2007). ES cells which are derived from the inner cell mass of the early developing embryo are pluripotent and are capable of undergoing multi-lineage differentiation into highly specialized cells representing all three germinal layers (Evans and Kaufman, 1981; Martin, 1981; Thomson et al., 1998). Due to their unlimited proliferation and differentiation potential, ES cells and iPS cells represent an alternate novel source for targeted therapies and regenerative medicine especially for type 1 diabetes. However, earlier studies (Lumelsky et al., 2001) have shown inherent difficulties in establishing a consistent protocol for β-cell derivation from ES cells. The development of the pancreas and especially pancreatic β cells is governed by major transcription factors and signaling pathways (Figure 1). The protocols for the efficient differentiation of ES cells into IPCs are expected to recapitulate the in vivo development of pancreatic β cells.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of pancreatic development: Pancreatic development and specification of insulin producing β cells is governed by a cascade of transcription factors and signaling pathways.

ES cell Differentiation into IPCs

Currently, there are two main strategies for the differentiation of ES cells into IPCs: i) embryoid body (EB) formation and ii) definitive endoderm (DE) formation. These approaches will be discussed below.

Embryoid Body Formation

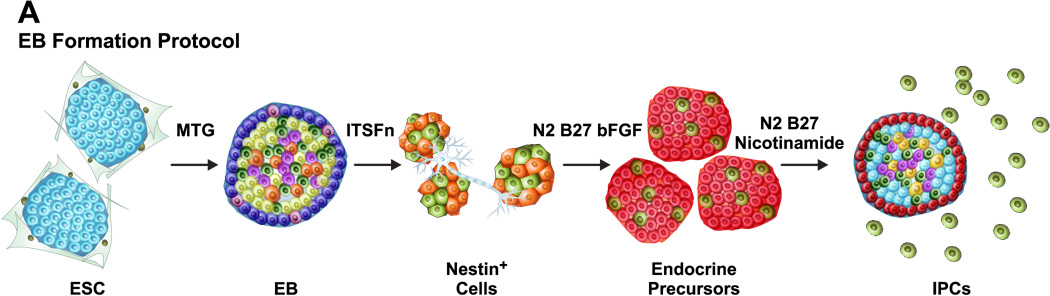

The first strategy relies upon an initial EB formation. EB represents a spherical arrangement of ES cells destined to differentiate into precursors of all the three germinal lineages including ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm. Sequential treatment of EBs with a cocktail of growth factors enforces a lineage commitment pathway that initially gives rise to Nestin+ cells, which subsequently differentiate into endocrine precursors and ultimately into IPCs (Figure 2A). Nestin, a neurofilament protein marker of neuronal progenitors is expressed within the pancreas primarily in the neurons, mesenchymal cells and vascular endothelium (Cattaneo and McKay, 1990; Humphrey et al., 2003; Klein et al., 2003; Lardon et al., 2002; Lendahl et al., 1990). Nestin has also been proposed to be a marker of pancreatic mesenchymal cells that can serve as endocrine progenitors (Zulewski et al., 2001). In these studies, Nestin+ cells were identified within the adult rat islets and shown to be capable of differentiation into IPCs in vitro. Treutelaar and colleagues (Treutelaar et al., 2003) have suggested that the Nestin-lineage cells contribute to the pancreatic microvasculature but not the endocrine cells of the pancreatic islets. Surprisingly, Maria-Engler and colleagues (Maria-Engler et al., 2004) have analyzed the expression of Nestin in short and long term human islet derived cultures using confocal microscopy and confirmed that, at least in vitro, Nestin+ cells may undergo the early stages of differentiation to an islet cell phenotype. These studies have further suggested that long term cultures of Nestin+ human islet cells may be considered as a potential source of precursor cells to generate fully differentiated functional β cells. However, recent lineage tracing studies using a Nestin promoter-Cre transgene have contradicted the idea that Nestin+ cells could function as endocrine progenitors (Delacour et al., 2004;Esni et al., 2004). Thus, further studies are needed to resolve the critical issue whether or not Nestin+ cells represent true pancreatic endocrine precursors. According to the current paradigm, many transcription factors regulating pancreatic β cell development and insulin gene expression are also required for the neuronal differentiation (Rolletschek et al., 2006). In a recent study, Boyd et al. (Boyd et al., 2008) compared three different protocols to generate IPCs using mouse ES cells using the EB formation approach. Their studies indicate that IPCs generated using the Blyszczuk protocol (bypassing the ITSFn and bFGF treatments) exhibited superior C-peptide expression and longer but limited functional normoglycemic response in diabetic mice as compared to the Lumelsky’s (involves sequential ITSFn and bFGF treatments) and Hori’s protocols (similar to Lumelsky’s protocol but involves treatment of differentiating IPCs with PI3 Kinase inhibitor LY294002 without B27 supplement).

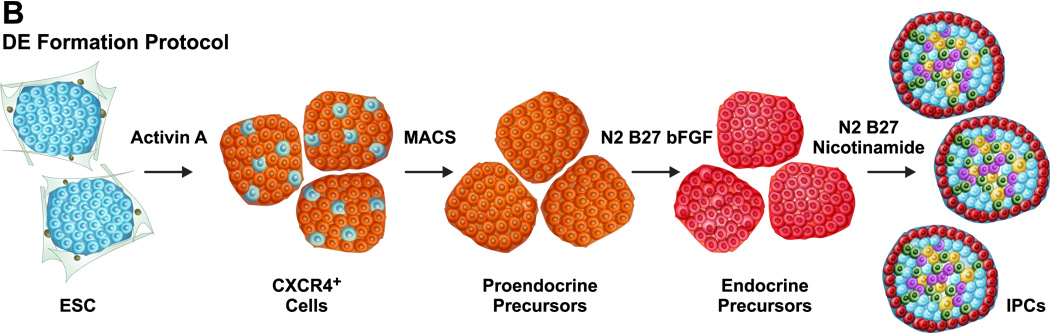

Figure 2.

