Abstract

The fully oxidized form of cytochrome c oxidase, immediately after complete oxidation of the fully reduced form, pumps protons upon each of the initial 2 single-electron reduction steps, whereas protons are not pumped during single-electron reduction of the fully oxidized “as-isolated” form (the fully oxidized form without any reduction/oxidation treatment) [Bloch D, et al. (2004) The catalytic cycle of cytochrome c oxidase is not the sum of its two halves. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:529–533]. For identification of structural differences causing the remarkable functional difference between these 2 distinct fully oxidized forms, the X-ray structure of the fully oxidized as-isolated bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase was determined at 1.95-Å resolution by limiting the X-ray dose for each shot and by using many (≈400) single crystals. This minimizes the effects of hydrated electrons induced by the X-ray irradiation. The X-ray structure showed a peroxide group bridging the 2 metal sites in the O2 reduction site (Fe3+-O−-O−-Cu2+), in contrast to a ferric hydroxide (Fe3+-OH−) in the fully oxidized form immediately after complete oxidation from the fully reduced form, as has been revealed by resonance Raman analyses. The peroxide-bridged structure is consistent with the reductive titration results showing that 6 electron equivalents are required for complete reduction of the fully oxidized as-isolated form. The structural difference between the 2 fully oxidized forms suggests that the bound peroxide in the O2 reduction site suppresses the proton pumping function.

Keywords: hydrated electron, O2 reduction mechanism, membrane protein, X-ray structural analysis, cell respiration

Cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) is a key component of the respiratory chain that catalyzes dioxygen reduction coupled with a proton-pumping process. The O2 reduction site includes a high-spin heme A (heme a3) and a copper ion (CuB) with 3 histidine imidazoles as the ligands (1). Cyanide has been used to probe the properties of the oxygen-binding site. Three types of the fully oxidized forms have been reported showing different cyanide binding rates, namely, “slow,” “fast,” and “open” forms (2, 3). The rate of cyanide binding to the open form is 5 orders of magnitude higher than the binding rate to the fast form (4). The latter is still significantly higher than the binding rate to the slow form. The slow and fast forms have Soret maxima at 418 and 423 nm, respectively, in the fully oxidized “as-isolated” enzyme, depending on the purification procedure (2), whereas the open form appears during the catalytic turnover (4). Six electron equivalents are required for complete reduction of the fast form (5). Each of the first and second single-electron donations to the fully oxidized enzyme, immediately after O2 oxidation of the fully reduced enzyme (corresponding to the open form), induces proton pumping, whereas single-electron reduction of the fully oxidized as-isolated form (the fully oxidized form without any reduction/oxidation treatment, the slow or fast form) does not induce proton pumping (6). The structural differences in the O2 reduction site between these 2 types of the fully oxidized form are expected to provide important clues for elucidation of the proton pumping mechanism.

The iron coordination structure of the O2 reduction site (Fea3) of the fully oxidized enzyme, immediately after O2 oxidation of the fully reduced enzyme, is likely to be Fe3+-OH− as shown by resonance Raman analyses of the O2 oxidation process of the fully reduced enzyme (7). On the other hand, the chemical structures of the O2 reduction site of the fully oxidized as isolated forms have not been established despite various spectral and structural analyses (8). Extensive EPR measurements indicate the presence of a magnetic coupling between Fea33+ and CuB2+. An oxide ion or a chloride ion has been proposed as the bridging ligand between the 2 metals. However, the technique does not provide any direct structural information with regard to the ligand structure (8, 9). No resonance Raman evidence for the structure has been reported because of the high photosensitivity of the as isolated form for usual resonance Raman experimental conditions. On the other hand, several X-ray structural analyses have been reported for bacterial and bovine heart CcO. The X-ray structures of cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus determined at 2.3-Å (10) and 2.4-Å (11) resolution indicate the presence of a water molecule between Fea3 and CuB. Ostermeier et al. (12) and Qin et al. (13) identified a water molecule bound to the heme a3 iron and a hydroxide anion bound to CuB. An additional structural analysis of a bacterial cytochrome oxidase did not provide a precise structure between Fea3 and CuB (14).

