Abstract

Objectives

Child maltreatment is associated with multiple adverse developmental outcomes in children. Surprisingly, the most frequently reported perpetrator is the biological mother. Understanding early relationship factors that may help prevent maltreatment is of utmost importance. We explored whether breastfeeding may protect against maternally-perpetrated child maltreatment.

Methods

7223 Australian mother-infant pairs were followed prospectively over 15 years. In 6621 cases (91.7%), the duration of breastfeeding was analyzed with respect to child maltreatment (including neglect, physical abuse and emotional abuse), based on substantiated child protection agency reports. Multinomial logistic regression was used to compare no maltreatment with non-maternal and maternally-perpetrated maltreatment, and to adjust for confounding in 5890 cases with complete data (81.5%). Potential confounders included sociodemographic factors, pregnancy wantedness, substance abuse during pregnancy, postpartum employment, attitudes regarding infant caregiving, and symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Results

Of 512 children with substantiated maltreatment reports, over 60% experienced at least one episode of maternally-perpetrated abuse or neglect (4.3% of cohort). The odds ratio (OR) for maternal maltreatment increased as breastfeeding duration decreased, with the odds of maternal maltreatment in non-breastfed children 4.8 times the odds for children breastfed 4 or more months (95% Confidence Interval [CI] 3.3−6.9). After adjusting for confounding, the odds for non-breastfed infants remained 2.6 times higher (95% CI 1.7−3.9), with no association seen between breastfeeding and non-maternal maltreatment. Maternal neglect was the only maltreatment subtype independently associated with breastfeeding duration (adjusted OR 3.8, 95% CI 2.1−7.0).

Conclusion

Among other factors, breastfeeding may also help to protect against maternally-perpetrated child maltreatment, particularly child neglect.

Keywords: attachment, breastfeeding, child maltreatment, child neglect, mother-child relations, oxytocin

INTRODUCTION

Maltreatment perpetrated by a child's own biological mother represents a fundamental breakdown in the mother-child relationship. Nationwide data in the United States indicate that in almost 60% of substantiated cases, the mother is an identified perpetrator.1 With child maltreatment strongly associated with a range of adverse child outcomes, including impaired emotional and cognitive development,2-4 and increased risk for perpetrating maltreatment in adulthood,5,6 this is cause for significant concern. Understanding which factors may prevent or minimize risk is therefore of critical importance, both in formulating effective intervention strategies for mothers and preventing possible long-term and intergenerational sequelae for children.

The etiology of child maltreatment has been studied extensively over past decades, with multiple risk and protective factors found to act interactively at various levels, from individual parent- and child-related factors, to broader community and societal factors.7,8 Cultural risk factors include a limited social support network, young maternal age, unplanned pregnancy, low education, unemployment and poverty. Parent-related risk factors include anxiety and depression, while prematurity and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit are two child-related factors associated with maltreatment in some studies. Finally, some patterns of early parent-child interaction are also predictive of subsequent maltreatment, such as when there are few expressions of positive affection, less child-focused communication, or more controlling, interfering or hostile interactions.7-9

Human and animal research suggests that early physical contact between a mother and her offspring is important in stimulating and maintaining maternal behavior,10 which may help protect against maternally-perpetrated maltreatment. Breastfeeding may enhance maternal responsiveness by stimulating oxytocin release, which is associated with reduced anxiety and elevated mood, a blunted physiological stress response, and more attuned patterns of maternal behavior—presumably through its central nervous system activity.11-13 A recent report showed that a rise in peripheral oxytocin levels during pregnancy was associated with increased maternal-fetal attachment.14 Another study reported that breastfeeding mothers not only perceived less overall stress, but that breastfeeding, compared with bottle feeding, resulted in a significant reduction in negative mood.15 A mother's response to both child-related and non-child-related stressors may be an important determinant of child maltreatment.16 More long-term associations were seen in a birth cohort of around 1000 mothers and their now-adolescent children, wherein breastfeeding duration was significantly related to the adolescent's positive perception of maternal care received in childhood.17 Finally, simple neonatal procedures which supported breastfeeding and mother-infant contact were associated with decreased rates of infant abandonment in developing countries,18,19 suggesting a link between breastfeeding and reduced child neglect.

We hypothesized that the absence of breastfeeding during the infant's first 6 months of life would independently predict maternally-perpetrated child maltreatment.

METHODS

Study design, setting, and participants

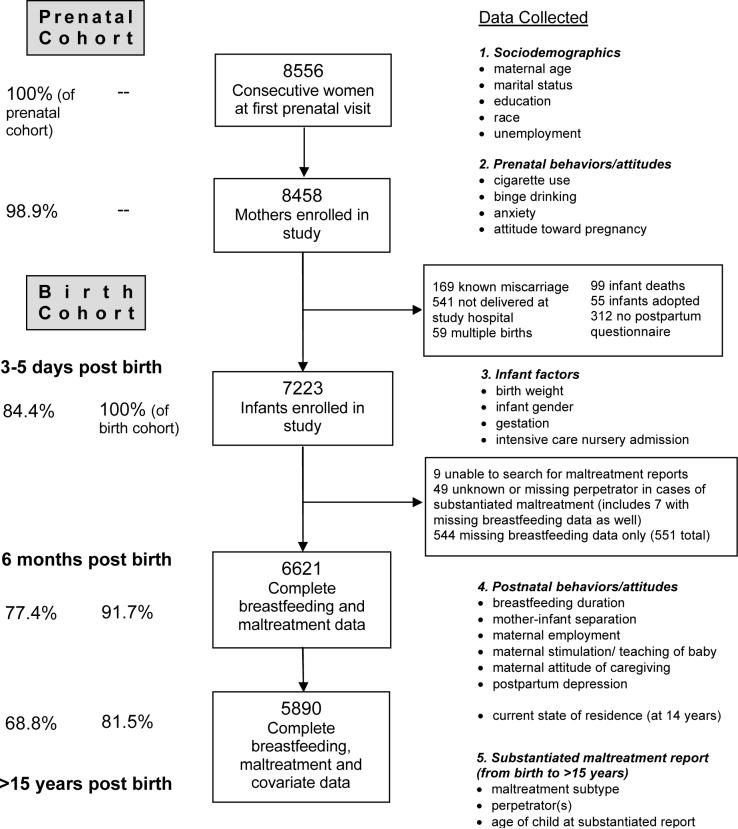

This birth cohort is derived from a longitudinal prenatal cohort of obstetric patients enrolled at a tertiary care maternity hospital in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, between 1981 and 1984.20 Consecutive public patients attending their first prenatal clinic visit were invited to enroll. During these years, a majority of all hospital births (around 60%) were to public patients.20 Data were collected by self-administered questionnaires at three time points: prenatally, 3−5 days postnatally, and at 6-months post-delivery, with informed consent obtained. The birth cohort consisted of children who were live singleton births discharged from the maternity hospital (excluding adopted children), with completed pre- and postnatal questionnaires (Figure 1). The mothers and children were followed over the next 15 to 20 years, and government agency reports of child maltreatment were accessed in September 2000. As this study's hypotheses were not formulated until this time, original data collectors were blind to this study's aims, as well as to each family's maltreatment status.

