Abstract

Polycystic liver is the most common extra-renal manifestation associated with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), comprising up to 80% of all features. Patients with polycystic liver often suffer from abdominal discomfort, dyspepsia, or dyspnea; however, there have been few ways to relieve their symptoms effectively and safely. Therefore, we tried transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE), which has been used in treating hepatocellular carcinoma. We enrolled four patients with ADPKD in Seoul National University Hospital, suffering from enlarged polycystic liver. We embolized the hepatic arteries supplying the dominant hepatic segments replaced by cysts using polyvinyl alcohol particles and micro-coils. The patients were evaluated 12 months after embolization for the change in both liver and cyst volumes. Among four patients, one patient was lost in follow up and 3 patients were included in the analysis. Both liver (33%; 10%) and cyst volume (47.7%; 11.4%) substantially decreased in two patients. Common adverse events were fever, epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting. We suggest that TAE is effective and safe in treating symptomatic polycystic liver in selected ADPKD patients.

Keywords: Polycystic Kidney, Autosomal Dominant; Embolization, Therapeutic

INTRODUCTION

Polycystic liver is the most common extra-renal manifestation associated with autososmal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), presenting in 78.4% of all ADPKD patients (71.7% in male, 83.1% in female) in Korea (1). Most ADPKD patients with polycystic liver are asymptomatic and require no treatment. However, recently hepatic symptoms have become more frequent because of lengthened lifespan of ADPKD patients, and patients with polycystic liver often suffer from abdominal discomfort, dyspepsia, or dyspnea. Several interventions have been tried to relieve these symptoms, including percutaneous cyst aspiration with sclerosis, laparoscopic fenestration, open surgical cyst fenestration, partial hepatectomy, and hepatic transplantation (2). Percutaneous cyst aspiration with sclerosis and laparoscopic fenestration are limited to patients with one or a few very large cysts (3, 4). On the other hand, patients with multiple small cysts can benefit from open surgical cyst fenestration or partial hepatectomy. However, these methods cannot be used for patients with poor nutritional status, massive ascites, or renal failure. Liver transplantation is the best method to solve the problem. But, there are not enough eligible cadaveric donors in Korea. Moreover, surgical procedures would result in morbidity and mortality, reported as high as 42 percent (2, 5).

Recently, Ubara et al. successfully treated symptomatic patients with polycystic liver by selective transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) of hepatic arteries (6, 7). TAE was developed initially for treating hypervascular hepatocellular carcinoma. They focused on the point that hepatic cysts in ADPKD patients are mostly supplied from hepatic arteries but not from portal veins (8). Therefore, they successfully embolized hepatic artery branches that supply major hepatic cysts, leading to shrinkage of the cyst and liver size. There have been only few complications after embolization.

We noticed TAE could be an effective and safe way to relieve mass effects of polycystic liver. Therefore, we designed a pilot study to evaluate the effectiveness and complications of TAE for massive polycystic liver in ADPKD patients. Four ADPKD patients with symptomatic liver cysts were enrolled in the study, and the results in three patients were analyzed 12 months after procedure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This pilot study was designed to relieve severe symptoms caused by massive polycystic liver. Therefore, ADPKD patients with severe symptoms such as ascites, leg edema, dyspepsia, malnutrition or chronic disabling pain not relieved with medical treatment and those who were not able to receive surgical procedures due to poor medical condition were included. All patients were diagnosed and managed in polycystic kidney disease (PKD) clinic, Seoul National University Hospital. ADPKD patients with chronic liver disease or those with aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) higher than 80 IU/L, those with allergy to contrast media, or those with liver cyst infection or other systemic infection were excluded from the study. We obtained approval from our hospital ethics committee for evaluation of a new treatment for symptomatic enlarged polycystic liver. From September 2005 to February 2006, four patients were enrolled in the study and hepatic TAE was performed. After getting informed consent, all patients underwent multiphasic contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the liver before TAE and 12 months after TAE using a multi-detector CT scanner. CT examination was performed using a spiral technique with 1.25- to 2.5-mm collimation and 1-mm reconstruction intervals. The protocol for liver CT required a total volume of 150 mL of nonionic intravenous contrast material (Ultravist, Schering AG, Berlin, Germany; concentration, 370 mg/mL), administered by power injection at a rate of 4 mL/s, and scanned using a bolus-tracking technique. To optimize hepatic arterial enhancement, after injection of contrast material, an auto-triggering technique was used from the aorta at the level of celiac artery. The hepatic arterial phase scan was obtained 6 sec after 100 Hounsfield Units (HU). The portal venous phase scan was obtained 65 sec after contrast administration. The thin-section images were transferred to Rapidia workstation (Infinitt, Seoul, Korea) for three-dimensional reconstruction to calculate liver and cyst volumes.

