Abstract

PURPOSE:

The Canadian Hypertension Education Program (CHEP) was initiated in 1999 to improve hypertension management in Canada. The objective of the present study was to compare antihypertensive pharmacotherapy in Canada before and after the CHEP.

METHODS:

Data were obtained from the longitudinal National Population Health Surveys, which consisted of five cycles at two-year intervals from 1994 to 2002. Recent hypertensive respondents 20 years of age and older were identified the first time hypertension was reported or treated, and were included in a study population of 1453 newly diagnosed hypertensive patients. Persistence with medication use was assessed in the cycle after the first report of hypertension.

RESULTS:

Antihypertensive medication use within two years of hypertension diagnosis increased with age, from 35% in patients 20 to 39 years of age, to 72.1% in those 80 years of age and older. Antihypertensive medication use increased after the CHEP (from 49.2% to 53.8% of the population), as did the use of multiple antihypertensive medications (from 7.5% to 10.6%). The most commonly used antihypertensive medication for men was angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (beta-blockers were second), but the most common medication for women was diuretics. The overall persistence rate for antihypertensive medication use was 73.2% over two years, which had increased after the CHEP (from 70.4% to 75.4%).

CONCLUSIONS:

The implementation of the CHEP was followed by increased antihypertensive medication use, increased use of multiple antihypertensive medications and improved persistence with medication use. Although causality cannot be established with the design of the present study, improved hypertension management in Canada is heartening. Sex-related differences were observed in prescribed medications, even though clinical guidelines do not differentiate between sexes.

Keywords: Antihypertensive medication, Education, Guidelines, Hypertension, Persistence, Quality of care, Sex-related differences, Trends

Abstract

BUT :

Le Programme d’éducation canadien sur l’hypertension (PECH) a été mis sur pied en 1999 afin d’améliorer la prise en charge de l’hypertension artérielle (HTA) au Canada. La présente étude avait pour but de comparer la pharmacothérapie antihypertensive au Canada, avant et après l’instauration du PECH.

MÉTHODE :

Les données ont été tirées des Enquêtes nationales sur la santé de la population, de type longitudinal, menées en cinq cycles, à deux ans d’intervalle, de 1994 à 2002. Des répondants de 20 ans et plus, chez qui un diagnostic d’HTA avait été posé depuis peu ont été repérés au moment de la première déclaration ou du premier traitement, puis inclus dans une population à l’étude composée de 1453 nouveaux patients hypertendus. Le maintien de la médication a été évalué au cours du cycle suivant la première déclaration d’HTA.

RÉSULTATS :

L’emploi des médicaments antihypertenseurs au cours des deux années suivant la pose du diagnostic augmentait avec l’âge; de 35 % chez les patients âgés de 20 à 39 ans, il est passé à 72,1 % chez les patients âgés de 80 ans et plus. Il en allait de même pour l’utilisation de la médication antihypertensive après la mise en œuvre du PECH (de 49,2 % à 53,8 % de la population) et pour l’association d’antihypertenseurs (de 7,5 % à 10,6 %). Le type d’antihypertenseurs le plus souvent employé chez les hommes était les inhibiteurs de l’enzyme de conversion de l’angiotensine, suivis des bêta-bloquants, tandis que, chez les femmes, c’était les diurétiques. Le taux global de maintien de la médication antihypertensive s’est élevé à 73,2 % sur deux ans, ce qui représente une amélioration (de 70,4 % à 75,4 %) de la situation après l’instauration du PECH.

CONCLUSIONS :

La mise en œuvre du PECH a été suivie d’une augmentation de l’emploi des antihypertenseurs et de leur association ainsi que d’une amélioration du maintien de la médication. Même si on ne peut établir de lien causal à partir du présent type d’étude, il est encourageant de constater une amélioration de la prise en charge de l’HTA, au Canada. Des différences liées au sexe ont été observées en ce qui concerne les médicaments prescrits, bien que le guide de pratique clinique ne fasse pas ce genre de distinction.

High blood pressure is the leading risk factor for death and is estimated to cause 50% of cardiovascular disease cases (1). Approximately 25% of adult Canadians have hypertension, and the likelihood of developing hypertension during an average lifespan is more than 90% (2,3). Considering the close relationship between blood pressure and cardiovascular disease (1,4), it is obvious that hypertension is an important public health issue. Fortunately, both lifestyle alterations and antihypertensive medication are effective mechanisms in reducing blood pressure (5). However, despite effective treatment for hypertension being readily available, treatment and control rates for hypertension are suboptimal, even in Canada and other developed countries (2).

