Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) causes chronic infection in humans leading to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Ribosomal RNA transcription, catalyzed by RNA polymerase I (Pol I), plays a critical role in ribosome biogenesis and changes in Pol I transcription rate are associated with profound alterations in the growth rate of the cell. Because rRNA synthesis is intimately linked to cell growth and frequently up-regulated in many cancers, we hypothesized that HCV might have the ability to activate rRNA synthesis in infected cells. We demonstrate here that rRNA promoter-mediated transcription is significantly (10-12 folds) activated in human liver-derived cells following infection with the type 2 JFH-1 HCV or transfection with the sub-genomic type 1 HCV replicon. Further analysis revealed that HCV non-structural protein 5A (NS5A) was responsible for activation of rRNA transcription. Both the N-terminal amphipathic helix and the polyproline motifs of NS5A appear essential for rRNA transcription activation. The NS5A-dependent activation of rRNA transcription appears to be due to hyperphosphorylation and consequent activation of upstream binding factor (UBF), a Pol I DNA binding transcription factor. We further show that hyperphosphorylation of UBF occurs as a result of up-regulation of both cyclin D1 and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (cdk4) by the HCV NS5A polypeptide. These results suggest that the ER-associated NS5A is able to transduce signals into the nucleoplasm via UBF hyperphosphorylation leading to rRNA transcription activation. These results could, at least in part, explain a mechanism by which HCV contributes to transformation of liver cells.

Introduction

Ribosomal RNA transcription, catalyzed by RNA polymerase I (Pol I), plays a critical role in ribosome biogenesis and changes in Pol I transcription rate are associated with profound alterations in the growth rate of the cell (36). rRNA synthesis is frequently up-regulated in many cancers and transformed cells. This is likely due to the increased demand of ribosome biogenesis required for abnormally high levels of protein synthesis in cells lacking growth control. Alternatively, over expression of rRNA could lead to excess protein synthesis and thus could be an initiating step in tumorigenesis (33). Transcription initiation by human RNA Pol I requires at least two factors in addition to Pol I: the upstream binding factor 1 (UBF1) and a species-specific factor, SL1. UBF1, a sequence specific DNA binding protein, interacts with the template rDNA. UBF is known to activate rDNA transcription by recruiting Pol I to the rDNA promoter, stabilizing binding of SL1, and competing with non-specific DNA binding proteins, such as histone H1 (21). SL1, a protein complex containing the TATA-binding protein (TBP) and three Pol I-specific TBP-associated factors (TAFs) (9), confers promoter specificity. Ribosomal RNA transcription is tightly regulated by cell cycle (40, 41). Both UBF1 and SL1 activities are regulated, at least in part, by phosphorylation during M and G1 phases. At the entry of mitosis, phosphorylation by cdk1/cyclin B leads to inactivation of SL1 and UBF1. As a result of SL1 phosphorylation, the ability of SL1 to interact with UBF is impaired, and Pol I transcription is repressed. In early G1 phase, rDNA transcription remains low although the activity of SL1 has been fully restored by dephosphorylation. UBF1 is activated during G1 progression by phosphorylation of serine 484 by cdk 4/cyclin D1 (42) and serine 388 by cdk2/cyclin E and A (41) resulting in full activation of rRNA transcription.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is an enveloped RNA virus belonging to the flaviviridae family. HCV contains a single-stranded plus polarity RNA genome of approximately 9500 nucleotides (24). Upon entry into cells, the viral RNA is translated into a polyprotein, which is processed into mature viral structural and non-structural proteins by host and viral proteases. The structural proteins include the core (C), envelope proteins E1 and E2, and p7, and the non-structural proteins include NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B. HCV causes chronic infection in a relatively high percentage of infected patients leading to cirrhosis of liver and hepatocellular carcinoma. The effects of HCV proteins on hepatocarcinogenesis have undergone intense investigation during the recent years. These studies have implicated three viral proteins (Core, NS5A, and NS3) in hepatocarconogenesis (20). The involvement of all three proteins have been described as being in control of cell cycle through alteration of or interaction with key cellular regulator proteins such as p53, p21, cyclins as well as transcription factors, proto-oncogenes, and growth factors/ cytokines (20).

Because rRNA transcription is intimately linked to cell growth and frequently up-regulated in transformed cells (46), we hypothesized that HCV might have the ability to activate rRNA synthesis in infected cells. We demonstrate here that transcription from the rRNA promoter is significantly up-regulated in cultured human liver cells following infection with the type 2 JFH-1 HCV or transfection with type 1b HCV replicon. Further analysis revealed that HCV non-structural protein 5A was responsible for stimulation of rRNA transcription. The activation of rRNA transcription appears to be due to stimulation of phosphorylation of upstream binding factor (UBF1) possibly as a result of up-regulation of cyclin D1/cdk4 by the NS5A polypeptide. These results could, at least in part, explain a mechanism by which HCV contributes to transformation of liver cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell cultures and transient transfection

Huh-7, Huh-7.5 and Huh-7.5.1 were maintained in RPMI / DMEM medium with 10% fetal bovine serum or a combination of 5%FBS / 5%NCS with or without Na-pyruvate, respectively. Penicillin-streptomycin was added in the regular medium but not during transfection using low serum opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen). RNA tranfections were performed in presence of DIMRIE-C lipofectant (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Stable cell lines containing full-length and subgenomic replicon (type 1b) were made in Huh-7.5 cells by RNA transfection followed by G418 selection and single colony purification (3, 4).

Plasmids

Plasmids phRR and pT7B were kindly provided by Dr. D. L. Johnson (University of Southern California) (44). pT7B contains the 234 nt T7B fragment (DNA fragment from the T7 bacteriphage B arm) inserted between the Bam H1 and Hind III sites of pGEM vector (Promega). Human ribosomal reporter plasmid phRR contains 1650 bp human rDNA sequence of -150 to +1500 followed by 234 nt T7B DNA fragment at the 3′ end in the pBluescript SK+ (pSK) vector (Stratagene). The plasmid used for expression of 6xhis-NS5A fusion protein in E. coli was constructed by inserting the H77C HCV NS5A encoding cDNA fragment between the EcoR1 and Xho 1 sites of the pET-28a vector (Novagen). The eukaryotic expression plasmid of NS5A was constructed by inserting the NS5A (H77C) cDNA fragment into the EcoR1/Xho1 sites of pcDNA Hismax-4C mammalian expression vector (Invitrogen). The recombinant clones used for expression of mutant (deletions and point mutations) NS5A protein were constructed by PCR amplification using the wt NS5A as a template and gene specific primers. The amplified coding sequences were ligated into pcDNA Hismax-4C vector following standard molecular biology protocols at the EcoR1/Xho1 sites using the appropriate primer pairs. The plasmid pTRI-GAPDH is the antisense control template used to produce probes for GAPDH that serve as internal control in RNase protection assay.

