Abstract

We report on three experiments that provide a real-time processing perspective on the poor comprehension of Broca’s aphasic patients for non-canonically structured sentences. In the first experiment we presented sentences (via a Cross Modal Lexical Priming (CMLP) paradigm) to Broca’s patients at a normal rate of speech. Unlike the pattern found with unimpaired control participants, we observed a general slowing of lexical activation and a concomitant delay in the formation of syntactic dependencies involving “moved” constituents and empty elements. Our second experiment presented these same sentences at a slower rate of speech. In this circumstance, Broca’s patients formed syntactic dependencies as soon as they were structurally licensed (again, a different pattern from that demonstrated by the unimpaired control group). The third experiment used a sentence-picture matching paradigm to chart Broca’s comprehension for non-canonically structured sentences (presented at both normal and slow rates). Here we observed significantly better scores in the slow rate condition. We discuss these findings in terms of the functional commitment of the left anterior cortical region implicated in Broca’s aphasia and conclude that this region is crucially involved in the formation of syntactically-governed dependency relations, not because it supports knowledge of syntactic dependencies, but rather because it supports the real-time implementation of these specific representations by sustaining, at the least, a lexical activation rise-time parameter.

Keywords: Aphasia, Broca’s area, Syntax, Slow rise time, Gap filling, Rate of speech, On-line, Priming, Sentence processing, Neurolinguistics

1. Introduction

This paper provides data from Broca’s aphasia concerning a timing parameter of syntactic processing and its neurological underpinning. We have focused on this syndrome for two reasons: (1) there are specific linguistic processing deficits associated with it; and (2) it has lesion-localizing value—the deficits implicate damage to left inferior frontal cortex.

As is well known, Broca’s aphasia is variably associated with large superficial and deep lesions, often including, but certainly not confined to, the classically delimited Broca’s area—viz., BA (Brodmann Area) 44 and BA 45 (Alexander, Naeser, & Palumbo, 1990; Benson, 1985; Mohr, 1976; Vignolo, 1988). Still, this larger, indeterminate anterior region is clearly distinguishable from the posterior region associated with Wernicke’s aphasia (Benson, 1985; Tonkonogy, 1986; Vignolo, 1988). So, specific linguistic deficits found only in Broca’s aphasia are reasonably certain to be based on a different neuroanatomical substrate from those found only in Wernicke’s aphasia. And such differences have, indeed, been reported, including differences involving real-time processing parameters of the sort to be described in the present paper. In any case, we will not be concerned here with the cortical area implicated in Wernicke’s aphasia, but only with the commitment to syntactic processing of the region associated with Broca’s aphasia—i.e., with a left anterior cortical region, however imprecisely bounded it is.2

Not all syntactic operations—nor perhaps even very many—seem to rely on the integrity of left inferior frontal cortex. In fact, several past analyses of comprehension in Broca’s aphasia suggest that only a minimal functional deficit following lesions to this area arises: the inability to establish syntactic dependencies (e.g., Grodzinsky, 1986, 2000, 2006; Mauner, Fromkin, & Cornell, 1993; Hickok, Zurif, & Conseco-Gonzalez, 1993; Friedmann & Shapiro, 2003; Thompson, Shapiro, Tait, Jacobs, & Schneider, 1996). This deficit prevents the hypothesized formation of links between positions at which noun phrases (NPs) appear (are heard) in sentences and positions at which they are interpreted.

Dependencies of this sort must be accounted for by any syntactic theory. Relevant frameworks are provided in, among other places, Pollard and Sag (1994) (Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar) and Chomsky (1981) (theory of Government and Binding), an important tenet of which is constituent movement. In this latter theory, movement of a phrasal constituent leaves a trace—an abstract, phonologically unrealized placeholder—in the vacated position. On this view, traces are crucial for the assignment of thematic roles in a sentence, such roles being assigned to canonical positions regardless of the identity of the assignee and of the actual ordering of constituents in the sentence. So if a thematic position contains a trace, then the trace is assigned the thematic role and the moved constituent, or antecedent, that left the trace gets its role only indirectly, by being linked to the trace. Consider as an example the following notated non-canonical sentence, “(The boy)i that the horse chased (t)i is tall.” The transitive verb “chase” assigns two roles: the role of agent to the subject on its left (“horse”) and the role of entity-acted-upon to the trace position marked by “t” on its right. In effect, to ensure proper comprehension, the NP “the boy,” though heard at the beginning of the sentence, is hypothesized to be interpreted—i.e., assigned its role of entity-acted-upon—at its canonical position directly after the verb, as indexed by the trace or “t.” The dependency relation between the two positions is shown by the subscript “i.”

The application of this theory to aphasia, first proposed by Grodzinsky (1986), encompasses more than just the idea that Broca’s patients are unable to represent syntactic dependencies involving traces. There is another part to it as well, which is that, faced with a thematically unassigned constituent, Broca’s patients resort to their knowledge of probabilities acquired through experience: namely, they apply a linearly ordered (non-grammatical) “agent-first” strategy (Bever, 1970), incorrectly interpreting the first noun phrase (NP) encountered as the agent of the action. But since this strategy is hypothesized to apply in the context of an otherwise normally elaborated syntactic representation, the structures the patients form end up with two agents, leading them to guess at the interpretation. Of course, also consistent with this argument is the fact that Broca’s show relatively spared comprehension for all sorts of canonical structures, that is, for structures in which the first NP preceding the verb is correctly (grammatically) mapped as agent. In this way, (e.g., Grodzinsky, 1986, 2000, 2006) and, with variations, a number of other investigators (e.g., Hickok et al., 1993; Mauner et al., 1993) account for a fairly large body of comprehension data at the sentence level. For lists of studies attesting to this robust result pattern and, equally, for references to, and critiques of, the several analyses vaunting variability, see, e.g., Drai, Grodzinsky, and Zurif (2001); Drai and Grodzinsky (2006a, 2006b); Grodzinsky, Piñango, Zurif, and Drai (1999).

This syntactic limitation in Broca’s aphasia is especially marked when the formation of an antecedent-trace link is studied online, that is, as comprehension temporally unfolds. The relevant fact here is that traces-the “gaps” they index—normally appear to have real-time processing consequences (Swinney & Fodor, 1989 and articles therein). This has been most commonly shown by studies of lexical priming wherein one observes that the meaning of a displaced constituent or antecedent is activated when it is first encountered in a sentence, and then, in an operation referred to as gap filling, reactivated at the site indexed by the trace (Hickok, Conseco-Gonzalez, Zurif, & Grimshaw, 1992; Love, 2007; Love & Swinney, 1996; Nicol, Fodor, & Swinney, 1994; Nicol & Swinney, 1989; Swinney & Fodor, 1989; Swinney & Osterhout, 1990; Tanenhaus, Boland, Garnsey, & Carlson, 1989; Zurif, Swinney, Prather, Wingfield, & Brownell, 1995).3 Consider our earlier example, “(The boy)i that the horse chased (t)i is tall.” Using priming to measure activation of a lexical item, one observes “boy” to be activated just after being heard and again at the gap indexed by the “t” where there is no phonologically realized word at all. Moreover, the word “boy” does not show activation just before the verb “chased.” This last point is crucial; it signifies that activation for “boy” at the gap is not due to residual activation from its earlier appearance, but is rather the result of its reactivation. In effect, for neurologically intact subjects the link between a displaced constituent and its trace is reflexively formed in real-time, at the moment the trace site or gap is encountered. By contrast, Broca’s patients do not show reactivation of the antecedent at the trace site—they do not form syntactic dependency relations in real-time, or at least, not within the normal time frame (Swinney, Zurif, Prather, & Love, 1996; Zurif, Swinney, Prather, Solomon, & Bushel, 1993).

