Abstract

We report the identification of male-killing Spiroplasma in a wild-caught female Drosophila melanogaster from Uganda, the first such infection to be found in this species outside of South America. Among 38 female flies collected from Namulonge, Uganda in April, 2005, one produced a total of 41 female offspring but no males. PCR testing of subsequent generations revealed that females retaining Spiroplasma infection continued to produce a large excess of female progeny, while females that had lost Spiroplasma produced offspring with normal sex ratios. Consistent with earlier work, we find that male-killing and transmission efficiency appear to increase with female age, and we note that males born in sex ratio broods display much lower survivorship than their female siblings. DNA sequence comparisons at three loci suggest that this Spiroplasma strain is closely related to the male-killing strain previously found to infect D. melanogaster in Brazil, though part of one locus appears to show a recombinant history. Implications for the origin and history of male-killing Spiroplasma in D. melanogaster are discussed.

Keywords: Spiroplasma, male-killing, Drosophila melanogaster, Africa, migration

Introduction

Drosophila melanogaster has served as a model organism in many areas of evolutionary genetics, but until recently the study of male-killing endosymbionts in this species was limited by the absence of a naturally occurring male-killing infection. Wolbachia, which causes male-killing in some species of Drosophila (e.g. Hurst et al. 2000; Dyer and Jaenike 2004), is present in many strains of D. melanogaster (Clark et al. 2005) but typically has only minor effects on fitness and cytoplasmic incompatibility (Hoffmann et al. 1998), and has not been observed to skew sex ratios. Recently, however, evidence for a maternally inherited male-killing factor was reported for a natural population of D. melanogaster from Brazil (Montenegro et al. 2000). Further research identified this male-killer as a member of the Spiroplasma poulsonii clade (Montenegro et al. 2005). Members of this group of bacteria had been known to cause male-killing in various species of the D. willistoni group (summarized in Williamson and Poulson 1979). The close relationship between the male-killing strains infecting D. nebulosa (a Neotropical species of the D. willistoni group) and D. melanogaster suggested the hypothesis of a recent horizontal transfer of Spiroplasma infection from the former species to the latter (Montenegro et al. 2005), occurring since the establishment of D. melanogaster in the Americas within the past few hundred years (David and Capy 1988). Research on D. melanogaster transinfected with the D. nebulosa strain of S. poulsonii has indicated that the male-killing activity of Spiroplasma relies on a functional dosage compensation system in the host (Veneti et al. 2005). The presence of naturally-occurring male-killing in D. melanogaster should offer additional insights into the molecular and evolutionary dynamics of male-killing.

We report the finding of a wild-caught female D. melanogaster collected in Uganda that produced exclusively female offspring. Crosses involving these female offspring indicated the presence of a male-killing endosymbiont, and subsequent DNA sequencing revealed a strain of Spiroplasma closely related to the male-killing strain infecting D. melanogaster in Brazil. Our findings reveal that male-killing Spiroplasma in D. melanogaster is present on at least two continents, suggesting that hypotheses for the origin of this infection may need to be re-assessed.

Materials and methods

Collection of the sex ratio strain

A total of 38 wild-caught D. melanogaster females were collected from Namulonge, Uganda in April, 2005, and used to initiate separate isofemale lines. In all but one case, the first generation offspring of these females initiated successful laboratory cultures, and an examination of these progeny revealed no apparent deviations from 50:50 sex ratios for any of these 37 lines. The exception was one wild-caught female that produced 41 offspring, all of them female.

Initial crosses to determine the cause of sex ratio distortion

The absence of male offspring is unlikely to be a product of chance (P < 10−12 , given 50:50 expectation), but might be attributable to a male-killing endosymbiont, sex ratio meiotic drive, or male-lethal mutations, and these explanations offer contrasting predictions for crosses involving the F1 female offspring. If a maternally inherited male-killing endosymbiont is responsible, the F1 females should produce an excess of femal1 e F2 offspring. If the cause is meiotic drive, there should be no sex ratio skew in the F2 offspring, because X versus Y chromosome drive should only affect the male parent’s gametes. With regard to male-lethal mutations, the prediction would depend on the inheritance of the mutation(s) and the parental genotypes, but the sex ratio trait would be expected to segregate in subsequent crosses.

