Abstract

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is an inherited disorder that is characterized by abnormal communication between the arteries and veins in the skin, mucosa, and various organs. HHT has been reported to show significant phenotypic variability and genetic heterogeneity with wide ethnic and geographic variations. Although mutations in the endoglin (ENG) and activin A receptor type II-like 1 (ACVRL1) genes have been known to cause HHT for more than 10 yr, little is known about the clinical features or genetic background of Korean patients with HHT. In addition, mutations in mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4 (SMAD4) are also seen in patients with the combined syndrome of juvenile polyposis and HHT. This study examined five Korean patients with the typical manifestations of HHT such as frequent epistaxis and pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. Direct sequencing of the ENG and ACVRL1 genes revealed one known mutation, ENG c.277C>T, in one patient and two novel mutations, ENG c.992-1G>C and ACVRL1 c.81dupT in two patients, respectively. The remaining two patients with negative results were screened for SMAD4 mutations as well as gross deletions of ENG and ACVRL1 using multiple ligation-dependent probe amplification, but none was detected. Despite the small number of patients investigated, we firstly report Korean patients with genetically confirmed HHT, and show the genetic and allelic heterogeneity underlying HHT.

Keywords: Telangiectasia, Hereditary Hemorrhagic; ENG; ACVRL1; SMAD4; Mutation; Korean

INTRODUCTION

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), which is also known as Rendu-Osler-Weber disease, is an autosomal dominantly inherited disorder that is characterized by abnormal communications between the arteries and veins (telangiectasia) in the skin, mucosa, and various organs (1). The prevalence of this disorder is estimated to be -1:1,300 to -1:40,000 with some geographical variations (2-9). The clinical features of HHT include spontaneous recurrent epistaxis, mucocutaneous telangiectases (particularly on the tongue, lips, oral cavity, fingers and nose), and arteriovenous malformations (AVM) in the pulmonary, cerebral, hepatic, gastrointestinal or spinal vessels (10).

HHT is genetically heterogeneous and can be subdivided into HHT-1 and HHT-2 according to mutations in the endoglin (ENG) gene and the activin A receptor type II-like 1 (ACVRL1) gene, respectively (11, 12). These two subtypes are clinically indistinguishable and share many phenotypes. However, there appears to be some differences in the frequency of some their clinical manifestations. Pulmonary AVMs are believed to be more common in patients with HHT-1 than in HHT-2 (7, 13-17). Families with HHT-2 generally tend to show a later onset of the symptoms and a milder phenotype. The vast majority (-80%) of the ENG mutations in HHT-1 patients lead to premature stop codons and truncated peptides, with no apparent hot focus. On the other hand, more than half (-53%) of the mutations identified in ACVRL1 are missense substitutions, and the majorities of those mutations are located in exons 8, 7, and 3. Some large deletions and insertions as well as some splice site mutations in these two genes have also been reported (2, 13, 18). Recently, other loci for HHT, HHT-3, and HHT-4, were identified by linkage analysis (19, 20). Moreover, there are diseases presenting overlapping features with HHT such as the Juvenile polyposis/hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia syndrome (JPHT) which is caused by the mutations in the mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4 (SMAD4) tumor suppressor gene (21).

HHT is considered to be more common than previously believed. However, there are no data on Korean patients with genetically confirmed HHT. Therefore, this study examined the clinical and genetic information of five Korean patients with the typical manifestations of HHT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

A clinical investigation and genetic analysis was performed in five Korean patients diagnosed with HHT according to the criteria suggested by Shovlin et al. (10). The frequency of epistaxis was graded according to the category suggested by Bergler et al. (22): grade 1, less than once per week; grade 2, a few times per week; grade 3, more than once per day.

DNA sequence analysis

After obtaining informed consent, the genomic DNA was isolated from the peripheral blood leukocytes using a Wizard Genomic DNA Purification kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.). DNA sequence analysis of the ENG, ACVRL1, and SMAD4 genes was carried out using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the primers designed by the authors. PCR was initially performed using a thermal cycler (model 9600, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.), and DNA sequencing was carried out using an ABI Prism 3100 Genetic Analyzer with a BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Applied Biosystems).

