Abstract

Praziquantel (PZQ) is the drug of choice for schistosomiasis and probably is the only highly effective drug currently available for treating schistosomiasis-infected individuals. The mode of action of PZQ involves increasing the calcium uptake of the parasite, resulting in tegumental damage and death of the parasite. Despite its remarkable function, the target of PZQ has not been identified yet. To begin to understand where PZQ acts, in this study we expressed the cDNA library of Schistosoma mansoni on the surface of T7 bacteriophages and screened this library with labeled PZQ. This procedure identified a clone that strongly bound to PZQ. Subsequent DNA analysis of inserts showed that the clone coded for regulatory myosin light chain protein. The gene was then cloned, and recombinant S. mansoni myosin light chain (SmMLC) was expressed. Immunoblot analysis using antibodies raised to recombinant SmMLC (rSmMLC) showed that SmMLC is abundantly expressed in schistosomula and adult stages compared to the amount in cercarial stages. In vitro analyses also confirmed that PZQ strongly binds to rSmMLC. Further, peptide mapping studies showed that PZQ binds to amino acids 46 to 76 of SmMLC. Immunoprecipitation analysis confirmed that SmMLC is phosphorylated in vivo upon exposure to PZQ. Interestingly, significant levels of anti-SmMLC antibodies were present in vaccinated mice compared to the amount in infected mice, suggesting that SmMLC may be a potential target for protective immunity in schistosomiasis. These findings suggest that PZQ affects SmMLC function, and this may have a role in PZQ action.

Praziquantel (PZQ) is the drug of choice for human and animal schistosomiasis, a parasitic infection that is acquired through water contact (8). Adult parasites residing inside the blood vessels produce eggs, which when lodged in the tissues will generate a severe granulomatous reaction leading to fibrosis. A single oral dose of PZQ is more than 95% effective in producing a total resolution of the cellular reaction and fibrosis that surrounds the eggs in the tissues (19, 29). Toxicological data suggest that PZQ is a fairly safe drug for mass treatment against human schistosomiasis (20). Studies of the mechanism of action of this drug against Schistosoma mansoni suggest that PZQ causes progressive contraction of the longitudinal musculature of the worms (10), dislodging them from the mesenteric blood vessels to the liver, which is followed by the death and disintegration of the parasites. In vitro studies also show that PZQ is lethal for the parasites especially at the skin, young adult, and adult stages. When parasites are incubated in PZQ, the drug gets distributed uniformly throughout the surface (1). Ultrastructural studies show intensive vacuolization of the tegument within 5 min after exposure to PZQ (4). When this happens inside the host, cells (mainly eosinophils) attach to the tegumental vacuoles and enter into the interior of the parasites within 4 h after treatment and destroy the parasite. The subsequent granulomatous reaction that develops around the dead parasites causes the complete disintegration of the parasite within 2 weeks after treatment. The resolution of the fibrotic lesions around the egg may, however, take longer (28). Thus, PZQ can reverse the pathology associated with schistosomiasis, depending upon the stage of the disease (9, 10, 13-16, 20).

Concurrent with this disruption to the tegument, there is a significant influx in Ca2+ in the worms following treatment with PZQ (5, 12). Even though there appears to be no clear correlation between the influx of calcium and the death of the parasites (22), the voltage-gated calcium channel may have a role in PZQ-mediated action (12). Several other molecules such as glutathione (9), adenosine receptor (2), glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored antigens (13), phosphoinositide (31), and actin (25) in the parasite have been reported as the target of PZQ.

Given the discrepancy in the literature, in this study we decided to identify the binding partner of PZQ in the parasite genome. The technique of displaying peptides or proteins on the surfaces of bacteriophages is a powerful approach to screen proteins of interest. Since the protein displayed on the surface of the phage is physically linked to the genetic material that codes for it, the gene that codes for the displayed protein can be easily cloned from the phages. This method is simple, efficient, and sensitive enough that it allows us to clone genes of interest from phages that express even picomolar quantities of the protein (6). In this study, we used a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled PZQ to screen the phage-displayed cDNA library of S. mansoni schistomula. We also characterized the clones that bound to PZQ.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Display of S. mansoni gene products on T7 bacteriophages.

A Uni-ZAP XR cDNA library of the schistosomula stages of S. mansoni was obtained from Philip LoVerde, Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research, San Antonio, Texas. This library was used as a template for generation of a cDNA library by PCR amplification using primers flanking the cDNA inserts. PCR parameters were as follows: 95°C of denaturation for 30 s, 55°C of primer annealing for 30 s, and 72°C of primer extension for 3 min, cycled 30 times. A final extension of 5 min was performed at 72°C before storing the samples at 4°C. PCR was performed with pfuTurbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene, Lajolla, CA) to enhance the fidelity, sensitivity, and yield of PCR products. The forward primer for PCR was T3 primer with a sequence of 5′ AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGG 3′, whereas the reverse primer was T7 promoter primer with a sequence of 5′ GAAATACGACTCACTATAGGG 3′. PCR products were purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and size fractionated to select products of >300 bp in length, by using CHROMA SPIN columns (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). The PCR products were digested with EcoRI and HindIII enzymes and ligated to a similarly digested phage display vector T7Select 1-1 cloning system (Novagen, Madison, WI). The library was then packaged in vitro, titers were determined, and the library was amplified as per the procedures outlined in the T7Select system manual. Length and frequency of insertions were verified by PCR amplification of randomly selected clones.

Biochemical modification of PZQ.