The X-ray structures of the fully oxidized as isolated form, however, are not consistent with each other. [The purification method for bovine heart CcO provides the fast form as the fully oxidized as-isolated form (5).] At 2.3-Å resolution, a peroxide group was assigned as a bridging ligand between Fea3 and CuB in the electron density map of the bovine enzyme (15) whereas at 1.8-Å resolution, the electron density between the 2 metal sites was too low to locate 1 peroxide group (16). The 2.3-Å resolution analysis of the bovine enzyme was performed by using 32 crystals at ambient temperature, whereas the 1.8-Å resolution analysis was performed by using 2 crystals at 100 K. We expected that the X-ray dose would induce reduction of the heme iron to provide a concomitant structural change in the O2 reduction site in the 1.8-Å resolution structure, as previously reported for X-ray reduction of the heme iron of peroxidase (17). The radiation dose used for the 1.8-Å-resolution analysis was much higher than that of the 2.3-Å-resolution analysis. On the other hand, we expect that, under X-ray diffraction experiments at room temperature under aerobic conditions, CcO in the crystals undergoes turnover conditions instead of remaining in the fully oxidized as-isolated state. Furthermore, the effects of X-ray irradiation on the absorption spectra of the enzyme crystals were poorly evaluated, because the improved spectrophotometer used in the present work was not yet available. Therefore, the electron density distribution between the 2 metals in the O2 reduction site, obtained previously at 281 K (15), should be regarded as a preliminary result.

Therefore, we decided to reexamine the X-ray structure of the fully oxidized as-isolated bovine heart CcO by minimizing X-ray irradiation effects at 100 K. This is accomplished by using many crystals instead of repeating many measurements using the same crystal. The X-ray structure under the conditions described is essentially free from the influence of the hydrated electrons. This structure at 1.95-Å resolution shows a peroxide group bridging the Fea3 and CuB ions.

Results

Absorption Spectral Changes Induced by X-Ray Irradiation at 100 K.

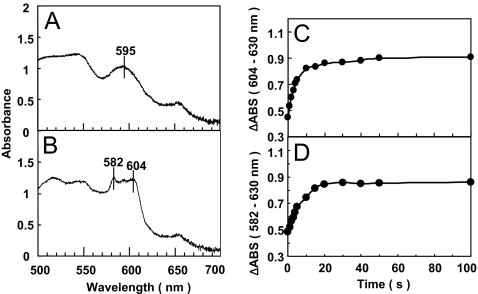

Irradiation of the fully oxidized as-isolated CcO crystals with X-rays at a photon flux of 2 × 1014 photons sec−1 mm−2 induced significant absorbance increases at 604 and 582 nm with half-lives (t1/2) of 3.0 and 4.0 s, respectively. The maximal intensity is observed at ≈20 s, as shown in Fig. 1. The spectrum is clearly different from that of CcO crystals after complete reduction of the fully oxidized as-isolated crystals at ambient temperature. The absorbance changes induced by X-ray irradiation were found to be approximately proportional to the radiation dose provided within the initial 7.5 s. No further significant spectral changes were detectable, although the resulting spectrum is clearly different from that of the fully reduced form. However, after the crystals that were subjected to X-ray irradiation for 20 s or longer at 100 K were exposed to room temperature for a few seconds followed by rapid refreezing under N2 gas flow at 100 K, the absorption spectrum of the fully reduced CcO was obtained. The X-ray irradiation did not induce any detectable spectral changes in the frozen crystals of the fully reduced enzyme. These results strongly suggest that the spectral changes of the fully oxidized as-isolated CcO induced by X-ray irradiation are due to reduction of the metal sites by hydrated electrons created by the strong X-ray beam and not due to damage or structural changes of the hemes.

Fig. 1.

Effects of X-ray irradiation on the visible absorption spectra of the single crystals of the fully oxidized “as isolated” bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. The measuring light beam focused to ≈50 μm in diameter was injected perpendicularly to the most extended plane of (010). The X-ray beam injected along the plane was thick enough to irradiate the entire area of the crystals that was irradiated with the measuring light beam. (A and B) The visible spectra are shown for the sample before the X-ray irradiation (A) and after a 30-second exposure (B). (C and D) Time courses of increases in absorption difference are shown between 604 and 630 nm (C) and between 582 and 630 nm (D).

As shown in Fig. 1, the effect of X-ray irradiation caused by use of the third generation synchrotron radiation facility (SPring-8), which produces high-density hydrated electrons, was unexpectedly strong for cytochrome c oxidase, which contains metal sites with high redox potentials. The improvement of our custom-built spectrophotometer for selective measurement of the absorbance spectrum of the irradiated area of the crystals was critical for quantitative evaluation of the X-ray irradiation effects.

Examination of X-Ray Structural Changes Coupled to the Absorption Spectral Changes Induced by X-Ray Irradiation at 100 K.