Generation of ES cell-derived IPCs: (A) Embryoid body formation: Undifferentiated ES cells are initially converted into EBs and subsequently treated with a cocktail of growth factors to yield IPCs. (B) Definitive endoderm formation: Undifferentiated ES cells are treated with Activin A to generate DE cells which are characterized by cell surface CXCR4 expression. Selective enrichment of CXCR4+ DE cells followed by treatment with growth factors gives rise to IPCs.

One of the major controversial issues regarding the ES cells differentiation into IPCs using EB formation is whether the detected insulin is a result of selective uptake from the media or is a result of de novo synthesis (Hansson et al., 2004;Rajagopal et al., 2003;Sipione et al., 2004). This is due to the fact that the supplements used in the differentiation media especially ITSFn, N2 and B27 contain a high insulin content leading to an overall insulin concentration in the media exceeding the circulating levels by more than 1000 fold, thereby making it rather difficult to estimate de novo insulin synthesis by the newly derived IPCs. Clearly, this issue could be resolved by performing C-peptide staining which is highly specific for the precursor form of insulin. Since only the mature form of insulin is added to the medium, immunoreactivity for C-peptide or proinsulin would indicate that the precursor insulin is synthesized de novo. Thus, with any ES cell differentiation protocol, C-peptide staining appears more accurate in examining synthesis of insulin. It would also be important to simultaneously perform C-peptide ELISA in parallel with the insulin ELISA to rule out such a possibility.

The potential of ES cell-derived IPCs using the EB approach to correct diabetic phenotype in streptozotocin induced diabetic mice has been reported with limited success. Soria et al. employed a cell trapping strategy in which the neomycin resistance gene placed under the transcriptional regulation of the insulin promoter was exploited to select ES cells-derived IPCs (Soria et al., 2000). However, the efficiency of generating IPCs using this approach was extremely low. Although the transplantation of the IPCs in streptozotocin treated mice led to transient correction of blood glucose levels these studies failed to demonstrate that the surgical removal of the kidney bearing the graft would reverse the beneficial effects mediated by the IPCs and render the mice hyperglycemic. Transplantation studies by Blyszczuk et al. indicate a transient correction of blood glucose levels (Blyszczuk et al., 2003). In these studies 1–2 million cells were transplanted either under the kidney capsule or into the spleen. However, it is not clear as to what percentage of the total cells were actually IPCs, especially because some of the transplanted mice developed tumors in the kidney and the spleen. Thus, clearly there is evidence that the IPCs were in fact a heterogeneous mixture of undifferentiated ES cells, IPCs and differentiated cells from other lineages. Similar results have also been reported by other investigators (Hori et al., 2002;Sipione et al., 2004). Fujikawa et al. have further confirmed that the transplantation of ES cells-derived IPCs leads to teratoma formation in the kidneys (Fujikawa et al., 2005). Thus, at present, teratoma formation is one of the major concerns regarding the potential clinical utility of ES cells-derived IPCs using the EB formation protocols.

Definitive Endoderm Approach

More recently, differentiation of ES cells into IPCs has been achieved by bypassing the EB formation and selectively generating the definitive endoderm (DE) (Figure 2B). In this approach, ES cells are treated with Activin A, which together with Nodal, belongs to the TGF-β superfamily that activates Smad2-mediated intracellular signaling. Activin A treatment of ES cells leads to the mRNA expression of Foxa2 and Mixl1 by day 5, Sox17 by day 6 and Pdx1 by day 7 (Kubo et al., 2004). Baetge and colleagues have recently demonstrated that Activin A treatment of human ES cells leads to the generation of DE and using a multistep protocol these cells give rise to IPCs (D'Amour et al., 2006;McLean et al., 2007). In their studies, Activin A treatment of undifferentiated human ES cells in the serum free medium promotes the induction of DE formation. Subsequently a combination of FGF and RA signaling as well as inhibition of SHH signaling leads to a pancreatic fate of the DE cells. Further treatment of the differentiating cells with the Notch signaling inhibitor and a cocktail of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), insulin like growth factor I (IGF1) and glucagon-like peptide 1 analog Exendin-4 led to the generation of IPCs. However, the frequency of IPCs generation using this protocol was very low. Moreover, the small fraction of the IPCs that were generated failed to process proinsulin well and were not glucose responsive.

In their latest studies, the same group has reported a much more efficient strategy to differentiate human ES cells into IPCs that are functional in a xenotransplant diabetic model (Kroon et al., 2008). In their modified approach, these investigators capitalized on the fact that fetal human pancreatic tissues at either 6–9 weeks or 14–20 weeks have been shown to develop into glucose-responsive islets that correct hyperglycemia in diabetic mice post transplantation (Castaing et al., 2001;Castaing et al., 2005;Hayek and Beattie, 1997;Tuch et al., 1989). Their new protocol consists of four stages instead of five and requires only 12 days of differentiation. During the first stage, treatment of human ES cells with Activin A (100 ng/ml) and Wnt3a (25 ng/ml) followed by Activin A (100 ng/ml) treatment alone leads to DE formation via an intermediate mesendoderm formation. In the next stage, cyclopamine treatment is eliminated and KGF (25–50 ng/ml) is substituted for FGF10 (4–6 days). This is followed by treatment of differentiating cells with B27, KAAD-cyclopamine (0.25 µM), all-trans retinoic acid (2 µM) and Noggin (50ng/ml) instead of FGF10 (3 days). This combination of SHH and BMP signaling inhibitors and the presence of RA leads to the development of posterior foregut with the expression of Pdx1, Hnf6, Prox1 and Sox9. In the final step, these cells are cultured in the absence of all the factors except B27 and finally give rise to pancreatic endoderm and endocrine precursors which express Nkx6.1, Ptf1a, Ngn3 and Nkx2.2 with many of these differentiated cells coexpressing either glucagon and insulin or insulin and somatostatin. These differentiated endocrine precursor cells were implanted into either the epididymal fat pads, subcutaneous tissue or under the kidney capsule of immunodeficient male SCID-beige mice and allowed to mature in vivo for several months. Following in vivo development, the functionality of the transplanted human ES cell derived IPCs to rescue the diabetic phenotype in the SCID-beige mice was tested by streptozotocin treatment which selectively destroys mouse but not the human β cells. Successful engraftment was observed in 83% mice for subcutaneous implants, 94% for epididymal fat pad implants and 100% for kidney capsule implants. To further verify that the human ES cell derived IPCs were indeed solely responsible for rescuing the diabetic phenotype and to rule out regeneration of endogenous β cells, the grafts were surgically removed 100 days post streptozotocin treatment. This led to an immediate hyperglycemia thereby unambiguously demonstrating that indeed the human ES cell derived IPCs successfully prevented streptozotocin induced diabetes. This exciting study represents one of the first successful demonstration of the human ES cell derived IPCs to correct the diabetic phenotype and therefore raises great optimism regarding the potential clinical utility of human ES cell based regenerative therapy for millions of diabetic patients world wide.