Multiple ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA)

To identify the deletional mutations, MLPA was performed following the directions provided by MRCHolland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands (http://www.mlpa.com), using a probe set for HHT (SALSA MLPA KIT P093 HHT/PPH1) covering 13 of the 14 exons of ENG (except for exon 12) and all the 10 exons of ACVRL. MLPA was performed on the ABI 9700 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). Amplicons were separated on a capillary sequencer (ABI 3130 genetic analyzer, Applied Biosystems). Before separation, Genescan-ROX 500 (Applied Biosystems) was added to the samples to facilitate estimation of fragment sizes. Data analysis was performed using the GeneScan (Applied Biosystems) and GeneMarker (SoftGenetics, State College, PA, U.S.A.) software. Relative peak area values obtained in the patients were compared to those obtained in healthy controls and were expressed as ratios. Signal ratios of approximately 0.5 were considered pathological.

RESULTS

Clinical findings

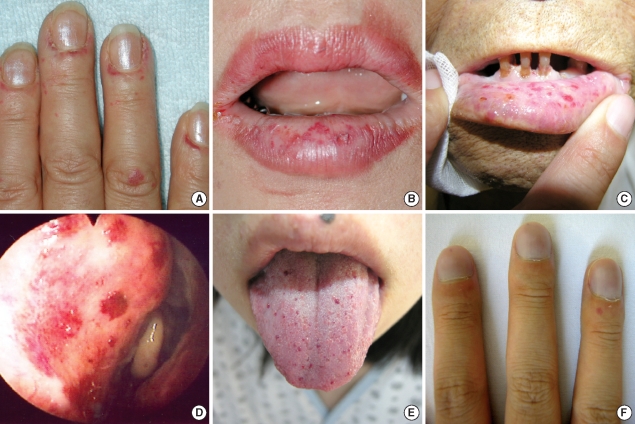

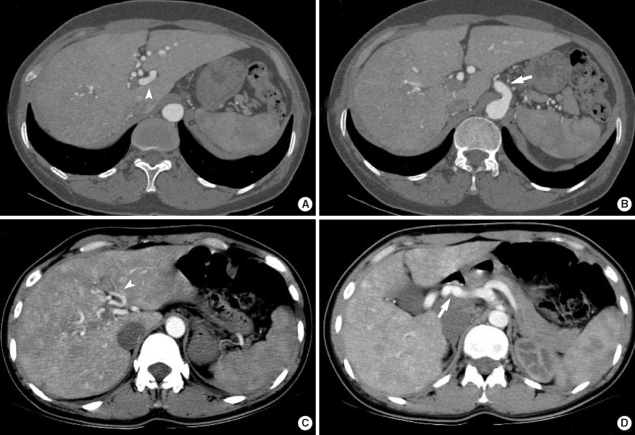

The Clinical features and mutations identified in the five Korean patients were summarized in the Table 1. Patient 1 had recurrent epistaxis and pulmonary AVM along with focal telangiectasia on the fingers (particularly the periungal regions), lips, and oral mucosa (Fig. 1A, B). A history of recurrent epistaxis was found in her father and 32-yr-old daughter (Fig. 2A). Computed tomography (CT) angiography of the liver showed an enlarged celiac axis and a prominent hepatic artery with multiple aberrant collateral vessels. Heterogeneous attenuation of the liver was also noted (Fig. 3A, B).

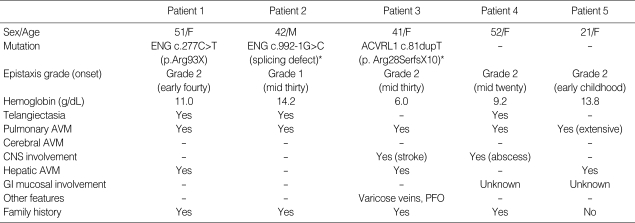

Table 1.

Clinical features and mutations identified in five Korean patients with HHT

*Novel mutations.

HHT, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia; AVM, arteriovenous malformation; CNS, central nervous system; GI, gastrointestinal; PFO, patent foramen ovale.

Fig. 1.

Clinical features of the HHT patients: (A) telangiectasia on the periungal regions of the fingers of patient 1, (B) telangiectasia on the lips of patient 1, (C) telangiectasia on the oral mucosa of the father of patient 2, (D) bleeding foci in the Kisselbach's plexus of patient 3; (E) microtelangia on the tongue of patient 5, and (F) clubbing fingers with one small hemangioma in patient 5.