Figure 1.

Overview of recruitment, follow-up and data collection within the cohort study.

Exposure variable: breastfeeding duration

The key exposure variable was breastfeeding duration, as reported in the 6-month questionnaire. Duration of breastfeeding (full or partial) was recorded in 6 categories: “not at all”, “2 weeks or less”, “3 to 6 weeks”, “7 weeks to 3 months”, “4 to 6 months”, and “still breastfeeding”. As 50% of those reporting “still breastfeeding” responded to their questionnaire between 5 and 6 months, the later 2 categories were combined into “4 or more months”. The remaining 4 categories were combined into: “not breastfed” and “breastfed less than 4 months” to contrast absence of breastfeeding with other categories, and to maximize numbers in each group.

Potential confounding variables

Based on known maltreatment risk factors3,7,8 and breastfeeding predictors,21,22 as well as data available from study questionnaires, 18 potential confounding variables divided into 4 groups, were examined (see Figure 1).

Binge drinking was defined as having 5 or more glasses of alcohol on half or more drinking occasions during pregnancy. Maternal anxiety and depression were determined using standard cut-offs in the short form of the Delusions-Symptoms-States Inventory (DSSI),23 a validated self-report measure. Attitude toward pregnancy was determined from responses to 4 statements about whether the mother planned or wanted to be pregnant at that time, or meant to avoid pregnancy (alpha = 0.89). “Ambivalence” was gauged when the mother predominantly answered “unsure” to these questionnaire items. At around 6 months postpartum, mothers were also asked, “How many hours per week does someone else look after the baby for you?” with 4 possible response categories ranging from “never” to “more than 20 hours per week.” Maternal stimulation/teaching of her baby was based on 4 statements about how often the mother “plays with”, “teaches” or “talks to” her baby (alpha = 0.71). Similarly, maternal caregiving attitude was based on the mother's ratings of 6 statements, examining feelings of satisfaction or frustration in caregiving (“very satisfying” and “my baby is so good” versus “makes me too tired”, “fed up” or “angry”) (alpha = 0.77).

Outcome variable: substantiated child maltreatment

In September 2000, cases of child abuse and neglect investigated by a government child protection agency were accessed and confidentially linked to the longitudinal database. Statewide mandatory reporting laws for medical practitioners were in force during the entire study period. Data confidentiality was preserved using an identification number to anonymously link the 2 databases, as described previously.3,24 Researchers analyzing the maltreatment data had no access to identifying information. Ethical approval for the anonymous database matching was obtained from both the Mater Hospitals’ and University of Queensland ethical review committees.

Cases with suspected child maltreatment were identified from state-based child protection records, along with the date of each episode of substantiated “harm” or “risk”, the subtype(s) of maltreatment reported (neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse and/or sexual abuse), and any identified perpetrator(s). Substantiated maltreatment was determined by child protection case workers who investigated each report of suspected abuse or neglect, where there was “reasonable cause to believe that the child had been, was being, or was likely to be abused or neglected” (i.e. substantiated “harm” or “risk”).25 Childhood neglect was defined as any serious omission of care which jeopardizing or impairing the child's psychological, intellectual or physical development. Physical abuse was defined as any non-accidental physical injury inflicted by a person having care of the child. “Emotional abuse” included attitudes or behaviors directed at a child, leading to impairment of their social, emotional, intellectual or physical development. Finally, the definition of sexual abuse included exposing a child to, or involving a child in, sexual activities inappropriate to the child's age or level of development.25 “Cases” were defined as individual children exposed to abuse or neglect, whereas “episodes” referred to individual occasions of maltreatment. Many cases had multiple episodes recorded over time. Perpetrators listed as “mother” or “both parents” were classified as “maternal” perpetrators, whereas “step mother” and “father's partner” were included in the “non-maternal” maltreatment group (Table 1). Substantiated reports were examined, rather than all suspected maltreatment reports, because perpetrator information was only available for substantiated episodes.

Table 1.

Perpetrators of substantiated maltreatment episodes (for N=512 children).

| Primary Maltreatment Perpetrator |

Substantiated maltreatment episodes |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neglect | Emotional abuse | Physical abuse | Sexual abuse | Any maltreatment | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Biological Mother | 297 (56.1) | 227 (50.0) | 190 (40.9) | 24 (12.1) | 738 (44.8) | |

| Maternal | Biological Mother and Father |

120 (22.7) |

85 (18.7) |

87 (18.8) |

8 (4.0) |

300 (18.2) |

| |

Any Maternal Perpetrator |

417 (78.9) |

312 (68.7) |

277 (59.7) |

32 (16.1) |

1038 (63.0) |

| Biological Father | 48 (9.1) | 81 (17.8) | 104 (22.4) | 54 (27.1) | 287 (17.4) | |

| Step mother / Father's partner | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 6 (0.4) | |

| Step father / Mother's partner | 6 (1.1) | 25 (5.5) | 38 (8.2) | 31 (15.6) | 100 (6.1) | |

| Non-maternal | Other Relative | 7 (1.3) | 6 (1.3) | 7 (1.5) | 25 (12.6) | 45 (2.7) |

| Non-relative |

5 (0.9) |

5 (1.1) |

6 (1.3) |

26 (13.1) |

42 (2.6) |

|

| |

Any Non-maternal Perpetrator |

66 (12.4) |

118 (25.9) |

160 (34.5) |

136 (68.4) |

490 (29.2) |

| Unknown / Missing |

46 (8.7) |

24 (5.3) |

27 (5.8) |

31 (15.6) |

128 (7.8) |

|

| TOTAL | 529 (100) | 454 (100)* | 464 (100) | 199 (100)* | 1646 (100) | |

Sum of percentages does not equal 100 because of rounding.