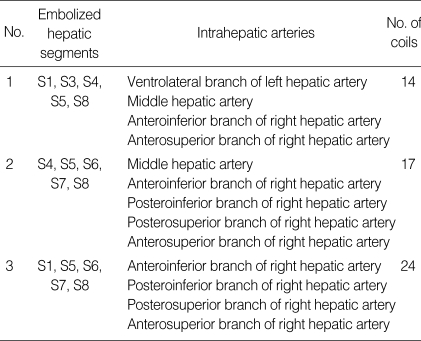

After common femoral artery puncture, celiac axis arteriography was performed by selective catheterization of the celiac axis using a 5-Fr angiographic catheter (RH; Cook, Bloomington, IN, U.S.A.). To precisely define peripheral hepatic arterial anatomy, additional super-selective hepatic arteriographies using a 3-Fr micro-catheter (Microferret; Cook) were performed. Two interventional radiologists interpreted the angiograms and CT images in consensus to decide the target arteries and extent of embolization. Liver is divided into 8 segments. We intended to embolize the hepatic artery supplying the dominant hepatic segments replaced by cysts. Embolized hepatic segments in each patient are listed in Table 3. Targets for TAE included 5 segments in 3 patients, 4 segments in 1 patient.

Table 3.

Embolized hepatic segments and blood supply

S1, Caudate lobe; S2, Dorsolateral segment; S3, Ventrolateral segment; S4, Medial segment; S5, Anteroinferior segment; S6, Posteroinferior segment; S7, Posterosuperior segment; S8, Anterosuperior segment.

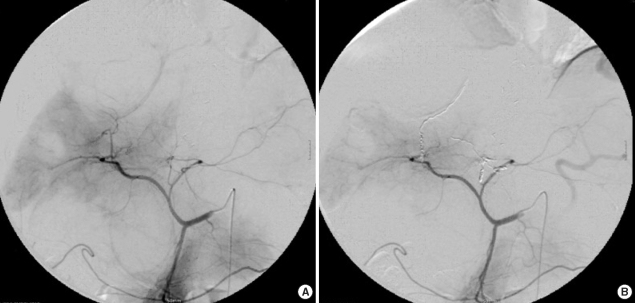

After super-selective catheterization of the target artery, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles (Contour; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, U.S.A.), which range in size from 150 to 250 µm, were used as initial embolic materials for embolization. Injections of PVA particles were performed under direct fluoroscopic visualization until the stasis of contrast material in the target artery. Then, the tip of micro-catheter was advanced as far as possible in the target artery and further embolization was performed with micro-coils (Micronester; Cook) to occlude the target artery completely (Fig. 1). Coils were 3-4 mm in diameter and 14 cm in length. After embolization, celiac axis arteriography was performed to confirm the complete occlusion of the target artery. TAE was performed only once in every patient, and the mean number of micro-coils used for TAE was 16.25 (range, 10 to 24).

Fig. 1.

Transcatheter arterial embolization of selective hepatic artery using PVA particles and micro-coils (Case No.1).