A number of clinical observations suggest that this failure to form syntactic dependencies (to fill gaps) is the consequence of a processing limitation, not the reflection of an unalterable loss of syntactic knowledge. For one thing, Broca’s patients occasionally show dissociations between comprehension capacity and the capacity to make grammatical judgments (e.g., Linebarger, Schwartz, & Saffran, 1983). That is, these patients do not always show an overarching syntactic limitation that equally diminishes all language activities, as would be expected if a part of syntactic knowledge were absent. A second relevant clinical finding is that the Broca’s comprehension problem has sometimes been relieved by relaxing various task demands—by repeating sentences and delivering them more slowly (e.g., Gardner, Albert, & Weintraub, 1975; Lasky, Weidner, & Johnson, 1976; Pashek & Brookshire, 1982; Poeck & Pietron, 1981; but see Blumstein, Katz, Goodglass, Shrier, & Dworetzky, 1985 for contrary evidence). So the knowledge of syntactic dependencies seems to be there; the problem seems to be accessing it in real-time. And this, in turn, seems related to the particular processing resources demanded by the gap-filling operation.

One processing demand has to do with the fact that the operation is fast acting (Fodor, 1983). As we have already noted, the data show that the moved constituent is normally reactivated as soon as it is structurally licensed to do so—at the moment the gap, or trace, site is encountered (e.g., Nicol & Swinney, 1989). It is this temporal parameter of gap-filling that forms the topic of the present report. To be more specific, we provide evidence consistent with the idea that left inferior frontal cortex enters into syntactic processing, not because it supports syntactic knowledge, but rather because, whatever else; it sustains the requisite lexical activation speed needed for the real-time formation of a syntactic dependency.

We have argued this last point in some earlier articles and book chapters (e.g., Swinney et al., 1996; Zurif, 1995, 2000). We have even provided some preliminary evidence that Broca’s patients do eventually reactivate the antecedent, but that they do so beyond the gap-too late to support normal syntactic processing (Love, Swinney, & Zurif, 2001; Swinney & Love, 1998; also see Burkhardt, Piñango, & Wong (2003) for evidence of late reactivation). But the two-fold argument that there is a connection between speed of lexical activation and successful syntactic processing, and that normal lexical access speed is dependent upon the integrity of the cortical area implicated in Broca’s aphasia, has only been indirectly established; the data on slow lexical activation (or slow rise time as it’s also termed) in the face of left inferior frontal damage have been gathered quite apart from considerations of syntactic processing. They come from one study of polysemy (Swinney, Zurif, & Nicol, 1989) and from single case studies using a list priming paradigm (Prather, Zurif, Stern, & Rosen, 1992; Prather, Zurif, Love, & Brownell, 1997). In this latter paradigm a subject is required to make a lexical decision for each word in an ongoing list, some of the adjacent words in this list being semantically associated, most not. An important feature is that the words rapidly follow one another in such a way as to minimize relatedness expectations and post-lexical checking—two strategies that establish controlled, as opposed to automatic, processing (e.g., Shelton & Martin, 1992). Therefore the list priming paradigm can be said to foster automatic processing. In this experimental situation the Broca’s patients that were studied did not show priming until the words were separated from each other by 1500 ms—they activated word meanings slower than normally (Prather et al., 1992, 1997). Thus, until the present, our claim of a connection between a temporal alteration in lexical processing and the syntactic problem in Broca’s comprehension has been circumstantial: viz., Broca’s patients who do not show ‘normal’ lexical activation speed do not demonstrate gap filling in real time.

The three studies that we present here, however, take us beyond this circumstance. The first of these studies focuses on how Broca’s patients both activate and reactivate lexical information under normal speech conditions—that is, when words in a sentence are presented at a normal speaking rate. We already know that Broca’s patients show slow lexical activation when faced with list formats. Here we seek to establish whether or not they also show this temporal alteration in a sentence context. Also, we seek to confirm earlier indications that although the patients fail to reactivate lexical items at their gap sites, they do reactivate them eventually, but too late to allow normal syntactic processing (Love et al., 2001; Swinney & Love, 1998; Burkhardt et al., 2003). In effect, in our first experiment we seek evidence that the syntactic comprehension problem in Broca’s aphasia is best understood, not as a loss of knowledge of representations containing syntactic dependencies, but as a change in the processing resources that sustain the normal speed of lexical activation, thereby disrupting the reflexive syntactic operation of gap-filling.

Our second study, undertaken with the same aim in mind, provides, perhaps, an even more important test of our hypothesis that slow lexical activation underlies the syntactic problem in Broca’s aphasia. In this study, we examine whether Broca’s patients can establish syntactically-governed dependency relations—whether they can reactivate moved constituents at gap sites—when sentences are spoken more slowly than is usual, but in a manner that still sounds normal. To this end, we digitally modified the input rate, slowing it to 3.4 syllables per second. This is just outside the range of the normal speech rate which is 4 to 6 syllables per second. Decreasing the input rate allowed even the gap site to have an expanded temporal window by which to afford the formation of a syntactic dependency in the face of slow lexical activation. (Love et al., 2001; Swinney & Love, 1998; Swinney, Love, Oliver, Bouck, & Zurif, 1999)

Both of these two studies make use of an on-line task called cross-modal lexical priming (CMLP) (Swinney, Onifer, Prather, & Hirshkowitz, 1979). In this task, for any one trial, participants listen to a sentence over earphones, and at one point while listening to the sentence, are required to make a lexical decision for a visually presented letter string target flashed on a screen in front of them. Words formed by the letter strings are either related or unrelated to the moved constituent in the sentence. By locating the letter strings at various points during the auditory presentation of the sentence, we can monitor when the antecedent—the moved constituent—is serving as a priming word for the related visual target. That is, we can monitor when the meaning of the antecedent in the sentence has been activated, or reactivated.

Our third study shifts the focus from on-line behavior to off-line comprehension. Specifically, we use a sentence-picture matching task to assess the Broca’s patients’ understanding of who’s doing what to whom—who the agent is, who the entity-acted-upon is—when this information is conveyed by non-canonically structured sentences. And crucially, we test understanding for these sentences both when they are spoken at a normal speed and at the slow rate of 3.8 syllables per second. Our aim here is to determine if greater success in real-time gap-filling for sentences presented at this slower rate is accompanied by greater success in off-line comprehension.

Our specific hypotheses are as follows: With normally rapid speech, the patients will show both delayed lexical activation when encountering the moved constituent near the beginning of the utterance and delayed reactivation of that constituent at the gap site—the latter delay disrupting the normal formation of a syntactic dependency. But faced with a slower rate of speech input, the patients will show both normal gap filling and an improvement in their comprehension of non-canonically structured sentences.

2. Experiment 1: Normal rate of speech input

In this experiment we use an on-line cross-modal lexical priming (CMLP) task (Swinney et al., 1979), with auditory sentences presented at a normal rate of speech to examine whether Broca’s aphasic patients show slower-than-normal lexical activation of words when the words are presented as part of an ongoing auditory sentence. Additionally, we seek to confirm earlier indications that Broca’s patients exhibit a similar slow rise time of activation of an antecedent at a gap position. Such a finding would bolster the claim that the syntactic comprehension problem in Broca’s aphasia is best understood as a disruption in automatic syntactic operations underlying gap-filling due to a change in the processing resources that sustain the normal speed of lexical activation (Prather et al., 1997). Moreover, such findings would pose challenges for claims that Broca’s aphasia represents a loss of the (specific) syntactic knowledge concerning the dependency relations necessary for gap-filling (Grodzinsky, 1990).

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Participants

We tested two groups of participants (Tables 1a, 1b): a group of 8 Broca’s aphasic patients (age at time of testing: 47-80; mean: 62.4 years) and 4 neurologically unimpaired controls (that were age- and education-matched to four of the Broca’s patients; age at time of testing: 47-74; mean: 62 years). Participants were tested at one of two sites: The Laboratory for Research on Aphasia and Stroke at The University of California, San Diego (San Diego; n = 4) and at The Aphasia Research Center at the Boston Veterans’ Administration Medical Center (Boston; n = 4). All of the control participants were tested at The Aphasia Research Center at the Boston Veterans’ Administration Medical Center. All participants were paid $15 per visit.

Table 1a.