In order to examine the association between breastfeeding and subsequent maternally-perpetrated maltreatment, each maltreatment episode was categorized by perpetrator (maternal, non-maternal or unknown/missing) (Table 1), and each mother-child pair was classified into one of 3 groups: 1) No substantiated maltreatment of any type, 2) Substantiated maltreatment, with all perpetrators non-maternal, or 3) Substantiated maltreatment, with at least one episode of maternal offence (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of potential confounders by substantiated maltreatment (N=6621).

| N |

Any substantiated maltreatment |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (%) | Non-maternal (%) | Maternal (%) | ||

|

1. Prenatal maternal sociodemographic factors | ||||

| Maternal age (years) | ||||

| 13−19 | 1010 | 88.9 | 2.9 | 8.2 |

| 20−34 | 5308 | 94.8 | 1.7 | 3.5 |

| > 34 | 303 | 96.7 | 2.6 | 0.7 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 5056 | 95.8 | 1.6 | 2.5 |

| Unmarried cohabitation | 714 | 89.5 | 2.4 | 8.1 |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 157 | 86.6 | 3.8 | 9.6 |

| Single | 636 | 86.2 | 3.5 | 10.4 |

| Missing data | 58 | 93.1 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| Education | ||||

| Incomplete high school | 1157 | 89.1 | 3.2 | 7.7 |

| Complete high school | 4227 | 94.4 | 1.9 | 3.7 |

| Post high school | 1196 | 97.3 | 0.8 | 1.8 |

| Missing data | 41 | 92.7 | 4.9 | 2.4 |

| Race | ||||

| Non-aboriginal | 6056 | 94.3 | 1.9 | 3.8 |

| Aboriginal or Pacific Islander | 367 | 88.8 | 2.5 | 8.7 |

| Missing data | 198 | 95.5 | 1.5 | 3.0 |

| Unemployment (either partner) | ||||

| Not unemployed | 5409 | 95.4 | 1.6 | 2.9 |

| Unemployed | 1116 | 87.5 | 3.4 | 9.1 |

| Missing data |

96 |

87.5 |

3.1 |

9.4 |

|

2. Prenatal maternal behaviors/attitudes | ||||

| Cigarette use in early pregnancy | ||||

| Nil | 4123 | 95.6 | 1.5 | 2.9 |

| Light smokers | 1904 | 91.9 | 2.6 | 5.6 |

| Heavy smokers | 527 | 88.8 | 3.2 | 8.0 |

| Missing data | 67 | 95.5 | 0 | 4.5 |

| Binge drinking in pregnancy | ||||

| Never or occasional | 6344 | 94.3 | 1.9 | 3.8 |

| More than half times | 201 | 85.1 | 3.0 | 11.9 |

| Missing data | 76 | 90.8 | 1.3 | 7.9 |

| Anxiety symptoms in pregnancy | ||||

| Not anxious | 5627 | 94.7 | 1.8 | 3.5 |

| Anxious | 813 | 88.9 | 2.8 | 8.2 |

| Missing data | 181 | 95.6 | 1.7 | 2.8 |

| Attitude toward pregnancy | ||||

| Unsure | 1649 | 92.0 | 2.2 | 5.8 |

| Wanted | 3564 | 94.9 | 1.9 | 3.3 |

| Unplanned/unwanted | 1249 | 94.2 | 1.8 | 3.9 |

| Missing data |

159 |

93.1 |

2.5 |

4.4 |

|

3. Infant factors | ||||

| Birth weight (kg) (mean ± SD) | 6620 | 3.40 ± 0.51 | 3.28 ± 0.53 | 3.29 ± 0.57 |

| Infant gender | ||||

| Female | 3172 | 93.5 | 2.2 | 4.3 |

| Male | 3449 | 94.4 | 1.7 | 3.9 |

| Gestation | ||||

| Term | 6356 | 94.2 | 1.9 | 3.9 |

| Preterm (<37 weeks gestation) | 265 | 89.4 | 3.0 | 7.5 |

| Intensive care nursery admission | ||||

| No admission | 6154 | 94.2 | 1.9 | 3.9 |

| Admission | 464 | 90.9 | 2.4 | 6.7 |

| Missing data |

3 |

100.0 |

0 |

0 |

|

4. Post birth maternal behaviors/attitudes (6 months) | ||||

| Mother-infant separation | ||||

| >20 hours/week | 232 | 89.2 | 3.0 | 7.8 |

| 5−20 hours/week | 610 | 92.1 | 2.5 | 5.4 |

| <4 hours/week | 2495 | 94.0 | 1.8 | 4.2 |

| Never | 3263 | 94.8 | 1.9 | 3.3 |

| Missing data | 21 | 81.0 | 0 | 19.0 |

| Maternal employment | ||||

| Homemaker | 4892 | 95.0 | 1.8 | 3.1 |

| Part-time or self-employed | 591 | 95.8 | 1.0 | 3.2 |

| Full-time employed | 212 | 92.0 | 3.3 | 4.7 |

| Other (pension, student, unemployed) | 877 | 87.7 | 3.0 | 9.4 |

| Missing data | 49 | 91.8 | 0 | 8.2 |

| Maternal stimulation/teaching of baby | ||||

| Not always | 965 | 93.8 | 2.1 | 4.1 |

| Always | 5639 | 94.0 | 1.9 | 4.1 |

| Missing data | 17 | 100.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Positive about caring for baby | ||||

| Not always | 395 | 92.7 | 1.8 | 5.6 |

| Mostly | 3643 | 93.7 | 2.2 | 4.1 |

| Always | 2567 | 94.6 | 1.6 | 3.7 |

| Missing data | 16 | 100.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Depression | ||||

| Not depressed | 6288 | 94.3 | 1.8 | 3.9 |

| Depressed | 308 | 88.6 | 4.2 | 7.1 |

| Missing data | 25 | 92.0 | 0 | 8.0 |

Specific subtypes of maltreatment, such as neglect, were similarly defined: 1) No substantiated neglect (but which may have included other types of substantiated maternal or non-maternal maltreatment), 2) Substantiated neglect, with all perpetrators of neglect being non-maternal, or 3) At least one episode of substantiated maternally-perpetrated neglect. Other variables were likewise created for emotional abuse and physical abuse.

With regard to sexual abuse, the mother was listed as a perpetrator in 32 of 199 substantiated episodes (Table 2). However, in all of these cases either an additional male perpetrator was listed (e.g. father, partner, etc) (N=24), the report was for substantiated sexual abuse “risk” rather than “harm” (N=4), or other maltreatment subtypes were listed concurrently (N=4), e.g. maternal neglect and sexual abuse. Since it is unclear whether the mother was the actual perpetrator of sexual abuse in these cases, sexual abuse was not examined as a separate maltreatment subtype. However, with the mother specifically identified as a perpetrator in these substantiated reports, the cases were still included in the variable “any substantiated maternal maltreatment”.

Statistical analyses

The influence of multiple confounding variables was first tested within the four separate variable groups listed in Table 2. All variables in a group were simultaneously entered into a multinomial regression model. Variables from each group that remained significant at P<0.2 were included in the final model. This approach was then repeated with each maltreatment subtype (neglect, emotional abuse and physical abuse) as the dependent variable. As a result of this process, the only variables excluded from the overall model were pregnancy gestation and intensive care nursery admission.