F1 females from the sex ratio line (Ug-SR) were crossed to males from different Uganda isofemale lines (Ug11 and Ug12), or to males from laboratory stocks carrying balancer chromosomes (Fm7a X chromosome balancer, MDB second and third chromosome balancer, and TM6 third chromosome balancer), and the sex ratio of offspring was recorded. These crosses were started at various times, with F1 females between three and six weeks of age. These and all subsequent crosses were performed at 24°C using standard Drosophila medium. The Ug-SR F2 flies used for all subsequent crosses and testing were from Ug11 fathers, and in general, the Ug-SR line was maintained by mating Ug-SR females to Ug11 males.

PCR testing for potential male-killing bacteria

In testing for Wolbachia, the ftsZ (Werren et al. 1995) and wsp (Zhou et al. 1998) loci were used, with infected D. recens and uninfected D. subquinaria serving as controls. To test for Spiroplasma, the Spoul, spoT, and P58 loci (Montenegro et al. 2005) were used, with infected and uninfected strains of D. nebulosa serving as controls. Initial PCR testing used individual 1 to 2 day old female flies from Ug-SR and from one other Uganda isofemale line (Ug11). Additional PCR testing used one individual female fly from each of nine additional Uganda isofemale lines (age not controlled), along with 7 to 8 week old Ug-SR F2 females.

Antibiotic treatment and subsequent testing

Twenty 1 to 2 day old Ug-SR F2 females were crossed to Ug11 males (in separate vials). Ten cross vials contained the antibiotic tetracycline (designated as “T” lines), while the other ten contained normal, untreated medium (designated as “N” lines). Flies from the second generation of tetracycline treatment (or non-treatment) were PCR-tested for Wolbachia and Spiroplasma at approximately five weeks of age.

A final set of crosses allowed for the comparison of three infection categories: “T” flies negative for both Wolbachia and Spiroplasma, “N” flies positive for Wolbachia but negative for Spiroplasma, and “I” flies with positive infection status for both symbionts (maintained by crossing Ug-SR females at six weeks of age). Six week old females from each of these three infection categories were crossed to Ug11 males, and offspring sex ratios were observed for three replicates of each cross type.

Egg hatch rate and viability

Two analyses were performed to assess the stage-specific viability of Ug-SR female and male offspring. First, we placed four 5 week old Ug-SR females in separate vials containing normal yeast medium for 24 hours. The numbers of eggs laid, pupa formed, and adults eclosed were counted for each vial. Second, we allowed females to lay eggs on grape juice medium, then transferred 25 eggs to an adhesive surface and covered them with mineral oil. Following egg hatch, the number of larva were counted.

Sequencing of Wolbachia and Spiroplasma loci

In order to assess the relationship between symbionts infecting Ug-SR and those found to infect other D. melanogaster, we obtained sequence data for each of the Wolbachia and Spiroplasma loci listed above, except that we sequenced the more rapidly evolving fru locus instead of Spoul (Montenegro et al. 2005). The DNA sequences obtained were then compared to those obtained by Montenegro et al. (2005). To test for recombination at the p58 locus, the MaxChi implementation (Posada and Crandall 2001) of the method proposed by J. M. Smith (1992) was used. DNA Sequences were deposited in Genbank under accession numbers DQ445726-DQ445729.

Results

Initial crosses documenting inheritance of the male-killing factor

Upon discovering a wild-caught female D. melanogaster from Uganda that produced 41 female offspring but no males, we crossed these F1 females to males from a variety of genetic backgrounds (Table 1). The first few crosses, established when F1 females were about three weeks old, show a strong bias toward female offspring, but significant numbers of male offspring were also produced (Table 1). Interestingly, over half of these male offspring (18 out of 32) died within a week of the date of first eclosion, while only 7 out of 165 females died during this period (Table 1). Subsequent crosses, started when F1 females were about one month in age or older, show a more severe sex ratio skew, with nearly 100% female offspring (Table 1). These results were consistent with the endosymbiont hypothesis for male-killing, and suggested that maternal age might influence the degree of sex ratio skew.

