Abstract

Voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSC) are involved in the generation of action potentials in neurons. Brevetoxins (PbTx) are potent allosteric enhancers of VGSC function and are associated with the periodic ‘red tide’ blooms. Using PbTx-2 as a probe, we have characterized the effects of activation of VGSC on Ca2+ dynamics and extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2) signaling in neocortical neurons. Neocortical neurons exhibit synchronized spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations, which are mediated by glutamatergic signaling. PbTx-2 (100 nM) increased the amplitude and reduced the frequency of basal Ca2+ oscillations. This modulatory effect on Ca2+ oscillations produced a sustained rise in ERK1/2 activation. At 300 nM, PbTx-2 disrupted oscillatory activity leading to a sustained increase in intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) and induced a biphasic, activation followed by dephosphorylation, regulation of ERK1/2. PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation was Ca2+ dependent and was mediated by Ca2+ entry through manifold routes. PbTx-2 treatment also increased cAMP responsive element binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation and increased gene expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). These findings indicate that brevetoxins, by influencing the activation of key signaling proteins, can alter physiologic events involved in survival in neocortical neurons, as well as forms of synaptic plasticity associated with development and learning.

Keywords: brevetoxin, Ca2+ oscillations, extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2, glutamate receptors, neocortical neurons, voltage-gated sodium channel

Voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSC) are involved in the generation of action potentials in neurons. VGSC represent the molecular target for several groups of neurotoxins which alter channel function by binding to specific sites on the alpha subunit of the channel (Cestele and Catterall 2000). Brevetoxins (PbTx-1 to PbTx-10) are potent lipid-soluble polyether neurotoxins produced by the marine dinoflagellate Karenia brevis (formerly known as Gymnodinium breve and Ptychodiscus brevis), an organism linked to periodic red tide blooms in the Gulf of Mexico along the western Florida coastline (Baden 1989) and New Zealand (Ishida et al. 1995). Brevetoxins interact with site 5 of the α-subunit of the VGSC. Brevetoxins augment Na+ influx through VGSC by increasing the mean open time of the channel, inhibiting channel inactivation and shifting the activation potential to more negative values (Jeglitsch et al. 1998).

Karenia brevis blooms have been implicated in massive fish kills, bird deaths, and marine mammal mortalities (O’Shea et al. 1991:; Bossart et al. 1998). In humans, two distinct clinical entities, depending on the route of exposure, have been identified. Ingestion of bivalve mollusks contaminated with brevetoxins leads to neurotoxic shellfish poisoning, the symptoms of which include nausea, cramps, paresthesias, weakness and difficulty in movement, paralysis, seizures and coma (McFarren et al. 1965; Baden and Mende 1982; Ellis 1985). Inhalation of the aerosolized brevetoxins from sea spray results in respiratory irritation as well as dizziness, tunnel vision and skin rashes (Baden and Mende 1982; Pierce 1986). Brevetoxins are known to accumulate in the CNS at concentrations sufficient to affect CNS function when administered systemically in animals (Templeton et al. 1989; Cattet and Geraci 1993). These findings underscore the importance of studying the cellular consequences of brevetoxin exposure on the CNS.

Our laboratory has previously demonstrated that brevetoxin leads to glutamate release and acute neurotoxicity in cerebellar granule neurons (CGC) (Berman and Murray 1999). Brevetoxin induces Ca2+ influx in CGC that is responsible for this neurotoxic action (Berman and Murray 2000). Neocortical neurons in culture differ from CGC in that they exhibit spontaneous synchronous Ca2+ oscillations that are mediated by glutamatergic signaling. Oscillations in cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels are a common mode of signaling both in excitable and non-excitable cells and can increase the efficiency and specificity of gene expression (Dolmetsch et al. 1998).

Mitogen-activated protein kinases constitute a family of serine/threonine kinases, of which the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) have been shown to participate in physiologic events such as synaptic plasticity and learning and memory (Sweatt 2001). In neurons a rise in intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) mediated by NMDA receptors, Ca2+-permeable AMPA/kainate receptors and voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCC) has been shown to regulate ERK1/2 activation (Sweatt 2001). ERK1/2 phosphorylates cAMP responsive element binding protein (CREB) which governs the transcription of a number of genes including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). The ERK–CREB–BDNF cascade has been shown to be important for neuronal survival (Xia et al. 1995; Bonni et al. 1999). The regulation of ERK1/2 activation by VGSC has not been studied. In the present study, using PbTx-2 as a probe, we have characterized the effects of VGSC activation on Ca2+-dependent ERK1/2 activation and downstream signaling events.

We found that brevetoxin modulates spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations generated by neocortical neurons. PbTx-2-induced Ca2+ responses were mediated by both glutamatergic and non-glutamatergic mechanisms; the relative contributions of the two pathways varied considerably as a function of PbTx-2 concentration. The distinct Ca2+ responses induced by PbTx-2 resulted in distinct temporal pattern of ERK1/2 activation. PbTx-2 also modulated the phosphorylation of CREB and the expression of BDNF. The differential modulation of ERK1/2 depending on the extent of activation of VGSC may be explained by the activation of distinct synaptic versus extrasynaptic NMDA receptors.

Materials and methods

Neocortical neuron culture

All the animal use protocols were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Primary cultures of neocortical neurons were obtained from embryonic day 16–17 Swiss-Webster mice. Briefly, pregnant mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation and embryos were removed under sterile conditions. Neocortices were collected, stripped of meninges, minced by trituration with a Pasteur pipette and treated with trypsin for 25 min at 37°C. The cells were then dissociated by two successive trituration and sedimentation steps in soybean trypsin inhibitor and DNase containing isolation buffer, centrifuged, and resuspended in Eagle’s minimal essential medium with Earle’s salt and supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum, 10% horse serum, 100 IU/mL penicillin and 0.10 mg/mL streptomycin, pH 7.4. For [Ca2+]i, monitoring cells were plated onto poly-L-lysine coated 96-well (9 mm) clear-bottomed black-well culture plates (Corning Costar, Acton, MA, USA) at a density of 4.7 × 105 cells/cm2. For western blotting experiments cells were plated on 12-well plates. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 and 95% humidity atmosphere. Cytosine arabinoside (10 μM) was added to the culture medium on day 2 after plating to prevent proliferation of non-neuronal cells. The culture media was changed biweekly with minimal essential medium supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 5% horse serum, 100 IU/mL penicillin and 0.10 mg/mL streptomycin, pH 7.4. These cultures were used for experiments between 9 and 13 days in vitro with the exception of data depicted in Fig. 9 where 7-day in vitro cultures were used to study the developmental regulation of ERK1/2 activation.