Multinomial logistic regression was used to compare associations between breastfeeding duration, confounding variables and the different maltreatment categories – no maltreatment, non-maternal maltreatment and maternal maltreatment. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each level of breastfeeding duration, and for each potential confounding variable. Adjusted odds ratios were obtained by including previously described potential confounders in a backward regression model, with variables with a statistical significance of P>0.2 being withdrawn in a stepwise fashion. Then, in additional post-hoc analyses, the independent association between predictor variables and specific types of maltreatment (neglect, emotional abuse and physical abuse) was similarly examined. Maltreatment subtypes were added to the final regression models, e.g. substantiated neglect was adjusted for concurrent emotional and physical abuse episodes.

Additional sensitivity analyses were performed: 1) comparing results for children with a mean age of substantiated maltreatment less than or greater than 5 years, 2) comparing children with single vs. multiple episodes of maltreatment, 3) excluding siblings of previously enrolled children from the dataset (520 or 7.2% of the birth cohort), and 4) including only those families who were known to be living in the state of Queensland at age 14 years.

Finally, to assess whether those participants who were excluded in the final analysis because of missing data produced bias in the results, we applied inverse probability weighting to the included subjects to restore the representation of subjects excluded or lost to follow-up.26

A 2-tailed P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (version 15) and STATA.

RESULTS

Study population

Of the 8556 consecutive public patients who attended their first prenatal clinic visit, 98.9% enrolled in the study and completed the first prenatal questionnaire (mean gestation 20±6 weeks). The birth cohort consisted of 7223 children, 52% of whom were male, and 96% delivered at full term (see Figure 1 for those not included). The mean age of the cohort mothers at study entry was 25±5 years, with 75% married, 12% in cohabiting relationships, and 10% single. Eighty-seven percent of mothers were of Caucasian background, 6% were Aboriginal or Pacific Islander and 4% Asian.

The study group was defined as those children with complete breastfeeding and maltreatment data (N=6621, 91.7% of birth cohort). Maltreatment records were not accessed for 8 families because of missing contact details needed for matching, and one family was inadvertently omitted. Cases in which maternal maltreatment could not be ruled out, such as when the perpetrator was unknown or missing, were excluded from all analyses (N=49). An additional 544 children were excluded because of missing breastfeeding data.

Complete breastfeeding, maltreatment and confounding variable data were available for 5890 children (81.5% of birth cohort) (Figure 1).

Maltreatment reports

From the birth cohort of 7223 children, 780 children (10.8%) were reported to Child Protective Services between 1981 and 2000 for suspected child abuse or neglect, and 512 children (7.1%) had at least one substantiated maltreatment episode. Substantiated neglect was reported in 271 cases (3.8%), emotional abuse in 268 cases (3.7%), physical abuse in 286 cases (4.0%), and sexual abuse in 146 cases (2.0%).

In over 60% of children with substantiated maltreatment, there were one or more episodes of maternally-perpetrated abuse or neglect (313 cases; 4.3% of birth cohort), often involving multiple types of maltreatment concurrently. Almost half of the children with substantiated maltreatment had multiple substantiated episodes (N=241 children, with a range of 2−14 episodes per child; median=3). Overall, there were 1646 episodes of substantiated maltreatment, of which almost two-thirds involved the biological mother as a primary perpetrator (N=1038) and over 40% of these were for child neglect (N=417) (Table 1). The biological mother was the most frequently identified perpetrator of substantiated neglect (noted in 79% of neglect episodes), emotional abuse (69%) and physical abuse (60%), whereas the biological father was the most frequent perpetrator of sexual abuse.

Breastfeeding and maternal maltreatment

The relationship between confounding variables and substantiated maltreatment is shown in Table 2. The only variables that were not statistically associated with “any maltreatment” were infant gender and maternal attitudes regarding infant stimulation/teaching and caregiving. All variables except infant gender were also statistically associated with breastfeeding duration, although the strengths of these associations were modest (Spearman correlation coefficients for continuous, dichotomous and ordinal variables, rs ≤0.2). Likewise, there was only a modest correlation between potential confounding variables.

The prevalence of breastfeeding, with respect to substantiated maternal and non-maternal maltreatment is shown in Table 3. Forty percent of cohort children were breastfed for “4 or more months” and 39% for “less than 4 months”, while only 21% were not breastfed at all. An inverse relationship between breastfeeding duration and maternally-perpetrated maltreatment was seen. The prevalence of maternal maltreatment increased as the duration of breastfeeding decreased, when examining all maltreatment subtypes separately or combined. In contrast, children with no substantiated maltreatment were more often breastfed for 4 or more months.

Table 3.

Prevalence (%) of substantiated maltreatment and its subtypes by breastfeeding duration (N=6621).

| Breastfeeding duration | N (%) |

Substantiated maltreatment type |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Neglect (%) |

Emotional abuse (%) |

Physical abuse (%) |

Any maltreatment (%) |

||||||||||

| None | Non-maternal | Maternal | None | Non-maternal | Maternal | None | Non-maternal | Maternal | None | Non-maternal | Maternal | ||

| 4 or more months | 2616 | 98.8 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 98.2 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 98.4 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 97.0 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| (40) | |||||||||||||

| Less than 4 months | 2584 | 96.4 | 0.3 | 3.3 | 96.3 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 96.0 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 92.8 | 2.4 | 4.8 |

| (39) | |||||||||||||

| Not at all | 1421 | 93.6 |

0.7 |

5.7 |

94.5 |

1.2 |

4.3 |

94.7 |

1.8 |

3.6 |

90.6 |

2.3 |

7.2 |

| |

(21) |

||||||||||||

| Total N | 6621 | 6406 | 25 | 190 | 6402 | 61 | 158 | 6399 | 81 | 141 | 6223 | 129 | 269 |

| 100 | |||||||||||||

In an unadjusted analysis of the N=6621 group, the odds of non-breastfed infants being maltreated by their mothers was 4.8 times that of infants breastfed 4 or more months (95% CI 3.3−6.9). However, the highest unadjusted OR was seen for maternal neglect (OR 6.6, 95% CI 4.1−10.4).

Although breastfeeding duration was also associated with non-maternal maltreatment (physical abuse in particular), only maternally-perpetrated maltreatment remained significant after adjusting for confounding (Table 4). For example, in non-breastfed children, the adjusted OR for maternally-perpetrated maltreatment was 2.6 (95% CI 1.7−3.9), compared to 1.1 (95% CI 0.6−1.9) for non-maternal maltreatment (Model Chi-Square=252.8, df=24, P<0.001). Other variables that were independently associated with maternal maltreatment included unmarried status, low maternal education, prenatal unemployment, smoking or binge drinking in pregnancy, prenatal anxiety symptoms and mother-infant separation at 6 months postpartum (Table 5).

Table 4. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for substantiated maltreatment according to breastfeeding duration (N=5890).

