Abstract

Background

Despite their potential benefits to patients with kidney cancer, the adoption of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy has been gradual and asymmetric. To clarify whether this trend reflects differences in kidney cancer patients or differences in surgeon practice styles, we compared the magnitude of surgeon-attributable variance in the use of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopic radical nephrectomy with that attributable to patient and tumor characteristics.

Methods

Using linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare data, we identified a cohort of 5,483 Medicare beneficiaries treated surgically for kidney cancer between 1997 and 2002. We defined two primary outcomes: (1) use of partial nephrectomy, and (2) use of laparoscopy among patients undergoing radical nephrectomy. Using multilevel models, we estimated surgeon- and patient-level contributions to observed variations in the use of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopic radical nephrectomy.

Results

Of the 5,483 cases identified, 611(11.1%) underwent partial nephrectomy (43 performed laparoscopically), and 4,872 (88.9%) underwent radical nephrectomy (515 performed laparoscopically). After adjusting for patient demographics, comorbidity, tumor size and surgeon volume, the surgeon-attributable variance was 18.1% for partial nephrectomy and 37.4% for laparoscopy. For both outcomes, the percentage of total variance attributable to surgeon factors was consistently higher than that attributable to patient characteristics.

Conclusions

For many patients with kidney cancer, the surgery provided depends more on their surgeon’s practice style than on the characteristics of the patient and his or her disease. Consequently, dismantling barriers to surgeon adoption of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy is an important step toward improving the quality of care for patients with early-stage kidney cancer.

Keywords: kidney cancer, renal cell carcinoma, surgery, partial nephrectomy, laparoscopy, technology adoption, practice patterns

Introduction

Open radical nephrectomy is the traditional gold standard for treating patients with organ-confined or locally-advanced renal cell carcinoma.1 During the last two decades, however, the concurrent introduction of nephron-sparing (i.e., partial nephrectomy) and minimally invasive (i.e., renal laparoscopy) alternatives to open radical excision have appreciably modified the therapeutic options.2-6

Easier convalescence7-10 and equivalent cancer control10 established laparoscopy as an alternative standard of care for most patients treated with radical nephrectomy.1,11 2,4,12 In synchronicity with the gradual dissemination of laparoscopic radical nephrectomy,2,4 multiple investigators reported that, for selected patients with smaller renal tumors, partial nephrectomy yields oncologic outcomes that are indistinguishable from those achieved by radical excision.13-15 Partial nephrectomy also preserves long-term renal function16,17 while reducing overtreatment of patients with benign18 or clinically indolent19 tumors.

Despite these potential benefits to patients, population-based data suggest that the adoption of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy has been gradual and concentrated among select hospitals.4,12 Consequently, open radical nephrectomy remains the predominant surgical therapy for Americans with kidney cancer.3,4,12 Few data are available to clarify whether current practice patterns for partial nephrectomy and renal laparoscopy reflect differences in kidney cancer patients or differences in the practice styles of their surgeons.

We hypothesized that surgeon-level factors influence the use of nephron-sparing and/or minimally invasive surgery more than do a patient’s demographic or disease-related characteristics. We evaluated this hypothesis by using multilevel analyses to estimate the proportion of surgeon- and patient-attributable variance in the use of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy while simultaneously accounting for clustering of kidney-cancer patients within a surgeons’ practice.20,21 By clarifying the relative contribution of surgeon factors and patient factors, we may be able to use these data to inform efforts to accelerate the adoption of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy. Such adoption could, in turn, yield improved health outcomes among kidney cancer survivors.

Methods

Data source

We used linked data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to identify and characterize a population-based cohort of older patients (≥ 66 years) with incident kidney cancer diagnosed from 1997 through 2002. SEER is a population-based cancer registry that collects data regarding incidence, treatment and mortality. The demographic composition, cancer incidence, and mortality trends in the SEER registries are representative of the entire United States population.22

From 1997 through 1999, 11 SEER-affiliated registries (San Francisco, San Jose, Los Angeles, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, Seattle, Utah, and Atlanta) provided incident cases for linkage with health care claims covered by the CMS. In 2000, the SEER-Medicare dataset expanded to include cases from the Greater California, Louisiana, New Jersey and Kentucky tumor registries. The Medicare program provides primary health insurance for 97% of the United States population 65 years and older.23 Successful linkage with CMS claims is achieved for more than 90% of Medicare patients whose cancer-specific data are tracked by SEER.23

Cohort identification

We identified a preliminary cohort of 6,515 Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed between 1997 and 2002 with localized/regional, non-urothelial kidney cancer. For each case in the preliminary cohort, we then searched both inpatient (Medicare Provider Analysis and Review [MEDPAR] file, based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9) codes) and physician claims (Carrier Claims file, based on American Medical Association Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and ICD-9 codes) for kidney cancer—specific diagnosis and procedure codes.

Of these beneficiaries, we excluded 1,026 who lacked claims denoting surgical treatment for kidney cancer. We also excluded 3 patients (6 cases) whose claims suggested the presence of bilateral tumors at diagnosis. This process yielded a final analytic cohort of 5,483 cases (84.2% of the preliminary cohort).

