Abstract

The genome sequence of Mycobacterium leprae revealed a single open reading frame, ML2088 (CYP164A1), encoding a putative full-length cytochrome P450 monooxygenase and 12 pseudogenes. We have identified a homolog of ML2088 in Mycobacterium smegmatis and report here the cloning, expression, purification, and azole-binding characteristics of this cytochrome P450 (CYP164A2). CYP164A2 is 1,245 bp long and encodes a protein of 414 amino acids and molecular mass of 45 kDa. CYP164A2 has 60% identity with Mycobacterium leprae CYP161A1 and 66 to 69% identity with eight other mycobacterial CYP164A1 homologs, with three identified highly conserved motifs. Recombinant CYP164A2 has the typical spectral characteristics of a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, predominantly in the ferric low-spin state. Unusually, the spin state was readily modulated by increasing ionic strength at pH 7.5, with 50% high-spin occupancy achieved with 0.14 M NaCl. CYP164A2 bound clotrimazole, econazole, and miconazole strongly (Kd, 1.2 to 2.5 μM); however, strong binding with itraconazole, ketoconazole, and voriconazole was only observed in the presence of 0.5 M NaCl. Fluconazole did not bind to CYP164A2 at pH 7.5 and no discernible type II binding spectrum was observed.

Leprosy has afflicted humanity through the ages and remains today a serious and disfiguring condition in communities throughout the developing world. Immunization (18) and multidrug treatment programs have been effective in reducing morbidity and mortality due to lepromatous leprosy, but the incidence of new infections, at 680,000 per annum (36), remains high. Genome sequencing projects have been completed for several mycobacterial species, including both Mycobacterium leprae, the etiologic agent of leprosy, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. A common objective of these schemes is to identify potential targets for the development of novel antimycobacterial compounds. Unusually for bacteria, the actinomycetes such as mycobacteria and streptomycetes contain substantial numbers of genes encoding cytochromes P450 (CYPs) or P450 pseudogenes (6, 23). These enzymes carry out a wide range of monooxygenation reactions involved in biocatalysis, secondary metabolism, and detoxification. CYPs are ubiquitous throughout the eukaryotes but are relatively uncommon in prokaryotes, with most prokaryotes containing no CYP genes. The unexpected discovery in M. tuberculosis of an ortholog of CYP51 (3), the sterol 14α-demethylase of eukaryotes (19), proved a major catalyst for investigations into the CYP complements (CYPomes) of mycobacteria, as CYP51 is the target for azole antifungal drugs that have been shown to possess antimycobacterial properties (1, 5, 15, 35).

Most azole antifungal compounds show selective targeting of CYP51, having an 8- to 128-fold-higher affinity for fungal CYP51s relative to the orthologous enzyme present in the host (29). These compounds act by inhibiting the fungal sterol biosynthesis pathway, which does not exist in mycobacteria. The abundance of P450 proteins in mycobacterial species has raised the possibility that azoles could have either a specific or general inhibitory activity against mycobacteria through inhibition of CYP activity, even if the current azole antifungals are not effective. Several recent publications have supported the validity of this hypothesis (1, 5, 14, 16, 35). Ketoconazole, when used in conjunction with isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and rifampin, significantly improved the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis in mice in comparison to using the same drug regimen minus ketoconazole (5). Orally administered econazole used in combination with moxifloxacin and rifampin was effective in totally clearing tuberculosis from the organs of mice after 8 weeks (1). Recently, 4,4′-dihydroxybenzophenone (DHBP) has been cocrystallized with CYP51 from M. tuberculosis (11). Treatment with 100 μM DHBP reduced the number of M. tuberculosis CFU isolated from mouse macrophage cells by 40 to 70%.

M. leprae has one CYP gene, ML2088, encoding a P450; this represented the first member of the CYP164 cytochrome P450 family and was named CYP164A1 (http://drnelson.utmem.edu/CytochromeP450.html) (7). In common with many other genes, numerous cytochromes P450 have been lost recently from the genome and have been associated with evolution toward a host-dependent life cycle. Pseudogenes with homology to 10 of the 20 M. tuberculosis CYP genes, as well as for 2 without homology to M. tuberculosis CYP genes, are also present. Interestingly, there is no leprosy pseudogene corresponding to a lost CYP51. The characterization of the ML2088 CYP of M. leprae presents difficulties, as this bacterium cannot be cultured in vitro. Standard approaches to express ML2088 as a heterologous protein in Escherichia coli using pET vectors failed to yield correctly folded protein, as indicated by a reduced carbon monoxide difference spectral peak for the hemoprotein around 450 nm (unpublished observation). However, studies in our laboratory on the CYPome of M. smegmatis (16, 19) uncovered a CYP (A0R5U2) with close identity to that encoded by ML2088. It was designated as CYP164A2, having greater than 55% amino acid identity with M. tuberculosis CYP164A1. We report here the isolation, characterization, and azole-binding properties of this novel mycobacterial CYP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification and cloning of an ML2088 homolog from M. smegmatis ATCC 700084.

The predicted protein translation of the leprosy P450 gene ML2088, encoding CYP164A1 (Q9CBE7), was used to perform a TBLASTN search of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) microbial genomes database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/Entrez/genom_table_cgi). The best alignment was produced with a translated product from M. smegmatis.

The P450 gene was amplified from genomic DNA of M. smegmatis strain ATCC 700084. The forward primer MSLEPF (5′-AGCTCATATGCACAATGGGTGGAT-3′) and reverse primer MSLEPHIS (5′-GCATAAGCTTTCAATGGTGATGGTGTACCGCGATGGATAACG-3′) (MWG-Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany) were constructed to amplify the 1,245-bp P450 gene. MSLEPF was designed from residues 841237 to 841254 and MSLEPHIS from the reverse complement of residues 842464 to 842481 of contig 3312 from the M. smegmatis genome sequencing project. The primers incorporated NdeI and HindIII restriction sites (underlined) to facilitate subcloning into the Novagen expression vector pET17b. The stop codon was removed from the reverse primer MSLEPHIS, and four histidine codons (italics) followed by a new stop codon were inserted after the 3′ end of the downstream coding sequence for ease of purification of the recombinant protein.

