Abstract

For the development of blood-stage malaria vaccines, there is a clear need to establish in vitro measures of the antibody-mediated and the cell-mediated immune responses that correlate with protection. In this study, we focused on establishing correlates of antibody-mediated immunity induced by immunization with apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA1) and merozoite surface protein 142 (MSP142) subunit vaccines. To do so, we exploited the Plasmodium chabaudi rodent model, with which we can immunize animals with both protective and nonprotective vaccine formulations and allow the parasitemia in the challenged animals to peak. Vaccine formulations were varied with regard to the antigen dose, the antigen conformation, and the adjuvant used. Prechallenge antibody responses were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and were tested for a correlation with protection against nonlethal P. chabaudi malaria, as measured by a reduction in the peak level of parasitemia. The analysis showed that neither the isotype profile nor the avidity of vaccine-induced antibodies correlated with protective efficacy. However, high titers of antibodies directed against conformation-independent epitopes were associated with poor vaccine performance and may limit the effectiveness of protective antibodies that recognize conformation-dependent epitopes. We were able to predict the efficacies of the P. chabaudi AMA1 (PcAMA1) and P. chabaudi MSP142 (PcMSP142) vaccines only when the prechallenge antibody titers to both refolded and reduced/alkylated antigens were considered in combination. The relative importance of these two measures of vaccine-induced responses as predictors of protection differed somewhat for the PcAMA1 and the PcMSP142 vaccines, a finding confirmed in our final immunization and challenge study. A similar approach to the evaluation of vaccine-induced antibody responses may be useful during clinical trials of Plasmodium falciparum AMA1 and MSP142 vaccines.

Infection with the protozoan parasites Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax causes 300 million to 500 million clinical episodes of malaria annually (21). With at least 40% of the world's population at risk for malaria, multiple strategies are being explored to reduce this global public health problem. Progress continues to be made in the development of malaria vaccines for potential use in areas where malaria is endemic (18, 28). It is encouraging that in a recent trial, the rate of severe malaria was significantly reduced in young children in Mozambique immunized with RTS,S, a P. falciparum preerythrocytic-stage vaccine (1); and it was found that RTS,S was safe, immunogenic, and efficacious in infants (1 to 3 months of age) (3). For blood-stage vaccines, the testing of vaccine safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy in human subjects has moved forward for two candidate antigens, namely, apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA1) (15, 31, 42) and merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP1) (30, 35, 47, 49, 56).

Both AMA1 and MSP1 are expressed on the surface of extracellular, invasive merozoites and are essential for blood-stage parasite growth (17, 36, 50). We do not fully understand the precise functions of AMA1 and MSP1 in this invasion process, but their roles do appear to be distinct and nonoverlapping. The basic strategy for AMA1- and MSP1-based vaccines is the induction of antibodies that neutralize the merozoites released upon schizont rupture. The mechanisms of action of such neutralizing antibodies may include the blocking of key receptor-ligand interactions, inhibition of the proteolytic processing steps required for the invasion of erythrocytes (RBCs), as well as the opsonization and/or agglutination of parasites. In both in vitro and in vivo studies, antibodies against MSP1 (4-8, 13, 14, 22, 25, 27, 29, 37, 45) and AMA1 (2, 4, 5, 11, 12, 48) effectively neutralized merozoites of homologous parasite strains and provided protection against blood-stage malaria.

As the development and testing of AMA1- and MSP1-based vaccines advanced, the need to identify measurable parameters of the vaccine-induced immune responses that predict protection became a priority. One obstacle to defining such correlates has been the lack of data for a cohort of human subjects who were immunized with AMA1- or MSP1-based vaccines and who were protected to some degree against P. falciparum malaria. Nevertheless, the use of the in vitro P. falciparum growth inhibition assay (GIA) did emerge as one surrogate assay that could be used to measure the parasite-neutralizing activities of vaccine-elicited antibodies in nonhuman primates (45). While the assay has been standardized and provides some useful information, it is still imperfect. The GIA measures immunoglobulin G (IgG) activity in the absence of other components of the immune system, such as complement and Fc-bearing phagocytes, that may be important (33). As such, the GIA cannot mimic the complex host-parasite interactions that occur in the in vivo environment and that collectively influence vaccine efficacy and infection outcome.

The Plasmodium yoelii and Plasmodium chabaudi rodent models of malaria provide an opportunity to define correlates of AMA1 and/or MSP1 vaccine-induced protection (2, 4-6, 12, 13, 22). With these models, we can effectively measure vaccine efficacy, as we can allow a blood-stage infection to progress to the peak level of parasitemia in the absence of antimalarial drug treatment. This is one clear advantage of the models over immunogenicity and efficacy studies involving Aotus monkeys or human subjects. Previously, we used the P. chabaudi model to investigate the mechanisms of P. chabaudi AMA1 (PcAMA1) and P. chabaudi MSP142 (PcMSP142) vaccine-induced protection (4, 5). We showed that B cells were necessary for maximal AMA1- and MSP1-induced protection and that the efficacies of the vaccines against P. chabaudi malaria were unaffected by the absence of γδ T cells, interleukin-4, or gamma interferon. The goal of this study was to manipulate the P. chabaudi vaccine model to increase the probability of identifying correlates of protection. Building on our previous results, we immunized mice with both protective and nonprotective formulations of the PcAMA1 and PcMSP142 vaccines to induce a broad range of antibody responses that differed in both quantity and quality. In doing so, we were able to define measurable parameters of vaccine-induced antibody responses that correlated with protection against challenge infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and parasites.

Male C57BL/6 mice (age, 5 to 6 weeks) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Plasmodium chabaudi adami 556KA, hereafter referred to as P. chabaudi, was maintained as cryopreserved stabilates. Blood-stage infections were initiated by the intraperitoneal injection of 1 × 106 washed, parasitized RBCs obtained from donor mice. The resulting infections were monitored by enumerating the parasitized RBCs in thin smears of tail blood stained with Giemsa. Tail blood smears were prepared daily during the acute phase of infection, and the results are expressed as the percent parasitemia, which was calculated as the (number of parasitized RBCs/total number of RBCs) × 100. Throughout these studies, routine screening of sentinel mice was conducted to ensure that the colony remained specific pathogen free.

Recombinant antigens.

Recombinant PcAMA1 (rPcAMA1) and recombinant rPcMSP142 (rPcMSP142) were produced by using a pET/T7 RNA polymerase bacterial expression system with the pET-15b plasmid vector and Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)(pLysS) as the host strain (Novagen, Madison, WI). The 54-kDa rPcAMA1 protein encompasses the large ectodomain of P. chabaudi AMA1. The rPcMSP142 antigen contains the C-terminal portion of MSP1 minus the hydrophobic anchor sequence. Both recombinant proteins contain 20 plasmid-encoded N-terminal amino acids which include a 6-residue histidine tag to facilitate purification by nickel chelate affinity chromatography. The expression, purification, and refolding of rPcAMA1 and rPcMSP142 have previously been described in detail (4, 5). Alternatively, rPcAMA1 and rPcMSP142 were fully reduced by overnight treatment with 25 mM dithiothreitol at 4°C and were subsequently alkylated by the addition of 100 mM iodoacetic acid and incubation for 1 h at 37°C. Following dialysis, the purity and the conformation of refolded (RF) and reduced/alkylated (RA) rPcAMA1 and rPcMSP142 were confirmed by Coomassie blue staining following sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis run under reducing and nonreducing conditions.

Immunization and challenge experiments.

Groups of C57BL/6 mice were immunized subcutaneously with RF rPcAMA1 or RF rPcMSP142 in adjuvant. On the basis of the findings of our previous immunogenicity and efficacy studies (4, 5), we selected two antigen doses and two adjuvants previously shown to elicit a range of protective responses. In trial 1, the mice were immunized with 25 μg of recombinant antigen formulated with alum (Pierce Chemical Company, Rockford, IL) as the adjuvant. Immunoblot analysis indicated that ∼75% of the rPcAMA1 and >90% of the rPcMSP142 in each formulation was adsorbed to the aluminum-magnesium hydroxide matrix. In trial 2, the mice were immunized with 1 μg of recombinant antigen formulated with 25 μg of Quil A (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corporation, Westbury, NY) as the adjuvant. In trial 3, the mice were immunized with 25 μg of recombinant antigen formulated with 25 μg of Quil A as the adjuvant. In each trial, control animals were immunized with adjuvant alone. The mice were boosted twice at 3-week intervals with the same antigen-adjuvant formulation used for the primary immunization or with adjuvant alone. Two weeks after each of the three immunizations, five mice in each immunized or control group were sacrificed and their sera were collected for in vitro antibody assays (see below). Two weeks following the third immunization, the final sets of immunized or control mice in each trial (five mice per group) were challenged with 1 × 106 P. chabaudi blood-stage parasites, and the infection was monitored for 3 to 4 weeks, until complete resolution.