Novel approaches for the generation of IPCs

There are several inherent limitations in the currently available ES cell differentiation protocols. Unlike differentiation of ES cells into beating cardiomyocytes which can be visually imaged or into hematopoietic stem cells which can be identified by flow cytometry, there are remarkable challenges associated with the identification and monitoring of ES cells undergoing differentiation into IPCs. This major limitation is further worsened by the fact that currently available protocols for the differentiation of ES cells into IPCs are labor intensive, prohibitively expensive and fairly time consuming. Despite significant improvements in the currently available ES cell differentiation protocols, the final yield of IPCs are still very low (≤ 1% of the final heterogeneous cell population). Thus, for ES cells to become a potential source of IPCs that can be used clinically, significantly improved and novel protocols need to be developed. In addition, the amount of insulin produced by each IPC compared to that produced by a single islet appears to be less than a tenth based on our estimates. This major challenge could potentially be overcome by establishing several different approaches.

a) Generation of stable ES cell lines expressing pancreatic β cell specific transcription factors

The efficiency of ES cell differentiation into IPCs can be significantly enhanced by the generation of stable ES cells lines expressing key transcription factors involved in the development of pancreatic β cells. Blyszczuk and colleagues have reported on the development of R1 ES cells constitutively expressing Pdx1 and Pax4 (Blyszczuk et al., 2003). They found that constitutive Pax4 expression in combination with histotypic cultivation led to the formation of islet like structures. A concern regarding their protocol is the use of the CMV promoter for the overexpression of Pdx1 and Pax4 and use of second plasmid expressing antibiotic resistance marker for generating stable ES cell line. The CMV promoter undergoes rapid silencing in the undifferentiated ES cells while the PGK promoter remains constitutively active (Hong et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2007; Liew et al., 2007). Thus, while it is possible to select G418 resistant colonies using this approach, it is extremely difficult to achieve constitutive expression of either Pdx1 or Pax4. It is further clear from their RT-PCR studies that all of their undifferentiated wild type ES cells, Pdx1+ and Pax4+ stable ES cell lines expressed Pdx1. This controversial data self-contradicts their claim of having generated a stable Pdx1 expressing ES cell line. An approach worth exploring would be to express pancreatic β cell specific transcription factors in undifferentiated ES cells using mammalian promoters that are not subject to silencing. Also it is equally important to include in the expression vector the antibiotic selection marker that is driven by a different promoter which will be transcriptionally active in the undifferentiated ES cells.

However, due to possible cytotoxicity of Pdx1 on overexpression, establishing stable Pdx1 ES cell lines is a major challenge. This problem has been overcome by developing doxycycline inducible Pdx1 ES cell line (Miyazaki et al., 2004). More recently, Vincent and colleagues have developed doxycycline-inducible mouse ES cells to achieve inducible expression of various pancreatic transcription factors including Hnf4α, Hnf6, Nkx2.2, Nkx6.1, Pax4, Pdx1 and Ptf1a (Vincent et al., 2006). Each of these cell lines showed an inducible transgene expression in the presence of doxycycline as well as maintained pluripotency in in vivo studies. These new ES cells lines will prove invaluable not only in exploring gene regulatory networks in pancreatic development but will also enable the generation of greater numbers of IPCs. In yet another study, Lavon and colleagues have generated Pdx1 and Foxa2 overexpressing human ES cells lines (Lavon et al., 2006). In these studies the expression of Foxa2 was controlled by the PGK promoter while that of Pdx1 was controlled by the β actin promoter. Although these Foxa2 and Pdx1 overexpressing ES cells were able to form EBs, they failed to generate IPCs and were differentiated mainly toward exocrine cells.

Two independent groups have reported the development of doxycycline inducible Ngn3 expressing mouse ES cells lines (Serafimidis et al., 2008; Treff et al., 2006). Doxycycline treatment resulted in Ngn3 expression, which ultimately led to upregulation of NeuroD, Pax4, Nkx2.2, IA1 and Dll1 which are involved in the pancreatic β cell development. Further these Ngn3 expressing cells gave rise to glucose responsive IPCs although at a lower frequency. These results suggest that Ngn3 expression alone which lies downstream of the Pdx1 signaling may not be enough to efficiently differentiate ES cells into IPCs. Differentiation of ES cells co-expressing Ngn3 and Pdx1 might enhance the generation of IPCs. However, it is possible that this approach might not work since it has been shown earlier that constitutive, high-level Pdx1 expression might actually be toxic to the ES cells (Miyazaki et al., 2004). More recently, it has now been reported that the human and mice Ngn3+ islet progenitor cells express two cell surface markers, CD133 (prominin-1) and CD49F (α 6 integrin) that permit FACS based enrichment of hormone− Ngn3+ cells from differentiated insulin+ or glucagon+ islet cells lacking Ngn3 (Sugiyama et al., 2007). Further it was also shown that the Ngn3+ cells also expressed low levels of CD24 (a glycophosphatidylinositol-anchored cell surface protein) which is also found on brain derived neural cells. Approximately 8% of CD133+ CD49Flow cells expressed Ngn3 and when subjected to in vitro differentiation following co-culture either with mitomycin C-treated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or with PA6 mouse stromal cells, they gave rise to distinct insulin+ and glucagon+ cells within 5 days. These results imply that CD133 and CD49f which are respectively expressed on the apical and the basolateral surfaces of the Ngn3+ islet progenitors have the potential to be used for enriching the Ngn3+ cells from the ES cells undergoing differentiation into IPCs, thereby significantly maximizing the generation of IPCs.