PZQ was purchased from Alexis Corporation (San Diego, CA). Since PZQ has no functional group, it cannot be directly labeled. Therefore, an amino group was first added to PZQ using methods described by Mitsui and Arizono (18). In their studies, they first added an amino group to PZQ through a biochemical reaction and then conjugated HRP to this amino group. This labeled PZQ was then used in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) to measure anti-PZQ antibodies in the sera of mice immunized with bovine serum albumin (BSA)-conjugated PZQ. Their studies showed that the labeling technique did not affect the structural conformation of PZQ. Therefore, we used the same labeling technique in our studies. Briefly, 2-[4-(aminomethyl)cyclohexylcabonyl]1,2,3,6,7,11b-hexahydro-4H pyrazino[2,1-a]isoquinoline-4-one-NH2 was synthesized first and then combined with hydrolyzed PZQ to yield PZQ-NH.2TsOH.

HRP labeling of PZQ.

The modified PZQ-NH.2TsOH could then be labeled with HRP. For labeling, we coupled 10 mg of PZQ-NH.2TsOH to 1 mg of EZ-Link plus activated peroxidase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) as described by the manufacturer. Subsequently, the PZQ-HRP conjugate was then purified using a D-Salt dextran desalting column (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were stored at 4°C until use.

Biopanning.

The strategy used for biopanning the cDNA library of S. mansoni to select PZQ binding specific clones was similar to that previously described by our laboratory (11). Wells of a high binding microtiter plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were coated overnight at 4°C with 1 μg/well of polyclonal anti-HRP antibodies. After washing the wells with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST), nonspecific sites were blocked with 5% BSA for 1 h at 37°C. HRP-labeled PZQ (100 μl at 1 mg/ml) was then added to the wells and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The unbound HRP-PZQ was discarded by washing five times with PBST. To isolate PZQ-interacting clones, 100 μl of the T7Select library (containing 1× 1011 PFU/ml) was added to the wells, which were coated with PZQ-HRP and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The unbound phage was discarded and washed five times with PBST to remove weakly bound phage clones. The bound phages were then eluted with 200 μl of T7 elution buffer (Tris-buffered saline [TBS] containing 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) and amplified by infecting Escherichia coli host BLT5403. The amplified phages were then subjected to another four rounds of panning as above, to enrich the clones that highly and specifically bound to PZQ.

Sequencing and analysis.

After four rounds of biopanning, the final enriched PZQ-specific clones were plated on agar and single pure plaques were isolated. The cDNA inserts in these plaques were then amplified by PCR using primers flanking the inserts. PCR primers were as follows: T7SelectUP, 5′ GGAGCTGTCGTATTCCAGTC 3′; and T7SelectDown primer, 5′ AACCCCTCAAGACCCGTTTA 3′. PCR conditions were as follows: denaturation for 1 min at 94°C, primer annealing for 1 min at 50°C, and primer extension for 1 min at 72°C for a total of 30 cycles. QIAquick columns (Qiagen) were then used to purify the PCR products after a final extension for 5 min at 72°C. The nucleotide sequences of selected PCR products were determined at the DNA core facility of the University of Illinois Chicago. Sequences were analyzed by BLAST (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) searches with the GenBank database. Further analysis by multiple sequence alignment was performed using the ClustalW (www.ebi.ac.uk) program.

Construction of SmMLC expression vector.

The open reading frame (ORF) of SmMLC was cloned in the T7 expression vector, pRSET A (Invitrogen, Lajolla, CA). The forward PCR primer corresponded to the beginning of the ORF of SmMLC with the addition of an upstream in-frame BamHI restriction site (5′ CGCGGATCCATGGTTGACTTAAGTGAA 3′). The reverse primer corresponded to the 3′ end of the SmMLC ORF flanked by an EcoRI restriction site (5′ CCGGAATTCTTAACTAGTTACTCGAGT 3′). The PCR parameters were 95°C of denaturation for 30 s, 55°C of primer annealing for 30 s, and 72°C of primer extension for 30 s, and the cycle was repeated 30 times. A final extension of 5 min was performed at 72°C before storing the samples at 4°C. The PCR products obtained were digested with BamHI and EcoRI enzymes and ligated to the similarly digested T7 expression vector pRSET A. Insert DNA was sequenced to ensure the authenticity of the cloned nucleotide sequence on both the strands.

Expression and purification of rSmMLC.

A recombinant construct of SmMLC (rSmMLC) in the T7 expression vector was maintained in the XL-1 blue strain (Stratagene). For expression, the recombinant plasmid was transformed into BL21(DE3) containing pLysS (Invitrogen) to minimize toxicity due to the protein. When the optical density at 600 nm of the cultures reached 0.6, 1 mM of IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was added to the cultures to induce gene expression, and they were incubated for an additional 3 h. Total proteins were separated in a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and the presence of histidine-tagged protein was confirmed using a penta-His antibody (Qiagen). Subsequently, the histidine-tagged recombinant proteins were purified using immobilized cobalt metal affinity column chromatography (Clontech), as per the manufacturer's recommendations. The purity of the recombinant protein was subsequently determined by separating the protein in a 12% SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R250.

Immunization of mice with rSmMLC.

Male BALB/c mice weighing 10 to 15 g purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) were used in these experiments. All animals were treated in accordance with an approved institutional protocol. Mice were immunized subcutaneously with 5 μg of rSmMLC in Gerbu adjuvant (Biotechnik Gmbh, Gaiberg, Germany). Three booster injections were given at two-week intervals using the same antigen dose. After the final booster dose, mice were bled, and sera were separated and stored at −20°C. Antibody titers in the sera were determined using an ELISA, and antibody reactivity was confirmed in a Western blot analysis.