In vitro studies of P. falciparum and in vivo studies with animal model systems indicate that antibodies against conformational epitopes of AMA1 and MSP1 are protective (8-10, 12, 13, 22, 23, 25, 29, 37, 48). To evaluate whether the levels of prechallenge antibodies against linear and disulfide-dependent epitopes can be used as a correlate of protection, groups of C57BL/6 mice (n = 5) were immunized and boosted twice with 25 μg of RF or RA rPcAMA1 or with 25 μg of RF or RA rPcMSP142 formulated with Quil A (25 μg) as the adjuvant in trial 4. This would be predicted to induce antibody responses to a wide range of both protective and nonprotective epitopes. The control mice received Quil A alone. Small volumes of prechallenge sera were collected from each animal 8 to 10 days following the third immunization. Two weeks following the third immunization, the mice were challenged as described above with P. chabaudi blood-stage parasites and the course of infection was monitored. In trial 5, C57BL/6 mice (n = 10) were immunized and boosted twice with 25 μg of RF rPcAMA1 or RF PcMSP142 formulated with Quil A (25 μg) as the adjuvant prior to P. chabaudi challenge to test the predictive value of the correlations identified in trial 4.

Quantitation of antigen-specific IgG response.

The titers of antibodies present in sera collected 2 weeks following the primary, secondary, and tertiary immunizations with rPcAMA1 or rPcMSP142 that were reactive with RF or RA rPcAMA1 or with rPcMSP142 were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). High-binding ELISA plates (Easy-Wash; Corning Costar Corporation, Cambridge, MA) were coated with 0.25 μg/well of rPcAMA1 or rPcMSP142 diluted in 100 mM Na2CO3-NaHCO3, pH 9.6, by overnight incubation at 4°C. To determine that the levels of binding of RF and RA rPcAMA1 and rPcMSP142 to the ELISA plate wells were equivalent, the binding was monitored by measuring the reactivity with a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for the N-terminal His tag (Novagen). The wells were washed and blocked for 1 h with TBS (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl) containing 5% nonfat dry milk. The reactivity of each serum sample, serially diluted in TBS-0.1% Tween 20 containing 1% bovine serum albumin, was determined. Bound antibodies were detected by using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit antibody specific for mouse IgG (H+L; Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA) and 2,2′-asinobis(3-ethyl-benzthiazolinesulfaonic acid) (ABTS) as the substrate. For each dilution, the mean absorbance values at 405 nm (A405) of the sera from adjuvant-treated control mice (n = 5) were subtracted as the background. For each serum sample, A405 values of between 1.0 and 0.1 were plotted, and the titer was calculated as the reciprocal of the dilution of serum that yielded an A405 of 0.5. To eliminate variability between the assays, the titers were normalized on the basis of the reactivity of a standard serum sample pool that was obtained from mice (n = 5) immunized with a combination of rPcAMA1 and rPcMSP142 in Quil A as the adjuvant and that was run on each ELISA plate.

The quantity and the isotypic profile of the antigen-specific antibodies in prechallenge sera were determined by ELISA, as described previously (4, 5), by using rPcAMA1- or rPcMSP142-coated wells. Briefly, serum from each animal was assayed on antigen-coated wells at dilutions that ranged from 1:100 to 1:3,200,000. Antigen-specific antibodies were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit antibody specific for mouse IgM, IgG1, IgG2b, or IgG3 (Zymed Laboratories) or with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG2c (IgG2a b allotype; Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., Birmingham, AL) (33) and ABTS as the substrate. In each assay, wells coated with purified IgM (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) or with IgG1, IgG2b, or IgG3 (Zymed Laboratories) isotype control antibodies were used to generate standard curves (16 ng/ml to 2 μg/ml). The IgG2c standard curve was generated by using a purified monoclonal IgG2c (IgG2a b allotype) antibody (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Jose, CA). The concentration of each IgG isotype was expressed in units per milliliter, where 1 U/ml was equivalent to 1 μg of myeloma standard/ml. The values obtained with control sera from adjuvant-treated mice (n = 5) were comparable to the background values obtained with sera from naive mice (n = 5) and have been subtracted.

Measurement of antibody avidity.

Our standard ELISA for determination of the PcAMA1- and PcMSP142-specific antibody titers present in prechallenge immunization sera was modified according to the protocol of Pullen et al. (43) to estimate antibody avidity. Following the binding of antigen-specific antibodies in each serum sample to rPcAMA1- or rPcMSP142-coated wells, ammonium thiocyanate at molar concentrations of 0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, or 4.0 diluted in TBS was added to sets of wells and the plates were incubated for 15 min at room temperature. The plates were washed, and bound IgG was detected as above. The resistance of the antigen-antibody complexes to dissociation with ammonium thiocyanate was utilized as the measure of avidity. The avidity index for each serum sample was calculated as the concentration of ammonium thiocyanate necessary to reduce the binding of serum antibodies to rPcAMA1 or rPcMSP142 by 50%. The avidity index was calculated with a dilution of serum that yielded an A405 of 0.5 to 1.0 in the absence of ammonium thiocyanate.

Statistical analysis.

The statistical significance of the differences in the antibody responses and in the mean peak levels of parasitemia between the groups was calculated by analysis of variance. Correlations between in vitro measures of antibody responses and protection against P. chabaudi malaria were initially evaluated by calculation of the Pearson product-movement correlation coefficient for both nontransformed and log-transformed data (StatMost statistical analysis software; Dataxiom Software, Los Angeles, CA). In trial 4, the most significant associations were observed by using log-transformed data for PcAMA1 and nontransformed data for PcMSP142. On the basis of these positive and negative correlations, a multiple-regression analysis was performed to define an equation that could be used to predict the mean peak level of P. chabaudi parasitemia on the basis of the prechallenge antibody titers to RF and denatured (RA) PcAMA1 or PcMSP142 considered in combination. The equations were as follows: for the PcAMA1 vaccine (r2 = 0.82), log(parasitemia) = 14.48 − [2.92(log titer of RF form)] + [0.16(log titer of RA form)], and for the PcMSP142 vaccine (r2 = 0.79), parasitemia = 1.54 − [2.42 × 10−6(titer of RF form)] + [1.06 × 10−5(titer of RA form)].

RESULTS

Induction of antigen-specific antibodies by protective immunization with rPcAMA1 or rPcMSP142.

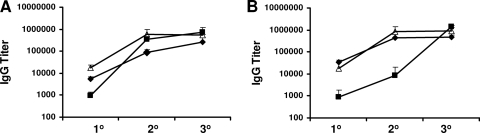

One approach that can be used to define the correlates of vaccine-induced protective B-cell responses is to elicit antibodies by immunization with distinct antigen-adjuvant vaccine formulations that provide various levels of protection against disease. Groups of C57BL/6 mice were immunized and boosted twice with RF rPcAMA1 or RF rPcMSP142 in three distinct formulations. The two antigen doses (1 μg and 25 μg) and two adjuvants (alum and Quil A) selected were previously reported to induce intermediate or high levels of protection in this vaccine model (4, 5). Mice were immunized with 25 μg of antigen formulated with alum in trial 1, with 1 μg of antigen formulated with Quil A in trial 2, or with 25 μg of antigen formulated with Quil A in trial 3. Sera were collected from sets of immunized animals that were sacrificed 2 weeks after the primary, secondary, and tertiary immunizations. The titers of antigen-specific antibodies were determined by ELISA (Fig. 1). Relatively low titers of antigen-specific antibodies were detected following a single immunization with either antigen, with the response elicited by 1 μg of antigen formulated with Quil A being significantly lower than that induced by 25 μg of antigen formulated with either Quil A or alum (P < 0.05). For PcAMA1, all responses were significantly boosted by a second immunization (P < 0.002). Only the responses induced by immunization with rPcAMA1 formulated with alum (trial 1) were boosted further by the third and final immunization (P < 0.05). Following the third immunization, however, the PcAMA1-specific antibody levels induced by immunization with 1 μg or 25 μg of antigen formulated with Quil A were high and comparable and two- to threefold greater than those induced by immunization with 25 μg of rPcAMA1 formulated with alum (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1A). The responses induced by rPcMSP142 immunization followed a similar pattern, with the antigen-specific IgG titers being significantly boosted by either a second immunization (trials 1 and 3; P < 0.01) or a third immunization (trial 2; P < 0.001). As was found with PcAMA1, the final titers of PcMSP142-specific antibodies induced by immunization with 1 μg or 25 μg of antigen formulated with Quil A were two- to threefold higher than that induced by immunization with the alum-based formulation (P < 0.03) (Fig. 1B). In the sera from mice that received a tertiary immunization, the antibody titers induced by rPcMSP142 were higher than those induced by rPcAMA1, irrespective of the adjuvant used (P < 0.05), but the differences were less than twofold.