The Canadian Hypertension Education Program (CHEP) is a national program with a mandate to improve the management of hypertension by the extensive dissemination of educational material to health care professionals (6,7). The educational material is based on an annually updated evidence-based recommendations program that began in 1999 (8). Preliminary data from national cross-sectional surveys and a cohort of elderly Ontarians have shown increases in the diagnosis of hypertension and antihypertensive treatment after the CHEP program began (9–12). The objectives of the present study were to examine hypertension drug management in a national cohort of recently diagnosed hypertensive Canadian adults, and to compare antihypertensive pharmacotherapy before and after the start of the CHEP program.

METHODOLOGY

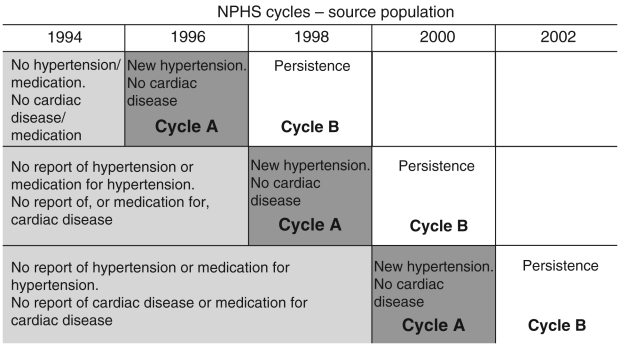

The longitudinal National Population Health Surveys consisted of repeated interviews at two-year intervals between 1994 and 2002 of a sample of the Canadian population. Five interviews were completed for 8198 respondents 20 years of age and older. Among the study population, respondents who were diagnosed with hypertension by a health care professional and/or those who received hypertension medication in one interview cycle (cycle A) without diagnosis or treatment for hypertension in any previous cycle were selected (Figure 1). Persons with pre-existing cardiac disease or those who had undergone treatment for cardiac disease were excluded from the analysis. These newly diagnosed hypertensive respondents were then combined to form a study population of 1453 newly diagnosed hypertensive patients. Persistence with antihypertensive medication use was determined among those taking antihypertensive medication in cycle A by examining antihypertensive drug use in the next cycle (cycle B) two years later (Figure 1).

Figure 1).

Selection of the study population from the source population. A respondent was judged not to have hypertension if it was not reported in the present and previous cycles, if no antihypertensive medication was taken in the past two days in the present and previous cycles, and if there was no reported use of antihypertensive medication or diuretics in the previous 30 days in the present and previous cycles. A respondent was judged to have evidence of hypertension if there was self-reported hypertension, if antihypertensive medication use was reported in the previous two days before the interview, or if there was reported use of antihypertensive medication or diuretics in previous 30 days before the interview. Respondents with heart disease, whether self-reported or taking heart medication, were excluded. NPHS National Population Health Surveys

Information available on each respondent in each cycle included demographic variables, chronic disease and drug use. Self-reported hypertension and heart disease were determined by asking questions about conditions that have lasted, or are expected to last, six months or longer. The most precise drug use data were elicited by the question, “What medications did you take over the last two days?” The respondent was to read the drug name from the label of its container, after which time the drugs were coded using the Anatomic Chemical Therapeutic classification that was developed by the World Health Organization (13) and adapted in Canada (14,15). Information on antihypertensive medication use was also elicited by the question, “In the past month, did you take anything for hypertension, or did you take any diuretics?” Answers to this question were used only to help to identify hypertensive individuals; this was in addition to the questions on self-reported hypertension and antihypertensive medication use two days before the interview.

To assess the impact of the CHEP, the results from two cycles before the start of the CHEP in 1999 (1996 and 1998) were compared with the two cycles following 1999 (2000 and 2002). The source population had been selected as a random sample of the Canadian population, but because of the unique specifications in the selection of the subgroups, statistical weighting for the newly diagnosed hypertensive study group was not considered appropriate.

