Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Research on nicotine and attention has mainly utilized samples of deprived smokers and tasks requiring volitional responses, raising the question of whether nicotine improves attention or simply alleviates withdrawal or improves motor speed. This study used the startle eyeblink reflex to assess nicotine effects on auditory attention in non-smokers.

Method

Sixty-seven healthy young adult non-smokers completed a tone discrimination task. Acoustic startle probes were presented 60, 120, 240, or 4500 ms after onset of 2/3 of the tones and during intertrial intervals. Attention was assessed via 1) short-lead prepulse inhibition (PPI) of startle, a measure of early filtering; 2) long-lead prepulse facilitation (PPF) of startle, a measure of sustained processing, and 3) the modification of PPI and PPF by focused attention. Participants completed two lab sessions, once while wearing a 7 mg transdermal nicotine patch, and once while wearing a placebo patch. Patches were administered in a double-blind procedure.

Results

Nicotine increased overall PPI, ηp2 = .09. Attention increased long-lead PPF ηp2 = .25, but not short-lead PPI. Nicotine did not reliably enhance early or late controlled attentional processing in the sample overall. However, correlational analyses demonstrated that nicotine most improved attentional modification of short-lead PPI among participants with the weakest early attentional processing under placebo conditions.

Conclusions

Nicotine enhanced early attentional filtering in general, and the effects of nicotine on early, focused attention were dependent upon individual differences in placebo levels of attentional processing. The present data suggest the effects of nicotine on attention extend beyond the alleviation of withdrawal and simple motor speeding.

Keywords: Attention, nicotine, prepulse inhibition, prepulse facilitation, automatic filtering, focused attention, individual differences, startle, non-smokers, smoking

The effects of nicotine on attention have been the focus of considerable empirical research (e.g., Kassel, 1997; Levin et al., 2006; Newhouse et al., 2004). Although there are exceptions, nicotine administered via smoking, gum, and transdermal patch generally increases sustained, divided, and focused attention among abstinent cigarette smokers. However, reliance on studies of deprived smokers poses a serious interpretive issue. Specifically, it is difficult to ascertain whether performance differences are due to true attention-enhancing effects of nicotine, withdrawal relief, or alleviation of a pre-existing attentional deficit that smoking self-medicates (Gilbert & Gilbert, 1995; Kassel, 1997). Recent research addresses this problem by either comparing non-smoking controls to smokers or by administering nicotine to non-smokers.

In non-smokers, the literature on nicotine and attention is smaller and more equivocal. Transdermal nicotine generally improves sustained attention measured via continuous performance tests (CPT; Levin et al., 2001; Levin et al., 1998). Only one study has examined nicotine's effect on divided attention in non-smokers (Hindmarch et al., 1990); though nicotine gum did not improve performance, the null findings may be related to the difficulty of regulating nicotine levels via gum. Results of studies of focused attention in non-smokers are also mixed. For example, in research on the Stroop task, performance improved with nicotine gum (Provost & Woodward, 1991) but not in a study using subcutaneous nicotine (Foulds et al., 1996).

The modest and inconsistent findings in non-smokers suggest that either nicotine has little effect beyond alleviation of withdrawal or there are important moderators at work. Among candidate moderators, the nature of the subject sample may be particularly critical. Specifically, Newhouse et al. (2004) propose that the beneficial effects of nicotine on attention are inversely related to baseline attentional functioning, with greatest benefit to persons with very poor baseline (or placebo) attention and actual impairment of attention among persons with maximal baseline performance. The findings of Poltavski and Petros (2006), in which nicotine improved CPT target/non-target discrimination measures in non-smokers only among those participants with relatively poor levels of self-reported attention, is consistent with this perspective. Thus, it seems important to consider baseline attentional performance in studies of non-smokers.

There are other limits on the non-smoker literature. The primary dependent variable has been reaction time (RT). However, improvement in RT with nicotine could reflect effects on motor performance rather than attention (Heishman et al., 1994). In addition, whereas many studies have assessed visual attention, few have assessed attention to auditory stimuli. In sum, expanding the work on nicotine and attention into the auditory modality, using a task that is less dependent on voluntary motor responses (i.e., RT), and greater consideration of individual difference moderators, may improve our understanding of nicotine effects on attention. Startle eyeblink modification allows assessment of automatic early filtering and sustained processing, as well as the modulation of these processes by controlled (focused) attention (Filion et al., 1998).

The eyeblink startle response, a reflex elicited by intense stimuli with abrupt onset (e.g., a loud noise burst), occurs involuntarily, is slow to habituate, and is sensitive to attentional processing in both rats and humans. Startle eyeblink magnitude is reduced when a weak, non-startling stimulus is presented 60-500 ms before the onset of the startling stimulus (Hoffman & Ison, 1980). This short-lead prepulse inhibition (PPI) is thought to reflect a partially automatic filtering or gating process, in which the processing of the prepulse is protected from disruption by attenuating the processing of subsequent stimuli (Braff & Geyer, 1990; Graham et al., 1975). Nicotine enhances PPI in rats (e.g. Acri et al., 1991), human smokers (e.g., Duncan et al., 2001; Kumari et al., 1996), and non-smokers (Kumari et al., 1997; Postma et al., 2006), suggesting that nicotine enhances fairly low-level, automatic attentional gating or filtering.