Fig. 2.

Pedigrees of families of (A) patient 1 and (B) patient 2.

Fig. 3.

Radiology findings of the HHT patients. (A) and (B) CT angiography of the liver in patient 1 shows an enlarged celiac axis (arrow), a prominent hepatic artery (arrowhead) with multiple aberrant collateral vessels, and heterogeneous attenuation of the liver. (C) and (D) Abdominal CT of patient 3 shows severe tortuous dilatation of the hepatic artery (arrow) and its intrahepatic branches (arrowhead) with mottled hepatic enhancement.

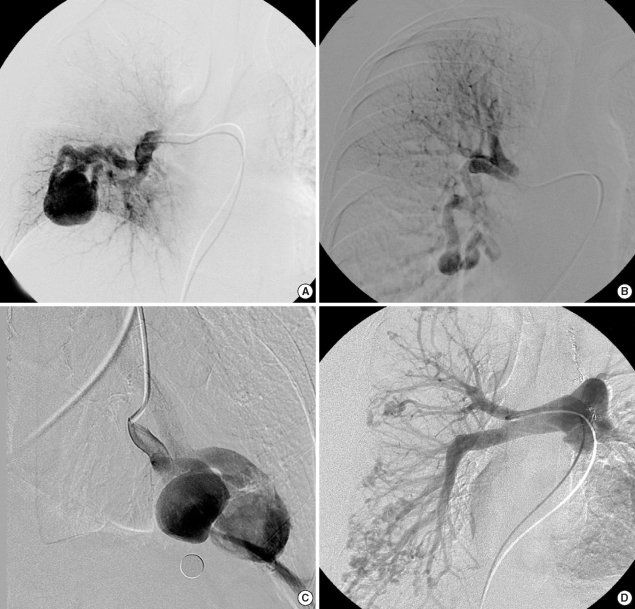

Patient 2 had pulmonary AVM and telelangiectasia was found on his tongue, along with a history of frequent epistaxis. Recurrent epistaxis histories were also found in his father, four sisters, and eight-year-old son. His father was diagnosed with HHT with recurrent massive epistaxis requiring frequent blood transfusions, telangiectasia on the oral mucosa (Fig. 1C), and pulmonary AVM. Pulmonary angiography of patient 2 revealed a large pulmonary AVM with an aneurysmal sac (Fig. 4A). Selective coil embolization of the feeder vessels of the pulmonary AVM was performed and the hemoptysis subsided.

Fig. 4.

Pulmonary angiography of the HHT patients. (A) a large pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (AVM) in patient 2; (B) a new small-sized pulmonary AVM in the right middle lobe in patient 3; (C) multifocal AVM in patient 4; (D) extensive peripheral AVM in patient 5.

Patient 3 experienced a momentary seizure-like movement and a sudden attack of aphasia. A history of frequent epistaxis and chronic anemia was found. At the age of 17, she had a pulmonary segmentectomy because of a pulmonary AVM. She had a family history of recurrent epistaxis (the detailed pedigree could not be obtained). Multiphase contrast-enhanced CT of the brain revealed an occlusion of the left intracranial artery at the middle cerebral artery (MCA) bifurcation level with findings of an acute infarct. Abdominal CT revealed a severe tortuous dilatation of the hepatic artery and its intrahepatic branches with mottled hepatic enhancement (Fig. 3C, D). Chest CT and pulmonary angiography revealed a new small-sized pulmonary AVM in the right middle lobe (Fig. 4B). A wedge resection was performed as a result. The transesophageal echocardiogram revealed a patent foramen ovale.

Patient 4, a 52-yr-old Korean female, was found to have a mass in the right parietal lobe of the brain. She complained of severe headache with fever, chill, nausea and vomiting. She had neck stiffness and microtelangiectasia on the trunk. She had a history of recurrent epistaxis and chronic anemia. There was a family history of epistaxis in her uncle and daughter (detailed pedigree could not be obtained), and her daughter had died suddenly from a hemangioma one year before the patient visited to our hospital. A brain pre- and post-contrast CT showed a rim-enhancing mass in the right parieto-temporal lobe suggesting an abscess with cavity formation. Pulmonary angiography revealed multifocal AVM in both lungs (Fig. 4C). Selective coil embolization of the AVM in the lung was performed, followed by a craniotomy and abscess drainage with the removal of the abscess wall.