Demographic and lesion information for all patients in experiments 1, 2, and 3a

| Patient | Testing location | Aphasia severity levelc | Gender | Age at testing | Years post onset | Hemiparesis? | Education | Lesiond |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment one (n = 8) | ||||||||

| BT | San Diego | 1 | M | 50 | 11 | R/wheelchair | M.D. | L frontal lobe extending into parietal and temporal pole regions—sparing the STS |

| CE | San Diego | 3.5 | F | 52 | 14 | R weakness | 2 years college | L basal ganglia, internal capsule, lenticular nucleus |

| CL | San Diego | 2 | M | 59 | 8 | R weakness | MA | L basal ganglia, deep white matter, frontoparietal cortex |

| FTb | San Diego | 4 | M | 61 | 5 | NO | 8th grade | L IFG extending into the basal ganglia, internal capsule, lenticular nucleus |

| CF | Boston | 1 | M | 68 | 32 | R weakness | HS | Large L dorsolateral frontal lobe lesion involving almost all of the inferior and middle frontal gyri. The lesion included all of Broca’s area and the white matter deep to Broca’s area, with no involvement of the temporal and parietal lobes |

| CJ | Boston | 1 | F | 58 | 10 | R/wheelchair | HS | Large left fronto-parietal lesion |

| BJ | Boston | 2 | F | 54 | 11 | Nursing | R weakness | Large L fronto-parietal lesion involving all of IFG including Broca’s area and the white matter underlying it |

| DR | Boston | 1.5 | M | 82 | 21 | R weakness | 2 years college | L frontal lesion involving Broca’s area with deep extension across to L frontal horn and into anterior temporal pole sparing Wernicke’s area |

| Experiment two (n = 9) | ||||||||

| BT | San Diego | 1 | M | 50 | 11 | R/wheelchair | M.D. | L frontal lobe extending into parietal and temporal pole regions—sparing the STS |

| CE | San Diego | 3.5 | F | 52 | 14 | R weakness | 2 years college | L basal ganglia, internal capsule, lenticular nucleus |

| CL | San Diego | 2 | M | 59 | 8 | R weakness | MA | L basal ganglia, deep white matter, frontoparietal cortex |

| FTb | San Diego | 4 | M | 61 | 5 | NO | 8th grade | L IFG extending into the basal ganglia, internal capsule, lenticular nucleus |

| HB | San Diego | 1 | M | 68 | 12 | R weakness | MBA | Left frontoparietal infarct |

| PY | San Diego | 3.5 | M | 53 | 5 | NO | HS | Large area of ischemia involving the L frontal cortical region & deeper structures in the basal ganglia |

| RY | San Diego | 3 | M | 52 | 3 | R weakness | BA | Extensive area of low density involving the left parietal lobe extending anteriorly |

| ST | San Diego | 1 | F | 47 | 2 | R weakness | HS | L MCA embolic stroke; distribution encompasses broad left frontal lobe region |

| TA | San Diego | 1 | F | 40 | 5 | R weakness | HS | L frontotemporal lobe infarct with sparing of the superior temporal region |

| Experiment three (n = 8) | ||||||||

| CE | San Diego | 3.5 | F | 52 | 14 | R weakness | 2 years college | L basal ganglia, internal capsule, lenticular nucleus |

| FTb | San Diego | 4 | M | 61 | 5 | NO | 8th grade | L IFG extending into the basal ganglia, internal capsule, lenticular nucleus |

| HB | San Diego | 1 | M | 68 | 12 | R weakness | MBA | Left frontoparietal infarct |

| NS | San Diego | 2 | F | 78 | 1 | R hemiparesis | HS | L MCA infarct affecting frontal, anterior temporal and inferior parietal lobes |

| OMb | San Diego | 3 | M | 80 | 4 | NO | HS | Left superior perisylvian lesion extending anteriorly with sparing of posterior superior temporal regions |

| PY | San Diego | 3.5 | M | 53 | 5 | NO | HS | Large area of ischemia involving the L frontal cortical region & deeper structures in the basal ganglia |

| SH | San Diego | 3 | M | 60 | 3 | R weakness | Ph.D. | L frontal lesion extending posteriorly to inferior parietal lobule |

| ST | San Diego | 1 | F | 47 | 2 | R weakness | HS | L MCA embolic stroke; distribution encompasses broad left frontal lobe region |

Some patients participated in multiple experiments.

We note that the profiles of two of our patients (FT, OM) do not line up perfectly with the standard BDAE profile for Broca’s aphasia. However both demonstrate dysfluent speech and have anterior lesions sites, involving Broca’s area. They are therefore included in the patient groups.

Aphasia severity level scores are taken from the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination.

L = left; IFG = inferior frontal gyrus; MCA = Middle Cerebral Artery; STS = Superior Temporal Sulcus.

Table 1b.

Demographic Information for all unimpaired control participants in experiments 1, 2, and 3a

| Control | Testing |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Gender | Age | Education | |

| Experiment one | ||||

| BJ | Boston | F | 57 | 14 years |

| CR | Boston | F | 47 | H.S. |

| QC | Boston | F | 71 | B.A. |

| SM | Boston | F | 74 | H.S. |

| Experiment two | ||||

| BR | Boston | M | 75 | H.S. |

| CF | Boston | F | 73 | HS |

| CP | Boston | F | 71 | H.S. |

| JR | Boston | F | 75 | H.S. |

| SF | Boston | F | 66 | 14 years |

| SP | Boston | M | 73 | HS |

| Experiment three | ||||

| AH | San Diego | F | 73 | H.S. |

| BD | San Diego | M | 74 | H.S. |

| TA | San Diego | F | 68 | H.S. |

| PM | San Diego | F | 47 | H.S. |

| FN | San Diego | M | 76 | M.A. |

| JT | San Diego | F | 70 | H.S. |

| QT | San Diego | F | 71 | B.A. |

| JT | San Diego | F | 66 | M.A. |

| ST | San Diego | M | 48 | B.S. |

| WN | San Diego | F | 69 | B.A. |

Some control participants participated in more than one experiment.

Broca’s aphasic patients

All patients were native English speakers with normal or corrected-to-normal auditory and visual acuity for age, and were right handed prior to their stroke. All patients had left hemisphere damage with a single, relatively localized lesion site, predominantly in anterior regions/structures. The diagnosis of Broca’s Aphasia was based on the convergence of clinical consensus and the results of a standardized aphasia examination—the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE-version 2, Goodglass & Kaplan, 1972). At the time of testing, all participants had retained the defining features of their original diagnosis. We note that the profile of one of our patients (FT) does not line up perfectly with the standard BDAE profile for Broca’s aphasia. However he demonstrates agrammatic speech and his lesion site is anterior, involving Broca’s area. He is therefore included in the patient group. No patient had a previous history of other infarcts, and all were neurologically and physically stable (i.e., at least 6 months post onset), with no history of active or significant alcohol and/or drug abuse, no history of active psychiatric illness, and no history of other significant brain disorder or dysfunction (e.g., Alzheimer’s/dementia, senility, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, Korsakoff’s, mental retardation).

Neurologically unimpaired controls

All participants were right-handed native English speakers, with normal or corrected-to-normal visual and auditory acuity for age. No participants had a history of: (a) active or significant alcohol and/or drug abuse; (b) active psychiatric illness; (c) other significant brain disorder or dysfunction.

2.1.2. Materials

The test items consisted of 40 experimental object relative sentences like the following:

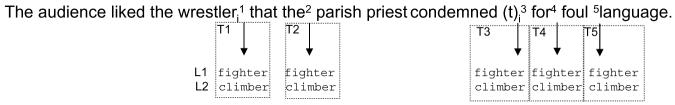

The audience liked the wrestleri1 that the2 parish priest condemned (t)i3 for4 foul5 language.

In these sentences, the relativized noun (wrestler) is co-indexed with the trace (t) in the direct object position of the relative clause (hereafter referred to as the ‘gap’). This noun (wrestler) therefore serves as the antecedent of the trace, and hence is interpreted as the direct object of the relative clause verb (condemned).

In order to measure priming effects in this CMLP task, participants make binary lexical decisions to visually presented letter strings (visual probes). Two visual probe words were chosen for each sentence. One of the visual probe words (the “related” probe; e.g., fighter for the example above) was a close semantic associate of the antecedent. Semantic association was determined by both published word association data (Jenkins, 1970) and data previously collected from college-age and elderly adults (Love & Swinney, 1996). The other visual probe word (the “control” probe; e.g., climber for the example above) was not semantically associated with the antecedent or with any other word in the sentence (to avoid accidental priming). Priming is measured by comparing response times to the related and control probes—faster response times to the related probes indicate a priming effect. Importantly, priming effects in CMLP tasks reflect activation, not integration, of the visual probe into the ongoing auditory sentence (Nicol, Swinney, Love, & Hald, 2006).

