Abstract

The treatment and prognosis of labral tears of the hip depend primarily on whether there is concomitant injury of the adjacent acetabular articular cartilage. We asked whether a delamination cyst on the preoperative plain radiographs correlated with delamination of the acetabular articular cartilage at the time of hip arthroscopy. We reviewed the preoperative radiographs of 125 consecutive hips that had a labral tear at hip arthroscopy for the presence of a delamination cyst. A delamination cyst was defined as an acetabular subchondral cyst either directly adjacent to a lateral acetabular cyst or in relation to a subchondral crack in the anterosuperior portion of the acetabulum. All patients with acetabular cartilage delamination at arthroscopy were identified. There were 16 patients with delamination cysts on radiographs and 15 patients with cartilage delamination at arthroscopy. A delamination cyst on the preoperative anteroposterior and/or frog lateral radiographs of the hip accurately predicted acetabular cartilage delamination, especially in hips with labral tears not caused by a major trauma. A delamination cyst is a previously unrecognized and novel radiographic sign that can preoperatively identify acetabular cartilage delamination in patients with labral tears, thereby facilitating the selection of the appropriate surgery and determining prognosis.

Level of Evidence: Level II, diagnostic study. See the Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

The prognosis of patients with labral tears is multifactorial, but status of the acetabular cartilage remains the most important factor in predicting patient outcome [6, 17, 34, 42]. As a result, treatment of labral tears depends on the severity of the labral injury and whether there is concomitant injury and delamination of the adjacent articular cartilage. Femoroacetabular impingement is recognized as one of the major causes of labral tears of the hip [24, 36, 45, 46]. Depending on the status of the acetabular articular cartilage, labral tears secondary to femoroacetabular impingement can be treated by various surgical procedures, including arthroscopic débridement, labral reattachment, labral surgery with concomitant chondral microfracture, or labral surgery with open or arthroscopic femoral head-neck osteochondroplasty [8, 10, 11, 30, 31, 34, 39, 40]. The outcomes, complications, and postoperative recovery after these procedures are very different [6, 10, 16, 17, 30, 31, 37, 42]. Therefore, preoperative knowledge of the status of the articular cartilage adjacent to the labral tear is critical for appropriate surgical decision making and for counseling patients regarding their prognosis and recovery. There currently is no simple and reproducible noninvasive technique to determine if there is delamination of the acetabular articular cartilage adjacent to a labral tear [5, 7, 15, 23, 43]. To date, the only accurate method of assessing the acetabular cartilage is by observation during arthroscopy [7, 12, 13, 24, 25, 38, 44].

The purpose of this study was to identify patients who underwent hip arthroscopy for a labral tear and who had delamination of the articular cartilage and then to correlate the delamination with the presence of a previously undescribed finding on the preoperative plain radiographs, a delamination cyst. Additionally, we assessed all the delamination cysts to determine their location, size, appearance, and associated radiographic findings. Finally, we determined the sensitivity and specificity of the delamination cyst to predict articular cartilage delamination.

Materials and Methods

We identified from our prospective surgical database 142 consecutive hips (140 patients) that underwent a hip arthroscopy by the senior author (MT) between July 2001 and December 2006 and had a labral tear. Of the 142 hip arthroscopies, 17 hips (17 patients) were excluded because we could not obtain their preoperative radiographs. Therefore, 125 hips in 123 patients were available for review. There were 98 female patients and 23 male patients, with an average age of 39 years (range, 15–72 years). The labral tear involved the right hip in 64 cases and the left in 61 cases.

All patients in this study had hip arthroscopy in the supine position on a fracture table with an offset perineal post and the involved leg abducted 20° to 25°. Under fluoroscopic guidance, we applied traction to the leg and a standard anterolateral portal was established [9]. After we inserted a 70° scope, the anterior portal was established and we performed arthroscopy of the hip. All patients who had a labral tear, either isolated or in conjunction with other hip disorders, were included in this study.

