Summary

The emergence of resistance to vancomycin and related glycopeptide antibiotics is spurring efforts to develop new antimicrobial therapeutics. High resolution structural information about antibiotic-ligand recognition should prove valuable in the rational design of improved drugs. We have determined the X-ray crystal structure of the complex of vancomycin with N-acetyl-D-Ala-D-Ala, a mimic of the natural muramyl peptide target, and refined this structure at a resolution of 1.3 Å to R and Rfree values of 0.172 and 0.195, respectively. The crystal asymmetric unit contains three back-back vancomycin dimers; two of these dimers participate in ligand-mediated face-face interactions that produce an infinite chain of molecules running throughout the crystal. The third dimer packs against the side of a face-face interface in a tight “side-side” interaction that involves both polar contacts and burial of hydrophobic surface. The trimer of dimers found in the asymmetric unit is essentially identical to complexes seen in three other crystal structures of glycopeptide antibiotics complexed with peptide ligands. These four structures are derived from crystals belonging to different space groups, suggesting that the trimer of dimers may not be simply a crystal packing artifact, and prompting us to ask if ligand-mediated oligomerization could be observed in solution. Using size exclusion chromatography, dynamic light scattering, and small-angle X-ray scattering, we demonstrate that vancomycin forms discrete supramolecular complexes in the presence of tripeptide ligands. Size estimates for these complexes are consistent with assemblies containing 4-6 vancomycin monomers.

Keywords: X-ray crystallography, glycopeptide antibiotics, antibiotic resistance, vancomycin, small-angle X-ray scattering

Introduction

Vancomycin has long functioned as an antibiotic of last resort, reserved for treating infections caused by bacteria resistant to more commonly used drugs. However, vancomycin resistance is becoming widespread, meaning that the drug will inevitably lose its utility 1. New drugs will be required to replace it, and considerable effort is being expended to develop improved versions of vancomycin or related glycopeptide antibiotics. A thorough structural and mechanistic understanding of how these drugs recognize their targets will aid in the rational design of new therapeutics.

Vancomycin acts by interfering with bacterial cell wall biosynthesis 2. It affects cell wall production at both the transglycosylase step, in which disaccharide building blocks are transferred to the growing glycan chain 3; 4, and the transpeptidase step, in which different peptidoglycan strands are crosslinked 5; 6. Vancomycin can block the transglycosylase step by sequestering the substrate of the transglycosylation enzyme 7 and/or by steric blockade of the enzyme’s access to the growing glycan chain 8. The drug blocks the transpepidation step by sequestering the muramyl peptide that is a substrate for the transpeptidase reaction. The details of muramyl peptide binding by vancomycin have been examined using solution NMR 9, and a number of high resolution crystal structures are available that show vancomycin in complex with small mimetics of the muramyl peptide 10–13. The antibiotic recognizes the three C-terminal residues of the muramyl peptide (Lys-D-Ala-D-Ala). The presence of additional residues N-terminal to this tripeptide does not alter the binding affinity, indicating that the tripeptide comprises all of the antibiotic binding determinants 14. Many of the known types of vancomycin resistance, including VanA, VanB, and VanD, alter the structure of the drug’s target so as to reduce its binding affinity, for example by replacing the normal muramyl peptide with a depsipeptide containing a C-terminal D-lactate 15; 16. This small change reduces vancomycin affinity for its target by three orders of magnitude.

Vancomycin is known to form noncovalent dimers 17–20, sometimes referred to as back-back dimers, since the dimerization surface is on the opposite side of the molecule from the ligand binding pocket. Dimerization and ligand binding are cooperative in vancomycin and many related glycopeptide antibiotics 21, and it seems likely that the increased avidity of ligand recognition by the dimer enhances biological activity. This observation has prompted efforts to produce covalently-linked multivalent forms of the drug, in the hopes of developing variants of vancomycin with increased activity against vancomycin-resistant strains (reviewed in Li & Bu 22). Certain covalent dimers have been found to be significantly more potent against vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) than is vancomycin itself 23–29. The structural basis of the enhanced activity of multimeric vancomycin derivatives is not yet understood, but it is intriguing to note that vancomycin and related drugs can assemble within crystals into supramolecular drug:ligand assemblies, in which intermolecular interactions are mediated in part by the muramyl peptide ligands 12; 30. If the packing interactions that control oligomerization in the crystalline phase prove to be similar to the interactions that contribute to the enhanced activity of the multivalent vancomycin derivatives, then rational engineering of these molecular interfaces may represent a path to improved therapeutics.

Since vancomycin shows maximum affinity for a tripeptide ligand, but no published structure was available for such a complex, we chose to determine the X-ray crystal structure of the complex of the drug with the tripeptide analog N-acetyl-D-alanine-D-alanine (N-Ac-D-Ala-D-Ala). This structure, reported herein, reveals the presence of supramolecular drug-ligand complexes that are essentially identical to those seen in crystal structures of other glycopeptide antibiotic-ligand complexes. The same supramolecular structure occurs in crystals belonging to different space groups, suggesting that its formation is not merely an artifact of crystallization. This observation prompted us to ask whether such ligand-mediated oligomerization events might also occur in solution. We demonstrate by a variety of biophysical methods that vancomycin assembles into oligomeric structures in solution, in a ligand-dependent manner.

Results

Crystal structure: Overall features

The crystal asymmetric unit contains six monomers, referred to as V1, V2,…,V6, as described previously 10; monomers 1–6 correspond to chain designations A–F, respectively, in the coordinate file. The individual peptide residues comprising each vancomycin monomer will be denoted as follows: V1:1, residue 1 of monomer V1; V4:5, residue 5 of monomer V4; etc.. The six monomers are arranged as three back-back dimers: V1–V2, V3–V4, and V5–V6. A peptide ligand is found in the binding site of all six monomers. Two of the back-back dimers (V1–V2 & V3–V4) form a ligand-mediated face-face interaction between V2 and V4 (Figure 1). The V1 and V3 monomers form face-face interactions with symmetry-related copies of each other, thereby forming a kinked infinite chain of vancomycin monomers, connected by alternating back-back and face-face interactions (Figure 2). This chain runs roughly parallel with the b-axis of the crystal unit cell. The third back-back dimer, V5–V6, is packed against the side of this chain, at the point where V2 and V4 are joined in a face-face interaction. On its opposite side, the V5–V6 dimer packs against a symmetry-related copy of itself and thereby connects adjacent chains of V1–V2 and V3–V4 dimers. This interaction represents the major crystal packing interaction in the x–z plane.

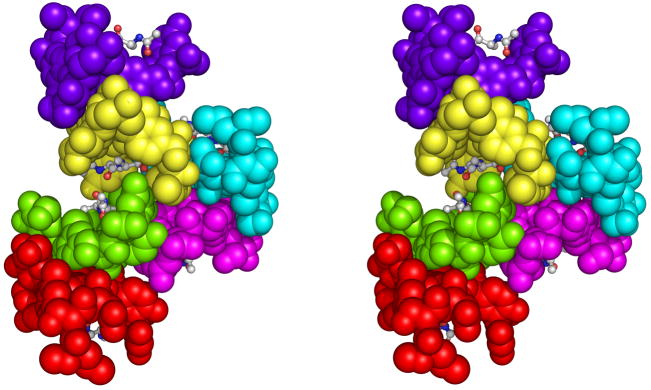

Figure 1.

Stereo view of the contents of the crystal asymmetric unit. Six vancomycin monomers are shown in a space-filling representation; each monomer is colored differently (red, green, yellow, purple, magenta, and cyan). The tripeptide ligands of each monomer are shown in ball-and-stick models, colored by element (carbon = gray, oxygen = red, nitrogen = blue). Figures 1 and 3–5 were made using PyMOL (DeLano, W.L., The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (2002); http://www.pymol.org).