The visual probes were paired with sentences using a switched target design such that a related probe for one sentence appeared as a control probe for a different sentence. Thus over all sentences, the set of related probes is identical to the set of control probes, minimizing the possibility that any observed priming effects are due to lexical differences (e.g., frequency, length differences) between the related and control probes.

In order to establish the time course of activation of the antecedent, the related and control visual probes were presented at five positions in the ongoing auditory sentence (indicated approximately by superscript numerals in the example above). Probe position 1 is immediately at the offset of the antecedent. Probe position 2 is 300 ms “downstream” from probe position 1. This position allowed us to widen the window of measurement and observe whether the Broca’s patients had activated the antecedent, but with a slower-than-normal rise time. Probe position 3 is at the gap position, where priming of the antecedent is expected for unimpaired subjects. Probe position 4 is 300 ms after the gap and Probe position 5 is 500 ms after the gap. Like probe position 2, probe positions 4 and 5 also widened the measurement window, allowing us to determine if Broca’s patients also exhibit a slower-than-normal rise time for reactivation of the antecedent at the gap.

In addition to these experimental sentences, we created 50 filler sentences that were similar in length and structure to the experimental sentences, but with some variation in the positioning of the relative clause. Forty of these filler sentences were paired with a non-word probe (that obeyed English phonotactic constraints; e.g., flep), and 5 were paired with a real-word letter string, balancing the number of ‘word’ and ‘non-word’ responses over the full set of items. In addition, the position of the visual probe varied for the filler sentences; for some it occurred early on in the sentence, for some roughly in the middle, and for others near the end of the sentence, to prevent the (unlikely) occurrence of subjects anticipating the probe positions.

The 90 sentences (40 experimental; 50 filler) were pseudo-randomly ordered into a single script, such that no more than three sentences of a given condition (experimental or filler; word or non-word) occurred in a row. The sentences were recorded by a male native English speaker at a normal rate of speech (4.47 syllables per second), and were digitized at 22 K samples per second. The recorded sentences were saved on one channel of a stereo sound file. Digital tones, in the form of a 100 ms 1 KHz pulse, were recorded (via digital techniques) for all sentences on the second inaudible stereo channel, at times appropriate for presentation of the visual probes.

For playback, the single channel containing the auditory form of the sentence was split into two channels, and played to the subjects in stereo over a set of headphones. The single channel containing the digital tone was transmitted to the RTLAB V11 software program, and served to trigger the occurrence of the visual probe in the center of a display monitor. This second channel containing the digital tones was therefore completely inaudible to the subjects, and could not have served as a cue for the appearance of the visual probe. Simultaneously with the appearance of the visual probe, the software package initiated a timing function to record the button press response times indicating a subject’s binary word/non-word lexical decision (with millisecond accuracy).

2.1.3. Design

This CMLP study used a within subjects design, so that every participant saw every sentence in every condition. The visual probes and probe positions were counterbalanced across multiple tapes (to counterbalance the probe positions) and multiple lists (to counterbalance the related and control probes). Each tape contained the same experimental and filler sentences in the same pseudo-random order (see above). Importantly, each participant (whether an unimpaired control or Broca’s aphasic patient) was tested on each tape/list combination in a separate test session. These sessions were separated by at least two weeks, and most often by more than two weeks, so as to minimize potential exposure effects. Thus each participant saw multiple exemplars of every condition in each session, but did not receive any one sentence or visual probe word more than once per testing session. Fig. 1 gives an example of how a single sentence and its related and control visual probes would be rotated throughout the multi-tape/list conditions.

Fig. 1.

Example of tape/list counterbalancing for a test item in Experiment 1. The superscript numerals indicate the visual probe positions (digital tone on inaudible second stereo channel) in the ongoing auditory sentence (played to the participants; see text). The position of the visual probes changes across tapes, so that participants respond to the visual probe at probe position 1 in Tape 1, probe position 2 in Tape 2, etc. The related and control visual probes are counterbalanced across two lists. For this example, list one has the related visual probe ‘fighter’, and list two the control visual probe ‘climber’. Participants would get a unique tape/list combination in each test session, and would return until they had completed all of their tape/list combinations (for the unimpaired controls, the materials were counterbalanced across probe positions 1, 2, and 3; for the Broca’s patients tested in Boston, the materials were counterbalanced across probe positions 1, 2, 3, and 4; and for the Broca’s patients tested in San Diego the materials were counterbalanced across probe positions 3 and 5). Thus for this sentence in the Tape 1/List 1 combination, a participant would see ‘fighter’ at probe position one (at the offset of ‘wrestler’). In the Tape 3/List 2 combination, a participant would see ‘climber’ at probe position three (gap position). Crucially, across all 40 experimental items in a particular tape/list combination, participants would respond to some items from every condition (related vs. control visual probe at various probe positions).

As the unimpaired controls were not expected to exhibit any delay in reactivation of the antecedent at the gap position, the materials for these participants were only counterbalanced across three tape/list conditions, and only included the first 3 probe positions (PP1-antecedent, PP2-antecedent + 300 ms and PP3-gap) across six testing sessions.

For the Broca’s patients, in order to reduce the number of test sessions required to complete the experiment, not all participants were tested at all test points. The patients tested in Boston contributed data at four probe positions (PP1, PP2, PP3, and PP4). For these patients, the materials were counterbalanced across 4 tapes and 2 lists, requiring eight test sessions. The patients tested in San Diego contributed data at two probe positions (PP3 and PP5)—for these patients the materials were therefore counterbalanced across 2 tapes and 2 lists, requiring four test sessions to complete. Crucially, all of the patients contributed data to the probe position at the gap and to at least one post-gap probe position.

2.1.4. Procedure

In each session, participants were instructed on the simultaneous auditory and visual tasks, and were given considerable practice and feedback on these tasks before testing began.

For the auditory task, participants were told that they would hear a series of sentences over the headphones and that they should to listen carefully to each sentence. To encourage attention to the sentences, the experiment was paused and the participants were asked a multiple-choice question about the sentence that had just been presented (25 questions per session). These questions bore only on the setting or general topic of the sentence; and were intended only to reinforce the need for the subjects to listen to the sentences, rather than as a test of their comprehension per se. Accordingly, we did not examine or analyze the responses to these questions in any way.

Participants were also told that there would be a second, simultaneous task to perform: at some point during the auditory presentation of each sentence, they would see a string of letters appear in the center of the screen before them, and they would have to decide as quickly and accurately as possible whether the letter string formed an actual English word or not. They were instructed to indicate their decision by pressing the “yes” key for a word and the “no” key for a non-word. All participants (Broca’s patients and age-matched controls) responded with their left hand, as many of the patients exhibited right hemiparesis or weakness.

2.2. Results

Prior to analysis, it was discovered that for five sentences, the visual probes could have constituted plausible continuations of the auditory sentence for at least one probe position. All data points from these items were removed to avoid any possible confound of interpretation with respect to priming vs. integration effects (see above). Data from two additional sentences were excluded because of association of visual probes to noun phrases (other than the antecedent) in the experimental sentence.

2.2.1. Unimpaired control participants

Data from the unimpaired control participants are presented in Table 2. Response times from incorrect responses (e.g. wrong button presses or a failure to respond in the time allotted) were excluded prior to descriptive or inferential analyses (approximately 1.74%). As it is well established that neurologically intact subjects, whether young or elderly, demonstrate reactivation of the syntactically correct antecedent at the gap position (Love, 2007; Love & Swinney, 1996; Nicol & Swinney, 1989; Swinney & Fodor, 1989; Swinney & Osterhout, 1990; Tanenhaus et al., 1989; Zurif et al., 1995), for the unimpaired control group we carried out only a priori paired t-tests comparing the reaction-time data for the related and control visual probes at each probe position.

Table 2.

Results from experiment one for age-matched unimpaired controlsa

| Probe position 1 antecedent offset | Probe position 2 antecedent + 300 ms | Probe position 3 gap position | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Related visual probe | 923 (67) | 922 (130) | 896 (103) |

| Control visual probe | 960 (71) | 905 (120) | 920 (114) |

| Difference (control—related) | +37p<.05 | -17ns | +24p<.05 |

Mean response times (milliseconds) and standard errors (in parentheses) are shown for related and control visual probes at three probe positions, indicated by superscript numerals in the example sentence: “The audience liked the wrestlerii1 that the2 parish priest condemned (t)i3 for foul language.” Priming is indicated by a significant (positive) Difference between the control and related visual probes.