Surgical procedures

Next, we defined and applied a claims-based algorithm to determine the type of surgical therapy received by each patient in the analytic cohort. Recognizing that specific CPT codes for laparoscopic radical (introduced in 2000) and laparoscopic partial (introduced in 2002) nephrectomy did not exist during the earlier years of the study, we identified laparoscopic cases using both direct (CPT) and indirect (ICD-9 and CPT) laparoscopy codes.2,4,24 We also ascribed a laparoscopic approach to patients with a live discharge and length of stay ≤ 2 days following radical or partial nephrectomy.2,4,24 Using this algorithm, we assigned each case to one of four mutually exclusive surgical categories: (1) open radical nephrectomy; (2) open partial nephrectomy; (3) laparoscopic radical nephrectomy; (4) laparoscopic partial nephrectomy.

As validation, we assessed the level of concordance between our claims-based algorithm and the type of cancer-directed surgery specified for each patient in the SEER data file (Patient Entitlement and Diagnosis Summary File). Although SEER does not collect data regarding whether the surgical approach was open or laparoscopic, we observed 97% agreement for the assignment of partial versus radical nephrectomy (κ=0.83). Also, we identified relevant surgical pathology claims within 30 days of the index admission for more than 95% of analyzed cases, thus supporting the occurrence of cancer-directed surgery.

Patient-level covariates

We used SEER variables to ascertain demographic and cancer-specific information (i.e., age at surgery, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, SEER registry, year of surgery, tumor size) for each case in the analytic cohort. We collapsed tumor size into two clinically relevant groups based on a 4 cm threshold.14 We assigned median Census-tract income and Census-tract percentage of non-high school graduates as patient-level measures of income and education, respectively.25

We measured preexisting comorbidity using a modification of the Charlson Index26 by identifying comorbid conditions (which include diabetes, renal insufficiency and cardiovascular disease) from inpatient and physician claims submitted during the 12-month period before the index admission for kidney cancer surgery.27 We also noted the presence or absence of hypertension, urolithiasis, and/or renovascular disease, given their relevance to surgical decision-making among patients with kidney cancer.

Primary surgeon

To identify the primary surgeon for each case, we used encrypted Unique Physician Identifier Numbers (UPIN) submitted with Medicare physician claims. Using claims from 1991–2002, we also determined each surgeon’s average annual nephrectomy (partial or radical) volume. We empirically defined high-volume surgeons as those performing at least 3 annual cancer-related nephrectomies among the SEER-Medicare population (83rd percentile). This measure of case volume may not reflect the total number of nephrectomies performed by a provider: It fails to account for surgeries among younger (non-Medicare-eligible) patients, Medicare HMO enrollees, and/or fee-for-service Medicare participants who reside outside of the SEER registries.

Statistical analysis

Prior to fitting multilevel models, we performed several univariate analyses. We used chi-square tests to evaluate the level of association between surgical procedure and various patient-level covariates and to assess the statistical significance of temporal surgical trends.

For our multilevel analyses, we defined the following primary outcomes: (1) use of partial nephrectomy and (2) use of laparoscopy among patients treated with radical nephrectomy. We hypothesized a priori that kidney cancer patients are nested within surgeons’ practices. Within this conceptual framework, we fit multilevel models (also known as hierarchical generalized linear models) to estimate surgeon- and patient-level contributions to observed variations in the use of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy for radical nephrectomy.20,21 Each model included a unique surgeon identifier as a random-effects term.20,21

In a first set of models (i.e., one for partial nephrectomy and one for laparoscopic radical nephrectomy), we estimated the surgeon-attributable residual intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). The residual ICC estimates the proportion of the “left-over” or unexplained variance in use of partial nephrectomy or laparoscopic radical nephrectomy attributable to unmeasured surgeon factors (rather than, for instance, unmeasured patient or hospital factors), after accounting for the variance explained by measured variables such as patient demographics, prevalent comorbidity, tumor size, and surgeon case-volume classification. For the partial nephrectomy outcome, we fit an additional model based on a sub-sample of patients who were diagnosed in 2000 or later and whose tumors were 4 cm or smaller (i.e., the sub sample of patients for whom partial nephrectomy may have been most appropriate).

Next, we fit a series of models that estimated the proportion of total variance (in use of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy for radical nephrectomy) explained by the surgeon factors, and specific patient and tumor characteristics. For this step, the initial model (known as the “unconditional model”) included only a surgeon-level random effects term; from the unconditional models, we calculated the surgeon-attributable variance without adjustment for case-volume, patient characteristics, or tumor characteristics. We then estimated the proportion of total variance explained by patient demographics, patient comorbidity, tumor size, and surgeon volume classification by fitting separate models (for each outcome) that included both a surgeon-level random effects term and only one of the following fixed effect covariate subsets: (1) surgeon case-volume; (2) patient demographics; (3) medical comorbidity; and (4) tumor size.

As sensitivity analyses, we calculated the residual ICC attributable to surgeons based on procedure assignment without the length-of-stay assumption for laparoscopy, as well as based on a sub sample of patients (n=3,989) whose case assignment used only direct CPT and ICD-9 codes. We also repeated the primary analyses after limiting our sample to patients whose surgeon performed at least three nephrectomies during the study period. We were unable to fit models that also included surgeon-level covariates, such as year of medical school graduation and practice structure, due to computational limitations.