Bioinformatic analyses.

A BLASTP search was performed using the CYP164A2 amino acid sequence against both the UniProtKB/TrEMBL and NCBI databases. This search identified eight mycobacterial CYP proteins that were closely related to M. smegmatis CYP164A2. A BLASTP search of the M. marinum genome project database (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_marinum/) identified one CYP164A2-like protein. These nine CYP proteins were M. leprae CYP (accession number Q9CBE7), M. gilvum (accession number A4T681), Mycobacterium sp. strain JLS (accession number A3Q7G4), Mycobacterium sp. strain MCS (accession number Q1B233), Mycobacterium sp. strain KMS (accession number A1UN16), M. vanbaalenii (accession number A1TGP4), M. paratuberculosis (accession number Q744J7), M. avium (accession number A0Q9Q7), and M. marinum (MM5268). The online BLOCKMAKER program (http://blocks.fhcrc.org/blocks/make_blocks.html) was used to identify conserved ungapped MOTIF segments between the 10 mycobacterial CYP proteins. Sequence identities were determined using the online BLAST2 sequence comparison tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/bl2seq/wblast2.cgi).

Heterologous expression in E. coli and isolation of recombinant CYP51 and CYP164A2 proteins.

The CYP51-pET17b and CYP164A2-pET17b constructs were transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3).pLys by using ampicillin selection. M. smegmatis CYP51-pET17b (16) was used as a control to allow a comparison of the azole-binding properties. Overnight cultures (10 ml) of transformants were used to inoculate 1-liter volumes of Terrific Broth supplemented with 20 g liter−1 peptone and 0.1 mg ml−1 sodium ampicillin. Cultures were grown at 37°C, 230 rpm, for 6 h prior to induction with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and expression at 25°C, 190 rpm for 18 h in the presence of 1 mM 5-aminolevulenic acid. Recombinant CYP51 and CYP164A2 proteins were isolated according to the method of Arase et al. (2) except that 2% (wt/vol) sodium cholate and no Tween 20 were used in the sonication buffer. The solubilized CYP51 and CYP164A2 proteins were purified by affinity chromatography using Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) agarose as previously described (3) with the modification that 0.1% (wt/vol) l-histidine in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, and 25% (wt/vol) glycerol were used to elute nonspecifically bound E. coli proteins after the salt washes and elution of P450 protein was achieved with 1% (wt/vol) l-histidine in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, and 25% (wt/vol) glycerol. Protein purity was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (20) and specific P450 content.

Determination of cytochrome P450 protein concentrations.

Cytochrome P450 concentrations were determined by reduced carbon monoxide difference spectra according to the methods of Estabrook et al. (12). An extinction coefficient of 91 mM−1 cm−1 (27) was used to calculate P450 concentrations. Absolute spectra for both M. smegmatis CYP51 and CYP164A2 were determined as previously described (3) in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, and 25% (wt/vol) glycerol (binding buffer). The oxidized spectra of both proteins were determined in the presence of 0, 0.5 M, and 4 M NaCl in binding buffer. The low-spin state spectra of CYP164A2 and CYP51 were determined in 60% (vol/vol) ethylene glycol in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.2. Calculation of the low-spin fraction was performed as previously described (25). All spectral determinations were made using a Hitachi U-3310 UV/VIS spectrophotometer (San Jose, CA) with Ni2+-NTA-agarose-purified CYP51 (2.44 μM) and CYP164A2 (2.62 μM) proteins. Protein concentrations were determined by the Coomassie blue R250 dye-binding method (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom) using bovine serum albumin standards.

Azole-binding spectral determinations.

Binding assays of azole antifungal agents to CYP51 and CYP164A2 were performed as previously described (21, 22) using split cuvettes, except that dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was also added to the cytochrome P450-containing compartment of the reference cuvette. Stock 0.5-mg ml−1 solutions of clotrimazole, econazole, fluconazole, itraconazole, ketoconazole, miconazole, and voriconazole were prepared in DMSO. Azole was progressively titrated against Ni2+-NTA-agarose-purified CYP51 (2.44 μM) and CYP164A2 (2.62 μM) to a maximum DMSO concentration of 2.5% (vol/vol), with the spectral difference determined after each incremental addition of azole. All spectral determinations were performed in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, and 25% (wt/vol) glycerol, in both the presence and absence of 0.5 M NaCl. Voriconazole binding to CYP164A2 was investigated at several NaCl concentrations from 0 to 2 M. In addition, the binding of clotrimazole to CYP51 and CYP164A2 was determined in the presence of 0.1% (wt/vol) Triton X-100. The dissociation constant (Kd) of the enzyme-azole complex for each azole was determined by nonlinear regression (Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm) of the ΔApeak-trough against the azole concentration, using the Hill equation [ΔA = ΔAmax/(1 + Kd/[azole]n)] (28) and the Michaelis-Menten-Henri equation, ΔA = (ΔAmax[azole])/(Kd + [azole]), where allosterism was not observed.

Data analysis.

Analyses of the DNA and protein sequences were performed using the computer programs Chromas version 1.45 (http://www.technelysium.com.au/chromas14x.html), ClustalX version 1.8 (ftp://ftp-igbmc.u-strasbg.fr/pub/), and BioEdit version 5.0.6. (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html). Curve-fitting of data was performed using ProFit 5.01 (QuantumSoft, Zurich, Switzerland).

Chemicals.