Patient 5, a 21-yr-old Korean female, had severe dyspnea and a pulmonary AVM. She had a history of cyanosis, dyspnea, and clubbing of her fingers at birth, as well as multiple AVM in the lung. She underwent a segmentectomy of both lungs at the age of nine. A visual inspection revealed an acneiform eruption on her face, microtelangiectasia on the tongue, and clubbing fingers with one small telangiectasia (Fig. 1E, F). The chest CT and pulmonary angiography revealed extensive peripheral AVM in both lungs (Fig. 4D) and a probable arterioportal shunt involving the liver. Selective coil embolization of the AVM in the lung was performed twice, and the dyspnea was ameliorated.

Mutation analysis

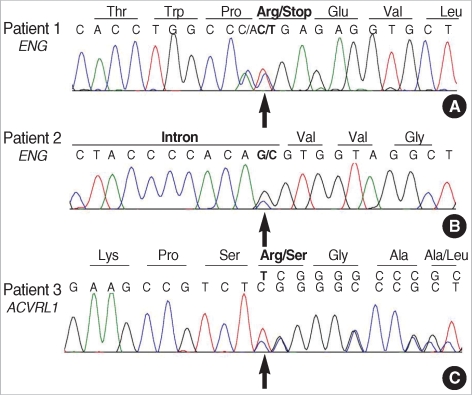

Direct sequencing of the ENG gene was performed initially for all the five patients with HHT. A nonsense mutation producing a premature stop signal at codon 93 (c.277C>T; p.Arg93X) in exon 3 of the ENG gene was found in patient 1, which has previously been reported in HHT-1 patients (23). Patient 2 had a base substitution at a consensus splicing acceptor site of the 9th intron of the ENG gene (c.992-1G>C) predicting a splicing defect. This mutation has not been reported previously. We additionally performed direct sequencing of the ACVRL1 gene for three remaining patients and found one patient with mutation; patient 3 had a novel a frameshift mutation as a result of a duplication of one base pair in the coding region (exon 2) of the ACVRL1 gene producing a premature termination codon (c.81dupT; p.Arg28 SerfsX10) (Fig. 5). We could not perform further genetic analysis on the family members of the patients with mutation.

Fig. 5.

Sequencing results of three mutation-positive patients with HHT. (A) ENG c.277C>T (p.Arg93X) in patient 1; (B) ENG c.992-1G>C (splicing defect) in patient 2; (C) ACVRL1 c.81dupT (p. Arg 28SerfsX10) in patient 3.

Since patients 4 and 5 did not have any mutations in the ENG and ACVRL1 genes, we additionally screened them for the SMAD4 genes, but the results were negative. Subsequent MLPA analysis found no gross deletions in the ENG or ACVRL1 genes in these two patients. Because the P093 HHT/PPH1 MLPA kit also covers the 13 exons of the BMPR2 gene, the causative gene for primary pulmonary hypertension which sometimes shares identical pulmonary manifestations with HHT, we could get additional information on this gene. The remaining two patients showed negative results for the BMPR2 gene.

DISCUSSION

Table 1 gives a summary of the clinical features and results of mutation analysis. All the five patients showed the typical manifestations of HHT with variable individual expression of the clinical features. The onset of epistaxis was rather late in these cases (with the exception of patient 5) compared with normal HHT patients, in whom most manifest recurrent epistaxis before the age of 20 (15, 24). Pulmonary AVM was observed in all five patients, which is believed to be somewhat unusual considering that only 15-30% of HHT patients have pulmonary AVM (15, 25-27). This might be due to the probable selection bias in this study in those patients with severe clinical manifestations such as pulmonary AVM are referred to our hospital for an evaluation of HHT. However, there remains a possibility that high prevalence of pulmonary AVM might be a unique characteristic in Korean patients with HHT; our review of all the literatures addressing Korean patients with HHT found that 13 out of 22 (-59%) patients had pulmonary AVM (28). Further studies on a large set of patients would be needed to clarify these issues, investigating genetic and environmental factors in Korean populations. Patient 5 had relatively severe clinical manifestations such as infantile cyanosis resulting from a congenital pulmonary AVM, which is quite unusual with very few cases (<30) being reported thus far (27, 29). This might be because most cases of congenital AVM are asymptomatic. This suggests that there might be a specific genetic background in this patient.