To examine the X-ray structural changes that occur during the absorbance changes induced by X-ray irradiation, X-ray diffraction experiments were conducted. The cross-section of the X-ray beam (0.9 Å) was 50 μm × 50 μm. The beam size was adjusted by a slit system without focusing the X-ray beam. The size of crystals used for this experiment was ≈500 × 500 × 200 μm. Each shot was obtained at a fresh position of the crystal in 1- or 15-s exposures. A total of 190 crystals were used for the 1-s experiment, and 201 crystals were used for the 15-s experiments. Furthermore, the crystal was translated by 100 μm during a 0.6° rotation to reduce the X-ray exposure time. Thus, the X-ray data obtained from the 2 experiments correspond to those obtained by X-ray exposures of 0.33 and 5 s for each shot, respectively. The absorption change in Fig. 1 indicates that ≈4% and 60% of the maximal absorbance increases are induced during these exposures. Intensity data were processed by using the CCP4 program MOSFLM (18) and scaled by using SCLONE (19), which was developed by us for diffraction images with no serial oscillation angle.

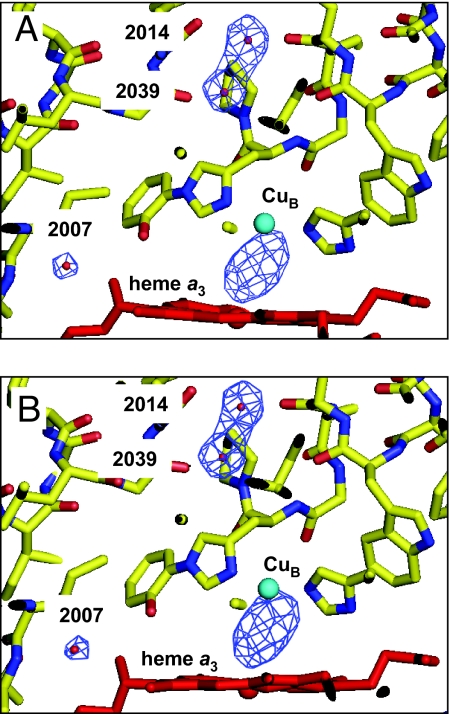

The 1- and 15-s-exposure experiments provided 2.5-Å and 2.1-Å datasets, respectively. Statistics of intensity datasets and structural refinements are given in the supporting information (SI). The r.m.s. deviation of backbone atoms between the 2 refined structures was 0.16 Å, indicating that there are no significant structural differences. The (Fo-Fc) difference electron density maps for the 1- and 15-s datasets, calculated at 2.5-Å resolution, are given in Fig. 2. In the difference maps of the 1- and 15-s data, the peak heights between Fea3 and CuB were 1.64 and 1.67 times the averaged peak height for 3 reference water molecules located near the O2 reduction site (2,007, 2,014, and 2,039 in Fig. 2). Statistics of peak heights of the electron densities between Fea3 and CuB are given in the SI. The electron densities between the 2 metals in both difference maps were almost identical to each other in their shape and peak height relative to the average peak height of the reference water molecules. The results indicate that the electron density distribution between the 2 metals remains unchanged during the 15-s X-ray irradiation experiments at 100 K, which gives an average irradiation time of 5 s.

Fig. 2.

(Fo-Fc) difference electron density maps for the 1- s and 15-s datasets, calculated at 2.5-Å resolution. The datasets are depicted together with the structural model of heme a3, CuB, and 3 water molecules. Heme a3, CuB, and the oxygen atom of each of the water molecules are colored in red, green, and light blue, respectively. Three water molecules, 2,007, 2,014 and 2,039, were not included in the structural refinements performed to compare their electron densities with the electron density between Fea3 and CuB. (A) The cages of the difference map for the 1-s data are drawn at the 4.5σ level. (B) The cages for the 15-s data are drawn at the 5σ level.

Structure of the O2 Reduction Site Determined at 2.1-Å Resolution from the 15-s Dataset.