All chemicals, including azole antifungals except for voriconazole, were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company (Poole, United Kingdom). Voriconazole was supplied by Discovery Fine Chemicals (Bournemouth, United Kingdom). Difco growth media were obtained from Becton Dickinson Ltd. (Cowley, United Kingdom).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The MSLEP DNA and protein sequences have been deposited in the UniProKM/TREMBL database as accession number A0R5U2. We encountered CYP naming anomalies: the A0R5U2 entry described the protein as a CYP107B1. However, a second CYP107B1 protein has also been deposited in the UniProKM/TREMBL database for M. smegmatis strain ATCC 700084 (accession number A0QX10), which shares only 34% identity with A0R5U2. Therefore, the more appropriate name for A0R5U2 is CYP164A2, as originally assigned, because it shares 60% identity with M. leprae CYP164A1 (accession number Q9CBE7).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Bioinformatic analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis of M. smegmatis CYP164A2 (accession number A0R5U2) against nine other closely related mycobacterial CYPs (CYP164A1 homologs) indicated that CYP164A2 had greatest homology toward M. gilvum (accession number A4T681) with 69% identity, followed by Mycobacterium sp. strain JLS (A3Q7G4), Mycobacterium sp. strain MCS (Q1B233), Mycobacterium sp. strain KMS (A1UN16), and M. vanbaalenii (A1TGP4), with 68% identity. M. smegmatis CYP164A2 shared 67% identity with both M. paratuberculosis (Q744J7) and M. avium (A0Q9Q7), along with 66% identity with M. marinum (MM5268). M. smegmatis CYP164A2 shared 60% identity (249/415) and 75% similarity (313/415) with M. leprae CYP164A1 (ML2088) in a 415-amino-acid overlap (BLASTP score, e-130). Homology extended across all regions of the proteins, with only two introduced gaps. In contrast, the closest M. tuberculosis homolog was CYP140; this gave only 38% identity (145/379) and 51% similarity (196/397) in a 397-bp overlap, with 30 introduced gaps (BLASTP score, 3e-58). Regions of homology occurred in sequences containing conserved P450 motifs, such as the heme-binding domain. CYP164A2 shared only 24% identity with M. smegmatis CYP51 and 23% identity with M. tuberculosis CYP51. The closely related Streptomyces avermitilis CYP107P2 (Q82ES4) shared 39% identity with M. smegmatis CYP164A2, and Saccharopolyspora erythraea CYP107A1 (P450eryF-Q00441) shared 36% identity with CYP164A2.

The M. smegmatis CYP164A2 gene is 1,245 bp in length and encodes a protein that is 414 amino acids long and has a molecular mass of 45.0 kDa and theoretical pI of 5.09, in comparison to M. leprae CYP164A1 (Q9CBE7), which is 1,305 bp long, encodes a protein of 415 amino acids in length and 47.2 kDa molecular mass, and has a theoretical pI of 5.16. The other mycobacterial CYP164A1 homologs were 405 to 442 amino acids in length with predicted molecular masses of 43.5 to 48.7 kDa and predicated pI values of 4.8 to 5.2. M. smegmatis CYP164A2 and M. smegmatis CYP51, in common with most bacterial CYPs, contain no identifiable N-terminal signal or membrane anchor sequences and are expressed in the cytosol, unlike fungal CYPs, which contain a membrane anchor sequence and are located in the endoplasmic reticulum.

A comparison of the CYP164A1 homologs using the BLOCKMAKER program identified eight conserved MOTIF regions (Table 1). Blocks A, C, and E are highly conserved, with 65, 52, and 67%, respectively, of the amino acid residues conserved among all 10 mycobacterial species. Blocks B, G, and H are moderately conserved (46, 47, and 41%, respectively), and blocks D and F are poorly conserved (37 and 24% conserved). Block G contained the cysteine residue that forms the fifth ligand of the heme prosthetic group and the main C-terminal heme-binding domain. The high degree of conservation in the conserved motifs identified (Table 1), especially in blocks A, C, and E, suggests a possible role in defining the substrate access channel and substrate-binding pocket for the mycobacterial CYP164A1 homologs.

TABLE 1.

Identification of conserved regions in mycobacterial CYP164A1 homologsa

| Block | No. of residues | Block consensus sequence |

|---|---|---|

| A | 55 | 26 ANRADPYPLYAXFRXXGPLQLPEANLXVFSXFXDCDEVLRHPXSXSDRXKSTVAQ |

| B | 52 | 84 AAGAXPRPFGPPGFLFLDPPDHTRLRRLVSKAFVPRVIKALEPEIVSLVDXL |

| C | 33 | 142 GEFDXIXDLAYPLPVAVICRLLGVPLEDEPQFS |

| D | 35 | 201 RXXAGXWLRDYLRELIXXRRXXPGDDLXSGLIAVE |

| E | 39 | 241 LTEDEIVATCNLLLVAGHETTVNLIANAALAMLRXPGQW |

| F | 45 | 280 AALAADPXRAXAVXEETLRYDPPVQLVSRIAAXDMTIGGVTVPKG |

| G | 30 | 341 FDRPDTFDPDRXXLRHLGFGKGAHFCLGAP |

| H | 44 | 371 LARLEAXVALSAVTARFPXARLAGEPVYKPNVTLRGMSXLSVAX |

The online program BLOCKMAKER (http://blocks.fhcrc.org/blocks/make_blocks.html) was used to identify conserved ungapped MOTIF regions of amino acid residues between M. smegmatis CYP164A2 and nine CYP164A1 homologs from different mycobacterial species. The mycobacterial CYPs compared were M. smegmatis CYP164A2 (accession number A0R5U2), M. leprae CYP (Q9CBE7), M. gilvum (A4T681), Mycobacterium sp. strain JLS (A3Q7G4), Mycobacterium sp. strain MCS (Q1B233), Mycobacterium sp. strain KMS (A1UN16), M. vanbaalenii (A1TGP4), M. paratuberculosis (Q744J7), M. avium (A0Q9Q7), and M. marinum (MM5268). Amino acid residues conserved between all 10 sequences are underlined. Nonconserved amino acid residues, present in 4 or fewer of the 10 CYP proteins, are represented by the letter X. The residue numbers of each block relate to the start position in the M. smegmatis CYP164A2 protein.

Heterologous expression and purification of recombinant CYP51 and CYP164A2 proteins.

Both M. smegmatis CYP51 and CYP164A2 proteins were expressed in E. coli. Protein isolation by cholate extraction using sonication (2) gave yields of 1.5 and 0.6 μmol per liter of culture for CYP51 and CYP164A2, respectively. Purification by Ni2+-NTA-agarose affinity chromatography gave 4.1- and 16.8-fold increases in purity for CYP51 and CYP164A2, respectively, with specific activities of 10.1 and 18.7 nmol mg−1 for CYP51 and CYP164A2 based on the reduced CO-P450 assay of Estabrook et al. (12).