Statistically significant results are shown in bold type.

| Breastfeeding duration |

Substantiated maltreatment |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI)* |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) (including maltreatment subtypes†) |

|||||||

| None | Non-Maternal | Maternal | None | Non-Maternal | Maternal | None | Non-Maternal | Maternal | |

|

Any maltreatment | |||||||||

| 4 or more mths | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Less than 4 mths | 1.0 | 1.8 (1.2−2.8) | 3.0 (2.1−4.4) | 1.0 | 1.4 (0.9−2.2) | 2.2 (1.5−3.2) | |||

| Not at all |

1.0 |

1.7 (1.0−2.8) |

4.5 (3.0−6.6) |

1.0 |

1.1 (0.6−1.9) |

2.6 (1.7−3.9) |

|||

|

Neglect | |||||||||

| 4 or more mths | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Less than 4 mths | 1.0 | 0.9 (0.3−2.6) | 3.4 (2.1−5.6) | 1.0 | 0.8 (0.3−2.4) | 2.5 (1.5−4.0) | 1.0 | 0.7 (0.3−2.1) | 2.3 (1.3−4.2) |

| Not at all |

1.0 |

2.3 (0.9−6.0) |

6.5 (4.0−10.5) |

1.0 |

1.9 (0.7−5.3) |

3.8 (2.3−6.2) |

1.0 |

1.6 (0.6−4.6) |

3.8 (2.1−7.0) |

|

Emotional abuse | |||||||||

| 4 or more mths | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Less than 4 mths | 1.0 | 1.3 (0.7−2.5) | 2.7 (1.6−4.3) | 1.0 | 1.1 (0.5−2.0) | 1.8 (1.1−2.9) | 1.0 | 0.8 (0.4−1.7) | 1.1 (0.5−2.0) |

| Not at all |

1.0 |

1.5 (0.7−3.2) |

4.3 (2.6−7.0) |

1.0 |

1.0 (0.5−2.2) |

2.4 (1.4−4.0) |

1.0 |

0.8 (0.3−1.7) |

1.1 (0.5−2.5) |

|

Physical abuse | |||||||||

| 4 or more mths | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Less than 4 mths | 1.0 | 2.1 (1.2−3.8) | 2.7 (1.7−4.4) | 1.0 | 1.6 (0.9−2.9) | 2.0 (1.2−3.3) | 1.0 | 1.5 (0.8−2.8) | 1.7 (0.9−3.1) |

| Not at all | 1.0 | 2.3 (1.2−4.4) | 3.7 (2.2−6.2) | 1.0 | 1.4 (0.7−2.7) | 2.3 (1.3−3.9) | 1.0 | 1.1 (0.5−2.2) | 1.2 (0.6−2.4) |

Adjusted by maternal prenatal demographic factors (age, marital status, education, race, employment); prenatal behaviors/attitudes (cigarette consumption and binge drinking during pregnancy, anxiety and pregnancy ambivalence); infant factors (birth weight [continuous variable] and gender), and 6 month postpartum maternal behaviors and attitudes (mother-infant separation, employment, maternal stimulation/teaching of baby, maternal attitude of caregiving and postpartum depression).

Maltreatment subtypes adjusted by covariates listed above, as well as other types of maltreatment (neglect, emotional abuse and/or physical abuse).

Table 5.

Other independent predictors of substantiated maternally-perpetrated maltreatment (see Table 4; N=5890).

| Other maltreatment predictors | Unadjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* |

|---|---|---|

|

Any substantiated maternal maltreatment | ||

| Unmarried | 1.7 (1.5−1.9) | 1.4 (1.2−1.5) |

| Low education | 2.1 (1.7−2.6) | 1.6 (1.3−2.0) |

| Prenatal unemployment (either partner) | 3.1 (2.3−4.1) | 1.6 (1.2−2.3) |

| Cigarette use in pregnancy | 1.9 (1.6−2.2) | 1.3 (1.0−1.5) |

| Binge drinking in pregnancy | 3.6 (2.2−5.8) | 1.8 (1.1−3.1) |

| Anxiety symptoms in pregnancy | 2.5 (1.8−3.4) | 1.7 (1.2−2.4) |

| Mother-infant separation at 6 mths postpartum |

1.3 (1.1−1.6) |

1.2 (1.0−1.4) |

|

Substantiated maternal neglect | ||

| Young maternal age | 2.7 (2.0−3.8) | 1.7 (1.1−2.7) |

| Low education | 2.4 (1.9−3.2) | 2.0 (1.4−2.8) |

| Aboriginal race | 2.9 (1.8−4.5) | 2.6 (1.4−4.8) |

| Prenatal unemployment (either partner) | 3.3 (2.4−4.5) | 1.6 (1.0−2.5) |

| Binge drinking in pregnancy | 3.8 (2.2−6.6) | 2.4 (1.2−5.0) |

| Anxiety symptoms in pregnancy | 2.7 (1.9−3.9) | 2.0 (1.2−3.2) |

| Emotional abuse | 14.3 (11.5−17.9) | 7.7 (5.7−10.5) |

| Physical abuse | 10.2 (8.3−12.6) | 2.5 (1.8−3.5) |

Also adjusted for breastfeeding duration.

On examining the risk for specific subtypes of maltreatment, each was inversely associated with breastfeeding duration, in unadjusted and adjusted analyses (Table 4). However, only maternal neglect remained significant after adjusting for maltreatment subtypes, with a near 4-fold increase in odds for non-breastfed children compared with those breastfed 4 or more months (adjusted OR 3.8, 95% CI 2.1−7.0) (Model Chi-Square=745.9, df=24, P<0.001). The odds ratios for maternal neglect increased as the duration of breastfeeding decreased (Adjusted OR 1.0, 2.3 and 3.8 for breastfeeding “≥ 4 months”, “< 4 months” and “not at all”, respectively). Non-maternally-perpetrated neglect was not associated with breastfeeding duration. Other variables independently associated with maternal neglect included young maternal age, low education, Aboriginal race, binge drinking and anxiety in pregnancy, as well as other maltreatment subtypes (Table 5).

A number of confounding variables each contributed to a modest decrease in the odds ratio between unadjusted and adjusted analyses, including marital status, maternal education, young maternal age and unemployment, cigarette smoking and binge drinking (all measured during pregnancy), and maternal employment status 6 months postpartum. These same variables showed a confounding influence for maternal neglect, as did maternal race, infant birth weight, anxiety, depression and mother-infant separation at 6 months.

Sensitivity and attrition analyses

To see if proximity in time to breastfeeding modified these findings, the multinomial regression was repeated for children maltreated at a mean age ≤5 years. As expected, this revealed an even higher odds ratio for maltreatment in non-breastfed children ≤5 years old (unadjusted OR 8.1, 95% CI 3.9−16.7; >5 years old: OR 3.8, 95% CI 2.5−5.8; cf. Table 4). Maternal neglect revealed similar differences (children ≤5 years: unadjusted OR 7.8, 95% CI 3.7−16.2; >5 years: OR 5.7, 95% CI 3.2−10.1).

