Abstract

Celiac disease (CD) is a type of intestinal malabsorption syndrome, in which the patients are intolerant to the gliadin in dietary gluten, resulting in chronic diarrhea and secondary malnutrition. The disease is common in Europe and the United States, but only sporadic reports are found in East Asia including China. Is CD really rare in China? We examined 62 patients by capsule endoscopy for chronic diarrhea from June 2003 to March 2008. Four patients with chronic diarrhea and weight loss were diagnosed to have CD. Under the capsule endoscopy, we observed that the villi of the proximal small bowel became short, and that the mucous membrane became atrophied in these four patients. Duodenal biopsies were performed during gastroscopy and the pathological changes of mucosa were confirmed to be Marsh 3 stage of CD. A gluten free diet significantly improved the conditions of the four patients. We suspect that in China, especially in the northern area where wheat is the main food, CD might not be uncommon, and its under-diagnosis could be caused by its clinical manifestations that could be easily covered by the symptoms from other clinical situations, particularly when it came to subclinical patients without obvious symptom or to patients with extraintestinal symptoms as the initial manifestations.

Keywords: Celiac disease (CD), China, Gluten, Prevalence, Capsule endoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Celiac disease (CD), also known as idiopathic steatorrhea, non-tropical sprue and gluten enteropathy, is a kind of intestinal malabsorption syndrome that has a certain extent of genetic susceptibility. After ingesting wheat products containing gluten, CD occurs in patients intolerant of the gliadin in gluten, resulting in the damage of proximal small bowel. The clinical symptoms are mainly chronic diarrhea caused by intestinal malabsorption and secondary malnutrition. People used to believe that CD was common in Europe, Australia, and North America, with the prevalence between 0.5% and 1% (Cataldo and Montalto, 2007). Caucasian is an especially susceptible population. In East Asia, including China, Japan, South Korea, and Mongolia, CD is thought to be very rare. We investigated 62 patients with chronic diarrhea in Zhejiang Province, China, for the incidence of CD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 62 patients (42 males and 20 females, aged 19~75 years) included in this study were recruited from June 2003 to March 2008 from the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China. All participants have presented chronic diarrhea for 3 months to 20 years. Pregnant women, patients with pace-makers, and patients with intestinal obstruction were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, and the informed consent was obtained from each of the participants. All the 62 patients were examined by capsule endoscopy (Given Imaging, Ltd., Israel), colonoscopy, and gastroscopy. A careful review of their lab results and medical histories has been performed. Two senior gastroenterologists and one senior pathologist were assigned to review the capsule endoscopy data and the pathological changes of duodenal mucosa.

RESULTS

By capsule endoscopy and pathological changes of duodenal mucosa, 6.5% patients (4/62) were diagnosed to have CD. These 4 CD patients were of Han nationality, including 3 males and 1 female, aged between 28 and 73 years. The main symptoms of these patients were repeated diarrhea, weight loss, and debilitation, which lasted for 4 month to 1 year (Table 1).

Table 1.

Main clinical and laboratory data of the four CD patients

| Patient No. | Gender | Age (year) | Vocation | Course (month) | Main symptoms | Weight loss (kg) | Hemoglobin (g/L) | Albumin (g/L) | Globulin (g/L) | Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | Serum potassium (mmol/L) | Serum calcium (mmol/L) | Pathological type |

| Case 1 | Male | 28 | Painter | 4 | Diarrhea, weight loss, loss of appetite, fatigue | 15 | 92 | 36 | 13.0 | 1.68 | 3.40 | 2.02 | Marsh 3 |

| Case 2 | Male | 73 | Farmer | 6 | Diarrhea, weight loss, fatigue, lower limb edema | 15 | 77 | 27 | 28.5 | 2.89 | 2.99 | 1.89 | Marsh 3 |

| Case 3 | Male | 28 | Businessman | 12 | Diarrhea, weight loss, fatigue | 8 | 101 | 36 | 20.5 | 2.96 | 3.50 | 2.07 | Marsh 3 |

| Case 4 | Female | 45 | Farmer | 5 | Diarrhea, weight loss, weakness, lower limb edema, ascites | 10 | 95 | 28 | 22.0 | 1.56 | 3.20 | 1.95 | Marsh 3 |

