Abstract

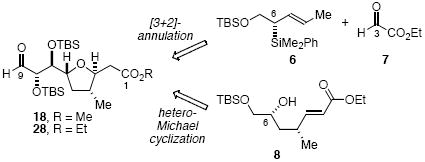

Stereoselective syntheses of the C(1)-C(9) fragments 18 and 28 of amphidinolide C have been developed. The first generation sequence involves a diastereoselective chelate-controlled [3 + 2]-annulation reaction of 6 and 7, while the second generation synthesis involves an intramolecular hetero-Michael cyclization of 8.

The amphidinolides are a structurally diverse group of natural products isolated from the symbiotic marine dinoflagellate Amphidinium sp. Kobayashi and coworkers have characterized more than 30 members of this family since 1986, many of which exhibit potent cytotoxicitity against human cancer cell lines.1 Not surprisingly, the amphidinolides have attracted considerable interest from the synthetic community. Total syntheses of many members of this class have been reported, with several resulting in stereochemical reassigments.2

Amphidinolide C3 (1) is one of the most cytotoxic members of this family, exhibiting in vitro cytotoxicities of 0.0058 and 0.0046 μg/mL against murine lymphoma L1210 and epidermoid carcinoma KB cells, respectively. Interestingly, the structurally related amphidinolides C24 (2) and F5 (3) display significantly reduced activities against these cell lines (0.8 and 3 μg/mL, respectively, for 2; 1.5 and 3.2 μg/mL, respectively for 3), suggesting that the C(25)-C(34) side chain plays an important role in the bioactivity of amphidinolides C, C2, and F. As such, amphidinolide C is an important target for synthesis and exploration as a lead compound for drug development. Several efforts on the synthesis of 1-3 have appeared, including a report from our laboratory on the synthesis of the C(11)-C(29) fragment of amphidinolide F.3b,6

A retrosynthetic analysis of 1-3 is presented in Figure 1. We envisage that these targets can be assembled from the major fragments 4 and 5 via a late-stage cross-coupling and macrolactonization sequence (or esterification followed by macrocyclization via intramolecular cross-coupling). Both fragments 4 and 5 possess trans-tetrahydrofuran ring systems that appeared to be excellent targets for synthesis via chelate-controlled [3+2]-annulation7 reactions of aldehydes and allylsilanes.8 We have previously reported the synthesis of an advanced precursor to 4 via a [3+2]-annulation sequence.6a At the outset, we envisaged that the C(1)-C(9) fragment 5 could be assembled efficiently via the chelate-controlled [3+2]-annulation reaction of crotylsilane 69 and an appropriate aldehyde coupling partner. In practice, a first-generation synthesis of 5a (X = H) was developed that proceeds via the [3+2]-annulation reaction of 6 and 7. Owing to the length of this first generation synthesis, we also developed a second generation sequence culminating in the synthesis of 5b (X = H) via the intramolecular hetero-Michael addition of 8. Both syntheses are presented herein.

Figure 1.