FIG. 1.

Titers of antigen-specific IgG antibodies induced by protective immunization with rPcAMA1 or rPcMSP142. Groups of C57BL/6 mice (n = 5) were immunized three times with purified rPcAMA1 or rPcMSP142 in three distinct formulations. Each vaccine dose included 25 μg of antigen and alum in trial 1 (⧫), 1 μg of antigen and Quil A in trial 2 (▪), or 25 μg of antigen and Quil A in trial 3 (Δ). Control mice were immunized with adjuvant alone. Two weeks following the primary, secondary, and tertiary immunizations in trials 1 to 3, five animals in each immunized group were sacrificed and serum was collected for analysis of vaccine-induced antibodies. The mean IgG titers ± standard deviations of PcAMA1-specific antibodies (A) and PcMSP142-specific antibodies (B) following each immunization are shown.

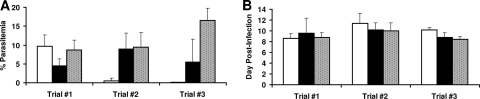

Two weeks following the third immunization, the final group of rPcAMA1- and rPcMSP142-immunized and adjuvant-treated control mice were challenged with 1 × 106 P. chabaudi-parasitized RBCs. The results from the challenge infection are shown in Fig. 2A. In trial 1, the mean peak level of parasitemia in mice immunized with RF rPcMSP142 (25 μg) was significantly reduced to 4.43% ± 1.89%, whereas it was 8.68% ± 2.66% in mice immunized with alum alone (P < 0.05). In contrast, the mean peak level of parasitemia in mice immunized with RF rPcAMA1 (25 μg) reached 9.73% ± 2.89%, which was comparable to that for the adjuvant-treated control group. The converse was true in trial 2. The mean peak level of parasitemia in mice immunized with RF rPcAMA1 (1 μg) was markedly reduced (to 0.49% ± 0.79%) compared with the level in the mice immunized with Quil A alone (9.48% ± 3.78%) (P < 0.01). However, the mean peak level of parasitemia in mice immunized with RF rPcMSP142 (1 μg) reached 8.99% ± 4.16% and was indistinguishable from that for the adjuvant-treated control group. Finally, in trial 3, the mean peak levels of parasitemia in mice immunized with RF rPcAMA1 (25 μg) or RF rPcMSP142 (25 μg) were significantly reduced (to 0.07% ± 0.03% and 5.46% ± 6.119%, respectively) compared to the level in mice immunized with Quil A alone (16.48% ± 3.25%) (P < 0.01). With the exception of these differences in the levels of parasitemia, the courses of infection in antigen-immunized mice relative to that in the adjuvant-treated control mice in each of the three trials were comparable. Infection typically peaked between days 8 and 10 postinfection, and there were no significant differences between the protected and the nonprotected groups (Fig. 2B). All animals survived and suppressed parasitemia to undetectable levels by day 18 to 20 postchallenge with P. chabaudi.

FIG. 2.

PcAMA1- and PcMSP142-induced protection against P. chabaudi malaria in trials 1 to 3. Groups of C57BL/6 mice (n = 5) were immunized three times with purified rPcAMA1 (□) or rPcMSP142 (▪) in three distinct formulations (trials 1 to 3). Control mice were immunized with adjuvant alone (░⃞). Two weeks following the third immunization, the mice were challenged with 1 × 106 P. chabaudi-parasitized erythrocytes. The resulting levels of parasitemia were monitored by enumerating the parasitized RBCs in thin smears of tail blood stained with Giemsa. The peak levels of parasitemia (means ± standard deviations) (A) and the days of the peak levels of parasitemia (mean ± standard deviations) (B) are shown for each group.

Despite the variation in the protective efficacy against P. chabaudi malaria induced by these distinct PcAMA1 and PcMSP142 vaccine formulations, the modest differences in the prechallenge IgG titers (tertiary sera) in antigen-immunized mice could not be correlated with the reduction in the mean peak level of parasitemia. In all three trials, the most dominant antibodies by far were those that recognized conformational epitopes of PcAMA1 and PcMSP142, that had comparable avidities, and that were of the IgG1 subclass (data not shown). As such, this approach did not induce antigen-specific antibodies of sufficient heterogeneity to allow measurable parameters of vaccine-induced antibody responses to be linked with the outcome of infection.

Alternative approach to identification of in vitro correlates of antibody-mediated immunity.

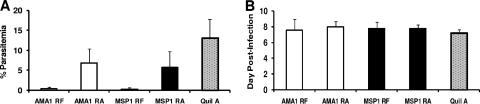

In the next series of experiments, a different approach was taken to induce a broader array of protective and nonprotective PcAMA1- and PcMSP142-specific antibody responses to improve the chances of identifying correlates of vaccine-induced immunity. Instead of using various antigen doses and adjuvants in each vaccine formulation, the state of the antigen itself was altered. In trial 4, the mice were immunized three times with 25 μg of RF or RA rPcAMA1 or with RF or RA rPcMSP142 formulated with Quil A as the adjuvant or with adjuvant alone. Two weeks following the final immunization, prechallenge sera were obtained for analysis of the antibody responses, and the mice were then challenged with P. chabaudi-parasitized RBCs. As shown in Fig. 3A, mice immunized with RF rPcAMA1 or RF rPcMSP142 were solidly protected against P. chabaudi malaria and had mean peak levels of parasitemia of 0.36% ± 0.47% and 0.24% ± 0.40%, respectively, whereas the peak level of parasitemia in the adjuvant-treated control group was 13.13% ± 4.62% (P < 0.001). In contrast, mice immunized with RA antigens were partially protected against P. chabaudi challenge infection and had only an ∼50% reduction in the mean peak level of parasitemia. The mean peak level of parasitemia in mice immunized with RA rPcAMA1 was 6.80% ± 3.55%, which was significantly lower than that in mice immunized with Quil A alone (P < 0.05) but higher than that in mice immunized with RF rPcAMA1 (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3A). Likewise, the mean peak level of parasitemia in mice immunized with RA rPcMSP142 was 5.80% ± 3.88%, which was significantly lower than that in mice immunized with Quil A alone (P < 0.03) but higher than that in mice immunized with RF rPcMSP142 (P < 0.02). As described above, the peak levels of parasitemia in all groups occurred between days 7 and 9 postchallenge (Fig. 3B), and 100% of the mice survived.

FIG. 3.

Antigen conformation influences protection against P. chabaudi malaria by PcAMA1 and PcMSP142 vaccines. In trial 4, groups of C57BL/6 mice (n = 5) were immunized three times with RF or RA rPcAMA1 (□) or with RF or RA rPcMSP142 (▪) formulated with Quil A as the adjuvant. Control mice were immunized with adjuvant alone (░⃞). Two weeks following the third immunization, the mice were challenged with 1 × 106 P. chabaudi-parasitized erythrocytes. The resulting levels of parasitemia were monitored by enumerating the parasitized RBCs in thin smears of tail blood stained with Giemsa. The peak level of parasitemia (mean ± standard deviation) (A) and the day of the peak level of parasitemia (mean ± standard deviation) (B) are shown for each group.

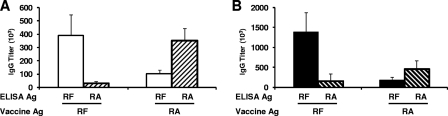

The titer and specificity of vaccine-induced antibodies for disulfide-dependent B-cell epitopes of PcAMA1 and PcMSP142 were measured by ELISA (Fig. 4). For RF rPcAMA1- and RA rPcAMA1-immunized mice, the overall titers of antibodies present in prechallenge sera were not significantly different when the titers against the immunizing antigen were measured (P = 0.63). However, mice immunized with RF rPcAMA1 did produce high titers of antibodies that preferentially recognized the RF antigen over the RA antigen (P < 0.001). The converse was true for mice immunized with RA rPcAMA1 (P < 0.001). For PcMSP142, immunization with RF rPcMSP142 induced a threefold higher titer of antibodies than immunization with RA rPcMSP142 when the responses against the immunizing antigen were measured (P = 0.005). As expected, mice immunized with RF rPcMSP142 had high titers of antibodies that preferentially recognized the RF antigen over the RA antigen (P < 0.001). Again, the converse was true for mice immunized with RA rPcMSP142 (P = 0.02).