In addition to assessing relatively automatic attentional gating, startle is sensitive to controlled attentional processes. When the prepulse is the focus of active attention, short-lead PPI is enhanced (e.g., Filion et al., 1993; Jennings et al., 1996; Hawk et al., 2002). Attentional modification of PPI is often assessed within a tone discrimination paradigm in which tones serve as auditory prepulse stimuli. Participants attend to tones of one pitch and ignore tones of another pitch. Startle probes are presented at various tone-probe SOAs. Attentional modification, greater PPI during the attended tone than during the ignored tone, is most robust at an SOA of 120-ms.

Startle eyeblink magnitude is also sensitive to sustained attention. When the prepulse-probe SOA is greater than 800 ms, startle magnitude is generally larger compared to trials when there is no prepulse (e.g., Graham et al., 1975; Jennings et al., 1996). This long-lead prepulse facilitation (PPF) of startle is further enhanced by focused sustained attention. Thus, the tone discrimination paradigm allows examination of both automatic and controlled aspects of early and late focused attention (Filion et al., 1998). That attentional modification of PPI is enhanced by the stimulant methylphenidate among children with ADHD (Hawk et al., 2003) suggests the paradigm is sensitive to acute drug effects on attention.

To date, only one study has assessed the effects of smoking on attentional modification of PPI (Rissling et al., 2007). During a visual CPT short-lead PPI was disrupted by smoking abstinence compared to both a smoking condition and to a non-smoking control group. No abstinence or group effects were found for late-lead attentional modification. This study suggests that smoking either alleviates an abstinence-induced disruption of early focused visual attention or ameliorates a deficit in such processing among smokers.

Building on Rissling et al. (2007), the current study examined the effects of transdermal nicotine on attentional modification of short-lead PPI and long-lead PPF among non-smokers.1 Several hypotheses were tested. First, to the extent that nicotine increases relatively automatic filtering of stimuli, short-lead PPI should be enhanced by nicotine compared to placebo. Second, to the extent that nicotine enhances focused attention, we hypothesized that the increase in short-lead PPI (i.e., 120-ms SOA) and long-lead PPF (the 4500-ms SOA) during attended compared to ignored tones would be augmented during the nicotine session vs. the placebo session. Third, we predicted that nicotine would have the greatest effect among participants with the lowest levels of attentional modification during the placebo condition (see Newhouse et al., 2004).

Method

Participants

Participants were screened for nicotine use during a mass testing for a Psychology 101 course. Undergraduate non-smokers who denied nicotine use in the past year but reported modest lifetime exposure (between 1 puff and 100 cigarettes; CDC, 2002) were recruited.2 Phone screenings confirmed nicotine status and screened for health conditions that contraindicated nicotine administration. Participants earned course credit. Of the 111 participants recruited, 13 failed to return for Session 2 and 3 participants (all in the nicotine patch condition) withdrew from the study due to nausea, leaving 95 participants who completed both sessions. Twenty-eight participants were excluded due to outlying PPI data (n=21; see data reduction) or failure to correctly perform the task (n=7; i.e., multiple false alarms to the ‘to be ignored’ tone). The final sample of 67 participants (32 female) was predominantly Caucasian (67%), with 4% African American, 7% Asian/Asian-American, 9% Latino/Hispanic, and 3% other.

Measures and Apparatus

Nausea ratings

To assess nausea, both as a manipulation check of the effects of nicotine and to rule out extreme nausea as a possible confound, participants completed a computerized visual analog scale (presented via MediaLab® software).

Auditory stimuli

Prepulse tones and startle probes were presented with VPM software (Cook et al., 1987) via a Soundblaster 64 AWE Gold sound card and matched Telephonics TDH49-P headphones. Prepulses were 5- and 7-s tones, 800 and 1200 Hz, presented at 70 dB (25 ms rise/fall). Startle probes were 50-ms, 100-dB bursts of white noise.

Psychophysiological measures

Startle eyeblink EMG was measured from bilateral orbicularis oculi using miniature Ag/AgCl electrodes, as in our recent work (Ashare et al., 2007; Hawk et al., 2002, 2003). The amplified EMG signal (10-500 Hz) was sampled at 1000 Hz from 50 ms before to 300 ms following each startle probe onset. Heart rate was assessed as a manipulation check, as nicotine increases HR (e.g., Najem et al., 2006), via EKG from two Ag/AgCl electrodes attached in a modified lead II configuration. The amplified EKG signal was filtered (3-35 Hz) and R-waves were detected via a Schmitt trigger. A ground electrode was placed on the forearm.

Nicotine Patches

Habitrol® 7 mg (Novartis, New Jersey, USA) patches were used because this brand offers a slow-rise nicotine transfer rate (Benowitz, 1993), with blood nicotine levels reaching about 50% of peak within 4 hours. This is important to minimize the nausea associated with the use of fast-rise nicotine patches in non-smokers (Gilbert et al., 2003). Placebo patches were manufactured by SmithKline Beecham.