All statistical testing was two-sided, completed using computerized software (SAS v9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and carried out at the 5% significance level. We obtained approval for this study from the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Results

Analytic cohort

We identified a final analytic cohort comprising 5,483 Medicare beneficiaries treated surgically for an incident kidney cancer diagnosed between 1997 and 2002. Table 1 presents demographic and clinical characteristics for patients in the analytic sample. During the study interval, 611 (11.1%) patients underwent partial nephrectomy (43 performed laparoscopically), and 4,872 (88.9%) underwent radical nephrectomy (515 performed laparoscopically). We observed differences in treatment patterns by sex, marital status, SEER registry, income, tumor size, and prevalent hypertension diagnosis (all p-values < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of patient characteristics by procedural strata (1997-2002)

| LAPAROSCOPIC PARTIAL NEPHRECTOMY (LPN) n (%) |

OPEN PARTIAL NEPHRECTOMY (OPN) n (%) |

LAPAROSCOPIC RADICAL NEPHRECTOMY (LRN) n (%) |

OPEN RADICAL NEPHRECTOMY (ORN) n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | 43 (0.8) | 568 (10.4) | 515 (9.4) | 4,357 (79.5) |

| PATIENT-LEVEL COVARIATES | ||||

| Age at surgery | ||||

| 66–69 years | 12 (1.1) | 142 (12.6) | 92 (8.2) | 880 (78.1) |

| 70–74 years | 11 (0.7) | 183 (10.8) | 143 (8.4) | 1,359 (80.1) |

| 74–79 years | 7 (0.5) | 156 (10.6) | 149 (10.1) | 1,164 (78.8) |

| 80–84 years | 9 (1.0) | 68 (7.8) | 95 (10.9) | 698 (80.3) |

| ≥85 years | < 5 (1.3) | 19 (6.0) | 36 (11.4) | 256 (81.3) |

| Sex* | ||||

| Male | 13 (0.6) | 216 (9.5) | 234 (10.3) | 1,801 (79.6) |

| Female | 30 (0.9) | 352 (10.9) | 281 (8.8) | 2,556 (79.4) |

| Race/ ethnicity | ||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 39 (0.8) | 468 (10.3) | 441 (9.7) | 3,615 (79.2) |

| White, Hispanic | < 5 (0.3) | 33 (9.8) | 22 (6.6) | 279 (83.3) |

| Black | < 5 (0.8) | 46 (11.6) | 32 (8.1) | 315 (79.5) |

| Other or unknown race/ethnicity | < 5 (0) | 21 (11.1) | 20 (10.6) | 148 (78.3) |

| Marital Status †, * | ||||

| Married | 31 (0.9) | 362 (10.8) | 312 (9.3) | 2,648 (79.0) |

| Not married | 10 (0.5) | 184 (9.6) | 186 (9.7) | 1,539 (80.2) |

| SEER Registry * | ||||

| Atlanta | < 5 (1.8) | 12 (7.1) | 15 (8.8) | 140 (82.4) |

| Connecticut | < 5 (0.6) | 48 (9.6) | 50 (10.0) | 400 (79.8) |

| Detroit | 6 (0.9) | 82 (12.3) | 57 (8.5) | 522 (78.3) |

| Greater California | < 5 (0.5) | 50 (8.5) | 62 (10.5) | 476 (80.5) |

| Hawaii | < 5 (0) | < 5 (4.7) | < 5 (4.7) | 58 (90.6) |

| Iowa | < 5 (0.2) | 48 (9.0) | 25 (4.7) | 460 (86.1) |

| Kentucky | < 5 (0.8) | 34 (9.4) | 42 (11.5) | 285 (78.3) |

| Los Angeles | 8 (1.5) | 79 (14.4) | 43 (7.8) | 419 (76.3) |

| Louisiana | 5 (1.5) | 29 (9.0) | 43 (13.4) | 245 (76.1) |

| New Jersey | 7 (1.0) | 78 (10.8) | 91 (12.5) | 549 (75.7) |

| New Mexico | < 5 (0) | 12 (7.1) | 10 (6.0) | 146 (86.9) |

| Rural Georgia | < 5 (0) | < 5 (5.9) | < 5 (17.7) | 13 (76.5) |

| San Francisco | < 5 (0.5) | 30 (15.4) | 25 (12.8) | 139 (71.3) |

| San Jose | < 5 (0) | 15 (11.0) | 7 (5.1) | 115 (83.9) |

| Seattle | < 5 (0.6) | 28 (8.4) | 28 (8.4) | 276 (82.6) |

| Utah | < 5 (0.7) | 19 (13.1) | 11 (7.6) | 114 (78.6) |

| Median census tract income ‡, ** | ||||

| < $ 35,000 | 9 (0.7) | 120 (9.3) | 112 (8.7) | 1,050 (81.3) |

| $ 35,000–$ 44,999 | 8 (0.6) | 132 (10.4) | 101 (7.9) | 1,033 (81.1) |

| $ 45,000–$ 59,999 | 13 (0.9) | 148 (10.2) | 154 (10.7) | 1,128 (78.2) |

| ≥$ 60,000 | 12 (0.9) | 147 (11.3) | 132 (10.2) | 1,005 (77.6) |

|

Percentage of residents in Census tract with less than high school education § |

||||

| > 25.0 | 8 (0.7) | 124 (10.5) | 101 (8.6) | 944 (80.2) |

| 15.1–25.0 | 11 (0.9) | 108 (8.9) | 114 (9.4) | 979 (80.8) |

| 10.0–15.0 | 8 (0.8) | 98 (9.9) | 107 (10.9) | 774 (78.4) |

| < 10.0 | 12 (0.8) | 175 (12.1) | 148 (10.2) | 1,116 (76.9) |

| Tumor Size ‘, * | ||||

| ≤4 cm | 34 (1.5) | 415 (17.7) | 260 (11.1) | 1,631 (69.7) |

| > 4 cm | 6 (0.2) | 112 (3.8) | 238 (8.0) | 2,604 (88.0) |

| Charlson Index score | ||||

| 0 | 22 (0.7) | 337 (10.4) | 319 (9.8) | 2,573 (79.1) |

| 1 | 11 (0.8) | 137 (10.2) | 120 (9.0) | 1,074 (80.0) |

| 2+ | 10 (1.1) | 94 (10.6) | 76 (8.5) | 710 (79.8) |

| Hypertension * | ||||

| Yes | 25 (0.9) | 305 (11.5) | 235 (8.8) | 2,092 (78.8) |

| No | 18 (0.6) | 263 (9.3) | 280 (9.9) | 2,265 (80.2) |

p<0.05 (χ2 general test)

