Abstract

Background

Nitrogen (N2) fixation also yields hydrogen (H2) at 1∶1 stoichiometric amounts. In aerobic diazotrophic (able to grow on N2 as sole N-source) bacteria, orthodox respiratory hupSL-encoded hydrogenase activity, associated with the cell membrane but facing the periplasm (exo-hydrogenase), has nevertheless been presumed responsible for recycling such endogenous hydrogen.

Methods and Findings

As shown here, for Azorhizobium caulinodans diazotrophic cultures open to the atmosphere, exo-hydrogenase activity is of no consequence to hydrogen recycling. In a bioinformatic analysis, a novel seven-gene A. caulinodans hyq cluster encoding an integral-membrane, group-4, Ni,Fe-hydrogenase with homology to respiratory complex I (NADH : quinone dehydrogenase) was identified. By analogy, Hyq hydrogenase is also integral to the cell membrane, but its active site faces the cytoplasm (endo-hydrogenase). An A. caulinodans in-frame hyq operon deletion mutant, constructed by “crossover PCR”, showed markedly decreased growth rates in diazotrophic cultures; normal growth was restored with added ammonium—as expected of an H2-recycling mutant phenotype. Using A. caulinodans hyq merodiploid strains expressing β-glucuronidase as promoter-reporter, the hyq operon proved strongly and specifically induced in diazotrophic culture; as well, hyq operon induction required the NIFA transcriptional activator. Therefore, the hyq operon is constituent of the nif regulon.

Conclusions

Representative of aerobic N2-fixing and H2-recycling α-proteobacteria, A. caulinodans possesses two respiratory Ni,Fe-hydrogenases: HupSL exo-hydrogenase activity drives exogenous H2 respiration, and Hyq endo-hydrogenase activity recycles endogenous H2, specifically that produced by N2 fixation. To benefit human civilization, H2 has generated considerable interest as potential renewable energy source as its makings are ubiquitous and its combustion yields no greenhouse gases. As such, the reversible, group-4 Ni,Fe-hydrogenases, such as the A. caulinodans Hyq endo-hydrogenase, offer promise as biocatalytic agents for H2 production and/or consumption.

Introduction

Azorhizobium caulinodans is an obligate oxidative, microaerophilic bacterium originally isolated from stem- and root-nodules of the legume host plant Sesbania rostrata [1]. In legume nodules, endosymbiotic rhizobia, including A. caulinodans, fix atmospheric dinitrogen (N2) yielding ammonium as utilizable N-source for the host plant. Unlike typical rhizobia which fix N2 only endosymbiotically, A. caulinodans is also diazotrophic (able to grow on N2 as N-source in pure culture). Both processes are owed to molybdenum-containing (Mo) dinitrogenase, an α2β2-tetrameric protein complex catalyzing directed electron-transfer. Metabolic electrons are tapped from pyruvate oxidation [2] and singly transmitted via flavo- and FeS-proteins ultimately to the Mo-dinitrogenase catalytic center, its iron-molybdenum cofactor (FeMo-co); the enzyme complex effectively operates an 8-electron reductive cycle of recursive single electron transfers [3], [4]. At the FeMo-co center, the first two arriving electrons combine with hydrogen-ions to yield a molecule of H2. The bound H2 is then displaced by N2, and the subsequent six, arriving electrons, together with hydrogen-ions, now reduce N2 to yield two molecules of ammonium as co-product:

In vivo, H2 yields (relative to 1∶1 in vitro stoichiometry) may further increase as a function of Mo-dinitrogenase turnover [5]. As the substrate N2 triple-bond is highly unreactive, the dinitrogenase catalytic cycle is kinetically limiting as an in vivo biochemical standard process. To accelerate catalysis and render such thermodynamically favorable, Mo-dinitrogenase is both one-electron reduced and energetically charged by homodimeric dinitrogenase reductase, which harbors a bridging 4Fe-4S-center and two ATP binding sites, one per subunit. During single-electron transfer from dinitrogenase reductase to Mo-dinitrogenase, 2 ATP hydrolyze to yield 2 ADP and 2 orthophosphate (Pi). Thus, in the 8-electron dinitrogenase complex catalytic cycle:

earning Mo-dinitrogenase complex activity distinction as the most ATP-consumptive metabolic reaction on a per substrate basis [5].

Notably, A. caulinodans diazotrophic cultures, as with other aerobic diazotrophic bacteria, do not evolve significant H2. Rather, H2 produced by Mo-dinitrogenase complex activity is efficiently recycled as respiratory electron donor to O2 (as preferred electron-acceptor), thus recouping by oxidative phosphorylation ATP invested in H2 production as part of the dinitrogenase catalytic cycle:

which represents some 25% of total ATP invested in N2 fixation [6].

H2 production has long been associated with N2 fixation in pure diazotrophic cultures of both fermentative and oxidative bacteria as well as by endosymbiotic rhizobia in legume nodules [7]. Endogenous H2 recycling, both in diazotrophic bacterial cultures [8] as well as in certain symbiotic nodules, among those, garden pea [9], has been presumed owed to a respiratory Ni,Fe-hydrogenase activity highly conserved among disparate aerobic diazotrophic bacteria [10], [11]. As studied in archetypal aerobic bacteria such as Ralstonia eutropha, orthodox respiratory hydrogenase is a heterodimeric protein comprising a bimetallic Ni,Fe-catalytic subunit and a 4Fe-4S-center subunit, which complex with an integral-membrane b-type cytochrome, linking Ni,Fe-hydrogenase H2-oxidizing activity to cellular respiration and oxidative phosphorylation [12].

To the contrary, as we report here for A. caulinodans diazotrophic cultures open to the environment, endogenous H2 is not recycled via orthodox respiratory exo-hydrogenase activity but instead via a novel respiratory endo-hydrogenase complex, presumably reflecting the need to sequester endogenous H2 by metabolic channeling.