Procedure

All procedures were approved by the University at Buffalo Health Sciences IRB. The two lab sessions were separated by one week. Procedures for both days were identical except that informed consent was obtained at the beginning of Session 1 and debriefing was conducted at the end of Session 2. Patches were applied to the upper arm and covered with a bandage. Participants were informed of possible side effects and given emergency contact information. Baseline subjective effects (e.g., nausea) were assessed (other subjective effects are the focus of a separate report), and the participants left the lab, returning four hours later for the tone task session.

A different research assistant, unaware of patch condition, ran the remaining portion of the experiment. Upon returning to the lab, the participants completed subjective ratings a second time. Electrodes were then attached for assessment of bilateral eyeblink and EKG, and sample prepulse tones were presented to ensure discrimination of tone pitch. Next, the participants were given instructions for the tone task. For example:

…You will begin to hear a series of tones… Most of the tones, like the ones you heard earlier, are 5 s long. However, some of the tones will be longer-than-usual…7 s long.

…Press the trigger button whenever you hear a longer-than-usual LOW tone. So, you need to pay attention to only the LOW tones. You can ignore the HIGH tones…

A single probe-alone habituation trial preceded the 48-trial tone discrimination task. Half of the tones were of each pitch. Startle probes were presented during two-thirds of the tones of each pitch at SOAs of 60, 120, 240, and 4500 ms. Two-thirds of tones of each pitch were of 5 s duration; the remaining tones were of 7 s duration, and tones were separated by an average inter-trial interval (ITI) of 30 s. One-sixth of the ITIs contained startle probes. Each participant received one of eight pseudorandom tone orders.

Data Reduction and Analysis

Three participants were missing heart rate data and two were missing complete self-report data. Nausea rating was analyzed via a 2 Sex × 2 Patch Order (nicotine first vs. placebo first) × 2 Patch Condition (nicotine vs. placebo patch) × 3 Assessment Time (pre-patch [Hour 0], pre-task [Hour 4], post-task [Hour 5]) ANOVA. Planned contrasts compared Hour 0 vs. 4 and Hour 4 vs. 5. Mean HR was computed from EKG interbeat interval (Graham, 1978) for the ITI period on no-startle trials and analyzed in a 2 Sex × 2 Patch Order × 2 Patch Condition ANOVA.

Eyeblink startle responses were rectified, low-pass filtered (80-ms time constant), and scored with the program of Balaban et al. (1986). Startle responses had onsets of 21-120 ms and were excluded for excessive baseline EMG variability (see Hawk et al., 2002, 2003), resulting in exclusion of 10.6% of right and 11.5% of left eyeblink trials. Participant averages were computed for eyeblink data for each 2 Patch (nicotine vs. placebo) × 4 SOA (60, 120, 240, 4500 ms) × 2 Attend (attend vs. ignore) condition, as well as for probe-alone startle trials for each eye.

Percent prepulse modification was computed as: ([Mprepulse − MITI)/(MITI)] × 100). Percentages greater than 1.5 IQRs above the 75th percentile on each SOA were considered outliers. For participants with no outlying values (n=61), data were aggregated across eyes. For participants with outliers at only one eye (n=13), data for the other eye were retained. If data for both eyes contained outliers (n=21), then the participant was excluded.3

Probe-alone startle magnitude was analyzed with a 2 Sex × 2 Patch Order × 2 Patch Condition ANOVA. Patch order (nicotine vs. placebo first) and sex were between-subjects factors; Sex × Patch Order interactions were not included in any analysis in order to maintain focus on effects of interest. Patch condition (nicotine vs. placebo) was a within-subject factor.

Separate ANOVAs assessed short-lead PPI and long-lead PPF. For both PPI and PPF, Attend (attended vs. ignored pitch) was a within-subjects factor. For PPI, planned orthogonal contrasts assessed differences between the 60- and 240-ms SOAs (SOA linear) and between 120 ms and the average of 60 and 240 ms (SOA quadratic), as in prior work (e.g., Hawk et al., 2002).

Correlation analyses tested whether nicotine effects were most robust among participants with low levels of attentional modification during the placebo condition (Hypothesis 3). First, the increase in attentional modification during nicotine session minus attentional modification during placebo session was correlated with the amount of attentional modification during placebo session (rp,n-p). Because error of measurement in the placebo session contributes to both indices (placebo and the change score), such correlations are biased by regression toward the mean (RTM). Following Tu and Gilthorpe (2007), we employed Oldham's (1962) method to address the issue. This involves testing the correlation between change from placebo to nicotine with the mean of placebo and nicotine responses (rmean(p,n),n-p), two indices which are not biased in their association. This is a test of the extent to which variance is reduced in the nicotine compared to the placebo condition – unless the experimental manipulation reduces variance, the correlation is 0. To the extent that the correlation is large, there is a true relationship that goes beyond RTM.