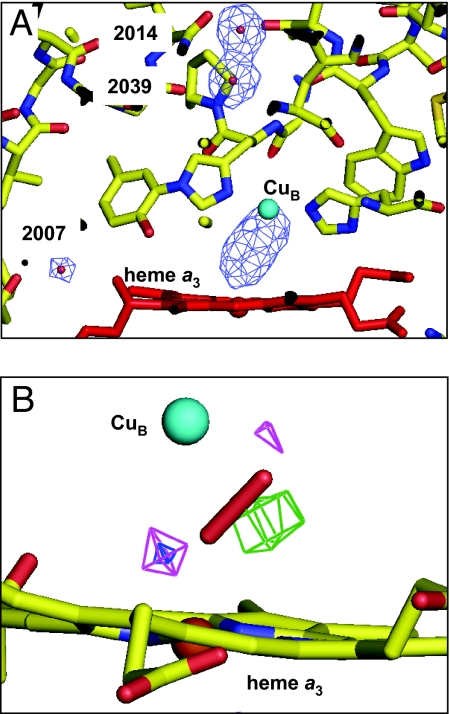

An electron density peak equivalent to that of 2 separate oxygen atoms was detected in a difference electron density map at 2.1-Å resolution (Fig. 3A). The peak of the electron density between the metal centers was 1.55 times higher than that of the average peak height of 3 reference water molecules. The electron density distribution between the 2 metal ions had the shape of an elongated ellipsoid, whereas 2 water molecules separated by 2.8 Å gave the 2 different peaks labeled “2014” and “2039” in Fig. 3A. The structure between the 2 metals was refined under constraint of the O O distance to 1.6, 1.7, and 1.8 Å. The soundness of refinements was evaluated by residual electron density around the 2 oxygen atoms for determination of the O

O distance to 1.6, 1.7, and 1.8 Å. The soundness of refinements was evaluated by residual electron density around the 2 oxygen atoms for determination of the O O distance (Fig. 3B). The residual electron density of the refinement with the O

O distance (Fig. 3B). The residual electron density of the refinement with the O O distance of 1.7 Å was the lowest among the 3 refinement results. Structural refinement without any constraints on the O

O distance of 1.7 Å was the lowest among the 3 refinement results. Structural refinement without any constraints on the O O distance resulted in an O

O distance resulted in an O O distance of 1.9 Å. The difference electron density map with this distance, however, had larger residual densities at the O2 reduction site when compared with the refinement under constraint of the O

O distance of 1.9 Å. The difference electron density map with this distance, however, had larger residual densities at the O2 reduction site when compared with the refinement under constraint of the O O distance. Consequently, a peroxide group with an O

O distance. Consequently, a peroxide group with an O O distance of 1.7 Å is the most appropriate assignment to the electron density between Fea3 and CuB. The coordination bond of Fea3-O is essentially perpendicular to the heme plane. Other bond distances and angles are given in Fig. 4. The Fea3-O bond length is significantly longer than that of the typical low-spin coordination. This observation is consistent with the high-spin state of Fea3 as previously suggested (8).

O distance of 1.7 Å is the most appropriate assignment to the electron density between Fea3 and CuB. The coordination bond of Fea3-O is essentially perpendicular to the heme plane. Other bond distances and angles are given in Fig. 4. The Fea3-O bond length is significantly longer than that of the typical low-spin coordination. This observation is consistent with the high-spin state of Fea3 as previously suggested (8).

Fig. 3.

(Fo-Fc) difference electron density map of the 15-s data calculated at 2.1-Å resolution. (A)Electron density cages for the electron density between and Fea3 and CuB, and for 3 water molecules depicted at the 5.2σ level in a stick model around the O2 reduction site. Carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms are colored in yellow, blue, and red, respectively. (B) (Fo-Fc) difference maps for the 15-s dataset obtained under 3 different constraints on the O O distance. Cages are depicted at the 3.8σ level. Heme a3 is depicted by a ball-and-stick model. Carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms are yellow, blue, and red, respectively. The peroxide anion is illustrated by a stick model. Fea3 and CuB are represented in brown and green. The map of the 1.6-Å constraint (pink) has residual density peaks at both ends of the O

O distance. Cages are depicted at the 3.8σ level. Heme a3 is depicted by a ball-and-stick model. Carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms are yellow, blue, and red, respectively. The peroxide anion is illustrated by a stick model. Fea3 and CuB are represented in brown and green. The map of the 1.6-Å constraint (pink) has residual density peaks at both ends of the O O bond, whereas the map of the 1.8-Å constraint (green) has a large residual density at the middle of the O

O bond, whereas the map of the 1.8-Å constraint (green) has a large residual density at the middle of the O O bond. The cages for the 1.7-Å constraint (blue) have the smallest residual density.

O bond. The cages for the 1.7-Å constraint (blue) have the smallest residual density.

Fig. 4.

Coordination geometries of the peroxide anion obtained from structural refinement of the 15-s dataset calculated at 2.1-Å resolution. The interatomic distances are given in angstroms. Other distances and angles are Fea3-CuB, 4.87 Å; Nε2(H376)- Fea3-O1, 168.5°; Fea3-O1-O2, 144.1° and O1-O2-CuB, 90.5°. These geometries are fully consistent with those of the X-ray structure determined from the 103.5-s exposures at 1.95-Å resolution.