Infection of Huh-7.5 cells with JFH-1 HCV

The Japanese Fulminant Hepatitis type 2a strain JFH-1 clone (pJFH-1) provided by Dr. T. Wakita, Tokyo Mtropoliton Institute, Japan, was used for the generation of the virus in Huh 7.5.1 cells (43). Huh-7.5.1 cells were transfected with in vitro transcribed viral RNA as previously described (43), and supernatants were collected from 10 - 168 h after RNA transfection. The filtered (0.45 μM) supernatants containing the virus (∼2 × 106 ffu/ml) were used for infection of naïve Huh7.5.1 cells. Following 20-72h infection, cells were transfected with the rDNA reporter construct phRR using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Inc.). Transfection was continued for 36-48 hours after which total RNA was isolated from each 6 well plate and analyzed by denaturing formaldehyde 1% Agarose gel electrophoresis followed by Northern hybridization with the T7B in vitro synthesized radiolabeled-RNA probe. The ribosomal reporter RNA used for Northern is tagged at the 3′ end by T7B sequences in order to discriminate between the endogenous rRNA and reporter-driven de novo synthesized rRNA transcript. Viral RNA in infected Huh-7.5.1 cells was detected by semi-quantitative RT-PCR using the NS2-specific forward and reverse primers gacgcacctgtgcacggacag and ggagcttccaccccttggaggtg, respectively. For determination of cyclin D1 and cdk4 induction, cell-free extracts were prepared after 20h post-infection. This was found to be the earliest time point at which both cyclin D1 and cdk4 were induced concomitant with activation of rRNA transcription.

NS5A Mutagenesis

The polyproline motifs (PPM-I, PPM-II and PPM-III) were deleted from the wt NS5A background using appropriate gene specific primers and Stratagene developed QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit’. The PCR-based mutagenesis technology involves the digestion of methylated non-mutated strand with DpnI restriction enzyme after PfuTurbo mediated PCR amplication using mutagenic sequence specific primer pairs. The mutated nicked-circular dsDNA was repaired in vivo in E. coli XL-10 cells after DNA transformation. DNA sequencing was performed to confirm the altered sequences. The triple amino acid changes (Ile-8, Ile-12 and Phe-18 to Asp, Glu and Asp, respectively) in the amphipathic helix (clones AH1-5) of wild-type NS5A harboring plasmid was made using the previously published primer sets (10) using the Stratagene mutagenesis kit. The sequence of the sense strand is 5′TCCGGCTCCTGGCTAAGGGACGACTGGGACTGGGAATGCGAGGTGCTGAGCGACGATAAGACC-3′. The sense primers used for PPC-I, II, III deletion mutagenesis are as follows PPC-I: GACTTTAAGACCTGG CTGAAAGCCGGGATTCCCTTTGTGTCCTGC PPC-II: TGTGGTCCATGGCTGGTCCCCTCCTGTGCCTCCGCCTCG PPC-III: GCTACCACCTCCACGGTCCCCTAAAAAGCGTACGGTGGTCCTCACCG

In vitro transcription

Full-length and sub-genomic replicons of HCV type 1a were generous gifts from Dr. Charles Rice at the Rockefeller University, New York having an adaptive mutation in NS5A (S2204I) (3,4). Plasmid DNAs were transcribed in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase / Promega riboprobe system and purified from Agarose gel. Wild-type type 1a HCV NS5A coding region was also transcribed and purified for in vitro transfection of Huh-7/7.5 cells.

NS5A expression

Bacterial expression and purification of NS5A is supplied in supplementary figure 1.

Antibodies

Monoclonal alpha-actin antibody was purchased from Oncogene Research Products. Polyclonal antibodies to UBF1 (H300), Cdk4 (H-22) and Cdk2 (D-12) and monoclonal Cyclin D1 (H-295), Cyclin E (HE12), and Cyclin A (C-160) antibodies were from Santa Cruz. Monoclonal anti-Cyclin D1 (clone Ab-4) and anti-Cyclin A (clone Ab-5), and polyclonal anti-cyclin D were purchased from Neomarkers Inc and Upstate Biotechnology. Nucleolin mAb (clone 4E2) was purchased from Research Diagnostics Inc. Lamin mAb was from Sigma. Phosphoserine specific mAb (Q5) was purchased from Qiagen and p-UBF (Ser484) specific mAb was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse IgG was used for detection of primary antibody by enhanced chemiluminiscence (Amersham pharmacia Biotech) and secondary goat anti-rabbit HRP labeled IgG was used from Upstate Inc for detection of polyclonal primary antibodies.

RNase Protection assays

RNA was extracted by TRIzol (Gibco) following the protocol provided by the vendor. RNase protection assays were carried out by using the RPAIII™ kit (Ambion) as previously described (44). The isolated RNA (4μg) was hybridized with an excess of 32P labeled anti-sense transcript at 45°C overnight. The anti-sense transcript was generated from pT7B by using the Maxi-script kit (Ambion). pT7B was linearized with EcoR1 and used as a template to make the anti-sense T7B riboprobe. The DNA was transcribed by SP6 RNA polymerase in the presence of α32P-CTP (Sp. Act. >3000Ci/mmole, Perkin Elmer). The riboprobe was treated with DNaseI and ethanol precipitated. The hybridized RNA was digested with 150 μl of a 1:100 dilution of highly concentrated RNaseA/RNaseT1 mixture (250 units/ml RNaseA and 10,000 units/ml RNase T1) at 37°C for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by addition of 250μL of stop buffer and the products were precipitated and re-suspended in 6μl of loading dye and electrophoresed on 5% acrylamide-8M urea denaturing gels. The gels were exposed to X-ray film at -70°C and the autoradiograms quantified by scanning with Image J program.

Northern and Western blot analyses

Total RNA was isolated by TRIzol reagent protocol and Northern blot was performed according to the standard protocol. Radioactive T7B riboprobe (Ambion) and/or DNA probe (random primer labeling kit) was made according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The blots were either scanned from the autoradiogram (ImageJ) or subjected to phosphorimager analysis (ImageQuanta) in Typhoon scanner.

For Western blots, proteins were directly transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes from SDS - gels followed by immunoblotting. Antibody dilutions (200-1000 times) were made according to the manufacturer’s suggestions. Following SDS-PAGE and Western transfer, the membranes were probed with the appropriate monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies in presence of either 3% BSA or 5% milk in PBS-Tween and protein bands subsequently detected by chemiluminiscence assay (Amersham Pharmacia) using Horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG.