All patients were asked for any change in symptom or subjective feelings after procedure. Also we analyzed any adverse effects occurred during the study.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

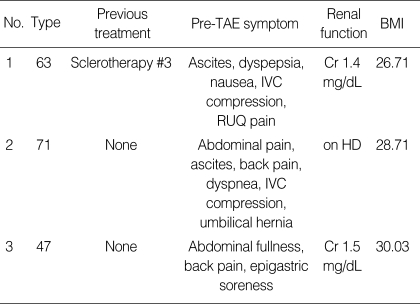

Four patients were enrolled in the study and one patient was lost in follow up after TAE. Therefore, the results in three patients were analyzed. All patients were women with a mean age of 60 yr, ranging from 47 to 71 yr. All of them had severe digestive symptoms related to enlarged liver cysts before TAE, including abdominal pain, nausea, or dyspepsia. One patient also complained of dyspnea (Table 1). These symptoms were intractable even after medical treatment.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

TAE, transcatheter arterial embolization; IVC, Inferior vena cava; RUQ, right upper quadrant; HD, hemodialysis; BMI, Body mass index.

Improvement of subjective symptoms

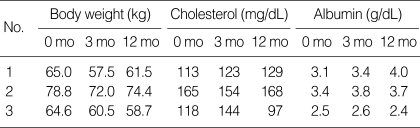

Although no significant improvements were reported immediately after TAE, abdominal discomfort, dyspepsia, and dyspnea were much improved twelve months after TAE. When we evaluated them a year after TAE, two out of three patients regained weight without increased ascites. Nutritional status also improved after TAE, showing improvement in cholesterol and albumin level (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in body weights and nutritional markers after TAE

TAE, transcatheter arterial embolization; mo, months.

Total liver and liver cyst volumes

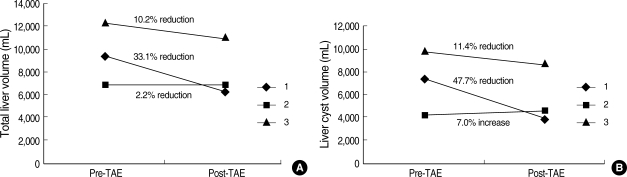

Total liver volume before hepatic TAE was 9,435, 6,872, and 12,164 cm3. Twelve months after TAE, liver volume had decreased to 6,316, 6,718, and 10,921 cm3 respectively, showing as much as 33.1% reduction from pretreatment liver volume (Fig. 2, 3). Total volume of hepatic cysts also decreased in two cases but did not change in one case. Total intra-hepatic cyst volume before TAE was 6,076, 2,839, and 8,184 cm3, and 3,906, 2,892, and 6,131 cm3 respectively twelve months after TAE. TAE was effective in reducing cyst volume, showing as much as 47.7% reduction from pretreatment cyst volume.

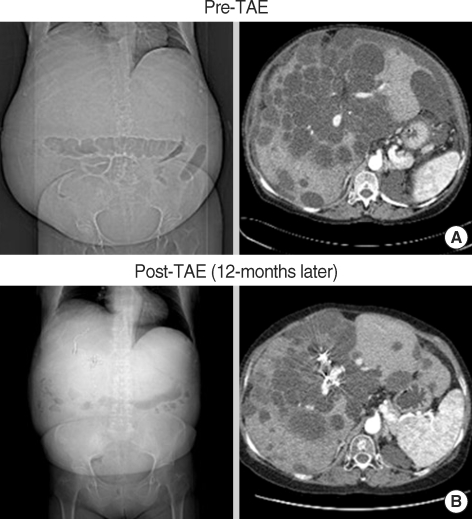

Fig. 2.

Representative computed tomographic images (Case No.1). (A) Before hepatic TAE, this patient's total liver, intra-hepatic cyst, and hepatic parenchymal volumes were 9,435, 6,076, and 3,359 cm3, respectively. Hepatic cysts were numerous and limited to hepatic segment 1, 3, 4, 5, 8. (B) The same patient 12 months after hepatic TAE. Total liver and intra-hepatic cyst volumes decreased to 6,316 and 3,906 cm3, respectively. Hepatic parenchymal volume also decreased to 2,410 cm3 in this patient.

