Abstract

Organochlorine exposure was linked to non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) risk. To determine whether this relation is modified by immune gene variation, we genotyped 61 polymorphisms in 36 immune genes in 1172 NHL cases and 982 controls from the National Cancer Institute–Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (NCI-SEER) study. We examined 3 exposures with elevated risk in this study: PCB180 (plasma, dust measurements), the toxic equivalency quotient (an integrated functional measure of several organochlorines) in plasma, and α-chlordane (dust measurements, self-reported termiticide use). Plasma (100 cases, 100 controls) and dust (682 cases, 513 controls) levels were treated as natural log-transformed continuous variables. Unconditional logistic regression was used to calculate β coefficients and odds ratios, stratified by genotype. Associations between all 3 exposures and NHL risk were limited to the same genotypes for IFNG (C−1615T) TT and IL4 (5′-UTR, Ex1-168C>T) CC. Associations between PCB180 in plasma and dust and NHL risk were limited to the same genotypes for IL16 (3′-UTR, Ex22+871A>G) AA, IL8 (T−251A) TT, and IL10 (A−1082G) AG/GG. This shows that the relation between organochlorine exposure and NHL risk may be modified by particular variants in immune genes and provides one of the first examples of a potential gene-environment interaction for NHL.

Introduction

Organochlorine compounds such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dioxins, furans, and certain pesticides are ubiquitous environmental pollutants that accumulate in adipose tissue. Several epidemiologic studies have suggested that organochlorine compounds may play a role in the development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).1–11 The National Cancer Institute–Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (NCI-SEER) population-based case-control study of NHL, the parent study for the current analysis, examined these compounds with the use of data from questionnaires about termiticide use and analysis of plasma and carpet dust samples for organochlorine compounds. PCB180 levels in plasma4 and carpet dust2 were positively associated with NHL risk, as were plasma levels of PCB156 and PCB194, the coplanar PCB169, total furans and several individual furan congeners, and the toxic equivalency quotient (TEQ, a toxicity-weighted summary metric indicating biologic activity through the arylhydrocarbon receptor pathway).4 NCI-SEER study participants were also at increased risk of developing NHL if levels of the termiticide chlordane were elevated in their carpet dust, or if their homes had been treated for termites before the 1988 ban on chlordane in the United States.3 Although the association between particular organochlorines, or organochlorines as a class, and risk of NHL has not been established, the epidemiologic data are highly suggestive. There is a substantial amount of data, predominantly experimental, showing that these compounds can influence immune function.12–17

Common variants in immune and inflammatory response genes have been associated with NHL risk in several studies.18–23 Consistent main effect associations with NHL have been reported for one or more polymorphisms in tumor necrosis factor (TNF)20,21,23 and interleukin-10 (IL10),19–21,23 with growing evidence for interleukin-4 (IL4).19,20

The identification of variants in one or more immune genes influencing NHL risk, and the epidemiologic and experimental evidence suggesting an association between organochlorine exposures and NHL, led us to evaluate the relation between organochlorine exposures and NHL risk according to the presence or absence of polymorphisms in a wide spectrum of immune and inflammatory response genes. We previously reported the effects of organochlorine exposure limited to genotypes of IL10 and TNF24; here, we evaluate more broadly the relation between these exposures and genetic variants in 36 genes.

Methods

Study population

The study population was described previously.25 Cases included 1321 patients newly diagnosed with NHL at ages 20 to 74 between July 1, 1998, and June 30, 2000, at 4 SEER registries (the state of Iowa, Los Angeles County, and the metropolitan areas of Detroit and Seattle). Population controls (n = 1057), frequency-matched to cases on age, sex, race, and SEER registry were identified by random digit dialing (younger than age 65) or Medicare files (age 65 and older). Overall participation rates were 76% in cases and 52% in controls; overall response rates were 59% and 44%, respectively. The study was approved by human subjects review boards at all participating institutions, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant before interview in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All cases were histologically confirmed and coded according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 2nd edition.26

Exposure assessment

Participants were mailed a residential and occupational history calendar. During the subsequent home visit, the interviewer administered a computer-assisted personal interview that included a detailed history of pest treatment in each residence occupied for 2 years or more since 1970. Among the questions asked was whether any of the homes had been treated for termites and, if so, whether the treatment occurred before or after 1988. Used vacuum cleaner bags were collected from eligible participants and sent to Southwest Research Institute (San Antonio, TX), where dust samples (682 cases and 513 controls meeting eligibility criteria) were analyzed for insecticides and PCBs.2,3,27 A multiple imputation procedure was used to assign values to missing data2,28; in the present analysis, we use values from one of those imputations. We include in the current analysis the 2 analytes whose levels in carpet dust were significantly associated with NHL risk: PCB1802 and α-chlordane.3