Preparation of soluble antigens of S. mansoni.

Soluble proteins from different life cycle stages of S. mansoni (cercariae, schistosomula, and adults) were prepared as described previously (23). To prepare soluble extracts, parasites were homogenized in NET buffer (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4) in the presence of protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and the insoluble materials were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The soluble antigenic fraction in the supernatant was then collected and the protein amount estimated using a BCA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Stage-specific expression of SmMLC.

Levels of expressed SmMLC protein were evaluated in the soluble antigen preparations of S. mansoni using an immunoblot analysis. Briefly, S. mansoni worm homogenates were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Parasite antigens in the membrane were then probed with mouse anti-SmMLC (1:500 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing the membrane five times with TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST), HRP-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody (Pierce Biotechnology) was added at a 1:5,000 dilution and the color was developed by the enhanced chemiluminescence method (ECL) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). Purified rSmMLC was used as a positive control.

In vitro binding of PZQ to SmMLC.

To determine the binding of PZQ to rSmMLC, an ELISA-based binding assay was performed. Briefly, various concentrations of rSmMLC starting from 100 ng to 10 μg were coated onto the wells of a 96-well ELISA plate overnight at 4°C. After washing the plates five times with PBST, 100 μl of 5% BSA was added to block nonspecific sites. The plates were again washed with PBST, and HRP-labeled PZQ (1 μg/ml to 20 μg/ml) was added to the respective wells. After incubating the plates for 1 h at room temperature, the color was developed using an orthophenylenediamine (OPD) substrate. The optical density at 405 nm was determined calorimetrically in an ELISA plate reader.

Binding of PZQ to SmMLC was also determined by Western blot analysis. Approximately 5 μg of purified rSmMLC was separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking the nonspecific sites with 5% nonfat skimmed milk for 1 h at room temperature, the membrane was washed five times with TBST and probed with HRP-labeled PZQ (10 μg/ml) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing the membranes again with TBST, the signal was developed using an ECL kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Determination of the PZQ binding region in SmMLC.

A total of nine peptides (five nonoverlapping peptides and four overlapping peptides) of 26 to 31 amino acids (aa) in length were chemically synthesized at the Genscript Corporation (Scotch Plains, NJ). Details of the peptide sequence are given in Table 1. Briefly, wells of a 96-well plate were coated with 100 ng of the peptide, and an ELISA was performed as described above to determine the binding of HRP-labeled PZQ.

TABLE 1.

Details of the SmMLC peptides used in this study

| Peptide name | Peptide sequence | Peptide length |

|---|---|---|

| SmMLCaa1-30 | MVDLSEKDLNDVHEMFLLFDTKGDEKIEAK | 30 |

| SmMLCaa31-60 | DIGEVVRAMGLNPTESDIGKYGYQNNPNER | 30 |

| SmMLCaa61-90 | ISFESFVPIYHGLLKEQVEVDQETFIESFR | 30 |

| SmMLCaa91-120 | VFDKEDNGLISAAELRHLLTALGEKLRDNE | 30 |

| SmMLCaa121-146 | VDVLLSGLENSQGLVPYEAFVQRVMS | 26 |

| SmMLCaa15-45 | MFLLFDTKGDEKIEAKDIGEVVRAMGLNPTE | 31 |

| SmMLCaa46-76 | SDIGKYGYQNNPNERISFESFVPIYHGLLKE | 31 |

| SmMLCaa77-107 | QVEVDQETFIESFRVFDKEDNGLISAAELRH | 31 |

| SmMLCaa108-138 | LLTALGEKLRDNEVDVLLSGLENSQGLVPYE | 31 |

Immunoprecipitation and detection of phosphorylation of SmMLC.

Previous studies have shown that PZQ treatment causes irreversible muscle contraction in S. mansoni (1). Phosphorylation of MLC is believed to play an important role in the contraction of muscle cells (15, 16). To test whether PZQ has any effect on SmMLC phosphorylation status, we treated schistosomula with 20 μg/ml of PZQ for various time periods. Native SmMLC from untreated or treated schistosomula was immunoprecipitated using a Seize X protein A immunoprecipitation kit obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (catalog no. 45215). Briefly, 100 μg of mouse anti-SmMLC antibodies or preimmune serum was first allowed to bind to immobilized protein A columns for 15 min and washed with binding/wash buffer five times in a microcentrifuge at 3,500 rpm for 1 min. The bound antibodies were then cross-linked to protein A using disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS) cross-linker. The cross-linked antibodies were then used to immunoprecipitate SmMLC from schistosomula homogenates. Briefly, 100 μg of soluble antigens was incubated with the cross-linked antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The unbound antigens were removed by washing five times with wash buffer. The bound antigens were eluted with 200 μl of elution buffer.

The presence of serine/threonine phosphorylation of SmMLC in the eluted antigen was detected by staining with mouse monoclonal anti-phosphoserine/threonine antibody (BD Transduction Laboratories, Franklin Lakes, NJ) using an immunoblot analysis. Briefly, immunoprecipitated antigens were transferred onto nitrocellulose sheets and incubated with either anti-phosphoserine/threonine antibody (diluted 1:1,000) or mouse anti-SmMLC antibodies (1:500) for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation, blots were washed four times with TBST and probed with HRP-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody (1:5,000). Color was detected using an ECL substrate.

Analysis of SmMLC antibodies in mouse sera.