Table 1.

Sex ratios and short term survival of F2 offspring

| Female Age (d) | Male (replicate) | Female Offsp. | Male Offsp. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | Ug11 (A) | 38 (37) | 15 (8) |

| 22 | MDB | 60 (54) | 5 (0) |

| 22 | TM6 | 67 (67) | 12 (6) |

| 25 | Fm7a (A) | 5 | 1 |

| 30 | Fm7a (B) | 26 | 0 |

| 34 | Ug11 (B) | 39 | 0 |

| 34 | Ug11 (C) | 62 | 0 |

| 34 | Ug11 (D) | 6 | 0 |

| 34 | Ug11 (E) | 50 | 0 |

| 34 | Ug11 (F) | 4 | 0 |

| 34 | Ug11 (G) | 43 | 0 |

| 34 | Ug11 (H) | 3 | 0 |

| 34 | Ug11 (I) | 14 | 1 |

| 35 | Fm7a (C) | 70 | 0 |

| 37 | F2 | 12 | 0 |

| 39 | Ug12 (A) | 60 | 0 |

| 39 | Ug12 (B) | 14 | 0 |

| 40 | Ug12 (C) | 7 | 0 |

| TOTAL OFFSPRING: | 580 | 34 | |

Female Age refers to the estimated age of the F1 Ug-SR female used for this cross (precise ages for each fly were not known, but we inferred that all of them eclosed within a few days of April 15, 2005). Male refers to the male parent used in the cross: Ug11 and Ug12 refer to Uganda isofemale lines from the same collection as Ug-SR that did not show a sex ratio bias; MDB, TM6, and Fm7a are laboratory balancer stocks with a presumable cosmopolitan genetic background; F2 refers to a male offspring from the Ug11 (A) cross that was back-crossed to a Ug-SR F1 female. The number of male and female offspring collected for each cross is reported. Finally, for the first three crosses, we also report (in parentheses) the number of females and males still alive one week after first eclosion.

PCR testing for the presence of Wolbachia and Spiroplasma

PCR using Wolbachia and Spiroplasma loci allowed Ug-SR and other Uganda isofemale lines (including Ug11) to be tested for infection by these endosymbionts. In the first round of PCR testing, using 1 to 2 day old female flies, clear amplification for the ftsZ and wsp loci provided evidence that both Ug-SR and Ug11 were infected by Wolbachia. For Spiroplasma, no amplification was observed at the Spoul locus for the four Ug11 females tested, but four out of six Ug-SR females gave varying degrees of amplification success. Additional PCR testing of nine additional Uganda isofemale lines gave clear evidence of Wolbachia infection in all lines (again using ftsZ and wsp), but no evidence for Spiroplasma infection in any of these lines (using Spoul and spoT).

To verify the Spiroplasma infection status of Ug-SR, we tested much older F2 females (age 7 to 8 weeks) using Spoul, spoT, and P58. All three Spiroplasma loci were successfully amplified in all six Ug-SR F2 females tested. Testing these same Ug-SR females with Y chromosome primers offered no evidence that any of them were feminized genetic males. Based on the above results, Wolbachia infection appears to be a very common condition within this population sample (95% C.I. for 11/11 is [0.7412, 1]), while Spiroplasma is only observed in the sex ratio line (95% C.I. for 1/38 is [0.0047, 0.1349]). The latter proportion could represent an underestimate, since additional Spiroplasma-infected wild-caught females in our sample might have gone undetected if male-killing was incomplete. However, the issue of reporting bias might suggest that our figure is an overestimate (many isofemale lines of D. melanogaster have previously been collected from tropical Africa without reports of Spiroplasma infection). The amplification success of Spiroplasma loci appears to depend on the age of the fly, which might be expected if Spiroplasma titer is increasing over the lifetime of the host, as demonstrated by Anbutsu and Fukatsu (2003).