The results (Table 2) indicate that, as expected, the control participants primed the antecedent at probe position 1 (the offset of the antecedent; ‘control’ minus ‘related’ difference of +37 ms; t3 = 2.997, p = .015). At probe position 2 (300 ms downstream from the antecedent) no priming was observed (‘control’ minus ‘related’ difference of -17 ms; t3 = .619, p = .285). At probe position 3 (gap position), priming of the antecedent was again observed (‘control’ minus ‘related’ difference of +24 ms; t3 = 4.83, p = .004), consistent with prior published reports (see just above).

2.2.2. Broca’s aphasic patients

As with the unimpaired control participants, response times from incorrect responses were excluded prior to analysis (7.97% data loss for San Diego participants and 9.45% data loss for Boston participants). In addition, in order to reduce skewness in the distribution of patients’ responses, extreme outliers were removed on the basis of visual inspection of the normal probability plot. This led to the exclusion of responses with RTs less than 500 ms or greater than 2500 ms (approx 2.8% of the data). An additional data screen was computed to reduce item variance—for each sentence, we excluded responses greater or less than 2 standard deviations from the mean of responses for each visual probe type (related, control) at each probe position (1.25% of the data).

The remaining data were submitted to descriptive and inferential statistics. The results (Fig. 2) of a priori paired t-tests indicate that at probe position one (offset of the antecedent) there was no significant priming effect (‘control’ minus ‘related’ difference of +29 ms; t3 = -1.28, p = 0.145). However, at probe position two (antecedent plus 300 ms) there was significant priming (‘control’ minus ‘related’ difference of +57 ms; t2 = -2.76, p = 0.05).4 At probe position three (gap position) the patients again did not show a priming effect (‘control’ minus ‘related’ difference of -3 ms; t7 = .584, p = 0.29). At Probe Position four, 300 ms further downstream from the gap, patients still did not show a priming effect (‘control’ minus ‘related’ difference of +6 ms; t3 = -0.171, p = 0.437). Finally, at Probe Position five (500 ms downstream from the gap), the patients demonstrated a priming effect (‘control’ minus ‘related’ difference of +117 ms; t3 = -3.29, p = 0.02).

Fig. 2.

Mean response time (milliseconds) for Broca’s aphasic patients for sentences presented at a normal rate of speech across all five visual probe positions in experiment one.

In order to assess whether the absence of a priming effect at probe position 4 or the presence of a priming effect at probe position 5 reflected a change from the prior probe position (PP3 and PP4, respectively), the mean response times described above were submitted to post-hoc inferential statistics. These post-hoc comparisons revealed that there was no change in the priming effect between probe position 3 (gap position) and probe position 4 (300 ms later), as indicated by a non-significant Fisher’s protected least significant difference (PLSD) test: critical difference = 298.37, p = .1146. There was, however, a significant change in the pattern of priming effects between probe position 4 (300 ms after the gap) and probe position 5 (500 ms after the gap), consistent with reactivation of the antecedent that was delayed until probe position 5: Fishers PLSD, critical difference = 344.53, p = .0063. Note that the omnibus 5 (probe position) × 2 (visual probe type) ANOVA that these post-hoc analyses derive from indicated only a significant main effect of probe position (F(4, 36) = 3.217, p = 0.02).

Finally, it is important to note that the lack of priming at the trace position (probe position 3) cannot be attributed to the fact that patients were tested at two different test locations (San Diego and Boston). Patients tested at the two locations did not differ in their mean response time differences to the related and control visual probes at the gap position (PP3; post-hoc unpaired t-test, t6 = -.694, p = 0.514; Fig. 3) although it is noted that the San Diego patients were slower in their overall reaction times (Fisher’s PLSD, critical difference = 342.266, p = .008).

Fig. 3.

Demonstration of non-significant difference in priming effects between patient groups (which were non-significant for each patient group) in experiment one at probe position 3 (gap position) for the patients tested in Boston compared against those tested in San Diego.

3. Experiment 2. Gap-filling with slowed speech input

Experiment 2 provides an important complementary test of our hypothesis that slow lexical activation underlies the syntactic processing problem in Broca’s aphasia. In this study, we examine whether Broca’s patients can establish syntactically-governed dependency relations—whether they can reactivate moved constituents at gap sites—when sentences are spoken more slowly than normal. That is, does slowed speech facilitate gap-filling in Broca’s aphasic patients, enabling the formation of syntactic dependencies in the face of slow lexical activation (Love et al., 2001; Swinney et al., 1999).

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants

For this study, nine Broca’s aphasic patients (age at time of testing: 40-68; mean: 53.6 years; Table 1a) were tested at The University of California, San Diego and six neurologically unimpaired control participants (age at time of testing: 66-75; mean: 72.2 years; Table 1b) were tested at The Aphasia Research Center at the Boston Veterans’ Administration Medical Center. All participants were paid $15 per session for their participation in this study. Participant selection criteria for both aphasic and control groups were the same as for Experiment 1. Data from one patient (HB) was excluded prior to analysis, as he made predominantly (incorrect) “word” responses for the non-word visual probes.

3.1.2. Materials and design

The materials from Experiment 1 were digitally modified via Cool Edit Pro© software (Syntrillium Software) so that the rate of speech of the auditory sentences was slowed to 3.4 syllables per second, notably slower than the normal speech rate of 4-6 syllables per second (Radeau, Morais, Mousty, & Bertelson, 2000; van Heuven & van Zanten, 2005; Ziegler, 2002). Speech at this rate was perceived by unimpaired college students as sounding ‘normal’ but ‘slowed’ or ‘tired’. The materials and design were otherwise identical to those from experiment one, except that only three probe positions were examined.

The audience liked the wrestleri that the1 parish priest condemned (t)i2 for foul3 language.

Probe position 1 was 500 ms before the offset of the verb, and served as a baseline probe position, where no priming was expected for either the Broca’s patients or the unimpaired controls. Probe position 2 was at the gap position, and probe position 3 was 500 ms after the gap. Accordingly, the materials were counterbalanced across 3 tapes/2 lists, and all participants completed the experiment in six test sessions.

3.1.3. Procedure

The procedure was the same as described in Experiment 1.

3.2. Results

Prior to analysis, data from the same seven sentences identified in experiment one as problematic were removed from all analyses.

3.2.1. Unimpaired control participants

Prior to analysis, response times from incorrect responses were excluded (1% of the data). At each probe position, mean response times (by subjects) for the related and control visual probes were compared by a priori paired t-tests (p-values reported one-tailed). The results (Table 3) indicate that there was a priming effect at probe position three (control minus related difference of +46; t5 = -2.11, p = 0.04); but not at probe position one (control minus related difference of -2; t5 = 0.099, p = .46) or probe position two (control minus related difference of -24; t5 = 1.25, p = .133). This pattern is consistent with prior results indicating that slowing the rate of speech input disrupts the normally automatic processing of syntactic dependencies in unimpaired young adults (Love et al., 2001). It is also in line with evidence that time-expanded sentence input tends to be detrimental to off-line comprehension in older adults (Vaughan, Furakawa, Balasingam, Mortz, & Fausti, 2002).

Table 3.

Results from Experiment 2 for Broca’s patients and unimpaired controlsa

| Probe position 1 Baseline | Probe position 2 GAP position | Probe position 3 500 ms post GAP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age-matched controls (n = 6) | |||

| Related visual probe | 937 (37) | 926 (53) | 896 (45) |

| Control visual probe | 935 (34) | 902 (45) | 920 (46) |

| Difference (control—related) | -2ns | -24ns | +46p<.05 |

| Broca’s patients (n = 8) | |||

| Related visual probe | 1191 (134) | 1170 (129) | 1171 (136) |

| Control visual probe | 1195 (133) | 1246 (138) | 1218 (143) |

| Difference (control—related) | +4ns | +76p<.05 | +47p<.05 |

Mean response times (milliseconds) and standard errors (in parentheses) are shown for related and control visual probes at three probe positions, indicated by superscript numerals in the example sentence: “The audience liked the wrestleri that the1 parish priest condemned (t)i2 for foul3 language.” Priming is indicated by a significant (positive) difference between the control and related visual probes.