The presence of SmMLC antibodies in the sera of infected and vaccinated mice was evaluated using an ELISA as described previously (23). Briefly, wells of a 96-well plate were coated with 1 μg of rSmMLC. After blocking the nonspecific sites with 5% BSA, sera samples (diluted 1:100) collected from preimmune (n = 5), infected (n = 5), and vaccinated mice (n = 5) were added to the wells and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Wells were washed five times with PBST, and 100 μl of HRP-labeled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added. After incubating the plates for one hour at 37°C, the color was developed using OPD substrate (1 mg/ml). Absorbance was measured at 405 nm in a microtiter plate reader (Dynatech Laboratories Inc., Chantilly, VA).

Statistical analysis.

Data from these studies were compared using a Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks using the SigmaStat program (Jandel Scientific, San Rafel, CA). P of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The SmMLC nucleotide sequence reported here was deposited in GenBank under accession number AY510605.

RESULTS

Display of the cDNA library of S. mansoni on T7 bacteriophages.

Based on the PFU after in vitro packaging, it was calculated that the T7 phage display library of S. mansoni contained 3 × 108 independent clones. Amplification of the inserts from randomly selected clones revealed that the library contained >90% recombinants with an average insert size of >500 bp (data not shown). Taking into account the three possible reading frames and assuming that there are about 17,250 expressed genes in S. mansoni, the number of clones required to achieve 99% probability so that all the sequences are represented in the library is calculated by the following formula: N = ln(1 − P)/ln[1 − (1/n)], where N is the size of the library, P is the probability, and n is the estimated number of expressed genes. Based on the formula, to obtain 17,250 genes, the expected N would be 0.7 ×105. Since the size of the generated phage display library exceeds the statistically required number, it is highly likely that most of the expressed genes were represented in this library.

Sequence analysis of the PZQ-specific clones to identify the antigens.

About 10 clones were randomly selected from individual plaques. The DNA sequences of the inserts were then PCR amplified and analyzed on agarose gel to determine the sizes of the inserts (data not shown). These analyses showed that the 10 clones consisted of two groups of insets with sizes of ∼200 bp and ∼500 bp. Sequence analyses of these PCR products revealed that one clone is similar to the previously reported SmMLC from an adult stage (GenBank accession no. AAA29873) and the other one was a partial-length clone of the S. mansoni actin gene (accession no. AI021773). Six (60%) of the clones that bound to PZQ were SmMLC, and the remaining four (40%) clones that bound to PZQ were SmActin. Since SmMLC was the most frequent PZQ binding clone, SmMLC was chosen for further evaluation. The SmMLC cloned in this study showed significant similarity with the previously reported schistosomal MLCs in GenBank (Fig. 1). Phylogenetic analyses also showed that schistosome MLCs are closely related and distantly separated from mammalian MLC (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of SmMLC. Multiple alignments (ClustalW) of the aa sequences of the SmMLC family of proteins from S. mansoni (SmMLC1 from S. mansoni schistosomula stage [GenBank accession no. AY510605] and SmMLC2 from S. mansoni adult stage [accession no. AAA29873]), Schistosoma japonicum (SjMLC [accession no. AAP06506]), Caenorhabditis elegans (CeMLC [accession no. CAB03346]), human (HsMLC [accession no. NP_524144]), mouse (MmMLC [accession no. NP_067260]), and Drosophila melanogaster (DmMLC [accession no. NP_511049]). The aa positions are numbered above the aa sequences. Multiple alignment results show that MLCs from different species are highly identical to each other. “*” indicates identical aa; “:” indicates strongly similar aa; and “.” indicates weakly similar aa.

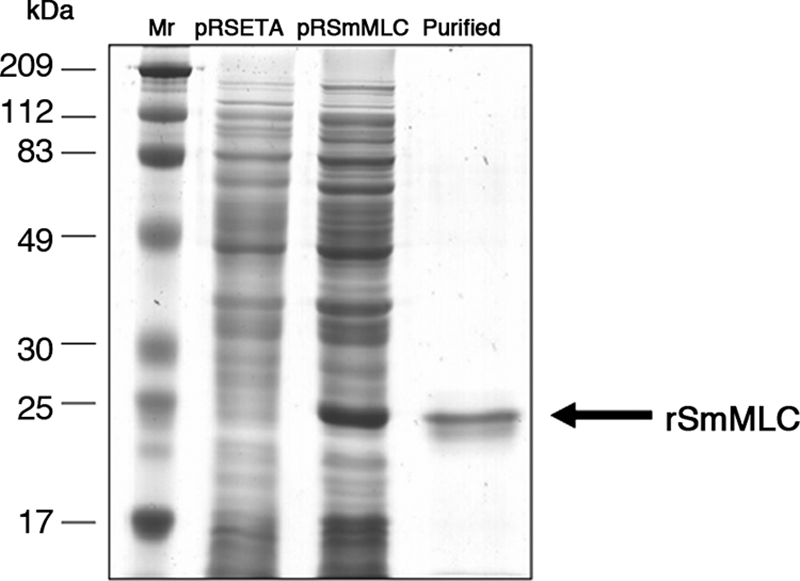

Expression of rSmMLC.

rSmMLC cloned in pRSET A was then expressed as a histidine-tagged fusion protein. The recombinant fusion protein with the histidine tag had a molecular mass of approximately 21 kDa (Fig. 2). SDS-PAGE analysis showed that expressed rSmMLC composed >10% of the total E. coli proteins. Subsequently, the recombinant protein was purified under native conditions using metal affinity column chromatography to near homogeneity (Fig. 2). The identity of the recombinant protein was further confirmed by immunoblotting using an anti-His antibody (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Expression and purification of SmMLC. Cultures of E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS containing pRSET A and pRSmMLC expression constructs were induced with IPTG. Following induction, rSmMLC was purified from the cultures using a cobalt metal affinity chromatography column. Approximately 1 μg of the purified protein was then separated in a 12% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R250. Lanes: Mr, protein molecular weight marker; pRSET A, crude lysate of BL21(DE3) pLysS culture carrying pRSET A induced with 1 mM IPTG; pRSmMLC, crude lysate of BL21(DE3) pLysS culture carrying pRSmMLC induced with 1 mM IPTG; and PURIFIED, rSmMLC protein purified by metal affinity chromatography from IPTG-induced cultures of BL21(DE3) pLysS carrying pRSmMLC.