p<0.05 (χ2 test for linear trend)

marital status unknown for 211 cases

income missing for 179 cases

education missing for 656 cases

tumor size missing for 183 cases.

Surgical practice patterns

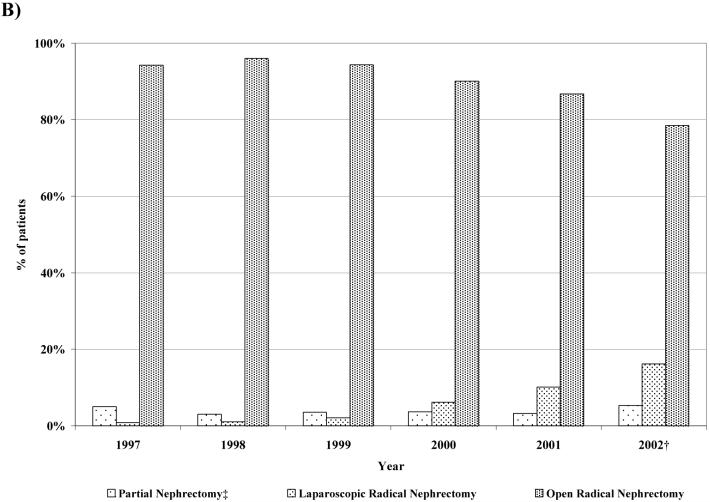

From 1997 to 2002, the proportion undergoing partial nephrectomy increased from 7.1% to 14.6% (p<0.01); for patients with tumors ≤ 4 cm, the proportion rose from 8.9% to 23.5% (p<0.01) (Figure 1a). Among patients with tumors ≤ 4 cm, laparoscopic radical nephrectomy increased from 1.2% to 20.3%; for patients with larger tumors laparoscopic radical nephrectomy increased from 0.8% to 16.2% (p-values <0.01) (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Trends in the surgical management of patients with kidney cancer, by tumor-size strata (1997–2002)

1a) Distribution of surgical therapies for patients with tumors ≤ 4 cm, 1997–2002

1b) Distribution of surgical therapies for patients with tumors > 4 cm, 1997–2002

In Table 2, we present the use of surgical procedures, stratified by co-morbidity, for 1997–1999 and 2000–2002, for comparison. During both periods, laparoscopic radical nephrectomy decreased among patients with greater co-morbidity. The proportion of partial nephrectomies (open or laparoscopic) remained similar across comorbidity strata.

Table 2.

Surgical therapies for early-stage kidney cancer, by year of diagnosis and Charlson Index (CI) strata*

| 1997–1999 | 2000–2002† | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPN n (%) |

OPN n (%) |

LRN n (%) |

ORN n (%) |

LPN n (%) |

OPN n (%) |

LRN n (%) |

ORN n (%) |

|

| CI = 0 | <5 | 78 (8.0) | 27 (2.8) | 871 (89.2) | 22 (1.0) | 259 (11.4) | 292 (12.8) | 1,702 (74.8) |

| CI = 1 | <5 | 23 (6.5) | 8 (2.3) | 320 (90.9) | 10 (1.0) | 114 (11.5) | 112 (11.3) | 754 (76.2) |

| CI ≥ 2 | <5 | 17 (7.5) | 4 (1.8) | 206 (90.7) | 10 (1.5) | 77 (11.6) | 72 (10.9) | 504 (76.0) |

p > 0.20 (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test)

Includes a small number of cases diagnosed in late 2002, surgery for whom was not performed until 2003.

Multi-level models

We identified 1,632 primary surgeons who performed 5,025 kidney cancer surgeries (92% of all cases in analytic cohort) during the study interval. Among the cases with identifiable primary surgeons, 364 different surgeons performed 556 open or laparoscopic partial nephrectomies (median=1; range=1–15). During the same interval, 4,469 patients underwent open or laparoscopic radical nephrectomy by 1,570 different surgeons (median=2; range=1–27). Among the latter group, we distinguished 262 surgeons who performed 495 laparoscopic procedures during the study period (median=1; range=1–12). In comparison, we identified 1,485 different primary surgeons for the 3,974 open radical nephrectomies (median=2; range=1–21).

We failed to identify a primary surgeon for 458 cases. Based on our empirical definition, we classified 138 (8.4%) providers as high-volume surgeons; 936 patients (18.6%) received treatment by a high-volume surgeon.