Interviewed participants were asked to provide a venous blood or mouthwash buccal cell sample. From a subset of 100 untreated cases and 100 controls with blood samples, we measured persistent organochlorine chemical levels in plasma4 (approximately one-half of these participants also had dust measurements for organochlorines). A multiple imputation procedure was used to assign values to missing data determined to be below the detection limits; as with dust, we used one of those imputations for the current analysis. We include PCB180 in the current analysis because its levels in both plasma and carpet dust were significantly associated with NHL risk. We also include the TEQ, which was calculated as the sum of the lipid-adjusted levels of dioxin, furan, coplanar PCB, and mono-ortho-chlorinated PCB congeners, each weighted by its congener-specific toxicity equivalency factor (TEF, congener potency relative to TCDD). The TEQ calculation is based on 11 congeners for which World Health Organization TEFs have been assigned (PCB180 is not among them) and that were detected in at least 30% of the plasma samples.4,29,30 We chose to include the TEQ rather than its individual components because the latter are highly correlated.

We genotyped blood samples from 773 cases and 668 controls and buccal cell samples from 399 cases and 314 controls, as previously described.23 We identified for analysis 61 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 36 proinflammatory and other immunoregulatory genes (Table 1). As previously reported,23 these variants were selected according to a priori laboratory evidence that suggested functional consequences for an allele or reported associations with NHL or related risk factors (eg, autoimmune disorders, infectious diseases). Genotyping was conducted at the NCI Core Genotyping Facility (Gaithersburg, MD), as previously described.23 Agreement for 40 blinded quality control replicates and 100 blinded duplicates was at least 99% for all assays. Successful genotyping was achieved for 96% to 100% of DNA samples for all SNPs.

Table 1.

Inflammatory response and other immunoregulatory genes and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) evaluated

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Location | Alias (SNP500 location) | RS no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL1A | Interleukin 1-α | 2q13 | A114S (Ex5+21G>T), C−889T (Ex1+12C>T) | rs17561*, rs1800587* |

| IL1B | Interleukin 1-β | 2q14 | C−511T, C3954T or F105F, C−31T | rs16944*, rs1143634*, rs1143627* |

| IL1RN | Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist | 2q14.2 | A9589T | rs454078* |

| IL8RB | Interleukin 8 receptor β | 2q35 | (3′-UTR, Ex3+1235T>C), (3′-UTR, Ex3-1010G>A), L262L (Ex3+811C>T) | rs1126579*, rs1126580*, rs2230054* |

| Interleukin 8 | 4q12-q13 | T-251A, (IVS1+230G>T), (IVS1−204C>T) | rs4073*, rs2227307*, rs2227306* | |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor | 6p21.3 | G−308A, G−238A, C-857T, A−863C | rs1800629*, rs361525*, rs1799724*, rs1800630† |

| LTA | Lymphotoxin-α | 6p21.3 | A252G C−91A | rs909253*, rs2239704* |

| IL6 | Interleukin 6 | 7p15.3 | G−174C, G−597A or G−598A | rs1800795*, rs1800797* |

| IL16 | Interleukin 16 | 15q25.1 | 3′-UTR, Ex22+871A>G, 3′-UTR, Ex22+889G>T | rs859*, rs11325* |

| VCAM1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 | 1p32-p31 | T−1591C, K644K (Ex9+149G>A) | rs1041163*, rs3176879* |

| FCGR2A | Receptor for Fc fragment of IgG, low-affinity IIa (CD32) | 1q21-q23 | H165R (Ex4−120A>G) | rs1801274* |

| SELE | Selectin E | 1q22-q25 | S149R (Ex4+24A>C) | rs5361* |

| IL10 | Interleukin 10 | 1q31-q32 | C−819T, C−592A, A−1082G, T−3575A | rs1800871*, rs1800872*, rs1800896*, rs1800890* |

| STAT1 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 | 2q32.2-q32.3 | IVS21−8C>T (splice) | rs2066804* |

| CTLA4 | Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated 4 | 2q33 | T17A (Ex1−61A>G) | rs231775* |

| CCR2 | Chemokine, CC motif, receptor 2 | 3p21 | V64I (Ex2+241G>A) | rs1799864* |

| CCR5 | Chemokine, CC motif, receptor 5 | 3p21 | Δ32 | rs333* |

| CX3CR1 | Chemokine, CXC motif | 3p21 | V249I (Ex2+754G>A) | rs3732379* |

| IL12A | Interleukin 12, α | 3q25.33 | G8685A | rs568408* |

| IL2 | Interleukin 2 | 4q26-q27 | Ex2T>G | rs2069762* |

| IL15 | Interleukin 15 | 4q31.21 | 3′-UTR, Ex9−66T>C | rs10833* |

| IL7R | Interleukin 7 receptor (CD127) | 5p13 | V138I (Ex4+33G>A) | rs1494555* |