FIG. 4.

Titers of antigen (Ag)-specific IgG antibodies that recognize disulfide-dependent epitopes of rPcAMA1 or rPcMSP142. In trial 4, the titers of antibodies present in sera collected 2 weeks following the third immunization with RF or RA rPcAMA1 (A) or with RF or RA rPcMSP142 (B) formulated with Quil A as the adjuvant were determined by ELISA. The wells were coated with RF rPcAMA1 (□), RA rPcAMA1 (▒), RF rPcMSP142 (▪), or RA rPcMSP142 (▧). The titer was calculated as the reciprocal of the dilution of serum that yielded an A405 of 0.5. The mean IgG titers (103) ± standard deviation are shown for each group of rPcAMA1- and rPcMSP142-immunized mice.

The isotypic profiles and avidities of the antibodies present in prechallenge sera in trial 4 were also measured by ELISA (Table 1). Isotyping assays with RF rPcAMA1-coated wells showed a dominant IgG1 response in mice immunized with either RF rPcAMA1 or RA rPcAMA1 (P < 0.001) compared to the responses achieved with each of the other IgG isotypes. Assays with RF rPcMSP142-coated plates also revealed a dominant IgG1 response in mice immunized with RF rPcMSP142 (P < 0.001). Mice immunized with RA rPcMSP142 produced similar quantities of IgG1 and IgG2a/c. The antigen-specific IgM levels in mice immunized with PcAMA1 or PcMSP142 were not significantly different from those observed in adjuvant-treated control mice (data not shown). For both PcAMA1 and PcMSP142, the avidities of antibodies induced by immunization with the RF and RA antigens were comparable when binding was assayed with plates coated with RF PcAMA1 or RF PcMSP142 (P > 0.3).

TABLE 1.

Isotype profiles and avidity indices for prechallenge sera in trial 4a

| Immunization group | IgG concn (U/ml [102])

|

Avidity index | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG1 | IgG2a/c | IgG2b | IgG3 | ||

| RF PcAMA1 | 791 ± 216 | 26 ± 20 | 23 ± 16 | 0.2 ± 0.04 | 1.53 ± 0.09 |

| RA PcAMA1 | 221 ± 56 | 8 ± 6 | 12 ± 10 | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 1.33 ± 0.40 |

| RF PcMSP142 | 1,831 ± 629 | 153 ± 54 | 93 ± 33 | 1 ± 0.4 | 1.61 ± 0.16 |

| RA PcMSP142 | 159 ± 112 | 53 ± 23 | 43 ± 20 | 15 ± 19 | 1.41 ± 1.32 |

Isotype profiles and avidity indices were determined by ELISA with plates coated with RF PcAMA1 or RF PcMSP142.

The data on the immunization-induced PcAMA1- and PcMSP142-specific antibody responses were tested to determine if they correlated with protection against P. chabaudi malaria. For this analysis, mice immunized with the RF and RA versions of each antigen were considered to be a single group, and correlations were evaluated by using paired antibody and parasitemia data from individual animals. As shown in Table 2, the titer of prechallenge antibodies that specifically recognized RF PcAMA1 or PcMSP142 was inversely correlated with the peak level of P. chabaudi parasitemia, indicative of a protective role for these antibodies. In light of these data and considering the dominance of the IgG1 response, it was not surprising to see a similar inverse correlation between IgG1 levels and parasitemia levels. Conversely, increasing titers of prechallenge antibodies that bound to linear epitopes associated with RA PcAMA1 or RA PcMSP142 were detrimental, as they directly correlated with increasing levels of P. chabaudi parasitemia. No significant correlation between the level of IgG2a/c, IgG2b, or IgG3 antibodies specific for PcAMA1 or PcMSP142 and the level of parasitemia was apparent. The avidities of the PcAMA1 and PcMSP142 antibodies were not a distinguishing feature of the vaccine-induced response relative to protection.

TABLE 2.

Correlation of prechallenge antibodies that specifically recognized PcAMA1 or PcMSP142 with peak P. chabaudi parasitemia

| Antibody response | Statistical data for peak level of parasitemia

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PcAMA1a

|

PcMSP142b

|

|||

| r value | P value | r value | P value | |

| RF antigen titer | −0.90 | <0.001 | −0.66 | 0.04 |

| RA antigen titer | 0.81 | 0.004 | 0.79 | 0.007 |

| IgG1 | −0.93 | <0.001 | −0.67 | 0.03 |

| IgG2a/c | −0.36 | 0.31 | −0.60 | 0.064 |

| IgG2b | −0.45 | 0.19 | −0.58 | 0.082 |

| IgG3 | 0.08 | 0.83 | 0.40 | 0.25 |

| Avidity | −0.34 | 0.34 | −0.42 | 0.22 |

Pearson product-movement correlation determined on log10-transformed data points.

Pearson product-movement correlation determined on linear data points.

Use of identified correlates of antibody-mediated immunity to predict PcAMA1 and PcMSP142 vaccine efficacies.

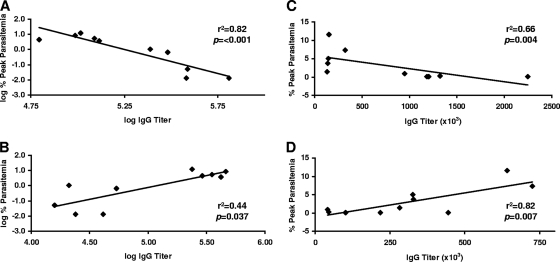

Figure 5 shows the results of a linear regression analysis comparing prechallenge antibody titers to RF and RA PcAMA1 (Fig. 5A and B) and to RF and RA PcMSP142 (Fig. 5C and D) individually with the outcome of P. chabaudi infection in trial 4. On the basis of these data, a multiple-regression analysis was utilized to generate equations that could be used to predict the peak level of P. chabaudi parasitemia on the basis of the prechallenge antibody titers against the RF antigen and the RA antigen considered in combination. To point out the relationship between these immune parameters and the expected impact on the outcome of infection, vaccine efficacy was predicted on the basis of a range of theoretical prechallenge antibody titers to both RF antigen and RA antigen (Table 3). For the rPcAMA1 formulation, a prechallenge antibody titer of 100,000 against RF rPcAMA1 and an associated titer of only 10,000 against RA rPcAMA1 were predicted to reduce the peak level of P. chabaudi parasitemia by approximately fourfold. A reduction in the peak level of parasitemia was expected to increase substantially to ∼25-fold, if these prechallenge antibody titers to RF and RA rPcAMA1 were proportionally doubled to 200,000 and 20,000, respectively. If a titer of 200,000 against RF rPcAMA1 was maintained, further increases in the level of antibodies that recognize linear epitopes of RA rPcAMA1 would only marginally influence protective efficacy. The situation with the rPcMSP142 formulation was somewhat different. A prechallenge titer of 100,000 against RF rPcMSP142 with a corresponding titer of 10,000 against RA rPcMSP142 was predicted to markedly reduce the peak level of P. chabaudi parasitemia by 9- to 10-fold. However, only a limited improvement would be anticipated by a doubling of these prechallenge titers. As important, further increases in the titer of prechallenge antibodies that recognize only RA rPcMSP142 would be expected to negatively affect vaccine efficacy even when high levels of antibodies that recognize RF rPcMSP142 are maintained.

FIG. 5.

Correlation between vaccine-induced PcAMA1 and PcMSP142 antibody responses and the outcome of P. chabaudi infection. The log IgG titers of vaccine-induced antibodies specific for RF PcAMA1 (A) or RA PcAMA1 (B) were compared with the log percent peak level of P. chabaudi parasitemia by linear regression analysis. For the PcMSP142 vaccines, nontransformed prechallenge IgG titers specific for RF PcMSP142 (C) or RA PcMSP142 (D) were compared with the peak level of P. chabaudi parasitemia by linear regression analysis. Each panel shows the r2 and P values, which indicate the strength and the significance of the relationships, respectively. Antibody and parasitemia data are based on the results of trial 4.

TABLE 3.