Results

A. caulinodans exo-hydrogenase deletion mutants lose chemoautotrophy but retain diazotrophy

To study the metabolic role of the orthodox respiratory exo-hydrogenase activity for H2 recycling in diazotrophic culture, A. caulinodans haploid strain 66081 carrying an in-frame hupΔSL2 allele (Table 1), a result of perfect gene-replacement, was constructed by “crossover PCR” mutagenesis [13] (Fig. 1; Methods). To verify its hupSL deletion genotype, strain 66081 genomic DNA served as template for diagnostic PCR analysis. Using haploid genomic oligodeoxynucleotides HupSL-Prox and HupSL-Dist (Table 1; Fig. 1) as primer-pair, a single, novel 2.3 kbp DNA fragment was amplified from the 66081 genome, as template, and then sequenced on both strands. Strain 66081 therefore carries the in-frame hupΔSL2 allele, arisen by perfect gene-replacement. When tested in chemoautotrophic liquid batch cultures (under 20% H2 as sole energy source, 5% CO2 as sole C-source, 2% O2, bal. N2) with ammonium added as sole N-source, whereas parental strain 61305R (virtual wild-type; Methods) grew, strain 66081(hupΔSL2) did not. Therefore, HupSL exo-hydrogenase activity is required for respiration with exogenous hydrogen. When tested in diazotrophic liquid batch cultures (Methods), strains 61305R and 66081(hupΔSL2) both proved fully proficient (able to grow on N2 as sole N-source; Nif+ phenotype), in comparison to Nif− strains 60107R(nifA) and 60035R(nifD), both deficient [14]. Strain 66081(hupΔSL2) also grew as wild-type when plated on solid, defined medium lacking added-N, thus requiring use of atmospheric N2 (Methods). Therefore, orthodox respiratory HupSL exo-hydrogenase activity was not material to growth, nor, by presumption, endogenous H2 recycling in A. caulinodans diazotrophic cultures.

Table 1. Bacterial strains and oligodeoxynucleotide primers employed.

| Azorhizobium caulinodans | ||

| 57100 | ORS571 wild-type | [1] |

| 60035R | 57100 nifD35R | [14] |

| 60107R | 57100 nifA107R | |

| 61305R | 57100 Nic− 6-OH-Nic+ | [29] |

| 66081 | 61305R hupΔSL2 | |

| 66132 | 61305R hyqΔRI7 | |

| 66203 | 61305R hupΔSL2 hyqΔRI7 | |

| 66205 | 57100 hyqR::uidA+ hyqΔBI, hyq+ merodiploid | |

| 66210 | 60107R nifA107R hyqR::uidA+ hyqΔBI, hyq+ merodiploid | |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| MH3000 | Δ(ara-leu)7697 Δlac(IPOZY)X74 galU araD139 galK rpsL ompR101 | [32] |

| SM10 | MM294[::pRP4ΔTn1 Tcs] recA Tra(IncP1)+ Kmr | [33] |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSUP202 | pBR325 mob Apr Tcr Cmr | [33] |

| pHupΔSL2 | pSUP202 hupΔSL2 | |

| pHyq ΔRI7 | pSUP202 hyqΔRI7 | |

| pHyqRU5 | pHyqΔRI7 hyqR::uidA+ | |

| Oligodeoxynucleotide primers | ||

| HupSL-Prox | GCCGCAAGGCGCTGCTGA | |

| HupSL-A | GAAGACGAATTCGCCCGCG | |

| HupSL-B | GCCGTCGACGAGCGAGAGGCAAAGGTCTCGAGGCCGGCCAT | |

| HupSL-C | TGCCTCTCGCTCGTCGACGGCACCGTGCGCTGAGGGGAGGG | |

| HupSL-D | CTCGAATTCAAGAGCCATGCC | |

| HupSL-Dist | ACCTCCGACGGTGCGGTCT | |

| Hyq-Prox | GAACAGGCGGTGCCAGTTG | |

| Hyq-A | GCGGAATTCAGGCTGAGGC | |

| Hyq-B | GCCGTCGACGAGCGAGAGGCAGGTGATCATGTGGCCGAAAGA | |

| Hyq-C | TGCCTCTCGCTCGTCGACGGCCAAAGGGATTAGCCAACACGT | |

| Hyq-D | CTTCGAATTCGGGCCGC | |

| Hyq-Dist | CGGACCATCGCTCTGGC | |

| 21-Up | GCCGTCGACGAGCGAGAGGCA | |

| 21-Down | TGCCTCTCGCTCGTCGACGGC | |

| UidA-Prox | CTCGTCGAC TTACGTCCTGTAGAAACCCCAAC | |

| UidA-Dist | GCCGTCGAC TTGTTTGCCTCCCTGCTGCGG | |

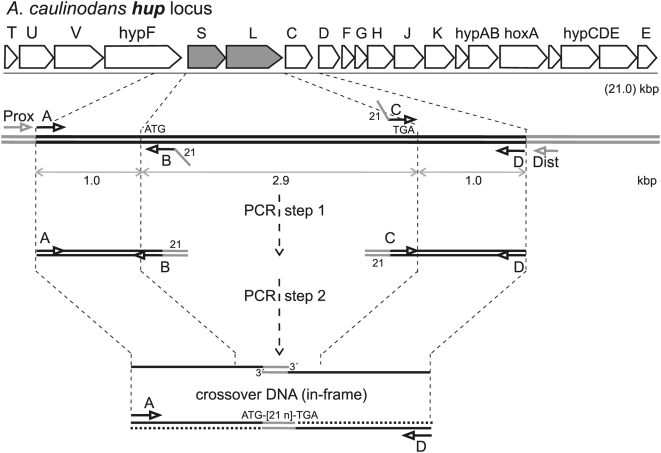

Figure 1. A. caulinodans hup genetic locus and physical map: creation of in-frame translational fusion deletions.