Results

Manipulation Checks

Nausea

Nausea ratings did not differ between pre-patch (Hour 0) and pre-task (Hour 4) conditions, F < 1. However, nausea increased over the course of the attention task during the nicotine session, F (1,61) = 4.2, p < .05 (M [SE]: Hour 4 = 7.3 [1.6], Hour 5 = 13.0 [3.0]), but not the placebo session, F < 1, (M [SE]: Hour 4 = 9.3 [2.4], Hour 5 = 8.4 [2.3]), Patch × Time F (1,61) = 5.2, p < .03, ηp2 = .08. Overall levels of nausea (100-point VAS) were relatively low.4

Heart Rate

As expected, heart rate was generally higher during the ITIs of the nicotine session compared to placebo session, F(1,62) = 13.6, p < .001, ηp2 = .18 (M [SE]: nicotine = 79.1 [1.3], placebo = 75.6 [1.2]). Sex and patch order did not moderate this effect, Fs < 1.

Tone Prepulse Task

Performance Data

Overall task performance was good, with near-perfect hits (there were 8 targets) and few false alarms (M [SE] hits: session 1 = 7.4 [.15], session 2 = 7.6 [.08]; M [SE] false alarms: session 1 = 3.3 [.45], session 2 = 1.0 [.24]), and no effect of nicotine on either, Fs (1,63) < 2.1, ps > .14. A significant Patch × Patch Order interaction on false alarms, F (1, 65) = 42.8, p < .001, simply reflected a decrease in false alarms from Session 1 to Session 2.

Probe-Alone Startle

Participants who received nicotine patch during the first session showed reliable habituation of startle magnitude across sessions (M [SE]: session 1 = 11.3 μV [2.0], session 2 = 9.2 μV [1.6]), F (1,64) = 8.3, p <.01, whereas those who wore the nicotine patch during the second session did not (M [SE]: session 1 = 10.1 μV [2.0], session 2 = 10.9 μV [1.7]), F (1,64) = 1.0, p =.32, Patch × Patch Order, F (1,64) = 7.5, p <.01, ηp2 = .11, suggesting nicotine either increased overall startle magnitude or decreased between-session habituation.5

Short-lead PPI

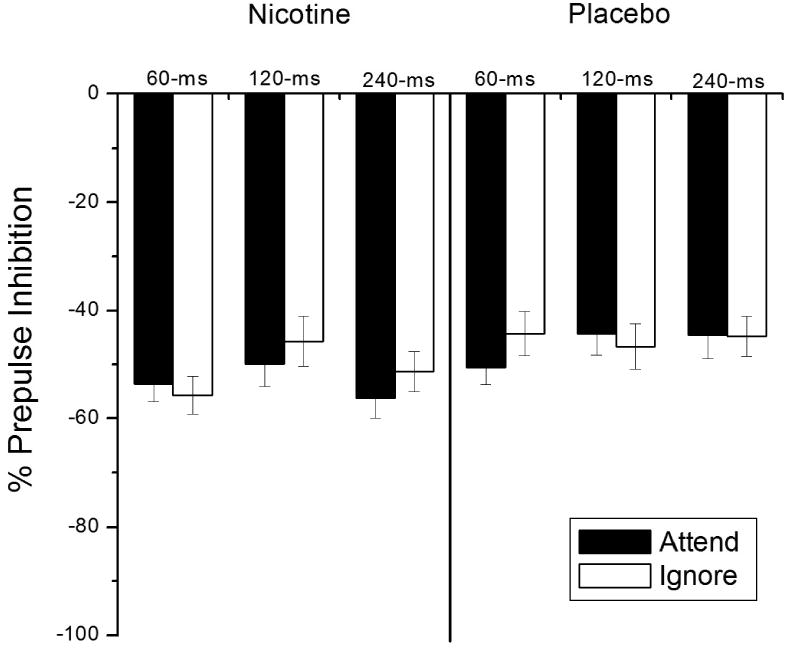

Figure 1 presents short-lead PPI data for all Patch × SOA × Attend conditions. As hypothesized, nicotine generally increased PPI compared to placebo, F (1, 64) = 5.9, p < .02, ηp2 = .09 (M [SE]: nicotine = -52.2 [3.0] placebo = -45.7 [2.8]). As in Kumari et al. (1997), this relationship was not significantly moderated by SOA, nor was it moderated by sex, or patch order, Patch × SOA, Patch × Sex, and Patch × Patch Order F's < 2.6, ps > .11.

Figure 1.

Mean percent short-lead prepulse inhibition for each Patch Condition × SOA × Attend condition. Error bars represent standard error. Patch Condition main effect, F (1, 64) = 5.9, p < .02; Patch Condition × SOA linear × Attend linear interaction F (1,64) = 5.6, p < .03.

Attentional modification of PPI effect was not replicated, attend and Attend × SOA Fs < 1. Moreover, the hypothesized enhancement of attentional modification with nicotine at the 120-ms SOA was not reliable, Patch × SOA quadratic × Attend F (1, 64) = 1.73, p = .19. Attentional modification tended to increase from the 60- to 240-ms SOA in the nicotine condition but not the placebo condition, Patch × SOA linear × Attend F (1,64) = 5.6, p < .03, ηp2 = .08, but attentional modification at the 240-ms SOA in the nicotine condition was still not reliable, p = .12.

Consistent with the individual differences hypothesis, correlation analyses (see Table 1) suggested that less attentional modification during the placebo session was associated with a larger increase in attentional modification of PPI with nicotine for overall short-lead PPI and at each SOA. As shown in Table 1, Oldham's method to correct for the bias in the above-mentioned correlations revealed attenuated but still reliable associations.