RESULTS

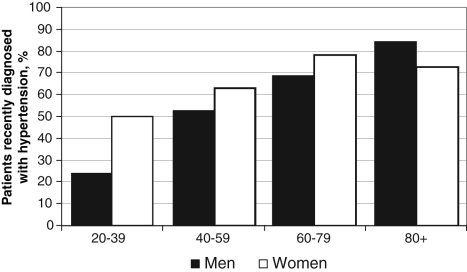

The study population of 1453 individuals recently diagnosed with hypertension included more women than men, and more people younger than 60 years of age than 60 years of age and older (Table 1). On average, 60% of newly diagnosed hypertensive patients took antihypertensive medication, but this proportion varied with age, from 35.0% in those younger than 40 years of age to 72.1% in those 80 years of age and older. In the former age category, considerably more newly diagnosed hypertensive women took antihypertensive medication than men, while in the latter age category, more men took antihypertensive medication than women (Figure 2). After the start of the CHEP, there was an increase in the proportion of newly diagnosed hypertensive patients using antihypertensive medication. Almost 9% of hypertensive patients took more than one type of medication (Table 2), and this proportion increased from 7.5% to 10.6% after the start of the CHEP. Among elderly patients, this increase was especially large; in fact, multiple medication use nearly doubled.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients recently diagnosed as hypertensive

| Patient groups | Time periods

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| All years (1996–2002), n (%) | Before CHEP (1996–1998), n | After CHEP (2000–2002), n | |

| All | 1453 (100.0) | 739 | 714 |

| Men | 618 (42.5) | 318 | 300 |

| Women | 835 (57.5) | 421 | 414 |

| Age younger than 60 years | 872 (60.0) | 443 | 429 |

| Age 60 years and older | 581 (40.0) | 296 | 285 |

CHEP Canadian Hypertension Education Program

Figure 2).

The percentage of recently diagnosed hypertensive patients who were prescribed medication. Medication use was assessed within the two years before diagnosis

TABLE 2.

Number of antihypertensive medications used by recently diagnosed hypertensive patients

| Antihypertensive medications per patient group, n | Time periods

|

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All years (1996–2002), n (%) | Before CHEP (1996–1998), % | After CHEP (2000–2002), % | ||

| All | 1453 | |||

| None | 575 (39.6) | 43.4 | 35.6 | 0.004 |

| One | 747 (51.4) | 49.2 | 53.8 | |

| Two or more | 131 (8.6) | 7.5 | 10.6 | |

| Men | ||||

| None | 260 (42.1) | 46.5 | 37.3 | 0.004 |

| One | 305 (49.4) | 47.5 | 51.3 | |

| Two or more | 53 (8.6) | 6.0 | 11.3 | |

| Women | ||||

| None | 314 (37.7) | 41.0 | 34.3 | 0.060 |

| One | 442 (53.0) | 50.5 | 55.6 | |

| Two or more | 78 (9.4) | 8.6 | 10.1 | |

| Age <60 years | ||||

| None | 377 (46.6) | 51.9 | 40.8 | 0.003 |

| One | 385 (47.5) | 41.6 | 53.7 | |

| Two or more | 49 (5.9) | 6.5 | 5.5 | |

| Age ≥60 years | ||||

| None | 197 (30.7) | 32.4 | 29.0 | 0.019 |

| One | 362 (56.3) | 59.0 | 53.9 | |

| Two or more | 82 (13.0) | 8.6 | 17.0 | |

CHEP Canadian Hypertension Education Program

The use of the different classes of antihypertensive medication is shown in Table 3. The most common classes were angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta-blockers and diuretics, each of which were used by 17% to 19% of the newly diagnosed hypertensive population. Smaller proportions of newly diagnosed hypertensive patients took calcium channel blockers or angiotensin receptors blockers (ARBs). Men and women differed in the use of antihypertensive medication; the most common class for men was ACE inhibitors, followed closely by beta-blockers, while women were much more likely to take diuretics than men (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Antihypertensive medications used by recently diagnosed hypertensive patients

| Time periods

|

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All years (1996–2002), n (%) | Before CHEP (1996–1998), % | After CHEP (2000–2002), % | ||

| Overall | ||||

| All antihypertensive medications | 878 (60.4) | 56.6 | 64.5 | 0.002 |

| ACE inhibitors | 273 (18.8) | 16.1 | 21.6 | 0.008 |

| Beta-blockers | 243 (16.7) | 17.1 | 16.4 | 0.735 |

| Diuretics | 267 (18.4) | 16.9 | 19.9 | 0.144 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 132 (9.1) | 9.6 | 8.5 | 0.481 |

| ARBs | 17 (4.9) | 1.8 | 8.1 | <0.001 |

| Men | ||||

| All antihypertensive medications | 358 (57.9) | 53.5 | 62.7 | 0.021 |

| ACE inhibitors | 129 (20.9) | 17.0 | 25.0 | 0.014 |

| Beta-blockers | 105 (17.0) | 17.0 | 17.0 | 0.995 |

| Diuretics | 84 (13.6) | 11.3 | 16.0 | 0.090 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 52 (8.4) | 9.4 | 7.3 | 0.348 |