Relationship between prechallenge antibody titers and the expected impact on the outcome of infection

| Vaccine antigen | Titer

|

Predicted peak parasitemia (%) | Fold reduction in level of parasitemiac | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | RA | |||

| PcAMA1 RFa | 100,000 | 10,000 | 3.31 | 4.0 |

| 200,000 | 20,000 | 0.49 | 26.9 | |

| 200,000 | 100,000 | 0.63 | 20.8 | |

| 200,000 | 200,000 | 0.71 | 18.6 | |

| 200,000 | 400,000 | 0.79 | 16.6 | |

| PcMSP142 RFb | 100,000 | 10,000 | 1.41 | 9.3 |

| 200,000 | 20,000 | 1.27 | 10.3 | |

| 200,000 | 100,000 | 2.12 | 6.2 | |

| 200,000 | 200,000 | 3.19 | 4.1 | |

| 200,000 | 400,000 | 5.31 | 2.5 | |

For PcAMA1, log(parasitemia) = 14.48 − [2.92(log titer for RF form)] + [0.16(log titer for RA form)].

For PcMSP142, parasitemia = 1.54 − [2.42 × 10−6(titer of RF form)] + [1.06 × 10−5(titer of RA form)].

On the basis of a peak level of parasitemia of 13.13% in adjuvant-treated control mice (trial 4).

To independently evaluate the ability of these in vitro correlates to predict vaccine efficacy, an additional immunization and challenge trial was completed. In trial 5, groups of mice were immunized three times with 25 μg of RF rPcAMA1 or RF rPcMSP142 formulated with Quil A as the adjuvant or with adjuvant alone. Two weeks following the final immunization, prechallenge sera were obtained for analysis of the antibody responses and the mice were then challenged with P. chabaudi-parasitized RBCs.

Table 4 shows the prechallenge antigen-specific titers against RF and RA PcAMA1 and PcMSP142 along with the predicted and observed peak levels of parasitemia for each animal. Parasitemia was predicted by using the equations established in trial 4 relating the prechallenge vaccine-induced antibody titers to the peak level of parasitemia. The mean peak level of parasitemia in Quil A-treated control mice was 8.93% ± 4.83% (n = 10). High titers of PcAMA1-specific antibodies were induced and were predicted to be sufficient to nearly completely suppress P. chabaudi blood-stage parasite growth. This was confirmed upon challenge infection. Blood-stage P. chabaudi infected RBCs were not detected in 7 of 10 PcAMA1-immunized animals. Minimal parasitemia was observed in the remaining three mice in the PcAMA1-vaccinated group (∼0.02%). Given the remarkably low levels of the predicted and the observed P. chabaudi peak parasitemia, a reliable correlation coefficient could not be calculated.

TABLE 4.

Prechallenge antigen-specific titers against RF and RA PcAMA1 and PcMSP142 and predicted and observed peak levels of parasitemia

| Vaccine and animal no. | Antigen titer (103)

|

Level of parasitemia (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | RA | Predicteda | Observed | |

| PcAMA1a | ||||

| 1 | 705 | 49 | 0.015 | 0.02 |

| 2 | 809 | 337 | 0.014 | <0.01 |

| 3 | 840 | 70 | 0.010 | <0.01 |

| 4 | 853 | 212 | 0.011 | 0.02 |

| 5 | 871 | 85 | 0.009 | 0.02 |

| 6 | 918 | 119 | 0.008 | <0.01 |

| 7 | 945 | 86 | 0.007 | <0.01 |

| 8 | 967 | 283 | 0.008 | <0.01 |

| 9 | 1,118 | 130 | 0.005 | <0.01 |

| 10 | 1,634 | 206 | 0.002 | <0.01 |

| Mean | 966 | 158 | 0.009 | <0.01 |

| SD | 258 | 97 | 0.004 | |

| PcMSP142b | ||||

| 1 | 767 | 91 | 0.661 | 1.59 |

| 2 | 790 | 104 | 0.739 | 0.52 |

| 3 | 797 | 208 | 1.826 | 1.87 |

| 4 | 830 | 56 | 0.138 | 0.14 |

| 5 | 877 | 185 | 1.392 | 2.10 |

| 6 | 1,165 | 77 | 0.000 | 0.02 |

| 7 | 1,277 | 126 | 0.000 | 4.78 |

| 8 | 1,301 | 41 | 0.000 | 0.40 |

| 9 | 1,506 | 109 | 0.000 | 2.49 |

| 10 | 1,512 | 70 | 0.000 | 0.30 |

| Mean | 1,082 | 107 | 0.476 | 1.42 |

| SD | 303 | 54 | 0.668 | 1.48 |

For PcAMA1, log(parasitemia) = 14.48 − [2.92(log titer for RF form)] + [0.16(log titer for RA form)].

For PcMSP142, parasitemia = 1.54 − [2.42 × 10−6(titer for RF form)] + [1.06 × 10−5(titer for RA form)].

As expected, the group of PcMSP142-immunized mice was also solidly protected against P. chabaudi malaria (Table 4) and had a mean peak level of parasitemia of only 1.42% ± 1.48%, which was ∼6-fold lower than that for the adjuvant-treated controls (P < 0.01). However, the initial analysis indicated that the parasitemia levels predicted on the basis of the prechallenge antibody responses to RF and RA PcMSP142 did not correlate well with the parasitemia levels observed following P. chabaudi challenge infection (r = 0.12, P = 0.75). As shown in Table 4, the lack of a correlation was a particular problem for the four animals (7 to 10) with the highest prechallenge antibody titers to RF PcMSP142. Analysis of the data for 6 of 10 animals with RF PcMSP142-specific antibody titers below 1.2 × 106 revealed a strong correlation between the predicted and the observed levels of parasitemia (r = 0.87, P = 0.02).

DISCUSSION

The development of AMA1- and MSP1-based vaccines for P. falciparum has faced considerable challenges related to the production of recombinant antigens in the proper conformation, adjuvant selection, and the polymorphism of protective epitopes. Progress has been made in overcoming a number of these issues (18, 28). However, the clinical trial data needed to further guide these efforts are difficult to obtain quickly due to the need for testing in complex field trials in areas where malaria is endemic (15, 30, 31, 35, 42, 47, 49, 56). Confounding this situation is the current lack of an adequate body of data that defines measurable vaccine-induced AMA1- and MSP1-specific immune responses that are associated with protection in vivo. Recent studies involving Aotus monkeys immunized with P. falciparum MSP142 and challenged with P. falciparum noted some association between prechallenge antibody responses measured by ELISA and/or GIA and protection, generally for responses beyond a given threshold (27, 45). Further refinement of this type of analysis of protective and nonprotective antibody responses is needed to improve the ability to predict vaccine efficacy on the basis of diverse immunization-induced responses.

Studies of malaria parasites in rodents afford flexibility for the testing of the immunogenicities and the efficacies of blood-stage malaria vaccine formulations and the evaluation of in vitro immunoassays that might predict the outcome of infection. In the present study with a P. chabaudi model, the immunogenicities and efficacies of the rPcAMA1 and rPcMSP142 vaccine formulations tested were variable and consistent with those described in our previous reports (4, 5). As such, our expectation was that an in-depth analysis of the prechallenge antibody responses would allow us to identify immune correlates of protection. In our initial studies, we generally observed a marked boost in the antigen-specific antibody responses following a second immunization, regardless of the specific antigen, dose, or adjuvant used. We noted only marginal increases in antibody titers with a third immunization. These data suggest that more than three immunizations would not be expected to effectively boost the PcAMA1 or PcMSP142 antibody responses further nor result in an increase in protection upon challenge. Consideration of the efficacy data shows that the use of alum as the adjuvant was partially effective for the PcMSP142 vaccine but was unacceptable for use with the PcAMA1 vaccine. This may relate to the particulate nature and/or the strong Th2-biasing effects of alum. Alternatively, Quil A was suitable for use with both the PcAMA1 and the PcMSP142 vaccines, although the Quil A-based formulations of PcMSP142 required a higher dose of antigen (25 μg per immunization) to be effective.

In our initial analysis of antibody responses in animals immunized with various doses of PcAMA1 or PcMSP142 formulated in different adjuvants, we could not establish correlations between a reduction in the level of P. chabaudi parasitemia and the prechallenge antibody titer, isotype, avidity, or epitope specificity. The antigen-specific antibodies induced by three sequential immunizations in each of the first three trials were less variable than we anticipated, as they were primarily IgG1 and had comparable titers and avidities. Attempts to establish correlates of protection when dissimilar antigen-adjuvant formulations are compared may also be problematic. The antibodies elicited by each formulation may mediate protection by multiple, distinct mechanisms. Beyond B cells and antibodies, adjuvant-dependent influences on the balance of protective and nonprotective T-cell responses induced by immunization may have further masked our ability to establish correlations.