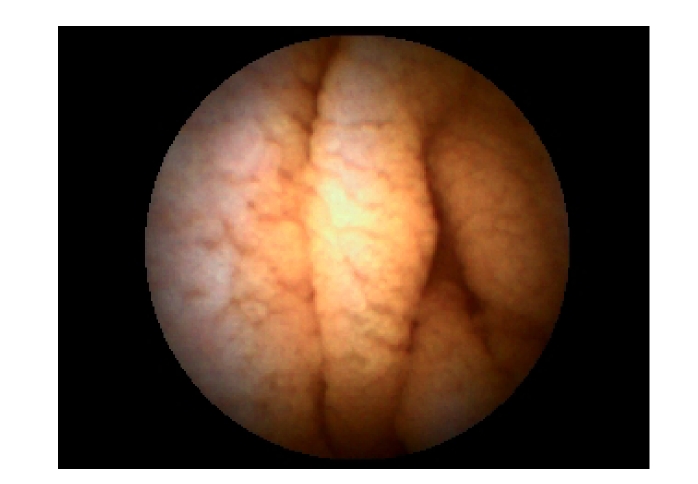

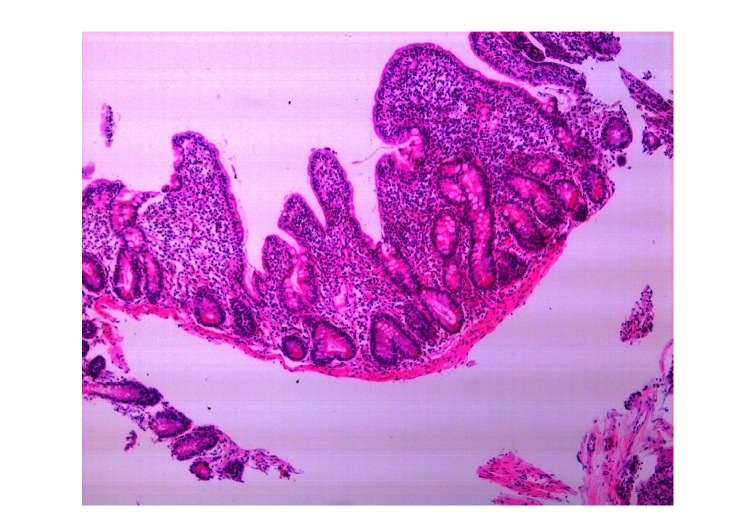

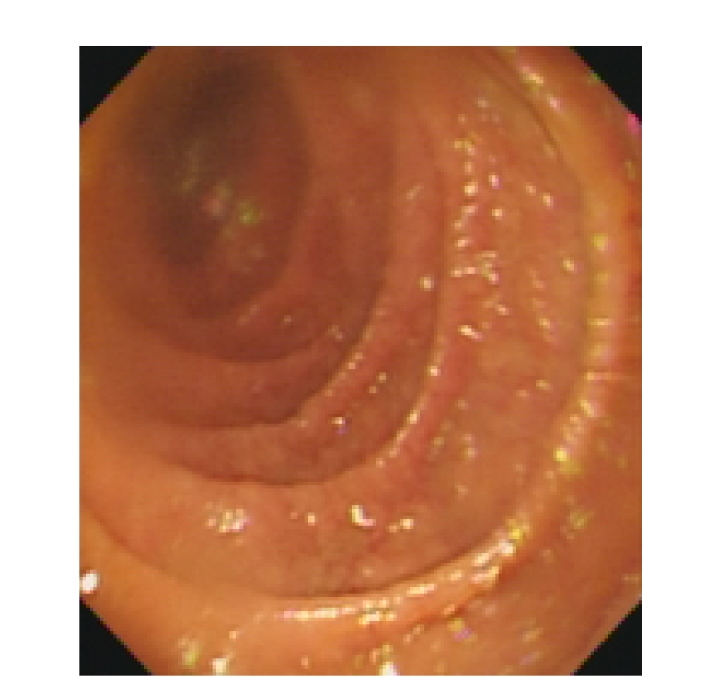

In the early stages, antibiotics were used for 1~2 weeks but had no effects. We found that these four patients had varying degrees of anemia, decreased levels of globulin, albumin and total cholesterol, and different extent of electrolyte imbalance, mainly low levels of potassium and calcium. One of the four patients also had hyponatremia, which could be corrected by intravenous fluid and electrolyte replacement. After intravenous injection of albumin, the ascites and edema of the lower limbs caused by hypoproteinemia in two of the four patients disappeared. No abnormalities were found in any of the four patients by colonoscopy. Under capsule endoscopy of the small intestine, we observed the following changes: the shortened villi of the duodenum and the jejunum, extensive mucosal atrophy, as well as rhagades in the mucous membranes (Fig.1). Mainly proximal small bowel was affected, while the distal small bowel was normal. Under gastroscope, the mucosae in the descending duodenum were found to be atrophied (Fig.2). Descending duodenum biopsy was performed during gastroscopy on the four patients. The pathological changes of the mucosa in the descending duodenum were as follows: blunting of the villi, crypt hyperplasia, and a large number of lymphocytes infiltrating the epithelial cells, all of which were consistent with Marsh 3 stage of CD (Fig.3).

