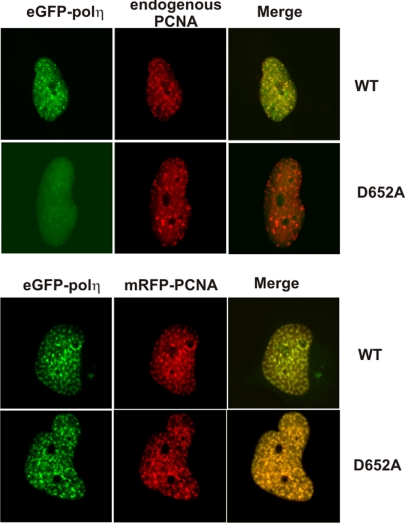

Acharya et al. (1) recently examined the role of different motifs in human DNA polymerase (pol)η. Their data suggested that mutations in the ubiquitin-binding (UBZ) motif of polη had no effect on its localization into replication foci. However, the first 4 authors of this Letter have independently found, in many experiments, that mutations D652A, C638A, and H654A in the UBZ motif all greatly reduced the accumulation of polη in replication foci (refs. 2 and 3 and our unpublished data). Acharya et al. (1) used cells cotransfected with GFP-PCNA and FLAGpolη, whereas we analyzed the localization of eGFPpolη with endogenous PCNA. Fig. 1 demonstrates unequivocally that this is the cause of the discrepancy. Transfection of eGFPpolη–D652A alone failed to form foci, as reported previously (2). In contrast, when cotransfected with mRFP-PCNA, eGFPpolη–D652A did form foci, as shown by Acharya et al. (1). We conclude that the UBZ motif of polη is required for correct localization of polη when cellular concentrations of PCNA are unperturbed. If, however, the concentration of PCNA is artificially increased, the UBZ of polη becomes dispensable. Neither our data nor those of Acharya et al. (1) provide evidence that the ubiquitinated species to which the UBZ motif binds in the nuclear foci is ubiquitinated PCNA. In fact, we have recently shown that ubiquitination of PCNA appears not to be required for polη accumulation into foci, but it does increase the residence time within foci, suggesting the existence of multiple signals that are required for controlling the dynamics of UBZ-containing proteins in the nucleus (4). Wrnip1 provides a further example in which mutations in the UBZ motif abolished localization into foci (5).

Fig. 1.

MRC5 cells were transfected with either wild-type or D652A mutant eGFPpolη without (Uppers) or with (Lowers) mRFP-PCNA. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were UV-irradiated (30 Jm−2) and incubated for 6 h. Cells were fixed in paraformaldehyde and examined directly for epifluorescence or incubated with methanol in those samples which were analyzed for endogenous PCNA by immunofluorescence.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Acharya N, et al. Roles of PCNA-binding and ubiquitin-binding domains in human DNA polymerase eta in translesion DNA synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17724–17729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809844105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bienko M, et al. Ubiquitin-binding domains in translesion synthesis polymerases. Science. 2005;310:1821–1824. doi: 10.1126/science.1120615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plosky BS, et al. Controlling the subcellular localization of DNA polymerases iota and eta via interactions with ubiquitin. Embo J. 2006;25:2847–2855. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabbioneda S, et al. Effect of proliferating cell nuclear antigen ubiquitination and chromatin structure on the dynamic properties of the Y-family DNA polymerases. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5193–5202. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crosetto N, et al. Human Wrnip1 is localized in replication factories in a ubiquitin-binding zinc finger-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35173–35185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803219200. c17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]