Chloride ions cannot be fitted into the electron density between the 2 metals in the O2 reduction site. Furthermore, chloride analyses of the crystalline CcO with ICP emission spectrometry indicate that chloride is not detectable in the enzyme preparation used for the present investigation.

Effect of Excessive X-Ray Irradiation on the Structure of the O2 Reduction Site at 100 K.

The structural changes induced by X-ray irradiation periods of >100 s were examined as follows; 5 crystals were used to prepare 20 serial datasets. X-rays were irradiated at each position for 594 s in total without any translation. Each crystal was shot at 4 different positions. The exposure period of each shot was 9 s, and the oscillation angle was 0.3°. A serial experiment consisted of 66 sequential images. A total of 1,320 images were recorded from 5 crystals. Processing and scaling of images were performed by using DENZO and SCALEPACK (20), respectively. Three datasets, with exposure periods of 9–198 s, 207–396 s, and 405–594 s, were created by merging images 1–22, 23–44, and 45–66.

The structural refinement with the dataset from the 9- to 198-s exposure was performed at 1.95-Å resolution. The refinement statistics are listed in the SI. Difference electron density maps for Fo (9–198 s) − Fo (207–396 s) and Fo (9–198 s) − Fo (405–594 s) give electron density differences induced by the average of the exposures for 198 and 396 s, respectively, to the crystals after an average exposure of 103.5 s. These electron density maps were calculated with the refined phase angles from the 9- to 198-s dataset. The (Fo-Fc) difference electron density of the 9- to 198-s data had a peak of 0.42 e−/Å3 for the peroxide group. Two serial Fo-Fo difference maps showed that the electron density of the peroxide group decreased by 0.08 e−/Å3 (19.0%) in the 198-s exposure and 0.12 e−/Å3 (28.6%) in the 396-s exposure. The rate constant for peroxide reduction in the crystalline state, calculated from the electron density decrease, assuming a monophasic exponential decrease, was found to be 0.85 × 10−3 ≈ 1.1 × 10−3 s−1(or t1/2, 0.82 × 103 ≈ 0.63 × 103 s). No significant structural difference of the peroxide group (with the exception of its B-factor) is detectable between the 3 X-ray structural refinements. The electron density of the peroxide group extrapolated to a 0-s exposure should show a slightly higher intensity (≈10%) but essentially the same shape as that for the average exposure of 103.5 s, which is consistent with that determined from the 15-s dataset within the experimental accuracy. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the X-ray structure determined for the 103.5-s exposure at 1.95-Å resolution shows the structure of the peroxide before X-ray irradiation. This conclusion has been confirmed by an analogous investigation at 30 K that indicated that no significant change occurs in the distribution and intensity of the electron density of the peroxide group after the X-ray irradiation for as long as 400 s. The much slower rate of reduction of the bridging peroxide to hydroxide ions compared with the absorption spectral changes given in Fig. 1 indicates that reduction of the bridging peroxide is coupled to conformational changes that are significantly restricted at 100 K.

Another (Fo-Fc) map for the 405- to 594-s dataset was calculated at 1.95-Å resolution. This difference map given in the SI shows that an electron density peak arises near the hydroxide group of Tyr-244. The (Fo-Fc) difference electron density map together with the above (Fo-Fo) difference maps indicates that a water molecule generated by reduction of the peroxide is transferred to Tyr-244 to form a hydrogen bond with the hydroxyl group of Tyr-244.

Discussion

Structure and Stability of the Ligand Bridging the 2 Metals in the O2 Reduction Site of the Fully Oxidized as-Isolated Form of Bovine Heart Cytochrome c Oxidase.

A total of 48 non-protein-derived peroxide structures that bridges 2 metal ions are currently included in the Cambridge Structural Database. The average O O distance in these structures is 1.444 ± 0.058 Å. The recently reported O

O distance in these structures is 1.444 ± 0.058 Å. The recently reported O O distances of bound peroxide detectable in high-resolution X-ray structures of hemoproteins (determined at <1.9-Å resolution) are between 1.28 and 1.49 Å (21–23). An O

O distances of bound peroxide detectable in high-resolution X-ray structures of hemoproteins (determined at <1.9-Å resolution) are between 1.28 and 1.49 Å (21–23). An O O bond distance of 1.7 Å is thus significantly longer than the length of a typical O

O bond distance of 1.7 Å is thus significantly longer than the length of a typical O O single bond. On the other hand, the distance is too short to assign the electron density to 2 separate hydroxyl groups hydrogen bonded to each other. In fact, the shortest O

O single bond. On the other hand, the distance is too short to assign the electron density to 2 separate hydroxyl groups hydrogen bonded to each other. In fact, the shortest O O distance in the hydrogen bonding structure, deposited in the Cambridge Database is 2.4 Å. Furthermore, 2 oxides that bridge 2 metal ions, as in the case of a typical bis (μ-oxo) dicopper complex, have an oxygen interatomic distance of 2.3–2.5 Å (24). Therefore, the bond length is strongly suggestive of the presence of a covalent bond between the 2 oxygen atoms.