| IL13 | Interleukin 13 | 5q23.3 | Q144R (Ex4+98A>G), C−1069T | rs20541*, rs1800925* |

| IL4 | Interleukin 4 | 5q31.1 | C−524T, T−1098G, 5′-UTR, Ex1-168C>T | rs2243250*, rs2243248*, rs2070874* |

| IL5 | Interleukin 5 | 5q31.1 | C−745T, C−1551T, Ex4+78C>A | rs2069812*, rs2069807*, rs2069818† |

| IL12B | Interleukin 12B | 5q33.3 | 3′-UTR, Ex8+159A>C | rs3212227* |

| IFNGR1 | Interferon γ receptor 1 | 6q23-q24 | IVS6−4G>A | rs3799488* |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 | 9q32-q33 | D299G (Ex4+636A>G) | rs4986790* |

| IL15RA | Interleukin 15 receptor α | 10p15.1 | 3′-UTR, Ex8−361A>C | rs2296135* |

| CXCL12 | Chemokine, CXC motif, ligand 12 (SDF-1) | 10q11.1 | 3′-UTR, Ex4+535C>T | rs1801157* |

| IL10RA | Interleukin 10 receptor α | 11q23.3 | 3′-UTR, Ex7−109G>A | rs9610* |

| IL4R | Interleukin 4 receptor | 16p12.1-p11.2 | C−29429T | rs2107356* |

| JAK3 | Janus kinase 3 | 19p13.1 | 3′-UTR, Ex23+291A>G, IVS2+42G>A, IVS2+40G>A | rs3008*, rs3212713†, rs3212712† |

| ICAM1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 | 19p13.3-p13.2 | K56M (Ex2+100A>T) | rs5491* |

| IFNG | Interferon γ | 21q14 | IVS3+284G>A, C−1615T | rs1861494*, rs2069705* |

| IFNGR2 | Interferon γ receptor 2 | 21q22.1-q22.2 | Q64R (Ex2−16A>G) | rs9808753* |

Statistical analysis

Measurements in carpet dust (PCB180 and α-chlordane) and plasma (PCB180 and TEQ) were log-normally distributed and were treated as natural log-transformed continuous variables in the analysis. Unconditional logistic regression models were used to calculate the β coefficient and P value for each risk factor, stratified by dichotomized genotype. We report the results as the percentage increase in NHL risk for each 10% increase in the exposure level, which was calculated as exp(β × ln[1.1]). We calculated the P for interaction based on the log-transformed continuous variable for each risk factor and the scored variable for dichotomized genotype.

Termite treatment before 1988 was analyzed as a categorical variable. The referent group comprised persons whose homes had never been treated for termites or had been treated only after 1988, and the exposed group was composed of persons with at least one termite treatment before 1988. We excluded from the analysis people who responded “don't know” for all of their homes, people who could not recall whether one or more of their homes had been treated for termites (but knew that the others had not), and people who could not remember when the treatments occurred. We used unconditional logistic regression models to calculate ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the joint effect of termite treatment and dichotomized genes. We calculated P for interaction based on the scored variable for termite treatment and for dichotomized genotype.

All risk estimates were adjusted for the study design variables sex, age (<45, 45-64, ≥65 years), race (white, other/unknown), education (<12, 12-15, >15 years), and study center. Logistic regression models were conducted using SAS 9.13 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

We used the following criteria to identify findings of possible significance. For PCB180, we first identified SNPs for which (1) PCB180 levels in both plasma and carpet dust were significantly associated at P less than .05 with NHL risk in the same genotype, or (2) PCB 180 levels in either plasma or carpet dust were highly significantly associated at P values less than .01 with NHL risk for one of the genotypes. Similarly, for α-chlordane, which was also assessed 2 ways (carpet dust measurements and termiticide use), we identified SNPs for which both measures were significantly associated at P values less than .05 with NHL risk in the same genotype, or either measure was highly significantly associated at P values less than .01 with NHL risk in one of the genotypes. We further imposed the criterion that the genotype conferring increased NHL risk must be consistent for both measures of the same exposure. For plasma TEQ, we selected SNPs for which one genotype was significantly associated at P values less than .01 with NHL risk.

Sixteen SNPs met at least one of these criteria (see Tables S1,S2, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Tables link at the top of the online article); results for the remaining 45 SNPs are shown in Tables S3 and S4. To assist in interpretation of these findings, we summarize the main effects of the exposures among cases and controls with genotype data in Table 2.

Table 2.