Fig. 1.

Changes under capsule endoscopy: shortened villi, extensive mucosal atrophy, and rhagades in mucous membrane

Fig. 2.

Changes under gastroscope: extensive duodenum mucosal atrophy

Fig. 3.

Pathological changes by descending duodenum biopsy: blunting of villi, crypt hyperplasia, a large number of lymphocytes infiltrating the epithelial cells, all of which were consistent with Marsh 3 of CD

After being diagnosed as CD, these patients were instructed to stop eating wheat products such as noodles, bread, steamed bread, and biscuits. Two months later, these four patients recovered completely, gaining weight by 5~8 kg, and were back to normal life. After being cured, two patients switched back to previous diet, and one developed repeated diarrhea again within two months, but the other did not.

DISCUSSION

It has been believed that CD mainly occurs in Caucasians; however, its prevalence in other populations might be underestimated. Especially, in developing countries the diagnosed patients could be only the tip of the iceberg. In immigrants worldwide, it was found that the disease could occur in people from various races. A multi-center study of CD prevalence in immigrant children in Italy reported three CD patients from Pakistan and one from Sri Lanka (Cataldo et al., 2004). CD was also found in people of African descent living in Europe (Bonamico et al., 1994), and in people in Latin America (Galvao et al., 1992; Rabassa et al., 1981; Sagaro and Jimenez, 1981; Hung et al., 1995). In recent years, the serological screening for CD has developed rapidly, due mainly to the generation of the antigliadin antibody (AGA), endomysial antibody (EMA), and tissue transglutaminase antibody (tTG-Ab) (Hopper et al., 2008). In developing countries, screenings of large samples found that the prevalence of CD in these areas was similar to that in Europe and the United States. In a screening of 2500 healthy blood donors in Tunisia, the positive ratio of EMA was 2.82% (Mankai et al., 2006), which was close to that of the Europeans. In South Asia, 26%~49% Indian children suffering from chronic diarrhea are intolerant of gluten (Yachha et al., 1993; Bhatnagar et al., 2005).

It was generally believed that CD is very rare in the Far East, including China, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, etc. (Fasano and Catassi, 2001), and there were only sporadic reports of the disease in the East Asia (Freeman, 2003; Makishima et al., 2006). However, this conclusion has not been confirmed by large-scale serological screening in this region. As the prevalence of CD has increased in developing countries, we believe that CD should be considered as an endemic disease. In this study, 4 out of 62 patients with chronic diarrhea were diagnosed with CD, accounting for 6.5% of the patients surveyed. If we take this fact into consideration that rice, not wheat, is the main food in Zhejiang Province, an area within southern China, the prevalence of CD may be even higher in northern China, where wheat is the main food. Therefore, we speculate that CD may not be rare in China.

There could be a few factors that affect the diagnosis of CD in China. Firstly, the main symptom of CD can be easily covered by symptoms caused by other clinical situations. Typically, pathological changes of CD include intestinal mucosal atrophy, flattening of the villi, deepening of the crypt, cubic-like columnar epithelial cells, scarce brush borders, and a great quantity of inflammatory cell infiltration. However, among the pathological changes associated with CD, a great amount of inflammatory cell infiltration may be the only manifestation seen at the early stage of the disease, while the flattening of villi and mucosal atrophy prominent occur later. Marsh (1992) and Marsh and Crowe (1995) categorized this disease into 5 stages as follows: 0, pre-infiltration period; 1, infiltration period; 2, infiltration/proliferation period; 3, flat destruction period; 4, atrophic/hypoplastic period. The failure to recognize the early and mild pathological changes in intestinal biopsy samples might have frequently resulted in a missed diagnosis of CD, accounting for its underestimated prevalence. Therefore, we should pay more attention to this disease, especially to those patients at Marsh 0~2 stages. In our hospital, the first CD patient was diagnosed with the help of American pathologists (Dr. Kevin Thompson and Dr. Jun Wang, GI/Liver pathologists, Loma Linda University, USA). Secondly, some CD patients have extraintestinal symptoms, such as anemia, osteoarthritis, peripheral neuropathy, and endocrine abnormalities, as initial symptoms (Corazza and Gasbarrini, 1995), and some subclinical patients had very mild symptoms or even no symptom. These silent and latent forms of CD further contribute to the underestimated prevalence of CD. Thirdly, in many regions of China, rice rather than wheat is the staple diet, which makes people with the predisposing CD gene to present only latent forms of CD. All these reasons may have made CD under-diagnosed in China.