Similarly, the odds ratio for maternal maltreatment was even greater for multiple vs. single substantiated reports (>1 report: unadjusted OR 5.1, 95% CI 3.3−8.1; single report: OR 4.2, 95% CI 2.3−7.6).

Excluding siblings from the dataset also strengthened the association between breastfeeding duration and maternal maltreatment, specifically child neglect (N=5440, adjusted OR 4.6 [also adjusting for maltreatment subtypes], 95% CI 2.4−9.0).

At a 14-year study follow-up, 238 families (3.6% of study group) reported living outside the state of Queensland, which may have influenced reported maltreatment numbers from the state-based registry. Therefore, analyses were repeated for those families confirmed to be living within the state at this time (N=5723; 5088 in adjusted analysis). This revealed a modest decrease in odds ratios for most comparisons, but no loss of statistical significance. For example, the OR for maternal neglect in non-breastfed children was 3.3 (95% CI 1.7−6.4), after adjusting for confounders (including maltreatment subtypes).

Thus, these sensitivity analyses reveal that the association between breastfeeding duration and maternal maltreatment remains statistically significant, and is further strengthened, when examining younger children or those with multiple substantiated reports. Furthermore, the association remains statistically significant after excluding siblings or families who moved interstate during the study period.

Finally, our results would be biased if, in mothers excluded due to missing data, the observed associations between breastfeeding and maltreatment were non-existent or in the opposite direction. However, the attrition analysis26 found no difference between weighted and unweighted results, suggesting that attrition was unlikely to have substantively biased our findings.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to examine the relationship between breastfeeding duration and subsequent child maltreatment, using a large Australian birth cohort followed prospectively over 15 years. We clearly demonstrated that the lack of breastfeeding substantially increased the odds of maternal—but not non-maternal—maltreatment, and specifically child neglect. After adjusting for multiple confounders, there was a near 4-fold increase in odds of maternal neglect in non-breastfed children compared to those breastfed 4 or more months. These findings suggest that breastfeeding may play a protective role in helping to prevent maternal neglect.

With high incidence rates of maternally-perpetrated maltreatment reported in the U.S,1 this study is also the first to confirm these data in an Australian sample of children. In both countries, over 60% of substantiated maltreatment cases involved maternal perpetration.

Possible mechanisms

In lactating animals, suckling results in the peripheral and central production of the neuromodulatory hormone, oxytocin.27 Released into the peripheral circulation from the posterior pituitary gland, it is also produced by neurons of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, which project to numerous brain regions involved in maternal behavior. It has a broad range of central effects, characterized in both animal and human studies as the parasympathetic nervous system's “calm and connection” response, balancing the sympathetically-driven “fight or flight” response.27,28 In addition to its well-known effects on the initiation of labor and lactation, oxytocin helps to prepare the central nervous system for the long-term endeavor of child rearing. During pregnancy and the peripartum period, oxytocin receptors are induced in many brain regions involved in maternal behavior,29 and there is some evidence to suggest that suckling and infant-related stimulation may help to maintain these receptors.29,30 Oxytocin plays an essential role in the onset of maternal behavior in both rat and sheep models,31,32 and results in selective bonding between ewes and their newborn lambs.32 It appears to enhance two forms of memory and learning – spatial memory in the hippocampus33 and social memory in the amygdala34,35 – both of which may result in enduring differences in maternal care.33 In human randomized placebo-controlled trials, oxytocin (administered intranasally to facilitate central absorption) results in increased trust36 and accuracy in assessing facial affect,37 but decreased anxiety38 and reduced fear-related brain responses during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).39 In rat fMRI studies, both oxytocin and suckling activate similar brain regions involved in maternal behavior.40 Suckling also activates dopamine-associated reward processing regions (even more so than intraventricular cocaine in lactating rat dams),41 which may result in a long-term conditioned preference. This may help to explain the apparent long-lasting association between breastfeeding and maternal care.17 Similar results have been seen in the brain responses of human mothers to their own infant's facial expressions.42

Thus, based on a combination of animal and human studies, a plausible physiological mechanism exists through which breastfeeding may result in an altered pattern of mother-child bonding, and thus potentially reduce the risk of child neglect.

However, an alternative explanation for this association may be that a preexisting but unmeasured maternal characteristic is associated with both exposure and outcome variables. For example, women who decide to breastfeed may also be more sensitive to their child's physical or emotional needs, and thus less likely to be reported for child neglect. Britton et al22 recently showed that maternal sensitivity to infant cues predicted breastfeeding duration during the first year of life, but not vice versa. Furthermore, impaired maternal sensitivity has been associated with parental abuse and neglect,9 suggesting that it may at least partially confound the association between breastfeeding and maltreatment. Although maternal sensitivity was not directly measured in this study, the association between breastfeeding and neglect was adjusted for self-report measures of maternal “caring” and responsiveness, pregnancy ambivalence and postpartum depression, none of which remained significant in the final regression model.

With data from several animal studies suggesting that oxytocin receptor binding may be epigenetically programmed from early childhood,43-45 a mother's own childhood attachment experience may well influence both maternal sensitivity and the likelihood of breastfeeding success, and thus the risk for neglectful parenting.

Limitations

It should be noted that the interpretation of these results is also limited by the definitions of both exposure and outcome variables. Firstly, the breastfeeding variable did not distinguish “full” from “partial” breastfeeding (i.e. supplementing breastfeeds with infant formula or solid foods). However, as exclusive breastfeeding has been associated with higher maternal sensitivity than partial breastfeeding,22 this distinction may have further strengthened the observed associations. Additionally, if direct mother-infant contact is an important factor linking breastfeeding with a reduced risk of neglect, then breastfeeding also needs to be defined in terms of how frequently the infant is fed from the mother's breast, as opposed to receiving expressed breast milk by an alternate caregiver. Although this information was not directly available, only a small proportion of mothers were separated from their infants for more than 4 hours per week (13%, Table 2), suggesting that this did not substantially impact study findings. However, with over 50% of married mothers with infants under one year participating in the workforce today,46 future studies should certainly make this distinction.

The fact that all exposure and confounding variables were self-report measures is another source of potential bias. Although the outcome variables were obtained from independent maltreatment reports, the definitions of maltreatment were limited to those used by the government child protection agency. Other investigators have shown that important discrepancies exist between state-reported maltreatment data, self-report measures and observed maternal behavior.47 Although reports of suspected maltreatment were substantiated on formal investigation, socioeconomic, ethnic or other factors may still have biased the selection of cases. Neglect reports, for example, may have been skewed toward “physical neglect”, which is associated with socioeconomic disadvantage, compared to “emotional neglect”, which may occur more frequently in higher socioeconomic families but not come to the attention of child protection authorities.48 Finally, grouping unsubstantiated maltreatment with “no maltreatment” may also have biased the results, although most likely weakening true associations.