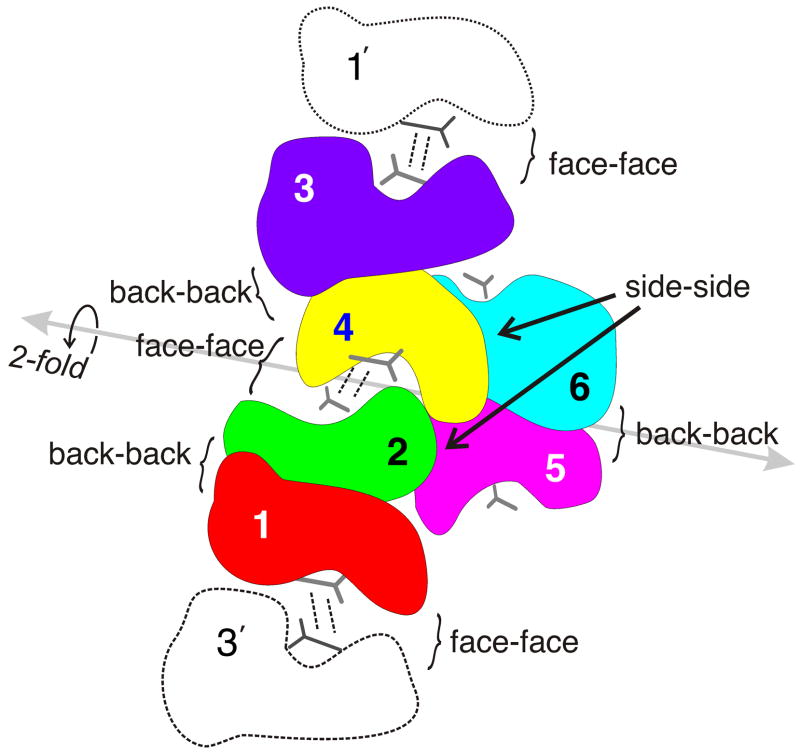

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the complex of six vancomycin monomers that comprise the crystal asymmetric unit, showing the numbering scheme for the different monomers. The point of view and color coding are the same as for Figure 1. The various types of interfaces found in the hexamer are labeled (back-back, face-face, side-side). The internal two-fold axis of pseudosymmetry is shown in gray. The positions of symmetry-related copies of monomers 1 and 3 are also shown (in white), and are labeled 1′ and 3′.

The six monomers in the asymmetric unit form a structure containing approximate two-fold symmetry. This two-fold pseudosymmetry axis passes through the V2/V4 face-face interface and the V5–V6 back-back interface (Figure 2); it relates molecules V1 to V3, V2 to V4, and V5 to V6. The entire hexameric asymmetric unit can be rotated around this two-fold axis and superimposed on itself with an RMS difference in Cα positions of 0.26 Å. The arrangement of carbohydrate residues on V1–V2 and V3–V4 is consistent with this two-fold symmetry; however, the carbohydrates on the V5–V6 dimer do not obey the two-fold symmetry, as is typical for back-back vancomycin dimers 31.

The spatial arrangement of the six monomers in the asymmetric unit of this crystal almost exactly recapitulates structures found in crystals of several other ligand complexes of glycopeptide antibiotics. Specifically, similar hexameric structures can be found in two different crystal forms of balhimycin complexed with cell wall peptides 30, and in an unpublished structure of vancomycin in complex with the diacetyl-Lys-D-Ala-D-Ala tripeptide 1. The hexameric assemblies from any of these four crystal structures can be superimposed upon one another with pairwise RMS differences in Cαpositions ranging from 0.3 to 0.7 Å. None of these other crystals is isomorphous with or belongs to the same spacegroup as the crystals described herein (Table 2). Yet another crystal form has been reported for vancomycin in complex with N-Ac-D-Ala-D-Ala 32; while no structure determination has been reported for these crystals, it is interesting to note that the asymmetric unit is calculated to contain twelve vancomycin-ligand units, which is exactly the correct size to correspond to two copies of our hexameric assembly.

Table 2.

Different crystal forms containing similar supramolecular antibiotic-ligand complexes

| PDB ID | Crystal contents | Spacegroup | Unit cell |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3E14 (this structure) | vancomycin + Ac-D-Ala-D-Ala | C2221 | a = 66.1 |

| b = 71.9 | |||

| c = 48.4 | |||

| 1FVM | vancomycin + Lys-D-Ala-D-Ala | P212121 | a = 35.6 |

| b = 36.4 | |||

| c = 65.7 | |||

| 1GO6 | balhimycin + Lys-D-Ala-D-Ala | P21212 | a = 88.9 |

| b = 28.0 | |||

| c = 50.7 | |||

| 1HHZ | balhimycin aglycon + Ala-Glu-Lys-D-Ala-D-Ala | P3221 | a = 48.3 |

| b = 48.3 | |||

| c = 39.3 |

Conformations of the antibiotic molecules

As has previously been observed for vancomycin, the back-back dimers in this structure are all asymmetric 31. The macrocyclic peptide cores of the two monomers forming each back-back dimer adopt approximate C2 symmetry, but this symmetry is violated by the two disaccharide groups of the dimer, which pack side-by-side in a parallel manner. Because the carbohydrate groups form part of the ligand binding pocket, the two binding sites in the back-back dimers are therefore nonequivalent.

The non-equivalence of the two halves of the dimer translates into small differences in conformation. Superposition of the aglycon portions of the two halves of a back-back dimer yields RMS differences in atomic positions of 0.5–0.8 Å. However, monomers with equivalent sugar positions from different back-back dimers are more similar. V1 and V3 are equivalent, in that they both have a vancosamine sugar overhanging their ligand binding site; similarly V2 and V4 are equivalent. Superposition of either V1 with V3 or V2 with V4 yields RMS differences of approximately 0.1 Å in atomic positions. Interestingly, V5 and V6, the two monomers that are not involved in the stack of alternating back-back and face-face monomers, are intermediate in their conformations. The vancosamine position makes V5 equivalent to V2 and V4, while V6 is equivalent to V1 and V3. Superposition of either V5 or V6 on V1 or V2 gives RMS differences of 0.4–0.8; V5 superposition onto V6 gives an RMS difference of 0.4 Å.

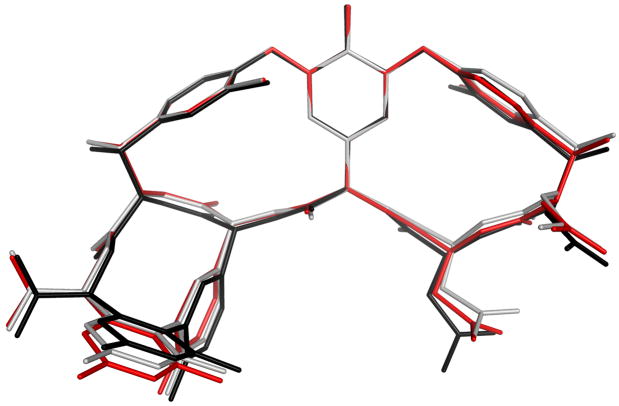

These differences reflect varying degrees of openness of the ligand binding site. The macrocyclic core of the antibiotic adopts a concave structure that curves around the ligand. The V2 and V4 structures close tightly around the ligand, whereas the binding pocket of V1 and V3 is more open (Figure 3). As predicted by the superposition calculations, V5 & V6 adopt conformations intermediate between V2/V4 and V1/V3.

Figure 3.