In our fourth trial, we evaluated the response and protective efficacy induced by immunization with the RF antigen compared with those induced by immunization with the RA antigen. By using the same antigen dose and adjuvant, we also reduced the effects of some of the confounding variables mentioned above. Again, we could not establish any relationship between antibody isotype or avidity and protection. We were, however, able to show that the titer of antibody against the RF antigen negatively correlated with the level of parasitemia and that the titer of antibody against the RA antigen positively correlated with the level of parasitemia. Somewhat unexpectedly, the relative importance of these two measures of vaccine-induced responses as predictors of protection differed for the PcAMA1 and the PcMSP142 vaccines. Consideration of these differences in clinical trials evaluating P. falciparum AMA1- and MSP1-based vaccines may be beneficial.

In vitro GIA data with antibodies that recognize P. falciparum AMA1 have indicated the importance of conformational B-cell epitopes as targets of neutralizing antibodies (9, 10, 23). Early reports also showed that proper disulfide bonds of the ectodomain of PcAMA1 are required for protection against lethal P. chabaudi challenge (2, 12). Through in vivo studies involving the immunization of B-cell-deficient JHD mice, we previously showed that PcAMA1 vaccine-induced protection against nonlethal P. chabaudi malaria was largely, if not completely, antibody mediated (4). In the current study, we observed an ∼50% reduction in the level of P. chabaudi parasitemia in mice immunized with RA rPcAMA1. We interpret these data in combination to indicate that antibodies against linear epitopes of PcAMA1 are partially effective against nonlethal P. chabaudi malaria but that the most effective protective response involves disulfide-dependent B-cell epitopes. This is reflected in the marked gain in efficacy that we predicted when the prechallenge titers of antibodies against RF PcAMA1 were simply doubled. If high titers of antibodies against conformational epitopes of RF PcAMA1 are induced, the presence of an additional population of antibodies specific for linear determinants of RA PcAMA1 is not predicted to greatly influence efficacy against homologous challenge.

Protective epitopes associated with the disulfide-bonded epidermal growth factor-like domains of MSP142 have largely been defined by using antibodies that passively protect mice in vivo (6, 29, 46) or that inhibit the growth of P. falciparum in vitro (8, 37, 52). In the present study, we observed a partial reduction in the rate of P. chabaudi malaria following immunization with RA PcMSP142. This may reflect some protective role for antibodies that recognize linear determinants of MSP1, as has been suggested on the basis of GIA data for epitopes associated with MSP133 (57). However, we believe that this partial protection more likely reflects the contribution of antibody-independent, cell-mediated immune responses to PcMSP142 that we previously demonstrated in immunization and challenge studies with rPcMSP142-based vaccines and B-cell-deficient mice (4). Of particular interest and unlike the results that we observed for PcAMA1, our data further indicate that antibodies against nonconformational epitopes of MSP1 negatively affect protection even in the presence of high titers of otherwise protective antibodies. Some of these antibodies may be related to the MSP1-specific, blocking antibodies that have previously been demonstrated to be functional in vitro in P. falciparum growth inhibition assays (20, 52).

In our final trial (trial 5), we were able to confirm our findings and show that the titers of prechallenge antibodies against the RA and RF antigens induced by prior immunization with PcAMA1 and PcMSP142 could be used to predict vaccine efficacy. It is of interest that sufficiently high titers of antibodies to RF PcAMA1 are predicted to and in fact do completely neutralize P. chabaudi parasites, such that detectable parasitemia is not observed. We have noted such potent protection with PcAMA1-based vaccines in our earlier studies (4, 5). This is generally not the case for PcMSP142. While immunization with PcMSP142 induces solid protection against challenge infection, most animals do develop some low level of parasitemia. In MSP1 vaccine studies with actively or passively immunized mice, this has been attributed to the need to mount an immune response to other blood-stage antigens before parasitemia can be fully suppressed (13, 22). In trial 5, blood-stage parasites were detected in all PcMSP142-immunized mice, and we noted a reasonable correlation between the predicted and the observed peak levels of parasitemia, with one caveat. The correlation dropped off in the PcMSP142-immunized animals that mounted the strongest responses upon immunization and that developed the highest antibody titers. These data again suggest that MSP142-specific antibodies alone cannot completely protect against blood-stage malaria. Furthermore, efforts to induce antibodies beyond a certain level will not improve efficacy and may in fact be counterproductive. Such a strong, dominant, and ongoing immune response to a single antigen may delay the development of responses to other parasite antigens required to ultimately clear the infection. Further investigation will be necessary to confirm this possibility.