Results

Ribosomal RNA synthesis is up-regulated by HCV

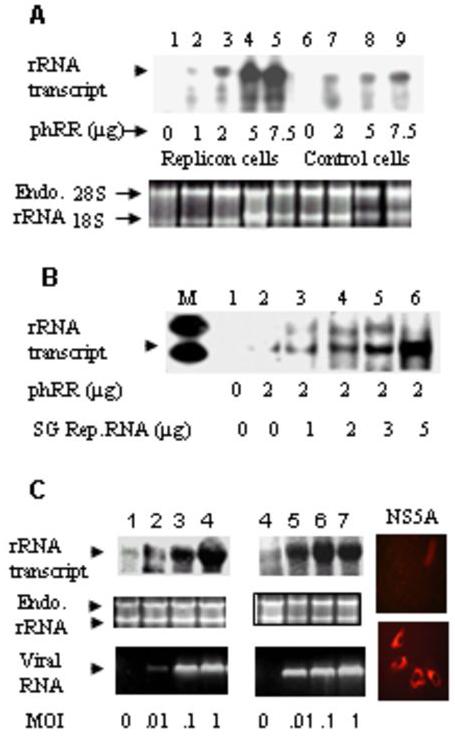

To determine whether HCV is capable of activating rRNA transcription by RNA polymerase I, full-length replicon-harboring cells (4) were transfected with a Pol I reporter construct containing the human Pol I promoter (44). These cells synthesize both viral structural (core, E1, E2, p7) and non-structural proteins (NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A and NS5B).Transcription from the reporter plasmid was monitored by RNase protection assay (44). Accurate initiation from the Pol I promoter produces a 234 nt long product following RNase digestion (44). The appropriate sized RNase-protected transcript was detected at three different concentrations of the rDNA template in control Huh-7 cells (Fig. 1A, lanes 6-9). Ribosomal rDNA transcription was highly stimulated (∼12 fold) in full-length replicon-harboring cells (Fig. 1A, lanes 1-5). To examine if HCV non-structural proteins could stimulate rRNA synthesis in the absence of structural proteins, various amounts of in vitro transcribed HCV subgenomic (SG) replicon RNA (type 1a, NS3-NS5) and the Pol I reporter plasmid were cotransfected into Huh-7 cells, and the de novo synthesized rRNA transcripts were analyzed by RNase protection assay. A titration of SG replicon RNA clearly showed a dose-dependent increase in promoter-mediated transcription with as much as 10 fold increase at the highest concentration of replicon RNA compared to no replicon RNA control (Fig. 1B, lanes 1-6). While our experiments were in progress, the HCV cell culture system using the JFH-1 virus became available (43). In two separate experiments (Fig. 1C, lanes 1-4 and 5-8) infection of Huh-7.5.1 cells with the JFH-1 virus resulted in approximately 10-12 fold stimulation of rRNA synthesis compared to mock-infected cells. These results suggested that HCV could activate rDNA transcription in infected cells.

Fig 1. HCV genomic and sub-genomic replicons and JFH-1 virus activate human ribosomal promoter-mediated reporter transcription in cultured human hepatoma cells.

(A) Stable HCV type 1 full-length replicon (4) and control Huh-7 cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of Pol-I reporter DNA, phRR, as described in Materials and Methods in 60 mm plates at a 60-70% confluency. Total RNA was isolated from each plate after 36h and 4μg RNA was subjected to RNase protection assay (RPA) using [α-32P} labeled T7β RNA as probe. (B) Various amounts of in vitro transcribed HCV type 1 subgenomic replicon RNA (3) were transfected into Huh7.5 cells along with 2 μg Pol I Reporter DNA, phRR. RPA was performed using the total RNA isolated from each 60 mm plate as described above. (C) (Lanes 1-4) Panel I: Huh 7.5.1 cells were infected with JFH1 HCV at various multiplicities of infection as shown. Following 72h infection cells were transfected with the reporter DNA (phRR) for 36 hours. rRNA Northern analysis was performed using the T7β probe using the total RNA (50 μg) isolated from individual six-well plates. Panel II shows endogenous 18S and 28S rRNA as loading controls from the same experiment. Panel III shows RT-PCR analysis of positive strand HCV RNA using NS2 specific primers. Lanes 5-8 show a similar experiment as described for lanes 1-4 except that a different virus preparation was used. Panels IV (preimmune sera) and V (anti-NS5A) show intracellular NS5A expression by immunofluorescence for the experiment described in lanes 1-4.

The HCV NS5A protein upregulates pol I transcription

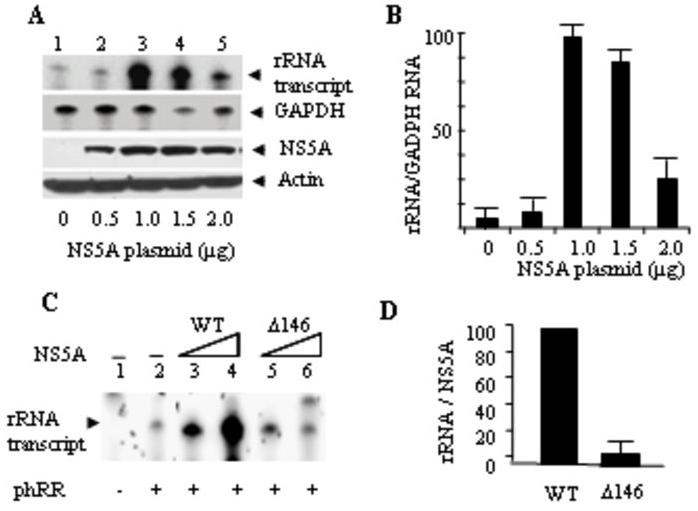

The HCV NS5A polypeptide has been implicated in modulating cell cycle (1, 13, 27). To determine whether the NS5A protein could activate rRNA transcription in the absence of other viral polypeptides, the plasmids encoding the full-length NS5A and the Pol I reporter (phRR) were co-transfected into Huh-7 cells and transcription from the reporter plasmid was examined by RNase protection assay. Transcription from the reporter DNA was stimulated ∼12 fold at 1μg NS5A plasmid compared with the empty vector (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 3, and Fig. 2B). Higher concentrations of NS5A plasmid were found to be inhibitory. NS5A expression as measured by immunoblotting with a polyclonal anti-NS5A antibody was found to be almost saturating at 1μg NS5A-expressing plasmid.

Fig 2. HCV non-structural protein 5A stimulates the ribosomal promoter-mediated reporter transcription in Huh7 cells.

(A) RNAse protection assay (RPA) was performed with total RNA isolated from expression plasmid NS5A DNA-transfected cells (0-2 μg) in 60 mm plates at 70% confluency. GAPDH was used as internal control using the Ambion kit as described in Materials and Methods. Same amount of total RNA was used for detection of both rRNA and GAPDH. NS5A and Actin Western blot analyses were performed from the replica plates using 40 μg of total protein using monoclonal NS5A antibody and β-Actin antibody as internal control. (B) Semi-quantitative estimation of the total rRNA per unit of GAPDH RNA was made by image-scanning of the blots and using the ImageJ software program. (C) Deletion of NS5A N-terminal 146 amino acids results in loss of NS5A-mediated rRNA promoter activation. The RPA assay was used to determine the rRNA transcriptional activation using transient transfections of reporter (2 μg) rDNA templates and NS5A expressing plasmids (0.5 and 1 μg in 60 mm plates for 72 hours) in Huh-7 cells. D. Semi-quantitative estimation of rRNA promoter activity normalized to NS5A (or ΔN146 NS5A) expression by scanning of an immunoblot followed by ImageJ analysis.