The superposition of monomers 1, 2, and 5 (shown in red, black, and gray, respectively). The carbohydrate moieties have been omitted for clarity.

Residue 1 adopts different conformations in each of the six vancomycin monomers in the asymmetric unit. V1:1 and V3:1 adopt similar conformations; V2:1 and V4:1 adopt a different conformation, but are similar to one another (Figure 3). As is the case with the conformation of the core macrocycle, residues V5:1 and V6:1 adopt conformations that are similar to one another and intermediate between the V1/V3 conformation and the V2/V4 conformation.

Based upon the conformations of the core macrocycle and residue one, the six vancomycin monomers in the asymmetric unit can be divided into three conformational categories: V1/V3, V2/V4, and V5/V6. These different conformations reflect the positions occupied by the monomers in the hexamer. V1 and V3 lie at the ends of the stack, and form face-face interactions with symmetry-related copies of each other. This interaction shows almost perfect two-fold rotational symmetry. Similarly V2 and V4 participate in a face-face interaction in the center of the stack which also shows almost perfect C2 symmetry. V5 and V6, in contrast, do not form any face-face interactions. They do, however, form a significant side-side interaction with V2 and V4. This tight interaction with the symmetric V2/V4 pair may impose some symmetry upon the V5/V6 pair.

Ligand binding

The ligand, N-acetyl-D-Ala-D-Ala, is a tripeptide mimetic, in which the N-acetyl group replaces the tripeptide’s N-terminal residue. Increasing the length of the ligand peptide beyond three residues does not change the ligand’s affinity for vancomycin 14; hence, it appears likely that the antibiotic-ligand interactions seen in this crystal structure represent the full complement of interactions that can be formed between vancomycin and its natural muramyl peptide ligand. The ligand lies in the binding site in an extended conformation and participates in an extensive pattern of hydrogen bonding with the antibiotic, forming essentially identical interactions to those seen in the balhimycin:tripeptide and balhimycin:pentapeptide complexes 30. The C-terminal carboxylate group forms hydrogen bonds with the peptide amide nitrogens of vancomycin residues 2, 3, and 4; the amide nitrogen of the C-terminal D-Ala residue hydrogen bonds with the peptide carbonyl of residue 5 (this is the hydrogen bond that is disrupted when resistant bacteria incorporate D-lactate into their cell wall peptides in the place of D-Ala); and the acetyl carbonyl oxygen hydrogen bonds with the amide nitrogen of residue 5. The first four of these hydrogen bonds have been observed in crystal structures of vancomycin and its congeners with small cell wall mimetics, but the fifth hydrogen bond is only possible with tripeptides or larger ligands.

Face-face interactions

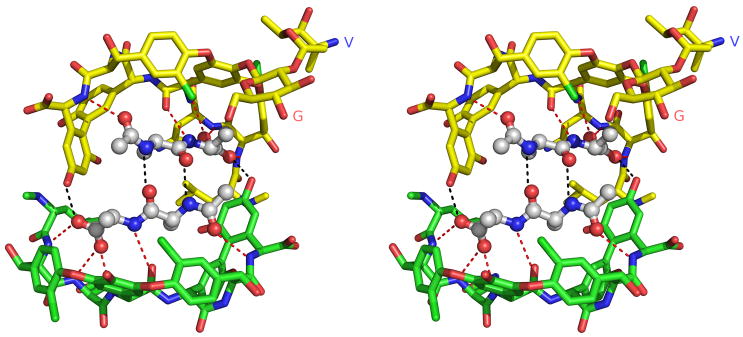

In addition to forming hydrogen bonds with the vancomycin monomer to which they are bound, the ligands in V1, V2, V3, and V4 also form hydrogen bonds across the face-face interface.

In the V2–V4 face-face dimer, each ligand forms two antiparallel β–type hydrogen bonds with the opposing ligand (Figure 4), linking the carbonyl oxygens and amide nitrogens of the penultimate D-Ala residues. In addition, a hydroxyl group from the resorcinol ring of the opposing vancomycin molecule hydrogen bonds to a carboxylate oxygen of the ligand’s C-terminal residue. Each ligand forms a total of 8 hydrogen bonds, five to the vancomycin monomer to which it is bound and 3 more across the face-face interface. The angle between the two facing ligand strands is approximately 220°.

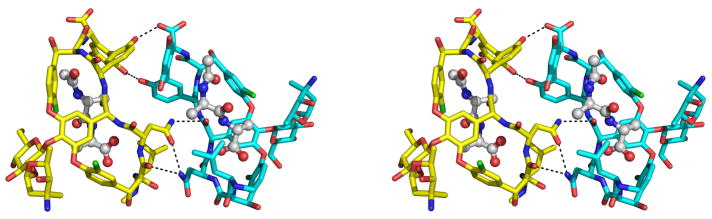

Figure 4.

Stereo view of the face-face interface formed by V2 (bottom, green) and V4 (top, yellow). The two ligands are shown in ball-and-stick representation. Hydrogen bonds between a ligand and the vancomycin molecule to which it is bound are shown in red; hydrogen bonds across the face-face interface are shown in black. For the sake of clarity, the disaccharide moiety of V2 has been omitted. The disaccharide moiety of V4 is shown, with the glucose and vancosamine sugars labeled G and V, respectively. Rotating the molecules shown in this figure by approximately 30° about a vertical axis would result in an orientation similar to that shown in Figure 1.

In the V1–V3 face-face dimers, this basic pattern of hydrogen bonding is retained. However, the angle between the facing peptide ligands is more pronounced, and the face-face interaction is kinked relative to that seen between V2 and V4. This kink precludes a direct hydrogen bond between the resorcinol hydroxyl and the carboxylate of the facing ligand; instead, a water molecule bridges these two atoms. The kink may be due purely to crystal packing considerations, or it may reflect the different carbohydrate structures present at the V1–V3 and V2–V4 interfaces: A glucose overhangs the V2/V4 ligand binding site, whereas in V1 and V3 the vancosamine sugar lies atop the binding site.

The hydrogen bonds that define the face-face interaction between V2 and V4 are very similar to those seen in the two balhimycin complexes with cell wall mimetics 30 and the PDB structure 1FVM. This interface is therefore likely to represent a general mode of oligomerization for vancomycin complexes with cell wall peptides. On the other hand, the V1–V3 face-face interaction is not found in any other crystal structure of which we are aware, and hence is more likely to represent a variant of the face-face interaction that has been imposed by crystal packing. The surface area buried upon formation of both face-face interactions is significant (over fifteen percent of the total surface area of the monomer), and approaches the area buried during the formation of back-back dimers. The V1–V3 and V2–V4 face-face dimers bury 266 Å2 and 229 Å2 of surface area, respectively; by comparison, the areas buried by formation of the V1–V2 and V3–V4 back-back dimers are 281 Å2 and 278 Å2, respectively.

The first reported face-face dimer of vancomycin was found in the crystal structure of the vancomycin complex with N-Ac-D-Ala 12. While this structure first suggested the possibility that face-face interactions may contribute to ligand recognition by glycopeptide antibiotics, it differs significantly from the structures that form in the presence of more physiologically relevant ligands. The distance between facing antibiotic molecules is similar in the N-Ac-D-Ala structure and the structures described here; however, in the V2–V4 and V1–V3 face-face dimers, the two facing monomers lie directly opposite one another, whereas the facing monomers in the N-Ac-D-Ala structure are offset with respect to each other, which prevents the two facing ligands from interacting directly. This is not surprising, given that the N-Ac-D-Ala ligand is unable to form the two antiparallel hydrogen bonds that link the tripeptide and longer ligands.