Effect of antibiotic curing on sex ratios

We tested for Wolbachia and Spiroplasma in ten replicate lines that had been treated with tetracycline for two generations (“T” lines), and in ten replicate lines that received no antibiotic treatment (“N” lines). In both cases, these crosses were started with 1 to 2 day old Ug-SR F2 females, while PCR was done using six week old females from the second generation of treatment. For the “T” crosses, no amplification for FtsZ, wsp, Spoul, spoT, or P58 was observed for any of the ten cross replicates. Thus, antibiotic treatment appears to have cured the flies of both symbionts. For the “N” crosses, amplification of FtsZ and wsp was observed for all ten cross replicates. However, no amplification was observed for any of the Spiroplasma loci in any “N” cross replicate. Thus, while the “N” crosses maintained Wolbachia infection, Spiroplasma was apparently lost, possibly because the Ug-SR F2 female flies were crossed at a young age, and Spiroplasma titer may not yet have been high enough to ensure transmission to their offspring. This explanation is also consistent with the study of Montenegro et al. (2000), which concluded that Spiroplasma transmission rate increases with female age.

To observe the effect of endosymbiont loss on Ug-SR sex ratios, crosses wer1 e established with six week old females from the “T” and “N” lines described above, and from lines still infected with both endosymbionts (“I” lines). The percent female offspring for each cross type was: 51% for “T” crosses (50 females, 48 males), 53% for N” crosses (66 females, 59 males), and 100% for “I” crosses (70 females, 0 males). Thus, only the flies infected with Spiroplasma generated the sex ratio phenotype.

Analysis of stage-specific viability

The progeny of 5 week old Ug-SR females were monitored at successive life stages (Table 2). In three out of four cases, the number of pupae was approximately half number of eggs, and all of the adult offspring were female. For progeny of the fourth female, all 33 eggs developed into viable adults, 19 of which were male. Thus, one female apparently lost male-killing, and its progeny showed 100% egg to adult viability. The reduced viability of progeny of the other three females is apparently due to the mortality of male offspring as embryos or larvae. To determine whether male killing occurred at the embryonic or larval stage, 25 additional eggs from 5 week old Ug-SR females were monitored for hatch rate. Larvae emerged from 12 of these eggs, suggesting that male mortality had occurred at the embryo stage, which is consistent with earlier work on male-killing Spiroplasma (e.g. Counce and Poulson 1962).

Table 2.

Stage-specific viability of Ug-SR progeny

| Female | Eggs | Pupae | Female adults | Male adults |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 48 | 24 | 23 | 0 |

| B | 38 | 21 | 21 | 0 |

| C | 36 | 13 | 13 | 0 |

| D | 31 | 31 | 12 | 19 |

Progeny of four 5 week old Ug-SR females (designated A through D), were monitored. For each female, the number of eggs was recorded, and as were the numbers of pupae and female and male adults that subsequently developed.