In addition to the 458 cases for whom we could not identify the primary surgeon, cases missing data for one or more independent variables were also excluded from multivariate analyses. Thus, our final partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy models included 3,995 (73% of the analytic sample) and 3,565 (80% of radical nephrectomies in the analytic sample) cases, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Surgeon and patient contributions to variance in use of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy (1997–2002)

| 1997–2002 (All patients) |

2000–2002 (Tumor size ≤ 4 cm) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Partial Nephrectomy | Laparoscopy† | Partial Nephrectomy | |

| Characteristic | |||

| Number of patients | 3,995 | 3,565 | 1,364 |

| Number of urologists | 1,487 | 1,426 | 820 |

|

Proportion of variance attributable to surgeon (residual intraclass correlation coefficient)‡ |

18.1% | 37.4% | 21.6% |

| Partitioned variances§ | |||

| Unmeasured surgeon factors | 17.5% | 37.5% | 21.7% |

|

Surgeon nephrectomy case- volume |

4.5% | 13.9% | 6.4% |

| Patient demographics | 7.4% | 20.7% | 9.4% |

| Comorbidity | 4.7% | 13.4% | 6.7% |

| Tumor size | 19.6% | 14.6% | — |

The multilevel model for use of laparoscopy was based on the sub sample of patients treated with radical nephrectomy

This row presents percentage of variance attributable to the surgeon after adjusting for patient and tumor characteristics, as well as surgeon nephrectomy case-volume (the residual intraclass correlation coefficient). The denominator for calculation of this proportion includes the residual variance attributable to the surgeon random effect (after adjustment for patient demographics, comorbidity, tumor size, and surgeon case-volume), and the variance attributable to unmeasured patient or tumor variables plus error (see Appendix 4; Model 4.2 and Equation 4.1).

The denominator for the calculation of partitioned-variance proportions is the total variance (see Appendix 4; Models 4.3-4.7, Equations 4.2 and 4.3). The total variance includes three components: (1) the variance attributable to the surgeon (after adjustment for the corresponding fixed-effect covariate(s) in a given model); (2) the variance attributable to the corresponding measured covariate(s) (i.e., the fixed effects); and (3) the variance attributable to unmeasured patient or tumor variables plus error (see Appendix 4; Equation 4.3). The partitioned variance attributable to the surgeon is estimated using an “unconditional” model, which includes a surgeon-level random-effects term as the only independent variable; accordingly, the denominator for calculation of this percentage includes only two components: (1) the variance attributable to the surgeon, unadjusted for any other covariates, and (2) the variance attributable to unmeasured patient or tumor variables plus error (see Appendix 4; Equation 4.2).

Table 3 presents findings from our multilevel analyses. For both the partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy outcomes, we report the surgeon-attributable residual ICC, that is, the percentage of “left-over” or unexplained variance in the use of the procedure associated with the surgeon after adjusting for available patient demographics, comorbidity, tumor size and surgeon volume. Table 3 also presents the proportions of total variance in procedure use attributable to unmeasured surgeon factors, surgeon case-volume, patient demographics, comorbidity, and tumor size.

For our primary models, the proportion of variance explained by measured variables (patient demographics, comorbidity, tumor size and surgeon volume) was 22.5% and 23.2% for partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy, respectively. With respect to the remaining or “left-over” variance, the corresponding surgeon-attributable residual ICCs were 18.1% and 37.4%, respectively. When we fit the partial nephrectomy model for a sub sample of patients with small tumors (≤ 4cm) diagnosed between 2000 and 2002, the residual ICC for surgeons was 21.6% (Table 3).

With respect to partial nephrectomy, only the proportion of total variance attributable to tumor size (19.6%) exceeded that attributable to unmeasured surgeon factors (17.5%). Neither comorbidity nor surgeon volume explained more than 5% of the total variance in use of partial nephrectomy. The relative contribution of surgeon and patient factors was similar in analyses limited to patients with smaller tumors (≤ 4 cm) diagnosed between 2000 and 2002 (Table 3).

For our laparoscopy outcome, the percentage of total variance attributable to unmeasured surgeon factors (37.5%) was substantially higher than that attributable to surgeon case-volume (13.9%), tumor size (14.6%), comorbidity (13.4%), or patient demographics (20.7%) (Table 3).

The partitioned variances and residual ICC attributable to surgeons did not change substantively in sensitivity analyses

Discussion

This study has two principal findings. First, and consistent with prior population-based studies,2-4,12 the use of both open partial nephrectomy and laparoscopic radical nephrectomy increased gradually between 1997 and 2002; these trends notwithstanding, open radical nephrectomy remained through 2002 the predominant surgical therapy for older Americans with kidney cancer. Second, for both procedures, the proportion of total variance attributable to surgeon factors exceeded that for almost all patient and tumor characteristics, including tumor size and comorbidity. The ensuing inference is that a minority of elderly kidney-cancer patients receives nephron-sparing or minimally invasive surgery; moreover, surgeon-level determinants appear to influence the likelihood of receiving a partial nephrectomy, or a laparoscopic approach for radical nephrectomy, as much as or more than does a patient’s tumor size, demographic characteristics, or general medical health.

Our findings are clinically consequential insofar as the benefits of partial nephrectomy16,28 and laparoscopy7-9 support the application of one or both of these techniques for a majority (rather than a minority) of patients with organ-confined renal tumors. Evidence for the feasibility of this paradigm comes from multiple contemporary case series wherein more than half of patients with tumors ≤ 4 cm underwent a partial nephrectomy (or other kidney-sparing technique); at these centers, most of the patients not receiving kidney-sparing treatment underwent laparoscopic radical nephrectomy.5,6,29 That (even in 2002) two out of three Medicare beneficiaries with kidney cancer received an open radical nephrectomy highlights an opportunity for population-level improvements in the quality of surgical care. In fact, it is elderly patients who may benefit most from treatments that preserve renal function and/or ease post-operative convalescence.