The top line represents the genetic map of the 20-gene hup polycistronic operon spanning 21 kbp. The second line represents an expanded physical map of hupSL DNA indicating postions of and (5′→3′) polarity for synthetic A, B, C, and D oligodeoxynucleotide primers of genome-identical sequence used in two, separate PCR reactions to generate DNA fragments A→B and C→D. The third line indicates a follow-up PCR reaction in which DNA fragments A→B and C→D were mixed, thermally denatured, allowed to partially renature, and used as combination PCR template/primer. As synthetic primers B and C share a complementary 21 bp extension sequence (angled line), the A→B Watson and C→D Crick strands (and vice versa) may partially reanneal via this 21 bp linker sequence In the third line, when such occurs, the resulting, partially-reannealed A→B(21 bp)C→D spliced DNA fragment which carries 5′-overhangs and free 3′-ends on both strands is a template for the thermostable DNA polymerase elongation reaction, producing a finished A→D duplex DNA fragment which may then be further amplified by PCR in the presence of added A and D primers. As verified by DNA sequencing analysis, finished, amplified A→D duplex fragments carry a genetic crossover which fuses (via the 21 bp linker sequence) in-frame the “start” codon of the proximal hupS gene to the “stop” codon of the distal hupL gene. Primers A and D may be extended with genome non-complementary elements to facilitate molecular cloning of resulting A→D fragments (Table 1). In vivo using homologous genetic recombination, wild-type loci are then exchanged for recombinant A→D crossover DNA fragments, which yield in-frame, translational deletion alleles of target genes of interest (Methods).

Bioinformatic identification of a novel respiratory endo-hydrogenase gene-cluster

A. caulinodans ORS571 genome fragments were then assembled and screened for additional hydrogenase genes. Previously identified, and localized to the same polycistronic operon carrying the hupSL genes, were the hupUV genes encoding a cytoplasmic sensory hydrogenase activity [15]. From both nucleotide and protein multiple sequence alignments, the A. caulinodans hupUV genes proved orthologs of the R. eutropha hoxBC genes, which encode a sensory Ni,Fe-hydrogenase coupled to the HoxJ histidine kinase; in R. eutropha, this soluble HoxBCJ complex senses H2 availability, transactivates hox [hup] genes in response to H2 and is necessarily present only at very low catalytic activity on a per cell basis [16]. Thus, we broadened the hydrogenase search to unlinked loci, initially without benefit of an A. caulinodans genomic sequence. Using the BLAT algorithm [17] to search an (∼8 Mbp total) A. caulinodans ORS571 shotgun genome sequence dataset (generously provided by B. A. Roe, unpublished results), we assembled several contigs spanning an ∼8 kbp genomic sequence, unlinked to the hup operon, but showing homology to Ni,Fe-hydrogenase genes (Fig. 1). From these genome-contigs, we designed synthetic oligodeoxynucleotide primers, carried out PCR amplification and nucleotide sequencing, and assembled the complete sequence for a novel, tightly organized, seven-gene hyqRBCEFGI operon (GenBank accession: FJ378904; Fig. 2). In the presumed hyq operon, the distal hyqGI genes encode a canonical heterodimeric Ni,Fe-hydrogenase. The hyqBCEF genes all specify integral-membrane proteins orthologous to the Escherichia coli hyf genes, whose syntax in labeling the A. caulinodans hyq genes, including hyqGI, has thus been conserved. (Note the A. caulinodans hyq operon however lacks both E. coli hyfA and hyfD genes.) The E. coli hyf operon encodes hydrogenase-4 [18], an integral-membrane complex representative of the H2-evolving or group-4 hydrogenases, previously identified in and restricted to anaerobic bacteria [11].

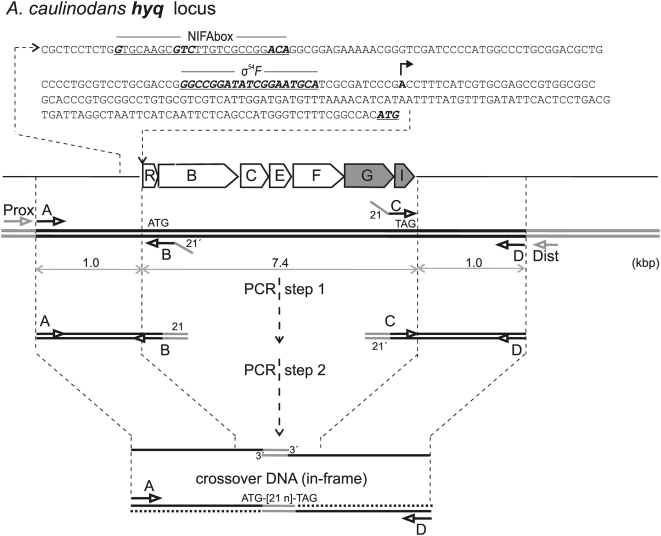

Figure 2. A. caulinodans hyq genetic locus and physical map: creation of in-frame, translational fusion deletions.

The main line represents the genetic map of the 7-gene hyq polycistronic operon (7.4 kbp coding DNA). Superimposed above is the ∼300 np sequence upstream of the hyqR start (ATG) codon, presumably comprising the hyq control region, which includes a canonical NIFAbox element, facilitating binding of the NIFA transcriptional activator, adjacent to a σ54F-box element, allowing initiation by RNA polymerase·σ54F complex (see Results). For additional details, please refer to Fig 1.

As well, the group-4 integral-membrane hydrogenases include multiple subunits homologous to those of respiratory NADH : quinone dehydrogenase (NADH-DH), an integral membrane complex whose active site for NADH oxidation faces the cytoplasm [11], [18], [19]. Such homology extends to both NADH-DH L0 (integral-membrane) and L1 (membrane-associated) sub-complex proteins. By analogy to NADH-DH, and to conceptually distinguish the two A. caulinodans cell membrane-associated, respiratory hydrogenases, we therefore denote the presumed HyqBCEFGI complex as endo-hydrogenase and the HupSL+cytb complex as exo-hydrogenase, so as to distinguish relative orientations of substrate oxidative sites: the former presumably facing the cell interior (cytoplasm), the latter facing the cell exterior (periplasm). As the A. caulinodans genome encodes bona fide respiratory complex I in an unlinked 15-gene operon (AZC_1667 to AZC_1681) [20], the hyq genes and their encoded endo-hydrogenase complex, while similar, are indeed structurally and functionally distinct.