Molecular analysis of the ENG, ACVRL1, and SMAD4 genes in the five Korean patients with HHT revealed three individuals with mutations in either the ENG or ACVRL1 genes. Endoglin is a membrane protein of the disulphide-linked homodimer that is expressed mainly in the endothelial cells of all vessels. This molecule binds the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which is a powerful mediator of vascular remodeling induced by various stimuli such as vascular wall stress, and forms a signaling heteromeric complex (26, 30). The vast majority (-80%) of mutations of the ENG gene identified in HHT-1 patients are premature stop codons and truncated polypeptides, which appear to act as null alleles resulting in a haploinsufficiency (2). The mutation in patient 1 is a nonsense mutation located in the extracellular domain of the endoglin molecule predicting truncated protein with loss of the transmembrane domain, while patient 2 had a splice site mutation at the highly conserved sequence of the acceptor site of exon 7. Mutation analysis of the family members could not be carried out due to the unavailability of specimens. However, considering the obvious expectation of the abnormal mutant products, those family members with the typical features of HHT are believed to possess the same mutations on the ENG gene. The activin A receptor type II-like 1 encoded by ACVRL1 belongs to the TGF-β superfamily receptor group, which signals through Smad1/5. Moreover, this molecule is expressed almost exclusively in endothelial cells, particularly during angiogenesis (31, 32). Patient 3 had a duplication mutation on exon 2 of the ACVRL1 gene, which is one of mutational hot spot and encodes part of the extracellular domain, predicting a frameshift and very short truncated protein removing the cystein rich (extracellular), transmembrane, kinase, and intracellular domain. The truncation mutations in patient 1 and 3 might fit into the haplo-insufficiency model rather than the dominant-negative model, because the mutant proteins lack the transmembrane domain and they would have less chance to form a heterodimer with normal protein.

There is significant phenotypic variability and genetic heterogeneity in HTT. Sequence analysis of the ENG and ACVRL1 genes reveals mutations in 60-80% of individuals with HHT (33, 34). Several techniques including quantitative PCR, MLPA and southern blot analysis can identify those deletions undetectable by sequence analysis, which can increase the detection rate by up to 10-20% (14, 35). However, mutation analysis of the ENG and ACVRL1 genes can fail to detect mutations in the remaining patients. This suggests the possibility of mutations in the non-coding regions of these genes or mutations in other genes. Recently, linkage analysis in two HHT families identified new HHT loci: HHT-3 in chromosome 5q31.3-32, and HHT-4 in chromosome 7p14 (19, 20). It is possible that patients 4 and 5, who tested negative to mutations in the ENG and ACVRL1 genes, might have mutations in another unidentified gene. Gallione et al. (21) recently reported that mutations in the SMAD4 tumor suppressor gene might be associated with a combined syndrome of JPHT. Because some cases with SMAD4 mutations show clinical manifestations of HHT without juvenile polyposis (36), we screened mutations in the SMAD4 gene in patients 4 and 5, and the results were negative.

HHT occurs with a wide ethnic and geographic distribution. The prevalence of HHT has been reported to range from -1:1,300 to -1:40,000 depending on the geographic or ethnic region (2-9). Moreover, the type and frequency of specific mutations in different localities can vary widely with some regions having a specific founder mutation. For example, a study in France and northern Italy revealed higher frequency (-2.7 times) of HHT-2 than HHT-1 (15). The prevalence of HHT in the Korean population appears to be low with only occasional cases being reported thus far. However, the precise incidence, clinical characteristics, and genetic background of HHT in the Korean population are unknown because no epidemiological surveys have been carried out. Although only a small number of patients were investigated, this study indicates that there might be a specific clinical difference in Korean HHT patients. This highlights the need for more studies on a large set of patients in this regional population. Furthermore, more studies on the genetic background of Korean patients with HHT as well as the identification of another causative gene is needed. It is expected that such studies will help us better understand this serious but overlooked disorder and develop more appropriate therapeutic strategies.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Samsung Biomedical Research Institute grant, # SBRI C-A6-403-2.