b) Generation of pancreatic transcription factor knockout mice and in vivo transplantation models

Development of single knockouts of various pancreatic transcription factors has provided important insights regarding pancreatic development. More recently double knockouts have been generated and have offered novel insights into synergistic or antagonistic molecular mechanisms mediated by multiple transcription factors (Chao et al., 2007). There is an urgent need to initiate research efforts to identify novel molecular signals, signaling pathway components and transcription factors that precisely regulate endoderm specification and pancreatic fate determination. It would be very crucial to identify various molecular markers defining multiple stages of pancreatic development including cell-specific markers of pancreatic endocrine stem/progenitor cells. Thus far, the ES cell-derived IPCs have been studied in isolation whereas pancreatic β cells exhibit a highly organized architecture wherein they co-exist with α, δ, ε and PP cells within the islets of Langerhans. Hence there is a need to investigate the spatiotemporal relationship and in vivo cell-cell interactions between pancreatic β cells and the α, δ, ε and PP cells. These studies have the potential to elucidate the novel dynamic relationships among various types of cells within the pancreatic islets which will ultimately lead to the development of the next generation of ES cell differentiation protocols for the efficient generation of IPCs. Once this has been successfully achieved, it would be necessary to examine the crucial role of angiogenesis in facilitating the in vivo engraftment of ES cell-derived IPCs This is clearly one of the most promising avenues of research especially because one of the major caveats of current islet transplantation is poor graft survival due to lack of neovasculature development which is ultimately responsible for massive apoptosis of transplanted islets. Finally, it would suffice to mention the vital importance of developing a noninvasive real-time molecular imaging modality to monitor the fate of the ES cell-derived IPCs in vivo in post transplant recipients. Finally, the interaction of the immune system with these new ES derivatives requires further study.

c) In vivo differentiation of partially differentiated ES cells

The next approach to maximize the generation of IPCs using ES cells involves a combination of in vitro partial differentiation of ES cells followed by in vivo differentiation and maturation of the precursors into IPCs post transplantation in streptozotocin induced diabetic mice. In this case there could be two possible scenarios. First the ES cells would be allowed to undergo EB formation and development of Nestin+ cells. Since these Nestin+ cells represent intermediate precursors, infusion of these cells in diabetic mice is likely to promote their in vivo homing to the pancreas. Subsequently, the interactions of Nestin+ cells within the pancreatic microenvironment including the mesenchyme will likely enforce them to generate IPCs. Alternatively, ES cells could be subjected to Activin A treatment to generate DE cells which when infused into diabetic mice will most likely again allow them to home within the pancreas ultimately driving their differentiation into IPCs. The reason that one of these approaches might be more successful is because it has been recently demonstrated that (a) infusion of multipotent stromal cells from human and mouse bone marrow leads to their homing and repair of pancreatic islets and renal glomeruli in streptozotocin treated diabetic NOD/scid mice and (b) stem cells modified with the CXCR4 gene undergo targeted migration to infracted myocardium and improved cardiac performance (Cheng et al., 2008; Hess et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2006). Activin A treatment of ES cells leads to the generation of DE which is characterized by CXCR4 expression and there is evidence that pancreatic inflammation upregulates the CXCR4 ligand SDF1. A similar mechanism might be operational in the mice treated with streptozotocin. Moreover, the pancreatic microenvironment and especially the pancreatic mesenchyme would be more favorable for the in vivo differentiation and maturation of the precursors into functional IPCs. Yet there is also a remote possibility that the infused CXCR4+ cells might undergo fusion with the existing pancreatic β cells within the pancreas and further undergo selective expansion. In such a scenario, it would be interesting to characterize the newly generated IPCs derived from the fused cells. Other potential sources for the generation of IPCs include mesenchymal stromal cells and iPS cells. If successful, mesenchymal stromal cell- and iPS cell-derived IPCs would become potentially useful in the clinical settings since they would not be susceptible to immunological graft rejection post transplantation in the diabetic patients.

d) Selective enrichment of ES cell derived IPCs

This novel approach involves development of strategies for the selective enrichment of ES cell-derived IPCs from a heterogeneous mixture of undifferentiated ES cells as well as cells representing other lineages. Unfortunately, the critical gap in the knowledge of molecular markers specifically expressed on the cell surface by the pancreatic β cells limits the potential utility of this approach. Therefore it would seem logical and more appropriate to develop artificial cell surface surrogate markers that will be selectively expressed on the surface of the functional IPCs and could be used to purify the IPCs. For example, insulin promoter driven artificial, truncated CD4 receptor (lacking intracytoplasmic domain) can be engineered to be expressed selectively on the cell surface of the ES cell-derived IPCs. The IPCs expressing truncated CD4 receptor can be easily purified using anti-CD4 antibodies conjugated to the magnetic beads using magnetic cell separation system (MACS). We believe that this potential approach will have a significant impact especially when testing the therapeutic efficacy of ES cell-derived IPCs since currently all the studies have utilized a heterogeneous mixture of ES cell-derived cells which only contain a tiny fraction of the actual IPCs. Future research efforts need to be directed to identify and characterize new cell surface markers which are specifically expressed on the pancreatic β cells as well as ES cell-derived IPCs.