Amphidinolide C, retrosynthetic analysis

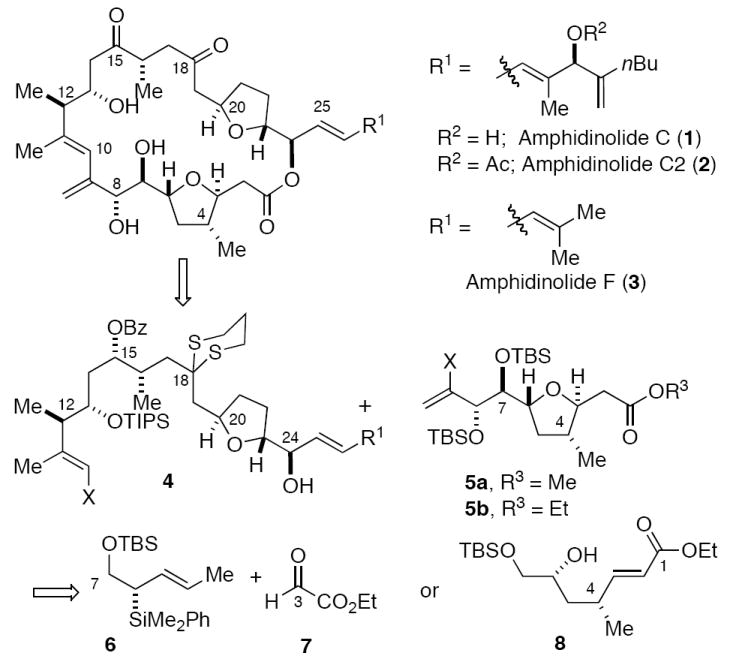

Allylsilane 6 was prepared in 75-91% ee by the known enantioselective Rh(II) catalyzed insertion of the diazoester derived from 9 into the Si-H bond of phenyldimethylsilane (Scheme 1).9 We initially targeted aldehydes 11 for use in chelate-controlled [3+2]-annulation reactions with 6, since this would introduce the correct number of carbon atoms in the C(3) substituent of tetrahydrofuran 12. The dithiane unit in 12a and the benzyl ether in 12b would also be sufficiently robust to survive the Hudrlik conditions10 that we initially contemplated using for protiodesilylation of 12 (a milder protocol for protiodesilylation was subsequently developed).11 However, all attempts to effect the chelate-controlled [3+2]-annulation reactions of 6 with either 11a or 11b and a variety of chelating Lewis acids (SnCl4, TiCl4, etc) failed to provide more than trace amounts of the 2,5-trans-tetrahydrofurans 12; rather, the 2,5-cis-tetrahydrofuran isomer (not shown) was obtained preferentially, indicating that the dithiane and benzyl ether units of 11a,b were incapable of forming a kinetically competent concentration of β-chelate with the aldehyde.12

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of tetrahydrofuran 13 via [3+2]-annulation reaction of 6 and 7

The required 2,5-trans-THF stereochemistry was successfully accessed via the SnCl4-promoted [3+2]-annulation reaction of crotylsilane 6 and ethyl glyoxalate (7) (Scheme 1). This reaction provided 13 in 82% yield with >20 : 1 diastereoselectivity. Further elaboration of 13 to the C(1)-C(9) fragment of amphidinolide C is summarized in Scheme 2.

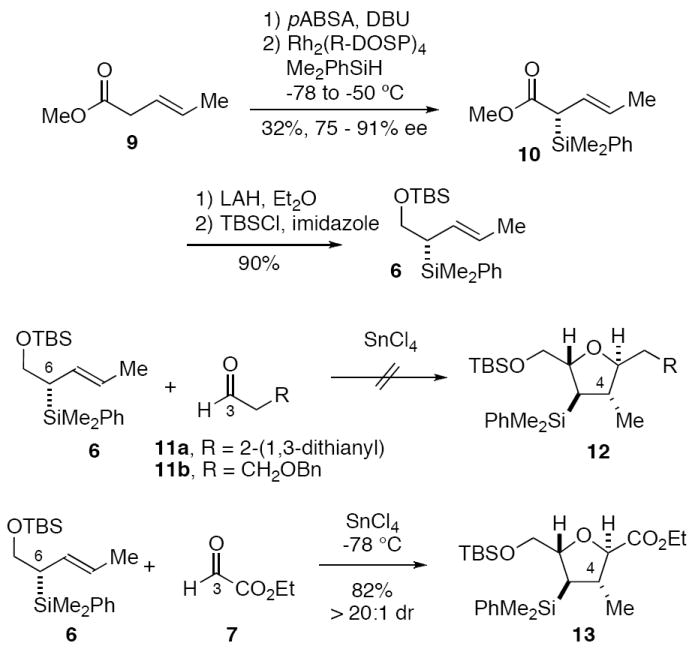

Scheme 2.

First generation synthesis of the C(1)-C(9) fragment 18 of amphidinolide C.

Reduction of 13 with DIBAL followed by conversion of the primary alcohol to the mesylate and then to the corresponding iodide set the stage for a one-carbon homologation via alkylation with 2-lithio-l,3-dithiane.13 This four-step sequence provided the 2,5-trans-THF 12a in 74% overall yield. Protiodesilylation of 12a using modified8a Hudrlik conditions (TBAF, KOtBu, DMSO, H2O, 18-crown-6)10 effected simultaneous deprotection of the primary TBS ether. Subsequent oxidation (SO3-pyridine, DMSO)14 of the primary alcohol gave aldehyde 14. Treatment of this intermediate with Brown’s γ-borylallylborane 1515 then gave anti-diol 16 in 47% yield with ca. 5:1 diastereoselectivity. Protection of the diol as a bis-TBS ether set the stage for dithiane deprotection (MeI, KHCO3, MeCN).16 Chlorite oxidation17 of the C(1)-carboxaldehyde and esterification of the resulting carboxylic acid provided ester 17 (same as 5a, X = H) in 34% yield for the four steps. Finally, ozonolysis of 17 provided the amphidinolide C C(1)-C(9) aldehyde 18 in 76% yield.