Fig. 9.

PbTx-2-induced dephosphorylation of synaptically activated ERK1/2 is developmentally regulated. Mature (12 DIV) or immature neocortical neurons (7 DIV) were treated with 300 nM PbTx-2 and ERK1/2 activation was evaluated after the indicated times. Experiment was repeated twice with two different cultures.

Cytotoxicity assay

Conditioned medium was collected and saved, and neocortical neurons were washed three times with Locke’s buffer containing 154 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM KCl, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 2.3 mM CaCl2, 8.6 mM HEPES, 5.6 mM glucose, and 0.1 mM glycine, pH 7.4. The neurons were then exposed to PbTx-2 in 0.5 mL of Locke’s buffer for 2 h at 22°C. At the termination of PbTx-2 exposure the incubation medium was collected for later analysis of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity, and the neurons were washed twice in Locke’s buffer followed by replacement with 0.5 mL of the previously collected conditioned medium. The cell cultures were then returned to a 37°C incubator. At 24 h after PbTx-2 exposure, growth medium was collected and saved for analysis of LDH activity. LDH activity was assayed according to the method of Koh and Choi (1987).

Intracellular Ca2+ monitoring

For [Ca2+]i monitoring the cells grown in 96-well plates were first washed four times with Locke’s buffer using an automated cell washer (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland). Cells were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C with dye loading buffer (100 μL/well) containing 4 μM fluo-3 AM and 0.04% Pluronic acid in Locke’s buffer. Fluo-3 AM is taken up by cells and entrapped intracellularly after hydrolysis to fluo-3 by cell esterases. After 1 h incubation in dye loading medium, cells were washed five times with Locke’s buffer. The final volume of Locke’s buffer in each well was 100 μL or 150 μL depending on whether antagonist was added prior to PbTx-2 addition. All drug solutions were made at four times the final concentration and 50 μL were added to the culture wells.

Ca2+ monitoring was done using Fluorometric Imaging Plate Reader. Neurons were excited by the 488 nm line of the argon laser and Ca2+ bound fluo-3 emission in the 500 nm to 560 nm range was recorded with the CCD camera shutter speed set at 0.4 s. Prior to each experiment, average baseline fluorescence was set between 10 000 and 20 000 fluorescence units by adjusting the power output of the laser. Fluorescence readings were taken either once every second or once every 6 s depending on the duration of the recording.

Drug treatment

For western blotting analyses the cells grown in 12-well plates were washed three times with Locke’s buffer. The cultures were treated with the indicated drugs diluted in Locke’s buffer. After the indicated incubation period the plates were transferred to an ice slurry and the cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline to terminate the treatment. The cells were then scraped in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and centrifuged at 3500 g for 10 min to collect the cells. Lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM, EGTA, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM activated sodium orthovanadate, 1 μg/mL aprotinin, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 10 μg/mL pepstatin, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 1% NP-40) was added to the cell pellet and incubated on ice for 45 min. Thereafter the lysates were centrifuged at 25 000 g for 15 min at 4°C.

Western blotting

The supernatant were assayed by Bradford reagent to quantify protein content. Equal amounts of protein from the samples were mixed with the Laemmli sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. The protein samples were run on a 10% SDS–PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane by electroblotting. The nitrocellulose membranes were incubated in Tris-buffered saline plus Tween (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween) containing 5% skim milk powder for 1 h. After blocking, the blots were incubated overnight in primary antibody diluted in Tris-buffered saline plus Tween containing 5% bovine serum albumin. The blots were washed with Tris-buffered saline plus Tween and incubated with the secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase for 1 h, washed with Tris-buffered saline plus Tween and exposed to ECL plus for 3 min. Blots were exposed to Kodak hyperfilm and developed. Bands were analyzed using a Multimager (Alpha Innotech Corporation, San Leandro, CA, USA).

RT-PCR

The neocortical neurons were treated for 4 h with the indicated treatments. The cells were then washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and then lysed with TRI reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was used to analyze the expression of mRNA for BDNF and β-actin (internal control). The sense and antisense primers used were 5′-GCGGCAGATAAAAAGACTGC-3′ and 5′-CTTATGAATCGC-CAGCCAAT-3′ for BDNF and 5′-ATGGATGACGATATCGCT-3′ and 5′-ATGAGGTAGTCTGTCAGGT-3′ for β-actin. The thermal cycles consisted of denaturation at 94°C for 15 s, annealing at 54°C for 15 s and extension at 72°C for 30 s followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The numbers of cycles optimized within the linear range of amplification for each primer set were 28 cycles BDNF and 25 cycles for β-actin. The amplification products were fractionated on 2% agarose gel and documented using a Kodak DC290 digital camera. The resulting images were digitized and quantified using UN-SCAN-IT software (Silk Scientific Inc., Orem, UT, USA) normalized to that of β-actin.