Fig. 3.

(A) Total liver volume before and after hepatic TAE. Total liver volume at 12 month after hepatic TAE decreased in all patients, showing as much as 33% reduction from pretreatment liver volume. (B) Intra-hepatic cyst volume before and after hepatic TAE. Total volume of hepatic cysts decreased in two cases, showing as much as 35% reduction from pretreatment cyst volume.

We also calculated the volume of remaining parenchyma by subtracting the cyst volume from the total liver volume. Total parenchymal volume changed from 3,359, 4,033, 3,980 cm3 to 2,410, 3,826, and 4,790 cm3, respectively. In the last case, the parenchymal volume increased by 20%.

Immediate complications after hepatic TAE

The first patient was hospitalized for 8 days after TAE because of febrile condition and abdominal discomfort. Fever rose up to 38.2℃ without chills and subsided without antibiotics uses after four days. In the second case, the patient was hospitalized for 18 days after procedure, about a week due to procedure-related fever and the other 10 days for non-procedure-related medical problem such as phlebitis. Fever rose up to 39.8℃ with chilling sense immediately after procedure. Moderate to severe epigastric pain and back pain were accompanied. We used empirical antibiotics for 2 weeks, but culture study revealed negative result. Pain was controlled with opioid analgesics and subsided in 5 days after TAE. The third patient was hospitalized for 8 days after procedure because of fever, abdominal pain, nausea, and constipation. Fever occurred two days after TAE up to 39.3℃. Fever was subsided within 1 week of empirical antibiotic therapy. As same as the first case, culture study revealed negative result. Severe nausea and vomiting were controlled with anti-emetics. Mild elevation in AST and ALT was shown in patients immediately after TAE but returned to the normal range in 8 days.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we reported our experience in TAE using PVA particles and micro-coils for massive polycystic liver in ADPKD patients. In two out of three patients, total liver volumes and cyst volumes were reduced substantially by TAE after one year, and TAE improved quality of life for the patients in ways of improving nutritional status and alleviating symptoms from enlarged hepatic cysts.

Massive polycystic liver disease seems female-predominant with known risk factors of multiple pregnancies, use of oral contraceptives and estrogen replacement therapy, suggesting a direct role of estrogen exposure in hepatic cyst growth (9). However, positive correlation between estrogen level and prevalence of hepatic cysts are not proven yet (1, 2).

There have been few effective treatments for symptomatic polycystic liver in ADPKD patients: cyst aspiration with sclerosis, laparoscopic or open cystectomy, segmental hepatectomy, and hepatic transplantation (2, 10). Cyst aspiration with sclerosis can be effective for a few large liver cysts, but patients with multiple small cysts cannot benefit from these therapies (3, 4). Hepatic transplantation can be an effective way to treat symptomatic polycystic liver (6), but, in Korea, there are not many cadaveric donors.

Liver is ordinarily divided into 8 segments according to the Couinaud classification, and each segment is supplied from both hepatic artery and portal vein. In polycystic liver, most portal veins are replaced by cysts and most of blood supplies come from hepatic arteries (6). Therefore, embolization of super-selected hepatic artery for cystic segments can be an easy and effective way to relieve symptoms from enlarged hepatic cysts without serious adverse events.

We designed a pilot study to evaluate the effectiveness and complications of hepatic TAE for polycystic liver in ADPKD patients. Four patients were enrolled in the study, and we measured the liver and hepatic cyst volumes before and after treatment. Hepatic TAE was super-selectively performed using platinum coils and PVA particles. Takei et al. reported use of coils for hepatic TAE to treat symptomatic polycystic liver (3). In addition, we used PVA particles for more distal embolization before deployment of coils to occlude the target arteries completely and to reduce the incidence of collateralization.

Coils have an advantage of being precisely positioned under fluoroscopic visualization. But, collateralization is a potential disadvantage of coil embolization, and it can result in persistent blood flow into the vascular territory of the embolized vessel, reducing therapeutic efficacy. PVA particle is also considered as a permanent embolic agent because of a low incidence in recanalization of the embolized vessels and of its small size that can be delivered more distally than coils in the target artery.