| ARBs | 32 (5.2) | 2.2 | 8.3 | <0.001 |

| Women | ||||

| All antihypertensive medications | 520 (62.3) | 58.9 | 65.7 | 0.043 |

| ACE inhibitors | 144 (17.3) | 15.4 | 19.1 | 0.164 |

| Beta-blockers | 138 (16.5) | 17.1 | 15.9 | 0.652 |

| Diuretics | 183 (21.9) | 21.1 | 22.7 | 0.585 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 80 (9.6) | 9.7 | 9.4 | 0.876 |

| ARBs | 39 (4.7) | 1.4 | 8.0 | <0.001 |

| Age <60 years | ||||

| All antihypertensive medications | 434 (53.5) | 48.1 | 59.2 | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitors | 131 (16.2) | 14.0 | 18.4 | 0.090 |

| Beta-blockers | 127 (15.7) | 15.9 | 15.4 | 0.821 |

| Diuretics | 111 (13.7) | 12.1 | 15.4 | 0.173 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 60 (7.4) | 8.0 | 6.8 | 0.525 |

| ARBs | 37 (4.6) | 1.9 | 7.3 | <0.001 |

| Age ≥60 years | ||||

| All antihypertensive medications | 444 (69.7) | 67.6 | 71.0 | 0.353 |

| ACE inhibitors | 142 (22.2) | 18.8 | 25.6 | 0.040 |

| Beta-blockers | 116 (18.1) | 18.5 | 17.7 | 0.779 |

| Diuretics | 156 (24.3) | 23.2 | 25.6 | 0.478 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 72 (11.2) | 11.7 | 10.7 | 0.688 |

| ARBs | 34 (5.3) | 1.5 | 9.2 | <0.001 |

ACE Angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB Angiotensin receptor blocker; CHEP Canadian Hypertension Education Program

The use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs showed significant increases over the study period. ARBs are a newer drug class, introduced in the early years of the present study, and market penetration increased markedly over the years of the study. Table 3 also shows that persons younger than 60 years of age had a greater increase in antihypertensive medication use than those 60 years of age and older, with the greatest change in both age groups being for ARBs. Beta-blockers were used only slightly more often among the elderly patients and showed no increase in either age group.

Overall, persistence with taking antihypertensive medication at least two more years after it was first reported was 73.2% (Table 4). This may refer to the continuous use of the same antihypertensive medication or may include a switch from one antihypertensive medication to another. Persistence with medication use was somewhat higher in men than women –76.7% in men and 70.9% in women – but the difference was not statistically significant. Persistence increased after the start of the CHEP from 70.4% to 75.4% (P<0.001), with the greatest increase in the age group younger than 60 years (P<0.001).

TABLE 4.

Antihypertensive medication persistence*

| n | Still taking medication after two years

|

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All years (1996–2002), % | Before CHEP (1996–1998), % | After CHEP (2000–2002), % | |||

| All | 432 | 73.2 | 70.4 | 75.4 | <0.001 |

| Men | 167 | 76.7 | 73.4 | 79.6 | <0.001 |

| Women | 265 | 70.9 | 68.4 | 73.0 | <0.001 |

| Age <60 years | 210 | 72.9 | 68.8 | 76.1 | <0.001 |

| Age ≥60 years | 222 | 73.4 | 71.8 | 74.8 | <0.001 |

Persistence was defined as taking any antihypertensive medication. CHEP Canadian Hypertension Education Program

DISCUSSION

The present study shows the increased use of antihypertensive medications in a cohort of newly diagnosed hypertensive adults who were representative of the Canadian population. After the initiation of the CHEP in 1999, increases were found in overall antihypertensive medication use, the use of multiple antihypertensive medications and persistence with the use of antihypertensive medication. These results are consistent with the changes in hypertension diagnosis and treatment seen in national cross-sectional studies (9), in increased prescribing of antihypertensive medication for elderly Ontario residents (11) and in increased antihypertensive medication sales in Canada (12). In part, the improved management of hypertension likely explains some of the decrease in cardiovascular disease seen in Canada (16).