The purities of Ni2+-NTA-agarose-purified CYP51 and CYP164A2 were determined to be 63% and 79%, respectively, using the UTHSCSA ImageTool 3.0 (http://ddsdx.uthscsa.edu/dig/itdesc.html) to analyze pixel gray-scale density and coverage area of the stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. This compared with purities of 57% and 84% for CYP51 and CYP164A2 obtained from CO-P450 difference spectra and protein determinations using the Bio-Rad Coomassie blue dye-binding assay. Apparent molecular masses of 50.2 and 44.7 kDa were obtained for CYP51 and CYP164A2, which were close to the predicted values of 51,563 and 44,955 Da.

Spectral properties of recombinant CYP51 and CYP164A2 proteins.

Absolute spectra (Fig. 1A and B) and reduced CO-P450 difference spectra (Fig. 1C) of M. smegmatis CYP51 and CYP164A2 were characteristic of a cytochrome P450 enzyme (3, 17), indicating that both enzymes were expressed in their native form. CYP51 displayed the typical spectral properties of a ferric P450 with a low-spin-state heme iron Soret γ band at 418 nm in addition to α, β, and δ bands at 570, 535, and 355 nm, respectively. CYP164A2 gave a similar absolute spectrum in the oxidized low-spin ferric form with a Soret γ band at 415 nm in addition to α, β, and δ bands at 566, 534, and 358 nm, respectively. The δ band of CYP164A2 was just distinguishable as a shoulder on the leading edge of the γ band. Dithionite one-electron reduction caused a small blue shift of the Soret γ band from 418 to 416 nm and from 415 to 412 nm for CYP51 and CYP164A2, respectively, and the α and β bands to merge with absorption maxima at 549 and 545 nm for CYP51 and CYP164A2, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Absolute and reduced carbon monoxide difference spectra. Absolute spectra of M. smegmatis CYP51 (A) and CYP164A2 (B) were determined for the oxidized form (line 1), dithionite reduced form (line 2), and reduced carbon monoxide form (line 3). (C) Reduced carbon monoxide difference spectra were determined independently using M. smegmatis CYP51 (solid line) and CYP164A2 (dashed line) as previously described by Estabrook et al. (12) and an extinction coefficient of 91 mM−1 cm−1 at 448 nm (27). All spectral determinations were made using Ni2+-NTA-agarose-purified CYP51 (0.244 mg of protein ml−1) and CYP164A2 (0.140 mg of protein ml−1).

Binding carbon monoxide to dithionite-reduced ferrous P450 resulted in a typical red shift of the Soret γ band from 416 to 448 nm and from 412 to 448 nm for CYP51 and CYP164A2, respectively, in the formation of the CO-ferrous P450 complex. For M. smegmatis CYP51, a significant amount of P420 was also formed when carbon monoxide bound, suggesting instability in the presence of dithionite. The carbon monoxide difference spectra obtained (Fig. 1C) showed no significant P420 present when dithionite was added last just prior to recording the absorbance spectrum.

The spin state of M. smegmatis CYP164A2 was highly sensitive to NaCl concentration at pH 7.5 (Fig. 2). In the absence of NaCl, nearly 75% of CYP164A2 molecules occupied the low spin state (25% high spin), as calculated using the method of Lange et al. (25). The addition of 0.5 M and 4 M NaCl caused 86% and 100% of the CYP164A2 molecules to occupy the high spin state. The low spin to high spin state transition of CYP164A2 was characterized by the blue shift of the γ Soret band from 417 to 393 nm. The calculated 50% high-spin occupancy point for CYP164A2 was 0.14 M NaCl in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, and 25% (wt/vol) glycerol. The spin state of M. smegmatis CYP51, in contrast, was relatively insensitive to NaCl concentration at pH 7.5. In the absence of NaCl, 94% of the CYP51 molecules occupied the low spin state (6% high spin), with the addition of 0.5 M and 4 M NaCl only causing 12% and 23% occupancy of the high spin state, respectively. The complete modulation of CYP164A2 spin state by ionic strength, especially in the absence of substrate, is a rare phenomenon among cytochrome P450 enzymes. The resting state of most cytochrome P450s is predominantly the low-spin ferric state (34), where water is coordinated to the heme prosthetic group as the sixth ligand. Displacement of water as the sixth ligand, for example by substrate, induces a change in spin state from low to high spin, suggesting that increasing ionic strength, either directly or indirectly, causes the progressive dissociation of water as the sixth ligand of the heme moiety in CYP164A2. Previous studies investigating the effects of ionic strength on the CYP spin state have used subzero temperatures, various pHs, presence of cosolvents, presence of substrates, and elevated pressures (8, 9, 10, 13, 24, 25, 31, 32, 37, 38), due to the relative insensitivities of the spin states of many CYPs to modulation by ionic strength in the absence of substrate. We are currently performing further investigations on the modulation of CYP164A2 spin state by ionic strength.

FIG. 2.

Modulation of CYP164A2 spin state by NaCl. The 100% low spin state of CYP164A2 (line 1) was obtained in the presence of 60% (vol/vol) ethylene glycol, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.2. The absolute spectrum of CYP164A2 was determined at pH 7.5 in the absence of NaCl (line 2) and in the presence of 0.5 M NaCl (line 3) and 4 M NaCl (line 4). The γ-Soret peak region (310 to 460 nm) of the spectrum has been expanded to clearly show the change in spin state from low spin (417 nm) to high spin (393 nm) caused by the increasing NaCl concentration.

Azole-binding studies.

Binding of azole antifungal agents (Table 2 and Fig. 3) identified several differences between M. smegmatis CYP51 and CYP164A2. Type II azole-binding spectra were obtained as a result of the imidazole ring nitrogen coordinating as the sixth ligand with the heme iron. Absorbance maxima were similar for both CYPs (429 to 433 nm); however, the absorbance minima differed between CYP51 (409 to 412 nm) and CYP164A2 (392 to 395 nm).

TABLE 2.