Association between organochlorine exposure and NHL risk in the NCI-SEER study, all genotypes

| Exposure | Entire study population |

Individuals with genetic information |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca/Co | Relative risk (95% CI), %* | OR (95% CI) | P | Ca/Co | Relative risk (95% CI), %* | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Treated for termites before 1988† | 220/162 | — | 1.3 (1.0-1.6) | .069 | 196/147 | — | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) | .12 |

| α-Chlordane in carpet dust (ng/g) | 682/513 | 0.6 (0.0-1.2) | — | .051 | 607/462 | 0.6 (0.0-1.2) | — | .067 |

| PCB180 in carpet dust (ng/g) | 682/513 | 0.7 (0.0-1.3) | — | .041 | 607/462 | 0.7 (0.0-1.4) | — | .041 |

| PCB180 in plasma (pg/g lipid) | 100/100 | 8.3 (1.9-14.6) | — | .009 | 93/96 | 8.5 (1.7-15.1) | — | .011 |

| TEQ in plasma (pg/g lipid) | 96/95 | 7.8 (1.1-17.2) | — | .022 | 90/91 | 8.0 (1.0-15.5) | — | .025 |

NHL indicates non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NCI-SEER, National Cancer Institute–Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PCB, polychlorinated biphenyl; and TEQ, toxic equivalency quotient.

Increase in risk of NHL for each 10% increase in exposure.

Referents are participants whose homes were never treated for termites or were treated only after 1988.

Results

Among the 16 SNPs meeting the stated criteria, IFNG was noteworthy for its consistent effect on NHL risk across all of the exposures (Figure 1, Table 3). Specifically, we observed significant elevations in risk from PCB180 exposure among IFNG (C−1615T) TT homozygotes for measurements in both plasma (16.9% increase in risk for each 10% increase in pg/g lipid) and carpet dust (1.2% increase in risk for each 10% increase in ng/g), from plasma TEQ (19.2% increase in risk), and from α-chlordane in carpet dust (1.1% increase in risk); for termite treatment there was a 50% elevation in risk that was of borderline statistical significance. In contrast, no significant elevations in risk for any of the exposures evaluated were observed among carriers of the variant allele. No statistically significant interactions were observed between genotype and these exposures for this SNP.

Figure 1.

Exposure to 5 measures of organochlorine exposure and NHL risk, stratified by genotype. Exposure and NHL risk was stratified by genotype for 2 single nucleotide polymorphisms: IFNG C−1615T (A) and IL4 5′-UTR, Ex1−168T (B). One asterisk (*) denotes significant association (P < .05) between exposure and NHL risk for that genotype. Two asterisks (**) denote highly significant association (P < .01) between exposure and NHL risk for that genotype. P value accompanies x-axis label if there was a significant interaction (P for interaction < .05) between genotype and exposure; y-axis is β coefficient from logistic regression.

Table 3.

NHL risk and exposure to organochlorines, stratified by genotype for selected single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)

| SNP genotype | PCB180 in plasma, pg/g lipid |

PCB180 in carpet dust, ng/g |

TEQ in plasma, pg/g lipid |

α-Chlordane in carpet dust, ng/g |

Termite treatment before 1988 |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca/Co* | NHL risk (95% CI), %† | P | P for inter-action | Ca/Co* | NHL risk (95% CI), %† | P | P for inter-action | Ca/Co* | NHL Risk (95 CI), %† | P | P for inter-action | Ca/Co* | NHL risk (95 CI), %† | P | P for inter-action | Ca/Co* | OR (95 CI)‡ | P for inter-action | ||

| IFNG C−1615T | .12 | .48 | .30 | .099 | .29 | |||||||||||||||

| TT | 39/46 | 16.9 (3.7-31.6) | .010 | 243/188 | 1.2 (0.1-2.4) | .033 | 39/45 | 19.2 (4.8-35.7) | .008 | 243/188 | 1.1 (0.1-2.1) | .030 | 379/319 | 1.5 (1.0-2.3) | ||||||

| CT/CC | 53/50 | 3.8 (−4.0-12.2) | .35 | 333/245 | 0.5 (−0.5-1.4) | .34 | 50/46 | 2.6 (−5.4-11.3) | .53 | 333/245 | 0.1 (−0.7-0.9) | .77 | 508/421 | 1.1 (0.7-1.5) | ||||||

| IL4 5′-UTR, Ex1−168C>T | .21 | .21 | .021 | .50 | .85 | |||||||||||||||

| CC | 62/64 | 9.3 (0.9-18.3) | .030 | 403/294 | 1.0 (0.1-1.9) | .027 | 60/61 | 12.5 (3.0-22.9) | .009 | 403/294 | 0.6 (−0.2-1.4) | .14 | 634/490 | 1.3 (1.0-1.9) | ||||||