DNA sequence comparisons of endosymbiont loci

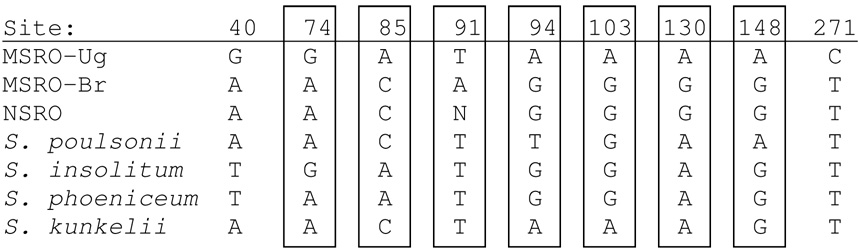

The Wolbachia sequences obtained from Ug-SR for ftsZ and wsp were identical to those previously reported for Wolbachia infecting D. melanogaster. For Spiroplasma, we compared our Ug-SR sequences to those obtained from the male-killing strain found t1 o infect D. melanogaster in Brazil (Montenegro et al. 2005). Building on their notation, we refer to the Brazil strain as MSRO-Br and the Uganda strain as MSRO-Ug (with MSRO abbreviating “melanogaster sex ratio organism”). Two of the Spiroplasma loci, spoT and fru, which are 513 and 360 bp long, respectively, showed identical sequence in MSRO-Br and MSRO-Ug. For the third locus, P58, the 3’ two-thirds of this 800 bp locus were identical between these two strains, but the 5’ one-third (271 bp) had nine substitutions differentiating them (all were confidently verified by double-stranded sequencing), as shown in Figure 1. MaxChi analysis (Smith 1992, Posada and Crandall 2001) supported the hypothesis of recombination (P = 0.01, corrected for multiple comparisons) and identified MSRO-Ug as the recombinant sequence, selecting MSRO-Br and S. insolitum as putative parental sequences. The breakpoints given by MaxChi, 40 and 271, corresponded precisely to the region containing differences between MSRO-Br and MSRO-Ug.

Figure 1. Evidence for recombinant origin of a portion of the MSRO-Ug p58 sequence.

DNA sequence differences observed at the 800 bp p58 locus between MSRO-Ug and MSRO-Br, and the character states of other sequenced taxa at these sites. Sites exhibiting shared character states between MSRO-Ug and one or more of the latter four taxa are boxed. Except for MSRO-Ug, these data are from Montenegro et al. (2005).

Discussion

We have reported the observation of strong sex ratio skew in D. melanogaster from Uganda. The crosses and PCR testing described above implicated a male-killing endosymbiont, specifically a member of the genus Spiroplasma. Male-killing and transmission efficiency increased with female age: in our crosses, 4 to 6 week old females produced nearly 100% female offspring, while younger females produced a more moderate sex ratio skew or failed to transmit Spiroplasma to their offspring. Males produced in sex ratio broods showed low short-term survivorship, consistent with the work of Counce and Poulson (1966), suggesting that they may have been harmed by the male-killing process.

The identical nature of most sequences compared between the strains of Spiroplasma infecting D. melanogaster in Uganda (MSRO-Ug) and Brazil (MSRO-Br), especially the rapidly evolving fru locus, supports a close relationship between these strains. However, the dissimilarity observed at the 5’ end of the P58 locus suggests a recombinant origin for this segment, a conclusion supported by the MaxChi analysis described above. The source of the recombinant portion of the MSRO-Ug P58 locus is uncertain. At seven of the nine sites differing between MSRO-Br and MSRO-Ug, the nucleotide observed for MSRO-Ug is shared by one or more of the other Spiroplasma taxa (Figure 1) sequenced by Montenegro et al. (2005), but none match MSRO-Ug at all seven sites. Thus, one possibility is that since diverging from a common ancestor with the MSRO-Br strain, a member of the MSRO-Ug lineage incorporated a homologous foreign DNA segment (possibly from another “species” of Spiroplasma) that included part of the P58 locus. A second possibility, suggested by the observation that P58 is part of a multigene family (Fletcher et al. 1998), is that the MSRO-Ug P58 allele might have been formed via intergenic recombination with a paralogous gene sequence.

Of the nine DNA sequence differences between the MSRO-Br and MSRO-Ug P58 alleles, only site 74 leads to an amino acid change (aspartate in MSRO-Ug and S. insolitum, asparagine in each of the other taxa examined). Since P58 encodes a membrane-bound surface protein (Fletcher et al. 1998), and such proteins may function in host cell adhesion and avoidance of immune recognition (Wise 1993), it could be interesting to test whether this charge-altering difference has any effect on the above processes.

If the region containing the recombinant fragment in MSRO-Ug is excluded, 1402 identical nucleotides remain between MSRO-Br and MSRO-Ug, giving a 95% confidence interval of [0, 0.0027] for per-site divergence. We lack specific information about per-year divergence rates for these loci and taxa, but using a crude estimate of 0.5% divergence per million years (Ochman and Wilson 1987, Woolfit and Bromham 2003), we can only exclude divergence times greater than 540,000 years for the split between MSRO-Br and MSRO-Ug. Thus, our data is compatible with either a recent or a more ancient infection of Spiroplasma in D. melanogaster.