We did not enroll more than four patients in this pilot study because symptoms from massive polycystic liver had not been improved in a short time after TAE and treatment-related immediate complications seemed more severe than anticipated when we analyzed the results one month after TAE. In the previous study of Ubara et al., no serious complications were reported after hepatic TAE (3). However, in our study, immediate complications were severe enough to stop us from recruiting more patients.

The etiology of post-embolization syndrome is not fully understood, but it may be caused by a combination of tissue ischemia and an inflammatory response to embolization. Moderate to severe epigastric pain, fever, severe nausea and vomiting can be an early presentation of post-embolization syndrome, and it can be partly related with the additional use of PVA particles for embolization. Histologically, PVA causes intra-luminal thrombosis associated with an inflammatory reaction, with subsequent organization of the thrombus.

Embolization with both PVA particles and coils can cause more severe post-embolization syndrome than coil embolization. Therefore, further studies are needed to evaluate the most effective embolization materials and techniques to increase the therapeutic efficacy and to reduce the early complications.

Despite early complications, hepatic TAE in selected patients was effective and safe on a long-term follow-up. In two out of three patients, the total liver volumes decreased by 10% and 33%, and the cyst volumes decreased by 11.4% and 47.7%. There was no treatment-related morbidity or mortality at one year after TAE. Takei et al. performed hepatic TAE in 30 patients and reported that total liver volume and intra-hepatic cyst volume decreased from 7,882±2,916 and 6,677±2,978 to 6,041±2,282 and 4,625±2,299 cm3 (6). The fractions of remaining liver volume and intra-hepatic cyst volume were 78.8±17.6% and 70.4±20.9%. Our results were comparable to those in the previous study.

In conclusion, we suggest that hepatic TAE can be effective and safe way to treat symptomatic polycystic liver in selected patients. There should be a large, randomized study to define the effectiveness and complications of hepatic TAE.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the grant from the Seoul National University Hospital (Grant No. 09-2000-008-0).

References

- 1.Hwang DY, Ahn C, Lee JG, Lee EJ, Cho JT, Hwang YH, Eo HS, Chae HJ, Kim SJ, Kim Y, Han JS, Kim S, Lee JS, Kim SH. Hepatic complications in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease; 20th Annual Spring Conference of Korean Society of Nephrology; Seoul, Korea. 2000. p. S306. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chauveau D, Fakhouri F, Grunfeld JP. Liver involvement in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: therapeutic dilemma. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:1767–1775. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1191767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erdogan D, van Delden OM, Rauws EA, Busch OR, Lameris JS, Gouma DJ, van Gulik TM. Results of percutaneous sclerotherapy and surgical treatment in patients with symptomatic simple liver cysts and polycystic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3095–3100. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i22.3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson TN, Stiegmann GV, Everson GT. Laparoscopic palliation of polycystic liver disease. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:130–132. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold HL, Harrison SA. New advances in evaluation and management of patients with polycystic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2569–2582. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takei R, Ubara Y, Hoshino J, Higa Y, Suwabe T, Sogawa Y, Nomura K, Nakanishi S, Sawa N, Katori H, Takemoto F, Hara S, Takaichi K. Percutaneous transcatheter hepatic artery embolization for liver cysts in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:744–752. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ubara Y, Takei R, Hoshino J, Tagami T, Sawa N, Yokota M, Katori H, Takemoto F, Hara S, Takaichi K. Intravascular embolization therapy in a patient with an enlarged polycystic liver. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:733–738. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ubara Y. New therapeutic option for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease patients with enlarged kidney and liver. Ther Apher Dial. 2006;10:333–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2006.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherstha R, McKinley C, Russ P, Scherzinger A, Bronner T, Showalter R, Everson GT. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy selectively stimulates hepatic enlargement in women with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Hepatology. 1997;26:1282–1286. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torres VE. Treatment of polycystic liver disease: one size does not fit all. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:725–728. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]