| CT/TT | 30/29 | 3.0 (−7.9-15.1) | .61 | 192/159 | 0.1 (−1.1-1.4) | .84 | 29/27 | 0.4 (−13.2-16.1) | .96 | 192/159 | 0.3 (−0.7-1.4) | .57 | 287/275 | 1.0 (0.6-1.5) | ||||||

| IL16 3′-UTR, Ex22+871A>G | .002 | .11 | .66 | .77 | .24 | |||||||||||||||

| AA | 46/48 | 15 (3.2-28.0) | .011 | 330/230 | 1.1 (0.1-2.1) | .029 | 44/44 | 11.2 (−0.3-24.0) | .057 | 330/230 | 0.5 (−0.3-1.4 | .25 | 478/376 | 1.2 (0.8-1.7) | ||||||

| AG/GG | 45/45 | 0.5 (−8.5-10.4) | .91 | 254/218 | 0.2 (−0.9-1.2) | .76 | 44/44 | 10.3 (−1.3-23.4) | .085 | 254/218 | 0.5 (−0.5-1.4) | .33 | 424/376 | 1.1 (0.8-1.7) | ||||||

| IL8 T−251A | .063 | .36 | .80 | .28 | .98 | |||||||||||||||

| TT | 27/29 | 28.9 (6.4-56.1) | .010 | 172/131 | 1.4 (0.05-2.8) | .043 | 27/28 | 8.8 (−4.4-23.9) | .20 | 172/131 | 0.3 (−0.8-1.5) | .60 | 246/216 | 1.3 (0.8-2.2) | ||||||

| AT/AA | 64/67 | 4.8 (−2.2-12.3) | .19 | 401/300 | 0.5 (−0.4-1.4) | .27 | 61/63 | 9.1 (0.4-18.6) | .041 | 401/300 | 0.6 (−0.2-1.4) | .12 | 637/522 | 1.2 (0.9-1.7) | ||||||

| IL10 A−1082G | .14 | .37 | .97 | .53 | .67 | |||||||||||||||

| AA | 31/28 | 6.6 (−5.1-19.7) | .28 | 168/144 | 0.5 (−0.8-1.8) | .44 | 30/25 | 15.8 (−1.5-36.0) | .075 | 168/144 | 0.2 (−0.9-1.4) | .71 | 266/239 | 1.1 (0.6-1.7) | ||||||

| AG/GG | 59/66 | 9.9 (1.2-19.4) | .025 | 431/309 | 0.9 (0.05-1.8) | .038 | 57/64 | 5.0 (−3.0-13.8) | .23 | 431/309 | 0.6 (−0.2-1.3) | .13 | 651/530 | 1.2 (0.9-1.7) | ||||||

NHL indicates non-Hodgkin lymphoma; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PCB, polychlorinated biphenyl; and TEQ, toxic equivalency quotient.

Number of cases and controls included in the risk analysis for that genotype.

Increase in NHL risk for each 10% increase in exposure level.

Referents were participants whose homes were never treated for termites or were treated only after 1988.

IL4 also showed evidence of a broad effect across exposures. The IL4 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR), Ex1−168C>T polymorphism interacted significantly with plasma TEQ, with significantly elevated risk observed only among persons with the more common genotype (CC; 12.5% increase in risk for each 10% increase in pg/g lipid of TEQ). CC homozygotes, but not those with the CT or TT genotype, had significantly increased NHL risk from PCB180 exposure, regardless of whether exposure was evaluated in plasma or carpet dust. The associations between NHL risk and both measures of chlordane exposure were also higher among CC homozygotes; the association for termite treatment was of borderline statistical significance.

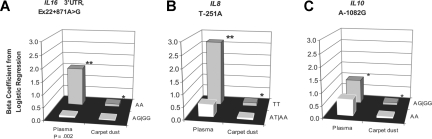

Associations specific to PCB180, as measured in both plasma and carpet dust, and risk of NHL were limited to the same genotype for 3 additional genes: IL16 (3′-UTR, Ex22+871A>G), IL8 (T−251A), and IL10 (A−1082G; Figure 2). The IL16 3′-UTR, Ex22+871A>G SNP significantly modified the association between plasma PCB180 levels and NHL risk, with elevated risk restricted to the more common genotype (AA; 15.0% increase in risk for each 10% increase in pg/g lipid of PCB180); PCB180 levels in carpet dust were also significantly associated with NHL risk only for this genotype (1.1% increase), although the interaction was not significant. We also observed significant elevations in risk from PCB180 exposure only among IL8 (T−251A) TT homozygotes for measurements in both plasma (28.9% increase in risk for each 10% increase in pg/g lipid) and carpet dust (1.4% increase in risk for each 10% increase in ng/g). Finally, only those persons carrying a variant allele for the IL10 (A−1082G) polymorphism had significantly elevated risk from PCB180 exposure, regardless of whether exposure was measured in plasma or carpet dust.