A. caulinodans Hyq endo-hydrogenase activity facilitates growth in diazotrophic cultures open to the environment

To test metabolic role(s) for the presumptive Hyq endo-hydrogenase complex, an A. caulinodans hyq operon deletion (hyqΔRI7) allele was constructed using crossover PCR, in which the hyqR start- and hyqI stop-codons were fused in-frame by a 21 bp linker sequence (Fig. 2; Methods). In both strain 61305R(virtual wild-type) and 66081(hupΔSL2), the wild-type hyq + operon was then swapped for this hyqΔRI7 allele by homologous recombination (Methods). As with strain 66081, the resulting haploid strain 66132 was verified by combined PCR and DNA sequencing analyses. Using haploid genomic Hyq-Prox and Hyq-Dist oligodeoxynucleotides (Table 1; Fig. 2) as primer-pair and strain 66132 genomic DNA as template, a single 2.2 kbp DNA fragment was amplified by PCR and then sequenced on both strands using either Hyq-Prox or Hyq-Dist as DNA sequencing primers. Accordingly, strain 66132 proved a true hyqΔRI7 haploid arisen by perfect gene-replacement. Similarly, starting with strain 66081(hupΔSL2), strain 66203 proved a true double-mutant haploid, carrying both hupΔSL2 and hyqΔRI7 alleles.

Growth kinetics of four haploid strains, 61305R and its descendants 66081(hupΔSL2), 66132(hyqΔRI7) and 66203(hupΔSL2, hyqΔRI7) were analyzed in liquid batch cultures with defined media. For all strains, batch cultures were started in defined medium with 40 mM succinate added as sole C- and energy-source, and 0.5 mM ammonium added as N-source. All starter cultures grew exponentially up to viable cell counts of ∼1×108 ml−1 at which growth arrested due to ammonium limitation (as when 5 mM ammonium was then added, exponential growth rapidly resumed for at least two additional cell doublings). These N-limited, static cultures were one-thousandfold diluted into the same defined growth medium with or without added 5 mM ammonium, placed in sealed 30 ml vials, sealed and subcultured with continuous sparging (6 ml min−1) using a defined gas mixture (2% O2, 5% CO2, bal. N2). Samples were periodically withdrawn and plated on rich medium for viable cell counts (Methods). Whether in the presence and absence of added ammonium, strains 61305R and 66081(hupΔSL2) grew similarly (Table 2). In contrast, while both strains 66132(hyqΔRI7) and 66203(hupΔSL2, hyqΔRI7) grew similarly in the presence of added ammonium, cell doubling-times slowed 21% in the absence of ammonium, relative to strains 61305R and 66081 (Table 2).

Table 2. Exponential growth rates of A caulinodans strains in diazotrophic liquid batch cultures at 29°C.

| Strain | 2% O2, 5% CO2, bal. N2 atmosphere (hr) | |||||

| N-source | ||||||

| +5 mM NH4 + | atm N2 only | |||||

| − | − | atm+20% H2 | ||||

| t D | t D(w)/t D | t D | t D(w)/t D | t D | t D(w)/t D | |

| 61305R | 2.3* | (1.0)† | 7.2* | (1.0)† | 4.2* | (1.0)† |

| 66081 hupΔSL | 2.3 | (1.0±.04) | 7.2 | (1.0±.03) | 6.8 | (0.62±.02) |

| 66132 hyqΔRI | 2.4 | (0.96±.03) | 8.8 | (0.82±.02) | 5.0 | (0.84±.03) |

| 66203 hupΔSL hyqΔRI | 2.4 | (0.95±.05) | 8.8 | (0.80±.04) | 8.8 | (0.48±.02) |

doubling-time; representative single experiment.

doubling-time relative to wild-type (w); multiple experiments.

These growth experiments were repeated, except that cultures were sparged with an H2-enriched defined gas mixture (2% O2, 5% CO2, 20% H2, bal. N2). With the inclusion of H2 at saturating metabolic levels in the sparge gas, strains 61305R and 66132(hyqΔRI7) when cultured without added ammonium both grew much faster. In one experiment, the diazotrophic cell doubling-time for strain 61305R was cut from 7.2 to 4.16 hr, that for 66132 was cut from 8.8 to 5.0 hr, both in the presence of 20% H2 (Table 2). Therefore, while A. caulinodans growth rates in liquid diazotrophic cultures were otherwise limited by N2 fixation (Table 2), acceleration of oxidative phosphorylation with added 20% H2 as respiratory electron-donor also accelerated growth, as is generally characteristic of microaerophilic bacteria [21]. Nevertheless, even with exogenous H2 added in sparge gases at levels sufficient to yield maximum growth-rate enhancement, the 21% growth deficit observed for 66132(hyqΔRI7) versus parental 61305R persisted. Therefore, cell bioenergetic role(s) for Hyq endo-hydrogenase and HupSL exo-hydrogenase activities are not entirely synonymous. By analogy to NADH-DH complex activities, Hyq endo-hydrogenase activity might also be membrane proton-motive and/or electrogenic, translocating multiple ions such a H+, K+ and/or Na+ (see Discussion).

In contrast, strain 66081(hupΔSL2) showed only a slight increase in growth rate in diazotrophic culture, and strain 66203(hupΔSL2, hyqΔRI7) showed no detectable increase in growth rate, both in response to added 20% H2 (Table 2). Therefore in A. caulinodans, exogenous H2-driven respiration is essentially run by HupSL exo-hydrogenase activity, marginally augmented by Hyq endo-hydrogenase activity. In contrast, for diazotrophic cultures open to the atmosphere, endogenous H2 (produced by Mo-dinitrogenase activity) was exclusively recycled by Hyq endo-hydrogenase activity. In enclosed cultures, or when liquid batch diazotrophic cultures open to the atmosphere became sufficiently dense near saturation (>1×108 cells ml−1) some amount of endogenous H2 recycling by HupSL exo-hydrogenase activity was detected (data not presented).