3.2.2. Broca’s aphasic patients

Data were analyzed using a mixed-effects regression model, with crossed random effects of subject and sentence, and fixed effects of probe position (1, 2, 3) and visual probe type (related vs. control). All incorrect responses (as defined in experiment one) were excluded prior to analysis (4.6% of the data). In order to reduce skewness in the distribution of responses, extreme outliers were removed on the basis of visual inspection of the normal probability plot (responses with RTs less than 500 ms or greater than 2500 ms; 2.3% of the data). An additional data screen was computed to reduce item variance—for each sentence, we excluded responses greater or less than 2 standard deviations from the mean of responses at each probe position for each visual probe type (2.3% of the data). F-statistics are reported for main effects and interactions, and t-statistics for planned comparisons of related vs. control target type differences. All p-values from t-statistics are reported one-tailed. Data from PP1 and PP2 were analyzed in one regression model (to allow for an interaction; see below); data from PP3 were analyzed separately. In all analyses, degrees of freedom were computed using the Satterthwaite approximation (Satterthwaite, 1946). Note that the degrees of freedom are large because they are based on the number of data points in these regression models, not the number of subjects or items. For similar analyses in a different patient population, see Walenski, Mostofsky, and Ullman (2007). For further discussion of these methods of analysis, see Baayen (2004, 2007).

The results for the patients (Table 3) indicate no priming at probe position one (‘control’ minus ‘related’ difference of +4 ms; t917 = .026, p = 0.40), but significant priming at probe position two (‘control’ minus ‘related’ difference was +76 ms; t917 = 2.97, p = 0.001). In addition, a significant priming effect was also seen at probe position three (‘control’ minus ‘related’ difference was +47 ms; t439 = 1.85, p = 0.035). This last effect likely indicates residual activity from the reactivation of the moved constituent at position 2.

Of central concern to this study was the hypothesis that the speed manipulation would cause a change in the pattern of priming between probe position 1 (baseline) and probe position 2 (gap position), thus demonstrating a normal pattern of syntactic reactivation in the Broca’s patients. Importantly, interaction between probe position (PP1 vs. PP2) and visual probe type (related vs. control) was significant (F(1, 917) = 3.65, p = .056; Fig. 4), consistent with the claim of ‘normal’ reactivation of the antecedent at the trace position.

Fig. 4.

Mean response time (milliseconds) for Broca’s aphasic patients for sentences presented at a slow rate of speech at baseline and gap probe positions (PP1, PP2) in experiment two.

4. Experiment 3. Effect of slowed rate of input on off-line comprehension

This experiment shifts the focus from on-line behavior to off-line comprehension. Specifically, we use a sentence-picture matching task (the SOAP: Subject-relative, Object-relative, Active and Passive; Love & Oster, 2002) to assess the Broca’s patients’ comprehension of non-canonically structured sentences, including sentences with object relative clauses, and normal and slow rates of speech. Our aim here is to examine whether a slowed rate of speech input improves success not only with respect to automatic, real-time gap-filling processes, but also with respect to off-line comprehension.

4.1. Methods

4.1.1. Participants

Eight Broca’s aphasic patients (age at testing: 50-82 years; mean: 60.5 years) and 10 neurologically unimpaired controls (matched to the patients on age; age at testing: 47-76 years; mean: 64.4 years) participated in the study. All participants were tested at The University of California, San Diego and were paid $15 per session. Participant selection criteria for both aphasic and control groups followed those described in Experiment 1 above.

4.1.2. Materials

The SOAP test consists of four kinds of sentence structures (Fig. 5): active sentences, sentences containing subject relative clauses (subject relatives), passive sentences, and sentences containing object relative clauses. The former two sentence types have canonical structures—that is, the order of the arguments in the sentence follows the canonical agent-verb-patient order typical of English—while the latter two have non-canonical structures, in which the patient argument precedes the verb. Each sentence is presented with three pictures, only one of which is a correct depiction of who’s doing what to whom in the sentence (i.e., which argument is the agent and which the patient). There are 10 exemplars for each sentence type, giving rise to a total of 40 experimental items. All sentences are equated for length, such that actives, passives, subject and object relative sentences contain approximately 11 words each. In addition, 5 practice sentences consisting of active and subject relative constructions are given at the beginning of each session to ensure the participants understand and can perform the task. Further details on the materials can be found in Love and Oster (2002).

Fig. 5.

An example stimulus from the SOAP battery. This same picture would be shown to participants four times over the course of each test session, once with an active sentence (The man in the red shirt pushes the little boy.), once with a subject relative sentence (The man that pushes the boy is wearing a red shirt.), once with a passive sentence (The man in the red shirt is pushed by the boy.), and once with an object relative sentence (The man that the boy pushes is wearing a red shirt.). For the active and subject relative sentences (“canonical” sentence structures), the correct response is the top picture. For the passive and object relative sentences (“non-canonical” sentence structures) the correct response is the bottom picture. The order of sentences and expected responses is counterbalanced across items to minimize a reliance on strategies by the participants.

For the present experiment, the sentences were recorded by a female native English speaker at a normal speech rate (approx 5.5 syllables/second). The sentences were then digitally slowed to 3.8 syllables per second (just slower than normal) via speech editing software (Cool Edit Pro©, Syntrillium Software), without affecting the comprehensibility of the sentences (as rated by 10 naïve judges).

Participants completed the experiment over two test sessions. In one session, the rate of presentation of the SOAP materials was at normal speed; at the other session the rate was at slow speed. All of the SOAP materials (i.e., including all exemplars of all four sentence types) were presented to participants during each visit. As in experiments one and two, there was a minimum of two weeks between test sessions, to minimize exposure effects.

4.1.3. Procedure

During the SOAP test, participants listen to each sentence, and point to the picture that they think best represents the meaning of the sentence. For further details about the presentation and procedures of the SOAP, see Love and Oster (2002). The presentation of slowed and regular rates was counterbalanced for the unimpaired control participants. However, as the Broca’s patients had been participating in research protocols at the UCSD laboratory for some time, they had previously been administered the SOAP task (at a regular speech rate) as a diagnostic task, in some cases 1 or 2 years prior to the running of this experiment (see Love & Oster, 2002 for more information about SOAP as a diagnostic tool). For this reason, Broca’s patients were first administered the slowed version of the SOAP, and then given the regular rate version of the task, on a second visit (again, with a minimum of two weeks between testing sessions). We compared the performance of the initial test scores (from when the patients entered the laboratory) to the current performance (reported below), and verified that each patient indeed had a stable pattern across the two administrations of the SOAP at a regular speech rate.

4.2. Results

The results indicate that at normal rates of speech, neurologically unimpaired control participants had little difficulty with the task (Table 4)—getting 98% of the canonically structured sentences correct and 99% of the non-canonically structured sentences correct. In contrast, Broca’s aphasic patients demonstrated spared performance on canonical structures but poorer (near chance) performance on non-canonical structures, consistent with the pattern that has been reported for them in the literature many times (see above).

Table 4.

Mean percent correct for Broca’s patients and age-matched controls for canonical and non-canonical sentence structures of the SOAPs assessment at both regular and slowed rates of speecha

| Canonical sentence structure |

Non-canonical sentence structure |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | Slow rate | Regular rate | Slow rate | |||

| Broca’s patients (n = 8) | 81% | ↔ | 80%ns | 61% | 71%* | |

| (Standard error) | (8.3) | (7.1) | (11.3) | (9.9) | ||

| Age-matched controls (n = 10) | 98% | ↔ | 99%ns | 99% | 97%* | |

| (Standard error) | (1.1) | (0.67) | (0.67) | (1.1) | ||

Bidirectional solid arrows indicate non-significant effects in the comparison of performance at regular vs. slow rate of speech. Unidirectional dashed arrows indicate significant effects in the comparison of performance at regular vs. slow rate of speech, pointing in the direction of better performance.

p < 05.