Data analysis

Non-linear regression analysis, frequency and amplitude analysis, ANOVA and other curve fitting were done using GraphPad (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Materials

Trypsin, penicillin, streptomycin, heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, horse serum and soybean trypsin inhibitor were obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Norcross, GA, USA). Minimum essential medium, Deoxyribonuclease (DNAse), poly-L-lysine, cytosine arabinosoide, (+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclo-hepten-5,10-imine maleate (MK-801), 2,3-dioxo-6-nitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzo[f]quinoxaline-7-sulfonamide (NBQX), cyclothiazide, and NMDA, were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). (S)-4-Carboxyphenylglycine (S-4-CPG) was from Tocris (Ballwin, MO, USA). Nifedipine was obtained from RBI (Natick, MA, USA). Pluronic acid and fluo-3 AM were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). Phospho-ERK1/2 and total-ERK1/2 antibody were obtained from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA, USA), and phospho-CREB antibody from Upstate Biotechnology (Charlottesville, VA, USA). ECL plus kit was from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Materials for RT-PCR were obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). 2-[2-[4-(4-Nitrobenzyloxy)phenyl]ethyl] isothiourea methanesulfonate (KB-R7943) was a generous gift of Dr T. Watano (Kanebo, Osaka, Japan).

Results

PbTx-2 modulates Ca2+ oscillations in neocortical neurons

Neocortical neurons exhibit spontaneous oscillations in intracellular [Ca2+]i. These Ca2+ oscillations are action potential dependent and are tetrodotoxin-sensitive. These oscillations are triggered by the activation of AMPA receptors and involve secondary recruitment of NMDA and metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) stimulation. We therefore investigated the effect of PbTx-2 on these spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations. At low concentrations (10–100 nM), PbTx-2 significantly increased the amplitude and duration of a single Ca2+ spike (Figs 1 and 2a). The increase in amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations was accompanied by a decrease in the frequency (Fig. 2b), and therefore the integrated Ca2+ influx, quantified as the area under the curve, remained unaltered (Fig. 2c). PbTx-2 at concentrations greater than 100 nM disrupted Ca2+ oscillations and produced a sustained rise in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 1). The sustained rise in Ca2+ after exposure to 300 nM PbTx-2 returned to an oscillatory state after a period of 25–30 min, whereas cultures treated with 1 μM PbTx-2 did not exhibit Ca2+ oscillations, even after a period of 30 min (data not shown). Thus, depending on the concentration, PbTx-2 can differentially affect Ca2+ dynamics in neocortical neurons which may in turn lead to distinct downstream signaling effects.

Fig. 1.

The effect of PbTx-2 on Ca2+ dynamics in neocortical neurons. Ca2+ imaging in mature neocortical neurons exhibiting spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations treated with PbTx-2. These data are from a representative experiment performed in sextuplicate.

Fig. 2.

Concentration-dependent effect of PbTx-2 on peak height (amplitude), oscillation frequency and area under the curve (AUC) of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in neurocortical neurons. Each point represents mean ± SEM of triplicate values.

PbTx-2-induced modulation of intracellular Ca2+ dynamics mediated by both glutamatergic and non-glutamatergic mechanisms

In CGC the brevetoxin-induced Ca2+ response is derived from Ca2+ influx through NMDA receptors, L-type Ca2+ channels and reversal of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (Berman and Murray 2000). It was therefore of interest to determine whether the PbTx-2-induced increment in Ca2+ response in neocortical neurons involved the same pathways. We first characterized the Ca2+ response induced by 100 nM PbTx-2 which leads to an increase in amplitude and reduction in the frequency of basal spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations. The NMDA antagonist MK-801 (1 μM) reduced 100 nM PbTx-2-induced Ca2+ spike amplitude by 70% (Figs 3 and 4b). Although MK-801 alone does affect the amplitude of basal Ca2+ oscillations, these results show that the incremental response to PbTx-2 was also largely dependent on the activation of NMDA receptors. The basal spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations were not affected by an inhibitor of L-type Ca2+ channels, nifedipine (1 μM), or by an inhibitor of the reverse mode of operation of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, KB-R7943 (1 μM) (data not shown). Nifedipine and KB-R7943, however, significantly reversed the decrease in frequency of Ca2+ oscillations produced by 100 nM PbTx-2 (Figs 3 and 4a). Nifedipine also significantly decreased the amplitude of 100 nM PbTx-2-mediated Ca2+ oscillations, whereas KB-R7943 did not affect the amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations (Fig. 4b). A hallmark of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillation in neocortical neurons is the control of their frequency by the AMPA receptors (Dravid & Murray, submitted). The AMPA receptor antagonist, NBQX (1 μM), decreased the frequency of basal Ca2+ oscillation and produced a similar effect on Ca2+ oscillations occurring in the presence of 100 nM PbTx-2 (Fig. 4a) indicating that these oscillations produced by PbTx-2 retain the properties of synaptically mediated Ca2+ oscillations.

Fig. 3.

Pharmacological evaluation of 100 nM PbTx-2-induced Ca2+ oscillations in neocortical neurons. All antagonists were used at 1 μM concentration except CPG which was used at a concentration of 500 μM. Data shown are from a representative experiment performed in quadruplicate.

Fig. 4.

Oscillation frequency and maximum amplitude analysis of the results derived from Ca2+ oscillation measurements occurring in the presence of 100 nM PbTx-2. In all cases the initial Ca2+ spike produced by PbTx-2 was excluded from data analysis. In (a), *p < 0.05 compared to PbTx-2. In (b), ***p < 0.001 and *p < 0.05 compared to PbTx-2.