Table 1.

Correlations assessing individual differences in the effects of nicotine on attentional modification of startle.

| Baseline/Change | Oldham's Method | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOA (ms) | rp,n-p | p< | rmean(p,n),n-p | p< |

| Short-lead | ||||

| Overall | -.825 | <.001 | -.430 | .001 |

| 60 | -.810 | <.001 | -.308 | .01 |

| 120 | -.812 | <.001 | -.225 | .07 |

| 240 | -.752 | <.001 | -.276 | .02 |

| Long-lead | ||||

| 4500 | -.698 | <.001 | -.033 | .79 |

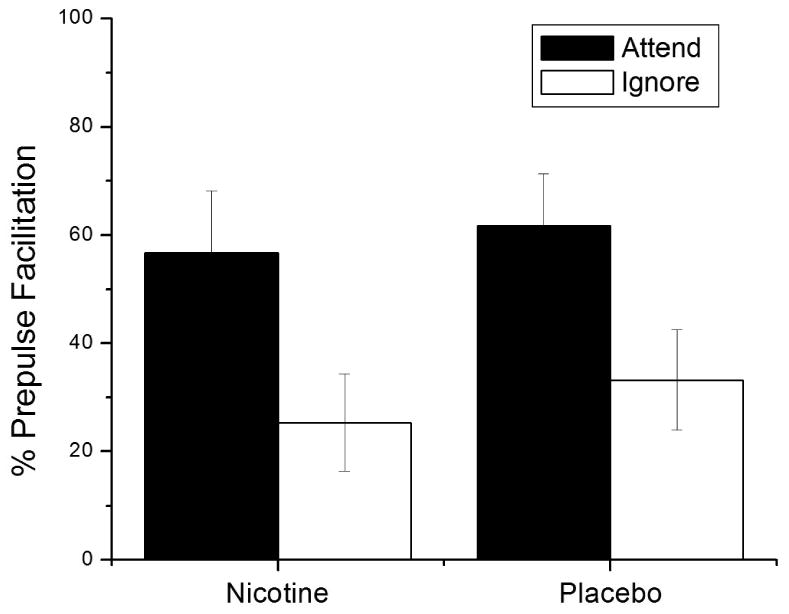

Long-lead PPF

Mean percent startle modification at the long-lead SOA (4500-ms) for each Patch × Attend condition is presented in Figure 2. As predicted, long-lead PPF was greater during attended compared to ignored tones, attend F (1,64) = 21.2, p < .001, ηp2 = .25. However, this attentional effect was not reliably enhanced by nicotine, F < 1.

Figure 2.

Mean percent long-lead prepulse facilitation for all Patch Condition × Attend conditions. Error bars represent standard error. Attend main effect, F (1,64) = 21.2, p < .001.

The correlation analysis (see Table 1) assessing the relationship between placebo and change between placebo and nicotine suggested that improvement in attentional modification from the placebo session to the nicotine session was inversely related to the amount of attentional modification during the placebo session. However, Oldham's method suggested that this relationship was completely due to RTM, as the correlation between the mean of placebo and nicotine with improvement for nicotine compared to placebo was essentially 0.

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of transdermal nicotine on attentional modification of short-lead prepulse inhibition and long-lead prepulse facilitation of the startle eyeblink reflex among non-smokers. Relatively automatic attentional filtering and the effects of controlled, focused attentional processes on this filtering were assessed by short-lead PPI at 60-ms, 120-ms, and 240-ms SOAs during attended and ignored tone prepulses. Nicotine increased overall PPI but did not increase overall attentional modification at the short-lead interval. However, correlational analyses suggested that the positive effect of nicotine on attentional modification for short-lead PPI was inversely related to levels of attentional modification during placebo. The allocation of sustained attention and the effect of directed attention on this process were assessed by measuring long-lead PPF at 4,500-ms SOA during attended and ignored prepulses. Though overall late-lead facilitation was greater during attended compared to ignored prepulses, nicotine did not enhance this effect overall nor did individual differences in placebo modification reliably moderate the effects of nicotine on this sustained attentional processing.

Early Filtering and Focused Attention

As predicted, nicotine reliably increased overall short-lead PPI compared to placebo. This is the first study to report the finding with continuous auditory lead stimuli, and these results replicate and extend previous findings that nicotine increases PPI using discrete passive prepulses in smokers (e.g., Duncan et al., 2001; Kumari et al., 1996) and non-smokers (Kumari et al., 1997). Considering the existent literature and the current study, the increase of PPI by nicotine suggests that one way nicotine may improve attention is by enhancing stimulus filtering. This filtering process is a relatively automatic process that requires little, if any, conscious effort and allows the individual to screen out distracting stimuli.