The A. caulinodans hyq operon is strongly and specifically induced in diazotrophic cultures

To assess growth conditions in which the hyq operon was genetically expressed, A. caulinodans strains using β-glucuronidase activity to report hyq operon transcription were constructed. The E. coli uidA+ gene, encoding β-glucuronidase, was amplified by PCR and, using standard in vitro molecular cloning techniques, the resulting 1.8 kbp uidA + coding sequence was inserted in-frame into the 21 bp crossover linker sequence of pHyqΔRI7 yielding plasmid pHyqRU5 (Table 1; Methods). Derived from both A. caulinodans 57100 and 60107R(nifA) as parent, hyq merodiploid strains 66205 and 66210, both carrying an upstream in-frame fusion hyqR::uidA + hyqΔBI operon in tandem with the downstream hyq + operon, were isolated and verified by both PCR and DNA sequencing analyses (Methods). Merodiploid hyq reporter strain 66205 was first tested for bacterial colony appearance on solid defined media supplemented with X-Gluc (Methods) as chromogenic β-glucuronidase substrate. When inoculated onto defined medium also supplemented with 5 mM ammonium and cultured in fully aerobic conditions, strain 66205 colonies were white, lacking any evidence of β-glucuronidase activity. When the same petri plates were incubated under a reduced O2 atmosphere (2% O2, 5% CO2, bal. N2), strain 66205 colonies appeared light-blue, or partially induced. When 0.5 mM L-glutamine was added to solid culture medium, 66205 colonies were again completely white when incubated under 2% O2 indicating the hyq operon was strongly repressed. When 66205 was cultured diazotrophically (in the absence of added ammonium and L-glutamine) under reduced O2, colonies were dark blue, indicative of strong hyq operon expression.

To obtain quantitative data for both strains 66205 and 66210, liquid batch cultures were pre-grown aerobically in defined medium with 0.5 mM ammonium as N-source to cell titers of ∼1×108 ml−1 (at which available ammonium was exhausted) and physiologically shifted to diazotrophic culture conditions (Methods) for 12 hr at 29°C. Cells were then harvested and β-glucuronidase specific activities were measured in cell-free extracts (Methods). These results (Table 3) corroborated visual inspections of bacterial plate cultures supplemented with chromogenic X-Gluc. The hyq operon was specifically and strongly expressed in diazotrophic culture but strongly repressed either in the presence of added ammonium under air or in the presence of added 0.5 mM L-glutamine under reduced O2. As strain 66210 was only weakly induced (Table 3), hyq operon induction specifically required NIFA transcriptional activation.

Table 3. A caulinodans hyq operon expression; PhyqR β-glucuronidase reporter activity.

| Strain | Atmosphere | N-source(s) | ||

| N2 only | +5 mM NH4 + | +5 mM NH4 + | ||

| (atm = 78+%) | +05 mM L-glutamine | |||

| 66205 | 2% O2 | 1410±200 | 220±35 | <10 |

| 21% O2 | <10 | <10 | ||

| 66210 nifA | 2% O2 | 40±10 | 40±10 | <10 |

| 21% O2 | <10 | <10 | ||

nmol 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indole min−1 mg protein−1.

When the presumed hyq operon control region (immediately upstream from the hyqR coding sequence) was analyzed, the genetic signatures of an orthodox A. caulinodans nif operon were apparent (Fig. 2). A NifAbox element, serving as cis-acting site for NIFA transactivation, and a σ54N site, serving as cis-acting site for RNA polymerase complexed with σ54N initiation factor, were both present and strategically positioned [22]. Thus, the A. caulinodans hyq operon control region likely binds NIFA, which activates hyq transcription via RNA polymerase · σ54N in response to both limiting physiological O2 and absence of fixed-N, as is observed for nifA autoregulation [22]. Accordingly, the A. caulinodans hyq operon is constituent of the nif regulon.

Discussion

In rhizobia, obligate oxidative bacteria, orthodox respiratory Ni,Fe-hydrogenase is encoded by contiguous hupSL genes. (In other obligate oxidative bacteria, orthologous gene assignments are variant, e.g. hoxKG in R. eutropha [12]). Notably, the Ni,Fe-catalytic center of this conserved respiratory hydrogenase complex is periplasmic-oriented, i.e. exo-hydrogenase. Indeed, orthologous rhizobial HupS and R. eutropha HoxK encoded FeS-center subunits possess a periplasmic export (RRxFxK) signal peptide motif [11]. Typical of H2-recycling rhizobia, the A. caulinodans exo-hydrogenase encoding genomic locus comprises a 21 kbp contiguous set of highly-conserved genes, among them hupSL [15] (Fig. 1). This respiratory hydrogenase activity is obviously adapted for use of exogenous H2.

Archetypal for the group-4 hydrogenases is E. coli hydrogenase-3, encoded by hycGE. This heterodimeric Ni,Fe-hydrogenase anchors an integral-membrane formate–hydrogen lyase complex, oxidizing formate to CO2 and reducing 2H+ to H2, all cell-internal, under strict, fermentative conditions [19]. In E. coli, a second group-4 hydrogenase (hydrogenase-4), encoded by the hyf operon, seems coupled to yet another fermentative formate dehydrogenase activity [18]. In Rhodospirillum rubrum a distinct, but related, group-4 hydrogenase activity is coupled to CO-dehydrogenase activity [23], [24]. In all cases these group-4 hydrogenases are active under anaerobic, strictly fermentative physiological conditions and so have been termed H2-evolving, simultaneously oxidizing either formate or CO to yield CO2 and reducing H+-ions to yield H2 (gas), all as fermentative end-products.

From multiple protein sequence alignments, the A. caulinodans HyqBCEFGI hydrogenase is a constituent member of the group-4 hydrogenases. However, as A. caulinodans, like all rhizobia, is an obligate oxidative (aerobic) bacterium and does not ferment, any metabolic role for H2 evolution is not obvious. Indeed, we have identified unlinked A. caulinodans genes encoding both formate- and CO-dehydrogenase activities; the former are orthologous to the aerobic, respiratory formate dehydrogenase of facultative bacteria such as E. coli; the CO-dehydrogenase genes are orthologous to the soluble, NAD-linked activities of obligate aerobic bacteria (data not presented).