From the prospective surgical database, we obtained patient demographics, presence or absence of mechanical symptoms, disease duration, onset of symptoms as classified by Byrd and Jones [4, 6] (traumatic from a major trauma such as violent impact or dislocation, acute from a twisting episode, or a well-defined precipitating event or insidious with a gradual onset and worsening symptoms), preoperative radiographic findings, and intraoperative findings. In each case, the preoperative anteroposterior (AP) pelvis and AP, lateral, and frog lateral hip radiographs were reviewed by a blinded independent observer (MG) for the presence of boney abnormalities of the acetabulum and/or femur and arthritic changes [2, 16, 18, 27, 46]. The radiographs were examined carefully to identify any subchondral acetabular cysts. Subchondral cysts in the lateral aspect of the roof of the acetabulum have been described in association with a labral tear [14, 20, 44]. The presence of these lateral acetabular cysts and delamination cysts was recorded for each case.

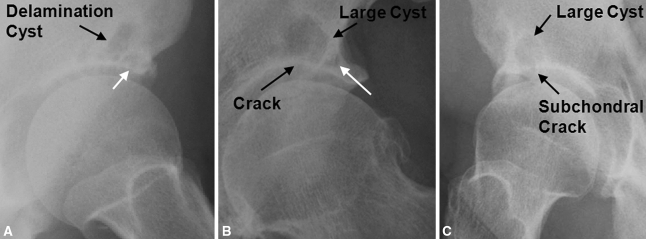

A delamination cyst was defined as a cyst located in the anterolateral portion of the acetabulum either seen directly adjacent and medial to a lateral acetabular cyst (Fig. 1A–B) or as an isolated larger cyst with an associated crack in the acetabular subchondral bone (Fig. 1C). The diameters of all acetabular cysts were measured and corrected for magnification of the radiograph using a radiograph magnification marker (Zimmer, Inc, Warsaw, IN).

Fig. 1A–C.

(A) A frog lateral radiograph of the hip shows an example of an adjacent type of delamination cyst. The delamination cyst is located directly adjacent and medial to a lateral acetabular cyst (white arrow). (B) An AP radiograph of the hip shows an example of an adjacent type of delamination cyst (white arrow denotes the adjacent lateral acetabular cyst) with an associated crack in the acetabular subchondral bone. The crack extends from the hip into the cyst. (C) This frog lateral radiograph of the hip shows an example of a cracked type of delamination cyst. The delamination cyst is a large, isolated cyst with an associated crack in the acetabular subchondral bone extending from the hip into the cyst.

We (MG) evaluated the preoperative radiographs for the presence of acetabular dysplasia by measuring the center-edge angle and acetabular index, acetabular retroversion by identifying a crossover sign, or femoroacetabular impingement characterized by a flake of bone at the lateral edge of the acetabulum or by an os acetabulum [18, 27, 41]. We evaluated the subchondral bone in the anterolateral region of the acetabulum to determine if it appeared normal, appeared irregular because it was not smooth and/or was thinner than the adjacent subchondral bone, or had a crack through it extending into the joint. In each case, we evaluated the preoperative radiographs for abnormalities of the femur associated with femoroacetabular impingement [16, 18]. In particular, we assessed all radiographs to determine if a pistol grip deformity was present and, if so, to quantify its severity by determining the degree of slip on the frog lateral view [26]. The degree of slip was classified as mild if it was less than 33%, moderate if it was 33% to 50%, and severe if it was greater than 50% [25]. We also assessed all radiographic views for the presence of osteophytes, sclerosis, and subchondral cysts of the femoral neck, particularly anteriorly. These femoral neck changes were believed indicative of hip impingement and were correlated with the presence or absence of acetabular cartilage delamination at the time of hip arthroscopy [18, 45]. All osteoarthritic changes were evaluated using the Tönnis classification [46].

In each case, we confirmed the arthroscopic findings noted in the prospective surgical database from the patients’ operative reports and intraoperative photographs. We thereby identified all the patients with labral tears and concomitant acetabular cartilage delamination at the acetabular-labral junction. Cartilage delamination was defined as the acetabular articular cartilage being present but either obviously detached from the underlying subchondral bone or easily lifted off the underlying bone with an arthroscopy probe (Figs. 2, 3). Exposed subchondral bone without an overlying cartilaginous flap was considered an arthritic change and not delamination.

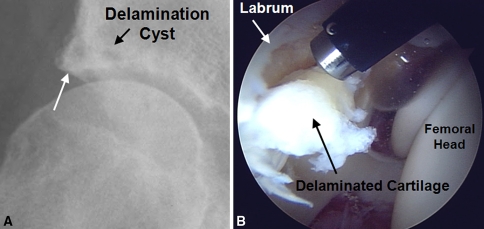

Fig. 2A–B.