e) Development of pancreatic β cell specific reporters

An additional powerful strategy is to engineer ES cells using pancreatic β cell specific promoters to drive the expression of various enzymatic and fluorescent reporter molecules. The underlying rationale for using this approach is that once the ES cells enter the lineage commitment pathway towards generation of IPCs, transcriptional activation of the pancreatic β cell specific promoter will lead to reporter gene expression which can easily be monitored quantitatively. This unique approach can be utilized for the high throughput screening of chemical libraries to identify new candidate molecules that enforce and enhance lineage commitment of ES cells into IPCs. We have capitalized on this approach and have successfully engineered mouse ES cells using rat insulin promoter (RIP) to drive the expression of firefly luciferase. Not only can these engineered ES cells be used to monitor their differentiation into IPCs in vitro but this strategy also simultaneously provides the unique opportunity to monitor the long term fate of IPCs in vivo post transplantation in real-time by non invasive bioluminescence imaging (Raikwar, S. and Zavazava, N: manuscript in preparation). We believe that this novel strategy has a significant potential to advance the currently limited field of ES cell differentiation into IPCs. Further, it would be worthwhile to develop mouse ES cell lines by exploiting the RIP to drive conditional expression of pancreatic β cell specific growth factors like GLP1, exendin 4 and INGAP to maximize the number of ESC-derived IPCs. This will prove immensely valuable for the in vivo preclinical testing of the therapeutic efficacy of ESC-derived IPCs where a large number of IPCs will be needed. A recent study has utilized the cytokeratin 19 promoter which is active in pancreatic ductal cells to engineer mouse ES cells to drive the expression of enhanced yellow fluorescent protein. Using this approach in combination with cell-sorting led to isolation of glucose-responsive insulin secreting CK19+ cells with 40fold higher insulin gene expression and 50fold higher insulin content than CK19− cells (Naujok et al., 2008). In an interesting study Shiraki and colleagues have exploited a similar strategy by utilizing ES cells in which Pdx1 promoter drives the expression of GFP to differentiate them into definitive endoderm lineages (Shiraki et al., 2008). Transplantation of partially in vitro differentiated Pdx1+ cells under the renal capsule led to their further differentiation into all three pancreatic lineages including endocrine, exocrine and ductal cells.

Factors Regulating Insulin Secretion

Leptin appears to directly inhibit insulin secretion from pancreatic β cells (Kieffer et al., 1997;Kieffer and Habener, 2000;Seufert et al., 1999;Seufert et al., 1999;Kulkarni et al., 1997). The underlying mechanism is not very clear but apparently involves leptin receptors expressed on the pancreatic β cells which have an inhibitory effect on glucose stimulated insulin secretion as well as proinsulin mRNA. Leptin causes an activation of the ATP-sensitive potassium channels with a resultant hyperpolarization preventing calcium influx and the release of insulin. Thus K(ATP) channel is a direct molecular target of leptin in pancreatic β cells. The pancreatic islets of leptin-deficient ob/ob mice display a drastic reduction of insulin secretion upon leptin stimulation (Seufert et al., 1999). In fact the earliest evidence that leptin is involved in the regulation of insulin came from leptin deficient ob/ob and leptin receptor mutant db/db mice (Baetens et al., 1978;Lee et al., 1996;Seufert et al., 1999;Seufert et al., 1999). The underlying defects in the leptin pathway lead to hyperinsulinemia even before the development of the diabetic obese phenotype (Chen and Romsos, 1995).

HNF-4α, a transcription factor of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily (N2RA1) is widely expressed in the liver, intestine, kidneys and pancreas (Sladek et al., 1990). Heterozygous loss-of-function mutations of the HNF-4α cause maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY1) (Yamagata et al., 1996). The primary cause of MODY1 has been established as an impairment of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by pancreatic β cells thereby indicating that loss of HNF-4α leads to abnormal insulin secretion from the pancreatic β cells (Byrne et al., 1995;Herman et al., 1997;Stoffel and Duncan, 1997;Yang et al., 2000). To investigate the potential role of HNF-4α in the pancreatic β cells, Miura and colleagues have generated β-cell specific HNF-4α knock-out (βHNF-4αKO) mice using the Cre-LoxP system with a RIP driven Cre recombinase (Miura et al., 2006). These βHNF-4αKO mice exhibited impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion despite normal pancreatic islet morphology, β-cell mass and insulin content.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are newly discovered short non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression by targeting the 3’-untranslated region of mRNA thereby preventing their translation (Ambros, 2003;Bartel, 2004;Palatnik et al., 2003). Recent studies have suggested that a pancreatic islet-specific miR-375 plays a direct role in regulating the insulin secretion in pancreatic β cells by targeting myotrophin, a cytoplasmic protein that promotes exocytosis of insulin granules (Poy et al., 2004). Another potential underlying mechanism involves miR-375 mediated downregulation of the target gene PDK1 thereby resulting in decreased glucose-stimulatory action on insulin gene expression and DNA synthesis. Further it has been shown that glucose causes a decrease in miR-375 precursor levels with a concomitant increase in PDK1 protein (El et al., 2008). Inhibition of miR-375 mediated by morpholino knockdown in zebrafish was recently shown to cause defects in the morphology of the pancreatic islets (Kloosterman et al., 2007). Another miRNA miR-9 has been shown to act by diminishing the expression of the transcription factor Onecut-2 and, in turn, by increasing the level of Granuphilin/Slp4, a Rab GTPase effector associated with β cell secretory granules that exerts a negative control on insulin release (Plaisance et al., 2006). Interestingly, Baroukh et al. have identified another pancreatic miRNA miR-124a2 and its target Foxa2 and have shown that increasing the level of miR-124a2 negatively regulates the level of the Foxa2 protein, which in turn, decreases the level of downstream targets of Foxa2 including Pdx1, Kir6.2, and Sur1, resulting in an impairment of insulin biosynthesis and changes in glucose signaling in pancreatic β cell lines (Baroukh et al., 2007). Thus, from the ongoing discussion it is clear that it would be beneficial to characterize the glucose responsive insulin secretion of the ES cell-derived IPCs. This could be accomplished by performing ion channel studies in the presence and absence of agonists like carbachol and tolbutamide and antagonists like nifedipine.