Side-side interactions

In addition to the face-face interactions that link the V1–V2 and V3–V4 dimers, the V5–V6 dimer forms a “side-side” interaction with the other two dimers, making a tight contact with the edge of V2–V4 face-face dimer. This interaction is not ligand-mediated in the way the face-face interaction is, since none of the intermolecular contacts involve ligand atoms. However, in order for this side-side interaction to occur, the ligand-mediated V2–V4 face-face dimer must be in place. Hence, one would not expect the side-side interaction to form in the absence of ligand.

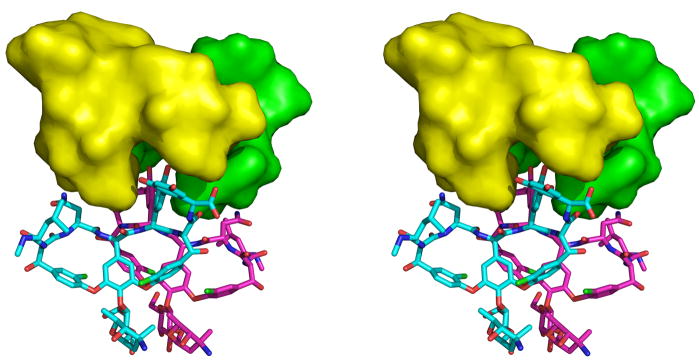

The side-side interaction is mediated by five pairs of hydrogen bonds and an aromatic-amine interaction, as well as by impressive shape complementarity between the V5–V6 back-back dimer and the V2–V4 face-face dimer (Figure 5). The asparagine side chains of V6:3 and V4:3 form a hydrogen bond, as do the asparagine side chains of V5:3 and V2:3. The side chain amino group of V2:3 lies 3.5 Å from the centroid of the aromatic ring of the side chain of V5:5, approaching the ring plane in a nearly perpendicular fashion to form an aromatic-amine interaction 33. Similar interactions occur between V4:3 and V6:5. The phenolic hydroxyl group of V5:5 forms a hydrogen bond with one of the phenolic hydroxyl groups of the resorcinol ring of V2:7. A similar interaction is formed between V6:5 and V4:7. Close hydrogen bonds occur between the C-terminal carboxylate of V6 and the phenolic hydroxyl group of V4:5, as well as between the C-terminus of V5 and V2:5. Finally, weak hydrogen bonds can be seen between the asparagine side chains of V2:3 and V4:3 and the backbone carbonyl oxygens of V5:4 and V6:4 respectively, as well as between the asparagine side chains of V5:3 and V6:3 and the backbone carbonyl oxygens of V2:2 and V4:2, respectively. The surface area buried in the side-side interaction is quite large, 621 Å2, over twice the surface area buried in forming either the face-face or back-back dimers. Approximately half (48%) of the buried area represents buried carbon atoms, and hence is hydrophobic in nature.

Figure 5.

Stereo views of the side-side interaction. a) Hydrogen bonding interactions between V4 (yellow) and V6 (cyan), shown as dashed lines. Similar interactions occur between V2 and V5. The peptide ligands bound to the individual vancomycin monomers are shown in ball-and-stick representation. b) The interaction surface between the V2–V4 face-face dimer and the V5–V6 back-back dimer. V2 and V4 are shown in surface representation, and are colored yellow and green, respectively. The V5 and V6 monomers are shown in a stick representation, and are colored magenta and cyan, respectively. The V2–V4 dimer contains a deep cleft along one side, and the aromatic side chains of residues 5 and 7 of V5 and V6 insert into this cleft. A slightly wider cleft exists between the side chains of residues 3 and 5 of V5 and V6, and the side chains of V2:3 and V4:3 pack into these clefts, respectively.

Oligomer formation in solution

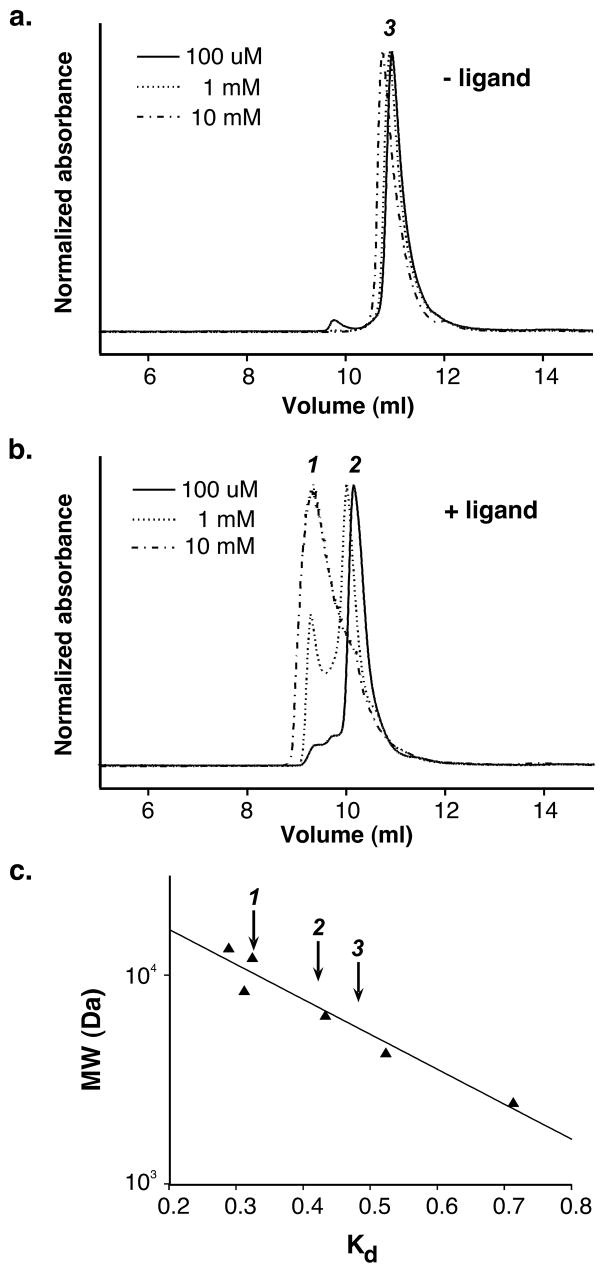

Our first observation suggesting that vancomycin behavior changes upon ligand addition was made during crystallization experiments. Vancomycin and the peptide ligand are both very soluble in water. However, when concentrated aqueous solutions of the two were mixed, the complex precipitated; this same phenomenon has previously been demonstrated by other workers 34. After the structure was determined, the large surface areas buried for the face-face and side-side interactions, along with the fact that highly similar packing arrangements are observed in other vancomycin and balhimycin crystals, led us to test more directly whether ligand-mediated oligomerization of vancomycin occurs in solution. We first used size exclusion chromatography to monitor differences in hydrodynamic radius (Rh) in the presence and absence of the N-Ac-Lys-D-Ala-D-Ala tripeptide ligand (the tripeptide ligand was used because the resulting complex is more soluble than that formed between vancomycin and N-Ac-D-Ala-D-Ala). Vancomycin was preincubated with ligand and then run on a column equilibrated with ligand-containing buffer. In the presence of ligand, vancomycin eluted much earlier than ligand-free vancomycin (Figure 6). Even at the lowest vancomycin concentrations assayed, the apparent hydrodynamic radius is much larger than that observed in the absence of ligand. Increasing vancomycin concentration gives rise to the formation of even larger species. In the absence of ligand, some concentration-dependent increase in Rh is evident, and probably reflects dimerization 35; however, this effect is minor when compared to the effect of ligand addition. Similar changes in hydrodynamic radius were seen with three different chromatographic matrices.

Figure 6.