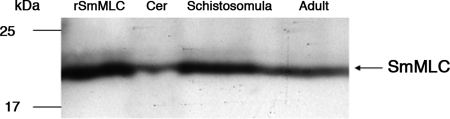

Stage-specific expression of SmMLC in different life cycle stages of S. mansoni.

Immunoblot analysis of the soluble protein extracts of the different life cycle stages of the parasite showed that the native SmMLC protein was expressed in all of the stages that we tested. Expression of SmMLC was higher in schistosomula and adult stages than in cercarial stages of the parasite. The mouse anti-SmMLC antibodies strongly reacted with a 21-kDa protein in the worm homogenates, as predicted (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Stage-specific expression of rSmMLC. Soluble protein extracts (10 μg/lane) from cercariae (Cer), schistosomula, and adult stages of S. mansoni were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with a mouse anti-SmMLC antibody. Recombinant SmMLC (rSMLC) was used as a positive control. An arrow indicates bands with strong immunoreactivity. Data shown are representative of one of three similar results.

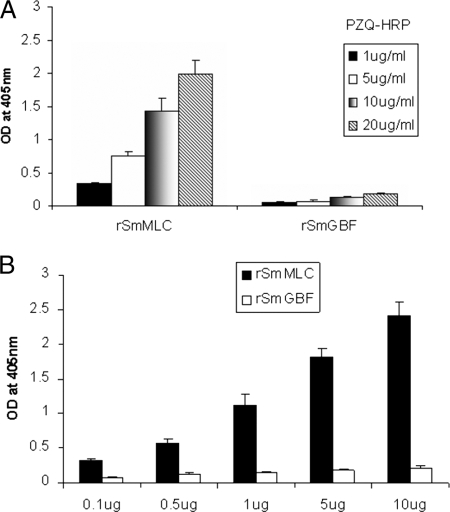

PZQ binds to rSmMLC.

PZQ binding to rSmMLC was confirmed by an ELISA. The results show that PZQ binds to rSmMLC in a dose-dependent manner. When increasing concentrations of PZQ were added to a fixed concentration of rSmMLC, increased binding of PZQ to rSmMLC occurred (Fig. 4A). Similarly, increasing the concentration of rSmMLC coated to the wells also resulted in increased PZQ binding (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that the binding is not nonspecific. Furthermore, a control recombinant protein, prepared under conditions similar to those for rSmMLC, failed to bind to PZQ, suggesting that the binding of PZQ to rSmMLC is specific.

FIG. 4.

(A) Dose-dependent binding of PZQ to rSmMLC. The binding of PZQ to rSmMLC was determined by ELISA. rSmMLC (1 μg)-coated wells were incubated with various concentrations of HRP-labeled PZQ (1 μg/ml to 20 μg/ml) for 1 h at room temperature. The results showed that PZQ binds to rSmMLC in a dose-dependent fashion. (B) PZQ binding kinetics with rSmMLC. Various concentrations of rSmMLC (0.1 μg to 10 μg/well) were coated and incubated with 10 μg/ml of HRP-labeled PZQ. These studies showed that PZQ strongly binds to rSmMLC at increasing concentrations. rSmGBF, a control recombinant protein, failed to bind to PZQ. OD, optical density.

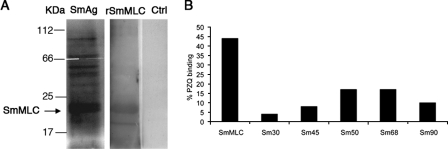

A Western blot analysis was also performed using rSmMLC to further confirm the binding of PZQ to SmMLC. These studies showed that PZQ bound to rSmMLC (Fig. 5A) but not to the control recombinant protein or BSA (data not shown). There were two bands visible in the blots, one broad band and a small band (lane 2). We do not know what the low-molecular-weight band is at this time. Since PZQ bound to the protein, we believe that it may be a degradative fragment of rSmMLC. Both the bands bound anti-His antibodies (data not shown). To further determine whether PZQ binds to native SmMLC, we performed another Western blot analysis using soluble proteins from the adult worm homogenate (Fig. 5A, lane 1). These studies showed that PZQ binds to more than one protein in the adult worm homogenate. One of these major bands matched with the molecular mass of rSmMLC. A semiquantitative analysis using ImageJ analysis software on the PZQ binding bands in the adult worm homogenate showed that the putative SmMLC is the most abundant PZQ binding protein in the adult worm homogenate (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

PZQ binds to native SmMLC. (A) S. mansoni-soluble worm homogenates (SmAg) and rSmMLC were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with HRP-labeled PZQ. The color was developed using an ECL reagent. rSmMLC incubated with HRP alone served as a control (Ctrl). (B) Binding of labeled PZQ to soluble SmAg proteins was determined semiquantitatively using ImageJ software. Percentages of PZQ binding to SmAg proteins are shown on the y axis, and the approximate molecular sizes of the native proteins that bind to PZQ are shown on the x axis. Image analyses show that a majority (∼45%) of labeled PZQ binds to SmMLC compared to the binding of other antigenic proteins.