At the slow speech rate however, neither the unimpaired controls nor the Broca’s participants showed any detrimental effect on their performance for the canonical structures, compared to their performance on these structures at normal speed (Table 4). However, at the slowed rate of speech the groups’ patterns diverged for the non-canonical structures (Table 4). The unimpaired controls did worse on these structures at slow speed than normal speed—a decline in performance that was statistically reliable (one-tailed paired comparison, t9 = 1.809, p = .05).5 By contrast, the Broca’s patients benefited from the slowed speech input, improving to 71% percent accuracy from 61% accuracy. This change was also statistically reliable (one-tailed paired comparison, t7 = -1.965, p = .045). To be sure, 71%, although a significant improvement, is less-than-normal. But the symptom complex of Broca’s aphasia may involve processing limitations that far exceed the disruption to mechanisms involved in the real-time formation of syntactic dependencies; and presumably these other limitations could adversely affect performance on this task, despite improvements in performance due to the slowed input.

Note that an omnibus ANOVA examining main effects and interactions of the factors rate of presentation (normal vs. slow), canonicity (canonical vs. non-canonical) and participant group (patient vs. control) revealed a main effect of participant group (F(1, 64) = 35.535, p < .0001) and a marginal effect of canonicity (F(1, 64) = 3.193, p = .079), but no other main effects or interactions.

5. Discussion

The data met our expectations. When the sentences were spoken at a normal rate, the Broca’s patients showed both delayed lexical activation when encountering moved constituents and delayed reactivation of these constituents at their gap sites. This delay in reactivation confirms both our earlier findings (Love et al., 2001) and the data presented by Burkhardt et al. (2003); and, of course, it attests to the disruption of the normal formation of a syntactic dependency. By contrast, when presented with a slower-than-normal rate of speech input and, therefore, a longer lasting trace site, the patients did show reactivation at the gap. Trace sites are therefore not immutable barriers for Broca’s patients, at least not when the normal time constraints for reactivation are relaxed. Moreover, when non-canonically structured sentences were spoken at a slower rate, the Broca’s patients also showed a significant improvement in their comprehension on our sentence-picture matching task.

Our finding that gap-filling occurred for Broca’s patients and that their comprehension improved for sentences spoken at a slower-than-normal rate serves to explain an apparent contradiction recently entered in the literature. Based on evidence from eye-tracking analyses, Dickey and colleagues (Dickey & Thompson, 2006; Dickey, Choy, & Thompson, 2007) conclude that Broca’s patients have no problem in gap-filling to begin with—that is, that they fill gaps in a normally timely fashion. But an examination of their methodology reveals that they presented sentences with an input rate of approximately 3.3 syllables per second. And this corresponds, not to a normal input rate, but to the rate of our slowed speech condition—indeed, even slightly slower than that in our slowed-down condition. So, inadvertently, and contrary to their claim, they’ve shown what we’ve shown—namely, that Broca’s do form syntactic dependencies on-line when the input accommodates their slower-than-normal lexical rise time. We reiterate however, that those findings in no way demonstrate “normal” gap-filling in Broca’s patients with sentences presented at a normal rate of speech as the rate was clearly outside the standard boundary. Consistent with this conclusion is the fact that the Broca’s patients in their study showed off-line comprehension scores for non-canonical sentences that were nearly identical to those we found for our slowed down presentation (approximately 70%).

5.1. The effect on sentence comprehension of late gap-filling

We feel fairly confident, therefore, that our data are in line with Grodzinsky’s (1986, 2000, 2006) generalization that chance performance in the Broca’s patients’ comprehension of normally spoken non-canonical sentences is the result of a problem in the linking of moved constituents and their traces. But having offered an account in processing terms—in terms of an alteration in processing speed—we form a different perspective from Grodzinsky’s with respect to the consequences of this syntactic linking problem.

Grodzinsky claims that because the syntactic dependency is not formed, the patient confusingly constructs an interpretation in which the non-canonical sentence contains two agents: One agent is the consequence of grammatical assignment by the verb. The other agent is the consequence of the non-grammatical agent-first heuristic being inappropriately applied to the unassigned moved constituent—i.e., to the constituent that has not been normally linked to its trace site. Our work changes this account. Since we show that the syntactic link is eventually formed, however slow, we document a circumstance that adds to the Broca’s patient’s interpretive burden. Not only does the patient represent non-canonical sentences as having two agents, but in addition s/he represents the moved constituent as both the agent of the action and, later, when the dependency is finally constructed, as the entity-acted-upon. This leads to even more representational confusion and the need to guess on a sentence-picture-matching task.

5.2. Slowed lexical access vs. slowed syntax

Our data emphasize that lexical access, the basis for syntactic processing and indeed for processing at all levels, is slow following left anterior brain damage. Equally, the data indicate that the adverse effect of a temporal prolongation of lexical access is felt only when because of it the failure to create a syntactic link in time allows the confusing entry of a non-grammatical strategy. By contrast, Burkhardt et al. (2003), argue that delayed gap-filling is the result of a general slowing only of syntactic operations (see also Haarmann & Kolk, 1991), and that once finally formed, the syntactic structure that Broca’s patients construct is indistinguishable from that built by the intact brain. If so, the “slow-syntax” hypothesis cannot on its own explain why sentences that feature constituent movement are understood less well than those that don’t. To accomplish this, the hypothesis needs to incorporate conflicting operations—conflict of the sort introduced by the intrusion of the agent-first strategy, for example, or conflict between syntactic and semantic linking mechanisms as proposed by Piñango (2000), or inappropriate competition between syntactic and discourse operations as hypothesized in Avrutin’s (2006) model of “weak syntax.”

However, even with any one of these additions, the “slow-syntax” hypothesis still falls short. Having tested only for reactivation (at and around the gap site), and not for initial activation of the antecedent, Burkhardt et al. (2003) miss the point that not just syntactically licensed lexical reactivation at the gap site is delayed, but that lexical activation, in general, is abnormally slow during sentence processing in Broca’s aphasia. They therefore miss an important generalization: namely, that damage to left anterior cortex alters a basic processing parameter—speed of lexical access during sentence comprehension—without necessarily honoring distinctions within and between abstract levels of linguistic representation. In the light of this generalization, the formation of a syntactic dependency involving a moved constituent is selectively vulnerable, not because it’s a syntactic operation, but because if lexical reactivation is not accomplished within a normal time frame, a non-grammatical heuristic kicks in to provide a conflicting interpretation. So in the view we present here, the basic change following left anterior brain damage is the timing of lexical information activation.

This perspective also has particular relevance for thinking about the variability that Broca’s patients show in their comprehension of non-canonically structured sentences. It is highly unlikely that speed of lexical activation will be diminished by precisely the same amount for each Broca’s patient. So there is a clear basis for some variability in their comprehension data and even for expecting some outliers. But though this processing variability plays a role in shaping the distribution of comprehension scores across subjects, the fact remains that Broca’s patients, as a group, perform at chance level for non-canonical structures (Drai & Grodzinsky, 2006a, 2006b).

We think that our focus on lexical timing also captures a generalization about normal as well as abnormal sentence processing. In particular, we think that the performance disruptions of our neurologically intact subjects when faced with slowed-down non-canonical sentences—their abnormal gap-filling and less accurate comprehension—are also accountable in terms of a mismatch between lexical activation speed and the temporal demands imposed by syntactic processing. So in a complete reversal of the circumstances influencing aphasic comprehension, normal lexical rise time (control subjects) may cause problems for the comprehension of sentences delivered at a slowed speed, just as slow lexical rise time (aphasic patients) appears to cause problems for the comprehension of sentences delivered at a normal rate of speech—the control subjects may be unable to accommodate the slower unfolding of the sentence to the rapidity of their lexical activation. That is, the slowed-down input may disrupt the reflexive quality of gap-filling such that the unimpaired listeners have the time to form unhelpful competing strategies and hypotheses. When there is a match between the speed of lexical activation and sentence input speed, performance is better (for both patients and controls) than when there is a mismatch.