Previous studies have shown that a truncated version of NS5A lacking the N-terminal 146 amino acids is a potent activator of RNA polymerase II transcription when fused to the GAL 4 DNA binding domain in both yeast and mammalian cells (12, 39). The full-length NS5A fused to the GAL 4 DNA-binding domain does not activate transcription suggesting interaction with other viral or cellular proteins may be required for its transcriptional activation function. To determine whether the N-terminal 146 amino acids were also dispensable for rRNA transcriptional activation, the N-terminal 146 amino acids of NS5A were deleted, and the effect of the ΔN146 NS5A on rRNA transcription activation was examined. rRNA promoter-mediated transcriptional activation by NS5A was almost totally abrogated by the deletion of the N-terminal 146 amino acids (Fig. 2C-E). Thus, in contrast to Pol II transcriptional activation by NS5A, which required deletion of the N-terminal 146 amino acids, rRNA promoter-mediated Pol I transcriptional activation was dependent on the presence of the NS5A N-terminal 146 amino acids.

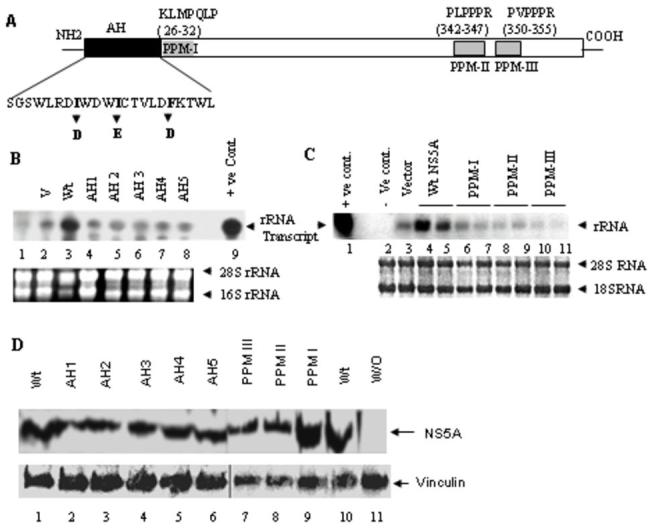

The NS5A N-terminal amphipathic helix and polyproline motifs are important for rRNA transcriptional activation

The N-terminal 30 amino acids of NS5A (Fig. 3A) constitute an amphipathic helix (AH), which appears to be necessary and sufficient for association of NS5A with ER membranes (6). Mutations within the amphipathic helix result in loss of membrane association and viral genome replication (10). In particular, a triple amino acid substitution mutant where isoleucine-8, isoleucine-12, and phenylalanine-19 of the wt NS5A was altered to code for aspartate, glutamate and aspartate, respectively, was completely defective in membrane (ER) association (10). To determine if NS5A membrane association was required for rRNA transcriptional activation, the three mutations (I8D, I12E, and F18D) were introduced into wt NS5A, and the effect of these mutations on rRNA transcription was determined using the Pol I reporter assay. As can be seen in Fig. 3B, all five NS5A clones containing the triple mutations (AH1-5) were highly defective in activating rRNA transcription compared to the wt NS5A. These results suggest that interaction of NS5A with the perinuclear membranes (ER) is important for the NS5A-mediated rRNA transcriptional activation.

Fig 3. NS5A N-terminal amphipathic helix (AH) and polyproline motifs (PPM) are essential for rRNA promoter-mediated transcriptional activation.

(A) Schematic representation of AH and PPM domains of NS5A are shown. Triple substitution mutations (I8D, I12E, and F18D) as shown were engineered into the amino terminal NS5A AH domain as reported previously (10). (B). Five different triple substitution mutant clones (named AH 1-5) were examined for the ability to activate rRNA promoter-mediated transcription in transient transfection assay by trasfecting 1μg wt or mutant NS5A plasmid in 60mm plates for 48h. The rDNA promoter-mediated transcription from the reporter plasmid, phRR, was examined by Northern blot analysis with 50 μg total RNA using the radiolabeled T7β probe as described in Materials and Methods. Endogenous 18S and 28S rRNA were visualized by ethidium bromide staining and served as internal loading control. (C) Polyproline motif deletion constructs (PPM I-III) were used along with the phRR reporter plasmid to determine the role of individual PPMs in rRNA promoter-mediated transcriptional activation under conditions described in panel B. (D) Western blot analysis was performed to detect wt (lanes 1 and 10), AH 1-5 mutants (lanes 2-6) and PPMs I-III mutants (lanes 7-9) expression using a polyclonal anti-NS5A. Vinculin mAb (Sigma) was used to detect Vinculin as internal control. Lane 11 is negative control without (W/O) NS5A expression.

In addition to the amphipathic helix, the NS5A protein contains three polyproline motifs (PPM-I, -II and -III). PPM-I (KLMPQLP) is located immediately following the amphipathic helix, while PPM-II (PLPPPR) and PPM-III (PVPPPR) are located in the C-terminal half of NS5A (Fig. 4A). These motifs are believed to be important for protein-protein interactions through SH3 domains of many signaling proteins (reviewed in ref. 26). To determine if the NS5A polyproline motifs are involved in activation of rRNA transcription, PPM-I, -II and -III were deleted individually and the rRNA transcription activation was determined for each PPM mutant. As can be seen in Fig. 3D, all three NS5A PPM deletion mutants were defective in activating rRNA transcription compared with the wt NS5A. These results suggest that interaction of NS5A with other proteins is important for rRNA transcription activation.

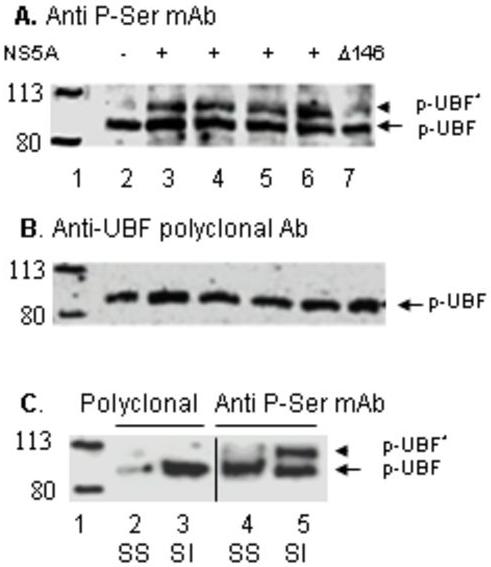

Fig. 4. HCV replicon and NS5A expression induce phosphorylation of UBF in Huh-7.5 cells.