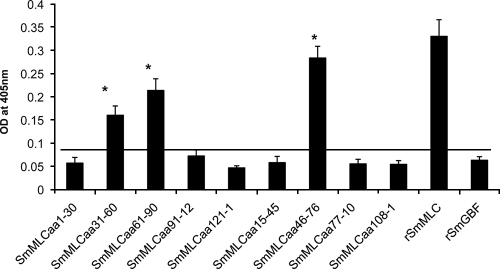

PZQ binds to the N-terminal region of SmMLC.

We then mapped the PZQ binding region in the SmMLC sequence by screening synthetic peptides. Nine peptides (five nonoverlapping and four overlapping peptides) of SmMLC were screened for PZQ binding using an ELISA. Out of the nine SmMLC peptides screened, three peptides (SmMLCaa31-60, SmMLCaa61-90, and SmMLCaa46-76) bound strongly to PZQ compared to the binding with other peptides of SmMLC (Fig. 6). These three peptides are located on the N terminus of the SmMLC protein. Of the three peptides that bound to PZQ, the intensity of the binding of SmMLCaa46-76 was most comparable to the binding of the full-length rSmMLC protein to PZQ (Fig. 6). Thus, our results suggest that the PZQ binding epitope of SmMLC potentially lies within the aa 46 to 76 region of SmMLC.

FIG. 6.

Mapping of the PZQ binding region in SmMLC. To determine the PZQ binding domain of SmMLC, synthetic peptides of SmMLC were evaluated for their binding to PZQ using an ELISA. Peptides (100 ng) of SmMLC were used for coating the wells. After blocking, the wells were incubated with 10 μg/ml of HRP-labeled PZQ for 1 h at room temperature. Binding was then detected by the addition of OPD substrate. The results show that three peptides, SmMLCaa31-60, SmMLCaa61-90, and SmMLCaa46-76, significantly bound to PZQ (P < 0.05). PZQ bound more strongly to SmMLCaa46-76. Other peptides of SmMLC, including a negative control protein, rSmGBF (a cutoff line is shown), did not bind to PZQ. OD, optical density.

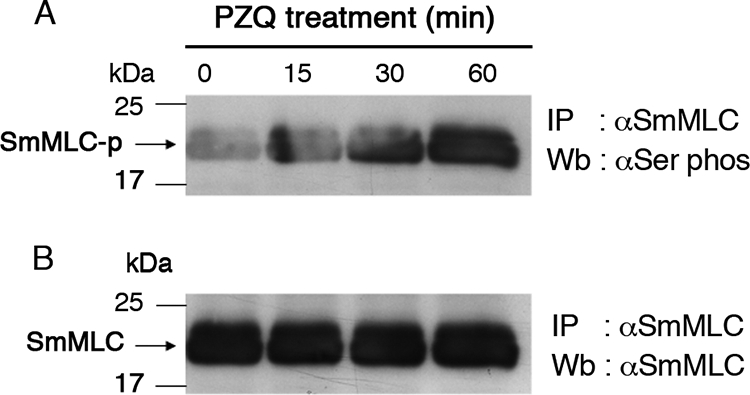

SmMLC is phosphorylated in vivo upon exposure to PZQ.

Native SmMLC was then immunoprecipitated from schistosomula that were exposed to PZQ. Evaluation of these SmMLCs showed that native SmMLC is phosphorylated upon exposure to PZQ. This phosphorylation seems to be time dependent and could be detected as early as 30 min after exposure to PZQ (Fig. 7A). PZQ treatment does not appear to alter the expression of SmMLC (Fig. 7B). At this time we do not know whether PZQ has any direct effect on host MLC.

FIG. 7.

PZQ upregulates phosphorylation of SmMLC. Schistosomula were incubated with 20 μg/ml of PZQ. SmMLC was immunoprecipitated (IP) from the worm homogenates by using mouse anti-SmMLC antibodies. The IP proteins were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with either anti-phosphoserine/threonine monoclonal antibodies (A) or mouse anti-SmMLC antibodies (B). Data presented are one of three similar results. Wb, Western blot.

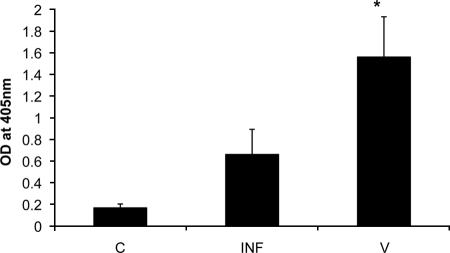

Anti-SmMLC antibodies are abundantly present in the vaccinated mice.

In addition to raising antibodies to rSmMLC in mice, we also tested the antibody levels to SmMLC in infected and vaccinated mice. ELISA results showed that vaccinated mice had significantly high levels of anti-SmMLC antibodies (P < 0.05) compared to levels in preimmune or infected mice (Fig. 8). These results suggest that SmMLC may be a potential target for protective immunity.

FIG. 8.

Antibodies against SmMLC in infected and vaccinated mice. Anti-SmMLC antibodies in the sera of mice infected 42 days previously (INF) with 150 cercariae or vaccinated (V) with 250 γ-irradiation-attenuated cercariae were determined using an ELISA. Preinfection/vaccination sera (C) were used as controls. Data presented are means ± standard deviations of five mice from each group of three similar experiments. OD, optical density.

DISCUSSION

PZQ is an effective and safe broad-spectrum, antiparasitic agent excellent for mass chemotherapy against schistosomiasis (8). The mechanism of action of this drug involves increasing calcium influx in the musculature of the parasite with resultant muscle contraction. Our results indicate that one of the mechanisms of action of PZQ may be through affecting of the function of SmMLC in the parasite.