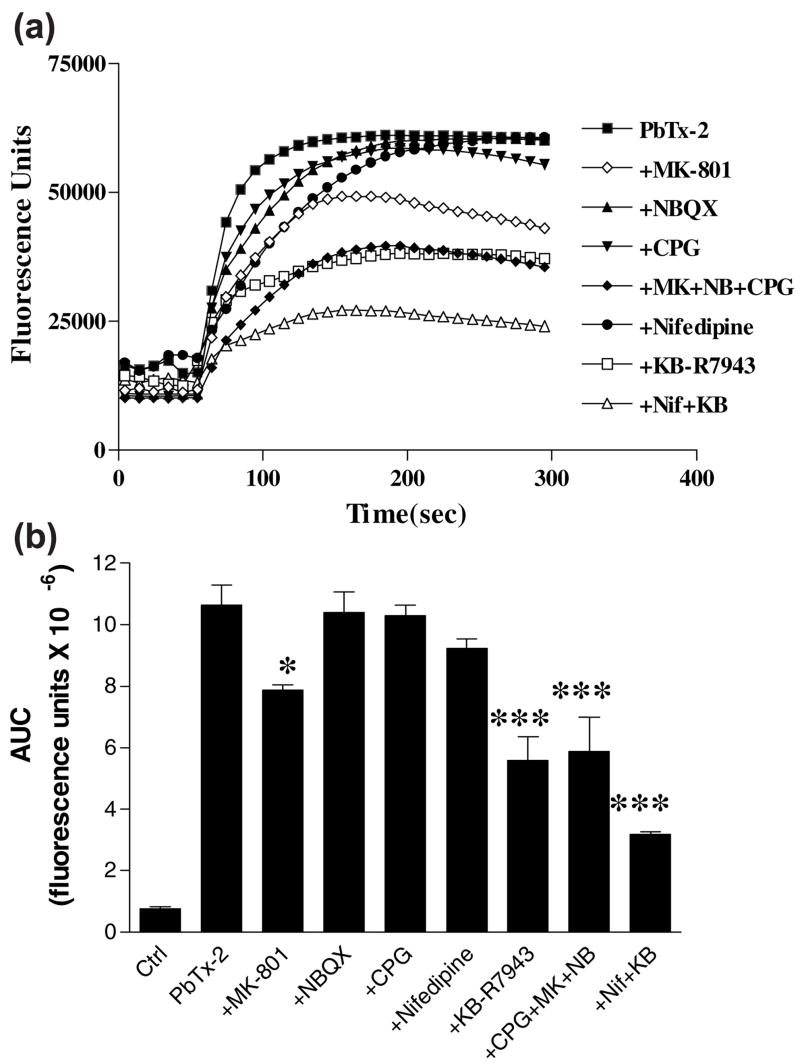

We further investigated the routes of Ca2+ entry that underlie the sustained rise in intracellular [Ca2+]i after exposure to 1 μM of PbTx-2. The NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801 (1 μM), produced a significant reduction in the area under the curve after PbTx-2 treatment (Fig. 5). S-4-CPG (500 μM), the mGluR antagonist, and NBQX (1 μM), the AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist, alone did not significantly reduce the Ca2+ influx, but together produced an additive reduction with MK-801 (Figs 5a and b). KB-R7943 (1 μM) was most effective in reducing Ca2+ influx, whereas nifedipine (1 μM) alone did not significantly reduce Ca2+ influx but was efficacious in combination with KB-R7943. Thus reversal of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger is the most important routes of Ca2+ entry followed by NMDA receptors after PbTx-2 exposure (1 μM) (Fig. 5). Thus the major routes of Ca2+ entry after PbTx-2 exposure in neocortical neurons are similar to those earlier reported in CGC (Berman and Murray 2000).

Fig. 5.

Pharmacological evaluation of 1 μM PbTx-2-induced Ca2+ in-flux in neocortical neurons. All antagonists were used at 1 μM concentration except CPG which was used at 500 μM concentration. (a) Raw, time–response data with each point representng mean of triplicates. (b) Area under the curve (AUC) analysis. Each value is mean ± SEM of triplicates. ***p < 0.001 compared to PbTx-2 and *p < 0.05 compared to PbTx-2.

PbTx-2 does not produce acute neurotoxicity in neocortical neurons

In CGC the brevetoxin, PbTx-2 produces acute toxicity with an EC50 of 80.5 ± 5.9 nM that was prevented by the application of NMDA receptor antagonists (Berman and Murray 1999). In contrast PbTx-2 did not produce acute toxicity in neocortical neurons as demonstrated by both the absence of LDH release after 2 h of incubation with PbTx-2 as well as the normal appearance of neurons on microscopic examination. Only a 3 μM concentration of PbTx-2 produced toxicity after 24-h exposure (Table 1). Neocortical neurons thus appear to be much less vulnerable than CGC to acute PbTx-2-induced toxicity.

Table 1.

PbTx-2 does not produce acute neurotoxicity in neocortical neurons

| Treatment | 2 h (LDH units/well) | 24 h (LDH units/well) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 12 ± 2 | 130 ± 10 |

| PbTx-2 (1 μM) | 13 ± 1 | 135 ± 12 |

| PbTx-2 (3 μM) | 24 ± 2 | 350 ± 24 |

| Cell lysis | 872 ± 42 | 1197 ± 63 |

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) efflux measurements were performed at 2 h and 24 h after treatment with PbTx-2. Each value represents mean ± SEM of triplicate values. The experiment was repeated three times on different cultures with similar results.

PbTx-2 exposure leads to an increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation

Increase in intracellular Ca2+ through NMDA receptors, L-type calcium channel, Ca2+ permeable AMPA/kainate receptors and release of intracellular stores of Ca2+ after mGluR activation have all been shown to induce activation of ERK1/2 (Sweatt 2001). The synaptic activity exhibited by the neocortical neurons is responsible for basal ERK1/2 activation. Blocking the synaptic activity by tetrodotoxin, a VGSC antagonist, leads to a decrease in ERK1/2 activation as indicated by a decrease in the dually phosphorylated (p-ERK1/2) form of the ERK1/2 (Fig. 6). This synaptic activity-induced ERK1/2 activation is mediated by Ca2+ influx through NMDA receptors since 100 nM MK-801 reduces the synaptic activity-induced ERK1/2 activation to a level equivalent to that observed with tetrodotoxin treatment (Fig. 6). Blocking AMPA/kainate receptors with NBQX did not inhibit basal ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 6). NBQX reduces the frequency of Ca2+ spikes but does not completely eliminate Ca2+ oscillations and these NBQX-insensitive Ca2+ spikes may be sufficient for basal ERK1/2 activation. Inasmuch as PbTx-2 exposure alters Ca2+ dynamics in neocortical neurons and since Ca2+ has been shown to be a key regulator of ERK1/2 activation, we explored the effects of PbTx-2 on ERK1/2 activation. We first examined the temporal pattern of ERK1/2 activation by two different concentrations of PbTx-2 which differ in their effect on Ca2+ oscillations exhibited by neocortical neurons. PbTx-2 at 100 nM, a concentration that alters the amplitude and frequency of the Ca2+ oscillations but does not disrupt the oscillatory state, produced a steep rise (twofold over control) in ERK1/2 activation within 15 min (Figs 7a and c). This ERK1/2 activation was sustained for the entire 2 h observation period. On the other hand, 300 nM PbTx-2, a concentration that disrupts the oscillations and produces sustained rise in cytosolic Ca2+, produced a steep rise (threefold over control) in ERK1/2 activation within 15 min followed by a decrease in the phosphorylation state, that was reduced below the basal level after 1 h of treatment (Figs 7b and c). Though both concentrations of PbTx-2 produced an increase in p-ERK1/2, the temporal patterns of ERK1/2 activation were distinct. No changes in the total ERK1/2 levels were observed by either PbTx-2 treatment (Fig. 7). We further examined the concentration dependence of PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation at the 15 min time point, inasmuch as ERK1/2 phosphorylation was near maximal at 15 min after exposure to both concentrations of PbTx-2. PbTx-2 produced a concentration-dependent increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 8a). The EC50 obtained from non-linear regression analysis of the PbTx-2 concentration–response curve was 96.8 nM (Fig. 8b).

Fig. 6.

Basal synaptic activity produced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in neocortical neurons. Inhibition by VGSC antagonist, 1μM tetrodotoxin (TTX), NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801 (100 nM), and lack of effect of AMPA receptor antagonist, NBQX (1 μM) are depicted. The neocortical neurons were treated with the antagonist for 1 h and thereafter the total protein was collected and evaluated for phosphorylated form and total ERK1/2. The experiment was repeated twice with two different cultures. ***p < 0.001 and **p < 0.01 compared to control.

Fig. 7.

Temporal pattern of PbTx-2 and NMDA (10 μM)-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in neocortical neurons. Neocortical neurons treated with (a) 100 nM PbTx-2 or (b) 300 nM PbTx-2 for the indicated times. (c) Quantitative analysis of the relative band intensities. Each point represents mean ± SEM of triplicate values.

Fig. 8.

Concentration-dependent activation of ERK1/2 by PbTx-2. Neocortical neurons were treated for 15 min with different concentrations of PbTx-2. Experiment was repeated three times. Each point in the non-linear regression curve represents the mean ± SEM.

In hippocampal neurons in culture, CREB dephosphorylation is developmentally regulated (Sala et al. 2000; Hardingham and Bading 2002). Similarly, the influence of 300 nM PbTx-2 on ERK1/2 activation was altered as a function of development. In contrast to the response in 12 DIV cultures, 300 nM PbTx-2 stimulated ERK1/2 activation in a more sustained pattern in 7 DIV cultures (Fig. 9). These distinct temporal patterns of PbTx-2 activation are most likely related to developmental regulation of phosphatases involved in the inactivation of ERK1/2.

PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation is mediated by manifold routes of Ca2+ influx

To determine whether the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was mediated by a rise in intracellular Ca2+ and not Na+, we performed a concentration response study for PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation in the presence and absence of extracellular Ca2+. Removal of extracellular Ca2+ led to a decrease in the basal phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Fig. 10), indicating that the ERK1/2 activation associated with synaptic activity is mediated by Ca2+ entry through NMDA receptors. PbTx-2 did not induce ERK1/2 activation in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 10), suggesting that the extracellular compartment is the source of Ca2+ responsible for ERK1/2 activation. PbTx-2-induced Ca2+ influx occurs through various routes; therefore, we investigated the relative contributions of these Ca2+ entry pathways. After a 15 min pre-treatment with different antagonists, 1 μM PbTx-2 was added to neocortical neurons. Treatment was terminated after 15 min of PbTx-2 exposure and cell extracts were analyzed for ERK1/2 activation. We found that, similar to the results obtained with Ca2+ imaging, the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger inhibition by KB-R7943 was most efficacious in inhibiting PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 11). Pre-treatment with MK-801, nifedipine and S-4-CPG also led to significant reductions in the PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation. It should be noted that MK-801 is more effective in reducing PbTx-2-induced Ca2+ influx than either nifedipine or S-4-CPG (Fig. 5); however, the reduction in PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation by nifedipine and S-4-CPG is comparable to that produced by MK-801 (Fig. 11). In addition to Ca2+ load, therefore, the route of Ca2+ entry may also dictate the degree of ERK1/2 activation.

Fig. 10.

Extracellular Ca2+ dependence of PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation. Neocortical neurons were treated with the indicated concentration of PbTx-2 for 15 min in the presence (+ Ca2+) or absence (− Ca2+) of extracellular Ca2+. The experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

Fig. 11.

Pharmacological characterization of PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation. The neocortical neurons were treated with 1μM PbTx-2 after 15 min pre-treatment with the different antagonists. PbTx-2 exposure was for 15 min, following which total protein was extracted and processed for western blotting. All antagonists were used at a concentration of 1 μM except CPG which was used at 500 μM concentration. ***p < 0.001 and *p < 0.05 compared to PbTx-2.