Figure 2.

Exposure to PCB180 levels in plasma and carpet dust and NHL risk, stratified by genotype. Exposure and NHL risk was stratified by genotype for 3 single nucleotide polymorphisms: IL16 3′-UTR, Ex22+871A>G (A), IL8 T−251A (B), and IL10 A−1082G (C). One asterisk (*) denotes significant association (P < .05) between exposure and NHL risk for that genotype. Two asterisks (**) denote highly significant association (P < .01) between exposure and NHL risk for that genotype. P value accompanies x-axis label if there was a significant interaction (P for interaction < .05) between genotype and exposure; y-axis is β coefficient from logistic regression.

For each polymorphism listed in Table 3, we also examined potential interactions between genotype and plasma levels of PCB156 and PCB194, which were significantly associated with NHL risk in the main study4 but were not measured in carpet dust. For each SNP, the genotype that had a significant association for PCB180 levels in plasma and carpet dust also had a significant association for PCB194, with significant interactions for IL8 (T−251A; P = .025) and IL16 (3′-UTR, Ex22+871A>G; P = .001; data not shown). For all of the SNPs except IL10 (A−1082G), significant associations were also observed in the same genotype for plasma PCB156, with significant interactions for IFNG (C−1615T; P = .007) and IL16 (3′-UTR, Ex22+871A>G; P = .030; data not shown).

Discussion

We examined potential interactions between exposure to organochlorine compounds and SNPs in genes involved in immune and inflammatory response. Our analysis suggests that IFNG and IL4 broadly affect the relation between organochlorine exposure and NHL risk, whereas the effects of IL16, IL8, and IL10 appear to be limited to PCB180. Overall, our findings suggest that organochlorines may affect NHL risk at least in part through biologic mechanisms involving immune effects.

Exposure to PCBs, dioxins, and furans can lead to adverse effects on immune, reproductive, neurobehavioral, and endocrine functions.17,31,32 Their effects on the immune system are of particular interest because immune alteration is a known risk factor for NHL. Experiments with laboratory animals and nonhuman primates have shown that dioxin exposure can lead to cellular and humoral immune suppression, increased susceptibility to infectious disease, thymus atrophy, and depressed antibody and lymphoproliferative responses.15 Exposure to PCBs and dioxins has been found to diminish host resistance to infection, resulting in increased disease incidence and severity.15 Prenatal exposure to these compounds was associated with changes in the T-cell lymphocyte population in Dutch infants.16 In Dutch preschool children, PCB body burden was associated with recurrent middle-ear infections and chickenpox.17 In Flemish adolescents, biomarkers of internal exposure to dioxin-like compounds were related to biomarkers of immune status, and exposure to these compounds was associated with a lower prevalence of allergic diseases15; interestingly, a history of allergies was associated with a reduced risk of NHL in the NCI-SEER study.33

Data also indicate that chlordane and its constituents have effects on the immune system. In an experimental mouse model, Tryphonas et al14 found that cis-nonachlor increased IgG levels, although chlordane itself had no effect. Both cis-nonachlor and trans-nonachlor led to an increased susceptibility for mice to bacterial infection, suggesting that the chemicals are immunosuppressing. In humans, exposure to chlordane was associated with decreased lymphocyte responsiveness and the frequent presence of autoantibodies.12

IL4 and IL10 were previously reported to be associated with risk of NHL or its subtypes.19–21 Both play roles in one or more processes associated with lymphocyte development and immune function. IL-4 regulates B-cell proliferation and immunoglobulin (Ig) class switching,34 and it is a key component in the induction of the Th2 lymphocyte phenotype and the down-regulation of the Th1 lymphocyte phenotype.35 There is compelling evidence that variants in IL10 play an important role in the cause of NHL.19–21 The IL10 A-1082G polymorphism is believed to result in higher production of IL-10,36,37 and it has been postulated that IL-10, as a B-cell stimulatory cytokine, may promote lymphomagenesis.38 In support of this hypothesis is evidence that a putatively high IL-10 expressing genotype (−592 CC) is associated with increased risk of AIDS-associated NHL.20,38 In addition, elevated levels of IL-10 in the vitreous have been correlated with primary intraocular lymphoma.19,39 We are unaware of previous reports of associations between NHL risk and IFNG, IL16, or IL8 polymorphisms.

Interaction between organochlorine exposure and immune gene variation is plausible, given the observed effects of organochlorines on the immune system, the known relation between immune alteration and NHL risk, and the observed associations between common variants in immune and inflammatory response genes and NHL risk. We believe that our findings are notable but require replication in a large independent effort before further speculation about the potential mechanisms involved in NHL risk.