Based on identical sequences for the above three Spiroplasma loci in MSRO-Br and NSRO (nebulosa sex ratio organism), and also the presence of related Spiroplasma taxa in other Neotropical Drosophilids, Montenegro et al. (2005) suggested that the male-killing Spiroplasma found to infect D. melanogaster in Brazil was recently transferred from D. nebulosa, possibly via body mites or other parasites. Prior to this study, no incidence of male-killing had been found in D. melanogaster outside Brazil, so our finding of a closely related male-killing strain of Spiroplasma in Uganda D. melanogaster invites a re-examination of historical hypotheses for this infection.

The presence of male-killing Spiroplasma in African D. melanogaster is not inconsistent with the hypothesized South American origin of this infection. This scenario would require that one or more Spiroplasma-infected D. melanogaster migrated from South America back to sub-Saharan Africa, which contains ancestral range of the species (Lachaise 1988). Such migration is made plausible by trans-oceanic shipping, and P-elements provide a precedent for selfish genetic elements spreading from New World to Old World in D. melanogaster (Anxolabéhère et al. 1988). But African and South American populations maintain very different levels of genetic diversity (Begun and Aquadro 1995), which suggests that levels of recent migration have not been excessive.

The main evidence supporting the South American origin hypothesis is the relationship between the Spiroplasma strain infecting D. melanogaster and those infecting other Neotropical Drosophilids. However, due to the low frequency at which Spiroplasma persists, along with the limited number species that have been probed for Spiroplasma infection, there many be many more infected species than are currently known. Thus, a more complete search for Spiroplasma-infected Drosophilids, particularly outside the Neotropics, would be helpful in evaluating this hypothesis.

If South America was the origin of male-killing Spiroplasma in D. melanogaster, it is interesting that we have identified this symbiont in a population sample from inland eastern Africa. Since Uganda is unlikely to be the point of first arrival in Africa for immigrant D. melanogaster from South America, the presence of male-killing Spiroplasma in this location could indicate a recent and rapid spread of this symbiont within tropical Africa. Such an expansion might offer the opportunity to study the selective and environmental constraints governing the spread of a male-killing endosymbiont, and additional host shifts in Africa might be possible.

Although we neither confirm nor reject a South American origin, the presence of male-killing Spiroplasma in Uganda D. melanogaster suggests an alternate possibility, that D. melanogaster might have harbored this endosymbiont prior to its spread from tropical Africa. Much of the New World is thought to have been colonized primarily by D. melanogaster from Europe (David and Capy 1988). However, because Spiroplasma does not transmit itself effectively at temperatures below 20°C (Montenegro et al. 2004), it is more likely that Spiroplasma-infected flies would have migrated directly from sub-Saharan Africa to the Neotropics. This seems plausible, since it has been argued that many New World populations of D. melanogaster have at least a small portion of African ancestry (Caracristi and Schlötterer 2003). Once the MSRO strain of Spiroplasma reached South America, it might have been horizontally transferred to D. nebulosa, via the same potential mechanism as cited by Montenegro et al. (2005). If this African origin hypothesis is correct, we might expect to find additional African species of Drosophila infected with Spiroplasma. Also, we would still have to posit an earlier transatlantic migration of a Spiroplasma poulsonii-like strain to account for the similarities between (the putatively African) MSRO and other members of the Spiroplasma poulsonii clade found in Neotropical Drosophilids.

Greater worldwide sampling of Drosophilid-infecting Spiroplasmas is required to differentiate the above hypotheses. Regardless of the origin of male-killing Spiroplasma in D. melanogaster, its presence in distinct geographic areas should allow a comparison of the genetic and phenotypic divergence of these strains.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Jaenike for providing flies for positive and negative PCR controls and James Ogwang for collecting flies from Uganda on our behalf. We also thank members of the Aquadro and Jaenike labs, along with two anonymous reviewers, for helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant GM36431 to C.F.A. and a National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant 0411730 to J.E.P. and C.F.A.