(A) Phospho-UBF1 Western blot. Forty micrograms of total protein from nuclear extracts derived from Huh-7.5 cells transfected with empty vector (lane 2), 1μg wt NS5A DNA (lane 3), 5μg NS5A RNA (lane 4), 7.5μg genomic replicon RNA (lane 5), and 1μg Δ146 NS5A DNA (lane 7) were used for Western analysis using phospho-Ser mAb to detect hyperphosphorylated (pUBF*) and basally phosphorylated UBF1 (pUBF). In lane 6, 40μg of nuclear extract from Huh-7 cells stably transfected with HCV subgenomic replicon was used. Migration of molecular weight marker proteins is shown in lane 1. (B) The panel shows an immunoblot of the same lanes as shown in panel A except that polyclonal anti-UBF1 was used to detect total UBF1 protein.

(C) Huh-7.5 cells were serum-starved (SS) followed by subsequent serum induction (SI). The levels of hyperphosphorylated (pUBF*) and basally phosphorylated UBF1 (pUBF) proteins were determined by Western analysis using phospho-Ser mAB (lanes 4 and 5) and polyclonal anti-UBF1 (lanes 2 and 3). Molecular weight marker proteins are shown in lane 1.

UBF 1 is phosphorylated by NS5A in a manner similar to serum-induced activation of UBF and Pol I transcription

Previous studies have shown that phosphorylation by G1-specific cdk-cyclin complexes at Serine 484 and Serine 388 of UBF activates Pol I transcription during G1 progression (41, 42). To determine whether a similar mechanism is involved in NS5A-mediated activation of Pol I transcription in vivo, phosphorylation of UBF was analyzed in Huh-7 cells following transfection with the wt NS 5A RNA, NS5A DNA, mutant NS5A DNA (ΔN146), and either full-length or subgenomic HCV replicon RNAs. Cell-free extracts were then analyzed by Western blot using a polyclonal antibody to detect NS5A protein level, and a monoclonal phospho-serine antibody that detects phosphorylated forms of UBF (41, 42). The phospho-serine antibody recognizes both the basally phosphorylated (transcriptionally inactive p-UBF) and hyperphosphorylated (transcriptionally active, p-UBF*) proteins. As a positive control, parallel experiments were performed with serum-starved (SS) and serum-induced (SI) Huh-7 cells. The release of liver cells from serum starvation was accompanied by not only an increase in the synthesis of the UBF protein (Fig. 4C, lanes 2 and 3), but also generation of a new phosphorylated UBF (p-UBF*) species detectable by the phospho-Ser antibody (Fig. 4C, lanes 4 and 5). As can be seen in Fig.4A, transfection of cells with DNA or RNA encoding the NS5A as well as HCV full-length or subgenomic replicons resulted in the generation of a similar p-UBF* species observed in serum-stimulated cells (Fig. 4A, lanes 3-6). The intensity of the p-UBF* was significantly lower in cells transfected with the ΔN146 NS5A mutant (Fig. 4A, lane 7) compared with those transfected with the wt NS5A. These results along with the observation that the ΔN146 NS5A mutant was defective in activating Pol I transcription (Fig. 2C) strongly suggest that NS5A-mediated activation of Pol I transcription involves activation of UBF by phosphorylation in a manner similar to that observed during serum-stimulation.

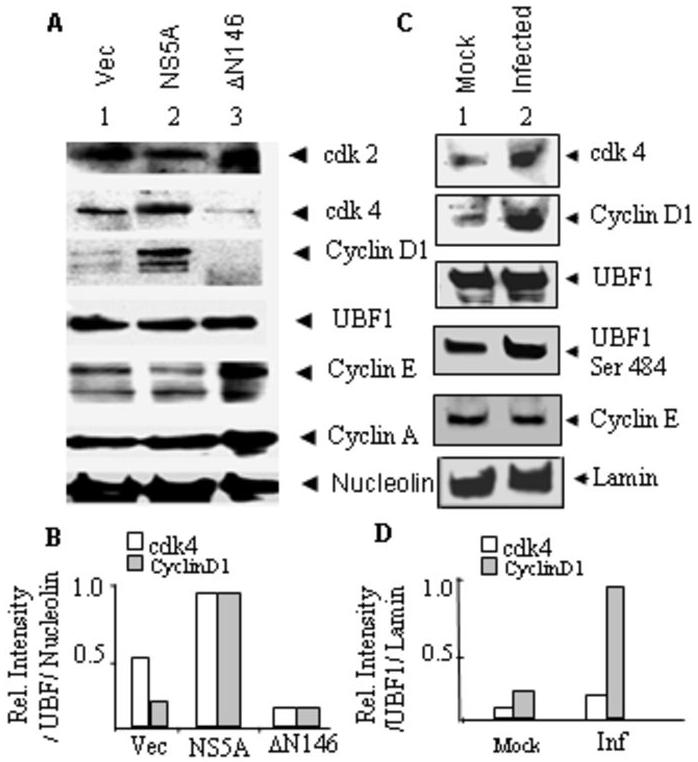

The levels of cyclin D1 and cdk4 in Huh-7 cells are up-regulated by NS5A

UBF is activated during G1 progression by phosphorylation of serine 484 by cdk 4/cyclin D1 and serine 388 by cdk2/cyclin E and A resulting in activation of rRNA transcription. To assess the cdk/cyclin levels in Huh-7 cells expressing the HCV NS5A, Western blots were performed using various antibodies. The levels of both cdk4 and cyclin D1 were significantly elevated in cells transfected with a plasmid encoding NS5A but not the ΔN146 NS5A mutant (Fig. 5A and B). The expression of cyclin D1 and cdk4 appears to be below background level in cells expressing the ΔN146 NS5A mutant protein, as if the mutant is acting in a dominant negative manner. The level of the UBF protein was not changed significantly by NS5A expression compared with the vector alone or ΔN146 NS5A controls. Cdk2 and cyclins A and E levels also did not change significantly by NS5A. These results suggest that NS5A could induce increased expression of cdk4/cyclinD1 in Huh-7 cells. Increased cdk4 expression occurs coincident with over expression of cyclinD1 in many human tumors and tumorigenic mouse models. Some studies suggest that cyclinD1 over expression leads to an increase in cdk4 translation rather than its mRNA level (29).

Fig 5. NS5A expression and JFH-1 virus infection up-regulate CyclinD1 and CDK4 expression.

(A) Huh7.5 cells were transfected with plasmids (1μg each) encoding vector alone, wt NS5A, and ΔN146 NS5A. Cells were harvested after 48 h and nuclear extracts were made for Western analysis using antibodies detailed in Materials and methods. Fifty micrograms of protein was used for the Western analyses. Nucleolin was used as internal control. The expression of the wt and ΔN146 NS5A are shown in supplementary figure 2B. (B) Qantification of the data in figure 5A averaged from two separate experiments. (C) Nuclear extracts (50μg) derived from mock- and JFH1 (moi=1)-infected Huh-7.5.1 cells were used for Western blot analyses using various antibodies as in panel A except that a phosphor-Ser 484 specific UBF1 antibody, which specifically recognizes the phosphor-serine 484 of UBF1 was used (2). Anti-Lamin was used to detect Lamin A in nuclear extract as an internal loading control. (D) Quantification of the data in figure 5C averaged from two separate experiments.