Binding constants of M. smegmatis CYP51 and CYP164A2 for azole antifungalsa

| Azole and additional agent(s) | CYP51

|

CYP164A2

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd (μM) | nHapp | ΔAmaxb | Kd (μM) | nHapp | ΔAmaxb | |

| Clotrimazole | 0.62 ± 0.03 | 2.20 ± 0.10 | 0.0679 | 1.20 ± 0.09 | 1.68 ± 0.15 | 0.0579 |

| +0.5 M NaCl | 0.43 ± 0.09 | 1.80 ± 0.05 | 0.0741 | 2.66 ± 0.08 | 1.45 ± 0.03 | 0.1080 |

| +0.1% Tritonc | 3.06 ± 0.07 | 1.00 ± 0.01 | 0.1001 | 15.98 ± 0.49 | 1.02 ± 0.02 | 0.0499 |

| Econazole | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 1.80 ± 0.06 | 0.0737 | 2.52 ± 0.14 | 1.15 ± 0.07 | 0.0355 |

| +0.5 M NaCl | 1.66 ± 0.08 | 2.21 ± 0.08 | 0.0808 | 9.31 ± 0.15 | 1.00 ± 0.02 | 0.0879 |

| Fluconazole | 19.05 ± 1.52 | 1.18 ± 0.07 | 0.0229 | NDd | ND | ND |

| +0.5 M NaCl | 5.94 ± 0.27 | 1.36 ± 0.04 | 0.0496 | ND | ND | ND |

| Itraconazole | 1.26 ± 0.12 | 2.05 ± 0.20 | 0.0182 | 0.78 ± 0.45 | 1.00 ± 0.10 | 0.0024 |

| +0.5 M NaCl | 3.00 ± 0.38 | 2.51 ± 0.27 | 0.0235 | 1.11 ± 0.08 | 1.07 ± 0.12 | 0.0124 |

| Ketoconazole | 7.45 ± 0.11 | 1.26 ± 0.02 | 0.0742 | 5.69 ± 0.53 | 1.11 ± 0.11 | 0.0057 |

| +0.5 M NaCl | 4.59 ± 0.24 | 1.32 ± 0.06 | 0.0745 | 7.48 ± 0.24 | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 0.0427 |

| Miconazole | 1.16 ± 0.07 | 1.79 ± 0.07 | 0.0678 | 2.48 ± 0.12 | 1.17 ± 0.07 | 0.0355 |

| +0.5 M NaCl | 0.94 ± 0.02 | 2.55 ± 0.06 | 0.0710 | 5.57 ± 0.17 | 0.91 ± 0.04 | 0.0710 |

| Voriconazole | 5.94 ± 0.17 | 1.24 ± 0.02 | 0.0389 | 3.24 ± 0.68 | 1.14 ± 0.22 | 0.0052 |

| +0.5 M NaCl | 4.57 ± 0.07 | 1.32 ± 0.01 | 0.0422 | 19.72 ± 2.53 | 0.87 ± 0.10 | 0.0271 |

Azole antifungals were titrated against M. smegmatis CYP51 and CYP164A2 in order to construct azole saturation curves, from which Kd values were determined using nonlinear regression of the Hill equation, ΔA = ΔAmax/(1 + Kd/[azole]n). Titration was performed in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, and 25% (wt/vol) glycerol, with or without 0.5 M NaCl. Clotrimazole binding to CYP51 and CYP164A2 was also determined in the presence of 0.1% (wt/vol) Triton X-100. The values quoted in the table are those obtained from curve-fitting the mean values of three replicates followed by the standard deviations generated by the curve-fitting process.

Standard deviations for the ΔAmax values did not exceed 10% of the values quoted in the table and were typically 1 to 5% of the value quoted.

The detergent Triton X-100 was added.

ND, not determined, as no reproducible type II binding spectrum could be obtained for fluconazole with CYP164A2.

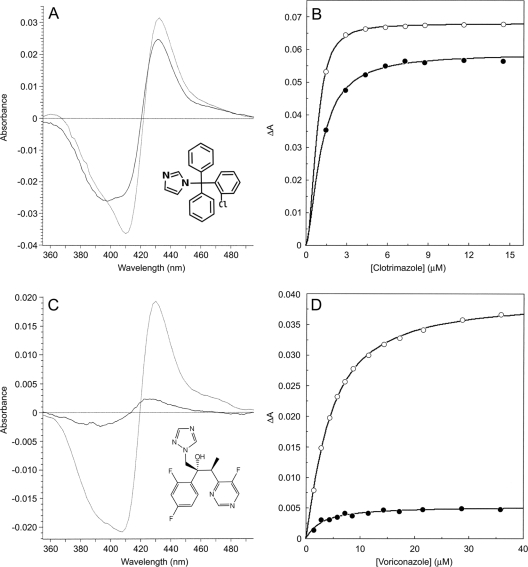

FIG. 3.

Spectral titration of clotrimazole and voriconazole against M. smegmatis CYP51 and CYP164A2. Azole was progressively titrated against Ni2+-NTA-agarose-purified CYP51 (2.44 μM) and CYP164A2 (2.62 μM) to a maximum DMSO concentration of 2.5% (vol/vol) with the spectral difference (ΔApeak-trough) determined after each incremental addition of azole. The type II binding spectra obtained using 4.4 μM clotrimazole (A) and 21.5 μM voriconazole (C) for both CYP51 (solid lines) and CYP164A2 (dashed lines) are shown as well as the saturation curves obtained using clotrimazole (B) and voriconazole (D) for CYP51 (hollow circles) and CYP164A2 (filled circles). Nonlinear regression (Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm) of the Hill equation, ΔA = ΔAmax/(1 + Kd/[azole]n) (28) was used to analyze the data.

Differences in azole-binding allosterism were observed, with strong positive cooperativity shown for the binding of clotrimazole, econazole, itraconazole, and miconazole (nH.app, 1.8 to 2.2) and mild positive cooperativity observed for fluconazole, ketoconazole, and voriconazole (nH.app, 1.2 to 1.3) with CYP51 (nH.app is the apparent Hill number as determined for the parameter ‘n’ by nonlinear regression of the Hill equation). However, strong positive cooperativity was only observed for CYP164A2 with clotrimazole (nH.app, 1.7) and no cooperativity was observed with the other azoles binding to CYP164A2 (nH.app, below 1.2). This suggests that the size of the substrate/azole-binding pocket and substrate access channel is relatively small compared to CYP51, preventing the binding of a second azole molecule.