Size exclusion chromatography reveals an increase in vancomycin hydrodynamic radius in the presence of a tripeptide ligand. a) Chromatograms obtained for three different injected concentrations of vancomycin in the absence of ligand. Species 3 represents the average elution volume for ligand-free vancomycin. b) Chromatograms obtained for three different vancomycin concentrations when the column is pre-equilibrated with 100 μM of the tripeptide ligand. Two species (1 and 2) are seen, with increased vancomycin concentration favoring species 1 over 2. c) Estimation of approximate hydrodynamic radii for the species observed in panels (a) and (b). Kd values for six standard proteins and peptides are shown as triangles, with the line representing the least-squares fit to these points. The arrows mark the Kd values for species 1–3.

It is challenging to estimate the hydrodynamic radii of the vancomycin oligomers from the size exclusion data, since these species fall at the extreme small end of the useful fractionation range for most commercially available matrices. With the caveat that the molecular weight estimates obtained from these experiments should be considered crude approximations, comparison with molecular weight standards suggests a molecular weight for the ligand-free species of approximately 5 kDa (Figure 6), compared to an expected value of 3 kDa for the dimer. The larger species seen in the presence of ligand elute at volumes consistent with molecular weights of 7 and 10 kDa; these values may be compared with calculated molecular weights for tetramers and hexamers of 6 and 9 kDa, respectively.

We used dynamic light scattering to gain an independent assessment of the effect of ligand on vancomycin’s oligomerization state. These measurements yielded estimated Rh values of 1.1 nm in the absence of ligand, increasing to 1.8 nm in the presence of ligand. Both conditions gave unimodal estimated Rh distributions with low-to-modest polydispersity.

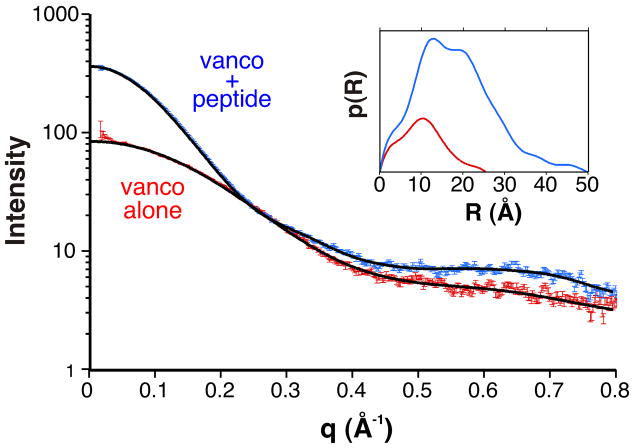

We then turned to small angle X-ray scattering to further characterize the vancomycin-peptide complex. Diffraction measurements were made from concentrated solutions of vancomycin (2.5 mM) in the presence and absence of an excess of the N-Ac-Lys-D-Ala-D-Ala tripeptide ligand. A clear difference in the size of the scattering species could be observed (Figure 7). The radius of gyration estimated from Guinier analysis almost doubled upon addition of the ligand, increasing from 8.2 Å to 14.3 Å. In the presence of the ligand, the I(0) value increased roughly four-fold, also consistent with a large increase in size.

Figure 7.

Small angle X-ray analysis of ligand-mediated vancomyin oligomerization. Scattering curves are shown for vancomycin in the presence (blue) and absence (red) of its tripeptide ligand. Inset: Pair correlation function obtained from GNOMIN fits of the scattering data; blue = vancomycin + ligand, red = vancomycin alone.

Discussion

In the presence of high-affinity ligands, vancomycin and balhimycin crystallize so as to form identical hexameric drug-ligand complexes. These supramolecular complexes are seen in four different crystal forms, none of which share the same space group. Different space groups employ different operators to assemble molecules into three-dimensional lattices, so the occurrence of the same oligomer in different space groups implies that oligomerization is not simply being driven by trivial packing considerations 36. This suggests that the face-face and side-side interactions seen in these crystal structures reflect vancomycin’s intrinsic self-association tendencies, and are not merely crystal packing artifacts. Therefore, we might expect that drug-target interactions would lead to the formation of similar complexes at the site of cell wall biosynthesis.

Various tools have been developed to distinguish genuine macromolecular interactions (i. e., those that occur in solution) from crystal packing artifacts. Many of these applications are limited to interactions involving the twenty commonly occurring L-amino acids, and as such are not applicable to non-protein species such as glycopeptide antibiotics. However, some generally applicable metrics are available. For example, Ponstingl et al. have found that the surface areas buried during the formation of genuine protein-protein oligomers are typically in excess of 800–900 Å2 37, larger than those we see in our structure. However, monomeric vancomycin has only one tenth the mass and one fifth the total surface area of even a small protein (MW 1.45 kDa; surface area 1450 Å2). Krissinel and Henrick have recently pointed out that the appropriate size required to stabilize a protein-protein interface depends on the size of the interacting components; larger species require larger interaction surfaces 38. It therefore seems that a cutoff value of 800–900 Å2 is not an appropriate threshold for significance when considering molecules as small as vancomycin. Indeed, the >600 Å2 contact area of the side-side interaction represents over one quarter of the total surface area of the V5–V6 dimer. When viewed in this light, the interaction appears quite likely to be significant.

Another discriminator is the fBU parameter, which is the fraction of all atoms in the interface that are completely buried. fBU has the advantage of being uncorrelated with the total buried interfacial area 39. Most interfaces arising solely from crystal packing have values of fBU that are less than 0.3, whereas fBU values for genuine oligomeric interfaces typically fall in the range 0.34–0.36 40. Using the program AREAIMOL of the CCP4 suite 41, we calculated an fBU value of 0.44 for the side-side packing interface, well above the significance threshold used to identify genuine interfaces. The back-back dimer interface also gives an fBU value of 0.44, and this interaction is known to occur in solution. Interestingly, the fBU value calculated for the V2–V4 face-face interface is 0.24, substantially lower and more in line with the values associated with weaker (but still specific) interactions such as crystal contacts. However, inspection of the structure of the hexamer suggests that the weaker face-face interaction must occur before the stronger side-side interaction; the binding interface required for the side-side interaction is formed only when two monomer-ligand pairs come together in a face-face interaction.

Focusing on the analogy between the face-face interaction and crystal contacts suggests one possible interpretation for this result. Crystal contacts are specific interactions of relatively low affinity that form when the local concentrations of the interacting partners are high. Similar conditions are expected to exist at the sites where glycopeptide antibiotics such as vancomycin interact with nascent cell wall components. High concentrations of muramyl peptides will recruit vancomycin molecules; these vancomycin-ligand complexes may then interact in a ligand-mediated manner to form face-face complexes. The face-face complexes are probably of relatively low affinity, making them transient in nature. These complexes must adopt a relatively open architecture (reflected by the low fBU value) because the peptide ligands that form much of the interface extend beyond the complex, where they are attached to large external structures (membrane-bound Lipid II or nascent peptidoglycan chains). Steric and entropic considerations will therefore limit the tightness of the face-face interface. However, this interaction (and therefore ligand binding) can be stabilized by the addition of another vancomycin dimer in the side-side interaction. Once the face-face dimer of dimers forms, a docking site for a third dimer is created; the third dimer binds in the relatively tight side-side orientation and thereby stabilizes the face-face interaction.

This speculative model suggests that it should be possible to observe ligand-mediated oligomerization outside of the crystal lattice, in solution. Indeed, using three different biophysical techniques, we have demonstrated that higher order (i.e., larger than dimer) structures do form in the presence, but not the absence, of ligand; the formation of the larger species is concentration-dependent, as predicted. Furthermore, these supramolecular structures form discrete species, and therefore do not merely reflect nonspecific aggregation.