We also compared the levels of cdk4, cyclin D1 and UBF1 between mock- and JFH1-infected cells at a relatively high multiplicity of infection (moi = 1). As can be seen in Fig. 5C and D, the level of cyclin D1 was considerably higher in infected compared to mock-infected cells. Up-regulation of cdk4 was also evident in HCV-infected cells; however, the degree of cdk4 activation was significantly lower in infected cells compared to those transfected with the NS5A plasmid. The cdk4/cyclin D1 complex is known to phosphorylate UBF1 at the ser 484 residue (42). We, therefore, examined UBF1 ser-484 phosphorylation using a monoclonal antibody, which specifically detects ser 484-phosphorylated UBF1 (2). As expected, the intensity of ser 484-phosphorylated UBF1 band was significantly higher (∼2.5 fold) in HCV-infected versus mock-infected cells. The level of the UBF1 protein, however, did not change significantly by infection. We did not detect any significant difference in cyclin E level between mock- and HCV-infected cells. These results suggest that HCV infection of Huh-7.5.1 cells leads to activation of cdk4/cyclinD1, which in turn results in phosphorylation of UBF1 ser 484.

Discussion

Transcription of rRNA genes by RNA polymerase I ultimately determines the number of ribosomes and consequently the potential for cell growth and proliferation in response to changes in the cellular environment including neoplacia. We demonstrate here that HCV, which causes heptocellular carcinoma in chronically infected patients, is able to deregulate rRNA transcription in cultured liver cells. Infection of Huh-7.5.1 cells with the type2 JFH-1 HCV leads to rRNA transcriptional activation (Fig. 1C). This observation is supported by results obtained from Huh-7 cells that stably express and replicate full-length replicon RNA and those that are transiently transfected with RNA encoding only the viral non-structural proteins (sub-genomic replicon) (Fig. 1 A&B). Expression of the HCV NS5A polypeptide in the absence of other viral proteins in Huh-7 cells results in significant stimulation of rRNA transcription (Fig. 2 A&B). Our results are consistent with a number of previously published observations that demonstrated activation of rRNA gene transcription by oncogenic proteins and growth factors that induce cell growth and proliferation (18, 37, 44, 50). The tumor suppressor proteins p53 (47), pRb (7, 40), PTEN (49), and p14ARF (2), on the other hand, have been shown to decrease rRNA gene transcription.

Although the full-length NS5A polypeptide does not enter nucleus, the N-terminal deleted forms containing the nuclear localization signal (NLS) was found to localize to the nucleus (17, 34), suggesting that an altered form of NS5A could act as a potential transcriptional activator in the nucleus. Indeed, previous studies have shown that a truncated version of NS5A lacking the N-terminal 146 amino acids is a potent activator of RNA polymerase II transcription when fused to the GAL 4 DNA binding domain in yeast and mammalian cells (17, 34). Our analysis, however, showed that the N-terminal 146 amino acids of NS5A that contains the N-terminal 30 amino acids long amphipathic helix (AH), was required for activation of rRNA transcription (Fig. 3). The AH has been shown to be required for its interaction with ER membrane. Deletion of the entire amphipathic helix or three point mutations within the AH shown previously to interfere with NS5A membrane binding (10), almost completely abrogated rRNA transcriptional activation by NS5A (Fig. 2C-E, and Fig. 3B). These results suggest that unlike NS5A’s ability to activate Pol II transcription, activation of Pol I transcription requires NS5A-membrane interaction, and that Pol I transcriptional activation may not necessarily require NS5A nuclear entry.

The NS5A N-terminal amino acids 26-32 constitute a class I polyproline motif (KLMPQLP). Two additional closely spaced class II polyproline motifs (aa 342-347 PLPPPR and aa 350-355 PVPPPR) are located near the C-terminus of NS5A. The class II polyproline motifs are able to bind to the SH3 domains of a number of cellular signaling proteins (26). Our results suggest that all three PPMs play important roles in rRNA promoter-dependent transcriptional activation since deletion of each motif results in almost complete lack of rRNA transcriptional activation (Fig. 3D). Taken together, our mutagenesis studies suggest that both NS5A membrane binding and its interaction with other cellular proteins possibly involved in signal transduction are necessary for activation of rRNA transcription.

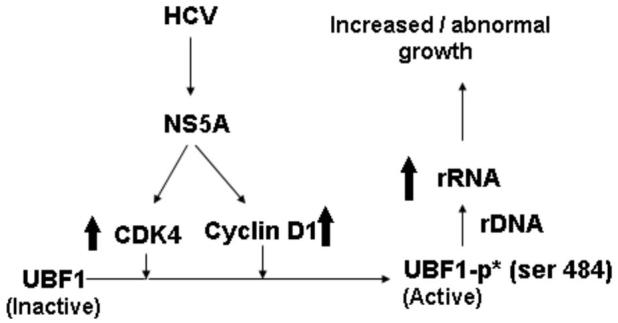

What is the mechanism of RNA Pol I transcription activation by NS5A? Our results clearly show that that expression of NS5A alone in Huh-7 cells is sufficient to generate an additional form of UBF (p-UBF*), which is recognized by a mAb to phosphoserine, suggesting NS5A expression leads to activation of kinase(s) that phosphorylate UBF. This phosphorylation of UBF appears analogous to UBF hyperphosphorylation following serum treatment of serum-starved cells, an event known to activate rRNA transcription. Activation of RNA Pol I transcription during G1 progression has been shown to be mediated by UBF phosphorylation of serine 484 by cdk 4/cyclin D1 (42) and serine 388 by cdk2/cyclin E and A (41). Indeed, the levels of both cyclin D1 and cdk4 are significantly elevated by expression of NS5A in Huh-7 cells or infection of Huh-7.5.1 cells by HCV (Fig. 5). Our observation that cyclin D1 is activated by HCV NS5A is consistent with a previous report that demonstrated activation of cyclin D1 promoter in HCV replicon-bearing cells (45). These results and the fact that UBF1 ser 484 phosphorylation is stimulated by HCV infection (Fig.5C) are consistent with the idea that NS5A is able to activate cdk4/cyclin D1, which results in phosphorylation of UBF at Ser-484 leading to activation of Pol I transcription (Fig. 6). Up-regulation of cyclin D1, a β-catenin regulated gene, could result from activation of Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase and subsequent stabilization of β-catenin following expression of NS5A (38). NS5A-mediated activation of cyclin D1/cdk4 complex and consequent hyperphosphorylation of UBF possibly requires NS5A membrane binding since the ΔN146 mutant fails to activate cyclin D1/cdk4 and promote UBF phosphorylation (Figs. 4 and 5). In fact, the levels of both cyclin D1 and cdk4 appear to be lower in cells expressing ΔN146 NS5A than in vector expressing cells (Fig. 5A) suggesting the N-terminal deletion mutant is acting in a dominant negative manner. This is also supported by the observation that interaction among cyclin D1, cdk4 and UBF1 is drastically reduced in Huh-7.5 cells transfected with the ΔN146 NS5A mutant compared to those that express the wt NS5A (supplemental figure 2). Additionally, for unknown reasons the level of cyclin E appears significantly elevated in ΔN146 NS5A-expressing cells compared to those expressing the wt NS5A protein. The involvement of NS5A has previously been described as being in control of cell cycle through interaction with key cellular regulator proteins such as p53 (27, 32), p21 (1, 13, 22, 32), cdk/cyclins (1, 13, 35) as well as transcription factors (5, 14, 25), proto-oncogenes (14), and growth factors/ cytokines (5, 8, 14, 16, 31).