References

- Anbutsu H, Fukatsu T. Population dynamics of male-killing and non-male-killing Spiroplasmas in Drosophila melanogaster. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2003;69:1428–1434. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.3.1428-1434.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anxolabéhère D, Kidwell MG, Periquet G. Molecular characteristics of diverse populations are consistent with the hypothesis of a recent invasion of Drosophila melanogaster by mobile P elements. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1988;5:252–269. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begun DJ, Aquadro CF. Molecular variation at the vermilion locus in geographically diverse populations of Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans. Genetics. 1995;140:1019–1032. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.3.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caracristi G, Schlötterer C. Genetic differentiation between American and European Drosophila melanogaster populations could be attributed to admixture of African alleles. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003;20:792–799. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark ME, Anderson CL, Cande J, Karr TL. Widespread prevalence of Wolbachia in laboratory stocks and the implications for Drosophila research. Genetics. 2005;170:1667–1675. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.038901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counce SJ, Poulson DF. Developmental effects of the sex-ratio agent in embryos of Drosophila willistoni. J. Exp. Zool. 1962;151:17–31. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401510103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counce SJ, Poulson DF. The expression of maternally-transmitted sex ratio condition (SR) in two strains of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetica. 1966;37:364–390. doi: 10.1007/BF01547143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David JR, Capy P. Genetic variation of Drosophila melanogaster natural populations. Trends Genet. 1988;4:106–111. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(88)90098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer KA, Jaenike J. Evolutionarily stable infection by a male-killing endosymbiont in Drosophila innubila: molecular evidence from the host and parasite genomes. Genetics. 2004;168:1443–1455. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.027854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher J, Wayadande A, Melcher U, Ye F. The phytopathogenic mollicute-insect vector interface: A closer look. Phytopathology. 1998;88:1351–1358. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.12.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann AA, Hercus M, Dagher H. Population dynamics of the Wolbachia infection causing cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1998;148:221–231. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.1.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst GDD, Johnson AP, Schulenburg JHGvd, Fuyama Y. Male-killing Wolbachia in Drosophila: a temperature-sensitive trait with a threshold bacterial density. Genetics. 2000;156:699–709. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.2.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachaise D, Cariou M, David JR, Lemeunier F, Tsacas L, Ashburner M. Historical biogeography of the Drosophila melanogaster species subgroup. In: Hecht MK, Wallace B, Prance GT, editors. Evolutionary biology. Vol. 22. New York: Plenum Press; 1988. pp. 159–225. [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro H, Souza WN, Leiteà DS, Klaczko LB. Male-killing selfish cytoplasmic element causes sex-ratio distortion in Drosophila melanogaster. Heredity. 2000;85:465–470. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2000.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro H, Klaczko LB. Low temperature cure of a male killing agent in Drosophila melanogaster. J Invert Path. 2004;86:50–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro H, Solferini VN, Klaczko LB, Hurst GDD. Male-killing Spiroplasma naturally infecting Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Mol. Biol. 2005;14:281–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2005.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochman H, Wilson AC. Evolution in bacteria: Evidence for a universal substitution rate in cellular genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 1987;26:74–86. doi: 10.1007/BF02111283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Crandall KA. Evaluation of methods for detecting recombination from DNA sequences: Computer simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:13757–13762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241370698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JM. Analyzing the mosaic structure of genes. J. Mol. Evol. 1992;34:126–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00182389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veneti Z, Bentley JK, Koana T, Braig HR, Hurst GDD. A functional dosage compensation complex required for male killing in Drosophila. Science. 2005;307:1461–1463. doi: 10.1126/science.1107182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werren JH, Zhang W, Guo LR. Evolution and phylogeny of Wolbachia: reproductive parasites of arthropods. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1995;261:55–63. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DL, Poulson DF. Sex-ratio organisms (Spiroplasmas) of Drosophila. In: Whitcomb RF, Tully JG, editors. The Mycoplasmas. vol. 3. New York: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 175–208. [Google Scholar]

- Wise KS. Adaptive surface variation in mycoplasmas. Trends Microbiol. 1993;1:59–63. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(93)90034-O. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolfit M, Bromham L. Increased rates of sequence evolution in endosymbiotic bacteria and fungi with small effective population sizes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003;20:1545–1555. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Rousset F, O'Neill S. Phylogeny and PCR-based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1998;265:509–515. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]