Role of MEK, Ca2+–calmodulin kinase II and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation

ERK1/2 activation is exclusively regulated by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 (MEK1/2), the immediate upstream dual-specificity kinases that phosphorylate ERK1/2. Treatment of neurons with PD98059 (50 μM), a specific blocker of MEK1/2 (Alessi et al. 1995), inhibited both the basal and 300 nM PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 12). Ca2+–calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII) has been suggested to be a key mediator of glutamate-induced ERK1/2 activation (Vanhoutte et al. 1999). Treatment of neocortical neurons with the specific CaMKII inhibitor KN-93 (40 μM) significantly reduced the PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 12). Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) has also been shown to contribute to both NMDA and glutamate-induced ERK1/2 activation (Walker et al. 2000; Perkinton et al. 2002). We therefore evaluated the role that PI3K played in the activation of PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation. Wortmannin (100 nM), a selective inhibitor of PI3K, lead to a partial reduction in the PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 12). These data indicate that other than the classical Ras-Raf-1 kinase/MEK1 pathway (Rosen et al. 1994), both the CaMKII and PI3K pathway may contribute to the observed activation of ERK1/2 by PbTx-2.

Fig. 12.

The effect of CaMKII, MEK and PI3K inhibitors on PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation. The neocortical neurons were treated with 1 μM PbTx-2 after a 15 min pre-incubation with the inhibitors. All the inhibitors significantly reduce PbTx-induced ERK1/2 activation. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05 compared to PbTx-2.

PbTx-2 augments CREB phosphorylation and BDNF expression

To examine whether PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation is accompanied by the activation of a downstream transcription factor and alteration in gene expression, we studied the phosphorylation of CREB by immunoblotting and BDNF expression by RT-PCR. CREB is activated by phosphorylation at Ser 133. Treatment with 300 nM PbTx-2 lead to an increase in CREB phosphorylation which peaked at 30 min (Fig. 13). PbTx-2 also induced an increase in BDNF gene expression after 4 h of treatment (Fig. 14). These studies indicate that the effect of PbTx-2 is not restricted to phosphorylation of signaling proteins, but also affects neuronal gene expression.

Fig. 13.

The effect of NMDA and PbTx-2 on CREB phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of CREB was assessed using a phospho-CREB specific antibody that detects CREB phosphorylated at Ser 133 site. NMDA and PbTx-2 produce distinct temporal pattern of CREB activation. A representative blot is shown. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

Fig. 14.

PbTx-2 increases BDNF expression in neocortical neurons. The neocortical neurons were exposed for 4 h with the indicated treatments and RNA was extracted. BDNF and β-actin (internal control) expression levels were detected by RT-PCR.

Discussion

We have used PbTx-2 as a probe to identify the effects of activation of VGSC on Ca2+ dynamics and ERK1/2 activation in neocortical neurons. We have previously shown that PbTx-2 induces acute neurotoxicity in CGC which is mediated by glutamate release (Berman and Murray 1999). The neocortical neurons were resistant to PbTx-2-induced acute neurotoxicity. There are several possible reasons for these differences in cell specific susceptibility. The CGC are predominantly glutamatergic neurons, whereas cultures of neocortical neurons also have a considerable number of GABAergic interneurons which have a tonic inhibitory control on the network (Schousboe et al. 1985). In addition, the spontaneous synaptic neuronal activity in neocortical neurons may lead to tonic activation of cell survival elements (Hardingham et al. 2002) that may counteract the cell death signaling enhanced by PbTx-2 treatment.

The Ca2+ oscillations occurring in the presence of 100 nM PbTx-2 shared many of the same properties as synaptically mediated spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations, in that the frequency was AMPA receptor dependent. Although PbTx-2-induced Ca2+ oscillations were mostly dependent on the activation of NMDA receptors, L-type Ca2+ channels and the reverse mode of operation of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger also participated in these oscillations. Blockade of either L-type Ca2+ channels or Na+/Ca2+ exchanger altered the frequency of these oscillations. At concentrations greater than or equal to 300 nM, PbTx-2 disrupted Ca2+ oscillations, leading to a sustained rise in intracellular Ca2+, suggesting that at these elevated concentrations PbTx-2 modulation of Ca2+ dynamics may not be restricted to synaptic augmentation but rather more generalized to include both synaptic and extrasynaptic receptor activation. The Ca2+ entry induced by 300 nM PbTx-2 did not have an AMPA receptor component, which may be explained by the depolarizing effect of PbTx-2 alone thereby eliminating the requirement for AMPA receptor activation to remove Mg2+ block of NMDA receptor. Increases in intracellular Na+ by PbTx-2 results in the reversal of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, which is the major source of Ca2+ entry mediated by 300 nM PbTx-2.

Brevetoxin stimulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation was dependent on Ca2+ influx. The different Ca2+ responses induced by the 100 nM and 300 nM concentrations of PbTx-2 had distinct temporal patterns of downstream ERK1/2 activation. The ERK1/2 activation produced by 300 nM PbTx-2 followed a biphasic response and led to an apparent dephosphorylation of ERK1/2 relative to basal levels. The lower concentration of PbTx-2, which augmented the amplitude of synaptic Ca2+ oscillations, induced a sustained activation of ERK1/2. NMDA receptor-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation is transient and regulated by striatal enriched phosphatases (Paul et al. 2003). Conversely, activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCC) leads to a sustained activation of ERK1/2 (Paul et al. 2003). Our unpublished observations indicate that the Ca2+ response mediated by 55 mM KCl, which activates the VGCC, and 300 nM PbTx-2 are similar in magnitude, suggesting that the time course of ERK1/2 activation may depend on the source of Ca2+ entry and not on the Ca2+ load per se. Striatal enriched phosphatase has been shown to be associated with the NMDA receptor protein scaffold complex and is responsible for the source specificity of ERK1/2 dephosphorylation in striatal neurons (Pelkey et al. 2002; Paul et al. 2003).