(A) A preoperative AP radiograph shows the hip of a 48-year-old man with an adjacent type delamination cyst (white arrow denotes the adjacent lateral acetabular cyst). (B) During his hip arthroscopy, a radiofrequency ablator was used as a probe to show delamination of the acetabular articular cartilage adjacent to the labral acetabular junction. The edge of the labral tear can be seen overhanging the edge of the delaminated cartilage.

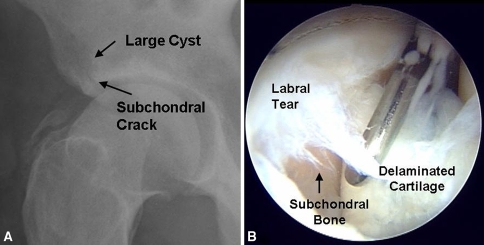

Fig. 3A–B.

(A) A preoperative frog lateral radiograph shows the hip of a 32-year-old man with a cracked type delamination cyst. The cyst is an isolated large cyst with a crack in the subchondral bone that extends into the hip. (B) An intraoperative photograph of the same patient at the time of his hip arthroscopy shows a partial-thickness labral tear at the acetabular-labral junction. The arthroscopic probe shows the adjacent articular cartilage is delaminated from the underlying subchondral bone.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of the presence of a delamination cyst were determined using preoperative radiographs of patients with a labral tear of the hip to predict acetabular cartilage delamination at the time of arthroscopy. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Nineteen of the 125 hips (19 patients) who underwent hip arthroscopy for a labral tear had either a delamination cyst on the preoperative radiographs or had delamination of the acetabular articular cartilage at the time of hip arthroscopy. There were 14 men and five women ranging in age from 29 to 56 years (mean, 41 years). The right hip was affected in 13 patients and the left in six. The average duration of symptoms before arthroscopy was 45 months (range, 8–144 months). The labral tear was the result of major trauma in three patients, had an acute onset in six patients, and was insidious in onset in 10 patients. Mechanical symptoms were present in eight of the patients.

At arthroscopy, 15 of the 19 hips (12% of the 125 hips) had a tear of the labrum and delamination of the acetabular articular cartilage (Figs. 2, 3); that is, four of the hips had a delamination cyst but no cartilage delamination. In all cases, the labral tear was a partial-thickness tear of the anterior labrum at the acetabular-labral junction and there was delamination of the adjacent acetabular articular cartilage (Figs. 2, 3). Overall, 47 of 125 hips (38%) had a lateral acetabular cyst. We identified a delamination cyst on the radiographs of 16 of the 125 hips (13%) with 11 having the adjacent cyst type and five having the cracked cyst type. Four of the 12 hips with adjacent cysts also had a crack in the acetabular subchondral bone (Fig. 1B).

All delamination cysts were located in the anterosuperior region of the acetabulum and were identified on the AP and the frog lateral hip radiographs in 13 hips, on the frog lateral view in two of the hips, and on the AP view in one of the hips.

The diameter of the delamination cysts varied from 3 to 28 mm and had a mean diameter of 10 mm. The size of the cyst varied depending on the type, with adjacent cysts ranging from 3 to 14 mm (mean, 7 mm), adjacent cysts with a crack in the acetabular subchondral bone from 14 to 20 mm (mean, 17 mm), and cracked cysts from 15 to 28 mm (mean, 18 mm). The lateral acetabular cysts, which were present on the preoperative radiographs in 14 of the 19 hips, generally were smaller and ranged in diameter from 2 to 5 mm (mean, 3 mm) (Fig. 2).

We identified numerous associated radiographic findings. The preoperative radiographs showed a pistol grip deformity in 14 of the 15 hips with acetabular cartilage delamination. The degree of slip was mild in seven and moderate in seven of the hips. An anterior femoral neck osteophyte was identified in eight hips and six of the hips had flake of bone at the lateral edge of the acetabulum. Five hips had a retroverted acetabulum and two had mild acetabular dysplasia with a normal center-edge angle but an acetabular index of zero. No hips had normal femoral and acetabular anatomy. The subchondral bone in the anterolateral region of the acetabulum had a crack in nine hips, was irregular in seven hips, and normal in the remaining two hips. Arthritic changes were identified on the preoperative radiographs of six hips. Three hips had subchondral sclerosis (Tönnis Grade 1), two had partial cartilage interval narrowing (Tönnis Grade 2), and one had severe localized joint space narrowing (Tönnis Grade 3).