Reducing clinical uncertainty is a necessary step toward the goal of optimizing surgical practice patterns. The debut of (and progressively broadening indications for) partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy fragmented professional consensus regarding the standard therapy for patients with small, organ-confined renal masses.11,30-32 Emblematic of this concern is the finding that both open partial nephrectomy and laparoscopic radical nephrectomy are most frequently used among patients with small tumors (≤ 4 cm) and little comorbidity. Likewise, the persistently high proportion of surgeon-attributable variance among patients with tumors ≤ 4 cm (i.e., those for whom partial nephrectomy may have been most feasible) further underscores the extant uncertainty regarding the relative benefits of kidney-sparing and minimally-invasive surgery.

In the setting of such uncertainty, individual surgeons may have developed distinctive approaches to the treatment of otherwise-similar patients with kidney cancer (so-called surgical signatures). 33,34 That the percentage of provider-attributable variance in our analysis is higher than that reported in other clinical studies 35,36 employing multilevel modeling techniques supports the validity of this hypothesis and highlights the need for additional studies and/or consensus-based clinical guidelines that clarify optimal kidney-cancer surgical treatment algorithms (including the appropriate integration of ablative therapies 37 and surveillance protocols 38 ).

Although these data are consistent with the proposition that a surgeon’s kidney-cancer case volume is associated with the use of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy,4,12 the relatively greater percentage of variance attributable to non-volume-related surgeon factors underscores the potential leverage of other provider-adoption barriers related to technical complexity,39,40 practice setting,41,42 and informational resources.42 For instance, during the years studied, few practicing urologists received formal training in laparoscopy; moreover, relatively small kidney cancer caseloads further deterred uptake of this technique.40,43 In view of these barriers, several mentored and simulator-based training programs have since emerged to facilitate skill transfer from experienced to laparoscopy-naïve urologists.44-46

The high percentage of provider-attributable variance may also reflect unmeasured differences in practice setting (and consequent access to information) among surgeons in our sample. That is, most providers make conclusive decisions about innovations based on interactions with local peer adopters rather than on scientific research or mass-media channels.40,42 For the use of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy, therefore, the high proportion of surgeon-attributable variance may signify an asymmetric distribution of local surgical colleagues who assess the procedure, refine its application, and then use informal communication channels to facilitate propagation among other potential adopters in their community.5,40,42 Recognizing that social connections and local informational resources facilitate the diffusion of new surgical therapies,39,40,42,47 we see innovative collaborations between academic and community urologists—informed by established practice-based surgical research models48-51—as representing a potential mechanism for accelerating the adoption of partial nephrectomy and renal laparoscopy.

Alternatively, it is possible that payer-initiated referral policies could emerge that circumvent adoption barriers by promoting the concentration of surgical care among providers with established proficiency in the spectrum of kidney-cancer surgical treatment options (the “centers-of-excellence” model).48 This potential policy lever has several limitations, including its reliance on imperfect methods for identifying “excellent” providers;48 its indifference to patient preferences for where they receive care;52 its potential to yield delays in care as a result of saturation of designated providers;53 its failure to address the obstacles encountered by surgeons endeavoring to adopt beneficial innovations;40,51 and its assumption that variations in convalescence and morbidity (as opposed to mortality) sufficiently motivate a policy-based intervention.

Ultimately, development of specific interventions to increase the use of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy will be informed by future studies that further characterize surgeon- (e.g., attitudes, practice structure and setting) and hospital- level (e.g., technology, ancillary staff) determinants of adoption, as well as patient preferences.

Our study has several limitations. First, current SEER-Medicare data reflect the earlier years following urologists’ acceptance of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy; more-recent data may reveal expanded utilization of these techniques with a smaller percentage of provider-attributable variance.54 There is evidence, however, that utilization remained stable in 2003 and 2004.2,55 Second, its generalizability is restricted by a sample that is limited to patients who are ≥66 years of age who have traditional feefor-service Medicare coverage. Nonetheless, linked SEER-Medicare data provide a unique opportunity to evaluate variations in kidney cancer care in the context of clinically important case-mix variables including tumor size and medical comorbidity. Third, we could not explicitly measure all clinical variables that are relevant to surgical decision making. Consequently, we were unable to distinguish reliably the cases with recognized contraindications to nephron-sparing and/or minimally-invasive surgery. Fourth, we defined high-volume surgeons empirically rather than based on existing criteria; alternative volume thresholds may have changed the proportion of variance explained by surgeon case-volume.

Fifth, while we posit that expanded use of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy is a desirable goal, we also recognize that clarifying the optimal use will require a better understanding of patient preferences. This is particularly relevant given the potentially dissimilar non-oncologic outcomes (e.g., intensity of convalescence, short-term complications) following different surgical therapies. Sixth, our algorithm for surgical-procedure assignment necessarily assigns a single treatment for the small number of cases with a discrepancy in surgical procedure classification based on inpatient versus physician claims. As such, our primary outcome is susceptible to some degree of misclassification; however, sensitivity analyses confirmed our principal findings. Finally, our findings are subject to potential selection bias based on observed differences (e.g., sex, race, income) between cases that were excluded and those that were included in our multivariable models. The observed differences, however, were small in magnitude and lacked clinical significance. In addition, excluded and included cases did not differ in tumor size, education, or marital status and the two groups were similar with respect to the distribution of surgical therapies.