In order to assess the effects of controlled, focused attention on early attentional filtering, participants discriminated between relevant and irrelevant stimuli. Short-lead PPI is typically greater during attended compared to ignored tones, particularly at the 120-ms SOA (e.g., Dawson et al., 1993; Hawk et al., 2002), however, the current study failed to replicate this finding. This failure was not due to poor task performance, and the expected effect of directed attention was found at the long-lead interval (discussed below), suggesting that participants were actively deploying their attention to to-be-attended stimuli. However, one possibility is that the button press for targets, because it eliminated a working memory demand (i.e., maintaining cumulative number of targets) relative to the typical paradigm, resulted in a task that did not sufficiently tax cognitive resources to result in attentional modification early in stimulus processing. Consistent with this interpretation, although we recently obtained attentional modification of short-lead PPI using the button press (Ashare et al., 2007), we did not observe the effect in our pilot work until we increased the task difficulty by making the duration harder to discriminate (except in children, Hawk et al., 2003). Finally, in recent work with visual stimuli (Rissling et al., 2005), attentional modification of PPI was reliable in a degraded CPT, but not in a clear CPT, a finding the authors suggest indicates that attentional modification is greater when the discrimination requires “more extensive processing” (p. 444). Future work that directly manipulates task difficulty and complexity would be helpful in understanding the influence of attention and related cognitive processes on PPI.

Beyond the failure to replicate overall attentional modification of short-lead PPI, there was only modest evidence that nicotine influenced this process. PPI to attended tones was not significantly different from ignored tones at the 60-ms SOA but was modestly higher than ignored at the 240-ms SOA in the nicotine condition. However, this effect was weak statistically and did not involve the 120-ms SOA that is most typically sensitive to directed attention. Extending the above point regarding task difficulty, it may be that the effects of nicotine on early focused attention are more evident under very demanding task conditions.

More generally, there are few studies assessing nicotine's effect on focused attention, directly or indirectly via smoking, and they have produced mixed results. In deprived smokers, transdermal nicotine (Mancuso et al., 1999) and smoking (e.g., Domino & Kishimoto, 2002) increased focused attention, though similar studies found no effect using subcutaneous injection (Foulds et al., 1996) and nicotine gum (Knott et al., 2006). In non-smokers a subcutaneous injection of nicotine improved focused attention on an ERP task (Le Houezec et al., 1994). In a startle study, Rissling et al. (2007) found that attentional modification of short-lead PPI during a visual CPT was disrupted by smoking abstinence. In contrast, the present study employed auditory stimuli and administered nicotine to non-smokers. Although route of administration and type of assessment may be important moderators, the overall effect of nicotine on early focused attention does not appear be very strong.

Individual differences in attentional processing may be another key moderator (Bitsios et al., 2005; Newhouse et al. 2004). Consistent with the hypothesis that individuals with poorer attention may benefit more from nicotine, baseline (placebo) attentional processing significantly negatively correlated with the effect of nicotine: the lower the attentional modification of short-lead PPI during placebo, the greater the improvement with nicotine. Using Oldham's method (Oldham, 1962; Tu & Gilthorpe, 2007), it appeared that this effect is a true relationship, not simply regression toward the mean (RTM). That is, the correlations between the average of attentional modification for placebo and nicotine and the increase in attentional modification of PPI for nicotine compared to placebo remained reliable (Table 1, right), albeit substantially attenuated relative to the correlations between placebo alone and the difference score. Although statistical approaches to RTM are useful, alternative research designs which eliminate the concern altogether are preferable. Selecting participants or splitting the sample based on self-reported attention problems (e.g., Poltavski & Petros, 2006), performance on separate tests of attention such as a CPT, or separate baseline and placebo assessments (Swerdlow et al., 2003) all show promise. Still, the current work suggests that the attention-enhancing effect of nicotine on early auditory attention is at least partially dependent upon the fidelity of that processing in the absence of nicotine. Recent work on passive PPI reveals similar relations between baseline PPI and the effects of dopamine agonists (Bitsios, et al., 2005; Swerdlow et al., 2003).

Sustained Focused Attention

In the tone discrimination task, participants must sustain their attention for several seconds to judge the duration of ‘to be attended’ tones, providing a measure of sustained, focused attention. In the current study, startle magnitude was generally enhanced during attended tones compared to ignored tones, as previously observed (e.g., Dawson et al., 1993; Jennings et al., 1996). However, nicotine did not improve sustained focused attention in the present study. Given the large sample size and strong task performance, neither low power nor poor task performance can account for the lack of a nicotine effect. Though nicotine generally increases target detection rates and sustains these rates compared to placebo (e.g., Poltavski & Petros, 2006; Wesnes & Warburton, 1983), these studies utilized visual stimuli and may involve both vigilance and inhibitory processes that differ from those required in the current paradigm.

In addition to moderating task properties, individual differences may be important. As seen for short-lead PPI, initial correlations suggested a relationship between placebo attentional modification and change in attentional modification from placebo to nicotine conditions. However, Oldham's method indicated that this finding was likely due to RTM, suggesting that baseline differences do not play a role in nicotine's effect on focused, sustained attention.

Conclusion

Replicating and extending prior work, nicotine improved early, relatively automatic attentional filtering, as evidenced by an increase in overall PPI. The finding that the effect of nicotine on controlled early, focused attention appears to be related to baseline attentional processing is readily incorporated into theories regarding smoking behavior. Individuals with attention deficits may smoke in an attempt to self-medicate these deficits (e.g., Gilbert & Gilbert, 1995). Thus, it may be helpful to target attention in smoking prevention and cessation efforts, particularly in sub-groups of the population with attentional dysfunction. Conversely, nicotine may be useful as a treatment for cognitive disorders that are characterized by attentional dysfunction (Levin et al., 2001; Potter et al., 2006).