Ouellet et al. (28) suggested two possible causes for the observed positive cooperativity of azole binding to CYPs. First, two or more specific azole-binding sites exist on the cytochrome P450 molecule, with positive cooperativity exerted between the binding sites (multiple site cooperativity) and with only one azole molecule directly coordinated as the sixth ligand of the heme prosthetic group and the other azole molecule acting as a positive allosteric effector/regulator. Secondly, cytochrome P450 molecules aggregate in vitro to form oligomers which then display positive cooperativity between the monomers during azole binding (multimer cooperativity). For M. tuberculosis CYP130 (28) the allosteric binding of econazole was due to protein-protein interactions, as the allosterism was disrupted by the addition of 50 mM KCl while 1:1 stoichiometry for bound azole was maintained. The addition of 0.5 M NaCl did not reduce the allosterism observed (Table 2) for azole binding with M. smegmatis CYP51 or the binding of clotrimazole to CYP164A2, suggesting that the allosterism observed was not due to electrostatic protein-protein interactions. The inclusion of the detergent Triton X-100 (Table 2) at 0.1% (wt/vol) during the binding of clotrimazole to CYP51 and CYP164A2 resulted in the elimination of the positive cooperativity previously observed, with the apparent Hill number falling to 1.0 and the Kd for clotrimazole increasing 5-fold for CYP51 and 13-fold for CYP164A2, indicating reduced affinity for the azole. Increasing the detergent concentration to 1% (wt/vol) caused further increases in the Kd and a progressive reduction in the ΔAmax (data not shown). Therefore, the allosterism observed for clotrimazole binding to CYP51 and CYP164A2 appears to be mediated by hydrophobic interactions between CYP monomers, which are disrupted by the inclusion of detergent. The increase in Kd for clotrimazole binding was probably due to detergent molecules adhering to hydrophobic regions of the CYP molecules, inhibiting clotrimazole access to the substrate/azole-binding pocket.

M. smegmatis CYP51 bound clotrimazole, econazole, and miconazole with a two- to threefold-higher affinity than CYP164A2 (Table 2), in contrast to itraconazole, ketoconazole, and voriconazole, for which CYP164A2 and CYP51 had similar affinities. CYP164A2-binding affinities for clotrimazole, econazole, and miconazole (Kd, 1.2 to 2.5 μM) were similar to those previously determined with M. tuberculosis CYP51 (Kd, 0.2 to 5 μM) (3, 16, 26, 28), M. smegmatis CYP51 (16), M. avium CYP51 (30), and M. tuberculosis CYP130 (28) with the exception of clotrimazole (Kd, 13.3 μM). The affinity of CYP164A2 for these three azoles was 17- to 84-fold less than for M. tuberculosis CYP121 (26).

No discernible type II binding spectra with fluconazole could be obtained using CYP164A2 in either the presence or absence of 0.5 M NaCl. Fluconazole only bound weakly to CYP51 (Kd, 19 μM). M. avium CYP51 (30) also bound fluconazole extremely weakly. The failure of CYP164A2 to bind fluconazole is probably not due to an inability to enter the substrate/azole-binding pocket, as larger azoles such as ketoconazole and itraconazole successfully bind to the CYP164A2 heme moiety. Therefore, it is likely that fluconazole is sterically hindered within the substrate/azole-binding pocket from obtaining a favorable conformation to coordinate with the heme moiety of CYP164A2 as the sixth ligand. Previous studies have demonstrated binding of fluconazole to M. tuberculosis CYP51, M. tuberculosis CYP121, and M. smegmatis CYP51, albeit with lower affinity (Kd, 6 to 23 μM) than other azole antifungals (3, 16, 26), while a Kd value of 70 μM was obtained for human CYP51 (4).

The CYP164A2-binding affinity for ketoconazole (Kd, 5.7 μM) was similar to those previously determined with M. tuberculosis CYP51 (3, 16, 26), M. smegmatis CYP51 (16), and M. tuberculosis CYP121 (26). However, CYP164A2 bound ketoconazole with twofold greater affinity than M. avium CYP51 (30), eightfold greater affinity than M. tuberculosis CYP130 (28), and threefold greater affinity than M. tuberculosis CYP51 as reported by Ouellet et al. (28). This compares with Kd values of 0.11 and 0.32 μM for ketoconazole obtained with human and bovine CYP51 (33), indicating ketoconazole would not be the azole of choice for intravenous treatment of mycobacterial infections. Voriconazole and itraconazole were found to bind poorly to M. avium CYP51 (30).

The intensity of the azole-binding spectra varied, with strong spectra (ΔAmax above 0.05) obtained with clotrimazole, econazole, ketoconazole, and miconazole for CYP51 and fluconazole, itraconazole, and voriconazole producing moderately strong spectra (ΔAmax above 0.02). In contrast, only clotrimazole gave strong azole-binding spectra with CYP164A2 in the absence of NaCl, econazole and miconazole gave moderately strong spectra, and itraconazole, ketoconazole, and voriconazole gave weak binding spectra (ΔAmax below 0.01) with CYP164A2.

The presence of 0.5 M NaCl had little effect on the azole-binding properties of CYP51, with the exception of fluconazole, where the observed ΔAmax increased by twofold and the Kd fell by threefold (Table 2). In contrast, 0.5 M NaCl had a dramatic effect on the azole-binding properties of CYP164A2, increasing the observed spectral binding intensity (ΔAmax) by 2- to 7.5-fold (especially itraconazole, ketoconazole, and voriconazole), accompanied by a 1.3- to 6-fold increase in the Kd value. This suggests the binding of azoles to the high-spin-state form of the heme moiety is favored over the low-spin form for CYP164A2 and for the binding of fluconazole to M. smegmatis CYP51. Increasing the ionic strength with 0.5 M NaCl caused a blue shift of the observed type II spectral maxima and minima with CYP164A2 by −6 nm for clotrimazole, econazole, miconazole, and voriconazole, −2 nm for itraconazole, and only −1 nm for ketoconazole. The observed blue shift was caused by the increased proportion of the high-spin-state form (86%) of CYP164A2 in the presence of 0.5 M NaCl (17). No corresponding blue shift was observed with M. smegmatis CYP51.