An obvious question is whether the oligomers that form in solution correspond to the structure seen in the crystal asymmetric unit. Molecular weights estimated from size exclusion experiments in the presence of ligand are consistent with the values expected for tetramers and hexamers, while the estimated molecular weight obtained in the absence of ligand is smaller, and more in line with that of the dimer. However, these estimates are subject to significant limitations. Greater precision can be obtained using diffraction methods such as SAXS and DLS. Using the program HYDROPRO 42, we calculated the radius of gyration (Rgyr) and hydrodynamic radius for the unliganded monomer and dimer and for the hexameric vancomycin-ligand complex found in the asymmetric unit . The experimental SAXS and DLS values obtained in the presence of ligand are in excellent agreement with the calculated values obtained for the hexamer (Table 3). Thus, the molecular assemblies seen within the asymmetric unit of our crystals are consistent, in terms of overall size, with the ligand-bound species observed in solution. In the absence of ligand, the experimental values for both Rgyr and Rh lie between the calculated values for monomer and dimer. This might reflect the presence of both species, and indeed the reported dimer association constant 20 of 700 M−1 predicts that roughly equal concentrations of monomer and dimer should be present under the conditions used for our experiments.

Table 3.

Comparison of calculated and observed hydrodynamic parameters

| Calculated Rgyrc (Å) | Calculated Rhc (Å) | |

|---|---|---|

| Monomera | 8.0 | 10.0 |

| Dimera | 9.4 | 12.3 |

| Hexamerb | 14.1 | 17.9 |

| Observed Rgyrd (Å) | Observed Rhe (Å) | |

|

| ||

| Vancomycin minus ligand | 8.2 | 11 |

| Vancomycin plus ligand | 14.3 | 18 |

Monomer and dimer without ligand

Hexamer including ligand

Calculated with HYDROPRO 34

From SAXS

From DLS

The oligomerization behavior of vancomycin may be relevant to its antimicrobial mechanism of action. Vancomycin is expected to recognize two different types of muramyl peptide targets in vivo, those found on Lipid II and those found on nascent peptidoglycan chains. For either target, it is likely that multiple copies of the binding epitope will occur in close proximity to one another. Oligomerization of the drug would represent a way to exploit the multivalency of the ligand so as to increase avidity of binding. This effect has been demonstrated in vitro by Whitesides and colleagues, who showed that recognition of multivalent peptide ligands by multivalent vancomycin species leads to huge increases in association constants relative to the monomeric drug-ligand pair 43.

In order for multivalent drug-ligand complexes to form, a cluster of physically close, uncrosslinked peptides must exist. Solid state NMR measurements of intact Staphylococcus aureus cells have indicated that approximately half (46%) of the peptides present in the cell wall peptidoglycan are uncrosslinked 44. Further, these measurements suggest that the uncrosslinked peptides are not evenly distributed throughout the cell wall, but rather are concentrated at the membrane-proximal side, meaning that clusters of uncrosslinked peptides are likely to be found in this region. Such clusters might represent binding sites for vancomycin oligomers.

A three-dimensional structural model for peptidoglycan has recently become available 45. This model shows a honeycomb structure in which extended, regularly spaced carbohydrate chains run parallel to one another (and presumably perpendicular to the plane of the cell membrane). The pendant muramyl peptides extend perpendicular to the carbohydrate chains, parallel to the plane of the membrane. The carbohydrate chains adopt a helical conformation with three N-acetyl-glucosamine—N-acetyl-vancosamine disaccharide units per turn, imparting a three-fold screw symmetry to the chain. This means that any two adjacent peptides on a given chain extend outward from that chain in directions 120° apart. While recognizing that this model is currently still somewhat speculative, it is interesting to note that the model predicts a concentration of cell wall peptides within the honeycomb mesh that is quite high (tens of millimolar). Steric constraints appear to prevent any two adjacent peptides on the same carbohydrate chain from being bound to a single vancomycin dimer, in either a back-back configuration 14 or a face-face configuration (PJL, unpublished modeling results). However, the perpendicular distance between two neighboring carbohydrate chains is approximately 34–38 Å. Two peptides, one from each neighboring chain, can easily be modeled as spanning this distance and meeting in the middle in an antiparallel β-type pairing such as that seen in the face-face interface. It is also possible to model two such peptides as extending into the space between two carbohydrate chains and being bound to a back-back vancomycin dimer. If a vancomycin dimer (either face-face or back-back) were to bind to such a pair of peptides, then it could serve as a nucleating point for the assembly of a larger complex. The geometry of this peptidoglycan model implies that other, nearby, peptide ligands may participate in such a complex, and that the spacing between neighboring glycan chains is sufficiently large to accommodate tetrameric or hexameric vancomycin assemblies.

Materials and Methods

Crystallization and structure determination

Vancomycin solutions for crystallization were prepared by mixing 40 μl vancomycin stock solution (50 mg/ml in H2O), 50 μl DMSO, 11.2 μl N-acetyl-D-Ala-D-Ala (50 mg/ml in H2O), and 104.4 μl 0.25 M MES, pH 6.0. Crystals were grown at 291 K by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method, mixing 2 μl of the vancomycin crystallization solution with 2 μl of reservoir solution containing PEG 400 + sodium citrate in 0.1 M Tris-Cl, pH 8.5. Crystals were observed in the concentration ranges 30–60% v/v PEG 400 and 0.2–0.4 M sodium citrate. Note that in solutions containing high concentrations of both PEG and sodium citrate, sodium citrate could approach saturation in the reservoir; vancomycin:ligand crystals were sometimes harvested from drops over wells containing sodium citrate crystals. Crystals grew over a period of several weeks to final sizes of approximately 0.15 × 0.15 × 0.4 mm. Crystals were removed from the drop using nylon loops and plunged directly into liquid nitrogen prior to data collection.

Diffraction data were collected at beamlines X8C & X12B of the National Synchrotron Light Source and processed using Denzo/Scalepack 46. Data processing statistics are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics

| Data set | Low energy | High energy |

|---|---|---|

| Beamline | X8C NSLS | X12B NSLS |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.7433 | 0.9780 |

| Data collection temperature | 100 K | 100K |

| Space group | C2221 | C2221 |

| Unit cell (Å) |

a = 66.11, b = 71.89, c = 48.35 |

a = 65.68, b = 71.52, c = 48.37 |

| Number unique reflections | 16,376 | 28,795 |

| Number observations | 124,550 | 141,659 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 25–1.95 (2.03–1.95) | 25–1.30 (1.38–1.30) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.3 (97.9) | 92.2 (66.1) |

| I/σ(I) | 20.6 (10.2) | 29.1 (4.1) |

| Rmerge | 0.067 (0.107) | 0.049 (0.283) |

|

Refinement | ||

| Resolution range (Å) | 25–1.30 | |

| Number of reflections used | 28,795 | |

| Number of antibiotic atoms | 606 | |

| Number of peptide ligand atoms | 84 | |

| Number of solvent atoms | ||

| Water | 167 | |

| MES | 12 | |

| PEG | 112 | |

| Na+ | 1 | |

| Mean B values (Å2) | ||

| antibiotic | 13.3 | |

| ligand | 12.3 | |

| Rcryst/Rfree | 0.172/0.195 | |

Phasing was accomplished by exploiting the anomalous signal of chlorine, using data collected at an X-ray energy of 7.1 keV (wavelength 1.743 Å). The program SnB 47; 48 was used to identify positions of chlorine atoms from the amplitudes of the anomalous differences. The initial SnB run gave a bimodal distribution of solutions. The best solution was analyzed to find groups of four putative chlorine positions that matched the known geometry of the four chlorine atoms in the back-to-back vancomycin dimer 10; 13. In this way it was possible to position two aglycon dimers. The eight chlorine positions from these two dimers were used to calculate solvent-flattened SAD phases with OASIS & DM 49; 50. An anomalous difference Fourier map calculated using these phases revealed the location of three of the four chlorine atoms in the remaining dimer. OASIS was then re-run using all twelve chlorine atom positions. DM was used with the high resolution 12.7 keV data set (wavelength 0.978 Å) to extend the phases to a resolution of 1.3 Å. The resulting map, while noisy, showed many recognizable features, including electron density corresponding to the peptide ligands and the vancomycin sugar residues. The remainder of the model was constructed using iterative cycles of building and refinement. Refinement was carried out using first SHELXL 51, followed by Refmac5 52, using the automated water placement feature of ARP/warp 53. In the latter stages of the refinement anisotropic thermal factors were applied. Refinement details are given in Table 1. The final model has been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre under the deposition number CCDC 704975. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Size exclusion chromatography