Although cohort studies are inherently limited in their ability to make causal inferences, a randomized controlled trial of breastfeeding and neglect would be neither feasible nor ethical, especially given our current state of knowledge regarding the positive benefits of breastfeeding.49,50 However, randomized controlled trials of breastfeeding promotion strategies, such as the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI),49 prenatal breastfeeding education, and postnatal support,51 have demonstrated substantial increases in breastfeeding duration and exclusivity during the first 6 to 12 months of life. Examining maltreatment reports or patterns of mother-infant interaction would be a logical extension to these studies, although any evidence of causality would still be indirect and could not distinguish between the effects of breastfeeding and the intervention itself. Additional cohort studies in different settings to our own, with more stringently defined variables and adjustment for maternal sensitivity may also be warranted in the future.

Implications

Each year in the United States, around 900,000 children (12 per 1000) become victims of child maltreatment, with almost 60% reported as a result of child neglect.1 Comparable rates of maltreatment (14 per 1000)52 have been reported in Queensland, Australia, from whence this study originated. Maternally-perpetrated maltreatment has also been noted in around 60% of substantiated cases, from both this study and from U.S. data1, with the child's biological mother—who is most often the primary caregiver—involved in almost 8 out of 10 substantiated neglect episodes.

Crittenden has argued that the most basic etiological factor underlying child neglect may be an impaired ability to form interpersonal relationships,48 which may help to explain observed associations between child neglect and teenage pregnancy, unemployment, substance abuse and anxiety symptoms. Breastfeeding, in addition to its other beneficial effects on maternal and child health,50 may be an important means of “training” a new mother in how to form a secure interpersonal relationship with her new baby, as has been the case with adoptive mothers who establish breastfeeding.53 Breastfeeding on demand, as recommended in the BFHI,49 may particularly help mothers establish a closer relationship with their baby, through responsive bidirectional touch, eye-to-eye gaze and the physiological response related to oxytocin and prolactin release.

Breastfeeding rates seen in this study (Table 3), consistent with another Australian study from this time period,54 were much higher than rates reported in the U.S. at that time.55 In 1988, only 53% of new mothers in the United States initiated breastfeeding, compared to 80% in Australia, and only 25% were breastfeeding their babies beyond 9 weeks postpartum. Although any link between breastfeeding and maltreatment might be attenuated in countries with lower breastfeeding rates, current breastfeeding initiation rates in the U.S. (74% of new mothers56) are more comparable to this Australian sample. However, only 42% of mothers in the U.S. are still breastfeeding by 6 months and only 11% are breastfeeding exclusively,56 as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics57. With breastfeeding rates lowest among those at highest risk for maltreatment (e.g. unmarried women with low education;56 see Table 5), this study provides additional evidence to support the active promotion of breastfeeding. Despite endorsement by the World Health Organization, UNICEF and the American Academy of Pediatrics, less than 2% of U.S. birthing hospitals are currently accredited as “baby friendly”, with rates 10 times higher in Australia.58

Conclusion

Although it is abundantly clear that breastfeeding duration is only one of many factors associated with maternal abuse and neglect, this study provides new evidence for a possible protective effect. While there is no single solution to the problem of child abuse and neglect, promoting breastfeeding may be a relatively simple and cost-effective additional means of strengthening the relationship between a mother and her child. This overarching goal would be best accomplished by also promoting parent education and long-term marital stability, and by providing economic and social support for new mothers who choose to stay at home with their babies. Together these factors may not only increase the duration of breastfeeding, but may ultimately help protect against maternally-perpetrated child abuse and neglect.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Queensland Government Department of Communities (L.S., M.J.O.), the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (J.M.N., M.O.J.), and the U.S. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23 HD43097) (L.S.). The authors would also like to thank Bill Bor, Jay Belsky and Peter Fonagy for reviewing the article and providing helpful insights and suggestions, and David Wood for helping to secure funding support. Claudia Kozinetz, and Gail Williams assisted with the statistical analysis, and Greg Shuttlewood and workers at the Child Protection Information System assisted in database management and linkage.

Abbreviations

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- fMRI

functional magnetic resonance imaging

- BFHI

Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative

- UNICEF

United Nations Children's Fund.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure/Conflict of Interest: None