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Graduate Student Union Mark Diamond Research Award and the University at Buffalo Collage of Arts and Sciences Dissertation Fellowship Award granted to JSB. Completion of this manuscript was supported in part by grants MH069434 and CA111763 to LWH. This study was completed as part of the doctoral dissertation conducted by JSB under the supervision of LWH. The authors thank Jerry Richards, Craig Colder, and William Schmidt for their feedback on prior iterations of the dissertation manuscript. JSB is currently at the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS 39216, USA.

Footnotes

The effect of motivation and its interaction with nicotine on attention was also investigated in this study. Half of the participants were provided a monetary incentive for task performance on the attentional modification task; the remaining participants were simply asked to try their best. The between-subjects incentive manipulation did not have a significant effect on the dependent measures and is therefore excluded from this report due to space restrictions.

Participants with some lifetime exposure to nicotine were chosen because of the ethical issue of giving nicotine to nicotine-naïve individuals.

The reason for excluding over 20% of the sample is that the standard percentage metric can yield very extreme values, particularly when the MITI is quite small. The large number of within-subject conditions also increases the likelihood that at least one value will be aberrant. Indeed, participant attrition due to outlying startle values is common for this paradigm, with as many 50% of participants excluded even for single-session studies (e.g., Thorne et al., 2005).

As nicotine administered to non-smokers can cause negative effects, such as nausea, that may mask any positive effects on performance, nausea was considered as a covariate in supplementary analyses of startle modification. Nausea did not significantly account for variance in startle modification.

Because the pattern of baseline startle varied across patch order it is possible that the PPI and PPF results were mediated by differences in baseline responding. Correlations indicated that baseline startle during nicotine session and placebo session was highly correlated (.93), however baseline startle responding, in both patch conditions, was not correlated to attentional modification of PPI or PPF at any SOA, in either patch condition (correlations ranged between -.21 to .10).

References

- Acri JB, Grunberg NE, Morse DE. Effects of nicotine on the acoustic startle reflex amplitude in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1991;104:244–248. doi: 10.1007/BF02244186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashare RL, Hawk LW, Jr, Mazzullo RJ. Motivated attention: incentive effects on attentional modification of prepulse inhibition. Psychophysiology. 2007;44(6):839–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban MT, Losito BDG, Simons RF, Graham FK. Off-line latency and amplitude scoring of the human reflex eye blink with Fortran IV. Psychophysiology. 1986;23:612. [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL. Nicotine replacement therapy. What has been accomplished--can we do better? Drugs. 1993;45:157–170. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199345020-00001. erratum appears in Drugs 1993 May;45:736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitsios P, Giakoumaki SG, Frangou S. The effects of dopamine agonists on prepulse inhibition in healthy men depend on baseline PPI values. Psychopharmacology. 2005;182:144–152. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL, Geyer MA. Sensorimotor gating and schizophrenia. Human and animal model studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(2):181–188. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810140081011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control. Cigarette smoking among adults - United States, 2000. Morbid Mortal Weekly Report. 2002;51:642–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook EW, III, Atkinson LS, Lang KG. Stimulus control and data acquisition for IBM PCs and compatibles. Psychophysiology. 1987;24:726–727. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson ME, Hazlett EA, Filion DL, Nuechterlein KH, Schell AM. Attention and schizophrenia: impaired modulation of the startle reflex. J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102(4):633–641. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.4.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domino EF, Kishimoto T. Tobacco smoking increases gating of irrelevant and enhances attention to relevant tones. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(1):71–78. doi: 10.1080/14622200110098400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan E, Madonick S, Chakravorty S, Parwani A, Szilagyi S, Efferen T, et al. Effects of smoking on acoustic startle and prepulse inhibition in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156(23):266–272. doi: 10.1007/s002130100719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filion DL, Dawson ME, Schell AM. Modification of the acoustic startle-reflex eyeblink: a tool for investigating early and late attentional processes. Biological Psychology. 1993;35(3):185–200. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(93)90001-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filion DL, Dawson ME, Schell AM. The psychological significance of human startle eyeblink modification: A review. Biological Psychology. 1998;47:1–43. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(97)00020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulds J, Stapleton J, Swettenham J, Bell N, McSorley K, Russell MAH. Cognitive performance effects of subcutaneous nicotine in smokers and never-smokers. psychopharmacology. 1996;127:31–38. doi: 10.1007/BF02805972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DG, Gilbert BO. Personality, psychopathology, and nicotine response as mediators of the genetics of smoking. Behav Genet. 1995;25(2):133–147. doi: 10.1007/BF02196923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DG, Rabinovich NE, Rosenberger SR. Effects of fast and slow blood-rise nicotine patches on nausea and feeling states in never-smokers. Paper presented at the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco; New Orleans, LA. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Graham FK, Putnam LE, Leavitt LA. Lead-stimulation effects of human cardiac orienting and blink reflexes. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 1975;104:175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham FK. Constraints in measuring heart rate and period sequentially through real and cardiac time. Psychophysiology. 1978;15:492–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1978.tb01422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawk LW, Jr, Redford JS, Baschnagel JS. Influence of a monetary incentive upon attentional modification of short-lead prepulse inhibition and long-lead prepulse facilitation of acoustic startle. Psychophysiology. 2002;39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawk LW, Jr, Yartz AR, Pelham WE, Lock TM. The effects of methylphenidate on prepulse inhibition during attended and ignored prestimuli among boys with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychopharmacology. 2003;165:118–127. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1235-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heishman SJ, Taylor RC, Henningfield JE. Nicotine and smoking: A review of effects on human performance. Exp & Clin Psychopharm. 1994;2:345–395. [Google Scholar]