The neuronal localization of NMDA receptors dictates their influence on cellular responses. For instance, activation of synaptic NMDA receptors leads to sustained enhancement of AMPA responses, whereas extrasynaptic NMDA receptors lead to lasting depression of AMPA receptor responses (Lu et al. 2001). CREB phosphorylation has been shown to be positively regulated by Ca2+ entry through synaptic NMDA receptors, whereas extrasynaptic NMDA receptors lead to the inactivation of synaptically mediated CREB phosphorylation (Hardingham et al. 2002). A similar mechanism may be invoked to account for the distinct temporal patterns of ERK1/2 activation produced by the two concentrations of PbTx-2 in neocortical neurons. An increase in Ca2+ influx through the synaptic NMDA receptors and through L-type Ca2+ channels triggered by 100 nM PbTx-2 produced a sustained activation of ERK1/2. On the other hand, 300 nM PbTx-2 may lead to a more generalized depolarization and higher levels of glutamate release. This excess glutamate could spillover to activate extrasynaptic NMDA receptors, leading to activation of a shut-off mechanism and therefore a shorter duration of ERK1/2 activation. In hippocampal neurons ERK1/2 activation does not seem to be regulated differentially by synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors since bath application of NMDA does not shut-off the synaptically mediated ERK1/2 activation (Sala et al. 2000). In neocortical neurons bath application of NMDA has been found to dephosphorylate basal p-ERK1/2 (Chandler et al. 2001). We have found similar results in our neocortical culture model using NMDA. The apparent differences in hippocampal and neocortical neurons may arise from differences in the post-synaptic density proteins linked to NMDA receptors. These observations indicate that not only receptor specificity, but also receptor localization may dictate the temporal pattern of ERK1/2 activation.

Higher concentrations of PbTx-2 lead to a robust increase in ERK1/2 activation which is mediated by multiple routes of Ca2+ entry. In neocortical and striatal neurons NMDA-induced ERK1/2 activation is completely dependent on PI3K activity (Chandler et al. 2001; Perkinton et al. 2002). ERK1/2 activation by 1 μM PbTx-2 treatment was not completely abolished by treatment with wortmannin, indicating that NMDA receptors may not be solely responsible for ERK1/2 activation following exposure to PbTx-2. This accords with the fact that inhibition of Ca2+ entry through other routes, including L-type channels, reversal of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and mGluR also reduced the ERK1/2 activation produced by this high concentration of PbTx-2. Protein kinase A and the Ca2+-dependent protein kinase C have been shown to be upstream regulators of ERK1/2 in dorsal horn neurons (Hu and Gereau 2003), and may therefore also contribute to PbTx-2-induced ERK1/2 activation.

The duration of ERK1/2 activation may modify the attendant cellular responses. In PC12 cells transient ERK1/2 activation leads to cell proliferation, whereas sustained activation leads to differentiation (Traverse et al. 1992). The role of sustained versus transient ERK1/2 activation in post-mitotic neurons is not known. Synaptic transmission and NMDA receptor activation is necessary for cell survival in the developing brain (Ikonomidou et al. 1999). In addition, stimulation of synaptic activity by environmental enrichment inhibits spontaneous apoptosis in hippocampus and is therefore neuroprotective (Young et al. 1999). NMDA receptor mediated synaptic activity has been shown to be anti-apoptotic and this is associated with activation of the CREB–BDNF cascade (Hardingham et al. 2002). Since ERK1/2 activation is accompanied by CREB and BDNF activation, the synaptically mediated sustained ERK1/2 activation may serve as a pro-survival signal. Further studies will be needed to directly demonstrate whether synaptic activity enhancing concentrations of VGSC activators are anti-apoptotic.

VGSC are vital for normal CNS functioning and abnormal gating of these ion channels may lead to pathophysiological conditions exhibited as epileptiform diseases (Kohling 2002). VGSC are also molecular targets for numerous neurotoxins (Cestele and Catterall 2000). The results from the present study characterize the initial molecular signaling events triggered by exposure to a VGSC activating neurotoxin, and may have implications for neurological diseases such as epilepsy. As mentioned previously, ERK1/2 have been shown to regulate important physiological functions such as learning, memory, growth and survival in neurons (Grewal et al. 1999; Sweatt 2001). The results of the present study indicate that the cellular effects of brevetoxin may not always be manifested by neurotoxic sequelae (Berman and Murray 1999) but by modulating key signaling pathways in the CNS may also lead to positive influences on neuronal plasticity and survival.

Abbreviations

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular Ca2+ CaMKII, Ca2+–calmodulin kinase II

- CGC

cerebellar granule cells

- CREB

cAMP responsive element binding protein

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2

- KB-R7943

2-[2-[4-(4-ni-trobenzyloxy)phenyl]ethyl] isothiourea methanesulfonate

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- mGluR

metabotropic glutamate receptor

- MEK1/2

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2

- MK-801

(+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5,10-imine maleate

- NBQX

2,3-dioxo-6-nitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzo[f]quinoxaline-7-sulfonamide