A strength of our study is the systematic approach taken to evaluate the joint effects of exposure to organochlorines and a wide variety of genetic polymorphisms. Case ascertainment using SEER tumor registries ensured that few were missed, and the use of population controls minimized biases typically associated with hospital-based case-control studies. Our multifaceted approach toward exposure assessment (ie, questionnaire, blood samples, carpet dust samples) allowed us to evaluate the consistency of our results across various exposure assessment methods.

A limitation of the study is the low statistical power for estimating the combined effects of genetic polymorphisms and some of the less common risk factors. Another shortcoming is that genetic variability of inflammatory/immune pathways is not completely explained by the genes and SNPs studied here. Other limitations include low response rates (typical of current population-based studies), possible misclassification in the exposure data, possible confounding, and the possibility that multiple comparisons testing produced false-positive findings, although this is unlikely for the SNPs we have highlighted because of their consistency across multiple exposures. Finally, it is possible that the SNPs producing the effects observed in the study are in linkage disequilibrium with other variants that could confer the observed biologic effect.

In summary, our exploratory results require replication in additional large studies and in pooled analyses. However, they provide evidence that organochlorine exposure may pose a differential risk of NHL to persons according to variability in genes involved in immune and inflammatory response.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our study participants for their involvement. We thank Carol Haines (Westat) for development of study materials and procedures, for selection of younger controls, and for study coordination; Lonn Irish (IMS) for computer programming support; Carla Chorley (BBI Biotech Research Laboratories) for specimen handling; and Geoffrey Tobias for research assistance.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health at the NCI and by contracts with the NCI (NCI-SEER contracts N01-CN-67008, N01-CN-67010, N01-PC-67009, and N01-PC-65064; NCI-Southwest Research Institute contract N02-CP-19 114; and NCI-CDC interagency agreement Y1-CP-8028-02).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: P.H. was the principal investigator of the NCI-SEER NHL study; R.K.S., J.R.C., W.C., and S.D. obtained questionnaire and cancer outcome data from the 4 NCI-SEER registries; J.S.C. obtained dust sampling data; N.R. and A.J.D.R. obtained plasma organochlorine data; S.C. supervised genotyping at the NCI Core Genotyping Facility; J.S.C. performed the statistical analysis with input from S.S.W., N.R., P.H., L.M.M, and N.C.; and J.S.C., S.S.W., and N.R. drafted and revised the paper. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Joanne S. Colt, National Cancer Institute, Occupational and Environmental Epidemiology Branch, 6120 Executive Boulevard, Room 8112, Bethesda, MD 20892-7240; e-mail: coltj@mail.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Bertazzi A, Pesatori AC, Consonni D, Tironi A, Landi MT, Zocchetti C. Cancer incidence in a population accidentally exposed to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-para-dioxin. Epidemiology. 1993;4:398–406. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199309000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colt JS, Severson RK, Lubin J, et al. Organochlorines and carpet dust and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Epidemiology. 2005;16:516–525. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000164811.25760.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colt JS, Davis S, Severson RK, et al. Residential insecticide use and risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:251–257. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeRoos AJ, Hartge P, Lubin JH, et al. Persistent organochlorine chemicals in plasma and risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11214–11226. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engel LS, Laden F, Andersen A, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyls in peripheral blood and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a report from three cohorts. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5545–5552. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fingerhut MA, Halperin WE, Marlow DA, et al. Cancer mortality in workers exposed to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:212–218. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101243240402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardell L, Eriksson M, Lindstrom G, et al. Case-control study on concentrations of organohalogen compounds and titers of antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus antigens in the etiology of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2001;42:619–629. doi: 10.3109/10428190109099322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kogevinas M, Becher H, Benn T, et al. Cancer mortality in workers exposed to phenoxy herbicides, chlorophenols, and dioxins. An expanded and updated international cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:1061–1075. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quintana PJE, Delfino RJ, Korrick S, et al. Adipose tissue levels of organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls and risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:854–861. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothman N, Cantor KP, Blair A, et al. A nested case-control study of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and serum organochlorine residues. Lancet. 1997;350:240–244. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas TL, Kang HK. Mortality and morbidity among Army Chemical Corps Vietnam veterans: a preliminary report. Am J Ind Med. 1990;18:665–673. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700180605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McConnachie PR, Zahalsky AC. Immune alterations in humans exposed to the termiticide technical chlordane. Arch Environ Health. 1992;47:295–301. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1992.9938365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tryphonas H. Immunotoxicity of polychlorinated biphenyls: present status and future considerations. Exp Clin Immunogenet. 1994;11:149–162. doi: 10.1159/000424206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tryphonas H, Bondy G, Hodgen M, et al. Effects of cis-nonachlor, trans-nonachlor, and chlordane on the immune system of Sprague-Dawley rats following a 28-day oral (gavage) treatment. Food Chem Toxicol. 