This synthesis of 18 proceeds in 13 steps from crotylsilane 6 in ca. 7% overall yield (17 steps from commercial precursors, including the synthesis of 6). This synthesis of 18 was too lengthy for an intermediate of such modest complexity, with seven steps devoted to elaboration of the methoxycarbonyl group of tetrahydrofuran 13. Thus, our inability to effect the chelate-controlled [3+2]-annulation reaction of 6 and 11a or 11b proved to be quite costly. We therefore decided to pursue a second generation approach, in which the trans-THF unit is assembled via the intramolecular hetero-Michael cyclization of 8 (see Scheme 3).

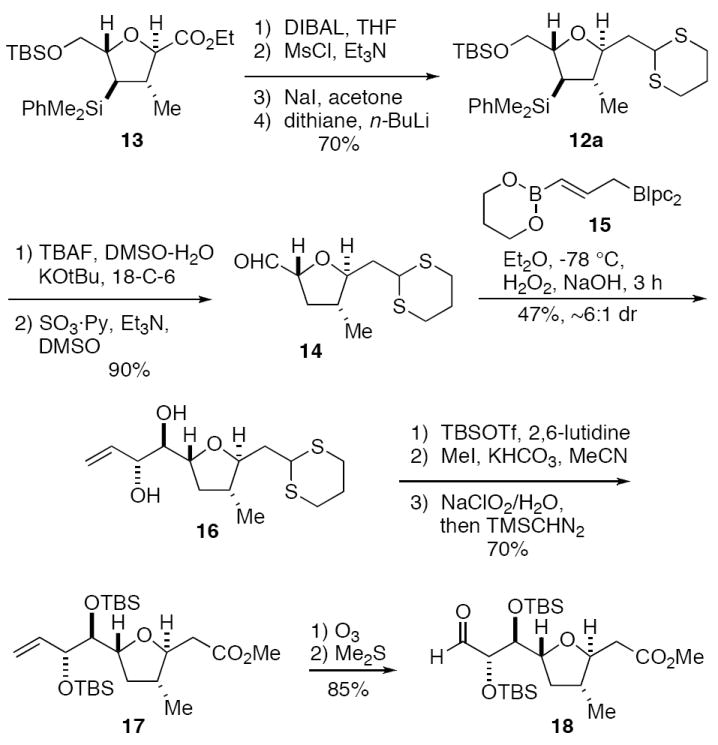

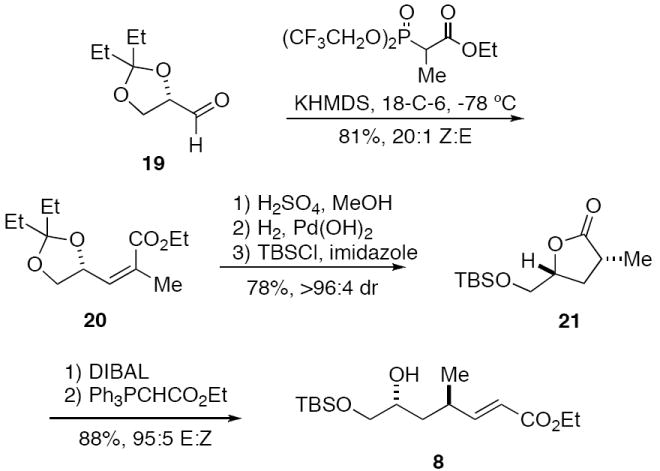

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of cyclization substrate 8

The second generation sequence began with the Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons olefination of glyceraldehyde isopentylidene ketal 1918 using the Still-Genari reagent. 19 This provided Z-enoate 20 with >96:4 Z:E selectivity. Acid catalyzed deprotection of the pentylidene ketal and spontaneous in situ lactonization of the γ-hydroxy ester, followed by diastereoselective hydrogenation of the butenolide double bond20 and protection of the primary alcohol gave lactone 21 with 20:1 diastereoselectivity. DIBAL reduction of 21 gave the corresponding lactol, which was converted to 8 by treatment with the stabilized ylide Ph3P=CHCO2Me.