A significant question is to what extent the introduction of the Canadian guidelines led to changes. The CHEP started in 1999 with a mandate to improve hypertension management through an extensive health care professional education program based on annually updated evidence-based hypertension recommendations (6,7). Large increases were found in overall antihypertensive medication sales in Canada, as well as for each of class of medication, after the CHEP began (12). Those increases in sales were greater than any of the increases in the present study, possibly because they included total prescription sales over a length of time rather than medication use by newly diagnosed hypertensive individuals. Administrative data for the province of Ontario also showed larger increases in antihypertensive prescriptions than in our study, in part because the Ontario data were limited to the population older than 65 years of age and because the period of assessing antihypertensive drug therapy was longer (11). The present study agreed with other studies on very large increases in the use of ARBs (11,12). The next largest increase was in ACE inhibitor use, which was also the most commonly used initial therapy for the newly diagnosed hypertensive elderly patients in Ontario. Our study found decreases in the use of beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers rather than the increases seen in the commercial sales data from IMS Canada (12). There are differences in the data, in that the IMS data relate to cross-sections of hypertensive patients in the country, while the present study dealt with recently diagnosed hypertensive patients only. Although our study and data from other studies are compatible with improvements in hypertension management after the start of the CHEP, the study design cannot assess causality. System changes to support chronic disease management, as well as local, provincial and other national hypertension programs, may have contributed. However, even though we cannot attribute the improvements to the CHEP with certainty, it is heartening to see that there have been improvements in hypertension management. The cohort design adds to previous evidence by demonstrating that after the CHEP began, there were increases in the treatment of Canadian adults after being diagnosed with hypertension.

The study also found interesting differences between the management of women and men with hypertension. Although Canadian hypertension management recommendations do not differentiate between the sexes (5), there were considerable differences in the types of antihypertensive medication used for men and women, with ACE inhibitors being the most common antihypertensive medication among men and diuretics used more often by women. A rational, scientific basis for these differences is not clear. ACE inhibitors may not be as frequently prescribed in younger women because they are teratogenic (17). Furthermore, men may experience more side effects and less efficacy with diuretics than women compared with ACE inhibitors or beta-blockers (18,19).

Another important aspect of antihypertensive medication use is persistence with its use. The lack of persistence with therapy is a major barrier to blood pressure control (20,21). Our study showed that 73% of patients were still taking antihypertensive medication in cycle B (ie, between two and four years after initial diagnosis), similar to the findings of older Canadian studies (21,22). However, our study also confirmed the interesting findings of Tu et al (10), which showed improvements in persistence with antihypertensive therapy between 1994 and 2003. Improvements in persistence may reflect improved attitudes and knowledge among the public or health care professionals about hypertension, or it may reflect the increased use of newer antihypertensive medications that have higher persistence rates (23,24).

The survey data used had strengths and limitations. Strengths included the longitudinal structure, with interviews at regular intervals, which allowed for the monitoring of hypertension development and of respondent reactions to the diagnosis of hypertension. Extensive questionnaire data were available for each respondent in each cycle, including exact drug use information, which allowed the study to examine the antihypertensive medication classes and the total antihypertensive medication use. Furthermore, the initial cohort was selected to be representative of the Canadian population. There were also features in the present study that may have acted as constraints, such as the definitions of certain key variables. Specifically, there was no measurement of blood pressure, so the definition of hypertension was limited to self-reported hypertension and/or antihypertensive medication use. There was also variation in the length of time for which the respondents were aware of having been diagnosed with hypertension from one cycle to the next. On average, the length of time from diagnosis to the next survey was approximately one year, but this varied from less than a few weeks to almost two years. The length of time from diagnosis very likely affects rates of antihypertensive therapy prescriptions and adherence to therapy. Given the limitation of the timing, we can still conclude that within two years of diagnosis, 64.5% of Canadian hypertensive patients in the present study indicated that they were taking antihypertensive medication.

CONCLUSIONS

While clinical guidelines are important, they are not useful if physicians or patients do not adhere to them. Our study has shown improvements in several aspects of antihypertensive medication use in newly diagnosed hypertensive patients after the implementation of the CHEP, which are all important elements of hypertension management. However, it is likely that a considerable proportion of hypertensive patients still do not have their hypertension managed based on recent guidelines (25). Despite all the publicity on hypertension, misconceptions about the importance of hypertension continue. Only one-half of those with high blood pressure had ever discussed blood pressure with their physicians (26). There still is a great need for public and health care professional education to improve hypertension management (27,28).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: Dr Norm Campbell has received research funds for epidemiological research from Pfizer Canada, sanofi-aventis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Servier Canada and Merck Frosst Canada; travel grants from Servier Canada, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Biovail; and honoraria for speaking from most companies that produce brand name antihypertensive drugs in Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health OrganizationThe world health report 2002 –reducing risks, promoting healthy life. Geneva, Switzerland. <www.who.int/whr/2002/en> (Version current at April 19, 2007).