When we compared the radiographic evaluation and arthroscopic findings, there were four patients with delamination cysts who did not have articular cartilage delamination at the time of arthroscopy (false-positives) and three patients with no delamination cysts who had articular cartilage delamination at the time of arthroscopy (false-negatives). Therefore, in patients with a labral tear of the hip, using the presence of a delamination cyst on a preoperative radiograph to predict acetabular cartilage delamination resulted in a sensitivity of 80%, a specificity of 96.3%, a PPV of 75%, and a NPV of 97.2% (p = 0.04). Of the four hips with false-positive results (ie, a delamination cyst but no articular cartilage delamination), hip arthroscopy revealed a labral tear and normal acetabular articular cartilage in two hips. The other two patients were 45- and 62-year-old women who presented with a 1- and 2-year history, respectively, of hip pain and mechanical symptoms. Both hips had radiographic evidence of impingement, with one hip having a retroverted acetabulum and the other a pistol grip deformity with an anterior neck osteophyte. Their preoperative radiographs revealed only mild arthritic changes with subchondral sclerosis (Tönnis Grade 1). At arthroscopy, the articular cartilage adjacent to the labral tear was not delaminated, but there was a large, localized region where the acetabular cartilage was completely denuded thereby exposing the underlying subchondral bone. Both of these patients underwent hip arthroplasty within 2 years of their hip arthroscopy because of increasing pain and progressive arthritic changes on their radiographs. In two of the three patients with false-negative results, those who had acetabular cartilage delamination at the time of arthroscopy but no preoperative delamination cysts, their labral tears were a direct result of a major traumatic injury and not the result of long-standing injury or overload to the labrum and hip. Excluding patients who had major trauma as the etiology of their labral tear, 99 hips had labral tears with either an acute or insidious onset. In this subgroup, there were three false-positives and one false-negative, but at arthroscopy, two of the three patients with false-positives had a large, localized region where the acetabular cartilage was completely denuded from the underlying subchondral bone. In patients with labral tears secondary to nontraumatic etiology, the presence of a delamination cyst on a preoperative radiograph predicted acetabular cartilage delamination with a sensitivity of 92.3%, a specificity of 96.6%, a PPV of 80%, and NPV of 98.8% (p = 0.03).

Discussion

The status of the articular cartilage adjacent to a labral tear of the hip is a major determinant of the patient’s outcome, and preoperative knowledge of the status of this cartilage is critical for appropriate surgical decision making and for counseling patients regarding their prognosis and recovery [6, 10, 17, 30, 31, 34, 42]. We identified patients who underwent hip arthroscopy for a labral tear and had delamination of the articular cartilage and then correlated the delamination with the presence of a previously undescribed finding on the preoperative plain radiographs, a delamination cyst.

Limitations of the study are that we do not have sequential radiographs and MR images of the patients, therefore, we do not know how much time is required after articular cartilage delamination before the delamination cyst becomes apparent on the plain radiographs. Most of the patients in this study were seen long after onset of their hip pain. Patients presenting with labral tears shortly after their onset may not have had sufficient time to allow the delamination cyst to develop.

Nonetheless, we have clearly established, in patients with a labral tear of the hip, the preoperative radiographic appearance of a delamination cyst in the anterosuperior portion of the acetabulum is highly predictive of concomitant acetabular cartilage delamination. This association is even more evident in patients who have a labral tear not caused by major trauma such as a violent impact or dislocation. A delamination cyst is best detected on the AP or frog lateral radiograph of the hip as either a cyst located directly adjacent and medial to a lateral acetabular cyst or as a larger cyst with an associated crack in the acetabular subchondral bone.