O distance in the hydrogen bonding structure, deposited in the Cambridge Database is 2.4 Å. Furthermore, 2 oxides that bridge 2 metal ions, as in the case of a typical bis (μ-oxo) dicopper complex, have an oxygen interatomic distance of 2.3–2.5 Å (24). Therefore, the bond length is strongly suggestive of the presence of a covalent bond between the 2 oxygen atoms.

The presence of the peroxide in the fully oxidized “as isolated” CcO is supported further by the reductive titration results showing that 6 electron equivalents are required for complete reduction of the fully oxidized as-isolated form of bovine heart CcO (5). In the reductive titration, the initial 2-electron reduction induces significantly smaller absorbance changes per electron equivalent added, relative to the changes occurring after addition of the subsequent 4 electron equivalents (5). The smaller absorbance changes suggest that the peroxide with high redox potential at the O2 reduction site accepts the initial 2-electron equivalents without changing the oxidation state of the metal sites. The 6-electron reduction excludes the possibility that the combination of O2 and a reversible 2-electron donor in the protein and O2 produces the bridging peroxide, because 8 electron equivalents are required for complete reduction of the O2-bound fully oxidized enzyme. Thus, an irreversible 2-electron donor is required for formation of the fast form. The possible electron donors are discussed in ref. 5.

It has been reported that the fully oxidized as-isolated form, which requires 6 electron equivalents for complete reduction, is regenerated over a time scale of a few minutes by extensive oxygenation of a preparation of the fully oxidized form that requires 4 electron equivalents for complete reduction. This fully oxidized form is prepared by titration of the fully reduced enzyme with a stoichiometric amount of O2 under anaerobic conditions. The slow rate of the regeneration also strongly suggests that the fully oxidized as-isolated form (namely, the peroxide-bound form) is not involved in the catalytic cycle as an intermediate species.

The long O O bond distance indicates that the peroxide group at the O2 reduction site is in a significantly activated state relative to those of other peroxide-bridged structures. Furthermore, the 2 electron equivalents for reduction of the bridging peroxide (which has an extremely high redox potential) could be readily available from Fea33+ and the OH group of Tyr-242 that is covalently bound to one of the imidazole ligands of CuB2+. Despite these structural features, the enzyme species containing this state of the O2 reduction site (the “fast” form) is extremely stable and can be stored in the crystalline state for more than 1 year at 4 °C without significant spectral changes. There are no visible structural features at the present time that rationalize the unusual stability.

O bond distance indicates that the peroxide group at the O2 reduction site is in a significantly activated state relative to those of other peroxide-bridged structures. Furthermore, the 2 electron equivalents for reduction of the bridging peroxide (which has an extremely high redox potential) could be readily available from Fea33+ and the OH group of Tyr-242 that is covalently bound to one of the imidazole ligands of CuB2+. Despite these structural features, the enzyme species containing this state of the O2 reduction site (the “fast” form) is extremely stable and can be stored in the crystalline state for more than 1 year at 4 °C without significant spectral changes. There are no visible structural features at the present time that rationalize the unusual stability.

Effect of X-Ray Irradiation on the Single Crystals of Cytochrome c Oxidase Using Synchrotron Radiation Facilities.

Most of the chemical reactions occurring in the interior of proteins that are coupled to protein conformational changes, are strongly but (not completely) suppressed at 100 K. Thus, most of the protein structures including conformations observable at room temperature are frozen at 100 K even under strong X-ray irradiation. However, as demonstrated in the present case of reduction of the peroxide, careful assessment of the X-ray irradiation is crucial for extrapolation to the room-temperature structure.