The studies with a rodent malaria model described here gave us an opportunity to complete in vivo studies of the correlates of vaccine-induced immunity that would not be feasible with human subjects for ethical reasons. Establishing the relevance of our findings for P. falciparum AMA1 and MSP1 vaccines will require additional work. As clinical testing with human subjects proceeds, however, we feel that several pieces of information are relevant and should be considered. First, the results again confirm that AMA1- and MSP142-based vaccines need to induce high titers of antibodies to maximally suppress blood-stage parasitemia. This has been a critical issue in trials of P. falciparum AMA1 and MSP142 with monkeys (7, 11, 14, 25, 27, 45, 48) and humans (15, 30, 31, 35, 42, 47, 49, 56), most notably for formulations that do not utilize complete Freund's adjuvant. This will be an even greater challenge with every additional P. falciparum MSP142 and/or AMA1 allele that must be added to a vaccine cocktail to counter issues of polymorphisms. The question of whether or not this can be achieved should continue to be discussed. Second, in P. falciparum AMA1 and MSP142 vaccine trials, it will be informative to measure the titers against the RF and RA antigens in an effort to establish associations with protection. In doing so, these values should also be considered in combination when an attempt to predict efficacy is made. The data can be obtained from simple ELISA-based assays. This approach is distinct from the current practice of measuring the titers of antibodies to conformational epitopes of selected subdomains of the immunizing antigen. Third, immunization with P. falciparum MSP142 can clearly induce protective antibodies but will also likely induce some level of blocking antibodies that are predicted to reduce efficacy. Work will need to continue to determine if immunization with monomeric or dimeric MSP142 (44) or with MSP142 complexed with MSP183, MSP-6, MSP-7, and/or MSP-9 (24, 26, 32, 34, 40, 51) more effectively induces merozoite-neutralizing antibodies. Finally, focusing on the induction of a sufficiently strong and sustained B-cell response to a single antigen in order to control blood-stage malaria is unwise. We need to better understand if other responses, including cell-mediated responses, elicited by infection are synergistic or antagonistic to vaccine-induced responses (16, 19, 38, 39, 41, 53-55). In addition, the targets of these protective responses will need to be identified.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH-NIAID grants AI49585 and AI12710.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso, P. L., J. Sacarlal, J. J. Aponte, A. Leach, E. Macete, P. Aide, B. Sigauque, J. Milman, I. Mandomando, Q. Bassat, C. Guinovart, M. Espasa, S. Corachan, M. Lievens, M. M. Navia, M. C. Dubois, C. Menendez, F. Dubovsky, J. Cohen, R. Thompson, and W. R. Ballou. 2005. Duration of protection with RTS,S/AS02A malaria vaccine in prevention of Plasmodium falciparum disease in Mozambican children: single-blinded extended follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Lancet 3662012-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anders, R. A., P. E. Crewther, S. Edwards, M. Margetts, M. L. S. M. Matthew, B. Pollock, and D. Pye. 1997. Immunization with recombinant AMA1 protects mice against infection with Plasmodium chabaudi. Vaccine 16240-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aponte, J. J., P. Aide, M. Renom, I. Mandomando, Q. Bassat, J. Sacarlal, M. N. Manaca, S. Lafuente, A. Barbosa, A. Leach, M. Lievens, J. Vekemans, B. Sigauque, M. C. Dubois, M. A. Demoitié, M. Sillman, B. Savarese, J. G. McNeil, E. Macete, W. R. Ballou, J. Cohen, and P. L. Alonso. 2007. Safety of the RTS,S/AS02D candidate malaria vaccine in infants living in a highly endemic area of Mozambique: a double blind randomized controlled phase I/IIb trial. Lancet 3701543-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns, J. M., Jr., P. R. Flaherty, P. Nanavati, and W. P. Weidanz. 2004. Protection against Plasmodium chabaudi malaria induced by immunization with apical membrane antigen-1 and merozoite surface protein-1 in the absence of gamma interferon or interleukin-4. Infect. Immun. 725605-5612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns, J. M., Jr., P. R. Flaherty, M. M. Romero, and W. P. Weidanz. 2003. Immunization against Plasmodium chabaudi malaria using combined formulations of apical membrane antigen-1 and merozoite surface protein-1. Vaccine 211843-1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns, J. M., Jr., W. R. Majarian, J. F. Young, T. M. Daly, and C. A. Long. 1989. A protective monoclonal antibody recognizes an epitope in the C-terminal cysteine-rich domain in the precursor of the major merozoite surface antigen of the rodent malarial parasite Plasmodium yoelii. J. Immunol. 1432670-2676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, S. P., S. E. Case, W. L. Gosnell, A. Hashimoto, K. J. Kramer, L. Q. Tam, C. Q. Hashiro, C. M. Nikaido, H. L. Gibson, C. T. Lee-Ng, P. J. Barr, B. T. Yokota, and G. S. N. Hui. 1996. A recombinant baculovirus 42-kilodalton C-terminal fragment of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 protects Aotus monkeys against malaria. Infect. Immun. 64253-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chappel, J. A., and A. A. Holder. 1993. Monoclonal antibodies that inhibit Plasmodium falciparum invasion in vitro recognize the first growth factor-like domain of merozoite surface protein-1. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 60303-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coley, A. M., K. Parisi, R. Masciantonio, J. Hoeck, J. L. Casey, V. J. Murphy, K. S. Harris, A. H. Batchelor, R. F. Anders, and M. Foley. 2006. The most polymorphic residue on Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen 1 determines binding of an invasion-inhibitory antibody. Infect. Immun. 742628-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins, C. R., C. Withers-Martinez, G. A. Bentley, A. H. Batchelor, A. W. Thomas, and M. J. Blackman. 2007. Fine mapping of an epitope recognized by an invasion-inhibitory monoclonal antibody on the malaria vaccine candidate apical membrane antigen 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2827431-7441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins, W. E., D. Pye, P. E. Crewther, K. L. Vandenberg, G. G. Galland, A. J. Sulzer, D. J. Kemp, S. J. Edwards, R. L. Coppel, J. S. Sullivan, C. L. Morris, and R. F. Anders. 1994. Protective immunity induced in squirrel monkeys with recombinant apical membrane antigen-1 of Plasmodium fragile. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 51711-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crewther, P. E., M. L. S. M. Matthew, R. H. Flegg, and R. F. Anders. 1996. Protective immune responses to apical membrane antigen 1 of Plasmodium chabaudi involve recognition of strain-specific epitopes. Infect. Immun. 643310-3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daly, T. M., and C. A. Long. 1995. Humoral response to a carboxyl-terminal region of the merozoite surface protein-1 plays a predominant role in controlling blood-stage infection in rodent malaria. J. Immunol. 155236-243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darko, C. A., E. Angov, W. E. Collins, E. S. Bergmann-Leitner, A. S. Girouard, S. L. Hitt, J. S. McBride, C. L. Diggs, A. A. Holder, C. A. Long, J. W. Barnwell, and J. A. Lyon. 2005. The clinical grade 42 kilodalton fragment of merozoite surface protein 1 of Plasmodium falciparum strain FVO expressed in Escherichia coli protects Aotus nancymai against challenge with homologous erythrocytic stage parasites. Infect. Immun. 73287-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dicko, A., D. J. Diemert, I. Sagara, M. Sogoba, M. B. Niambele, M. H. Assadou, O. Guindo, B. Kamate, M. Baby, M. Sissoko, E. M. Malkin, M. P. Fay, M. A. Thera, K. Miura, A. Dolo, D. A. Diallo, G. E. Mullen, C. A. Long, A. Saul, O. Doumbo, and L. H. Miller. 2007. Impact of a Plasmodium falciparum AMA1 vaccine on antibody responses in adult Malians. PLoS One 10e1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dodoo, D., F. M. Omer, J. Todd, B. D. Akanmori, K. A. Korman, and E. M. Riley. 2001. Absolute levels and ratios of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine production in vitro predict clinical immunity to Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 185971-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galinsky, M. R., A. R. Dluzewski, and J. W. Barnwell. 2005. A mechanistic approach to merozoite invasion of red blood cells: merozoite biogenesis, rupture, and invasion of erythrocytes, p. 113-168. In I. W. Sherman (ed.), Molecular approaches to malaria. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 18.Genton, B., and Z. H. Reed. 2007. Asexual blood-stage malaria vaccine development: facing the challenges. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 20467-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grun, J. L., and W. P. Weidanz. 1981. Immunity to Plasmodium chabaudi adami in the B cell deficient mouse. Nature 290143-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guevera Patiño, J. A., A. A. Holder, J. S. McBride, and M. J. Blackman. 1997. Antibodies that inhibit merozoite surface protein-1 processing and erythrocyte invasion are blocked by naturally acquired human antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 1861689-1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hay, S. I., C. A. Guerra, A. J. Tatem, A. M. Noor, and R. W. Snow. 2004. The global distribution and population at risk of malaria: past, present, and future. Lancet Infect. Dis. 4327-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirunpetcharat, C., P. Vukovic, X. Q. Liu, D. C. Kaslow, L. H. Miller, and M. F. Good. 1999. Absolute requirement for an active immune response involving B cells and Th cells in immunity to Plasmodium yoelii passively acquired with antibodies to the 19-kDa carboxyl-terminal fragment of merozoite surface protein-1. J. Immunol. 1627309-7314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodder, A. N., P. E. Crewther, and R. F. Anders. 2002. Specificity of the protective antibody response to apical membrane antigen-1. Infect. Immun. 693286-3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holder, A. A., and R. R. Freeman. 1984. The three major antigens on the surface of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites are derived from a single high molecular weight precursor. J. Exp. Med. 160624-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar, S., A. Yadava, D. B. Keister, J. H. Tian, M. Ohl, K. A. Perdue-Greenfield, L. H. Miller, and D. C. Kaslow. 1995. Immunogenicity and in vivo efficacy of recombinant Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 in Aotus monkeys. Mol. Med. 1325-332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, X., H. Chen, T. H. Oo, T. M. Daly, L. W. Bergman, S. C. Liu, A. H. Chishti, and S. S. Oh. 2004. A co-ligand complex anchors Plasmodium falciparum merozoites to the erythrocyte invasion receptor band 3. J. Biol. Chem. 2795765-5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lyon, J. A., E. Angov, M. P. Fay, J. S. Sullivan, A. S. Girourd, S. J. Robinson, E. S. Bergmann-Leitner, E. H. Duncan, C. A. Darko, W. E. Collins, C. A. Long, and J. W. Barnwell. 