From bacterial genome searches, orthologous hyq operons are evident in two additional rhizobial species, R. leguminosarum and B. japonicum both previously classified phenotypically as H2 recyclers [9], [25]. In the non-symbiotic but very closely related species Xanthobacter autotrophicus Py2 [26], an orthologous hyq operon is also present, as is the complete nif regulon, implying X. autotrophicus Py2 is also diazotrophic. All such bacteria carrying the hyq operon are obligate oxidative, in which any H2-evolving hydrogenase activities would seem not only superfluous but antithetical.

Metabolic roles for the group-4 hydrogenases are not definitive. All show integral-membrane components with homology to NADH : quinone dehydrogenase (respiratory complex I), which functions as unidirectional NADH oxidant and membrane quinone pool reductant [11], [18], [19]. Included in this homology are the heterodimeric Ni,Fe-hydrogenase subunits of group-4 hydrogenases (the A. caulinodans HyqGI proteins) which are closely related to the 49 kDa (Nqo4) and 20 kDa (Nqo6) subunits of the Thermus thermophilus (hyperthermophile) respiratory NADH-DH L1 sub-complex, whose crystal structure has been solved by X-ray diffraction at atomic resolution [27]. By structural analogy and genetic homology to the NADH-DH L1 sub-complex then, the homologous HyqGI heterodimeric endo-hydrogenase, with its active site facing cell-internally, likely interacts with the integral-membrane, L0-homologous HyqBCEF sub-complex and together function as H2 oxidant and membrane quinone reductant. Like both NADH-DH complex and E. coli hydrogenase-4, A. caulinodans Hyq endo-hydrogenase activity is presumably proton-motive, energy-conserving [18] and thus likely drives aerobic respiration. From multiple protein alignments including sequences identified in the four aerobic bacteria (A. caulinodans, B. japonicum, R. leguminosarum, X. autotrophicus), together with the E. coli HyfGI proteins, the endo-hydrogenase peripheral HyqG large-subunit carries the Ni,Fe-hydrogenase catalytic center and the HyqI small-subunit carries the (N2) proximal 4Fe–4S center as likely electron-donors to membrane-bound quinones.

Given this inferred organization and integral-membrane orientation of the Hyq endo-hydrogenase complex (for which we as yet lack direct experimental evidence), one implication is obvious: the Hyq endo-hydrogenase might physically interact with Mo-dinitrogenase so as to channel evolved H2 as substrate for membrane-driven respiration and oxidative phosphorylation. Coupled respiration would allow quantitative recovery of ATP consumed by Mo-dinitrogenase complex activity in H2 synthesis (and activation of N2 reduction to ammonium) [3], [4]. The group-4 hydrogenases of anaerobes, while quite possibly active in vivo in H2 evolution during strictly fermentative metabolism, nevertheless remain capable of H2 oxidation, albeit slowly [11]. Because Mo-dinitrogenase complex activity has exceedingly slow in vivo turnover (<10 sec−1), any directly coupled Hyq endo-hydrogenase H2 oxidizing activity might operate at correspondingly very slow rates in vivo.

H2-oxidative endo-hydrogenase activity necessitates that H+ ions be membrane-translocated else deplete the cell membrane proton-motive force. Any endo-hydrogenase driven, vector H+ translocation, an energy-requiring process, would be necessarily slow by comparison with exo-hydrogenase activity, uncoupled from H+ translocation, and thus relatively fast. (In the latter case, as H+ ions are produced external to the cell membrane, they in principle contribute directly to the cell membrane proton-motive force.) Thus, exo-hydrogenase activity is kinetically preferred as agent for exogenous H2 oxidation. By contrast, endo-hydrogenase activity, via metabolic channeling, might confer an increased efficiency of endogenous H2 recycling, thus mitigating energy loss, were such H2 to escape to the environment by simple diffusion.

Hydrogen has elicited considerable interest as potential renewable energy source for human civilization. If hydrogen is to be produced at scale as part of a sustainable cycle, external energy source(s) are then required. Solar energy represents an obvious energy coupling source, in principle allowing photoelectron transport and H2-evolving hydrogenase activities to operate as an integrated biocatalytic process in photosynthetic membranes. Accordingly, the reversible group-4 hydrogenases, such as the A. caulinodans Hyq endo-hydrogenase, offer particular promise as biocatalytic agents for hydrogen production and/or consumption.

Methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS571 wild-type (strain 57100), originally isolated from Sesbania rostrata stem-nodules [1], was cultured in both rich (SYPC) and miminal, defined media as previously described [14]. As 57100 wild-type is NAD auxotrophic, defined growth media must be supplemented with nicotinate (or similar) as precursor. However, nicotinate serves strain 57100 as both anabolic (for NAD production) and catabolic (as both utilizable C- and N-source) supplement. When strain 57100 is cultured in media with limiting primary C- and/or N-sources, nicotinate is rapidly catabolized and exhausted cultures quickly become NAD- limited for growth [28]. Accordingly, to eliminate nicotinate catabolism as a metabolic variable, all experiments reported herein employ A. caulinodans 61305R, a 57100 derivative carrying an IS50R insertion in the (catabolic) nicotinate hydroxylase structural gene, as “virtual” wild-type; 61305R only uses nicotinate as anabolic substrate and thus requires minimal (1 µM) nicotinate supplementation in all defined media [29].