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PbTx-2

brevetoxin-2

- S-4-CPG

(S)-4-carboxyphenylglycine

- VGCC

voltage-gated calcium channel

- VGSC

voltage-gated sodium channel

References

- Alessi DR, Cuenda A, Cohen P, Dudley DT, Saltiel AR. PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27489–27494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baden DG. Brevetoxins: unique polyether dinoflagellate toxins. FASEB J. 1989;3:1807–1817. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.7.2565840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baden DG, Mende TJ. Toxicity of two toxins from the Florida red tide marine dinoflagellate, Ptychodiscus brevis. Toxicon. 1982;20:457–461. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(82)90009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman FW, Murray TF. Brevetoxins cause acute excitotoxicity in primary cultures of rat cerebellar granule neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman FW, Murray TF. Brevetoxin-induced autocrine excitotoxicity is associated with manifold routes of Ca2+ influx. J Neurochem. 2000;74:1443–1451. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonni A, Brunet A, West AE, Datta SR, Takasu MA, Greenberg ME. Cell survival promoted by the Ras-MAPK signaling pathway by transcription-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Science. 1999;286:1358–1362. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossart GD, Baden DG, Ewing RY, Roberts B, Wright SD. Brevetoxicosis in manatees (Trichechus manatus latirostris) from the 1996 epizootic: gross, histologic, and immunohistochemical features. Toxicol Pathol. 1998;26:276–282. doi: 10.1177/019262339802600214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattet M, Geraci JR. Distribution and elimination of ingested brevetoxin (PbTx-3) in rats. Toxicon. 1993;31:1483–1486. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(93)90214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cestele S, Catterall WA. Molecular mechanisms of neurotoxin action on voltage-gated sodium channels. Biochimie. 2000;82:883–892. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)01174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler LJ, Sutton G, Dorairaj NR, Norwood D. N-Methyl D-aspartate receptor-mediated bidirectional control of extracellular signal-regulated kinase activity in cortical neuronal cultures. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2627–2636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch RE, Xu K, Lewis RS. Calcium oscillations increase the efficiency and specificity of gene expression. Nature. 1998;392:933–936. doi: 10.1038/31960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis S. Brevetoxins: chemistry and pharmacology of ‘red tide’ toxins from Ptychodiscus brevis (formerly Gymnodinium breve) Toxicon. 1985;23:469–472. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(85)90030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal SS, York RD, Stork PJ. Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase signalling in neurons. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:544–553. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(99)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham GE, Bading H. Coupling of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors to a CREB shut-off pathway is developmentally regulated. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1600:148–153. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(02)00455-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham GE, Fukunaga Y, Bading H. Extrasynaptic NMDARs oppose synaptic NMDARs by triggering CREB shut-off and cell death pathways. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:405–414. doi: 10.1038/nn835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu HJ, Gereau RW., 4th ERK Integrates PKA and PKC signaling in superficial dorsal horn neurons. II Modulation of neuronal excitability. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:1680–1688. doi: 10.1152/jn.00341.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidou C, Bosch F, Miksa M, Bittigau P, Vockler J, Dikranian K, Tenkova TI, Stefovska V, Turski L, Olney JW. Blockade of NMDA receptors and apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Science. 1999;283:70–74. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida H, Nozawa A, Totoribe K, et al. Brevetoxin B1, a new polyether marine toxin from the New Zealand shellfish, Austrovenus stutchburyi. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:725–728. [Google Scholar]

- Jeglitsch G, Rein K, Baden DG, Adams DJ. Brevetoxin-3 (PbTx-3) and its derivatives modulate single tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium channels in rat sensory neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:516–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh JY, Choi DW. Quantitative determination of glutamate mediated cortical neuronal injury in cell culture by lactate dehydrogenase efflux assay. J Neurosci Meth. 1987;20:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(87)90041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohling R. Voltage-gated sodium channels in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2002;43:1278–1295. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.40501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Man H, Ju W, Trimble WS, MacDonald JF, Wang YT. Activation of synaptic NMDA receptors induces membrane insertion of new AMPA receptors and LTP in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2001;29:243–254. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarren EF, Silva FJ, Tanabe H, Wilson WB, Campbell JE, Lewis KH. The occurrence of a ciguatera-like poison in oysters, clams, and Gymnodinium breve cultures. Toxicon. 1965;3:111–123. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(65)90005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea TJ, Rathbun GB, Buergelt CD, Odell DK. An epizootic of Florida manatees associated with a dinoflagellate bloom. Mar Mamm Sci. 1991;7:165–179. [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Nairn AC, Wang P, Lombroso PJ. NMDA-mediated activation of the tyrosine phosphatase STEP regulates the duration of ERK signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:34–42. doi: 10.1038/nn989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkey KA, Askalan R, Paul S, Kalia LV, Nguyen TH, Pitcher GM, Salter MW, Lombroso PJ. Tyrosine phosphatase STEP is a tonic brake on induction of long-term potentiation. Neuron. 2002;34:127–138. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00633-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkinton MS, Ip JK, Wood GL, Crossthwaite AJ, Williams RJ. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is a central mediator of NMDA receptor signalling to MAP kinase (Erk1/2), Akt/PKB and CREB in striatal neurones. J Neurochem. 2002;80:239–254. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RH. Red tide (Ptychodiscus brevis) toxin aerosols: a review. Toxicon. 1986;24:955–965. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(86)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen LB, Ginty DD, Weber MJ, Greenberg ME. Membrane depolarization and calcium influx stimulate MEK and MAP kinase via activation of Ras. Neuron. 1994;12:1207–1221. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90438-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala C, Rudolph-Correia S, Sheng M. Developmentally regulated NMDA receptor-dependent dephosphorylation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3529–3536. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03529.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schousboe A, Drejer J, Hansen GH, Meier E. Cultured neurons as model systems for biochemical and pharmacological studies on receptors for neurotransmitter amino acids. Dev Neurosci. 1985;7:252–262. doi: 10.1159/000112294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweatt JD. The neuronal MAP kinase cascade: a biochemical signal integration system subserving synaptic plasticity and memory. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Templeton CB, Poli MA, Solow R. Prophylactic and therapeutic use of an anti-brevetoxin (PbTx-2) antibody in conscious rats. Toxicon. 1989;27:1389–1395. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(89)90070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traverse S, Gomez N, Paterson H, Marshall C, Cohen P. Sustained activation of the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascade may be required for differentiation of PC12 cells. Comparison of the effects of nerve growth factor and epidermal growth factor. Biochem J. 1992;288:351–355. doi: 10.1042/bj2880351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoutte P, Barnier JV, Guibert B, Pages C, Besson MJ, Hipskind RA, Caboche J. Glutamate induces phosphorylation of Elk-1 and CREB, along with c-fos activation, via an extracellular signal-regulated kinase-dependent pathway in brain slices. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:136–146. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EH, Pacold ME, Perisic O, Stephens L, Hawkins PT, Wymann MP, Williams RL. Structural determinants of phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibition by wortmannin, LY294002, quercetin, myricetin, and staurosporine. Mol Cell. 2000;6:909–919. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(05)00089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis RJ, Greenberg ME. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;270:1326–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young D, Lawlor PA, Leone P, Dragunow M, During MJ. Environmental enrichment inhibits spontaneous apoptosis, prevents seizures and is neuroprotective. Nat Med. 1999;5:448–453. doi: 10.1038/7449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]