On the other hand, the low-temperature conditions could provide a unique strategy for investigation of the mechanism of the protein function, as indicated by the present results. The CcO crystals observed after X-ray irradiation for 20 s or longer did not exhibit spectra similar to those of the fully reduced CcO crystals, as shown in Fig. 1. The hemochrome-type spectrum with the sharp band with a peak at 582 nm, which resembles that of the CO-bound ferrous heme a3, strongly suggests that heme a3 is in a 6 coordinated low-spin ferrous state. The ligand is most likely to be a peroxide or a hydroperoxide. In other words, the reduction of heme a3 is not coupled to any conformational changes occurring in the protein moiety, whereas the electron transfer from heme a3 to the bound peroxide is coupled to a conformational change, which is blocked at 100 K. Therefore, the 582-nm peak in the spectrum shown in Fig. 1 has been observed only under the present conditions.

The previous results obtained at ambient temperature indicate that the O O bond length of the peroxide is 1.6 Å. This is similar to the present results obtained at 100 K, although the resolution of the previous X-ray structure is significantly lower than the structure obtained in this present investigation (2.3 Å vs. 1.95 Å). The results suggest that the conformational changes accompanied by the electron transfer from the metal sites to the bound peroxide are fairly restricted in the crystal lattice even at ambient temperature.

O bond length of the peroxide is 1.6 Å. This is similar to the present results obtained at 100 K, although the resolution of the previous X-ray structure is significantly lower than the structure obtained in this present investigation (2.3 Å vs. 1.95 Å). The results suggest that the conformational changes accompanied by the electron transfer from the metal sites to the bound peroxide are fairly restricted in the crystal lattice even at ambient temperature.

The excessive X-ray irradiation experiment showed that Tyr-244 accepts a water molecule generated by reduction of the peroxide by forming a hydrogen bond (SI). The results suggest that Tyr-244 functions as a scavenger of water molecules in the protein interior space that includes the O2 reduction site. In other words, if a water molecule is not hydrogen-bonded to Tyr-244 OH group, the presence of water molecules in the interior space is unlikely. X-ray structures of bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase determined thus far, with the exception of the present results, do not indicate a water molecule at Tyr-244. The protein interior space is large enough to accept several water molecules. Therefore, various reaction mechanisms of this enzyme have been proposed that assume the presence of water molecules within the interior space without any positive experimental evidence (25, 26). The present X-ray structural results argue against the possibility of the presence of water molecules in the interior space.

Physiological Relevance of the Present X-Ray Structural Results.

It has been reported that the fully oxidized form, immediately after complete oxidation of the fully reduced CcO, pumps protons coupled to each of the initial 2 single-electron reductions (6). In contrast, the fully oxidized as-isolated form (the slow or fast form) does not engage in proton pumping (6). Resonance Raman analyses strongly suggests that the fully oxidized form, immediately after complete oxidation of the fully reduced form, has a ferric hydroxide in the O2 reduction site (7). In contrast, the present X-ray structural results for the fully oxidized as-isolated form of CcO (the fast form) indicate the presence of a bridging peroxide structure in the O2 reduction site. This structural evidence suggests that the peroxide at the O2 reduction site suppresses the proton pumping function. The O2 reduction site is therefore tightly coupled with the proton pumping system. The O2 reduction site is not only a simple electron sink of the mitochondrial respiratory system. It also contributes to the proton pumping process.

O2 is highly hydrophobic and readily diffusible into the interior of the protein where it interacts with the metals of the O2 reduction site for production of various active oxygen species. Thus, the stable peroxide in the O2 reduction site is likely to prevent spontaneous interactions between O2 and the metal sites in the O2 reduction site, especially under the limited supply of electrons in the respiratory system.

Materials and Methods

All absorption spectral measurements and X-ray diffraction experiments were performed at 100 K, unless otherwise noted, by using the crystals of bovine heart CcO prepared as previously described (5) including crystallization as the final step. The purification method provides the fast form characterized by the Soret maximum and the cyanide binding rate (5). The method used for freezing of the crystals has been described previously (16). The absorption spectra of the crystals under X-ray irradiation without overlap of the absorption from the area of the crystals outside the X-ray beam were taken with an improved custom-designed visible absorption spectrophotometer equipped with an X-ray diffraction goniometer in BL44XU at SPring-8 (a third-generation synchrotron radiation facility in Sayo, Hyogo, Japan) as described in SI.