Genetic constructions

A. caulinodans in-frame translational fusion mutants

Precise, in-frame deletion mutagenesis of the A. caulinodans hupSL genes was carried out by “crossover PCR” as previously described [13]. In the first step, separate ∼1 kbp genomic fragments immediately proximal to hupS and distal to hupL coding sequences were PCR amplified [13]. These two, ∼1 kbp amplified genomic fragments shared an artificial, complementary “crossover” sequence introduced by 21 bp extension of PCR primers “B” and “C” (Fig. 1). In a second-round PCR, the two amplified DNA fragments were purified, mixed, and used as combination primer-template. A ∼2 kbp DNA fragment was then produced when non-homologous template strands annealed via complementary 21 bp extensions; when an upstream coding-strand annealed to a downstream non-coding strand via the 21 bp crossover extension, 3′-ends on both annealed strands were extended by thermostable DNA polymerase yielding a contiguous ∼2 kbp DNA fragment in which the 21 bp crossover sequence fused the ∼1 kbp upstream and downstream sequences. In this second-round PCR, terminal “A” and “D” oligodeoxynucleotides (Fig. 1) were also included as primers such that, by standard recursive PCR, this ∼2 kbp crossover DNA fragment was further amplified. By design, the 21 bp crossover within the ∼2 kbp DNA fragment fuses in-frame an upstream target gene's translational “start” codon with a downstream target gene's “stop” codon yielding a translational (e.g., hupΔSL) fusion (Fig. 1).

The PCR amplified, crossover DNA fragment carrying the in-frame ∼2 kbp hupΔSL2 fusion allele was verified by DNA sequencing and introduced into the EcoRI site of plasmid pSUP202 (Table 1) by standard molecular cloning; E. coli strain MH3000 (Table 1) was subject to electroporation with recombinant plasmids, and transformed bacterial colonies were selected for tetracycline (Tc) resistance. In this manner, recombinant plasmid pHupΔSL2 was identified (Table 1), purified, and reintroduced by electroporation into E. coli SM10 (Table 1), proficient as donor for bacterial conjugation, again selecting for Tc-resistance. To allow plasmid conjugal transfer, E. coli SM10/pHupΔSL2 as donor was mixed with A. caulinodans 61305R as recipient and plated overnight on SYPC solid medium at 37°C. Conjugal cell mixtures were then selectively plated on solid ORSMM (to counter-select E. coli) supplemented with Tc (10 µg/ml) at 37°C. As parental plasmid pSUP202 cannot stably replicate in A. caulinodans, transconjugants that are stably Tc-resistant arise after homologous, single recombination events in which the entire plasmid and the target genome are cointegrated [22]. Accordingly, A. caulinodans 61305R hupSL merodiploids were then isolated and confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing analyses; such strains carried both genomic hupS+L+ and hupΔSL2 alleles bridged by the integrated SUP202 sequence. To then isolate haploid gene-replacement strains, merodiploids were subcultured absent Tc selection in rich GYPC liquid medium and then plated with Tc added at very low (0.125 µg/ml) levels sufficient to 50% inhibit growth of parental wild-type. Pinpoint colonies were identified, retested, and a Tc-sensitive phenotype verified. These putative haploid derivatives arose by a second, single homologous recombination (disintegration) event within the merodiploid, segregating the hupSL alleles. By PCR analysis with Hup-Prox and Hup-Dist as oligodeoxynucleotide primer-pair (Table 1; Fig. 1), resulting haploid strains showed either hupS+L+ or hupΔSL2 alleles.

Similarly, a haploid 61305R derivative carrying a complete hyqRBCEFGI in-frame deletion allele was isolated using the same crossover PCR technique. Recombinant plasmid pHyqΔRI7 carried a ∼2 kbp hyqΔRI7 allele in which the identical 21 bp linker fused in-frame the hyqR “start” codon with the hyqI “stop” codon (Table 1; Fig. 2). After gene replacement, haploid strain 66132 carrying the hyqΔRI7 allele was isolated and verified by PCR and DNA sequencing analyses.

A. caulinodans Hyq transcriptional reporter strains

To construct hyq merodiploid transcriptional reporter strains, a 1.8 kbp fragment carrying the E. coli uidA+ coding sequence was amplified by PCR using synthetic oligodeoxynucleotide primers extended with 6 bp SalI endonuclease recognition sequences (Table 1). As the 21 bp linker sequence used to construct in-frame translational fusions includes a SalI recognition sequence, plasmid pHyqΔRI7 was partially digested with SalI endonuclease, a 9.8 kbp DNA fragment was isolated, mixed with SalI digested, amplified 1.8 kbp uidA+ DNA fragment and recombinant plasmids were recovered by standard molecular cloning techniques. After electroporation of E. coli MH3000, and selection for Tc-resistance, uidA + recombinant plasmids were identified by plating candidate strains on minimal media supplemented with (0.1 mg ml−1) 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-glucuronide (XGluc), a chromogenic β-glucuronidase substrate, and screening for blue colonies. From PCR and DNA sequencing analysis, recombinant plasmid pHyqRU5 carrying the hyqR::uidA+ in-frame translational fusion allele was isolated (Table 1). Plasmid pHyqRU5 was introduced to E. coli SM10, and this strain was employed as conjugal donor with A. caulinodans 61305R and 60107R, and Tc-resistant derivatives were selected and isolated. Merodiploid strains 66205 and 66210 (Table 1) carrying both upstream hyqR::uidA+ hyqΔBI and downstream hyq+ operon were identified and verified by PCR and DNA sequencing analyses.