A BioSep-SEC-S2000 column (300 × 7.8 mm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) was used. The mobile phase was 0.1 M potassium phosphate pH 6.8, and the flow rate 1 ml/min. Chromatograms were obtained monitoring absorbance at 282 nm. The following standards were used to calibrate the column: Blue dextran (to define excluded volume), RNase A, cytochrome c, ubiquitin, aprotinin, charybdotoxin, endothelin, and acetone (to define included volume). Vancomycin samples were prepared in the mobile phase at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 10 mM; the sample injection volume was 50 μL. For analysis of the vancomycin:peptide complex, the column was pre-equilibrated with 100 μ;M N-acetyl-Lys-D-Ala-D-Ala in 0.1 M potassium phosphate, pH 6.8, and the vancomycin sample that was injected contained a 1.5-fold molar excess of the peptide ligand. Distribution coefficients Kd were calculated using the expression Kd = (Ve – V0)/Vi, where Ve is the elution volume for the species of interest, V0 is the void volume, and Vi is the included volume. Similar ligand-dependent increases in vancomycin’s hydrodynamic radius were also seen with columns packed with Superdex 75 (GE Healthcare) and Macrosphere GPC-60 (Alltech), although no effort was made to construct calibration curves for these other matrices (data not shown).

Dynamic light scattering

DLS data were obtained using a DynaPro Titan light scattering instrument (Wyatt Technology Corporation, Santa Barbara, CA, USA). Autocorrelation functions were measured at 298K and 90° scattering angle, using a laser wavelength of 830 nm. Samples were prepared in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 or 0.1 M potassium phosphate, pH 6.8; similar results were seen with both buffers. Sample concentrations of 2 mM vancomycin ±3 mM N-acetyl-Lys-D-Ala-D-Ala were used. Before analysis, samples were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 20 min and filtered through a 0.2 micron filter directly into the sample cuvette.

Small angle X-ray scattering

Samples were prepared in 0.1 M potassium phosphate, pH 6.8 plus 2 mM EDTA. Sample concentrations of 2.55 mM vancomycin ±3.88 mM N-acetyl-D-Ala-D-Ala were used. X-ray solution scattering measurements were performed at beamline X21 at the National Synchrotron Light Source 54. The X-ray wavelength was 0.925 Å and the sample-detector distance was 0.98 m. These parameters, together with the beam center position, were calibrated with a silver behenate standard. The sample holder was a 1 mm quartz capillary (Hampton Research, Aliso Viejo, CA) that was sealed across the evacuated beam path. Both ends of the capillary were open to allow the sample to flow continuously through so as to minimize radiation damage to the sample. Each measurement required ~30 μl of sample and a 60 s exposure time. After each measurement, the capillary was washed repeatedly with buffer solution and purged with compressed nitrogen. The scattering patterns were collected using a MAR 165 CCD detector (Mar USA, Inc., Evanston, IL). The data were averaged into one-dimensional scattering curves using software developed at the beamline. The scattering from the matching buffer solution was subtracted from the data, based on X-ray transmission data collected simultaneously with each scattering pattern. The program GNOMIN was used to calculate pair correlation distributions p(R) 55.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants GM079508 (PJL) and AI535508 (PHA) from the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Professor Shahriar Mobashery for sharing coordinates of the peptidoglycan model, and Dr. Rod Eckenhoff for access to his light scattering instrument. X-ray diffraction data for this study were measured at the National Synchrotron Light Source. Financial support for this resource comes principally from the Offices of Biological and Environmental Research and of Basic Energy Sciences of the US Department of Energy, and from the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- N-Ac