2003;41:107–118. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Den Heuvel RL, Koppen G, Staessen JA, et al. Immunologic biomarkers in relation to exposure markers of PCBs and dioxins in Flemish adolescents (Belgium). Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:595–600. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weisglas-Kuperus N, Sas TC, Koopman-Esseboom C, et al. Immunologic effects of background prenatal and postnatal exposure to dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls in Dutch infants. Pediatr Res. 1995;38:404–410. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199509000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weisglas-Kuperas N, Patandin S, Berbers GAM, et al. Immunologic effects of background exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins in Dutch preschool children. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:1203–1207. doi: 10.1289/ehp.001081203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cerhan JR, Ansell SM, Fredericksen ZS, et al. Genetic variation in 1253 immune and inflammation genes and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2007;110:4455–4463. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-088682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lan Q, Zheng T, Rothman N, et al. Cytokine polymorphisms in the Th1/Th2 pathway and susceptibility to non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2006;107:4101–4108. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Purdue MP, Lan Q, Kricker A, et al. Polymorphisms in immune function genes and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: findings from the New South Wales non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Study. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:704–712. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothman N, Skibola CF, Wang S, et al. Genetic variation in TNF and IL10 and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the Interlymph Consortium. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:27–38. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70434-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skibola CF, Curry JD, Nieters A. Genetic susceptibility to lymphoma. Haematologica. 2007;92:960–969. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang SS, Cerhan JR, Hartge P, et al. Common genetic variants in proinflammatory and other immunoregulatory genes and risk for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9771–9780. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang SS, Cozen W, Cerhan JR, et al. Immune mechanisms in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: joint effects of the TNF G308A and IL10 T3575A polymorphisms with non-Hodgkin lymphoma risk factors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5042–5054. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chatterjee N, Hartge P, Cerhan JR, et al. Risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and family history of lymphatic, hematologic, and other cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1415–1421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, et al. A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 1994;84:1361–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colt JS, Lubin J, Camann D, et al. Comparison of pesticide levels in carpet dust and self-reported pest treatment practices in four U.S. sites. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2004;14:74–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lubin JH, Colt JS, Camann D, et al. Epidemiologic evaluation of measurement data in the presence of detection limits. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1691–1696. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans . IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Vol 69. Lyon, France: IARC; 1997. Polychlorinated dibenzo-para-dioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans. pp. 1–631. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van den Berg M, Birnbaum L, Bosveld AT, et al. Toxic equivalency factors (TEFs) for PCBs, PCDDs, PCDGs for humans and wildlife. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106:775–792. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindstrom G, Hooper K, Petreas M, Stephens R, Gilman A. Workshop on perinatal exposure to dioxin-like compounds, I: summary. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103(suppl 2):135–142. doi: 10.1289/ehp.103-1518837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagayama J, Tsuji H, Iida T, et al. Immunologic effects of perinatal exposure to dioxins, PCBs and organochlorine pesticides in Japanese infants. Chemosphere. 2007;67(suppl):S393–S398. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.05.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cozen W, Cerhan JR, Martinez-Maza O, et al. The effect of atopy, childhood crowding, and other immune-related factors on non-Hodgkin lymphoma risk. Cancer Cause Control. 2007;18:821–831. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skinnider BF, Kapp U, Mak TW. The role of interleukin 13 in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Leukemia Lymphoma. 2002;43:1203–1210. doi: 10.1080/10428190290026259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bugawan TL, Mirel DB, Valdes AM, Panelo A, Pozzilli P, Erlich HA. Association and interaction of the IL4R, IL4, and IL13 loci with type 1 diabetes among Filipinos. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1505–1514. doi: 10.1086/375655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner DM, Williams DM, Sankaran D, Lazarus M, Sinnott PJ, Hutchinson IV. An investigation of polymorphism in the interleukin-10 gene promotor. Eur J Immunogenetics. 1997;24:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2370.1997.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang X, Hei P, Deng L, Lin J. Interleukin-10 gene promotor polymorphisms and their protein production in peritoneal fluid in patients with endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13:135–140. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Breen EC, Boscardin WJ, Detels R, et al. Non-Hodgkins B cell lymphoma in persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is associated with increased serum levels of IL10, or the IL10 promotor -592 C/C genotype. Clin Immunol. 2003;109:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan CC, Whitcup SM, Solomon D, Nussenblatt RB. Interleukin-10 in the vitreous of patients with primary intraocular lymphoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120:671–673. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.