Physiological growth and β-glucuronidase activity measurements

Starter cultures of A. caulinodans strain 61305R and its derivatives were aerobically cultured in minimal defined NIF liquid medium [14] supplemented with: ammonium (0.5 mM) as sole, limiting N-source and 1 uM nicotinate at 37°C until growth arrested (cell densities ∼1×108 cells ml−1). For kinetic measurements of diazotrophy, arrested starter cultures were diluted one-thousandfold in NIF medium (with 1 uM added nicotinate) into 30 ml serum vials, sealed with silicone rubber septa, sparged continuously (6 ml min−1) with defined gas mixtures (e.g. 2% O2, 5% CO2, bal. N2), and incubated at 29°C. At least three times per cell-doubling period, culture samples were removed, serially diluted, plated on rich GYPC medium [14], incubated 48 hr at 37°C, and colonies were counted, in triplicate. β-glucuronidase activity was measured with as chromogenic substrate 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-glucuronide (X-Gluc) [30]; total protein concentrations were determined in a folin phenol reagent assay [31]. All induction experiments were conducted in triplicate and were repeated until the standard error in β-GUS activities was below 15%.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bruce Roe for providing an A. caulinodans ORS571 shotgun partial genome sequence library, Robert Baertsch and Todd Lowe for help in genome assembly, and Derek McCusker, Chad Saltikov, and Julie Murphy for PCR troubleshooting. The GenBank accession number for the sequence reported in this paper is FJ378904.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work is funded by the University of California Energy Institute. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Dreyfus BL, Dommergues YR. Nitrogen fixing nodules induced by Rhizobium on strains of the tropical legume Sesbania rostrata. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1981;10:313–317. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott JD, Ludwig RA. Azorhizobium caulinodans electron-transferring flavoprotein N electrochemically couples pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity to N2 fixation. Microbiology. 2004;150:117–126 (2004). doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26603-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thorneley RNF, Lowe DJ. In: Molybdenum enzymes. Spiro TG, editor. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1985. pp. 221–284. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgess BK, Lowe DJ. Mechanism of molybdenum nitrogenase. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2983–3011. doi: 10.1021/cr950055x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burris RH, Arp DJ, Benson DR, Emerich DW, Hageman RV, et al. The biochemistry of nitrogenase, In: Stewart WDP, Gallon JR, editors. Nitrogen Fixation. London: Academic Press; 1980. pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyndman LA, Burris RH, Wilson PW. Properties of hydrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii. J Bacteriol. 1953;65:522–531. doi: 10.1128/jb.65.5.522-531.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phelps AS, Wilson PW. Occurrence of hydrogenase in nitrogen-fixing organisms. Proc Soc Exp Biol. 1941;47:473–476. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith L, Hill S, Yates MG. Inhibition by acetylene of conventional hydrogenase in nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Nature. 1976;262:209–210. doi: 10.1038/262209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon ROD. Hydrogenase in pea root nodule bacteroids: occurrence and properties. Arch Mikrobiol. 1972;85:193–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00408844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vignais PM, Billoud B. Occurrence, classification, and biological function of hydrogenases: an overview. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4206–4272. doi: 10.1021/cr050196r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vignais PM, Billoud B, Meyer J. Classification and phylogeny of hydrogenases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2001;25:455–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernhard M, Benelli B, Hochkoeppler A, Zannoni D, Friedrich B. Functional and structural role of the cytochrome b subunit of the membrane-bound hydrogenase complex of Alcaligenes eutrophus H16. Eur J Biochem. 1997;248:179–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Link AJ, Phillips D, Church GM. Methods for generating precise deletions and insertions in the genome of wild-type Escherichia coli: application to open reading frame characterization. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6228–6237. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6228-6237.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donald RGK, Nees D, Raymond CK, Loroch AI, Ludwig RA. Three genomic loci encode [Azo]Rhizobium sp. ORS571 N2 fixation genes. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:72–81. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.1.72-81.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baginsky C, Palacios JM, Imperial J, Ruiz-Argueso T, Brito B. Molecular and functional characterization of the Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS571 hydrogenase gene cluster. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;237:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burgdorf T, Lenz O, Buhrke T, van der Linden E, Jones AK, et al. [NiFe]-hydrogenases of Ralstonia eutropha H16: modular enzymes for oxygen-tolerant biological hydrogen oxidation. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;10:181–196. doi: 10.1159/000091564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kent WJ. BLAT–the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrews SC, Berks BC, McClay J, Ambler A, Quail MA, et al. A 12-cistron Escherichia coli operon (hyf) encoding a putative proton-translocating formate hydrogenlyase system. Microbiology. 1997;143:3633–3647. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-11-3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Böhm R, Sauter M, Böck A. Nucleotide sequence and expression of an operon in Escherichia coli coding for formate hydrogenlyase components. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:231–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee K-B, De Backer P, Aono T, Liu C-T, Suzuki S, et al. The genome of the versatile nitrogen fixer Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS571. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:271. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ludwig RA. Microaerophilic bacteria transduce energy via oxidative metabolic gearing. Res Microbiol. 2004;155:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loroch AI, Nguyen B, Ludwig RA. FixLJK and NtrBC signals interactively regulate Azorhizobium nifA transcription via overlapping promoters. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7210–7221. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7210-7221.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox JD, He Y, Shelver D, Roberts GP, Ludden PW. Characterization of the region encoding the CO-induced hydrogenase of Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6200–6208. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6200-6208.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fox JD, Kerby RL, Roberts GP, Ludden PW. Characterization of the CO-induced, CO-tolerant hydrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum and the gene encoding the large subunit of the enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1515–1524. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.6.1515-1524.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schubert KR, Evans HJ. Hydrogen evolution: A major factor affecting the efficiency of nitrogen fixation in nodulated symbionts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:1207–1211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.4.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Copeland A, Lucas S, Lapidus A, Barry K, Glavina del Rio T, et al. 2007. Complete sequence of chromosome of Xanthobacter autotrophicus Py2, Submitted to the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ databases.

- 27.Sazanov LA, Hinchcliffe P. Structure of the hydrophilic domain of respiratory complex I from Thermus thermophilus. Science. 2006;311:1430–1436. doi: 10.1126/science.1123809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludwig R. [Azo]Rhizobium sp ORS571 grows synergistically on N2 and nicotinate as N-sources. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:304–307. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.1.304-307.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buckmiller LM, Lapointe JP, Ludwig RA. Physical mapping of the Azorhizobium caulinodans nicotinate catabolism genes and characterization of their importance to N2 fixation. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2017–2025. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.2017-2025.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jefferson RA. Assaying chimeric genes in plants: the Gus fusion system. Plant Molec Biol Rep. 1987;5:387–405. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peterson GL. Review of the Folin phenol protein quantitation method of Lowry, Rosebrough, Farr and Randall. Anal Biochem. 1979;10:101–220. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinstock GM, ap Rhys C, Berman ML, Hampar B, Jackson D, et al. Open reading frame expression vectors: a general method for antigen production in Escherichia coli using protein fusions to β-galactosidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:4432–4436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.14.4432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram− bacteria [Nature]. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]