N-acetyl

- Rgyr

radius of gyration

- Rh

hydrodynamic radius

- RMS

root mean square

- VRE

vancomycin-resistant enterococci

Footnotes

PDB accession numbers 1HHZ and 1GO6 (balhimycin) and 1FVM (vancomycin). In 1HHZ, the asymmetric unit contains three monomers, and the hexameric unit that is homologous with our asymmetric unit is generated by crystal symmetry. In 1GO6, the asymmetric unit contains a fourth dimer, in addition to the three that are homologous with our asymmetric unit. The asymmetric unit in 1FVM is identical to the asymmetric unit in our crystals.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Diekema DJ, BootsMiller BJ, Vaughn TE, Woolson RF, Yankey JW, Ernst EJ, Flach SD, Ward MM, Franciscus CL, Pfaller MA, Doebbeling BN. Antimicrobial resistance trends and outbreak frequency in United States hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:78–85. doi: 10.1086/380457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahne D, Leimkuhler C, Lu W, Walsh C. Glycopeptide and lipoglycopeptide antibiotics. Chem Rev. 2005;105:425–48. doi: 10.1021/cr030103a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Heijenoort J. Formation of the glycan chains in the synthesis of bacterial peptidoglycan. Glycobiology. 2001;11:25R–36R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.3.25r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Heijenoort J. Lipid intermediates in the biosynthesis of bacterial peptidoglycan. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71:620–35. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00016-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goffin C, Ghuysen JM. Multimodular penicillin-binding proteins: an enigmatic family of orthologs and paralogs. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1079–93. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1079-1093.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buynak JD. Cutting and stitching: the cross-linking of peptidoglycan in the assembly of the bacterial cell wall. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:602–5. doi: 10.1021/cb700182u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leimkuhler C, Chen L, Barrett D, Panzone G, Sun B, Falcone B, Oberthur M, Donadio S, Walker S, Kahne D. Differential inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus PBP2 by glycopeptide antibiotics. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3250–1. doi: 10.1021/ja043849e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SJ, Cegelski L, Preobrazhenskaya M, Schaefer J. Structures of Staphylococcus aureus cell-wall complexes with vancomycin, eremomycin, and chloroeremomycin derivatives by 13C{19F} and 15N{19F} rotational-echo double resonance. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5235–50. doi: 10.1021/bi052660s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams DH, Waltho JP. Molecular basis of the activity of antibiotics of the vancomycin group. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:133–141. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90765-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loll PJ, Bevivino AE, Korty BD, Axelsen PH. Simultaneous recognition of a carboxylate-containing ligand and an intramolecular surrogate ligand in the crystal structure of an asymmetric vancomycin dimer. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:1516–1522. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loll PJ, Kaplan J, Selinsky BS, Axelsen PH. Vancomycin binding to low-affinity ligands: Delineating a minimum set of interactions necesary for high-affinity binding. J Med Chem. 1999;42:4714–4719. doi: 10.1021/jm990361t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loll PJ, Miller R, Weeks CM, Axelsen PH. A ligand-mediated dimerization mode for vancomycin. Chem Biol. 1998;5:293–298. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schafer M, Schneider TR, Sheldrick GM. Crystal structure of vancomycin. Structure. 1996;4:1509–1515. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rekharsky M, Hesek D, Lee M, Meroueh SO, Inoue Y, Mobashery S. Thermodynamics of interactions of vancomycin and synthetic surrogates of bacterial cell wall. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7736–7. doi: 10.1021/ja061828+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh CT, Fisher SL, Park IS, Prahalad M, Wu Z. Bacterial resistance to vancomycin: Five genes and one missing hydrogen bond tell the story. Chem Biol. 1996;3:21–28. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Courvalin P. Vancomycin resistance in gram-positive cocci. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42 Suppl 1:S25–34. doi: 10.1086/491711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerhard U, Mackay JP, Maplestone RA, Williams DH. The Role of the Sugar and Chlorine Substituents in the Dimerization of Vancomycin Antibiotics. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:232–237. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackay JP, Gerhard U, Beauregard DA, Maplestone RA, Williams DH. Dissection of the contributions toward dimerization of glycopeptide antibiotics. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:4573–4580. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nieto M, Perkins HR. Physicochemical properties of vancomycin and iodovancomycin and their complexes with diacetyl-L-lysyl-D-alanyl-D-alanine. Biochem J. 1971;123:773–87. doi: 10.1042/bj1230773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams DH, Searle MS, Mackay JP, Gerhard U, Maplestone RA. Toward an estimation of binding constants in aqueous solution: studies of associations of vancomycin group antibiotics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1172–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackay JP, Gerhard U, Beauregard DA, Westwell MS, Searle MS, Williams DH. Glycopeptide antibiotic activity and the possible role of dimerization: A model for biological signaling. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:4581–4590. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li L, Xu B. Multivalent vancomycins and related antibiotics against infectious diseases. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2005;11:3111–3124. doi: 10.2174/1381612054864975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stack DR, Letourneau DL, Mullen DL, Butler TF, Allen NE, Kline AD, Nicas TI, Thompson RC. Covalent glycopeptide dimers: Synthesis, physical characterization, and antibacterial activity. Intersci Conf Antimicr Ag Chemoth. 1998;37:146. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffin JH, Linsell MS, Nodwell MB, Chen Q, Pace JL, Quast KL, Krause KM, Farrington L, Wu TX, Higgins DL, Jenkins TE, Christensen BG, Judice JK. Multivalent drug design. Synthesis and in vitro analysis of an array of vancomycin dimers. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6517–31. doi: 10.1021/ja021273s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sundram UN, Griffin JH. Novel vancomycin dimers with activity against vancomycin-resistant enterococci. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:13107–13108. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicolaou KC, Cho SY, Hughes R, Winssinger N, Smethurst C, Labischinski H, Endermann R. Solid- and solution-phase synthesis of vancomycin and vancomycin analogues with activity against vancomycin-resistant bacteria. Chemistry. 2001;7:3798–823. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010903)7:17<3798::aid-chem3798>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicolaou KC, Hughes R, Cho SY, Winssinger N, Labischinski H, Endermann R. Synthesis and biological evaluation of vancomycin dimers with potent activity against vancomycin-resistant bacteria: target-accelerated combinatorial synthesis. Chemistry. 2001;7:3824–43. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010903)7:17<3824::aid-chem3824>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xing B, Yu CW, Ho PL, Chow KH, Cheung T, Gu H, Cai Z, Xu B. Multivalent antibiotics via metal complexes: potent divalent vancomycins against vancomycin-resistant enterococci. J Med Chem. 2003;46:4904–9. doi: 10.1021/jm030417q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staroske T, Williams DH. Synthesis of covalent head-to-tail dimers of vancomycin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:4917–4920. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lehmann C, Bunkoczi G, Vertesy L, Sheldrick GM. Structures of glycopeptide antibiotics with peptides that model bacterial cell-wall precursors. J Mol Biol. 2002;318:723–32. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loll PJ, Axelsen PH. The structural biology of molecular recognition by vancomycin. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:265–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McPhail D, Cooper A, Freer A. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of a vancomycin-N-acetyl-D-Ala-D-Ala complex. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:534–5. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998011202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burley SK, Petsko GA. Amino-aromatic interactions in proteins. FEBS Lett. 1986;203:139–43. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80730-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McPhail D, Cooper A. Thermodynamics and kinetics of dissociation of ligand-induced dimers of vancomycin antibiotics. J Chem Soc Faraday Trans. 1997;93:2283–2289. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kishimoto K, Manning JM. Adherence of vancomycin to proteins. J Protein Chem. 2001;20:455–61. doi: 10.1023/a:1012527711703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Q, Canutescu AA, Wang G, Shapovalov M, Obradovic Z, Dunbrack RL., Jr Statistical analysis of interface similarity in crystals of homologous proteins. J Mol Biol. 2008;381:487–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ponstingl H, Henrick K, Thornton JM. Discriminating between homodimeric and monomeric proteins in the crystalline state. Proteins. 2000;41:47–57. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20001001)41:1<47::aid-prot80>3.3.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:774–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bahadur RP, Chakrabarti P, Rodier F, Janin J. A dissection of specific and non-specific protein-protein interfaces. J Mol Biol. 2004;336:943–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janin J, Rodier F, Chakrabarti P, Bahadur RP. Macromolecular recognition in the Protein Data Bank. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2007;63:1–8. doi: 10.1107/S090744490603575X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collaborative Computational Project, N. The CCP4 Suite: Programs for Protein Crystallography. Acta Cryst. 1994;D50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia De La Torre J, Huertas ML, Carrasco B. Calculation of hydrodynamic properties of globular proteins from their atomic-level structure. Biophys J. 2000;78:719–30. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76630-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao J, Lahiri J, Isaacs L, Weis RM, Whitesides GM. A trivalent system from vancomycin. D-ala-D-Ala with higher affinity than avidin.biotin. Science. 1998;280:708–11. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cegelski L, Steuber D, Mehta AK, Kulp DW, Axelsen PH, Schaefer J. Conformational and quantitative characterization of oritavancin-peptidoglycan complexes in whole cells of Staphylococcus aureus by in vivo 13C and 15N labeling. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:1253–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meroueh SO, Bencze KZ, Hesek D, Lee M, Fisher JF, Stemmler TL, Mobashery S. Three-dimensional structure of the bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4404–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510182103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Met Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith GD, Nagar B, Rini JM, Hauptman HA, Blessing RH. The use of SnB to determine an anomalous scattering substructure. Acta Cryst. 1998;D54:799–804. doi: 10.1107/s0907444997018805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weeks CM, Miller R. The design and implementation of SnB v2.0. J Appl Cryst. 1999;32:120–124. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cowtan K. ‘dm’: An automated procedure for phase improvement by density modification. Joint CCP4 & ESF-EACBM Newsletter on Protein Crystallography. 1994;31:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hao Q, Gu YX, Zheng CD, Fan HF. OASIS: A computer program for breaking phase ambiguity in one-wavelength anomalous scattering or single isomorphous substitution (replacement) data. J Appl Cryst. 2000;33:980–981. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sheldrick GM, Schneider TM. SHELXL: High resolution refinement. Met Enzymol. 1997;277:319–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–55. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morris RJ, Perrakis A, Lamzin V. ARP/wARP and automatic interpretation of protein electron density maps. Met Enzymol. 2003;374 doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang L. The X21 SAXS instrument at NSLS for studying macromolecular systems. Macromolecular Research. 2005;13:538–541. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Svergun DI. Determination of the regularization parameter in indirect-transform methods using perceptual criteria. J Appl Cryst. 1992;25:495–503. [Google Scholar]