Summary

Development of human ES cell based therapy for diabetes represents one of the most challenging areas of stem cell research. A number of challenges need to be overcome before this new technology can be exploited for treatment of diabetes. For example there is an urgent need to develop new feeder free human ES cell lines. The currently available human ES cell lines have been generated and cultivated on mouse embryonic feeders and require serum of bovine origin which poses a significant risk in terms of zoonotic transmission of viral diseases. Thus, it is highly desirable to optimize feeder free and serum free cultivation of human ES cells. The next important challenge is to develop novel strategies for maximizing the differentiation of human ES cells into IPCs. Although the currently available protocols have significantly improved the generation of ES cell-derived IPCs, they are very expensive and labor intensive with only a tiny fraction of the finally differentiated IPCs. High throughput screening of small molecules might identify novel compounds that might improve the ES cell differentiation of IPCs. Additionally, it would be useful to identify novel cell surface markers on the ES cell derived IPCs. Thus, improved separation methods of differentiated IPCs might yield higher numbers of IPCs, eliminating teratoma forming ES cells. The currently available protocols generate IPCs that have low glucose responsiveness and poor insulin secretion. Therefore, future studies must be directed towards examining the molecular mechanisms governing glucose stimulated insulin secretion. Traditionally streptozotocin induced diabetes in mice has been used to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of ES cell-derived IPCs. This model does not fully recapitulate the true diabetic pathophysiology of human type I diabetes. In fact, streptozotocin treatment leads to the generation of extrapancreatic IPCs in multiple organs including liver, adipose tissue, spleen, bone marrow and thymus (Kojima et al., 2004). Thus, there is a need to develop novel mouse models of diabetes for testing the therapeutic efficacy of ES cell-derived IPCs. In this regard, the NOD and the NOD-SCID mice might prove immensely beneficial since they represent a model that very closely mimics type 1diabetes in humans. Despite rapid advances and rapid progress in this new field, many obstacles remain to be overcome. We believe that once these significant challenges have been met, we would be closer to evaluating the therapeutic potential of human ES cell-derived IPCs in type 1 diabetes patients.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by Grant Number NIH/NHLBI #R01 HLO73015, a VA Merit Review Award, and a grant by the ROTRF to N.Z. and by an NIH Pilot Grant to S.R. from the University of Iowa, Center for Gene Therapy of Cystic Fibrosis and Other Genetic Diseases, NIH/NIDDK Grant 5P30DK54759-10.