Fig. 6. Schematic representation of the mechanism by which HCV infection leads to activation of rRNA transcription.

NS5A activates expression of both cyclin D1 and cdk4, which in turn activates transcriptionally inactive UBF1 by phosphorylation of its serine 484 residue. This in turn activates rRNA transcription from rDNA template.

Although results presented here strongly suggest that NS5A-mediated activation of cyclin D1/cdk4 is likely responsible for rRNA transcriptional activation, there are other pathways that could also lead to rRNA transcription activation in HCV-infected cells. For example, it has been reported that Core, NS3 and E2 proteins of HCV can activate the MEK/ERK pathways (23). ERK has been shown to act directly on UBF (37) and transcription intermediary factor (TIF1A) (48) leading to stimulation of rRNA synthesis. In fact, a previous report has suggested that expression of the HCV Core protein activates transcription by all three RNA polymerases (19). However, whether Pol I transcription activation by the Core occurs through cell cycle regulatory kinases was not investigated. It is possible that this functional redundancy (by Core and NS5A) exists to ascertain total deregulation of pol I transcription in HCV-infected cells.

Another potential cellular target that directly modulates rRNA transcription is the retinoblastoma protein (Rb). Rb inhibits Pol I transcription by binding UBF and preventing it from recruiting SL1 (15, 30, 40). Increased production of cyclin D1 in HCV-infected cells could lead to assembly of cyclin D1 into a functional kinase (cdk4 and cdk6) complex, which phosphorylates and inactivates the retinoblastoma protein. This could lead to release of UBF and consequent activation of Pol I transcription. Alternatively, NS5B-dependent ubiquitination of pRb and its subsequent degradation via the proteasome (28) could also lead to UBF release and activation of Pol I transcription. Many other transcription factors, such as Pol II factor E2F, Jun, Ap-2, and Pol III factor TFIIIB are also activated following inactivation of Rb by cyclin D/cdk4 and cyclin D/cdk6 complexes. Thus, transcription of genes by all three classes of RNA polymerases could potentially be activated by elevated levels of cyclin D1.

Amplification or over expression of cyclin D1 plays pivotal roles in the development of human cancers such as parathyroid adenoma, breast cancer, colon cancer, lymphoma, melanoma, and prostate cancer (11). Of the three D-types of cyclins, it is cyclin D1 overexpression that is predominantly associated with human tumorigenesis and cellular metastases. Recent evidence suggests that in addition to its original description as a CDK-dependent regulator of the cell cycle, cyclin D1 also performs cell cycle or CDK-independent functions (11). Cyclin D1 associates with, and regulates activity of transcription factors, co-activators and co-repressors that control histone acetylation and chromatin remodeling proteins. Thus, activation of cyclin D1 in HCV-infected cells could lead to a number of important changes including ribosome biogenesis that ultimately lead to initiation and /or maintenance of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the UCLA Stein Oppenheimer Award and Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center Seed Grant to AD and partially supported by NIH grant AI 72180 and UCLA AIDS grants AI28697 and CC95LA137 to A.D. We are grateful to Dr. T. Wakita for the kind gift of the HCV JFH1 clone, and to Drs. C. Rice and F. Chisari for Huh-7/7.5 and Huh-7.5.1 cells, respectively. We are also grateful to Drs. R. Ray and R.B. Ray (St. Louis University) for the NS5A plasmid. We apologize for not being able to cite many relevant references due to space limitation.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest

None of the authors have any conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Arima N, Kao CY, Licht T, Padmanabhan R, Sasaguri Y, Padmanabhan R. Modulation of cell growth by the hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein NS5A. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12675–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayrault O, Andrique L, Fauvin D, Eymin B, Gazzeri S, Séité P. Human tumor suppressor p14ARF negatively regulates rRNA transcription and inhibits UBF1 transcription factor phosphorylation. 2006;25:7577–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blight KJ, Kolykhalov AA, Rice CM. Efficient initiation of HCV RNA replication in cell culture. Science. 2000;290:1972–74. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5498.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blight KJ, McKeating JA, Marcotrigiano J, Rice CM. Efficient replication of hepatitis C virus RNAs in cell culture. J Virol. 2003;77:3181–90. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.5.3181-3190.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonte D, Francois C, Castelain S, et al. Positive effect of the hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A protein on viral multiplication. Arch Viro. 2004;149:1353–71. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0291-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brass V, et al. An amino-terminal amphipathic alpha-helix mediates membrane association of the hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8130–39. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavanaugh AH, Hempel WM, Taylor LJ, Rogalsky V, Todorov G, Rothblum LI. Activity of RNA polymerase I transcription factor UBF blocked by Rb gene product. Nature. 1995;374:177–80. doi: 10.1038/374177a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi SH, Hwang SB. Modulation of the transforming growth factor-beta signal transduction pathway by hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A protein. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7468–78. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Comai L, Tenese N, Tijian R. The TATA-binding protein and associated factors are integral components of the RNA polymerase I transcription factor, SL1. Cell. 1992;68:965–76. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90039-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elazar M, Cheong KH, Liu P, Greenberg HB, Rice CM, Glenn JS. Amphipathic Helix-Dependent Localization of NS5A Mediates Hepatitis C Virus RNA Replication. J. Virol. 2003;77:6055–61. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.10.6055-6061.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu M, Wang C, Li Z, Sakamaki T, Pestell RG. Minireview: Cyclin D1: Normal and Abnormal Functions. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5439–47. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuma T, Enomoto N, Marumo F, Sato C. Mutations in the interferon-sensitivity determining region of hepatitis C virus and transcriptional activity of the nonstructural region 5A protein. Hepatology. 1998;28:1147–53. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh AK, Steele R, Meyer K, Ray R, Ray RB. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein modulates cell cycle regulatory genes and promotes cell growth. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1179–83. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-5-1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girard S, Vossman E, Misek DE, et al. Hepatitis C virus NS5A-regulated gene expression and signalling revealed via microarray and comparative promoter analyses. Hepatology. 2004;40:708–18. doi: 10.1002/hep.20371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hannan KM, et al. Rb and p130 regulate RNA polymerase I transcription: Rb disrupts the interaction between UBF and SL-1. Oncogene. 2000;19:4988–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He Y, Nakao H, Tan SL, et al. Subversion of cell signalling pathways by hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A protein via interaction with Grb2 and p85 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Virol. 2002;76:9207–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9207-9217.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ide Y, Zhang L, Chen M, Inchauspe G, Bahl C, Sasaguri Y, Padmanabhan Characterization of the nuclear localization signal and subcellular distribution of hepatitis C virus NS5A. Gene. 1996;182:203–11. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00555-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James MJ, Zomerdijk JC. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mTOR signaling pathways regulate RNA polymerase I transcription in response to IGF-1 and nutrients. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:8911–18. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307735200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kao C-F, Chen S-Y, Lee Y-HW. Activation of RNA Polymerase I Transcription by Hepatitis C Virus Core Protein. J. Biomed Sci. 2004;11:72–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02256551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasparzk k, Adamek A. Role of hepatitis C virus proteins in hepatic carcinogenesis. Hepatology Research. 2008;38:1–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuhn A, Grummt I. Dual role of nucleolar transcription factor UBF: transactivator and antirepressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;1992:7340–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lan KH, Sheu ML, Hwang SJ, et al. HCV NS5A interacts with p53 and inhibits p53-mediated apoptosis. Oncogene. 2002;21:4801–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lan-Juan Z, Xiao-Lian Z, Ping Z, Jie C, Ming-Mei C, Shi-Ying Z, Hou-Qi L, Zhong-Tian Q. Up-regulation of ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways by hepatitis C virus E2 envelope protein in human T lymphoma cell line. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2006;80:424–32. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0106014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindenbach BD, Thiel HJ, Rice CM. Flaviviridae: viruses and their replication. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. Lippincott-Raven Publishers; Philadelphia, PA: 2007. pp. 1101–52. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macdonald A, Crowder K, Street A, McCormick C, Saksela K, Harris M. The hepatitis C virus non-structural NS5A protein inhibits activating protein-1 function by perturbing ras-ERK pathway signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17775–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macdonald A, Harris M. Hepatitis C virus NS5A: tales of a promiscuous protein. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:2485–502. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majumder M, Ghosh AK, Steele R, Ray R, Ray RB. Hepatitis C virus NS5A physically associates with p53 and regulates p21/waf1 gene expression in a p53-dependent manner. J. Virol. 2001;75:1401–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1401-1407.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munakata T, Liang Y, Kim S, McGivern DR, Huibregtse J, Nomoto A, Lemon SM. Hepatitis C Virus Induces E6AP-Dependent Degradation of the Retinoblastoma Protein. PLOS Pathogen. 2007;3:1335–47. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parker MA, Deane NG, Thomson EA, Whitehead RH, Mithani SK, Washington MK, Datta PK, Dixon DA, Beauchamp RD. Overexpression of cyclin D1 regulates cdk4 protein synthesis. Cell Prolif. 2003;36:347–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2184.2003.00290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pelletier G, et al. Competitive recruitment of CBP and Rb-HDAC regulates UBF acetylation and ribosomal transcription. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1059–66. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polyak SJ, Khabar KS, Paschal DM, et al. Hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A protein induces interleukin-8, leading to partial inhibition of the interferon-induced antiviral response. J. Virol. 2001;75:6095–106. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.6095-6106.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quadri I, Iwahashi M, Simon F. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein binds TBP and p53, inhibiting their DNA binding and p53 interactions with TBP and ERCC3. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1592:193–204. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rugerro D, Pandolfi PP. Does the ribosome translate Cancer? Nature Reviews. 2003;3:179–92. doi: 10.1038/nrc1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Satoh S, et al. Cleavage of HCV NS5A by a caspase-like protease in mammalian cells. Virology. 2000;270:476–87. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siavoshian S, Abraham JD, Kieny MP, Schuster C. HCV core, NS3, NS5A and NS5B proteins modulate cell proliferation independently from p53 expression in hepatocarcinoma cell lines. Arch Virol. 2004;149:323–36. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sollner-Webb B, Tower J. Transcription of cloned eukaryotic ribosomal RNA genes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1986;55:801–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.004101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stefanovsky VY, Pelletier G, Hannan R, Gagnon-Kugler T, Rothblum LI, Moss T. An immediate response of ribosomal transcription to growth factor stimulation in mammals is mediated by ERK phosphorylation of UBF. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:1063–73. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Street A, Macdonald A, McCormick C, Harris M. Hepatitis C Virus NS5A-Mediated Activation of Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Results in Stabilization of Cellular β-Catenin and Stimulation of β-Catenin-Responsive Transcription. J. Virol. 2005;79:5006–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.5006-5016.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanimoto A, Ide Y, Arima N, Sasaguri Y, Padmanabhan R. The amino terminal deletion mutants of hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein NS5A function as a transcriptional activator in yeast. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;6:360–4. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voit R, Schafer K, Grummt I. Mechanism of repression of RNA polymerase I transcription by the retinoblastoma protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:4230–7. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Voit R, Grummt I. Phosphorylation of UBF at serine 388 is required for interaction with RNA polymerase I and activation of rDNA transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:13631–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231071698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Voit R, Hoffman M, Grummt I. Phosphorylation by G1-specific cdk-cyclin complexes activates the nucleolar transcription factor UBF. EMBO J. 1999;18:1891–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wakita T, et al. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nature Medicine. 2005;11:791–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang H, Trivedi A, Johnson DL. Regulation of RNA Polymerase I-Dependent Promoters by the Hepatitis B Virus X Protein via activated Ras and TATA-Binding Protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:7086–94. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waris G, Turkson J, Hassanein T, Siddiqui A. Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Constitutively Activates STAT-3 via Oxidative Stress: Role of STAT-3 in HCV Replication. J. Virol. 2005;79:1569–80. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1569-1580.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 46.White RJ. RNA polymerases I and III, growth control and cancer. Nature Reviews (Molecular Biology) 2005;6:69–78. doi: 10.1038/nrm1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhai W, Comai L. Repression of RNA polymerase I transcription by the tumor suppressor p53. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:5930–38. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.16.5930-5938.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao J, Yuan X, Frodin M, Grummt I. ERK-dependent phosphorylation of the transcription initiation factor TIF-IA is required for RNA polymerase I transcription and cell growth. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:405–13. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang C, Comai L, Johnson DL. PTEN Represses RNA Polymerase I Transcription by Disrupting the SL1 Complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:6899–911. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.6899-6911.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhong S, Zhang C, Johnson DL. Epidermal growth factor enhances cellular TATA binding protein levels and induces RNA polymerase I- and III-dependent gene activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:5119–29. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5119-5129.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.