The prognosis of CD patients depends on the timing of treatment. Most patients are sensitive to gluten free diet (the standard treatment), so their symptoms improve significantly after 1~2 weeks of diet treatment and their small intestinal injuries recover gradually 6~12 months later. Even for those subclinical patients with no symptom, there can be pathologic changes in the mucous membrane of the small intestine, such as lymphocyte infiltration with crypt proliferation (Marsh and Crowe, 1995), and long-term lymphocyte infiltration and inflammation in mucous membrane of the small intestine, as well as the increase of the morbidity of T cell lymphoma (Mayer et al., 1991; Goldacre et al., 2008; Makishima et al., 2006). Therefore, timely diagnosis is the key to prevent worsening of CD and improve the prognosis of CD. In China, it is important to carry out serological examination and gene screening not only in suspicious patients and high-risk groups (first-degree relatives of CD patients, and patients with type 1 diabetes, herpes dermatitis, etc.), but also in the general “healthy” population.

References

- 1.Bhatnagar S, Gupta SD, Mathur M, Phillips AD, Kumar R, Knutton S, Unsworth DJ, Lock RJ, Natchu UC, Mukhopadhyaya S, et al. Celiac disease with mild to moderate histologic changes is a common cause of chronic diarrhea in Indian children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41(2):204–209. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000172261.24115.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonamico M, Mariani P, Triglione P, Lionetti P, Ferrante P, Petronzelli F, Morellini M, Mazzilli MC. Celiac disease in two sisters with a mother from Cape Verde Island, Africa: a clinical and genetic study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1994;18(1):96–99. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199401000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cataldo F, Montalto G. Celiac disease in the developing countries: a new and challenging public health problem. World J Gastroenterology. 2007;13(15):2153–2159. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i15.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cataldo F, Pitarresi N, Accomando S, Greco L SIGENP, GLNBI Working Group on Coeliac Disease. Epidemiological and clinical features in immigrant children with celiac disease: an Italian multicenter study. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36(11):722–729. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corazza GR, Gasbarrini G. Celiac disease in adult. Baillière’s Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;9(2):329–350. doi: 10.1016/0950-3528(95)90034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fasano A, Catassi C. Current approaches to diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease: an evolving spectrum. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(3):636–651. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman HJ. Biopsy-defined adult celiac disease in Asian-Canadians. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17(7):433–436. doi: 10.1155/2003/789139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galvao LC, Gomes RC, Ramos AM. Celiac disease: report of 20 cases in Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil. Arq Gastroenterol. 1992;29(1):28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldacre MJ, Wotton CJ, Yeates D, Seagroatt V, Jewell D. Cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease and coeliac disease: record linkage study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20(4):297–304. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f2a5e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopper AD, Hadjivassiliou M, Hurlstone DP, Lobo AJ, McAlindon ME, Egner W, Wild G, Sanders DS. What is the role of serologic testing in celiac disease? A prospective, biopsy-confirmed study with economic analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(3):314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hung JC, Phillips AD, Walker-Smith JA. Coeliac disease in children of West Indian origin. Arch Dis Child. 1995;73(2):166–167. doi: 10.1136/adc.73.2.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makishima H, Ito T, Kodama R, Asano N, Nakazawa H, Hirabayashi K, Nakamura S, Ota M, Akamatsu T, Kiyosawa K, et al. Intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma associated with celiac disease: a Japanese case. Int J Hematol. 2006;83(1):63–65. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.05131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mankai A, Landolsi H, Gueddah L, Limem M, Ben , Abdessalem M, Yacoub-Jemni S, Ghannem H, Jeddi M, Ghedira I, Chahed A. Celiac disease in Tunisia: serological screening in healthy blood donors. Pathol Biol, Paris. 2006;54(1):10–13. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marsh MN. Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine: a molecular and immunologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity (celiac sprue) Gastroenterology. 1992;102(1):330–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marsh MN, Crowe PT. Morphology of the mucosal lesion in gluten sensitivity. Baillière’s Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;9(2):273–293. doi: 10.1016/0950-3528(95)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer M, Greco L, Troncone R, Auricchio S, Marsh MN. Compliance of adolescents with coeliac disease with a gluten free diet. Gut. 1991;32(8):881–885. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.8.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabassa EB, Sagaro E, Fragoso T, Castaneda C, Gra B. Coeliac disease in Cuban children. Arch Dis Child. 1981;56(2):128–131. doi: 10.1136/adc.56.2.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sagaro E, Jimenez N. Family studies of coeliac disease in Cuba. Arch Dis Child. 1981;56(2):132–133. doi: 10.1136/adc.56.2.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yachha SK, Misra S, Malik AK, Nagi B, Mehta S. Spectrum of malabsorption syndrome in north Indian children. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1993;12(4):120–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]