In this study, we combined the phage display technology with labeled PZQ to identify the regulatory MLC as the major binding partner for PZQ. Myosin is a highly conserved, ubiquitous protein found in all eukaryotic cells, where it provides the motor function for diverse movements such as cytokinesis, phagocytosis, and muscle contraction (24). Structural analysis of myosin reveals that it contains two major domains, an amino-terminal motor/head domain and a carboxy-terminal tail domain. Based on the properties of these head domains, seven distinct classes of myosin have been described to date. Among these, the class II myosins are the conventional two-headed myosins that form filaments and are composed of two myosin heavy-chain subunits and four MLC subunits (27). The regulatory MLC is a regulatory subunit of the class II myosin and plays a major role in the physiology of the parasite inside the host. In fact, myosin appears to be the most prominent cercarial polypeptide, synthesized three days before its emergence from the snail (3). Myosin is also believed to be critical for the migration of the parasite through the skin, because vigorous muscular movement is necessary for the penetration and tissue migration of the parasite through the skin. In fact, a homologue of the S. mansoni myosin fragment IrV-5 has been previously identified as a potential vaccine candidate (34). Our present study also shows highly elevated anti-SmMLC antibodies in the sera of mice vaccinated with irradiated cercariae. Thus, MLC may be a critical protein for survival of the parasite in the host. Since PZQ binds to SmMLC and affects its function, we propose that PZQ might be exerting its antiparasitic effects through SmMLC.

The complete cDNA sequence of the myosin heavy chain of S. mansoni is known (30). Our sequence analyses of the phage clone suggest that the myosin that bound to PZQ is regulatory MLC. Although not published, the full-length (GenBank accession no. AAA29873, AF071011, and L00992) or partial-length (accession no. T14468 and AA233982) sequences of S. mansoni MLC are also deposited in GenBank. A multiple alignment comparison of the various sequences reported or deposited in GenBank suggests that SmMLC has significant homology to calcium binding proteins.

MLCs in general are Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent proteins (21). Phosphorylation of MLC by MLC kinases increases the actin-activated myosin ATPase activity in the muscle cells and is thought to play major roles in a number of biological processes, including smooth muscle contraction and the organization and function of the contractile machinery during cytokinesis (24). Phosphorylation of MLC is also associated with an increase in Ca mobilization (33). Previous studies demonstrated that calcium influx into schistosome worms is a major event associated with the effect of PZQ (2). Thus, phosphorylation of MLC may be a major event in PZQ action. Results from our studies suggest that PZQ can directly bind to SmMLC and trigger its phosphorylation.

Another clone that bound to PZQ was actin. Schistosome actin has been proposed as the PZQ receptor by Tallima and El Ridi (25) based on binding to PZQ using an affinity column. This finding was challenged by Troiani et al. (26), who failed to repeat the finding by Tallima and El Ridi. Our findings are supportive of the report by Tallima and El Ridi, who also found actin binds to PZQ. In our study, we also found actin as the other clone that bound to PZQ. However, the significance of the PZQ binding to actin needs to be further characterized.