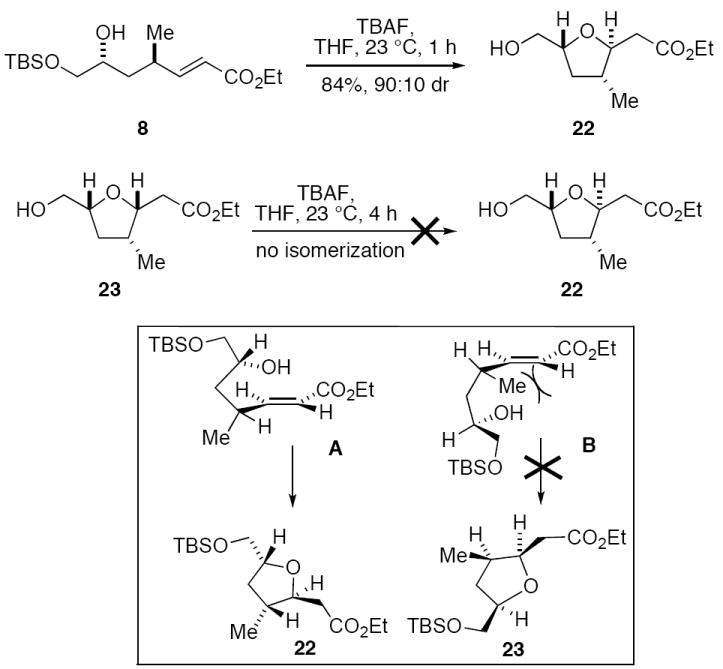

Treatment of 8 with TBAF in THF effected the intramolecular Michael cyclization with simultaneous deprotection of the TBS ether, and provided tetrahydrofuran 22 with 9:1 diastereoselectivity in 84% yield (Scheme 4). An analogous cyclization was reported by Kobayashi and coworkers during their stereochemical assignment work on amphidinolide C.3c This transformation evidently proceeds under kinetic control, as treatment of the minor tetrahydrofuran diastereomer 23 with TBAF in THF at ambient temperature did not provide any 22. The diastereoselectivity of the kinetically controlled cyclization of 8 can be rationalized by minimization of A1,3-strain in transition state A.21

Scheme 4.

TBAF-promoted cyclization of 8

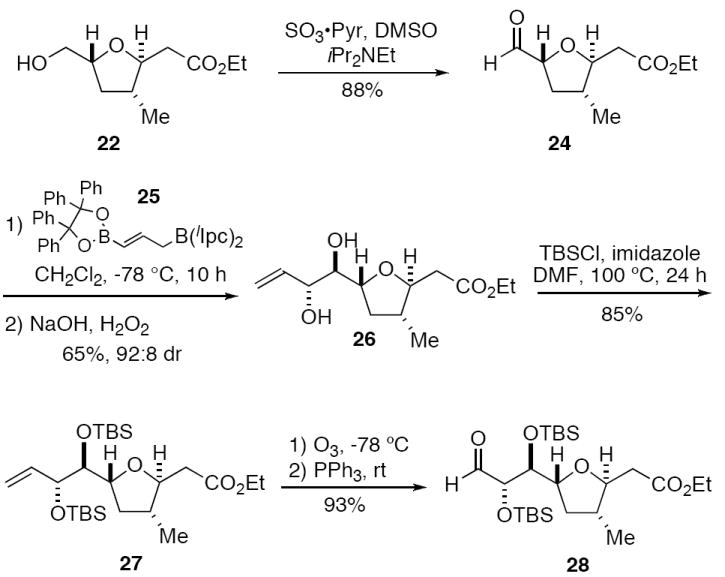

Tetrahydrofuran 22 was elaborated to the amphidinolide C C(1)-C(9) fragment 28 as summarized in Scheme 5. Oxidation of 22 with DMSO-pyridine under Parikh-Doering conditions13 gave aldehyde 24. Allylboration of 24 with the second genaration γ-borylallylborane 25 developed in our laboratory22 provided diol 26 with 92 : 8 diastereoselectivity. Diol 26 was then protected as the bis-TBS ether 27 (same as 5b, X = H). Ozonolysis of 27 then gave aldehyde 28, which differs from aldehyde 18 (Scheme 2) only with respect to the ethyl versus a methyl ester. This second generation synthesis of 28 was completed in 11 steps from aldehyde 19 (13 from commercial materials) in 21% overall yield.

Scheme 5.

Completion of the second generation synthesis of the C(1)-C(9) fragment 26 of amphidinolide C.