This work does not represent a clinical trial.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Child Maltreatment 2005. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington D.C.: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Bellis MD, Baum AS, Birmaher B, et al. A.E. Bennett Research Award. Developmental traumatology. Part I: Biological stress systems. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:1259–1270. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strathearn L, Gray PH, O'Callaghan MJ, Wood DO. Childhood Neglect and Cognitive Development in Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants: A Prospective Study. Pediatrics. 2001 July;108(1):142–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collishaw S, Pickles A, Messer J, Rutter M, Shearer C, Maughan B. Resilience to adult psychopathology following childhood maltreatment: Evidence from a community sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31:211–229. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pianta R, Egeland B, Erickson MF. The antecedents of maltreatment: results of the Mother-Child Interaction Research Project. In: Cicchetti D, Carlson V, editors. Child maltreatment: theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1989. pp. 203–253. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pears KC, Capaldi DM. Intergenerational transmission of abuse: a two-generational prospective study of an at-risk sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25:1439–1461. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sidebotham P, Heron J. Child maltreatment in the “children of the nineties”: A cohort study of risk factors. Child Abuse Negl. 2006;30:497–522. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belsky J. Etiology of child maltreatment: a developmental-ecological analysis. Psychol Bull. 1993;114:413–434. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crittenden PM, Bonvillian JD. The relationship between maternal risk status and maternal sensitivity. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1984;54:250–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1984.tb01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stern JM. Offspring-induced nurturance: animal-human parallels. Dev Psychobiol. 1997;31:19–37. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(199707)31:1<19::aid-dev3>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiodera P, Salvarani C, Bacchi-Modena A, et al. Relationship between plasma profiles of oxytocin and adrenocorticotropic hormone during suckling or breast stimulation in women. Horm Res. 1991;35:119–123. doi: 10.1159/000181886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinrichs M, Meinlschmidt G, Neumann I, et al. Effects of Suckling on Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Responses to Psychosocial Stress in Postpartum Lactating Women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4798–4804. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uvnas-Moberg K, Eriksson M. Breastfeeding: physiological, endocrine and behavioural adaptations caused by oxytocin and local neurogenic activity in the nipple and mammary gland. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:525–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine A, Zagoory-Sharon O, Feldman R, Weller A. Oxytocin during pregnancy and early postpartum: Individual patterns and maternal-fetal attachment. Peptides. 2007;28:1162–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mezzacappa ES, Katlin ES. Breast-feeding is associated with reduced perceived stress and negative mood in mothers. Health Psychol. 2002;21:187–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauer WD, Twentyman CT. Abusing, neglectful, and comparison mothers’ responses to child-related and non-child-related stressors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:335–343. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ. Breast feeding and later psychosocial adjustment. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1999;13:144–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1999.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lvoff NM, Lvoff V, Klaus MH. Effect of the Baby-Friendly Initiative on Infant Abandonment in a Russian Hospital. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:474–477. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.5.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buranasin B. The effects of rooming-in on the success of breastfeeding and the decline in abandonment of children. Asia Pac J Public Health. 1991;5:217–220. doi: 10.1177/101053959100500305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keeping JD, Najman JM, Morrison J, Western JS, Andersen MJ, Williams GM. A prospective longitudinal study of social, psychological and obstetric factors in pregnancy: response rates and demographic characteristics of the 8556 respondents. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96:289–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1989.tb02388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott JA, Binns CW. Factors associated with the initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a review of the literature. Breastfeed Rev. 1999;7:5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Britton JR, Britton HL, Gronwaldt V. Breastfeeding, Sensitivity, and Attachment. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1436–e1443. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bedford A, Foulds G. Delusions-Symptoms-States Inventory - State of Anxiety and Depression. NFER Publishing; Berkshire: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kruse RL, Ewigman BG, Tremblay GC. The Zipper: a method for using personal identifiers to link data while preserving confidentiality. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25:1241–1248. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.SCRCSSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Commonwealth/State Service Provision). Report on Government Services 2000. AusInfo. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hogan JW, Roy J, Korkontzelou C. Handling drop-out in longitudinal studies. Stat Med. 2004;23:1455–1497. doi: 10.1002/sim.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neumann I, Ludwig M, Engelmann M, Pittman QJ, Landgraf R. Simultaneous microdialysis in blood and brain: oxytocin and vasopressin release in response to central and peripheral osmotic stimulation and suckling in the rat. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;58:637–645. doi: 10.1159/000126604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uvnas-Moberg K. The Oxytocin Factor. Da Capo Press; Cambridge, MA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meddle SL, Bishop VR, Gkoumassi E, van Leeuwen FW, Douglas AJ. Dynamic Changes in Oxytocin Receptor Expression and Activation at Parturition in the Rat Brain. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5095–5104. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedersen CA, Caldwell JD, Peterson G, Walker CH, Mason GA. Oxytocin activation of maternal behavior in the rat. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;652:58–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb34346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedersen CA, Ascher JA, Monroe YL, Prange AJ., Jr Oxytocin induces maternal behavior in virgin female rats. Science. 1982;216:648–650. doi: 10.1126/science.7071605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keverne EB, Kendrick KM. Oxytocin facilitation of maternal behavior in sheep. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;652:83–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb34348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomizawa K, Iga N, Lu YF, et al. Oxytocin improves long-lasting spatial memory during motherhood through MAP kinase cascade. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:384–390. doi: 10.1038/nn1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferguson JN, Young LJ, Hearn EF, Matzuk MM, Insel TR, Winslow JT. Social amnesia in mice lacking the oxytocin gene. Nat Genet. 2000;25:284–288. doi: 10.1038/77040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Engelmann M, Ebner K, Wotjak CT, Landgraf R. Endogenous oxytocin is involved in short-term olfactory memory in female rats. Behav Brain Res. 1998;90:89–94. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature. 2005;435:673–676. doi: 10.1038/nature03701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Domes G, Heinrichs M, Michel A, Berger C, Herpertz SC. Oxytocin improves “mind-reading” in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:731–733. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heinrichs M, Baumgartner T, Kirschbaum C, Ehlert U. Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:1389–1398. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00465-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirsch P, Esslinger C, Chen Q, et al. Oxytocin Modulates Neural Circuitry for Social Cognition and Fear in Humans. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11489–11493. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3984-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Febo M, Numan M, Ferris CF. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Shows Oxytocin Activates Brain Regions Associated with Mother-Pup Bonding during Suckling. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11637–11644. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3604-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferris CF, Kulkarni P, Sullivan JM, Jr., Harder JA, Messenger TL, Febo M. Pup Suckling Is More Rewarding Than Cocaine: Evidence from Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Three-Dimensional Computational Analysis. J Neurosci. 2005;25:149–156. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3156-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strathearn L, Li J, Fonagy P, Montague PR. What's in a smile? Maternal brain responses to infant facial cues. Pediatrics. 2008 doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1566. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Champagne FA, Weaver ICG, Diorio J, Sharma S, Meaney MJ. Natural Variations in Maternal Care are Associated with Estrogen Receptor Alpha Expression and Estrogen Sensitivity in the Medial Preoptic Area. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4720–4724. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Champagne FA, Weaver ICG, Diorio J, Dymov S, Szyf M, Meaney MJ. Maternal Care Associated with Methylation of the Estrogen Receptor-α1b Promoter and Estrogen Receptor-α Expression in the Medial Preoptic Area of Female Offspring. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2909–2915. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pedersen CA, Boccia ML. Oxytocin links mothering received, mothering bestowed and adult stress responses. Stress. 2002;5:259–267. doi: 10.1080/1025389021000037586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohany SR, Sok E. Trends in labor force participation of married mothers of infants. Monthly Labor Review. 2007;130:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGee R, Wolfe D, Yuen S, WIlson S, Carnochan J. The measurement of maltreatment: A comparison of approaches. Child Abuse Negl. 1995;19:233–249. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)00119-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crittenden PM. Child Neglect: Causes and Contributors. In: Dubowitz H, editor. Neglected children: Research, practice, and policy. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kramer MS, Chalmers B, Hodnett ED, Sevkovskaya Z, Dzikovich I, Shapiro S, et al. Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT): A Randomized Trial in the Republic of Belarus. JAMA. 2001;285:413–420. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, et al. Breastfeeding and Maternal and Infant Health Outcomes in Developed Countries. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2007. Report No.: 153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Su LL, Chong YS, Chan YH, et al. Antenatal education and postnatal support strategies for improving rates of exclusive breast feeding: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335:596. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39279.656343.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) Child Protection Australia 2004−05. AIHW; Canberra: 2006. Report No.: CWS 26. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gribble KD. Mental health, attachment and breastfeeding: implications for adopted children and their mothers. Int Breastfeed J. 2006;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.NHMRA . Dietary Guidelines for Children and Adolescents in Australia incorporating the Infant Feeding Guidelines for Health Workers. AusInfo; Canberra, ACT, Australia: Apr 10, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Visness CM, Kennedy KI. Maternal employment and breast-feeding: findings from the 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:945–950. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Breastfeeding trends and updated national health objectives for exclusive breastfeeding--United States, birth years 2000−2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:760–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Work Group on Breastfeeding Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk. Pediatrics. 1997;100:1035–1039. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.6.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.World Health Organization, UNICEF [2007 Oct 10];WHO/UNICEF Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative 2007. Available from: URL: www.babyfriendly.org.