This paper describes patterns of surgical care for elderly Americans with kidney cancer. Specifically, despite their potential advantages relative to open radical nephrectomy, partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy are used relatively infrequently in this population; moreover, much of the variance in their use is attributable to surgeon-specific, rather than to patient- or tumor-specific, factors. Thus, for many older patients with kidney cancer, the surgery provided may depend more on their surgeon’s practice style than on the characteristics of the patient and his or her disease. Consequently, the timely dismantling of residual barriers to surgeons’ adoption of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy is an important step toward improving the quality of care provided to patients with kidney cancer.

Acknowledgement

Ralph V. Clayman, MD, Department of Urology, University of California, Irvine, provided constructive comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. He received no compensation for his review. Marian Branch, RAND Health, provided compensated editorial feedback.

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (N01-DK-1-2460 — The Urologic Diseases in America project). David C. Miller, MD, MPH is additionally supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (NIH-1-F32 CA123819-01), the American Cancer Society (PF CPHPS-112124) and the American Urological Association Foundation Research Scholar Program.

Footnotes

Condensed Abstract Partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy are used relatively infrequently among US Medicare beneficiaries with kidney cancer and most of the variance in their use is attributable to surgeon-specific, rather than to patient- or tumor-specific, factors. Consequently, dismantling residual barriers to surgeons’ adoption of partial nephrectomy and laparoscopy is an important step toward improving the quality of care provided to patients with kidney cancer.