In the X-ray structural analyses, the anisotropic temperature factors for iron, copper, and zinc were imposed on the calculated structural factors. Other details related to the X-ray structural analyses are given in SI. Chloride content in the crystalline bovine heart CcO was examined by ICP emission spectrometric analysis using Seiko Instruments Model SPS 4000.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work is supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas 16087206 (to T.T.) and 16087208 (to S.Y.), Targeted Proteins Research Program (H.A., K.M., K.S.-I., T.O., and S.Y.), and the Global Center of Excellence Program (S.Y.) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. S.Y. is a Senior Visiting Scientist at the RIKEN Harima Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PBD ID codes 2ZXW).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0806391106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ferguson-Miller S, Babcock GT. Heme/copper terminal oxidases. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2889–2908. doi: 10.1021/cr950051s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moody AJ, Cooper CE, Rich PR. Characterisation of ‘fast’ and ‘slow’ forms of bovine heart cytochrome-c oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1059:189–207. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(05)80204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones MG, et al. A re-examination of the reactions of cyanide with cytochrome c oxidase. Biochem J. 1984;220:57–66. doi: 10.1042/bj2200057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thörnström PE, Nilsson T, Malmström BG. The possible role of the closed–open transition in proton pumping by cytochrome c oxidase: The pH dependence of cyanide inhibition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;935:103–108. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(88)90206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mochizuki M, et al. Quantitative reevaluation of the redox active sites of crystalline bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33403–33411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloch D, et al. The catalytic cycle of cytochrome c oxidase is not the sum of its two halves. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:529–533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306036101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogura T, et al. Time-resolved resonance Raman evidence for tight coupling between electron transfer and proton pumping of cytochrome c oxidase upon the change from the FeV oxidation level to the FeIV oxidation level. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:5443–5449. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moody AJ. ‘As prepared’ forms of fully oxidised haem/Cu terminal oxidases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1276:6–20. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(96)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forte E, Barone MC, Brunori M, Sarti P, Giuffrè A. Redox-linked protonation of cytochrome c oxidase: the effect of chloride bound to CuB. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13046–13052. doi: 10.1021/bi025917k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunsicker-Wang LM, Pacoma RL, Chen Y, Fee JA, Stout CD. A novel cryoprotection scheme for enhancing the diffraction of crystals of recombinant cytochrome ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Acta Crystallogr D. 2005;61:340–343. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904033906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soulimane T, et al. Structure and mechanism of the aberrant ba3-cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. EMBO J. 2000;19:1766–1776. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ostermeier C, Harrenga A, Ermler U, Michel H. Structure at 2.7 Å resolution of the Paracoccus denitrificans two-subunit cytochrome c oxidase complexed with an antibody FV fragment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10547–10553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qin L, Hiser C, Mulichak A, Garavito RM, Ferguson-Miller S. Identification of conserved lipid/detergent-binding sites in a high-resolution structure of the membrane protein cytochrome c oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16117–16122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606149103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Svensson-Ek M, et al. The X-ray crystal structures of wild-type and EQ(I-286) mutant cytochrome c oxidases from. Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Mol Biol. 2002;321:329–339. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00619-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshikawa S, et al. Redox-coupled crystal structural changes in bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. Science. 1998;280:1723–1729. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsukihara T, et al. The low-spin heme of cytochrome c oxidase as the driving element of the proton-pumping process. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15304–15309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2635097100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berglund GI, et al. The catalytic pathway of horseradish peroxidase at high resolution. Nature. 2002;417:463–468. doi: 10.1038/417463a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leslie AGW. Recent Changes to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Jnt CCP4 ESF-EAMCB Newslett Protein Crystallogr. 1992;26 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirata K, et al. Scaling of one-shot oscillation images with a reference data set. J Synchrotron Rad. 2004;11:60–63. doi: 10.1107/s0909049503024129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hersleth HP, Hsiao YW, Ryde U, Görbitz CH, Andersson KK. The crystal structure of peroxymyoglobin generated through cryoradiolytic reduction of myoglobin compound III during data collection. Biochem J. 2008;412:257–264. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unno M, Chen H, Kusama S, Shaik S, Ikeda-Saito M. Structural characterization of the fleeting ferric peroxo species in myoglobin: Experiment and theory. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13394–13395. doi: 10.1021/ja076108x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kühnel K, Derat E, Terner J, Shaik S, Schlichting I. Structure and quantum chemical characterization of chloroperoxidase compound 0, a common reaction intermediate of diverse heme enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:99–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606285103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahapatra S, et al. Structural, spectroscopic, and theoretical characterization of bis(μ-oxo)dicopper complexes, novel intermediates in copper-mediated dioxygen activation. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:11555–11574. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaila VR, Verkhovsky MI, Hummer G, Wikström M. Glutamic acid 242 is a valve in the proton pump of cytochrome c oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6255–6259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800770105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pisliakov AV, Sharma PK, Chu ZT, Haranczyk M, Warshel A. Electrostatic basis for the unidirectionality of the primary proton transfer in cytochrome c oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7726–7731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800580105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.