Preoperative studies have been relatively ineffective at showing articular cartilage injuries. This is particularly important clinically as as many as ½ to 2/3 of all labral tears seen during hip arthroscopy have associated articular cartilage damage, and it is the extent of this associated injury that is often the limiting determinant on the outcome of arthroscopic labral débridement [5, 6, 28, 30, 31, 42]. MRI arthrograms are accurate for preoperatively detecting labral lesions, but they have limitations in detecting associated acetabular cartilage delamination [5, 7, 15, 23, 43]. Investigators of several studies suggest arthritic changes or acetabular cartilage loss can be identified by preoperative MRI, but these studies do not specifically address cartilage delamination or nonarthritic cartilage injuries. Mintz et al. [32] did a retrospective review of 92 patients who underwent MRI of the hip and subsequent hip arthroscopy to evaluate the ability of noncontrast MRI with a small pixel size to identify arthritic changes of the acetabulum. Overall, normal cartilage could be differentiated from abnormal cartilage with a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 80%. Kassarjian et al. [22] retrospectively reviewed the MRI arthrograms and surgical findings in 11 hips that underwent surgical treatment for femoroacetabular impingement and were able to correctly identify cartilage loss in 10 of these hips. Schmid et al. [43] retrospectively reviewed 42 hips in which they correlated cartilage lesions seen on MRI arthrography with intraoperative findings. On average, the sensitivities and specificities of MRI arthrographic detection of cartilage damage was only 64% and 80%, respectively, and there was poor interobserver agreement. Schmid et al. [43] did not specifically report on cartilage delamination. Duffy et al. [15] compared the diagnosis from the MRI arthrogram with the findings at arthroscopy in 15 patients and reported the MRI arthrogram was particularly inaccurate when assessing for articular cartilage defects. Only Beaulé et al. [1] were able to identify acetabular cartilage delamination noninvasively. They reported on four consecutive patients who had delamination of the acetabular cartilage observed on MRI arthrography with gadolinium, which subsequently was confirmed at the time of surgical dislocation of the hip. However, this was a report on four cases and does not address the sensitivity and specificity of this diagnostic tool. In their study, for patients with labral tears secondary to a nontraumatic etiology, the presence of a delamination cyst on a preoperative radiograph predicted acetabular cartilage delamination with a sensitivity of 93.3%, a specificity of 96.6%, a PPV of 80%, and NPV of 98.8%.

The delamination cysts we identified on radiography are likely the result of shearing off or delamination of the acetabular articular cartilage, allowing access of the intraarticular joint fluid to the underlying subchondral bone. The anterosuperior location of the delaminated articular cartilage and the delamination cysts correlates with the location of damage to the hip previously reported for cam-type femoroacetabular impingement [18, 19, 21, 29, 33, 35, 45]. This region of the acetabulum is best seen on the frog lateral view of the hip and explains why the delamination cyst was seen on this view in 92% of the cases. Radiographic findings of cam-type femoroacetabular impingement were seen in 93% of our patients with cartilage delamination. It is reasonable to speculate, if the impingement is repetitive and prolonged, the subchondral bone under the delaminated articular cartilage will continue to be impacted by the femoral head/neck region and can result in a microfracture of this region. This would allow the intraarticular fluid to be pumped from the joint into the surrounding bone, thereby creating a delamination cyst. The actual crack in the subchondral bone was observed on the preoperative radiograph in 50% of the cases. In this study, the patients presented an average of 45 months after the onset of symptoms from their labral tears, indicating their hips were exposed to continued impingement for an extended period after onset of the labral tears. At what time the delamination cyst became apparent on the plain radiograph is unknown because these patients were not seen at the onset of their hip pain or radiographed sequentially. Labral tears occurring from a major traumatic event such as a motor vehicle accident are infrequent, are sudden in onset, and usually occur in normal joints [3, 6, 45]. Unless the major trauma is associated with a fracture of the acetabulum, the nonrepetitive nature of the injury likely would preclude the exposed subchondral surface from fracturing and allowing seepage of the articular fluid into the acetabular bone. As a result, labral tears with delamination or shearing off of the acetabular articular cartilage, secondary to major trauma, should not be expected to be associated with a delamination cyst. This would explain why two of the three false-negatives were in hips that had experienced a major traumatic event and why the sensitivity of delamination cysts in predicting cartilage delamination increased from 80% to 93% in patients with labral tears secondary to a nontraumatic etiology.

Although the preoperative radiographic appearance of a delamination cyst was not predictive of cartilage delamination in the four hips that were false-positives, in two of these hips, it was still predictive of considerable damage to that adjacent acetabular cartilage. Both hips had radiographic evidence of femoroacetabular impingement and had exposed subchondral bone denuded of articular cartilage at the time of arthroscopy. Whether these two hips initially had acetabular cartilage delamination that progressed to frank acetabular arthritis by the time the hips underwent arthroscopy is uncertain. Nonetheless, the delamination cyst in these two cases correctly indicated a serious injury to the acetabular articular cartilage adjacent to the labral tear.