- 2.Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Banegas JR, et al. Hypertension prevalence and blood pressure levels in 6 European countries, Canada, and the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:2363–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasan RS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, et al. Residual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 2002;287:1003–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.8.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R, Prospective Studies Collaboration Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: A meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies Lancet 20023601903–13.(Erratum in 2003;361:1060). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan NA, McAlister FA, Rabkin SW, et al. Canadian Hypertension Education Program The 2006 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part II – therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:583–93. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70280-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drouin D, Campbell NR, Kaczorowski J. Implementation of recommendations on hypertension: The Canadian Hypertension Education Program. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:595–8. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70281-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McAlister FA. The Canadian Hypertension Education Program – a unique Canadian initiative. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:559–64. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70277-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell NRC, Drouin D, Feldman R. A Brief History of Canadian Hypertension Recommendations. Hypertension Canada. 2005;82:1, 5, 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onysko J, Maxwell C, Eliasziw M, Zhang JX, Johansen H, Campbell NR; Canadian Hypertension Education Program Large increases in hypertension diagnosis and treatment in Canada after a healthcare professional education program. Hypertension. 2006;48:853–60. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000242335.32890.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tu K, Campbell NRC, Duong-Hua M, McAlister FA. Hypertension management in the elderly has improved: Ontario prescribing trends, 1994 to 2002. Hypertension. 2005;45:1113–8. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000164573.01177.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell NR, Tu K, Brant R, Duong-Hua M, McAlister FA, Canadian Hypertension Education Program Outcomes Research Task Force The impact of the Canadian Hypertension Education Program on antihypertensive prescribing trends. Hypertension. 2006;47:22–8. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000196269.98463.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell NRC, McAlister FA, Brant R, et al. Canadian Hypertension Education Process and Evaluation Committee Temporal trends in antihypertensive drug prescriptions in Canada before and after introduction of the Canadian Hypertension Education Program. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1591–7. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200308000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, Nordic Council on Medicines Guidelines for ATC Classification. Oslo, Norway: World Health Organization Collaborating Centre; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patented Medicine Prices Review Board ATC Classification System for Human Medicines. Ottawa: Patented Medicine Prices Review Board; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walop W, Semenchuk M. Coding of drugs used by respondents of the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;9:64–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell NRC, Onysko J, Johansen H, Gao R-N. Changes in cardiovascular deaths and hospitalization in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:425–7. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70929-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman JM. ACE inhibitors and congenital anomalies. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2498–500. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe068089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wing LMH, Reid CM, Ryan P, et al. Second Australian National Blood Pressure Study Group A comparison of outcomes with angiotensin-converting – enzyme inhibitors and diuretics for hypertension in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:583–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MRC trial of treatment of mild hypertension: Principal results. Medical Research Council Working Party. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;291:97–104. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6488.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caro JJ, Salas M, Speckman JL, Raggio G, Jackson JD. Persistence with treatment for hypertension in actual practice. CMAJ. 1999;160:31–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caro JJ, Speckman JL, Salas M, Raggio G, Jackson JD. Effect of initial drug choice on persistence with antihypertensive therapy: The importance of actual practice data. CMAJ. 1999;160:41–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rizzo JA, Simons WR. Variations in compliance among hypertensive patients by drug class: Implications for health care costs. Clin Ther. 1997;19:1446–57. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waeber B, Burnier M. Differential persistence with initial antihypertensive therapies: A clue for understanding the needs of hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1021–2. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000226189.28934.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan N, Chockalingam A, Campbell NRC. Lack of control of high blood pressure and treatment recommendations in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2002;18:657–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrella RJ, Campbell NRC. Awareness and misconception of hypertension in Canada: Results of a national survey. Can J Cardiol. 2005;21:589–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell NR, Petrella R, Kaczorowski J. Public education on hypertension: A new initiative to improve the prevention, treatment and control of hypertension in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:599–603. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70282-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McAlister FA, Wooltorton E, Campbell NR, Canadian Hypertension Education Program The Canadian Hypertension Education Program (CHEP) recommendations: Launching a new series. CMAJ. 2005;173:508–9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]