In summary, we have developed two syntheses of the C(1)-C(9) fragment of amphidinolide C. The first generation synthesis involving the chelation-controlled [3 + 2]-annulation reaction of 6 and glyoxylate 7 provided 2,5-trans-tetrahydrofuran 13 that was elaborated to the C(1)-C(9) fragment 18 by an 11-step sequence (Scheme 2). However, this effort was compromised by the inability to effect chelate-controlled [3+2]-annulations with aldehydes 11a or 11b, which would have led to a much shorter synthesis of 18 if successfully implemented. Consequently, a more efficient second-generation synthesis of the C(1)-C(9) fragment 28 was developed that proceeds via the kinetically controlled Michael cyclization of 8 (Scheme 5). The latter sequence is the one that we now use for bringing up material in onging efforts to complete total syntheses of amphidinolides C, C2, and F. Studies along these lines will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures and full spectroscopic data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.For recent reviews, see: Kobayashi J, Ishibashi M. Chem Rev. 1993;93:1753.Chakraborty T, Das S. Curr Med Chem : Anti-Cancer Agents. 2001;1:131. doi: 10.2174/1568011013354660.Kobayashi J, Shimbo K, Kubota T, Tsuda M. Pure Appl Chem. 2003;75:337.Kobayashi J, Tsuda M. Nat Prod Rep. 2004;21:77. doi: 10.1039/b310427n.

- 2.An up to date list of references for total syntheses of members of the amphidinolide family is provided in the Supporting Information.

- 3.(a) Kobayashi J, Ishibashi M, Wälchli M, Nakamura H, Hirata Y, Sasaki T, Ohizumi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:490. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ishiyama H, Ishibashi M, Kobayashi J. Chem Pharm Bull. 1996;44:1819. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kubota T, Tsuda M, Kobayashi J. Org Lett. 2001;3:1363. doi: 10.1021/ol015741z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kubota T, Tsuda M, Kobayashi J. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:1613. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kubota T, Sakuma Y, Tsuda M, Kobayashi J. Marine Drugs. 2004;2:83. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi J, Tsuda M, Ishibashi M, Shigemori H, Yamasu T, Hirota H, Sasaki T. J Antibiot. 1991;44:1259. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Shotwell JB, Roush WR. Org Lett. 2004;6:3865. doi: 10.1021/ol048381z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mohapatra DK, Rahaman H, Chorghabe MS, Gurjar MK. Synlett. 2007:567. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Panek J, Yang M. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:9868. [Google Scholar]; (b) Panek J, Beresis R. J Org Chem. 1993;58:809. [Google Scholar]; (c) Micalizio G, Roush W. Org Lett. 2000;2:461. doi: 10.1021/ol9913082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Micalizio GC, Roush WR. Org Lett. 2001;3:1949. doi: 10.1021/ol0160250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tinsley JM, Roush WR. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10818. doi: 10.1021/ja051986l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tinsley JM, Mertz E, Chong PY, Rarig R-AF, Roush WR. Org Lett. 2005;7:4245. doi: 10.1021/ol051719k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Mertz E, Tinsley JM, Roush WR. J Org Chem. 2005;70:8035. doi: 10.1021/jo0511290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Va P, Roush WR. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15960. doi: 10.1021/ja066663j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Va P, Roush WR. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:5768. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Huh CW, Roush WR. Org Lett. 2008;10:3371. doi: 10.1021/ol801242d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Davies H, Hansen T, Rutberg J, Bruzinski P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:1741. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bulugahapitiya P, Landais Y, Parra-Rapado L, Planchenault D, Weber V. J Org Chem. 1997;62:1630. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Hudrlik P, Hudrlik A, Kulkarni A. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:6809. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hudrlik P, Holmes P, Hudrlik A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:6395. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hudrlik P, Gebreselassie P, Tafesse L, Hudrlik A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:3409. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heitzman CL, Lambert WT, Mertz E, Shotwell JB, Tinsley JM, Va P, Roush WR. Org Lett. 2005;7:2405. doi: 10.1021/ol0506821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Mengel A, Reiser O. Chem Rev. 1999;99:1191. doi: 10.1021/cr980379w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Reetz MT. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1984;23:556. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seebach D, Wilka EM. Synthesis. 1976:476. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parikh J, Doering W. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:5505. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown HC, Narla G. J Org Chem. 1995;60:4686. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takano S, Hatakeyama S, Ogasawara K. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1977:68. doi: 10.1021/ja00426a062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kende AS, Johnson S, Sanfilippo P, Hodges JC, Jungheim LN. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:3513. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid CR, Bradley DA. Synthesis. 1992:587. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Still WC, Gennari C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:4405. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herdeis C, Lütsch K. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1993;4:121. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmann RW. Chem Rev. 1989;89:1841. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flamme EM, Roush WR. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3644. doi: 10.1021/ja028055j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures and full spectroscopic data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.