- Hindmarch I, Kerr JS, Sherwood N. Effects of nicotine gum on psychomotor performance in smokers and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1990;100(4):535–541. doi: 10.1007/BF02244008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HS, Ison JR. Reflex modification in the domain of startle: I. Some empirical findings and their implications for how the nervous system processes sensory input. Psychological Review. 1980;87(2):175–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings PD, Schell AM, Filion DL, Dawson ME. Tracking early and late stages of information processing: contributions of startle eyeblink reflex modification. Psychophysiology. 1996;33(2):148–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1996.tb02118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD. Smoking and attention: a review and reformulation of the stimulus- filter hypothesis. Clin Psychol Rev. 1997;17(5):451–478. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott VJ, Scherling CS, Blais CM, Camarda J, Fisher DJ, Millar A, et al. Acute nicotine fails to alter event-related potential or behavioral performance indices of auditory distraction in cigarette smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(2):263–273. doi: 10.1080/14622200600576669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V, Checkley SA, Gray JA. Effect of cigarette smoking on prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle reflex in healthy male smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;128(1):54–60. doi: 10.1007/s002130050109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V, Cotter PA, Checkley SA, Gray JA. Effect of acute subcutaneous nicotine on prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle reflex in healthy male non-smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;132(4):389–395. doi: 10.1007/s002130050360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Houezec J, Halliday R, Benowitz NL, Callaway E, Naylor H, Herzig K. A low dose of subcutaneous nicotine improves information processing in non-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1994;114(4):628–634. doi: 10.1007/BF02244994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Conners CK, Silva D, Canu W, March J. Effects of chronic nicotine and methylphenidate in adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9(1):83–90. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.9.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Conners CK, Silva D, Hinton SC, Meck WH, March J, et al. Transdermal nicotine effects on attention. Psychopharmacology. 1998;140:135–141. doi: 10.1007/s002130050750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, McClernon FJ, Rezvani AH. Nicotinic effects on cognitive function: behavioral characterization, pharmacological specification, and anatomic localization. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184(34):523–539. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso G, Warburton DM, Melen M, Sherwood N, Tirelli E. Selective effects of nicotine on attentional processes. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:199–204. doi: 10.1007/s002130051107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najem B, Houssiere A, Pathak A, Janssen C, Lemogoum D, Zhaet O, et al. Acute cardiovascular and sympathetic effects of nicotine replacement therapy. Hypertension. 2006;47:1162–1167. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000219284.47970.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse PA, Potter A, Singh A. Effects of nicotinic stimulation on cognitive performance. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2004;4:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham PD. A note on the analysis of repeated measurements of the same subjects. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1962;15:969–977. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(62)90116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poltavski DV, Petros T. Effects of transdermal nicotine on attention in adult non-smokers with and without attentional deficits. Physiol Behav. 2006;87(3):614–624. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postma P, Gray JA, Sharma T, Geyer M, Mehrotra R, Das M, et al. A behavioural and functional neuroimaging investigation into the effects of nicotine on sensorimotor gating in healthy subjects and persons with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184(34):589–599. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter AS, Newhouse PA, Bucci DJ. Central nicotinic cholinergic systems: a role in the cognitive dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Behav Brain Res. 2006;175(2):201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provost SC, Woodward R. Effects of nicotine gum on repeated adminsitration of the Stroop test. Psychopharmacology. 1991;104:536–540. doi: 10.1007/BF02245662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissling AJ, Dawson ME, Schell AM, Nuechterlein KH. Effects of perceptual processing demands on startle eyeblink modification. Psychophysiology. 2005;42(4):440–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissling AJ, Dawson ME, Schell AM, Nuechterlein KH. Effects of cigarette smoking on prepulse inhibition, its attentional modulation, and vigilance performance. Psychophysiology. 2007;44:627–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Stephany N, Wasserman L, Talledo J, Shoemaker J, Auerbach PP. Amphetamine effects on prepulse inhibition across-species: Replication and parametric extension. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:640–650. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y, Gilthorpe MS. Revisiting the relation between change and initial value: A review and evaluation. Statistics in Medicine. 2007;26:443–457. doi: 10.1002/sim.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesnes K, Warburton DM. Effects of smoking on rapid information processing performance. Neuropsychobiology. 1983;9(4):223–229. doi: 10.1159/000117969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]