Knowing the status of the acetabular articular cartilage adjacent to the labral tear preoperatively is essential for appropriate surgical decision making and for counseling patients regarding their prognosis and recovery. Hip arthroscopy is useful in the treatment of labral tears, but labral excision alone does not completely resolve hip pain in patients with concomitant cartilage injury, with success rates of only 21% reported [5, 17, 35, 42]. Microfracture of the acetabulum or acetabular rim resection can be performed in conjunction with the arthroscopy, but in either case the chondral delamination will alter the prognosis and postoperative rehabilitation protocol [6, 8, 11, 28, 32, 39, 40, 42]. An open femoroacetabular osteoplasty with resection of as much as 1 cm of the rim of the acetabulum to remove the site of chondral delamination can be planned if preoperatively it is recognized the labral tear is associated with acetabular cartilage delamination [35]. Again, this procedure has different surgical risks and requires a different postoperative regime than simple hip arthroscopy for a labral tear.

A delamination cyst is a previously undescribed and novel radiographic sign that can accurately predict preoperatively which patients with labral tears have associated acetabular cartilage delamination. Results of our study show chondral delamination can be reliably inferred in these patients by the presence of a delamination cyst on plain radiographs, thereby minimizing the need to perform expensive special imaging with or without invasive infiltrations. Identifying these cysts preoperatively can aid the surgeon in selecting the appropriate surgical procedure and in predicting the prognosis and outcome of the planned surgery. Future studies with MRI to try to identify these cysts earlier at a stage when they are not seen on radiographs and the cartilage flap is smaller and less extensive may be warranted.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution has either waived or does not require approval for the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

References

- 1.Beaule PE, Zaragoza E, Copelan N. Magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium arthrography to assess acetabular cartilage delamination. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:2294–2298. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Beck M, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz R. Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage: femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1012–1018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Burnett RS, Della Rocca GJ, Prather H, Curry M, Maloney WJ, Clohisy JC. Clinical presentation of patients with tears of the acetabular labrum. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1448–1457. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Byrd JW. Labral lesions an elusive source of hip pain case reports and literature review. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:603–612. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Byrd JW. Hip arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:433–444. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Byrd JW, Jones KS. Prospective analysis of hip arthroscopy with 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:578–587. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Byrd JW, Jones KS. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical assessment, magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance arthrography, and intra-articular injection in hip arthroscopy patients. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1668–1674. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Byrd JW, Jones KS. Microfracture for grade IV chondral lesions in the hip. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(suppl 1):341.

- 9.Byrd JWT. Operative Hip Arthroscopy. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers Inc; 1998.

- 10.Clohisy JC, McClure JT. Treatment of anterior femoroacetabular impingement with combined hip arthroscopy and limited anterior decompression. Iowa Orthop J. 2005;25:164–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Crawford K, Philippon MJ, Sekiya JK, Rodkey WG, Steadman JR. Microfracture of the hip in athletes. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25:327–335. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Czerny C, Hofmann S, Neuhold A, Tschauner C, Engel A, Recht MP, Kramer J. Lesions of the acetabular labrum: accuracy of MR imaging and MR arthrograph in detection and staging. Radiology. 1996;200:225–230. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Czerny C, Hofmann S, Urban M, Tschauner C, Neuhold A, Pretterklieber M, Recht MP, Kramer J. MR arthrography of the adult acetabular capsular-labral complex: correlation with surgery and anatomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:345–349. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Dorrell JH, Catterall A. The torn acetabular labrum. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986;68:400–403. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Duffy DJ, Wall O, Macdonald DA. A comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and arthroscopic diagnosis of hip disorders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(suppl 1):73.