The claim that left anterior brain damage diminishes lexical activation speed holds up equally well when considering compositional semantic processing—in particular, the accessing of potential argument structure configurations as well as aspectual coercion and complement coercion. None of these sentence-level semantic operations are adversely affected by the Broca’s slower-than-normal word activation pattern (Piñango & Zurif, 2001; Shapiro & Levine, 1990; Shapiro, Gordon, Hack, & Killackey, 1993). And for good reason: The semantic operations are, themselves, normally slower to develop and longer lasting than syntactic operations (McElree & Griffith, 1995; Piñango, Winnick, Ullah, & Zurif, 2006). That is, they are less temporally demanding—they accommodate slower lexical activation than does the formation of a syntactic dependency.

5.3. The functional commitment of left inferior frontal cortex

Using data from aphasia to study functional neuroanatomy does not permit elaboration concerning the entire neural network supporting any particular process. Still, within the left-sided perisylvian cortical language region, we can be fairly certain that the anterior area implicated in Broca’s aphasia plays a role in sustaining processing speed—and the syntactic operations dependent upon such speed—that is not played by the temporoparietal area associated with Wernicke’s aphasia. Thus, in contrast to Broca’s patients, Wernicke’s patients show normal speed patterns with respect to both initial lexical activation on the list priming paradigm (Prather et al., 1997) and gap-filling (Swinney et al., 1996; Zurif et al., 1993). We are not claiming by this that their rapid activation of word forms leads to normally elaborated word representations; nor are we claiming that their gap filling is structurally constrained in the normal manner. Indeed, to enter the standard caveat, even the data we have already gained need replication. But as it stands, our Broca-Wernicke comparisons do suggest a unique functional commitment of left anterior cortex to initial lexical rise-time parameters.

That said, however, it is not clear that the term “lexical activation” should even be a primitive expression in our explanation of the role of left anterior cortex. We can claim only that the term describes a real consequence of left anterior brain damage and that it accounts for the syntactic limitation. Slow lexical activation, itself, however, may possibly turn out to be explicable in terms of more basic aberrations of processing and activation, whether these aberrations involve dynamics of any network of information, linguistic or otherwise, or whether they implicate only networks composed of linguistically-specific formats. (See Avrutin (2006) and Blumstein & Milberg (2000) for discussions along these lines.)

Furthermore, it is not likely that the role of left anterior cortex in syntactic comprehension has only to do with processing speed. This cortical region has also been shown to sustain various forms of memory (e.g., Smith & Geva, 2000) and memory constraints are certainly implicated in the real-time formation of syntactic dependencies—some sort of buffer must exist in order to hold a moved constituent in memory until a gap is found and a link formed. (See Cooke et al. (2001) for data on left inferior frontal area activation patterns as a function of the amount of information to be held in the buffer during sentence processing). These memory demands likely add to the Broca’s patients’ processing burden. Indeed the extra work required to maintain a temporary buffer explains our finding that although both lexical activation and reactivation are significantly delayed during the course of sentence processing, the latter is delayed even more than the former.

Given the data presented here, then, it seems quite clear that syntactic limitations stateable in the abstract terms of linguistic theory can be connected to changes in cortically localizable processing resources. This means that descriptions of language localization in the brain can be offered in terms of speed of activation and storage capacity—in terms, that is, of processing resources that intuitively feel “wired in.” To be more exact, the left anterior cortical region associated with Broca’s aphasia appears crucially involved in the reflexive formation of syntactically-governed dependency relations, not because it’s the locus of specific syntactic representations per se, but rather because it sustains the real time implementation of these specific representations by supporting, at the least, a lexical activation rise-time parameter (as we have focused upon here) and some form of working memory.

Footnotes

Neuroimaging analyses of normal sentence processing have sought to provide greater precision on this matter. Several studies suggest that the frontal cortical region for syntax incorporates only the inferofrontal gyrus—BA44 and BA45 (Ben-Shachar, Hendler, Kahn, Ben-Bashat, & Grodzinsky, 2003; Caplan, Alpert, & Waters, 1998; Dapretto & Bookheimer, 1999; Stromswold, Caplan, Alpert, & Rauch, 1996). But not all studies have shown this particular focus of activation. For instance, Cooke et al. (2001) have observed recruitment, not of BA44 or of BA45, but of BA47 in their fMRI analysis of syntactic processing. Even in the same laboratory, even for the same underlying syntactic operation, BA44 and/or 45 are not invariably activated. (See Caplan, 2000 for a discussion of these inconsistencies.) Moreover, it is not clear that efforts to achieve such fine-grained localization on the basis of neuroimaging are warranted even in principle. Interindividual variation in the language regions is great no matter what anatomical mapping method is used (e.g., Amunts & Zilles, 2006; Petrides, 2006). In addition, Amunts, Zilles, and their colleagues have shown that the sulcal contours defining BA 44 and 45 are not reliable landmarks of cytoarchitectonic borders (e.g., Amunts & Zilles, 2006; Amunts et al., 1999). Even so there is clearly both greater precision and a much wider view provided by neuroimaging. And because of this wider view—because neuroimaging studies are lesion independent—the total activation patterns they reveal for particular syntactic operations can, in principle, be compared with the lesion sites known to disrupt such operations, thereby distinguishing those sites that are crucially involved and those that play participatory roles.

Priming refers to the fact that lexical decisions are faster for target words when they are immediately preceded by semantically related words than when preceded by unrelated words. This difference is taken to mean that the preceding word—the priming word—has been activated and that this activation, having spread within a semantic/associative network including the target, has lowered the target’s recognition threshold (e.g., Meyer, Schvaneveldt, & Ruddy, 1975).

One patient did not ultimately contribute any data points at this probe position.

We note that while there is a decrease in participant performance, overall, the unimpaired group does perform very well on this task.

The work reported in this paper was supported primarily by NIH Grant DC 02984 with additional support from NIH Grant DC 03660, DC000494 and NIH Grant DC005207. We thank Dr. Penny Prather and Dr. Nick Nagel for their help in constructing stimuli and in formulating the experimental design, and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

References

- Alexander M, Naeser M, Palumbo C. Broca’s area aphasias: Aphasia after lesions including the frontal operculum. Neurology. 1990;40:353–362. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunts K, Schleicher A, Burgel U, Mohlberg H, Uylings H, Zilles K. Broca’s region revisited: Cytoarchitecture and intersubject variability. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1999;412:319–341. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990920)412:2<319::aid-cne10>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunts K, Zilles K. A multimodal analysis of structure and function in Broca’s region. In: Grodzinsky Y, Amunts K, editors. Broca’s region. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Avrutin S. Weak syntax. In: Grodzinsky Y, Amunts K, editors. Broca’s region. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Baayen HR. Statistics in psycholinguistics: A critique of some current gold standards. Mental Lexicon Working Papers 1. 2004;1:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Baayen HR. Analyzing linguistic data: A practical introduction to statistics. Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shachar M, Hendler T, Kahn I, Ben-Bashat D, Grodzinsky Y. The neural reality of syntactic transformations: Evidence from fMRI. Psychological Science. 2003;14.5:433–440. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson DF. Aphasia. In: Heilman K, Valenstein E, editors. Clinical neuropsychology. Oxford University Press; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bever T. The cognitive basis of linguistic structures. In: Hayes JR, editor. Cognition and the development of language. Wiley; New York: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein SE, Katz B, Goodglass H, Shrier R, Dworetzky B. The effects of slowed speech on auditory comprehension in aphasia. Brain and Language. 1985;24:246–265. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(85)90134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein S, Milberg W. Language deficits in Broca’s and Wernicke’s aphasia: A singular impairment. In: Grodzinsky Y, Shapiro L, Swinney D, editors. Language and the brain: Representation and processing. Academic Press; San Diego: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt P, Piñango M, Wong K. The role of the anterior left hemisphere in real-time sentence comprehension: Evidence from split intransitivity. Brain and Language. 2003;86:9–22. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(02)00526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D. Positron emission tomographic studies of syntactic processing. In: Grodzinsky Y, Shapiro L, Swinney D, editors. Language and the brain: Representation and processing. Academic Press; San Diego: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D, Alpert N, Waters G. Effects of syntactic structure and propositional number on patterns of regional cerebral blood flow. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1998;10:541–552. doi: 10.1162/089892998562843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky N. Lectures on government and binding. Foris; Dordrecht: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke A, Zurif EB, DeVita C, Alsop D, Koenig P, Detre J, et al. Neural basis for sentence comprehension: Grammatical and short-term memory components. Human Brain Mapping. 2001;15:80–94. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]