Voriconazole saturation studies with CYP164A2 (Table 3) indicated that increasing the ionic strength between 0 and 0.3 M NaCl increased the intensity of the observed type II binding spectra with a commensurate fourfold increase in the ΔAmax. However, increasing the NaCl concentration above 0.5 M resulted in a weakening of the intensity of the observed type II binding spectrum (reduction in ΔAmax), suggesting optimal voriconazole binding occurs between 0.3 and 0.5 M NaCl. However, the Kd initially increased 12-fold, reaching a maximum at 0.3 M NaCl and then decreasing at higher NaCl concentrations. This suggests that the affinity of CYP164A2 for voriconazole decreases with increasing NaCl concentration up to 0.3 M, above which affinity for voriconazole once again increases, even though the high ionic strength appears to no longer favor the formation of the [CYP164A2-voriconazole] complex, as observed by the decreasing ΔAmax values. Either NaCl concentrations above 0.5 M progressively alter the three-dimensional structure of CYP164A2 to restrict access to the substrate/azole-binding pocket or the high ionic strength increasingly dissociates the azole molecule from binding sites within the substrate/azole-binding pocket of the enzyme. Reduced solubility of azole antifungal drugs at high NaCl concentrations, especially for the larger hydrophobic azoles, could also be an important factor in the apparent reduced binding of azoles to CYP164A2 at high NaCl concentrations.

TABLE 3.

Effect of NaCl concentration on binding constants for voriconazole with CYP164A2a

| [NaCl]b (M) | Kd (μM) | ΔAmax |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.74 ± 0.47 | 0.0053 ± 0.0002 |

| 0.05 | 8.36 ± 0.62 | 0.0112 ± 0.0003 |

| 0.1 | 17.91 ± 2.79 | 0.0143 ± 0.0011 |

| 0.2 | 20.05 ± 3.77 | 0.0187 ± 0.0018 |

| 0.3 | 34.04 ± 9.66 | 0.0218 ± 0.0041 |

| 0.5 | 19.58 ± 2.07 | 0.0219 ± 0.0012 |

| 1.0 | 9.85 ± 2.99 | 0.0091 ± 0.0012 |

| 2.0 | 13.17 ± 1.37 | 0.0073 ± 0.0004 |

The binding constants Kd and ΔAmax were determined using the Michaelis-Menten-Henri equation. Fitting the data using the Hill equation gave nH app values between 0.8 and 1.2, indicating that the binding of voriconazole to CYP164A2 was not allosteric.

The NaCl concentration in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, and 25% (wt/vol) glycerol.