- 16.Espinosa N, Rothenfluh DA, Beck M, Ganz R, Leunig M. Treatment of femoro-acetabular impingement: preliminary results of labral refixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:925–935. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Farjo LA, Glick JM, Sampson TG. Hip arthroscopy for acetabular labral tears. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:132–137. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, Leunig M, Notzli H, Siebenrock KA. Femoro-acetabular impingement: an important cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;417:112–120. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Goodman DA, Feighan JE, Smith AD, Latimer B, Buly RL, Cooperman DR. Subclinical slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:1489–1497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Hofmann S, Tschauner C, Urban M, Eder T, Czerny C. Clinical and diagnostic imaging of labrum lesions in the hip joint. Orthopade. 1998;27:681–689. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Ito K, Minka MA 2nd, Leunig M, Werlen S, Ganz R. Femoro-acetabular impingement and the cam-effect: a MRI-based quantitative anatomical study of the femoral head-neck offset. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:171–176. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Kassarjian A, Yoon LS, Belzile E, Connolly SA, Millis MB, Palmer WE. Triad of MR arthrographic findings in patients with cam-type femoroacetabular impingement. Radiology. 2005;236:588–592. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Leunig M, Podeszwa D, Beck M, Werlen S, Ganz R. Magnetic resonance arthrography of labral disorders in hips with dysplasia and impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;418:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Leunig M, Werlen S, Ungersbock A, Ito K, Ganz R. Evaluation of the acetabular labrum by MR arthrography. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:230–234. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Locher S, Werlen S, Leunig M, Ganz R. MR-arthrography with radial sequences for visualization of early hip pathology not visible on plain radiographs. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 2002;140:52–57. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Loder RT, Aronsson DD, Dobbs MB, Weinstein SL. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Instr Course Lect. 2001;50:555–570. [PubMed]

- 27.Mast JW, Brunner RL, Zebrack J. Recognizing acetabular version in the radiographic presentation of hip dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;418:48–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.McCarthy JC. Hip arthroscopy: applications and technique. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3:115–122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.McCarthy JC, Noble PC, Schuck MR, Wright J, Lee J. The role of labral lesions to development of early degenerative hip disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;393:25–37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.McCarthy J, Noble P, Aluisio FV, Schuck M, Wright J, Lee JA. Anatomy, pathologic features, and treatment of acetabular labral tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;406:38–47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.McCarthy JC. The diagnosis and treatment of labral and chondral injuries. Instr Course Lect. 2004;53:573–577. [PubMed]

- 32.Mintz DN, Hooper T, Connell D, Buly R, Padgett DE, Potter HG. Magnetic resonance imaging of the hip: detection of labral and chondral abnormalities using noncontrast imaging. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:385–393. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Notzli HP, Wyss TF, Stoecklin CH, Schmid MR, Treiber K, Hodler J. The contour of the femoral head-neck junction as a predictor for the risk of anterior impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:556–560. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.O’Leary JA, Berend K, Vail TP. The relationship between diagnosis and outcome in arthroscopy of the hip. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:181–188. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Parvizi J, Leunig M, Ganz R. Femoroacetabular impingement. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:561–570. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Peelle MW, Della Rocca GJ, Maloney WJ, Curry MC, Clohisy JC. Acetabular and femoral radiographic abnormalities associated with labral tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;441:327–333. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Peters CL, Erickson JA. Treatment of femoro-acetabular impingement with surgical dislocation and débridement in young adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1735–1741. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Petersilge CA. MR arthrography for evaluation of the acetabular labrum. Skeletal Radiol. 2001;30:423–430. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Philippon MJ, Schenker ML, Briggs KK, Kuppersmith DA, Maxwell RB, Stubbs AJ. Revision hip arthroscopy. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1918–1921. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Philippon MJ, Schenker ML, Briggs KK, Maxwell RB. Can microfracture produce repair tissue in acetabular chondral defects? Arthroscopy. 2008;24:46–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Reynolds D, Lucas J, Klaue K. Retroversion of the acetabulum: a cause of hip pain. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:281–288. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Santori N, Villar RN. Acetabular labral tears: results of arthroscopic partial limbectomy. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:11–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Schmid MR, Notzli HP, Zanetti M, Wyss TF, Hodler J. Cartilage lesions in the hip: diagnostic effectiveness of MR arthrography. Radiology. 2003;226:382–386. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Schnarkowski P, Steinback LS, Tirman PF, Peterfy CG, Genant HK. Magnetic resonance imaging of labral cysts of the hip. Skeletal Radiol. 1996;25:733–737. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Tanzer M, Noiseux N. Osseous abnormalities and early osteoarthritis: the role of hip impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;429:170–177. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Tonnis D, Heinecke A. Current concepts review. Acetabular and femoral anteversion: relationship with osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1747–1770. [DOI] [PubMed]