References

- 1.Peery WH. Clinical spectrum of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu disease) Am J Med. 1987;82:989–997. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdalla SA, Letarte M. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: current views on genetics and mechanisms of disease. J Med Genet. 2006;43:97–110. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.030833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westermann CJ, Rosina AF, De Vries V, de Coteau PA. The prevalence and manifestations of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia in the Afro-Caribbean population of the Netherlands Antilles: a family screening. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;116:324–328. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.10002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porteous ME, Burn J, Proctor SJ. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: a clinical analysis. J Med Genet. 1992;29:527–530. doi: 10.1136/jmg.29.8.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guttmacher AE, Marchuk DA, White RI., Jr Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:918–924. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510053331407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dakeishi M, Shioya T, Wada Y, Shindo T, Otaka K, Manabe M, Nozaki J, Inoue S, Koizumi A. Genetic epidemiology of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia in a local community in the northern part of Japan. Hum Mutat. 2002;19:140–148. doi: 10.1002/humu.10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kjeldsen AD, Vase P, Green A. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: a population-based study of prevalence and mortality in Danish patients. J Intern Med. 1999;245:31–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bideau A, Plauchu H, Jacquard A, Robert JM, Desjardins B. Genetic aspects of Rendu-Osler disease in Haut-Jura: convergence of methodological approaches of historic demography and medical genetics. J Genet Hum. 1980;28:127–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plauchu H, de Chadarevian JP, Bideau A, Robert JM. Age-related clinical profile of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia in an epidemiologically recruited population. Am J Med Genet. 1989;32:291–297. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320320302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shovlin CL, Guttmacher AE, Buscarini E, Faughnan ME, Hyland RH, Westermann CJ, Kjeldsen AD, Plauchu H. Diagnostic criteria for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome) Am J Med Genet. 2000;91:66–67. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000306)91:1<66::aid-ajmg12>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAllister KA, Grogg KM, Johnson DW, Gallione CJ, Baldwin MA, Jackson CE, Helmbold EA, Markel DS, McKinnon WC, Murrell J, McCormick MK, Pericak-Vance MA, Heutink P, Oostra BA, Haitjema T, Westerman CJ, Porteous ME, Guttmacher AE, Letarte M, Marchuk DA. Endoglin, a TGF-beta binding protein of endothelial cells, is the gene for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Nat Genet. 1994;8:345–351. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson DW, Berg JN, Gallione CJ, McAllister KA, Warner JP, Helmbold EA, Markel DS, Jackson CE, Porteous ME, Marchuk DA. A second locus for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia maps to chromosome 12. Genome Res. 1995;5:21–28. doi: 10.1101/gr.5.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bayrak-Toydemir P, McDonald J, Markewitz B, Lewin S, Miller F, Chou LS, Gedge F, Tang W, Coon H, Mao R. Genotype-phenotype correlation in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: mutations and manifestations. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:463–470. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bossler AD, Richards J, George C, Godmilow L, Ganguly A. Novel mutations in ENG and ACVRL1 identified in a series of 200 individuals undergoing clinical genetic testing for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT): correlation of genotype with phenotype. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:667–675. doi: 10.1002/humu.20342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lesca G, Olivieri C, Burnichon N, Pagella F, Carette MF, Gilbert-Dussardier B, Goizet C, Roume J, Rabilloud M, Saurin JC, Cottin V, Honnorat J, Coulet F, Giraud S, Calender A, Danesino C, Buscarini E, Plauchu H. Genotype-phenotype correlations in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: data from the French-Italian HHT network. Genet Med. 2007;9:14–22. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e31802d8373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Letteboer TG, Mager JJ, Snijder RJ, Koeleman BP, Lindhout D, Ploos van Amstel JK, Westermann CJ. Genotype-phenotype relationship in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Med Genet. 2006;43:371–377. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.035451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berg J, Porteous M, Reinhardt D, Gallione C, Holloway S, Umasunthar T, Lux A, McKinnon W, Marchuk D, Guttmacher A. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: a questionnaire based study to delineate the different phenotypes caused by endoglin and ALK1 mutations. J Med Genet. 2003;40:585–590. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.8.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pece N, Vera S, Cymerman U, White RI, Jr, Wrana JL, Letarte M. Mutant endoglin in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1 is transiently expressed intracellularly and is not a dominant negative. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2568–2579. doi: 10.1172/JCI119800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole SG, Begbie ME, Wallace GM, Shovlin CL. A new locus for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT3) maps to chromosome 5. J Med Genet. 2005;42:577–582. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.028712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayrak-Toydemir P, McDonald J, Akarsu N, Toydemir RM, Calderon F, Tuncali T, Tang W, Miller F, Mao R. A fourth locus for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia maps to chromosome 7. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:2155–2162. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallione CJ, Repetto GM, Legius E, Rustgi AK, Schelley SL, Tejpar S, Mitchell G, Drouin E, Westermann CJ, Marchuk DA. A combined syndrome of juvenile polyposis and hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia associated with mutations in MADH4 (SMAD4) Lancet. 2004;363:852–859. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15732-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergler W, Sadick H, Gotte K, Riedel F, Hormann K. Topical estrogens combined with argon plasma coagulation in the management of epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111(3 Pt 1):222–228. doi: 10.1177/000348940211100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cymerman U, Vera S, Pece-Barbara N, Bourdeau A, White RI, Jr, Dunn J, Letarte M. Identification of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1 in newborns by protein expression and mutation analysis of endoglin. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:24–35. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200001000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haitjema T, Balder W, Disch FJ, Westermann CJ. Epistaxis in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Rhinology. 1996;34:176–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadick H, Sadick M, Gotte K, Naim R, Riedel F, Bran G, Hormann K. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: an update on clinical manifestations and diagnostic measures. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2006;118:72–80. doi: 10.1007/s00508-006-0561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sabba C. A rare and misdiagnosed bleeding disorder: hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:2201–2210. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cottin V, Chinet T, Lavole A, Corre R, Marchand E, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Plauchu H, Cordier JF. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: a series of 126 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007;86:1–17. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31802f8da1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.KoreaMed. Korean Association of Medical Journal Editors. Available at http://www.koreamed.org.