References

- 1.Novick AC. Laparoscopic and partial nephrectomy. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6322S–6327S. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-050003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller DC, Wei JT, Dunn RL, Hollenbeck BK. Trends in the diffusion of laparoscopic nephrectomy. JAMA. 2006;295:2480–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller DC, Hollingsworth JM, Hafez KS, Daignault S, Hollenbeck BK. Partial nephrectomy for small renal masses: an emerging quality of care concern? J Urol. 2006;175:853–857. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller DC, Taub DA, Dunn RL, Wei JT, Hollenbeck BK. Laparoscopy for renal cell carcinoma: diffusion versus regionalization? J Urol. 2006;176:1102–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Permpongkosol S, Bagga HS, Romero FR, Solomon SB, Kavoussi LR. Trends in the operative management of renal tumors over a 14-year period. BJU Int. 2006;98:751–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhayani SB, Belani JS, Hidalgo J, Figenshau RS, Landman J, Venkatesh R, et al. Trends in nephron-sparing surgery for renal neoplasia. Urology. 2006;68:732–736. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf JS, Merion RM, Leichtman AB, Campbell DA, Jr, Magee JC, Punch JD, et al. Randomized controlled trial of hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open surgical live donor nephrectomy. Transplantation. 2001;72:284–290. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200107270-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simforoosh N, Basiri A, Tabibi A, Shakhssalim N, Hosseini Moghaddam SM. Comparison of laparoscopic and open donor nephrectomy: a randomized controlled trial. BJU Int. 2005;95:851–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oyen O, Andersen M, Mathisen L, Kvarstein G, Edwin B, Line PD, et al. Laparoscopic versus open living-donor nephrectomy: experiences from a prospective, randomized, single-center study focusing on donor safety. Transplantation. 2005;79:1236–1240. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000161669.49416.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunn MD, Portis AJ, Shalhav AL, et al. Laparoscopic versus open radical nephrectomy: a 9-year experience. J Urol. 2000;164:1153–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Best S, Ercole B, Lee C, Fallon E, Skenazy J, Monga M. Minimally invasive therapy for renal cell carcinoma: is there a new community standard? Urology. 2004;64:22–25. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollenbeck BK, Taub DA, Miller DC, Dunn RL, Wei JT. National utilization trends of partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: a case of underutilization? Urology. 2006;67:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fergany AF, Hafez KS, Novick AC. Long-term results of nephron sparing surgery for localized renal cell carcinoma: 10-year followup. J Urol. 2000;163:442–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hafez KS, Fergany AF, Novick AC. Nephron sparing surgery for localized renal cell carcinoma: impact of tumor size on patient survival, tumor recurrence and TNM staging. J Urol. 1999;162:1930–1933. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee CT, Katz J, Shi W, Thaler HT, Reuter VE, Russo P. Surgical management of renal tumors 4 cm. or less in a contemporary cohort. J Urol. 2000;163:730–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang WC, Levey AS, Serio AM, Snyder M, Vickers AJ, Raj GV, et al. Chronic kidney disease after nephrectomy in patients with renal cortical tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:735–740. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70803-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCullogc CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kutikov A, Fossett LK, Ramchandani P. Incidence of benign pathologic findings at partial nephrectomy for solitary renal mass presumed to be renal cell carcinoma on preoperative imaging. Urology. 2006;68:737–740. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hollingsworth JM, Miller DC, Daignault S, Hollenbeck BK. Rising incidence of small renal masses: a need to reassess treatment effect. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1331–1334. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subramanian S, Jones K, Duncan C. Multilevel methods for public health research. In: Kawachi I, Berkman L, editors. Neighborhoods and Health. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2003. pp. 65–111. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snijders T, Bosker R. Multilevel Analysis. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hankey BF, Ries LA, Edwards BK. The surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program: a national resource. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:1117–1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finlayson SR, Laycock WS, Birkmeyer JD. National trends in utilization and outcomes of antireflux surgery. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:864–867. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8965-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bach PB, Guadagnoli E, Schrag D, Schussler N, Warren JL. Patient demographic and socioeconomic characteristics in the SEER-Medicare database applications and limitations. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-19–25. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klabunde CN, Harlan LC, Warren JL. Data sources for measuring comorbidity: a comparison of hospital records and medicare claims for cancer patients. Med Care. 2006;44:921–928. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223480.52713.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russo P. Partial nephrectomy achieves local tumor control and prevents chronic kidney disease. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006;6:1745–1751. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.12.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hollingsworth JM, Miller DC, Dunn RL, Montgomery JS, Roberts WW, Hafez KS, et al. Surgical management of low-stage renal cell carcinoma: technology does not supersede biology. Urology. 2006;67:1175–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhayani SB, Clayman RV, Sundaram CP, Landman J, Andriole G, Figenshau RS, et al. Surgical treatment of renal neoplasia: evolving toward a laparoscopic standard of care. Urology. 2003;62:821–826. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00670-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scherr DS, Ng C, Munver R, Sosa RE, Vaughan ED, Del Pizzo J. Practice patterns among urologic surgeons treating localized renal cell carcinoma in the laparoscopic age: technology versus oncology. Urology. 2003;62:1007–1111. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00773-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lotan Y, Duchene DA, Cadeddu JA, Sagalowsky AI, Koeneman KS. Changing management of organ-confined renal masses. J Endourol. 2004;18:263–268. doi: 10.1089/089277904773582877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baicker K, Chandra A, Skinner JS, Wennberg JE. Who you are and where you live: how race and geography affect the treatment of medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) Suppl Web Exclusive. 2004:VAR33–44. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.var.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinstein JN, Bronner KK, Morgan TS, Wennberg JE. Trends and geographic variations in major surgery for degenerative diseases of the hip, knee, and spine. Health Aff (Millwood) Suppl Web Exclusive. 2004:VAR81–89. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.var.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shahinian VB, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Determinants of androgen deprivation therapy use for prostate cancer: role of the urologist. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:839–845. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hawley ST, Hofer TP, Janz NK, et al. 2006. Correlates of between-surgeon variation in breast cancer treatments Med Care 200644609–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aron M, Gill IS. Minimally Invasive Nephron-Sparing Surgery (MINSS) for Renal Tumours Part II: Probe Ablative Therapy. Eur Urol. 2007;51:348–357. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kunkle DA, Crispen PL, Chen DY, Greenberg RE, Uzzo RG. Enhancing renal masses with zero net growth during active surveillance. J Urol. 2007;177:849–854. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sachdeva AK. Acquiring skills in new procedures and technology: the challenge and the opportunity. Arch Surg. 2005;140:387–389. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. Free Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McFall SL, Warnecke RB, Kaluzny AD, Ford SL. Practice setting and physician influences on judgments of colon cancer treatment by community physicians. Health Serv Res. 1996;31:5–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Escarce JJ. Externalities in hospitals and physician adoption of a new surgical technology: an exploratory analysis. J Health Econ. 1996;15:715–734. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(96)00501-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carroll PR, Albertsen PC, Smith JA, Howards SS. Volume of major surgeries performed by recent and more senior graduates from North American urology training programs. J Urol. 2006;175(supplement):1. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corica FA, Boker JR, Chou DS, White SM, Abdelshehid CS, Stoliar G, et al. Short-term impact of a laparoscopic “mini-residency” experience on postgraduate urologists' practice patterns. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:692–698. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDougall EM, Corica FA, Boker JR, Sala LG, Stoliar G, Borin JF, et al. Construct validity testing of a laparoscopic surgical simulator. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:779–787. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shalhav AL, Dabagia MD, Wagner TT, Koch MO, Lingeman JE. Training postgraduate urologists in laparoscopic surgery: the current challenge. J Urol. 2002;167:2135–2137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Myers JA, Doolas A. How to teach an old dog new tricks and how to teach a new dog old tricks: bridging the generation gap to push the envelope of advanced laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1177–1178. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-0598-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Birkmeyer NJ, Birkmeyer JD. Strategies for improving surgical quality--should payers reward excellence or effort? N Engl J Med. 2006;354:864–870. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb053364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gagliardi A, Ashbury FD, George R, Irish J, Stern HS. Improving cancer surgery in Ontario: recommendations from a strategic planning retreat. Can J Surg. 2004;47:270–276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wibe A, Moller B, Norstein J, Carlsen E, Wiig JN, Heald RJ, et al. A national strategic change in treatment policy for rectal cancer--implementation of total mesorectal excision as routine treatment in Norway. A national audit. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2002;45:857–866. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Westfall JM, Mold J, Fagnan L. Practice-based research--"Blue Highways" on the NIH roadmap. JAMA. 2007;297:403–406. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Finlayson SR. Delivering quality to patients. JAMA. 2006;296:2026–2027. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.16.2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dimick JB, Finlayson SR, Birkmeyer JD. Regional availability of high-volume hospitals for major surgery. Health Aff (Millwood) Suppl Web Exclusive. 2004:VAR45–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.var.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Katz SJ, Hawley ST. From policy to patients and back: surgical treatment decision making for patients with breast cancer. Health Aff. 2007;26:761–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer National Cancer Database: Public Access to Cancer Data: NCDB Public Benchmark Reports: Dx Year 2004, Primary Site Kidney/Renal Pelvis, Variable 1 Surg. Proc [accessed on May 25, 2007]. Available at: http://web.facs.org/ncdbbmr/frames/public7/TABLES/Y04S49XaTa_20000000_t b_B.html