Mycobacterial species living within human tissues will be exposed to an external environment containing 0.15 M NaCl (0.09% [wt/vol] NaCl) and a cytosolic concentration unlikely to exceed this. At this concentration approximately half of the CYP164A2 molecules would exist in the high spin state, which appears to be the preferred spin state for azole binding in CYP164A2, leading to increased sensitivity of CYP164A2 to binding azole antifungal agents. Should azole drugs emerge as potential antileprosy therapies, then the variation seen here for CYP164A2 may assist in drug development considerations and also for other CYP targets in drug discovery and development. As with most microbial CYPs the function of CYP164 is unknown and its functional genomic investigation is an important area of future study, including gene deletion and metabolomic investigations. Some trials of azole compounds in treating M. leprae in model systems are also warranted.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Biotechnology and Biological Science Research Council of the United Kingdom for support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad, Z., R. Pandey, S. Sharma, and G. K. Khuller. 2008. Novel chemotherapy for tuberculosis: chemotherapeutic potential of econazole- and moxifloxacin-loaded PLG nanoparticles. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 31:142-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arase, M., M. R. Waterman, and N. Kagawa. 2006. Purification and characterization of bovine steroid 21-hydroxylase (P450c21) efficiently expressed in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 344:400-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellamine, A., A. T. Mangla, W. D. Nes, and M. R. Waterman. 1999. Characterisation and catalytic properties of the sterol 14α-demethylase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:8937-8942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellamine, A., G. I. Lepesheva, and M. R. Waterman. 2004. Fluconazole binding and sterol demethylation in three CYP51 isoforms indicate differences in active site topology. J. Lipid Res. 45:2000-2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrne, S. T., S. M. Denkin, P. Gu, E. Nuermberger, and Y. Zhang. 2007. Activity of ketoconazole against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vitro and in the mouse model. J. Med. Microbiol. 56:1047-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gas, C. E. Barry III, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, A. Krogh, J. McLean, S. Moule, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, J. Osborne, M. A. Quail, M.-A. Rajandream, J. Rodgers, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, J. Skelton, R. Squares, S. Squares, J. E. Sulston, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, B. G. Barrell, et al. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole, S. T., K. Eiglmeier, J. Parkhill, K. D. James, N. R. Thomson, P. R. Wheeler, N. Honore, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, K. Mungall, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. M. Davies, K. Devlin, S. Duthoy, T. Feltwell, A. Fraser, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, C. Lacroix, J. Maclean, S. Moule, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, M. A. Quail, M.-A. Rajandream, K. M. Rutherford, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, S. Simon, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Stevens, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, J. R. Woodward, and B. G. Barrell. 2001. Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature 409:1007-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davydov, D. R., A. E. Botchkareva, S. Kumar, Y. Q. He, and J. R. Halpert. 2004. An electrostatically driven conformational transition is involved in the mechanisms of substrate binding and cooperativity in cytochrome P450eryF. Biochemistry 43:6475-6485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deprez, E., N. C. Gerber, C. Di Primo, P. Douzou, S. G. Sligar, and G. Hui Bon Hoa. 1994. Electrostatic control of the substrate access channel in cytochrome P-450cam. Biochemistry 33:14464-14468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deprez, E., E. Gill, V. Helms, R. C. Wade, and G. Hui Bon Hoa. 2002. Specific and non-specific effects of potassium cations on substrate-protein interactions in cytochromes P450cam and P450lin. J. Inorg. Biochem. 91:597-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eddine, A. N., J. P. von Kries, M. V. Podust, T. Warrier, S. H. E. Kaufmann, and L. M. Podust. 2008. X-ray structure of 4,4′-dihydroxybenzophenone mimicking sterol substrate in the active site of sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51). J. Biol. Chem. 283:15152-15159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estabrook, R. W., J. A. Peterson, J. Baron, and A. G. Hildebrandt. 1972. The spectrophotometric measurement of turbid suspensions of cytochromes associated with drug metabolism, p. 303-350. In C. F. Chignell (ed.), Methods in pharmacology, vol. 2. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Funhoff, E. G., U. Bauer, I. Garcia-Rubio, B. Witholt, and J. B. van Beilen. 2006. CYP153A6, a soluble P450 oxygenase catalyzing terminal-alkane hydroxylation. J. Bacteriol. 188:5220-5227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guardiola-Diaz, H. B., L.-A. Foster, D. Mushrush, and A. D. N. Vaz. 2001. Azole-antifungal binding to a novel cytochrome P450 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: implications for treatment of tuberculosis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 61:1463-1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson, C. J., D. C. Lamb, D. E. Kelly, and S. L. Kelly. 2000. Bactericidal and inhibitory effects of azole antifungal compounds on Mycobacterium smegmatis. FEMS Lett. 192:159-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson, C. J., D. C. Lamb, T. H. Marczylo, J. E. Parker, N. L. Manning, D. E. Kelly, and S. L. Kelly. 2003. Conservation of CYP51 in mycobacteria; cloning and characterisation of sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) from Mycobacterium smegmatis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 301:558-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jefcoate, C. R. 1978. Measurement of substrate and inhibitor binding to microsomal cytochrome P-450 by optical-difference spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol. 52:258-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karonga Prevention Trial Group. 1996. Randomised controlled trial of single BCG, repeated BCG, or combined BCG and killed Mycobacterium leprae vaccine for prevention of leprosy and tuberculosis in Malawi. Lancet 348:17-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly, S. L., D. C. Lamb, C. J. Jackson, A. G. S. Warrilow, and D. E. Kelly. 2003. The biodiversity of microbial cytochromes P450. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 47:131-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamb, D. C., D. E. Kelly, W. H. Schunck, A. Z. Shyadehi, M. Akhtar, D. J. Lowe, B. C. Baldwin, and S. L. Kelly. 1997. The mutation T315A in Candida albicans sterol 14α-demethylase causes reduced enzyme activity and fluconazole resistance through reduced affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 272:5682-5688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamb, D. C., D. E. Kelly, K. Venkateswarlu, N. J. Manning, H. F. Bligh, W. H. Schunck, and S. L. Kelly. 1999. Generation of a complete, soluble, and catalytically active sterol 14 alpha-demethylase-reductase complex. Biochemistry 38:8733-8738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamb, D. C., T. Skaug, H. L. Song, C. J. Jackson, L. M. Podust, M. R. Waterman, D. B. Kell, D. E. Kelly, and S. L. Kelly. 2002. The cytochrome P450 complement (CYPome) of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Biol. Chem. 277:24000-24005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lange, R., G. Hui Bon Hoa, P. Debey, and I. C. Gunsalus. 1977. Ionization dependence of camphor binding and spin conversion of the complex between cytochrome P-450 and camphor: kinetic and static studies at sub-zero temperatures. Eur. J. Biochem. 77:479-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lange, R., C. Bonfils, and P. Debey. 1977. The low-spin ↔ high-spin transition of camphor-bound cytochrome P-450: effects of medium and temperature on equilibrium data. Eur. J. Biochem. 79:623-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLean, K. J., A. J. Warman, H. E. Seward, K. R. Marshall, H. M. Girvan, M. R. Cheesman, M. R. Waterman, and A. W. Munro. 2006. Biophysical characterization of the sterol demethylase P450 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, its cognate ferredoxin and their interactions. Biochemistry 45:8427-8443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omura, T., and R. Sato. 1964. The carbon monoxide-binding pigment of liver microsomes. J. Biol. Chem. 239:2379-2385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouellet, H., L. M. Podust, and P. R. Ortiz de Montellano. 2008. Mycobacterium tuberculosis CYP130: crystal structure, biophysical characterization, and interactions with antifungal azole drugs. J. Biol. Chem. 283:5069-5080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parker, J. E., M. Merkamm, N. J. Manning, D. Pompon, S. L. Kelly, and D. E. Kelly. 2008. Differential azole antifungal efficacy contrasted using a yeast strain humanized for sterol 14α-demthylase at the homologous locus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3597-3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pietila, M. P., P. K. Vohra, B. Sanyal, N. L. Wengenack, S. Raghavakaimal, and C. F. Thomas. 2006. Cloning and characterization of CCYP51 from Mycobacterium avium. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 35:236-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Renaud, J. P., D. R. Davydov, K. P. M. Heirwegh, D. Mansuy, and G. Hui Bon Hoa. 1996. Thermodynamic studies of substrate binding and spin transitions in human cytochrome P-450 3A4 expressed in yeast microsomes. Biochem. J. 319:675-681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulze, H., G. Hui Bon Hoa, V. Helms, R. C. Wade, and C. Jung. 1996. Structural changes in cytochrome P-450cam effected by the binding of the enantiomers (1R)-camphor and (1S)-camphor. Biochemistry 35:14127-14138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seliskar, M., R. Kosir, and D. Rozman. 2008. Expression of microsomal lanosterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) in an engineered soluble monomeric form. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 371:855-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sligar, S. G. 1976. Coupling of spin, substrate and redox equilibria in cytochrome P450. Biochemistry 15:5399-5406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Souter, A., K. J. McLean, W. E. Smith, and A. W. Munro. 2000. The genome sequence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals cytochromes P450 as novel anti-TB drug targets. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 75:933-941. [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. 2000. Leprosy—global situation. In WHO Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 75:226-231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yun, C. H., M. Song, T. Ahn, and H. Kim. 1996. Conformational change of cytochrome P450 1A2 induced by sodium chloride. J. Biol. Chem. 49:31312-31316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yun, C. H., T. Ahn, and F. P. Guengerich. 1998. Conformational change and activation of cytochrome P450 2B1 induced by salt and phospholipid. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 356:229-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]