Although PZQ-resistant parasites are not a major threat in the areas where schistosomiasis is endemic at this time, several studies suggest that schistosomes subjected to drug pressure can develop resistance to PZQ (7), probably due to a genetically dominant trait (17), and such resistant parasites are less susceptible to the PZQ-induced tegumental damage in vitro (32). Our studies confirm that PZQ can affect the MLC function in S. mansoni parasites by triggering its phosphorylation. It will be interesting to see whether genetic polymorphism in SmMLC has any role in drug resistance against PZQ. Specifically, our studies identified the PZQ binding site of SmMLC within aa 46 to 76 of SmMLC. Further studies will characterize the peptide at aa 46 to 78 and evaluate its role in SmMLC function and parasite survival in the host.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by RO1 NIH grants AI-39066 and AI 64745 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews, P. 1985. Praziquantel: mechanisms of anti-schistosomal activity. Pharmacol. Ther. 29:129-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angelucci, F., A. Basso, A. Bellelli, M. Brunori, L. Pica Mattoccia, and C. Valle. 2007. The anti-schistosomal drug praziquantel is an adenosine antagonist. Parasitology 134:1215-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson, K. H., and B. G. Atkinson. 1981. Protein synthesis in vivo by Schistosoma mansoni cercariae. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 4:205-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Awadalla, H. N., M. Z. el Azzouni, A. I. Khalil, and S. T. el Mansoury. 1991. Scanning electron microscopy of normal and praziquantel treated S. haematobium worms (Egyptian strain). J. Egypt Soc. Parasitol. 21:715-722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blair, K. L., J. L. Bennett, and R. A. Pax. 1992. Praziquantel: physiological evidence for its site(s) of action in magnesium-paralysed Schistosoma mansoni. Parasitology 104:59-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crameri, R., R. Jaussi, G. Menz, and K. Blaser. 1994. Display of expression products of cDNA libraries on phage surfaces. A versatile screening system for selective isolation of genes by specific gene-product/ligand interaction. Eur. J. Biochem. 226:53-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doenhoff, M. J., J. R. Kusel, G. C. Coles, and D. Cioli. 2002. Resistance of Schistosoma mansoni to praziquantel: is there a problem? Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 96:465-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doenhoff, M. J., and L. Pica-Mattoccia. 2006. Praziquantel for the treatment of schistosomiasis: its use for control in areas with endemic disease and prospects for drug resistance. Exp. Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 4:199-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Bassiouni, E. A., M. H. Helmy, E. I. Saad, M. A. El-Nabi Kamel, E. Abdel-Meguid, and H. S. Hussein. 2007. Modulation of the antioxidant defence in different developmental stages of Schistosoma mansoni by praziquantel and artemether. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 64:168-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fetterer, R. H., R. A. Pax, and J. L. Bennett. 1980. Praziquantel, potassium and 2,4-dinitrophenol: analysis of their action on the musculature of Schistosoma mansoni. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 64:31-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gnanasekar, M., K. V. Rao, Y. X. He, P. K. Mishra, T. B. Nutman, P. Kaliraj, and K. Ramaswamy. 2004. Novel phage display-based subtractive screening to identify vaccine candidates of Brugia malayi. Infect. Immun. 72:4707-4715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenberg, R. M. 2005. Are Ca2+ channels targets of praziquantel action? Int. J. Parasitol. 35:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall, T. M., G. T. Joseph, and M. Strand. 1995. Schistosoma mansoni: molecular cloning and sequencing of the 200-kDa chemotherapeutic target antigen. Exp. Parasitol. 80:242-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Homeida, M. A., I. el Tom, T. Nash, and J. L. Bennett. 1991. Association of the therapeutic activity of praziquantel with the reversal of Symmers' fibrosis induced by Schistosoma mansoni. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 45:360-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu, W. Y., Y. J. Han, L. Z. Gu, M. Piano, and P. de Lanerolle. 2007. Involvement of ras-regulated Myosin light chain phosphorylation in the captopril effects in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am. J. Hypertens. 20:53-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hypolite, J. A., M. E. DiSanto, A. J. Wein, and S. Chacko. 1999. Myosin light chain phosphorylation at resting level and the composition of myosin isoforms in the bladder body and urethra. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. Suppl. 201:46-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang, Y. S., J. R. Dai, Y. C. Zhu, G. C. Coles, and M. J. Doenhoff. 2003. Genetic analysis of praziquantel resistance in Schistosoma mansoni. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 34:274-280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitsui, Y., and K. Arizono. 2001. A direct competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for determination of praziquantel concentration in serum. Int. J. Parasitol. 31:87-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morcos, S. H., M. T. Khayyal, M. M. Mansour, S. Saleh, E. A. Ishak, N. I. Girgis, and M. A. Dunn. 1985. Reversal of hepatic fibrosis after praziquantel therapy of murine schistosomiasis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 34:314-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Omar, A., S. Elmesallamy Gel, and S. Eassa. 2005. Comparative study of the hepatotoxic, genotoxic and carcinogenic effects of praziquantel distocide & the natural myrrh extract Mirazid on adult male albino rats. J. Egypt Soc. Parasitol. 35:313-329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfitzer, G. 2001. Invited review: regulation of myosin phosphorylation in smooth muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 91:497-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pica-Mattoccia, L., T. Orsini, A. Basso, A. Festucci, P. Liberti, A. Guidi, A. L. Marcatto-Maggi, S. Nobre-Santana, A. R. Troiani, D. Cioli, and C. Valle. 2008. Schistosoma mansoni: lack of correlation between praziquantel-induced intra-worm calcium influx and parasite death. Exp. Parasitol. 119:332-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao, K. V., L. Chen, M. Gnanasekar, and K. Ramaswamy. 2002. Cloning and characterization of a calcium-binding, histamine-releasing protein from Schistosoma mansoni. J. Biol. Chem. 277:31207-31213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Satterwhite, L. L., and T. D. Pollard. 1992. Cytokinesis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 4:43-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tallima, H., and R. El Ridi. 2007. Praziquantel binds Schistosoma mansoni adult worm actin. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 29:570-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Troiani, A. R., L. Pica-Mattoccia, C. Valle, D. Cioli, G. Mignogna, F. Ronketti, and M. Todd. 2007. Is actin the praziquantel receptor? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30:280-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trybus, K. M. 1994. Role of myosin light chains. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 15:587-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vennervald, B. J., M. Booth, A. E. Butterworth, H. C. Kariuki, H. Kadzo, E. Ireri, C. Amaganga, G. Kimani, L. Kenty, J. Mwatha, J. H. Ouma, and D. W. Dunne. 2005. Regression of hepatosplenomegaly in Kenyan school-aged children after praziquantel treatment and three years of greatly reduced exposure to Schistosoma mansoni. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 99:150-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Webbe, G., C. James, G. S. Nelson, and R. F. Sturrock. 1981. The effect of praziquantel on Schistosoma haematobium, S. japonicum and S. mansoni in primates. Arzneimittelforschung 31:542-544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weston, D., J. Schmitz, W. M. Kemp, and W. Kunz. 1993. Cloning and sequencing of a complete myosin heavy chain cDNA from Schistosoma mansoni. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 58:161-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiest, P. M., Y. Li, G. R. Olds, and W. D. Bowen. 1992. Inhibition of phosphoinositide turnover by praziquantel in Schistosoma mansoni. J. Parasitol. 78:753-755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.William, S., S. Botros, M. Ismail, A. Farghally, T. A. Day, and J. L. Bennett. 2001. Praziquantel-induced tegumental damage in vitro is diminished in schistosomes derived from praziquantel-resistant infections. Parasitology 122:63-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang, Y., S. Moreland, and R. S. Moreland. 1994. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle contraction: myosin light chain phosphorylation dependent and independent pathways. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 72:1386-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang, Y., M. G. Taylor, and Q. D. Bickle. 1998. Schistosoma japonicum myosin: cloning, expression and vaccination studies with the homologue of the S. mansoni myosin fragment IrV-5. Parasite Immunol. 20:583-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]