References

- Chan KM, Raikwar SP, Zavazava N. Strategies for differentiating embryonic stem cells (ESC) into insulin-producing cells and development of non-invasive imaging techniques using bioluminescence. Immunol Res. 2007;39:261–270. doi: 10.1007/s12026-007-0070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raikwar SP, Mueller T, Zavazava N. Strategies for developing therapeutic application of human embryonic stem cells. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006;21:19–28. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00034.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna J, Wernig M, Markoulaki S, Sun CW, Meissner A, Cassady JP, Beard C, Brambrink T, Wu LC, Townes TM, Jaenisch R. Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin. Science. 2007;318:1920–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.1152092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Okita K, Mochiduki Y, Takizawa N, Yamanaka S. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, Yabuuchi A, Huo H, Ince TA, Lerou PH, Lensch MW, Daley GQ. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, ntosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, Brambrink T, Ku M, Hochedlinger K, Bernstein BE, Jaenisch R. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, Jones JM. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumelsky N, Blondel O, Laeng P, Velasco I, Ravin R, McKay R. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells to insulin-secreting structures similar to pancreatic islets. Science. 2001;292:1389–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.1058866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo E, McKay R. Proliferation and differentiation of neuronal stem cells regulated by nerve growth factor. Nature. 1990;347:762–765. doi: 10.1038/347762a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey RK, Bucay N, Beattie GM, Lopez A, Messam CA, Cirulli V, Hayek A. Characterization and isolation of promoter-defined nestin-positive cells from the human fetal pancreas. Diabetes. 2003;52:2519–2525. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.10.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein T, Ling Z, Heimberg H, Madsen OD, Heller RS, Serup P. Nestin is expressed in vascular endothelial cells in the adult human pancreas. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:697–706. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardon J, Rooman I, Bouwens L. Nestin expression in pancreatic stellate cells and angiogenic endothelial cells. Histochem Cell Biol. 2002;117:535–540. doi: 10.1007/s00418-002-0412-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendahl U, Zimmerman LB, McKay RD. CNS stem cells express a new class of intermediate filament protein. Cell. 1990;60:585–595. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulewski H, Abraham EJ, Gerlach MJ, Daniel PB, Moritz W, Muller B, Vallejo M, Thomas MK, Habener JF. Multipotential nestin-positive stem cells isolated from adult pancreatic islets differentiate ex vivo into pancreatic endocrine, exocrine, and hepatic phenotypes. Diabetes. 2001;50:521–533. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.3.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treutelaar MK, Skidmore JM, as-Leme CL, Hara M, Zhang L, Simeone D, Martin DM, Burant CF. Nestin-lineage cells contribute to the microvasculature but not endocrine cells of the islet. Diabetes. 2003;52:2503–2512. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.10.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maria-Engler SS, Correa-Giannella ML, Labriola L, Krogh K, Colin C, Lojudice FH, Aita CA, de Oliveira EM, Correa TC, da SI, Genzini T, de Miranda MP, Noronha IL, Vilela L, Coimbra CN, Mortara RA, Guia MM, Eliaschewitz FG, Sogayar MC. Co-localization of nestin and insulin and expression of islet cell markers in long-term human pancreatic nestin-positive cell cultures. J Endocrinol. 2004;183:455–467. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.05703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delacour A, Nepote V, Trumpp A, Herrera PL. Nestin expression in pancreatic exocrine cell lineages. Mech Dev. 2004;121:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esni F, Stoffers DA, Takeuchi T, Leach SD. Origin of exocrine pancreatic cells from nestin-positive precursors in developing mouse pancreas. Mech Dev. 2004;121:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolletschek A, Kania G, Wobus AM. Generation of pancreatic insulin-producing cells from embryonic stem cells - 'proof of principle', but questions still unanswered. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2541–2545. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0441-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd AS, Wu DC, Higashi Y, Wood KJ. A comparison of protocols used to generate insulin-producing cell clusters from mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1128–1137. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson M, Tonning A, Frandsen U, Petri A, Rajagopal J, Englund MC, Heller RS, Hakansson J, Fleckner J, Skold HN, Melton D, Semb H, Serup P. Artifactual insulin release from differentiated embryonic stem cells. Diabetes. 2004;53:2603–2609. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.10.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal J, Anderson WJ, Kume S, Martinez OI, Melton DA. Insulin staining of ES cell progeny from insulin uptake. Science. 2003;299:363. doi: 10.1126/science.1077838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipione S, Eshpeter A, Lyon JG, Korbutt GS, Bleackley RC. Insulin expressing cells from differentiated embryonic stem cells are not beta cells. Diabetologia. 2004;47:499–508. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1349-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria B, Roche E, Berna G, Leon-Quinto T, Reig JA, Martin F. Insulin-secreting cells derived from embryonic stem cells normalize glycemia in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2000;49:157–162. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyszczuk P, Czyz J, Kania G, Wagner M, Roll U, St-Onge L, Wobus AM. Expression of Pax4 in embryonic stem cells promotes differentiation of nestin-positive progenitor and insulin-producing cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:998–1003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237371100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori Y, Rulifson IC, Tsai BC, Heit JJ, Cahoy JJ, Kim SK. Growth inhibitors promote differentiation of insulin-producing tissue from embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16105–16110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252618999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa T, Oh SH, Pi L, Hatch HM, Shupe T, Petersen BE. Teratoma formation leads to failure of treatment for type I diabetes using embryonic stem cell-derived insulin-producing cells. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1781–1791. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62488-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo A, Shinozaki K, Shannon JM, Kouskoff V, Kennedy M, Woo S, Fehling HJ, Keller G. Development of definitive endoderm from embryonic stem cells in culture. Development. 2004;131:1651–1662. doi: 10.1242/dev.01044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amour KA, Bang AG, Eliazer S, Kelly OG, Agulnick AD, Smart NG, Moorman MA, Kroon E, Carpenter MK, Baetge EE. Production of pancreatic hormone-expressing endocrine cells from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1392–1401. doi: 10.1038/nbt1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean AB, D'Amour KA, Jones KL, Krishnamoorthy M, Kulik MJ, Reynolds DM, Sheppard AM, Liu H, Xu Y, Baetge EE, Dalton S. Activin a efficiently specifies definitive endoderm from human embryonic stem cells only when phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling is suppressed. Stem Cells. 2007;25:29–38. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon E, Martinson LA, Kadoya K, Bang AG, Kelly OG, Eliazer S, Young H, Richardson M, Smart NG, Cunningham J, Agulnick AD, D'Amour KA, Carpenter MK, Baetge EE. Pancreatic endoderm derived from human embryonic stem cells generates glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:443–452. doi: 10.1038/nbt1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaing M, Peault B, Basmaciogullari A, Casal I, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R. Blood glucose normalization upon transplantation of human embryonic pancreas into beta-cell-deficient SCID mice. Diabetologia. 2001;44:2066–2076. doi: 10.1007/s001250100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaing M, Duvillie B, Quemeneur E, Basmaciogullari A, Scharfmann R. Ex vivo analysis of acinar and endocrine cell development in the human embryonic pancreas. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:339–345. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayek A, Beattie GM. Experimental transplantation of human fetal and adult pancreatic islets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:2471–2475. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.8.4151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuch BE, Osgerby KJ, Turtle JR. Reversal of diabetes in hyperglycaemic nude mice by human fetal pancreas. Transplant Proc. 1989;21:2665–2666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Hwang DY, Yoon S, Isacson O, Ramezani A, Hawley RG, Kim KS. Functional analysis of various promoters in lentiviral vectors at different stages of in vitro differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1630–1639. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Kim GJ, Miyoshi H, Moon SH, Ahn SE, Lee JH, Lee HJ, Cha KY, Chung HM. Efficiency of the elongation factor-1alpha promoter in mammalian embryonic stem cells using lentiviral gene delivery systems. Stem Cells Dev. 2007;16:537–545. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew CG, Draper JS, Walsh J, Moore H, Andrews PW. Transient and stable transgene expression in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1521–1528. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki S, Yamato E, Miyazaki J. Regulated expression of pdx-1 promotes in vitro differentiation of insulin-producing cells from embryonic stem cells. Diabetes. 2004;53:1030–1037. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent R, Treff N, Budde M, Kastenberg Z, Odorico J. Generation and characterization of novel tetracycline-inducible pancreatic transcription factor-expressing murine embryonic stem cell lines. Stem Cells Dev. 2006;15:953–962. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.15.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavon N, Yanuka O, Benvenisty N. The effect of overexpression of Pdx1 and Foxa2 on the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into pancreatic cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1923–1930. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafimidis I, Rakatzi I, Episkopou V, Gouti M, Gavalas A. Novel effectors of directed and Ngn3-mediated differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into endocrine pancreas progenitors. Stem Cells. 2008;26:3–16. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treff NR, Vincent RK, Budde ML, Browning VL, Magliocca JF, Kapur V, Odorico JS. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells conditionally expressing neurogenin 3. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2529–2537. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, Rodriguez RT, McLean GW, Kim SK. Conserved markers of fetal pancreatic epithelium permit prospective isolation of islet progenitor cells by FACS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:175–180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609490104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao CS, Loomis ZL, Lee JE, Sussel L. Genetic identification of a novel NeuroD1 function in the early differentiation of islet alpha, PP and epsilon cells. Dev Biol. 2007;312:523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z, Ou L, Zhou X, Li F, Jia X, Zhang Y, Liu X, Li Y, Ward CA, Melo LG, Kong D. Targeted migration of mesenchymal stem cells modified with CXCR4 gene to infarcted myocardium improves cardiac performance. Mol Ther. 2008;16:571–579. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess D, Li L, Martin M, Sakano S, Hill D, Strutt B, Thyssen S, Gray DA, Bhatia M. Bone marrow-derived stem cells initiate pancreatic regeneration. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:763–770. doi: 10.1038/nbt841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RH, Seo MJ, Reger RL, Spees JL, Pulin AA, Olson SD, Prockop DJ. Multipotent stromal cells from human marrow home to and promote repair of pancreatic islets and renal glomeruli in diabetic NOD/scid mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17438–17443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608249103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naujok O, Francini F, Jorns A, Lenzen S. An efficient experimental strategy for mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation and separation of a cytokeratin-19-positive population of insulin-producing cells. Cell Prolif. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraki N, Yoshida T, Araki K, Umezawa A, Higuchi Y, Goto H, Kume K, Kume S. Guided differentiation of embryonic stem cells into Pdx1-expressing regional-specific definitive endoderm. Stem Cells. 2008;26:874–885. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer TJ, Heller RS, Leech CA, Holz GG, Habener JF. Leptin suppression of insulin secretion by the activation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 1997;46:1087–1093. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.6.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer TJ, Habener JF. The adipoinsular axis: effects of leptin on pancreatic beta-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;278:E1–E14. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.1.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seufert J, Kieffer TJ, Leech CA, Holz GG, Moritz W, Ricordi C, Habener JF. Leptin suppression of insulin secretion and gene expression in human pancreatic islets: implications for the development of adipogenic diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:670–676. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.2.5460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seufert J, Kieffer TJ, Habener JF. Leptin inhibits insulin gene transcription and reverses hyperinsulinemia in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:674–679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni RN, Wang ZL, Wang RM, Hurley JD, Smith DM, Ghatei MA, Withers DJ, Gardiner JV, Bailey CJ, Bloom SR. Leptin rapidly suppresses insulin release from insulinoma cells, rat and human islets and, in vivo, in mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2729–2736. doi: 10.1172/JCI119818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baetens D, Stefan Y, Ravazzola M, Malaisse-Lagae F, Coleman DL, Orci L. Alteration of islet cell populations in spontaneously diabetic mice. Diabetes. 1978;27:1–7. doi: 10.2337/diab.27.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GH, Proenca R, Montez JM, Carroll KM, Darvishzadeh JG, Lee JI, Friedman JM. Abnormal splicing of the leptin receptor in diabetic mice. Nature. 1996;379:632–635. doi: 10.1038/379632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen NG, Romsos DR. Enhanced sensitivity of pancreatic islets from preobese 2-week-old ob/ob mice to neurohormonal stimulation of insulin secretion. Endocrinology. 1995;136:505–511. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.2.7835283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sladek FM, Zhong WM, Lai E, Darnell JE., Jr Liver-enriched transcription factor HNF-4 is a novel member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2353–2365. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata K, Furuta H, Oda N, Kaisaki PJ, Menzel S, Cox NJ, Fajans SS, Signorini S, Stoffel M, Bell GI. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha gene in maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY1) Nature. 1996;384:458–460. doi: 10.1038/384458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne MM, Sturis J, Fajans SS, Ortiz FJ, Stoltz A, Stoffel M, Smith MJ, Bell GI, Halter JB, Polonsky KS. Altered insulin secretory responses to glucose in subjects with a mutation in the MODY1 gene on chromosome 20. Diabetes. 1995;44:699–704. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.6.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman WH, Fajans SS, Smith MJ, Polonsky KS, Bell GI, Halter JB. Diminished insulin and glucagon secretory responses to arginine in nondiabetic subjects with a mutation in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha/MODY1 gene. Diabetes. 1997;46:1749–1754. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.11.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffel M, Duncan SA. The maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY1) transcription factor HNF4alpha regulates expression of genes required for glucose transport and metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13209–13214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Yamagata K, Yamamoto K, Cao Y, Miyagawa J, Fukamizu A, Hanafusa T, Matsuzawa Y. R127W-HNF-4alpha is a loss of function mutation but not a rare polymorphism and causes Type II diabetes in a Japanese family with MODY1. Diabetologia. 2000;43:520–524. doi: 10.1007/s001250051338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura A, Yamagata K, Kakei M, Hatakeyama H, Takahashi N, Fukui K, Nammo T, Yoneda K, Inoue Y, Sladek FM, Magnuson MA, Kasai H, Miyagawa J, Gonzalez FJ, Shimomura I. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha is essential for glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by pancreatic beta-cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5246–5257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507496200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V. MicroRNA pathways in flies and worms: growth, death, fat, stress, and timing. Cell. 2003;113:673–676. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00428-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palatnik JF, Allen E, Wu X, Schommer C, Schwab R, Carrington JC, Weigel D. Control of leaf morphogenesis by microRNAs. Nature. 2003;425:257–263. doi: 10.1038/nature01958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poy MN, Eliasson L, Krutzfeldt J, Kuwajima S, Ma X, Macdonald PE, Pfeffer S, Tuschl T, Rajewsky N, Rorsman P, Stoffel M. A pancreatic islet-specific microRNA regulates insulin secretion. Nature. 2004;432:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature03076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El OA, Baroukh N, Martens GA, Lebrun P, Pipeleers D, Van OE. miR-375 targets PDK1 and regulates glucose-induced biological responses in pancreatic {beta}-cells. Diabetes. 2008 doi: 10.2337/db07-1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloosterman WP, Lagendijk AK, Ketting RF, Moulton JD, Plasterk RH. Targeted inhibition of miRNA maturation with morpholinos reveals a role for miR-375 in pancreatic islet development. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaisance V, Abderrahmani A, Perret-Menoud V, Jacquemin P, Lemaigre F, Regazzi R. MicroRNA-9 controls the expression of Granuphilin/Slp4 and the secretory response of insulin-producing cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26932–26942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601225200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroukh N, Ravier MA, Loder MK, Hill EV, Bounacer A, Scharfmann R, Rutter GA, Van OE. MicroRNA-124a regulates Foxa2 expression and intracellular signaling in pancreatic beta-cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19575–19588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611841200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima H, Fujimiya M, Matsumura K, Nakahara T, Hara M, Chan L. Extrapancreatic insulin-producing cells in multiple organs in diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2458–2463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308690100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]