- 29.Butter A, Emran M, Al-Jazaeri A, Bouron-Dal Soglio D, Bouchard S. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation mimicking congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation in a newborn. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:e9–e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Llorca O, Trujillo A, Blanco FJ, Bernabeu C. Structural model of human endoglin, a transmembrane receptor responsible for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:694–705. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.ten Dijke P, Ichijo H, Franzen P, Schulz P, Saras J, Toyoshima H, Heldin CH, Miyazono K. Activin receptor-like kinases: a novel subclass of cell-surface receptors with predicted serine/threonine kinase activity. Oncogene. 1993;8:2879–2887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seki T, Yun J, Oh SP. Arterial endothelium-specific activin receptor-like kinase 1 expression suggests its role in arterialization and vascular remodeling. Circ Res. 2003;93:682–689. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000095246.40391.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lesca G, Plauchu H, Coulet F, Lefebvre S, Plessis G, Odent S, Riviere S, Leheup B, Goizet C, Carette MF, Cordier JF, Pinson S, Soubrier F, Calender A, Giraud S. Molecular screening of ALK1/ACVRL1 and ENG genes in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia in France. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:289–299. doi: 10.1002/humu.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulte C, Geisthoff U, Lux A, Kupka S, Zenner HP, Blin N, Pfister M. High frequency of ENG and ALK1/ACVRL1 mutations in German HHT patients. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:595. doi: 10.1002/humu.9345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cymerman U, Vera S, Karabegovic A, Abdalla S, Letarte M. Characterization of 17 novel endoglin mutations associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Hum Mutat. 2003;21:482–492. doi: 10.1002/humu.10203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallione CJ, Richards JA, Letteboer TG, Rushlow D, Prigoda NL, Leedom TP, Ganguly A, Castells A, Ploos van Amstel JK, Westermann CJ, Pyeritz RE, Marchuk DA. SMAD4 mutations found in unselected HHT patients. J Med Genet. 2006;43:793–797. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.041517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]