2008. Protection induced by Plasmodium falciparum MSP142 is strain-specific, antigen and adjuvant dependent, and correlates with antibody responses. PLoS One 3e2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahanty, S., A. Saul, and L. H. Miller. 2003. Progress in the development of recombinant and synthetic blood-stage malaria vaccines. J. Exp. Biol. 2063781-3788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majarian, W. M., T. M. Daly, W. P. Weidanz, and C. A. Long. 1984. Passive immunization against murine malaria with an IgG3 monoclonal antibody. J. Immunol. 1323131-3137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malkin, E., C. A. Long, A. W. Stowers, L. Zou, S. Singh, N. J. MacDonald, D. L. Narum, A. P. Miles, A. C. Orcutt, O. Muratova, S. E. Moretz, H. Zhou, A. Diouf, M. Fay, E. Tierney, P. Leese, S. Mahanty, L. H. Miller, A. Saul, and L. B. Martin. 2007. Phase 1 study of two merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP142) vaccines for Plasmodium falciparum malaria. PLoS Clin. Trials 2e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malkin, E. M., D. J. Diemert, J. H. McArthur, J. R. Perreault, A. P. Miles, B. K. Giersing, G. E. Mullen, A. Orcutt, O. Muratova, M. Awkal, H. Zhou, J. Wang, A. Stowers, C. A. Long, S. Mahanty, L. H. Miller, A. Saul, and A. P. Durbin. 2005. Phase 1 clinical trial of apical membrane antigen 1: an asexual blood-stage vaccine for Plasmodium falciparum. Infect. Immun. 733677-3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McBride, J. S., and H. G. Heidrich. 1987. Fragments of the polymorphic Mr 185,000 glycoprotein from the surface of isolated Plasmodium falciparum merozoites form an antigenic complex. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2371-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McIntosh, R. S., J. Shi, R. M. Jennings, J. C. Chappel, T. F. de Koning-Ward, T. Smith, J. Green, M. van Egmond, J. H. Leusen, M. Lazarou, J. van de Winkel, T. S. Jones, B. S. Crabb, A. A. Holder, and R. J. Pleass. 2007. The importance of human FcγRI in mediating protection to malaria. PLoS Pathog. 3e72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mello, K., T. M. Daly, J. Morrissey, A. B. Vaidya, C. A. Long, and L. W. Bergman. 2002. A multigene family that interacts with the amino terminus of Plasmodium MSP-1 identified using the yeast two-hybrid system. Eukaryot. Cell 1915-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ockenhouse, C. F., E. Angov, K. E. Kester, C. Diggs, L. Soisson, J. F. Cummings, V. A. Stewart, D. R. Palmer, B. Mahajan, U. Krzych, N. Tornieporth, M. Delchambre, M. Vanhandenhove, O. Ofori-Anyinam, J. Cohen, J. A. Lyon, D. G. Heppner, and the MSP-1 Working Group. 2006. Phase I safety and immunogenicity trial of FMP1/AS02A, a Plasmodium falciparum MSP-1 asexual blood stage vaccine. Vaccine 243009-3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Donnell, R. A., A. Saul, A. F. Cowman, and B. S. Crabb. 2000. Functional conservation of the malaria vaccine antigen MSP-119 across distantly related Plasmodium species. Nat. Med. 691-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Donnell, R. A., T. F. de Koning-Ward, R. A. Burt, M. Bockarie, J. C. Reeder, A. F. Cowman, and B. S. Crabb. 2001. Antibodies against merozoite surface protein (MSP)-119 are a major component of the invasion-inhibitory response in individuals immune to malaria. J. Exp. Med. 1931403-1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Omer, F. M., J. B. De Souza, and E. M. Riley. 2003. Differential induction of TGF-β regulates proinflammatory cytokine production and determines the outcome of lethal and non-lethal Plasmodium yoelii infections. J. Immunol. 1715430-5436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Othoro, C., A. A. Lal, B. Nahlen, D. Koech, A. S. Orago, and V. Udhayakumar. 1999. A low IL-10:TNF-α ratio is associated with malaria anemia in children residing in a holoendemic malaria region in Western Kenya. J. Infect. Dis. 179279-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pachebat, J. A., I. T. Ling, M. Grainger, C. Trucco, S. Howell, D. Fernandez-Reyes, R. Gunaratne, and A. A. Holder. 2001. The 22 kDa component of the protein complex on the surface of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites is derived from a larger precursor, merozoite surface protein 7. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 11783-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petritus, P. M., and J. M. Burns, Jr. 2008. Suppression of lethal Plasmodium yoelii malaria following protective immunization requires antibody-, IL-4-, and IFN-γ-dependent responses induced by vaccination and/or challenge infection. J. Immunol. 180444-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Polhemus, M. E., A. J. Magill, J. F. Cummings, K. E. Kester, C. F. Ockenhouse, D. E. Lanar, S. Dutta, A. Barbosa, L. Soisson, C. L. Diggs, S. A. Robinson, J. D. Haynes, V. A. Stewart, L. A. Ware, C. Brando, U. Krzych, R. A. Bowden, J. D. Cohen, M. C. Dubois, O. Ofori-Anyinam, E. De-Kock, W. R. Ballou, and D. G. Heppner, Jr. 2007. Phase I dose escalation safety and immunogenicity trial of Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen (AMA1) FMP2.1, adjuvanted with AS02A, in malaria-naïve adults at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. Vaccine 254203-4212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pullen, G. R., M. G. Fitzgerald, and C. S. Hosking. 1986. Antibody avidity determination by ELISA using thiocyanate elution. J. Immunol. Methods 8383-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanders, P. R., G. T. Cantin, D. C. Greenbaum, P. R. Gilson, T. Nebl, R. L. Moritz, J. R. Yates III, A. N. Hodder, and B. S. Crabb. 2007. Identification of protein complexes in detergent-resistant membranes of Plasmodium falciparum schizonts. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 154148-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh, S., K. Miura, H. Zhou, O. Muratova, B. Keegan, A. Miles, L. B. Martin, A. J. Saul, L. H. Miller, and C. A. Long. 2006. Immunity to recombinant Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP1): protection in Aotus nancymai monkeys strongly correlates with anti-MSP1 antibody titer and in vitro parasite-inhibitory activity. Infect. Immun. 744573-4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spencer Valero, L. M., S. A. Ogun, S. L. Fleck, I. T. Ling, T. J. Scott-Finnigan, M. J. Blackman, and A. A. Holder. 1998. Passive immunization with antibodies against three distinct epitopes on Plasmodium yoelii merozoite surface protein 1 suppresses parasitemia. Infect. Immun. 663925-3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stoute, J. A., J. Gombe, M. R. Withers, J. Siangla, D. McKinney, M. Onyango, J. F. Cummings, J. Milman, K. Tucker, L. Soisson, V. A. Stewart, J. A. Lyon, E. Angov, A. Leach, J. Cohen, K. E. Kester, C. F. Ockenhouse, C. A. Holland, C. L. Diggs, J. Wittes, D. G. Heppner, Jr., and the MSP-1 Malaria Vaccine Working Group. 2006. Phase 1 randomized double-blind safety and immunogenicity trial of Plasmodium falciparum malaria merozoite surface protein FMP1 vaccine, adjuvanted with AS02A, in adults in western Kenya. Vaccine 25176-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stowers, A. W., M. C. Kennedy, B. P. Keegan, A. Saul, C. A. Long, and L. H. Miller. 2002. Vaccination of monkeys with recombinant P. falciparum apical membrane antigen 1 confers protection against blood-stage malaria. Infect. Immun. 706961-6967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thera, M. A., O. K. Doumbo, D. Coulibaly, D. A. Diallo, I. Sagara, A. Dicko, D. J. Diemert, D. G. Heppner, Jr., V. A. Stewart, E. Angov, L. Soisson, A. Leach, K. Tucker, K. E. Lyke, C. V. Plowe, and the Mali FMP1 Working Group. 2006. Safety and allele-specific immunogenicity of a malaria vaccine in Malian adults: results of a phase I randomized trial. PLoS Clin. Trials 1e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Triglia, T., J. Healer, S. R. Caruana, A. N. Hodder, R. F. Anders, B. S. Crabb, and A. F. Cowman. 2000. Apical membrane antigen 1 plays a central role in erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium species. Mol. Microbiol. 38706-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trucco, C., D. Fernandez-Reyes, S. Howell, W. H. Stafford, T. J. Scott-Finnigan, M. Grainger, S. A. Ogun, W. R. Taylor, and A. A. Holder. 2001. The merozoite surface protein 6 gene codes for a 36 kDa protein associated with the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 complex. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 11291-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uthaipibull, C., B. Aufiero, S. E. H. Syed, B. Hansen, J. A. Guevara Patiño, E. Angov, I. T. Ling, K. Fegeding, W. D. Morgan, C. Ockenhouse, B. Birdsall, J. Feeney, J. A. Lyon, and A. A. Holder. 2001. Inhibitory and blocking monoclonal antibody epitopes on merozoite surface protein 1 of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J. Mol. Biol. 3071381-1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van der Heyde, H. C., D. Huszar, C. Woodhouse, D. D. Manning, and W. P. Weidanz. 1994. The resolution of acute malaria in a definitive model of B cell deficiency, the JHD mouse. J. Immunol. 1524557-4562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.von der Weid, T., N. Honarvar, and J. Langhorne. 1996. Gene-targeted mice lacking B cells are unable to eliminate a blood stage malaria infection. J. Immunol. 1562510-2516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walther, M., J. E. Tongren, L. Andrews, D. Korbel, E. King, H. Fletcher, R. F. Andersen, P. Bejon, F. Thompson, S. J. Dunachie, F. Edele, J. B. de Souza, R. E. Sinden, S. C. Gilbert, E. M. Riley, and A. V. Hill. 2005. Upregulation of TGF-beta, FOXP3, and CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells correlates with more rapid parasite growth in human malaria infection. Immunity 23287-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Withers, M. R., D. McKinney, B. R. Ogutu, J. N. Waitumbi, J. B. Milman, O. J. Apollo, O. G. Allen, K. Tucker, L. A. Soisson, C. Diggs, A. Leach, J. Wittes, F. Dubovsky, V. A. Stewart, S. A. Remich, J. Cohen, W. R. Ballou, C. A. Holland, J. A. Lyon, E. Angov, J. A. Stoute, S. K. Martin, D. G. Heppner, Jr., and the MSP-1 Malaria Vaccine Working Group. 2006. Safety and reactogenicity of an MSP-1 malaria vaccine candidate: a randomized phase Ib dose-escalation trial in Kenyan children. PLoS Clin. Trials 1e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yuen, D., W. H. Leung, R. Cheung, C. Hashimoto, S. F. Ng, W. Ho, and G. Hui. 2007. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of the N-terminal 33 kDa processed fragment of the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1, MSP1: implications for vaccine development. Vaccine 25490-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]